This series by American studies professor Ben Railton explores the connections between America’s past and present.

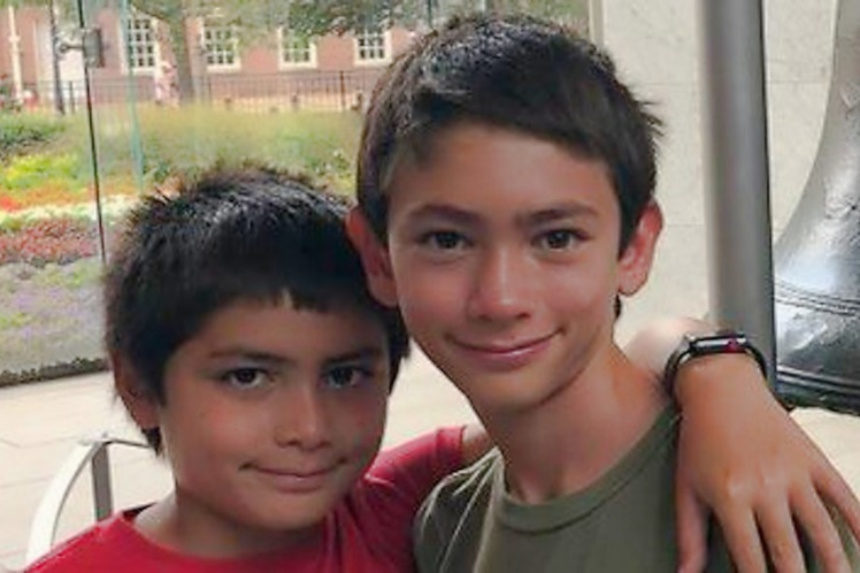

Over the last two weeks, my sons returned for the third time to one of their favorite places: a YMCA summer camp in New Hampshire. When they first went to sleepover camp there in 2018, I wasn’t sure how they would feel about it, and because there’s no communication from campers during camp, I remained uncertain that first time. But when I arrived to pick them up at the end of those two weeks, literally the first thing they said to me was “Can we sign up for next year?” They quickly and entirely fell in love with this little community, and it’s become a very important part of their summers (one they greatly missed last year and to which they were very excited to return).

Even though my older son has now aged out of regular camp and will have to be a counselor-in-training next year, the boys once again asked for pre-registration as soon as I picked them up. Yet despite that happy continued connection, this year’s camp experience was marred by a moment and fellow camper that reflected the worst of 21st century America. This teenage boy apparently expressed bigotry and prejudice toward any number of fellow campers, from anti-Black racism to homophobia, before he was finally sent home in the second week. And he targeted my sons as well, attacking their Chinese American heritage (on their mother’s side) with insults like “ching chong” and “yellow face.”

This was the first time the boys had been confronted with such racial slurs (or racial prejudice of any kind), and to say that I was and am enraged is to significantly understate the case. Bigotry is the thing I hate most in the world, and when you wed that to an attack on my sons…whew. But after making sure that they were and are okay (and are they ever, as I’ll detail below), the moment does offer me a chance to think through a few layers to such racism, from the most frustrating realities to the most inspiring responses.

One of those frustrating realities is how racism reduces our complex, multi-faceted identities to vessels for the crudest prejudices. Watching my sons begin to recognize and navigate their multi-racial identities and multi-cultural heritages, from their maternal Chinese American side to the Anglo-German-Jewish mélange that is my background, has been one of my life’s greatest joys. And here came this youthful bigot to reduce them to not just one layer of that very American mixture, but also and especially an ugly racist caricature. Racism and xenophobia alike all too often lead to actual violence and terrorism, but as expressions of rhetorical violence they are already destructive.

I keep emphasizing this particular racist’s age because it reminds us of another frustrating reality: how much such prejudice is inherited and taught. I’ve seen with my sons not only their gradual, thoughtful engagement with their own identities, but also their fundamental ability to accept and understand the identities of all those around them, including, for example, the transgender community that bigots present as such threats to young people. I very much believe such acceptance is the childhood default, and that it is only through negative influences — especially parents and family when we are young, but also political leaders and pundits who give in to prejudices like our current wave of anti-Asian hatred — that we develop instead prejudices and hatred toward others.

Those and many other frustrating realities illustrate racism’s endurance and its destructive power. But one of the central tenets of critical patriotism and critical optimism alike is that it’s in response to some of the worst of our histories that we can also celebrate some of the best of us, individually and collectively — and indeed that it is only in the face of the worst that the best is truly possible. In talking with my sons about this enraging experience, I’ve seen them model two particularly inspiring such elements.

The first is the importance of being an ally. It turns out that the teenage bigot was initially directing his racial slurs at a Chinese American fellow camper (and cabin mate) with whom the boys were playing tennis. In response, my younger son — who’s been standing up to bullies since he angrily told some much older kids to watch out for his brother in a McDonald’s PlayPlace more than a decade ago — said, “Hey, we’re Asian too!” This moment clearly identified the boys as “others” on whom the bigot could then turn his rhetorical violence as well. But I hope and believe that it was a meaningful moment for their fellow camper, that the boys’ vocal allyship made him feel less alone in the face of this bigotry, that it reflected the kind of solidarity and community that exemplifies the best of the camp, and that allows us to fight back against the worst of us far more successfully than anyone can do on their own.

The second inspiring element is being able to recognize prejudice for what it really is and whom it truly defines, and in talking with my older son he modeled precisely that vital understanding. I asked him if this first direct experience with racism had made him feel badly, at the time or since, and he replied, “No, I just thought, ‘Well, that guy’s a racist!’” Understanding that racism tells us far more about those expressing it than those targeted by it doesn’t in any absolute way elide its potential to cause harm, both rhetorical and actual. But it is nonetheless a thoughtful and significant perspective, one that can both help individuals navigate such enraging experiences and help us collectively diagnose where our social and cultural problems truly lie — a vital first step in challenging and transcending those flaws and failings, and moving toward the best form of shared community, whether at a summer camp or in a nation.

Featured image: courtesy Ben Railton

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now