In late spring 1893, the Columbian Exposition brought the world to Fannie Barrier Williams’s hometown of Chicago. One of its early events was the week-long World’s Congress of Representative Women, gathering women from around the world. On the fourth night of the congress, Williams took the podium, becoming the first Black woman to address the attendees. With her speech, “The Intellectual Progress of the Colored Women of the United States Since the Emancipation Proclamation,” Williams set out to show the world what Black American women had achieved and the challenges they still faced. “Less is known of our women than of any other class of Americans,” she explained. That night, she took her audience beyond the Exposition’s gleaming visions of progress to show them the nation Black women inhabited.

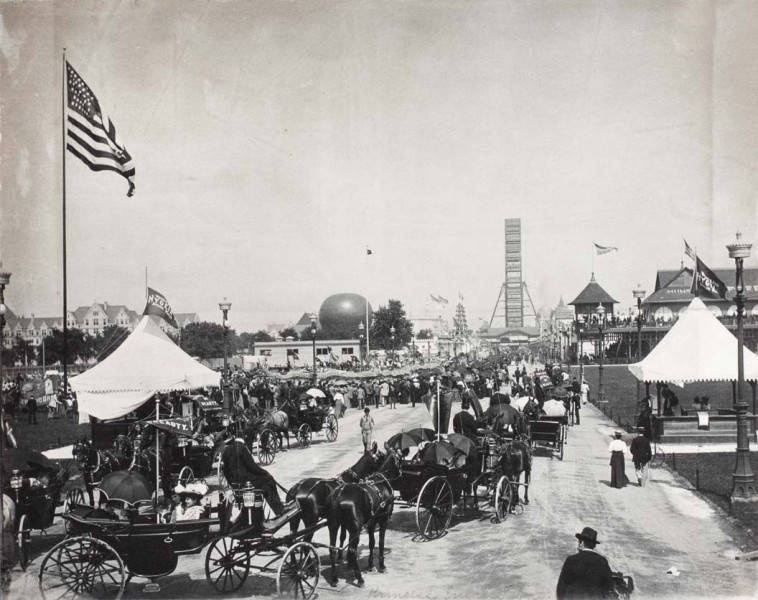

For more than two weeks, fairgoers strolled through the famed “White City,” a temporary set of buildings designed to present a particular version of the United States. The country was in the midst of an industrial age, marked by big business and rapid technological change, and millions continued to migrate to the United States in search of opportunity. The world was paying attention to America, and for six months in Chicago, Americans like Fannie Barrier Williams could see the world as never before. On the one-mile-long Midway Plaisance, visitors encountered carefully curated booths and global attractions, from the Japanese Bazaar and a German village to a replica of the “Streets of Cairo.”

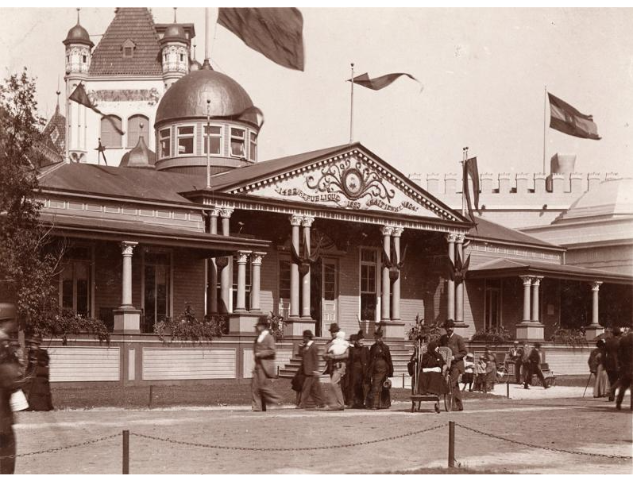

Farther away from the Midway Plaisance, fairgoers could learn about 18 different countries and colonies by visiting the Foreign Buildings section of the exposition, which functioned more like museums. Among those buildings, only one represented an independent Black-led government: Haiti, its pavilion nestled between colonial East India and New South Wales. There, visitors could encounter one of Haiti’s commissioners to the fair, the famed Black American Frederick Douglass, who had recently ended his tenure as the U.S. Ambassador to Haiti. The Haiti pavilion also became the only site where visitors could learn about Black Americans, as the fair’s creators had declined efforts to showcase their accomplishments. With Black Americans erased from the nation’s narrative of progress, Douglass and others worked to keep them visible, turning the pavilion into a hub of advocacy in the months following Fannie Barrier Williams’s historic speech.

Williams’s address was not a spontaneous or isolated event, but the culmination of years of effort to include Black women’s voices in planning of the Columbian Exposition. Although the U. S. Congress had established a Board of Lady Managers to integrate women’s perspectives into the fair, the all-white board and other committees repeatedly excluded Black voices. By late 1891, Williams had become part of a small interracial group that finally made headway, securing a promise that two Black women would be included on the planning committees. A month before the fair opened, Williams had established herself as an important local voice: according to historian Wanda Hendricks, she was tasked with being the liaison between Black women and the white women administrators, a role that directly paved the way for her May 18 address. With her speech, Williams turned months of negotiation into a public statement that placed Black women squarely on the world stage.

In her speech, Williams reminded her audience that it had been just three decades since the Emancipation Proclamation freed enslaved Americans. She drew attention to the advances made by Black women in that time, emphasizing their religious life and drive for education. Williams wanted her audience to understand that Black women were American women in every way: “our women have the same spirit and mettle that characterize the best of American women.” She framed these achievements not as endpoints, but as indications that Black women could accomplish even greater things if given the chance. The Columbian Exposition celebrated the United States as a nation of progress, and Williams deliberately used that language to argue that progress could not be measured without the inclusion of Black women.

But Williams also made it clear that achievement alone was not enough. Discrimination, she emphasized, limited Black women’s job opportunities, and their contributions were largely ignored by white Americans. “We have never been taught to understand why the unwritten law of chivalry, protection, and fair play…must exclude every woman of a dark complexion.” Williams believed that her speech at the World’s Congress of Representative Women was a first step in change. If this “parliament of women” achieved its goals, she said, then “women of African descent in the United States will for the first time begin to feel the sweet release from the blighting thrall of prejudice.”

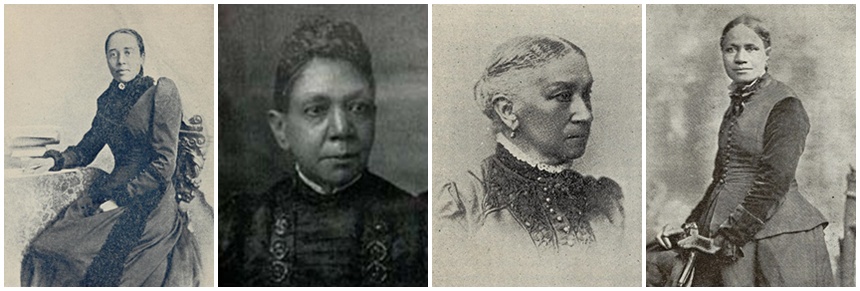

Williams was not alone. In the days that followed, the Black educators and activists Anna Julia Cooper, Fanny Coppin, Sarah Early, and Frances Harper addressed the congress, reinforcing Williams’ argument that Black women’s intellectual, civic, and political contributions demanded recognition.

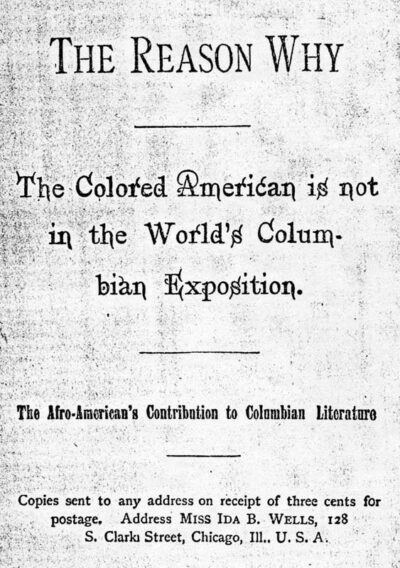

In August, Douglass, Ida B. Wells, and two others authored and printed 10,000 copies of a pamphlet with prefaces in French, German, and English, entitled The Reason Why the Colored American is not in the World’s Columbian Exposition. It was a crash course on the ways Black Americans were being systematically excluded not just from the fair, but from full participation in American citizenship, through disenfranchisement, the convict lease system, and the violence of lynching. While celebrating Black progress, the pamphlet also detailed the efforts to include Black Americans in the Columbian Exposition and the denial they encountered. The vision of progress on display in the White City, the authors argued, was incomplete because it ignored Black citizens’ contributions and rights. The pamphlet provided context and authority for visitors to the Haiti pavilion or any informal gathering of Black leaders, turning what might have seemed like an isolated presence into part of a larger, purposeful protest. The pamphlet did not replace the work Williams began in May, but built on it.

By late October, 27 million people had encountered the world at the Columbian Exposition. The mayor’s assassination two days before closing gave the festivities a somber end. In time, the buildings were mostly dismantled; the World’s Congress Auxiliary that housed the Congress of Representative Women became the Art Institute of Chicago’s permanent home.

After the fair, Williams continued her work, turning visibility into institution-building. She spoke again at the World’s Congress of Religions, broke barriers in the Chicago Woman’s Club, helped found national Black women’s organizations, and later became a founding member of the NAACP.

For four decades after the fair, Williams lived the principles she advocated, pursuing progress through visible, active civic engagement. Speaking out was not a one-time event but a persistent fight to make America live up to its highest ideals for all its citizens. From the World’s Congress stage to decades of activism in Chicago and beyond, Fannie Barrier Williams showed that speaking truth and insisting on being seen could itself pave the way for change.

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

During post-Civil War history (in high school) , the 1893 World’s Fair was largely glossed over, focusing on all the possibilities the coming electrical revolution would bring, particularly for lighting, and the beautiful (but distracting), Ferris Wheel. Nothing wrong with that, with the Industrial Revolution well underway, but far from a the complete story. The easy, fun parts are, well, easier, and more fun to tell.

Fannie Williams had to overcome a lot to get where she did, well before the ’93 Fair. She had other powerful Black women (pictured above) that calmly and methodically worked together towards the common goal of Black women having their full share in America citizenship, and all it had to offer.

Although I have no way of knowing, I would like to think (and would hope) White women with overlapping commonalities of inequality also holding them back, were supportive of Black women in opening doors, helping move things forward that would be mutually advantageous to both races of women.