Saturday Evening Post History Minute: The Greatest Political Comeback in American History

Featured image: Warren Harding and Calvin Coolidge (Library of Congress)

Is 100-Year-Old Wisdom Still Relevant?

“When a father gives his son good advice, he is probably as wise as the sages of old,” Edgar Watson Howe wrote in this magazine 100 years ago. “Few children go astray as the result of taking the advice of a father or mother.”

And yet: “I don’t know which is the more objectionable, an old man’s conceit because of his wisdom, or a young man’s because of his youth.” What Howe’s aphorisms may have lacked in consistency, they made up for in volume.

If your grandparents or great-grandparents lived in the U.S. a century ago and displayed an indestructible ethic for thrift and hard work coupled with animosity for shiftlessness, they might have absorbed the work of the prolific and quotable Howe.

Like a lot of “crackerbox philosophers” of his time, Howe assembled humorous columns and stories from the folksy lessons of his rural Midwestern life. He wrote about the peculiar inhabitants of middle America’s small towns in his “nonfiction novels” like The Anthology of Another Town, and he gave regular opinion and advice in his nationally-circulating E.W. Howe’s Monthly, “devoted to indignation and information.” Although Howe has been functionally wiped from the American consciousness, his sage quips were all the rage in the early 20th century, reprinted in papers from coast to coast regularly. Mark Twain praised Howe’s unique depictions of small-town life, writing, “you may have caught the only fish there was in your pond.”

“Millions of men have lived millions of years and tried everything,” Howe wrote. “Anyone who bets on his judgment against the judgment of the world will be punished for folly.” But his own judgment met plenty of skepticism.

In Howe’s writings for The Saturday Evening Post, he replicated his “common sense” approach to life that praised grit and persistence and pitied his lazier peers who just couldn’t see that “success is easier than failure.” His hard-knock ethical code wasn’t roundly received as scripture. Howe’s critics pointed to the Panic of 1893, widespread poverty among hard-working immigrants, and the inescapable hardships of the Great Depression as proof that reality was antithetical to his fixation on self-reliance.

Howe insisted that the old sentimental story of the poor man jailed for stealing bread for his starving family was pure fiction, that any such criminal would be met with a system ready to “relieve his distress” instead of persecuting him. Writing in The Nation in 1934, critic Ernest Boyd claimed the “fundamental falsity” of Howe’s ideas “has been obvious to every thinking person since the beginning of the Industrial Revolution, at least.”

After his death, in 1941, Howe’s son wrote about him in a Post article titled “My Father Was the Most Wretchedly Unhappy Man I Ever Knew.” Gene Howe confessed that he had been terrified of his father’s wrath his entire life, describing the elder Howe’s rigid positions against women and religion. “I do not believe there ever lived a writer who could hurt as he did,” Gene Howe wrote, “who was so blunt and direct, and who could lacerate so deeply. I know he did not realize this himself.”

Still, Howe’s son contended that his father operated with the sole purpose of saving humanity from itself by publicizing far and wide the “virtue of selfishness.”

E.W. Howe’s essay “A New Traveler Over an Old Road,” printed 100 years ago in the Post, offers glimpses of a controversial thinker’s “accumulated wisdom”:

- “The devil is dead; but he never took so much interest in your misconduct as your neighbors did. And the neighbors are still here to watch you.”

- “Our list of wrongs is becoming too long. It is evidence that we either invent wrongs or are too lazy to remedy them. Whatever is palpably wrong with your plumbing, your teeth, your drainage, your county, city, congressional district, state or nation, should be fixed, and usually can be. It is an inefficient man who forever fusses about his wrongs and does nothing.”

- “If there is a little merit in a printed composition — a suggestion of an idea, a clever expression of an old one — it is all you have a right to expect. If it is dull, as is usually the case, dismiss it without prejudice against the poor author, who is probably a bundle of weaknesses and prejudices, as you are. Writing is not a divine art; it is as tiresomely human as is conversation. What is there to eat that has not been eaten? What is there new to say in print?”

- “Don’t get yourself in a situation where you need vindication. After a complete vindication a good many will have doubts of your innocence.”

- “Probably every man has a little superstition; I doubt if even the bold editor of The Truth Seeker entirely escapes. Those who do not pray, knock on wood. I sometimes think that, from my helplessness as a fool, I have sacrificed my life a dozen times, and that something that came in on an east wind saved me. The three wise men came from the east long ago, but there are others there to this day.”

- “I do not care to fool any man; when he discovers I have fooled him he will do me more harm than my cunning did me good. If you get the best of a bargain by cunning, better give it back before the policeman arrives.”

- “Exaggerating the rewards of virtue is in bad taste. A man may practice all the virtues and not be notably prosperous or happy; but he will get along better than the idle or unscrupulous. A good man will have pains and difficulties as surely as the wicked man, but he will have fewer of them. This is about all that may be truthfully said in favor of virtue.”

- “A new idea is not enough; it must be a good idea also. I have no wish to write a well-rounded or eloquent sentence that will cause anyone to believe that which is untrue or unfair.”

Featured image: “The Philosopher of Potato Hill,” 1905-1910, The Kansas Historical Society

Saturday Evening Post Time Capsule: September 1920

See all of our Time Capsule videos.

Credits:

The Flapper, 1920 (Selznick Pictures Corporation, via Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 license)

Oliver Lodge (Lafayette Ltd. via the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license)

Arthur Conan Doyle spirit photograph and poster (The Arthur Conan Doyle Encyclopedia)

Music: Wyoming Lullaby by Mayfair Dance Orchestra, 1920

Featured image: Everett Collection / Shutterstock

100 Years Ago: The Women Who Ran Off with the Circus

In a time before television or Twitter, the traveling circus was a dominant, all-American form of entertainment. The young and old, rich and poor alike would gather to witness the exotic animals and superhuman acrobatics under the big top each summer. Traveling circuses would shut down entire towns with their parades and engulf the country in “sawdust and spangles.”

The larger-than-life showmen behind the country’s great circuses, like P.T. Barnum, James Bailey, and the Ringling Brothers, are still household names, but many of the performers, daredevils, and animal trainers who astounded their audiences and made weekly headlines have been forgotten.

Part of the appeal of circus folk lay in the mystery surrounding them. Who were they and where did they come from, these people who descended on the most provincial towns with strange talents and glamorous costumes? At the turn of the century, the circus spotlight began to shine on women, highlighting their athletic talents juxtaposed with dainty beauty.

Historian Janet M. Davis writes in The Circus Age that “In an era when a majority of women’s roles were still circumscribed by Victorian ideals of domesticity and feminine propriety, circus women’s performances celebrated female power, thereby representing a startling alternative to contemporary social norms.”

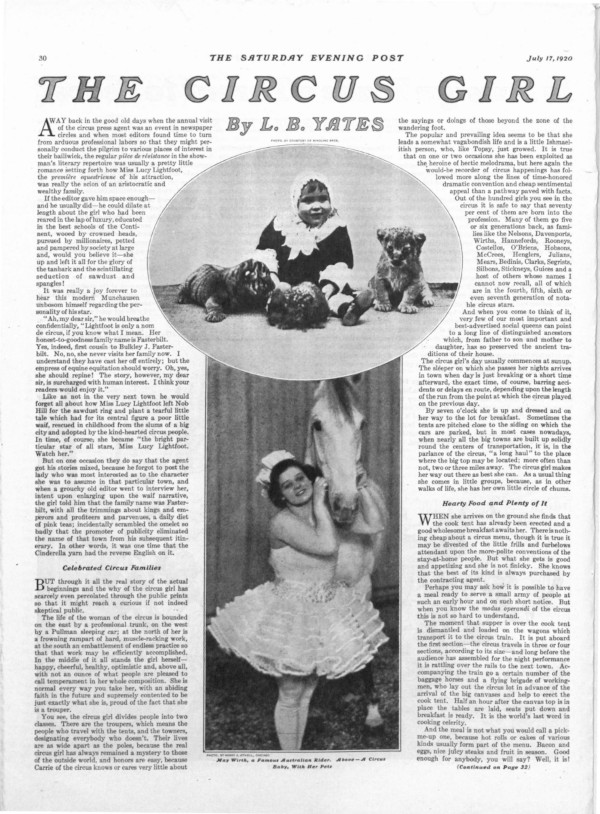

According to “The Circus Girl,” an article by L.B. Yates that appeared in the Post 100 years ago, the intrigue of the female circus performer was heightened by press agents who sowed fictional accounts to local papers of either some rich society girl or poor waif who had found a calling as a trick horse rider in the circus. It was usually a fabrication, as Yates claimed, since the vast majority of circus performers were born into the profession.

But the treatment of this new crop of female performers, in the press and in the culture, was a tightrope act of sorts. The circus offered a home for some outsiders and castaways and provided independence and adventure for its female stars. For audiences, it afforded titillating, exotic glimpses of the limits of the human body while promising to uphold decency in its ranks.

The women of the American circus during its golden age worked tirelessly to perfect their acts, stealing shows and breaking stunt records at a unique time in history that straddled the old conventions with the new promise of suffrage and feminism.

Lillian Leitzel

“I resent having people come to my tent, stare at me as though I were a freak and then turn away laughing, as if they’d seen some wild animal,” the famous aerialist Lillian Leitzel told the Post in 1920. “They seem to assume that circus people have not got beyond the primitive stage of the cave man and are an aggregation of unlettered louts wholly devoid of the commonest sense of social amenities.”

Leitzel was indeed rich in social amenities, and she was also just plain rich. According to historian Janet M. Davis, the performer was making up to $200 a week in 1917 with Ringling Brothers (worth more than $4,000 in 2020), and it wasn’t uncommon for female circus stars to rake in more than their male counterparts. She had her own train car that contained a piano, and at each stop she would dress in her own private tent. By the 1920s, she was pulling in $500 per week, according to John Culhane in The American Circus.

Known as a brassy primadonna, Leitzel grew up in a Czech circus family and began in the gymnasium at 3 years old. Her signature act was to bound up the rope and hold her hand in a loop while throwing her body up and around, dislocating her shoulder over and over again as she performed her “one-arm planges.” As a percussionist carried on a drumroll, the audience would count her swingovers, one time as many as 249.

“Accidents? Oh, well, they’re liable to happen any time,” Leitzel told the Post. “But I never think of that. Whenever a performer gets to studying about the chances he or she is bound to take, he has outlived his usefulness. An acrobat must have hundred per cent nerves.”

She entertained other elite performers, senators, businessmen, and especially children in her private car. She was known for giving parties for all of the circus children and lavishing gifts and sweets on them, possibly because she was stripped of a childhood herself, according to Culhane.

Leitzel encouraged women to exercise to stay healthy, in spite of lingering Victorian notions that athleticism made women ugly and manlike. “Down with the corset,” she told newspapers in 1923. “Put a brick in the atrocious garment and hurl it into the Niagara River.” She encouraged women to take up swimming or some other sport they enjoyed, promising “you can eat what you want and work off the energy in exercise.”

Leitzel married the Mexican trapeze artist Alfredo Codona, and their passionate celebrity marriage was rife with jealousy and resentment. When Leitzel traveled to Europe in 1931, Codona went separately with an equestrian with whom he was having an affair. In Cophenhagen, Leitzel was performing her one-arm planges when the brass ring she was holding snapped, and she fell 20 feet onto her head. Although she insisted on continuing her act, her handlers sent her to the hospital. She died the next morning from a concussion.

Mabel Stark

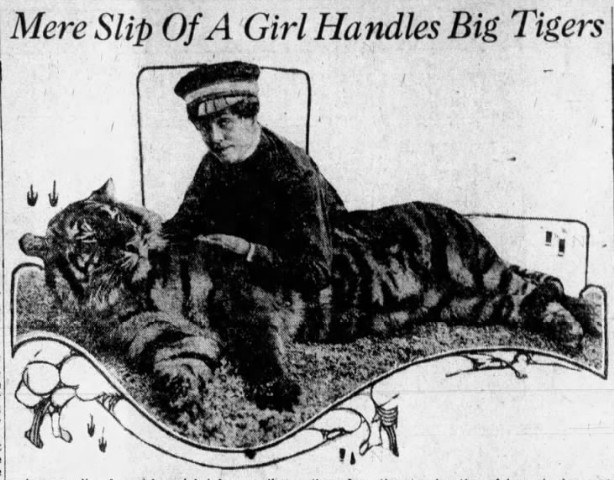

Mabel Stark was working as a nurse — with a stint as a burlesque dancer — when she found a calling to work with big cats in Venice, California around 1911. She stumbled onto the grounds of the traveling Al G. Barnes Circus and became obsessed with Bengal tigers. Stark joined the show, and within a few years she was a big cat trainer. Stark was the first American woman to take up the dangerous profession, let alone to achieve such renown.

Over the years, she became one of the most famous tiger (and lion and panther) tamers in the world, joining the Ringling Brothers in 1920. Newspapers gushed over her unique wrestling act. Stark would roll around with any of her 18 tigers, giving the impression of a perilous struggle.

Although Stark spent most of her time with her cats and treasured them dearly, she never lost sight of the risk of working with tigers. She gave some insight to a Public Ledger reporter in 1923: “The tone of the voice, the determination of it, has a great deal to do with subduing wild animals. Don’t let uncertainty or fear creep into your tones, or you’re gone. A great life, so to speak, if you don’t weaken.”

As with many who work with predator animals, Stark sustained serious injuries throughout her career (according to a profile in the St. Louis Globe-Democrat in 1950). In Maine, she was mauled in the ring and required 378 stitches. In Arizona, she was bitten by a tiger named Nellie and finished her act with a limp left arm. In spite of it all, she continued to defend her fierce friends and the connection she had with them.

Stark’s story ultimately ended in tragedy. After retiring from the circus in the late 1930s, she settled in at an amusement park called Jungleland. Stark was let go for insurance reasons, and then one of her tigers escaped and was shot. The devastated near-80-year-old took her own life.

May Wirth

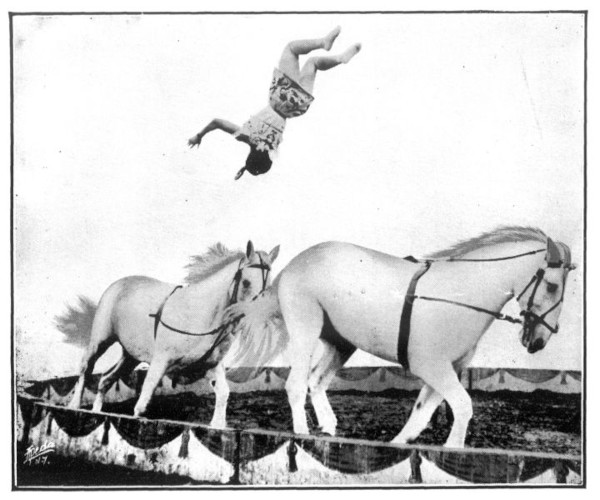

Billed as “The World’s Greatest Rider,” May Wirth was only 17 when she made her first appearance in the Ringling Brothers’ show at Madison Square Garden. The Australian transplant wore a giant hair bow and leapt from horse to horse, completing flips and twists that dazzled audiences and — sometimes moreso — other riders.

Wirth was an orphan who performed as a five-year-old contortionist and was eventually adopted by the down-under circus rider Marilyas Wirth Martin. According to the Braathens, two Madison, Wisconsin circus buffs writing in The Capital Times in 1973, Will Rogers witnessed young Wirth riding in her home country and predicted “the day would come when there would be but two types of bareback riders in the world, May Wirth and all the others.”

When the Braathens asked about her legendary forward somersault, Wirth recalled that Mr. Ringling was skeptical that anyone could complete such a trick, and when she tried it for him: “I missed it and fell on my back right in front of Mr. John. I got up like a streak of lightning, ran and vaulted onto the horse again and did the stunt over for him, this perfectly, and did the somersault feet to feet. That earned me my first season’s contract with John Ringling.”

The sweetheart of the circus made the front page of The New York Times after an unfortunate slip in 1913 caused her to be dragged around the track behind her horse by her feet. Nine years later, the paper reported that she had accepted the challenge of riding a bull, and better yet: “Miss Wirth not only rode the bull, reputed to be a most ferocious beast, 3 years old and weighing 2,400 pounds, but she rode him standing on her hands upon his back.”

Wirth retired from the big top in 1937 and went to live with her mother in New York. She later moved to Sarasota, where the Ringling Museum and Circus Hall of Fame was located. She was inducted in 1964.

Featured image: 1890-1900, Calvert Litho. Co., Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, D.C.

The Circus Age by Janet M. Davis

The American Circus by John Culhane

Women of the American Circus, 1880-1940 by Katherine H. Adams and Michael L. Keene