Since July, children in every state have been stepping back into the classroom along with their teachers. In total, approximately 55 million American kids ages 5 to 18 will attend school between now and May or June 2026, mostly in public schools. About 15 percent of all students — about 7.6 million children, ages 3 to 21 — receive special education services to support their learning. Some of these supports include classroom and testing accommodations, support from an aide, assistive technology, interpreters, or speech or occupational therapy. Each year, parents and teachers and administrators work to evaluate student needs and determine how to best support children with learning differences. But for more than a century, educators, parents, and activists have been fighting to provide students with these services.

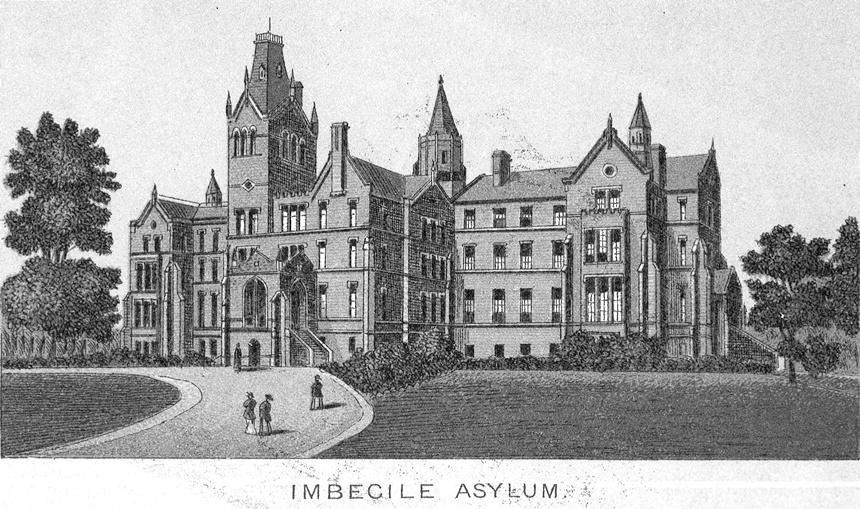

Throughout the 1800s and early 1900s, children with special learning needs were placed into separate schools away from general education students or even institutionalized. According to Philip L. Safford of Kent State University, “Many of the inmates of America’s almshouses [in the mid-1800s] were children with physical or cognitive impairments.” Many states had laws excluding students who were deaf, blind, emotionally disturbed, or had an intellectual disability. Some of the earliest programs were schools for students who were deaf or blind, such as the American School for the Deaf, founded in 1817, and the New England Asylum for the Blind, founded in 1829.

It wasn’t until the 20th century that educators began systematically identifying students who had other learning disabilities. In the early 1900s, Elizabeth Farrell proposed an inclusive model of what is now known as special education. Her idea of “ungraded” classes was integrated into the New York City public schools, creating classrooms that grouped children by age and ability. Farrell argued that “The special school with its ‘separateness’ emphasized in its construction, in its administration, differentiates, sets aside, classifies, and of necessity stigmatizes the pupils whom it receives. How could it be otherwise?” She was one of the first educators in the United States to attempt to evaluate students to understand what challenges they faced in their efforts to learn.

Farrell’s hope was that in ungraded classrooms, students would receive more specialized attention and be able to learn and excel in their own ways. “The function of the school is to provide an environment in which the abilities and capacities of each individual may unfold and develop in a manner that will secure his maximum social efficiency.”

The New York City public schools’ ungraded classes were one of the few early efforts to provide inclusive special education. Across the nation, children with special educational needs were largely excluded from public school entirely. In the 1930s and 1940s, parents began forming groups in their communities. The Cuyahoga County Board of Developmental Disabilities was formed in Ohio in 1933, specifically to support families whose children were not allowed in public schools because of their disabilities. The Arc of Washington State was established in 1936 to meet family needs in that state, and in New York, the AHRC New York City was created in 1948 when Ann Greenberg placed an ad in the New York Post looking for other parents of disabled children who wanted to create a nursery together. Similar efforts spread across the nation through the 1950s, with parents working together to address the challenges they faced in finding support for their children.

In the postwar years, American families pushed back against medical professionals who told them their children should be institutionalized, or that there was nothing that could be done to help them. They began to work together, advocating for their children and pushing for change. In 1950, Pulitzer- and Nobel Prize-winning author Pearl Buck wrote a memoir, The Child Who Never Grew, about her daughter, who was mentally disabled. In 1953, Dale Evans Rogers, the wife of actor Roy Rogers, published Angel Unaware, about their daughter Robin who was born with Down Syndrome in 1950 and died at the age of two. More than ever before, Americans were talking about children with mental and physical disabilities — and the lack of resources for them.

When John F. Kennedy became president in 1961, he created the President’s Panel on Mental Retardation. The task force provided recommendations about all aspects of life for those with intellectual disabilities. It was a matter of personal significance to him: His younger sister Rosemary was born with intellectual disabilities, and in 1946, his family had created a foundation focused on intellectual disability.

At the same time, 14-year-old Judy Heumann had become one of the first wheelchair users able to attend public high school in New York City. As she writes in her memoir, Being Heumann, her mother and a group of other mothers had fought to get some schools wheelchair accessible. Heumann lost the use of her legs from polio when she was 18 months old, a common outcome before the polio vaccine was developed. Until age 9, Heumann was denied entrance to her local public schools because being in a wheelchair made her a “fire hazard,” according to the principal.

As a student at Long Island University, Heumann studied to become a teacher, but in 1970, the New York City Board of Education denied her teaching licensure because she could not walk. The board claimed that her lack of mobility in case of a fire was a problem. Heumann sued in federal court, claiming a violation of her civil rights. The judge who heard her case was Constance Baker Motley, the first Black woman to become a federal judge and a member of the legal team for Brown v. Board of Education 20 years earlier. The school district agreed to give Heumann a third medical exam, part of the licensure process, and granted her a teaching license. She taught for a year, then helped found Disabled in Action, a disability advocacy group.

By the mid-1970s, Heumann was a legislative assistant for Senator Harrison Williams, who chaired the Senate Committee on Labor and Public Welfare. Senator Williams was one of several members of Congress who dedicated attention to disability issues, along with Bob Dole, John Brademas, Alan Cranston, and Hubert Humphrey. As a member of his staff, Heumann went on to support what became the 1975 Education for All Handicapped Children Act. This law established the principle of educating children in the least restrictive environment, putting children with special needs into general education classrooms to the best of their ability. It was a law that would fight the limitations Heumann herself had encountered as a child.

The Education for All Handicapped Children Act was a milestone achievement. Under the new law, public school districts had to evaluate children’s learning needs and create Individual Education Programs (IEPs) to support each child with identified special needs. Putting children in the least restrictive environment possible created an inclusive educational environment for more children than ever before. During the 2022-2023 school year, for instance, two thirds of children receiving special education support spent at least 80 percent of their day in general education classrooms.

In 1990, the goals of the Education for All Handicapped Children Act were expanded and reinforced under a new name: the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA). Under IDEA, the United States government promised that the federal government would provide 40 percent of the funds needed for each student receiving special education. Despite IDEA’s promise of federal funding, there are gaps. As of 2025, the federal government provides only about 12 percent of those funds.

The progress of the last half-century is undeniable, but the legal and practical battles that followed reveal how fragile that process remains. In 1982, for instance, Amy Rowley’s parents lost a Supreme Court case that fought for her access to a deaf interpreter under the Education for All Handicapped Children Act. The Supreme Court ruling expressed limitations to the government’s requirements to support students under that law. Funding, costs, and staffing issues continue to make it challenging for many families to receive all the services their children need.

From Elizabeth Farrell’s early experiments to IDEA, families and educators have transformed education for children with disabilities. Yet legal limitations, funding gaps, and staffing shortages show us the law’s promise is still challenging to fulfill. The field of special education has advanced significantly, but just as every generation has shaped new visions of what is possible, so too will the future demand renewed commitment to inclusive educational opportunity.

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

I believe this story shows the development of services for students with disabilities. I don’t see how it is one-sided. The story presents the facts regarding the history and the lack of educational opportunities for children with disabilities, especially those with severe disabilities, throughout the centuries. Have you ever seen the inside of an institution full of children with disabilities? Probably not. Most are closed now – watch the report Geraldo Rivera did (it’s on YouTube) about Willowbrook in the 1970s. That started the deinstitutionalization of children with severe disabilities. Now, most children are in their neighborhood school or receive services from a center-based program in their home district. Many schools are successfully supporting students with extensive needs in the general education classroom.

Are you a family member who has a child with a disability? I have been a special education teacher, administrator, professor, and parent of a child with a disability. It is not easy for parents of children with disabilities to understand their rights and ensure their child is receiving the most appropriate education, but they try their best. School Districts do their best to cover all the needed services to students with disabilities, but the Congress’s lack of funding does stretch every dollar from the state/district to do the best they can for children with disabilities. I’m going to send this article to a few individuals who clearly don’t understand the history of special education services and how far we have come. By the way, Special Education is NOT a PLACE, it is SUPPORTS AND SERVICES delivered to students with special needs.

Michael, I agree with you. This story was much slanted.

A fairly one-sided story. That makes it much more emotional. It would be nice if the reasoning from both sides were presented instead of appearing to vilify one ‘side’ of the story that had many sides. There was a huge difference in how people lived and what the limitations were 100 years ago.

Ms. Thelma Rodriguez

148 East 28th Street

Brooklyn NY 11226

Mercy Home For Children

AHRC 355 Kings Highway

1299 Ocean Avenue

1601 80th Street

24 Paerdegat 13th Street