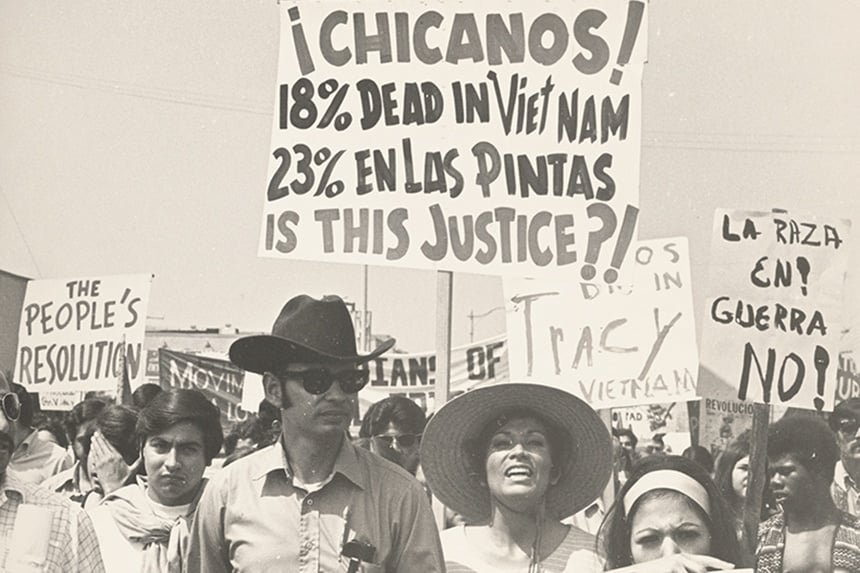

By the summer of 1970, Americans’ dissatisfaction with the Vietnam War was widespread. The expansion of the war into Cambodia in April and the Kent State shootings in May had only inflamed anti-war sentiment.

Though public dissent against the war continued to grow, the anti-war movement had stagnated as it struggled to overcome factional disputes. In contrast, the Chicano moratorium marches proved the “one major exception to the relative ebb in demonstrative antiwar” protests, notes historian Fred Halstead in his 1978 account of the anti-war movement, Out Now!. The August 29 Chicano Moratorium in Los Angeles, the largest and most important of the numerous Chicano moratorium protests, helped to reinvigorate the movement, drawing 20,000–30,000 people; it was, at the time, the largest antiwar demonstration by a single ethnic or racial group.

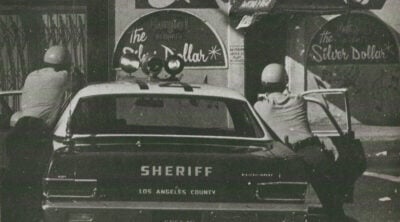

On that day, demonstrators had settled in for an afternoon of music and speeches. But what had started as a largely peaceful demonstration turned violent when Los Angeles Sheriff’s Department deputies overreacted to a disturbance and started beating participants, igniting a riot. As one participant told a Chicano newspaper, “One minute mariachi, next minute mayhem,” according to Lorena Oropeza’s book, Raza Si, Guerra No. The riot resulted in over 200 arrests, 60 injured, $1 million in property damage, and three dead.

Among the dead was journalist Ruben Salazar, who died when police fired tear gas projectiles into a café. His death outraged the community, serving as an inflection point for Mexican Americans and the Chicano movement. Salazar’s death resulted in far-reaching implications for both the Chicano movement and the larger Mexican American community, leading to significant changes in the fight for civil rights and political representation for Los Angeles Latinos. It also captured the continuing tensions afflicting relations between minority communities and law enforcement — tensions that are once again front-and-center.

Ruben Salazar Brings His Unrelenting Journalism to Los Angeles

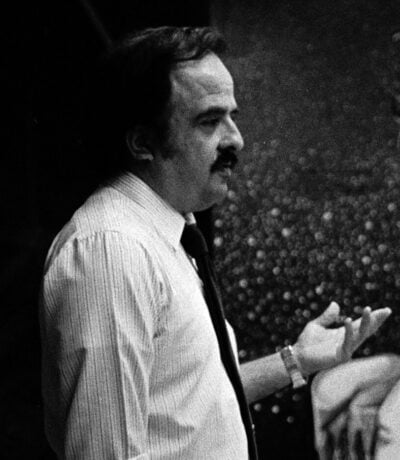

Ruben Salazar was the first Mexican American journalist employed as a reporter for the Los Angeles Times, the first to publish a regular column in a major English language newspaper, and the first to emerge as a relevant foreign correspondent. He had a reputation as a “muckraking social reform[er],” according to historian Mario T. Garcia. After covering the war in Vietnam and political and social unrest in the Dominican Republic and Mexico, Salazar returned to Los Angeles in 1969, turning his attention to the Chicano movement in both the Times and for television station KMEX as its news director.

Larger publications like the Los Angeles Times had rarely reported on Mexican American affairs, and even the Spanish language press failed to cover politics and current events in any meaningful way for Latinos. According to historian Edward J. Escobar, under Salazar’s leadership, KMEX’s coverage attempted to address the lack of attention, focusing on issues affecting the Mexican American community, notably its policing by Los Angeles law enforcement.

Salazar’s coverage of police brutality toward the Mexican Community — 1969 beatings of striking students of Roosevelt High School or the killing of two innocent Mexican nationals in 1970, for example — drew rebukes from the LAPD, who “warned [him] three times … to ‘tone down the coverage,’” according to Hunter S. Thompson. The LAPD had intelligence files on Salazar, including some from an informant at the Times. According to one of his aides, chief of police Ed Davis wanted to “tear ‘the hide right off [Salazar’s] back,’” Escobar wrote in a 1992 article for the Journal of American History.

Raúl Ruiz Exposes Police Wrongdoing

Though Salazar and Chicano activist and editor Raúl Ruiz were not particularly close, Ruiz was in many ways tied to Salazar, having shot the famous photograph showing Los Angeles county deputy sheriffs firing tear gas projectiles indiscriminately into the Silver Dollar Café on the day of the march, resulting in Salazar’s death. In the dichotomy between the two journalists, Ruiz represented the militant Chicano face of new journalism, while Salazar had worked his way into the establishment press, but had begun to channel the movement’s skepticism of Los Angeles authorities.

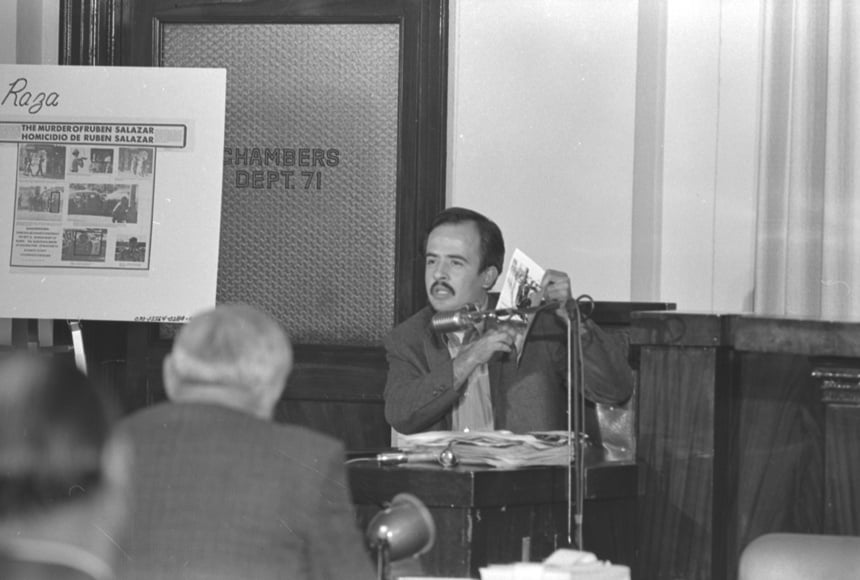

Ruiz served as co-editor and driving force of La Raza magazine, which spoke to the Mexican American community, focusing on advocacy and culture and protesting discrimination. It was from this perch that he reported on the events of the march, testified at the inquest into Salazar’s death, and advocated for the community by bringing an unrelenting focus on the actions of the L.A. Sheriff’s office.

The inquest following Salazar’s death was the most expensive in Los Angeles County history, lasting 16 days, introducing over 200 items into evidence, and producing over 2,000 pages of testimony. Despite clear animus by their superiors, nearly all the deputies denied even knowing of Salazar during their inquest testimony, a claim that stretched credibility, Ruiz argued.

Ruiz directly challenged the police narrative, initially with his photographs of the incident, first published in La Raza and then the Los Angeles Times; and second, in his testimony in the inquest.

The story coming from the police, observed Hunter S. Thompson, “was so crude and illogical — even after revisions — that not even the sheriff [Peter J. Pitchess] seemed surprised when it began to fall apart.” And this was even before the Chicano community asserted its opposition.

Beginning on September 10, local television broadcast the hearings in their entirety. Though the inquest lacked the ability to impose any real legal ruling, it was “imbued with the drama of a major event — set as it was in a context of police-minority relations and given the massive newspaper and television coverage normally reserved for major trials” noted Paul Houston of the Los Angeles Times.

The first days of the inquest featuring testimony largely by deputies, echoing the narrative that they were assailed with rocks and bottles, looting was rampant, and reports of armed gunmen came across the radios of those policing the event. The sheriff’s department played a 30-minute edited videotape that highlighted such instances without including any of the violence meted out by law enforcement, which observers argued sparked the widespread unrest.

In his unpublished manuscript on the inquest, “Silver Dollar Death: The Murder of Ruben Salazar,” Ruiz argues that “not one weapon was found or confiscated…with the exception of those which had been turned in by business owners,” nor was any gun ever “proven to have been used by any Chicano…on the 29th.” Ruiz added that ultimately, not a single deputy was wounded by a weapon of any kind. While numerous deputies testified that they heard reports of armed gunmen and even snipers, testimony provided little evidence to corroborate such accusations. “In reality these reports seemed to be total fabrications,” Ruiz wrote. Yet, law enforcement clearly availed their own weaponry on demonstrators and bystanders.

Chicano spectators at the inquest responded negatively. A blue-ribbon contingent assembled by the Congress of Mexican American Unity (CMAU), featuring Ruiz and La Raza co-editor Joe Razo, future Congressman Estaban Torres, and “celebrity” Chicano lawyer Oscar Acosta, among other notables, walked out twice on the first day, charging the testimony as impertinent. “You’re a disgrace to your profession,” Acosta yelled at the hearing officer Norman Pittluck. “Ruben Salazar was murdered,” shouted one audience member as they exited. “You are only attempting to make everyone in the country believe Chicanos are lawless and violent,” said Joe De Anda, a professor of Mexican American Studies at San Fernando Valley State College.

While there were more than a few critical moments in the inquest, perhaps the most important testimony came from Ruiz, which he later described as an “almost a surrealist experience.”

During the inquest, Ruiz’s photos documenting the police response to the march — over 60 introduced into the record — served as visual evidence of law enforcement’s brutality. In its September 16 issue, the Los Angeles Times described his testimony as “orderly and impassioned.”

Over two days of questioning, Pittluck consistently challenged Ruiz’s photographs as biased, asking the La Raza co-editor if he had taken any photos of protesters striking deputies, questioned why there were demonstrators carrying “Viva Che” posters, and requesting that Ruiz identify what Pittluck believed was a “wine bottle under a bench” in one photograph. The Times quoted Gloria Herrera, a director for the Congress of Mexican American Unity, asking pointedly, “What is he trying to say, that we’re a bunch of drunks?….What’s he trying to say there, that it’s all a dream — that you can’t believe pictures Chicanos take, but you can believe pictures deputies take?”

Ruiz acknowledged that some demonstrators responded violently, but that such actions were taken in self-defense. “The people most rightly did defend themselves. And if all they had to defend themselves with was a rock or a stone or a stick, then I think that was their right, because they were under direct attack.” He accused Pittluck of trying to undermine his integrity due to racial animus. “Not one question of this sort was placed to any other witness,” he said.

According to writer Carribean Fragoza, Ruiz’s two days of testimony mattered because it showed “Mexican Americans something they’d never seen before. In the courtroom and on their television sets, they saw an educated, politicized Chicano speaking truth to power.”

When the inquest concluded, jurors ruled 4-3 that Salazar had died “at the hands of another,” a catch-all legal conclusion that obscured more than it revealed. “I don’t say it was murder,” reflected one juror. “But I think the action of the officers was ridiculous, and I think a 10-year-old boy could have done better.” “[T]he entire jury felt there was definite negligence on the part of the sheriff’s department and that the deputies did not use discretion or prudence in their acts that day,” juror Betty J. Clements told the Times. The jury’s foreman, who voted in the minority, conceded that all seven believed law enforcement to be at fault, the Times reported on October 8. The ruling had no legal authority, and the Los Angeles district attorney refused to pursue charges against the deputies.

While a clear tragedy for Salazar’s family and the Chicano community, Hunter S. Thompson noted that the incident carried even deeper implications. Thompson was friends with Oscar Acosta, who alleged that Salazar’s death was no accident. “[T]he most ominous aspect of Oscar’s story was his charge the police had deliberately gone out in the streets and killed a reporter who’d been giving them trouble,” Thompson wrote. “When the cops declare open season on journalists, when they feel free to declare any scene of ‘unlawful protest’ a free fire zone, that will be a very ugly day — and not just for journalists.”

Four decades later, in 2011, journalist and novelist Hector Tobar spoke with Raúl Ruiz in a Boyle Heights restaurant to discuss the unrest that unfolded at the event and the tragic death of Salazar that came to define it. Ruiz brought with him a “3-inch-thick manuscript” in which Ruiz summarized all the “publicly available evidence” regarding Salazar’s death, the majority of which was drawn from the inquest into the journalist’s killing that followed, Tobar reported in the February 23, 2011, Times.

At the time, in the face of forty years of skepticism over the inquest’s findings, Los Angeles authorities were discussing the possibility of releasing all its files regarding the Salazar incident. Salazar’s death, Ruiz’s involvement, and the subsequent inquest serve as a window into current debates regarding the policing of minority communities and the role of journalists.

Over the ensuing decades, argues historian Edward J. Escobar, Salazar’s death and other conflicts with Los Angeles law enforcement bred “a consciousness that included a greater sense of ethnic solidarity…and a greater determination to act politically, and perhaps even violently.” Mexican Americans gained greater political representation, earning seats on the city council and in the state and federal government. CMAU director Estaban Torres, among others, won a seat in Congress.

A 2011 independent investigation of the shooting, but not the inquest, concluded that sheriff’s deputies made numerous mistakes on August 29, 1970, including the use of tear gas, which even by the standards of 1970s policing was “contrary to … [the] department training.” Rather than investigate the incident thoroughly, the sheriff’s department “circled the wagons around its deputies, offered few explanations and no apologies,” a “posture [that] fueled the skeptics.” In the end, it was a “hashed up operation in a sea of chaos … [which] resulted in the tragic death of Mr. Salazar rather than a deftly designed assassination.”

Salazar’s family won a $700,000 settlement from Los Angeles County in 1973, and he soon became an icon in the Mexican American community as “parks, schools, and scholarships were named in his honor.” In 2008, the United States Postal Service issued a stamp commemorating him.

Ruben Salazar’s Legacy Lives On (Uploaded to Vimeo by Robert Lopez)

Yet, Salazar’s death at the hands of law enforcement serves as a reminder of the growing tensions today between law enforcement and journalists. Over four days in Los Angeles this past June, “nearly a dozen journalists … were struck by projectiles fired by law enforcement authorities,” notes journalist John D’Anna, who also draws comparisons to the Salazar shooting. That the conflict erupted over ICE raids targeting the city’s Latino community underscores the disturbing parallels between 1970 and today.

As for Ruiz, who died in 2019, his skepticism never wavered in his belief that Salazar’s death was due to more than the incompetence of sheriff’s deputies, telling Tobar in 2011, “To this day, I have not accepted the fact that Ruben was killed by a tear gas projectile.” In the end, whether incompetence or conspiracy, the end result remained tragically much the same.

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

I’ve been trying out this straightforward online project, and it’s been averaging around $95 a day for me — r about $670 a week. It only takes a couple of hours on my laptop, nothing complicated. I put the steps I use

Just Tab On My Name