In October 1953, the Washington, D.C., Evening Star newspaper’s Sunday magazine This Week ran an advertisement inviting readers to send in for a print of Over the River to Grandmother’s House by the artist Grandma Moses. The headline, “How to get your copy of this Grandma Moses Christmas Original,” invited readers to mail $1 (about $12 today) to claim a copy, allowing people across the country to enjoy the work. The image, across a two-page spread, showed a hilly, snow-covered landscape dotted with farms and farmhouses, where tiny people walked or rode in a horse-drawn sleigh, a scene that felt like the holidays Americans remembered or imagined. “The Christmas-season picture,” the advertisement proclaimed, “is one of her earliest and best.”

In the 1950s, Anna Maria Robertson Moses’s work was everywhere. Americans had embraced the story and art of the former farmwife who began painting in earnest only at age 78, captivated by scenes that felt familiar and comforting. In November 1940, the year she turned 80, Gimbels Department Store in New York City made Moses a centerpiece of their Thanksgiving celebration, referring to her as both a “great American artist” and “a great American housewife,” the kind that made home the place to be at the holidays. By 1947, the connection between Grandma Moses’s artwork and holiday celebrations went a step further when Hallmark gained the license to create greeting cards from the images. In the decade-and-a-half after World War II, Grandma Moses’s work was not only on prints and greeting cards, but had also been reproduced as fabrics, plates, and shortening cans and displayed across the country and in Europe, embedding the images into everyday and holiday life.

Grandma Moses saw connections between the past and memory in her painting. In 1953, she told a Time magazine reporter, “I like to paint oldtimy [sic] things — something real pretty. Most of them are daydreams, as it were.” This echoed her autobiography published a year earlier, where she wrote, “Memory is history recorded in our brain, memory is a painter, it paints pictures of the past and of the day.” Moses’s artistic themes, and perhaps her age and her identity as a simple farmwife, drew millions of people to her work. In the decades around World War II, it seemed that Americans, too, were interested in remembering the world she depicted in her art.

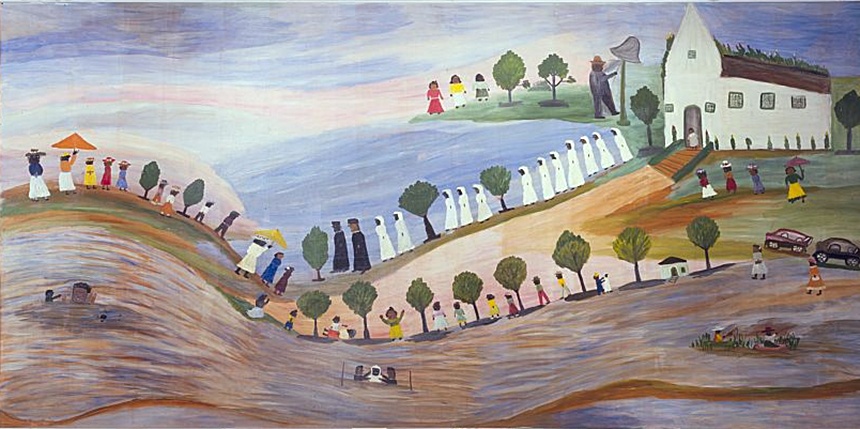

Halfway across the country, Americans were also being drawn to another self-taught, grandmotherly artist: Clementine Hunter. Like Moses, Hunter began painting later in life, translating memory and experience into vivid images of her world. In 1939, Hunter began painting scenes from the cotton fields around Louisiana’s Cane River. She depicted images of life at Hidden Hill Plantation, where she had been born in the 1880s, and Melrose Plantation, where she lived and worked as an adult. “I tell my stories by marking pictures. The people who lived around here and made the history of this land are remembered in my paintings.…My paintings tell how we worked, played and prayed,” she once explained. Hunter’s art focused on people and their activities, such as doing laundry, going to church, or picking cotton. Religious scenes from African American life and the Bible were not uncommon.

Though the two artists began painting around the same time in the 1930s, Hunter was more than 20 years younger and lived 1,500 miles away. Both artists, however, offered Americans their own visions of the nation’s past. Moses’s name and work appeared regularly in newspapers nationwide, and she received an award from President Eisenhower. Hunter’s work traveled more slowly, with exhibitions in St. Louis, New Orleans, and other places in Louisiana. When Northwestern State College in Natchitoches exhibited her work in 1955, segregation laws kept Hunter from attending during viewing hours, according to Anne Hudson Jones’s 1987 article in Woman’s Art Journal. By the 1970s, Hunter’s work was reaching new audiences, though never at the scale of Moses’s.

In a 1985 interview, Hunter said, “I used to pick up little pieces of board and all kinds of little pieces of paper. Painted on everything. I didn’t know if I was doing right or wrong, but I was painting. And I gave it all away. I liked what I was painting.”

Moses and Hunter were both American artists who gained respect and admiration for their images of American life and memory, but timing, audience, and other factors shaped how widely their work circulated. On December 18, 1961, Grandma Moses died at the age of 101, with President Kennedy remarking that “her work and her life helped our nation renew its pioneer heritage and recall its roots in the countryside and on the frontier.” In 1988, Clementine Hunter died, having also reached the age of 101. By 1985, her work was being sold for thousands of dollars.

Today, museums exhibit both artists’ works: the Smithsonian American Art Museum recently opened a Grandma Moses exhibit, while the National Museum of African American History and Culture and the African American Museum in Dallas feature Hunter’s paintings. The American Folk Art Museum in New York City includes art by both artists in its collection: one painting by Grandma Moses and 23 by Clementine Hunter. Today, it’s still possible to purchase holiday cards featuring Grandma Moses’s work, or Hunter’s work as Christmas ornaments.

Both Moses’s and Hunter’s depictions show how our ability to feel, recall, and connect with the past can depend on who encounters the work, and when. The two women lived and worked at the same time, but their lives reflect the vast range of the American experience. They remind us that memories continue to resonate, long after the artists first put brush to canvas.

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

What a wonderful feature on both of these classic American artists. Each woman had her own take and style on subjects that crossed similar paths. I appreciate the links toward the bottom on how each woman’s art is honored and respected in the present day. The fact each one lived to 101 years old is yet another remarkable commonality they share.