Before most people had a computer at home, they encountered them in the office, at schools and universities, or in the military or government.

Computers were for work, at work.

So, selling people on the extravagant idea of a computer for themselves was challenging.

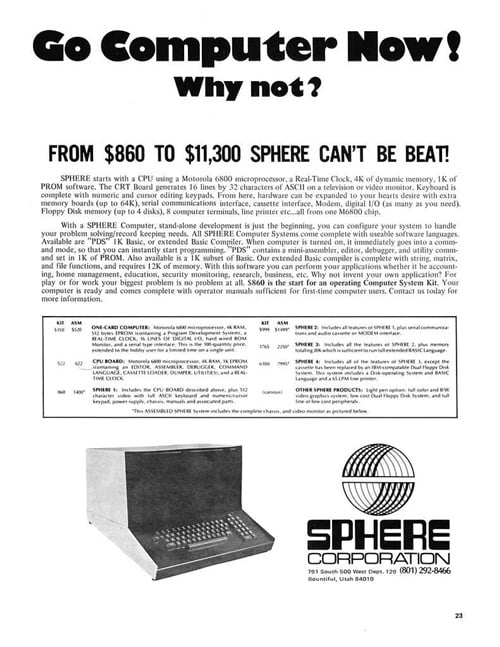

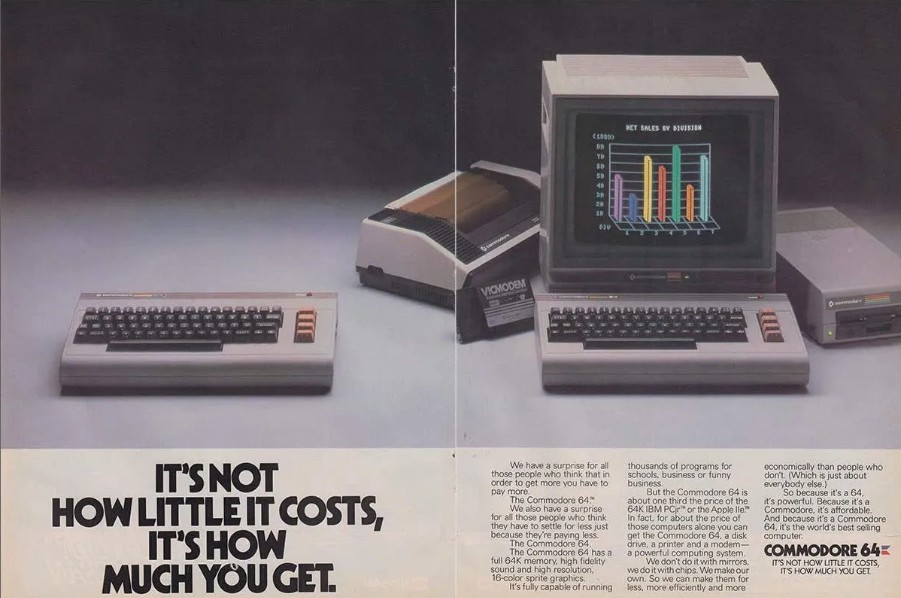

First of all, they were expensive; in the early 1980s, a computer could easily cost $4,000 or more in today’s money for a complete system. By the early 1990s, that price had gone down enough to make it more manageable, but it was still not cheap.

Second, a computer’s memory – where it holds data and instructions — was minuscule compared to today. The Commodore 64, which was released in 1982, had 64 kilobytes of memory; today, an average laptop has around 8 GB of memory — more than 16,000 times as much. Storing more than a few files was not that realistic, for most potential users. If you wanted more memory, you would pay dearly for it; a hard drive that would have cost $1,000 some 30 years ago would cost a small fraction of that price today.

Third, those early “desktop” computers were large, clunky, and hard to operate without training.

But the main reason they were such a hard sell was that people really didn’t know why they would possibly need a computer in their home. Their utility for the needs of everyday life — as weird as this is for many of us to remember — was hard to understand. To put it another way, if you don’t need an expensive tool, you won’t buy it.

Between the price, size, and perceived lack of usefulness, the rationale for buying a home computer system in the 1980s and early 1990s was lacking. This was especially true before the arrival of the civilian internet in the mid-1990s.

Computer manufacturers had to figure out how to sell these machines to people who weren’t already “power users” (business executives who could afford to equip themselves with a home office). They had their work cut out for them.

Selling the “Personal”

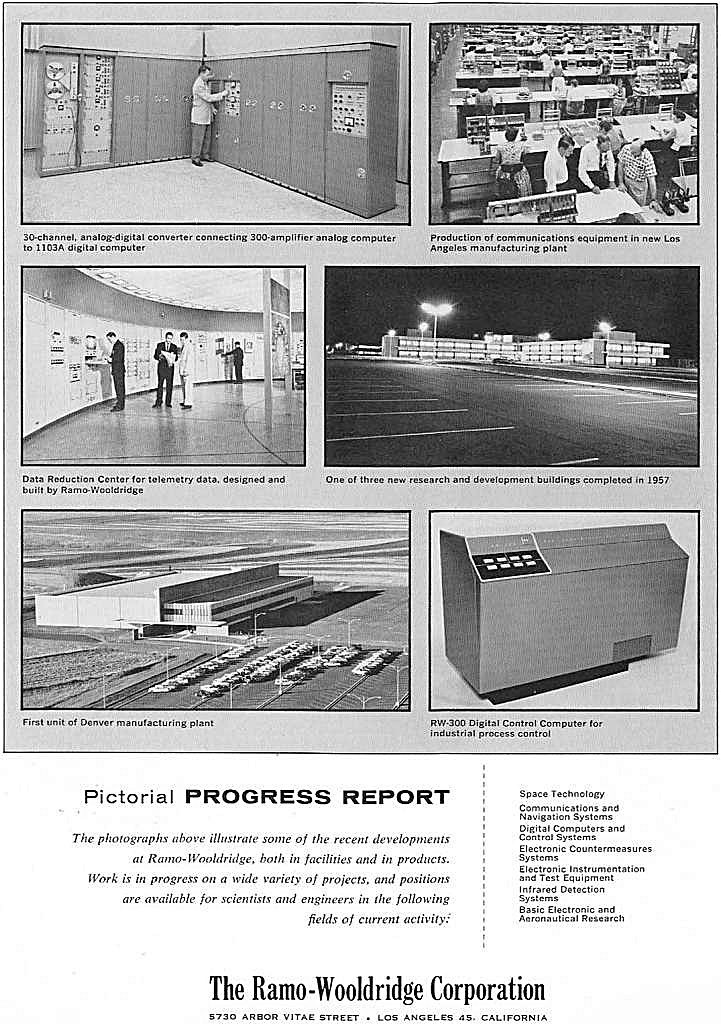

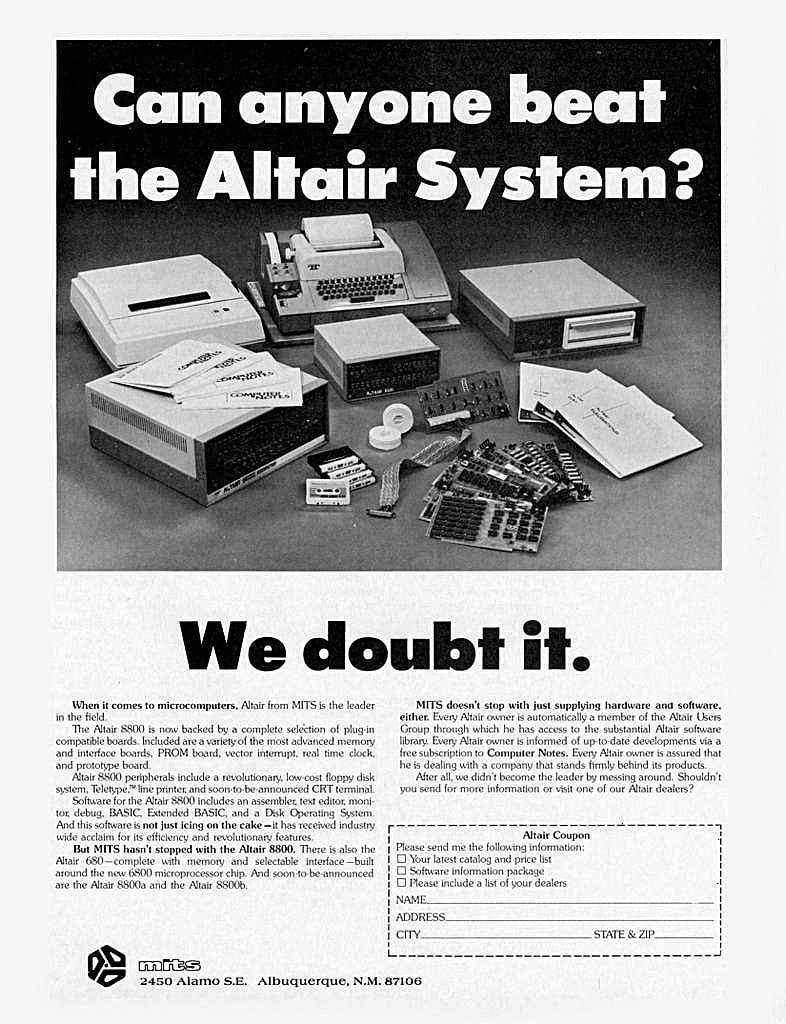

In the early days of the personal computer, manufacturers targeted power users, gamers, and geek-hobbyists (these users were already basically amateur electricians who enjoyed building their own computers with soldering irons and spare parts).

Some ads, as for the Commodore 64 — my dad’s (and thus our family’s) first home PC, incidentally — promoted its low-ish price point and ease of use.

Generally, ads for computers were more text-heavy than we’re used to today, and would have appeared more in magazines than on TV. Of course, some, such as Apple’s “1984” spot, remain famous because they appeared on TV (in this case, during the Super Bowl). The Apple ad was important because it made computers seem anti-authoritarian, even a little rebellious and, of all things, stylish. That wasn’t an easy sell.

Apple’s “1984” ad (Uploaded to YouTube by Mac History)

Other ad campaigns, such as IBM’s (in a belated attempt to challenge Apple), were a little random, in one case featuring Charlie Chaplin. Despite IBM’s market lead, Apple’s efforts are more remembered today, perhaps because of the underdog mythos cultivated by Steve Jobs and, again, that sense that a computer could be…fun.

An IBM ad from 1983 featuring an actor dressed as Charlie Chaplin (Uploaded to YouTube by Betamax Archive)

Other companies’ ads used every possible appeal, from celebrity endorsements (like the cast of M*A*S*H) to more logical appeals, including the idea that a computer would help a family save money by tracking its monthly food budget. By the 1990s, ads pushed the decreasing cost of getting of a PC and their comparative “portability” (and by portable, these were more “luggable” — you could lug a 12-pound computer onto a plane). Also, users could play increasingly sophisticated games on them; popular ones included Prince of Persia, Microsoft Flight Simulator, and later on, Myst, Age of Empires, and Civilization.

Early personal computer commercials might use celebrity endorsements to sell their products (Uploaded to YouTube by The Root User)

Some machines highlighted their emergent but practical applications (ranging from calculators to spreadsheets to calendars) and hence their capacity to enable office work from home, still a quasi-alien concept for most people at the time.

Hobbyists — those who already tinkered with computers, and many who could program or build their own — were an important part of the computer ad market, too, even though selling to them involved more nuance and detail (and perhaps more finesse) than, say, a new user. A hobbyist would want to know things like where and how a cooling fan was installed, how much electricity a motherboard would use, if there was room for connections to peripherals such as joysticks, if new memory cards could be installed, etc.

But the key objective of these early ads was to get the person who wasn’t a hobbyist or a power user to buy a computer. The idea that selling new kinds of technology involves appealing first to early adopters and then the rest of us is not a new one. It’s based on an old theory of tech adoption called “diffusions of innovation,” popularized by Everett Rogers.

To put it another way: At first, buying a computer for oneself was rare, but eventually, consumers were persuaded that doing so could make them smarter, more efficient, or even cool.

Eventually, ads about the early internet emphasized how it could enhance your computer’s utility. One of the first such commercials, by CompuServe, emphasized how you could get the latest news, shop, and connect to databases. Other ads hyped the potential connections to the wider world that the web could bring, to both families and individuals, with an emphasis on relationships with other people through message boards, listservs, and electronic mail.

A CompuServe ad from 1989 (Uploaded to YouTube by Geo Marketing Partner)

Eventually, computer advertising became more mainstream with ads about the early internet. These commercials hyped the potential connections to the wider world that the web — and your new computer — could bring, with an emphasis on relationships with other people.

This Kids Guide to the Internet showed families how these early computers could help their children succeed (Uploaded to YouTube by Green Tea Break)

Smaller companies such as Gateway seemed to grasp this way of selling computers (PCs plus the internet) more intuitively than most, by packaging their computers with the tools to connect to the internet more easily, and making them easy to set up and maintain. The concept of having a world wide web to “surf” was cheesy but arguably effective, especially for anxious parents eager to set up their kids for success. For those with kids, the concern was to give them an edge in school, since “computer skills” would be required for future jobs; in this sense, many ads were, in fact, aimed less at kids and much more at their parents.

Even The Saturday Evening Post got in on the action with a helpful story from their April 1, 1981, issue on how families were using computers in their everyday lives.

The Legacy of Computer Ads Today

In many ways, buying a computer has become a mundane experience, like picking out a new microwave instead of having it be a bespoke experience.

And today’s ads for computers reflect this: They are more like ads for any other product. This is perhaps best illustrated in how telecom companies advertise smartphones (which are basically computers). Instead of selling their features, per se, like the first generation of Apple’s iPhones and their rivals, in recent years they’ve been more tied to data plans and savings. That is, they’ve become a commodity.

While the individual act of buying a computer today is more tied to getting a good deal than changing your life, they have changed our lives. Those early ads tried their best to convince you that you needed a computer, but the fact is that today most people no longer need convincing: They can’t imagine living without one.

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

Very early adopter of computers here, saw my first one in 1976, bought my first one in 1980. Fast forward to today – after retiring from a career that was all about computers, I’m still an enthusiast. However, I consider smartphones to be completely stupid, expensive, and useless.

A fascinating article with these print and later video ads (all state-of-the-art for their times) bringing the computer into the relatively modern sense we know it to be now, by the turn of the century. Of course it’s evolved since then, and will continue to, but the toughest part was really over within a few years of the internet becoming essential part of modern life to clinch things.

The Saturday Evening Post’s 1981 feature was ahead of its time for the time. It was also about the first magazine to have an internet website presence in addition to the print magazine, going back to the late ’90s. The early version evolved to the perfect interactive one we have today.

The internet has helped the Post in recent decades the way television ended the large-format, general interest magazines several decades ago, mainly from sucking away their life blood: the advertisements. The weekly/biweekly print magazines were not economically sustainable, at all, and unfortunately HAD to be shut down in that form.

LIFE and Look magazines would have been shut down even sooner were it not for cigarette ads being banned from TV at the end of 1970. That and the hard liquor ads were hardly enough to survive on with high circulations, skyrocketing paper and postal costs looming. Reinvention and a fresh start would be needed and done, to get around all that.

Because of the internet, the Post is able to offer as much content in a single week as it would if it were still in the weekly general-interest physical magazine frequency. Its simply transferred to the screen. The bimonthly physical magazine is still ground zero for what makes the Post the Post, but the online counterpart helps both complement each other as needed, with high fives and well-deserved backslaps for doing such a wonderful job.

Being a retired Information Systems Manager and Programmer/Analyst on IBM Midrange Systems (AS/400, Systems/34-36-38), I was not onboard with PCs when they first came out and I was quite apprehensive when they were connected to the internet. While I think humankind would have been best served had cell phones, PCs, and the internet had never been created or evolved, I know nowadays from a practical standpoint life as conducted (Mostly) would not happen. As a biker, I can’t register for any respectable motorcycle rally without internet access. I do however use, and will continue doing so a desktop PC simply for the fact I know by using them your transactions are more secure in the wild world of web.

My parents got their first computer sometime in the early eighties. I told them they had been taken. I’d tried computers in High School and college and didn’t see the appeal and did not trust that “internet” thingie. I didn’t get online until the late nineties when I realized I had no choice.