This series by American studies professor Ben Railton explores the connections between America’s past and present.

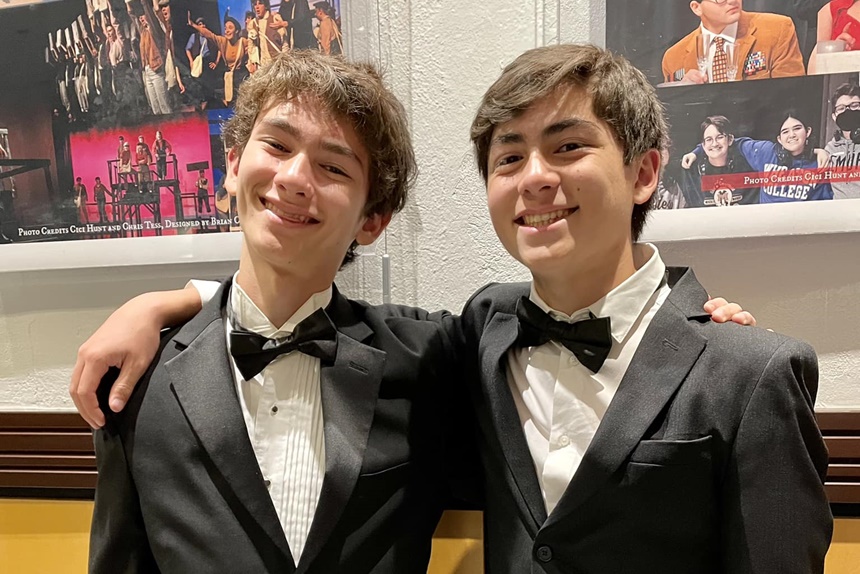

Two years ago, I wrote a Considering History column about my sons’ infuriating experience with racism at their sleepaway summer camp. Even though that subject represented a departure from the usual focus of this column, I sought to use that personal story to highlight some crucial historical and American (as well as profoundly human) lessons, to share what both the experience itself and especially their inspiring responses to it had taught me about topics like prejudice, allyship, and perspective.

The truth is, being a parent to these two amazing young men has taught me more than anything else in my life ever has or could. So I can think of no better way to celebrate Father’s Day in this space than with a column on two particularly meaningful such lessons from the last year. Through two impressive scholarly projects, my sons have helped me better understand how we engage with the past and how we fight for the future.

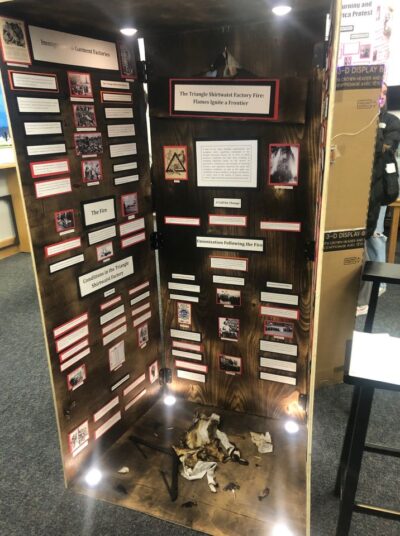

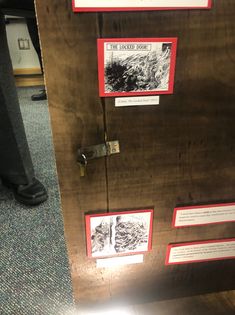

As a sophomore this past year, my younger son had the chance to take part in one of my favorite American educational initiatives, National History Day (NHD). This year’s NHD theme was “Frontiers in History: People, Places, Ideas,” and my son and his two partners chose for their subject the 1911 Triangle Shirtwaist Factory Fire. I’ve never seen students work with more dedication and passion than these three young men did over many intensive months, and as these pictures illustrate, the resulting project, “The Triangle Shirtwaist Factory Fire: Flames Ignite a Frontier,” was beyond exemplary. They earned the Best Exhibit Award at their high school and went on to win a very well-deserved Gold Medal in the NHD regional competition.

I learned a ton from the work ethic and commitment to excellence these teenagers displayed. I would also highlight three distinct aspects of the project that exemplify how to most thoughtfully and meaningfully engage with the past:

- The Bibliography: Every NHD project includes a required annotated bibliography; my son and his partners produced nothing less than 62 pages of such citations! I read every one of them (natch), and was struck both by their overall comprehensiveness and by their genuine engagement with the details and takeaways from each source. Every time we produce historical work, we’re doing so as part of a longstanding and evolving conversation, and this masterful bibliography reflects the best ways to learn and enter into that discussion.

Photo by Ben Railton - The Lock: History is about more than just sources and ideas, though; as I hope this column consistently exemplifies, it’s also and perhaps especially about stories of the worst and best of our past. Through one especially amazing detail on their project, the small lock (pictured) they attached to one side of the exhibit, my son and his partners captured one of our most horrific historical stories: that the Triangle Factory workers were locked in as the building burned, and that the factory owners fled the fire without unlocking the doors. Only by truly understanding such stories can we learn from our histories, and this small but perfect project detail can help us do s

- A Contemporary Connection: At every level of NHD competition, students are interviewed about their projects by the judges. Nerve-wracking as that process certainly is, it also offers the best students a chance to add even more layers to their impressive work. And at the regional competition, my son and his partners did so in a particularly thoughtful way: in response to a question about why these histories matter today, they brought up the July 2021 factory fire in Bangladesh, a contemporary story with far too many echoes of the worst of the Triangle fire (locked doors, victims jumping from upper floors, and more). I can’t imagine a more important lesson from engaging with history than this one: The past is never dead. It’s not even past.

While many of our contemporary moment’s worst crises echo historical tragedies, others represent terrifying new trends. No unfolding 21st century history is more unprecedented nor more horrific than the global climate crisis, and it is in response to that crucial issue that my older son has dedicated a great deal of his life and activism to date. He’s done so through political and social activism, including volunteering for Michelle Wu’s successful campaign for Boston mayor and for the grassroots organization Livable Streets; through personal and health choices like his vegetarianism and his leadership in the fight to bring healthier and more ethical food options to his high school; and through his evolving scholarly identity, including his internship this summer with a prestigious climate justice project.

As a junior this past year, my son was required as part of his Advanced Placement Language & Composition course to complete a Junior Issues Research Paper (JIRP). The assignment’s specific prompt was to analyze a contemporary issue through the lens of both individual and collective rights and freedoms, and my son chose to work on a topic that aligns closely with all of these other aspects of his life and activism: the global air pollution crisis, and how we can combat that crisis while balancing individual rights and freedoms with the collective right to breathe and live in a clean and healthy environment. His resulting, hugely impressive research paper and bibliography would not have been out of place in an advanced college classroom.

I learned a great deal from his work on that paper, including for example his ability to recognize and respect opposing arguments (such as the rights of individuals to pursue their own financial and personal goals and success) while making a compelling case both for his own arguments for the collective good and for how achieving that collective good will indeed benefit even those individuals. His bibliography was also (like his brother’s) an exemplification of that educational and scholarly genre, in this case in particular due to his inclusion of, thoughtful work with, and convincing responses to both specialized scientific studies and public-facing opinion pieces.

But when it comes to the fight for a better future, what I learned most from my son’s paper is an extension of what I learn from him and his brother every day. They are growing up in a world defined by potent and deepening crises, with climate change at the top of that all-too-competitive list. It would be easy and understandable for young people at least to ignore those horrors as best they can, if not overtly disconnect from the broader world as a result. Yet time and again, my sons choose to lean in, to learn from the worst of our past and present and rededicate themselves to fighting for the best of us, of our world, and of the future. I can no imagine no better Father’s Day gift than the inspiration I draw from those lessons and my sons!

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now