Colorectal cancer, CRC for short, is the second-most common cause of cancer death in the United States, behind lung cancer. Approximately one in 25 people will develop CRC in their lifetimes. It’s very likely that you know a friend or family member who has suffered from it. Colorectal cancer is mostly a disease of old age, with a majority of cases occurring at age 65 and up. It often doesn’t cause any symptoms until an advanced stage, which could cause blood in the stool, abdominal pain, bloating, nausea/vomiting, weight loss, liver failure, or death.

The overall rate of colorectal cancer diagnosis and death has steadily decreased since the 1980s. But at the same time that older Americans have been less affected by CRC, Americans younger than 50 have suffered a sharp upward trend in colorectal cancer. This paradoxical trend in diagnosis and deaths led to the designation of “early-onset” colorectal cancer, EO-CRC, for those occurring prior to age 50. EO-CRC was in the news due to the deaths of celebrities such as Chadwick Boseman at age 43 and Quentin Oliver Lee at age 34.

Younger CRC patients appear to have more biologically aggressive cancers, with a higher rate of poorly-differentiated and advanced-stage disease. This has led to colorectal cancer overtaking brain cancer as the top cause of cancer death in men younger than 50. And while some CRCs are associated with obesity, alcohol, tobacco, and a sedentary lifestyle, the fact that physically fit actors can die of CRC means that not all CRC is caused by poor physical fitness.

We have a pretty good idea of why late-onset CRC is trending down: better cancer screening. Stool testing, CT colonography, sigmoidoscopy, and colonoscopy have all proven effective at preventing colorectal cancers and deaths. Colon polyps can often be detected and removed before they ever develop into invasive cancer. Advances in screening technology, and patient adherence to screening, have directly improved health outcomes in the U.S. and across the world. That’s a beautiful thing to see.

In contrast, the increase in early-onset CRC had been mysterious for years. Obesity, sedentary lifestyle, and alcohol use are known risk factors, but do not appear sufficient to explain the entire rise in disease, and tobacco exposure has actually decreased over time. Researchers have examined other environmental exposures ranging from antibiotics to synthetic dyes to high-fructose corn syrup, but have failed to find a smoking gun.

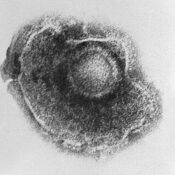

Other researchers have looked for answers in the gut microbiome, the thousands of microbial species living within each of our bodies. E. coli is the most common gut microbe in human beings, and there is immense diversity between E. coli genotypes. You can think of E. coli as the dogs of the microbe world, with E. coli genotypes as different as Chihuahuas and Great Danes. Most strains are friendly to humans, some hang around like a neighborhood stray, while others actively guard us from pathogenic intruders. Rarely, E. coli may behave badly, like a mad dog that can attack and kill. The O157:H7 strain of E. coli is infamous for causing foodborne illness, but it doesn’t seem to have any relation to cancer.

Other strains of E. coli, known as CoPEC or pks+ E. coli, have been found at a high prevalence in colorectal cancer patients. Pks+ E. coli secretes a genotoxin known as colibactin, and it’s entirely plausible that a genotoxin could cause cancer. So, there’s always been some suspicion that these bacteria could be an underlying cause of colorectal cancer. But that’s difficult to prove. After all, it’s also plausible that a cancerous gut allows for bad bacteria to thrive.

Is pks+ E. coli the mad dog of colon cancer, or just a stray picking scraps off the battlefield?

An April 2025 study led by Dr. Ludmil Alexandrov provides fresh evidence implicating pks+ E. coli as a cause of disease. Alexandrov’s team used a technology known as mutational signatures to detect patterns of chronic toxic exposures to colibactin. They found that early-onset cancers were much more likely to show colibactin genetic signatures, and that healthy people from countries with a high rate of early-onset colorectal cancer were more likely to carry colibactin signatures. Taken together, this is fairly strong evidence that pks+ E. coli is more than a scavenger, it’s an instigator of colorectal cancer.

Now that a culprit has been identified, the next step is to get rid of the offending bacterium. Unfortunately, that’s not as easy as shooing away a dog. Our gut is always full of microbes, and using antibiotics to get rid of one microbial strain runs the risk of leaving the gut vulnerable to being colonized by an even worse strain. Thus far, we don’t have any proven safe and effective method for preventing or treating pks+ colonization.

Based on first principles, you’re more likely to have a healthy gut microbiome if you practice good gut health. That means eating a diet high in plant-based fibers, whole foods, and fermented foods, and low in added sugars, ultraprocessed foods, and preservatives. Minimize your exposure to antibiotics and antimicrobials. Consider taking prebiotic/probiotic supplements, especially after a course of antibiotics. Nurture your good bacteria, and they could guard you like loyal hounds.

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now