1961: The Year That You Didn’t Know Changed Music

If you follow the history of music, particularly popular music, you know that certain years always recur in the conversation. 1936 marked the first of Robert Johnson’s legendary blues recordings, while 1956 marked the ascent of Elvis. You know that The Beatles did Sullivan in 1964, Woodstock happened in 1969, and that The Sugarhill Gang recorded the first hip-hop song to hit the Top 40, “Rapper’s Delight,” in 1979. Those years and many others always swirl about the conversation, but one year is consistently overlooked. In retrospect, 1961 is hugely important, as it set the stage for the rest of the decade and for decades to come. Let’s turn back the clock to the year that Berry signed the girls from the Projects, two former school friends met up again, Patsy went pop from the hospital, and four lads played the Cavern Club for the first time.

1. January: Motown Signs The Supremes

“Where Did Our Love Go” (Uploaded to YouTube by The Supremes)

They were originally called The Primettes, a girl-group companion to The Primes, which featured Paul Williams and Eddie Kendricks. The four original members of the Primettes were Betty McGlown, Florence Ballard, Mary Wilson, and Diana Ross; several of the girls lived in and around the Brewster-Douglass Housing Projects in Detroit. They sang together for two years (McGlown left, and was replaced by Barbara Martin). During this time, Ross got her former neighbor, Smokey Robinson, to get them an audition with Motown label head Berry Gordy. He didn’t sign the girls at first, thinking them too young. But the group persisted, showing up at the label HQ and eventually getting to do handclaps and more on records. By January of 1961, Gordy agreed to sign them, with a catch. The Primes were no more, with Williams and Kendricks joining The Temptations, so Gordy felt they needed a new name. Ballard picked one from a list. Forever after, they’d be The Supremes.

2. January 30: The Shirelles Go #1

The Shirelles hold the distinction of being the first Black all-girl group to hit #1 on the Hot 100. The song was “Will You Love Me Tomorrow.” Obviously, the #1 was incredibly important for the glass ceiling that it shattered and the opening that it created for groups to follow (like the newly signed Supremes). The song was a big hit internationally, making the Top 5 in countries like the U.K. and New Zealand. “Will You Love Me Tomorrow” was also the first #1 for its writers, the then-married couple of Gerry Coffin and Carole King. The pair would write 30 hit songs together throughout the 1960s.

3. February: Motown Sells a Million

Berry Gordy positioned his Motown label as “the sound of young America.” He put together a studio system with top-notch writers and musicians, and signed talent local to Detroit that he could elevate into stars. One of those early stars (and songwriters) was Smokey Robinson of the group The Miracles. In 1960, Gordy and Robinson co-wrote “Shop Around,” a song for The Miracles that would take the label into previously uncharted territory. It went to #2 on the Hot 100 singles, #1 on the R&B chart, and, by February of 1961, became the first Motown single to sell a million copies. “Shop Around” was a statement of legitimacy for Gordy’s system and growing stable of artists, paving the way for Motown to earn the nickname “Hitsville, U.S.A.”

4. February: The Beatles Play The Cavern Club

It wasn’t the first time for everybody. John Lennon had played the club with The Quarrymen in 1957; Paul McCartney played with them in 1958. Future bandmate Ringo Starr had played with Rory Storm and the Hurricanes in 1960. But the first time that The Beatles (and George Harrison) played there was February 9, 1961. At that point, the line-up was Lennon, McCartney, Harrison, Stuart Sutcliffe, and Pete Best. The Beatles had just returned from their long residency in Hamburg, Germany, and their constantly evolving showmanship combined with their youthful energy convinced everyone that something about that band was special. Sutcliffe would leave that summer, and Best would be replaced by Ringo Starr in 1962. Between their first date and August of 1963, The Beatles played The Cavern Club 292 times, building the tight unit that would take the world by storm.

5. February: Reprise Begins Releasing

Frank Sinatra remains one of the biggest names in the history of music. In 1960, he did something that only an artist of his clout could do: he formed his own label. Reprise Records would be a place where Sinatra could exercise his artistic freedom more thoroughly, while also creating a home base from which his friends, like Sammy Davis, Jr., and specially selected acts could release records. Both Sinatra and Davis began releasing singles and albums on the label in 1961; others quickly joined the line-up, including Dean Martin, Bing Crosby, Duke Ellington, and Rosemary Clooney. The set-up is what earned Sinatra the nickname “The Chairman of The Board.” One young artist signed to Reprise in 1961 would go on to make a big splash during the rest of the decade; that was Sinatra’s daughter, Nancy. Signed at age 20, she would blow up mid-decade as a music and style icon with classic hits like 1965’s “These Boots Are Made for Walkin’.”

6. July: Billboard Separates the Charts

In 1961, there were still radio stations that wanted to avoid any association with the label “rock and roll.” Billboard magazine, which was the compilation source for the most widely read and acknowledged charts tracking popular music, tried to accommodate stations by creating a separate chart that would leave out up-tempo hits from the rock genre. The so-called “Easy Listening” chart debuted in July of 1961. While some rock or R&B artists would cross over with ballads, the general sound and feel of the chart was essentially a generational split. Younger listeners would come to consider “Easy Listening” to be “old people’s music.” That fracture between younger and older audiences would become one of the cultural engines of the entire decade. The chart has changed names many times over the years, adopting monikers like “Middle-Road Singles” and “Pop-Standard Singles” before settling on “Adult Contemporary” in 1983.

7. August: Patsy Cline Crosses Over from Her Hospital Bed

“I Fall to Pieces” (Uploaded to YouTube by Patsy Cline)

In June of 1961, country star Patsy Cline nearly died when the car she was traveling in with her brother was hit head-on by another driver. With a dislocated hip, a broken wrist, and more injuries, Cline underwent emergency surgery. Her initial prognosis was bleak, but Cline survived and spent a month in the hospital recovering. While she was in bed, the single that she’d released in April, “I Fall to Pieces,” surged on the Country and Western chart. By August, it had hit #1 Country and crossed over to the Pop charts, where it would peak at #12. Before the end of the month, she would record a new song by a struggling songwriter for release in October (you’ll see).

8. October: West Side Story Takes Over

West Side Story was a huge hit film in 1961, but the soundtrack was impossibly big. Released in October, the album would sit at #1 for a ridiculous 54 weeks (yes, more than a year). Remarkably, it would remain the best-selling album of the ENTIRE DECADE . The only other album to have a similar run at #1 is Michael Jackson’s Thriller, which spent 37 (non-consecutive) weeks on top. The Broadway show (which launched in the ’50s) and the subsequent film were inextricable from 1960s culture, and remain a crucial piece in the legacies of Leonard Bernstein, Stephen Sondheim, and Jerome Robbins.

9. October 16: “Crazy” Is Released

“Crazy” (Uploaded to YouTube by Patsy Cline)

Patsy Cline’s follow-up to “I Fall to Pieces” hit stores on October 16. The song was “Crazy.” It went #2 Country, #9 on the Hot 100, and #2 on Easy Listening. It established Cline as a firmly entrenched crossover star. Though she would die in a plane crash in 1963, Cline left a legacy as a top-flight vocalist; she had also mentored her friend, Loretta Lynn, who would become a dominant force in Country throughout the decade.

The other side-effect of “Crazy” is that it solidified the career of its songwriter, Willie Nelson. The song became the biggest juke-box hit of all time, and established Nelson as an in-demand writer. He signed with Liberty Records in 1961 and started releasing his own hit singles the following year.

10. October 17: Mick and Keith Meet Again

Mick Jagger and Keith Richards met at age seven in 1950 when they were both schoolchildren in Dartford, England. They went to school together until the Jagger family moved in 1954. Coincidence (or maybe fate; okay, definitely fate) put them both on the same platform at the Dartford railway station. The two old friends started talking; Jagger had records by Muddy Waters and Chuck Berry with him, which excited fellow blues fan Richards. That meeting led directly to the pair forming their first group together, the Blues Boys. By the next year, they would be in a new group with Brian JonesDick Taylor, Ian Stewart, and, eventually, Charlie Watts; that group would come to be called The Rolling Stones.

11. November 20 & 22: Bob Dylan Records His Debut Album

Bob Dylan had been gigging in New York when he was signed to Columbia Records by John H. Hammond. Hammond produced Dylan’s self-titled debut, which would see release the following March. The album includes two original songs; the remainder of the album is a set of covers largely drawn from folk tradition. Bob Dylan didn’t make great waves upon its release, but the hit of what would come is there. His next album, The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan, would open with “Blowin’ in the Wind.”

12. November 27: The Beach Boys Debut with “Surfin’”

“Surfin’” (Uploaded to YouTube by Beach Boys)

If your parents went out of town and left you food money, but you blew it all on musical instruments, you’d probably be grounded for eternity. Then there’s the Wilson brothers (Brian, Carl, Dennis), their cousin (Mike Love), and their friend (Al Jardine). When the Wilson boys’ parents took some friends to Mexico City for a few days over Labor Day weekend, the boys used the money to rent instruments and equipment to work out a song that Brian and Mike wrote. Dubbed “Surfin’,” the upbeat tune had its first performance for the shocked Wilson parents when they returned home. The Wilsons’ father, Murry, himself a musician and songwriter, said he’d manage the group. They ended up recording the song for the Candix label, using the name The Pendletones, in October. When they got the pressed singles back, the label’s PR man had changed their name. The Wilsons, Love, and Jardine had become The Beach Boys. “Surfin’” hit #75 on the Hot 100, but the following year, they took “Surfin’ Safari” to #14, the first of their 36 Top 40 singles.

ENCORE: Births

1961 wasn’t just important for what happened; it was important for who happened. A shocking number of musicians born in 1961 would have a major impact on the shape of various forms of American popular music. Those people include: Suggs and Mark Bedford (Madness); Gillian Gilbert (New Order); Margo Timmins (Cowboy Junkies); Vince Neil (Mötley Crüe); Henry Rollins (Black Flag; Rollins Band); Dez Cadena (Black Flag); Andy Taylor (Duran Duran); Slim Jim Phantom and Lee Rocker (The Stray Cats); Roland Gift (Fine Young Cannibals); Enya; Nick Heyward (Haircut 100); Melissa Etheridge; El DeBarge; Tom Araya (Slayer); Kim Deal (The Pixies; The Breeders); Kelley Deal (The Breeders); Boy George and Roy Hay (Culture Club); Alison Moyet; Jimmy Somerville (Bronski Beat); Dennis Danell (Social Distortion); Curt Smith and Roland Orzabal (Tears for Fears); Terri Nunn (Berlin); Toby Keith; Andrew Fletcher and Martin Gore (Depeche Mode); Guru (Gang Starr); Keith Sweat; Gary Cherone (Extreme; Van Halen); Rikki Rockett (Poison); Dave “The Edge” Evans and Larry Mullen Jr. (U2); Jon Farriss (INXS); Dean DeLeo (Stone Temple Pilots); Scott Travis (Judas Priest); Dave Mustaine (Metallica; Megadeth); Bilinda Butcher (My Bloody Valentine); Wynton Marsalis; Randy Jackson (The Jacksons); k.d. lang; Leif Garrett; Jim Brickman; Jim Reid (The Jesus & Mary Chain); Sara Dallin and Keren Woodward (Bananarama); Jill Sobule; Lloyd Cole; Doug Hopkins (Gin Blossoms); Billy Duffy (The Cult); Melle Mel (Grandmaster Flash & The Furious Five); Maxi Priest; Kip Winger (Winger); Jim Martin (Faith No More); Debbi Peterson (The Bangles); Billy Ray Cyrus; and Darryl Jones (The Rolling Stones).

Featured image: Katherine Welles /Shutterstock

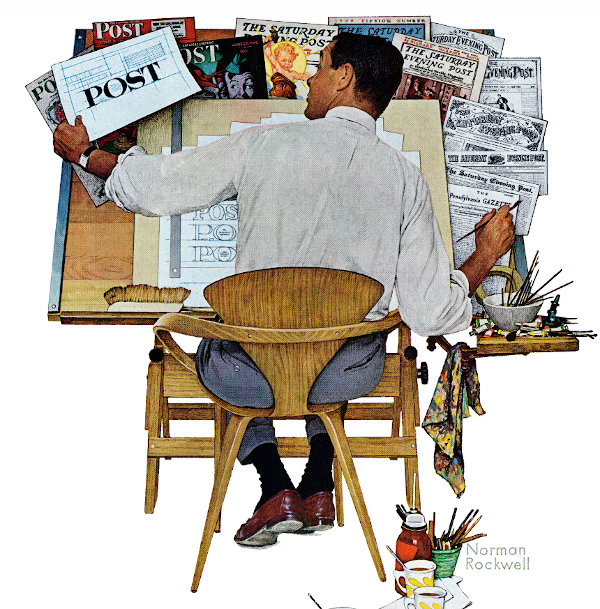

Rockwell Files: Freshening Up Our Logo

To reflect its new, modern style in 1961, the Post underwent a major redesign. The magazine changed its editor, layout, typography, and, especially, its logo. Norman Rockwell celebrated the change on the September 16 cover by painting Herbert Lubalin, who created the new Post logo, at his drafting table. The cover was a humorous allusion to a cover Rockwell had painted in 1938 in which the artist portrayed himself surrounded by discarded sketches, staring at a blank canvas and scratching his head in search of a fresh idea.

To emphasize the Post’s long history on this cover, he tucked copies of 11 previous Post cover illustrations around the work table. He even included a copy of the Pennsylvania Gazette, founded by Benjamin Franklin in 1728, from which the Post was born.

A cover recalling the Post’s long history is appropriate, we feel, as we approach 2021 — a very special year for the magazine. On August 4, 2021, we will be 200 years old. We think Norman would be proud. We certainly are.

This article is featured in the November/December 2020 issue of The Saturday Evening Post. Subscribe to the magazine for more art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

Featured image: Norman Rockwell / © SEPS

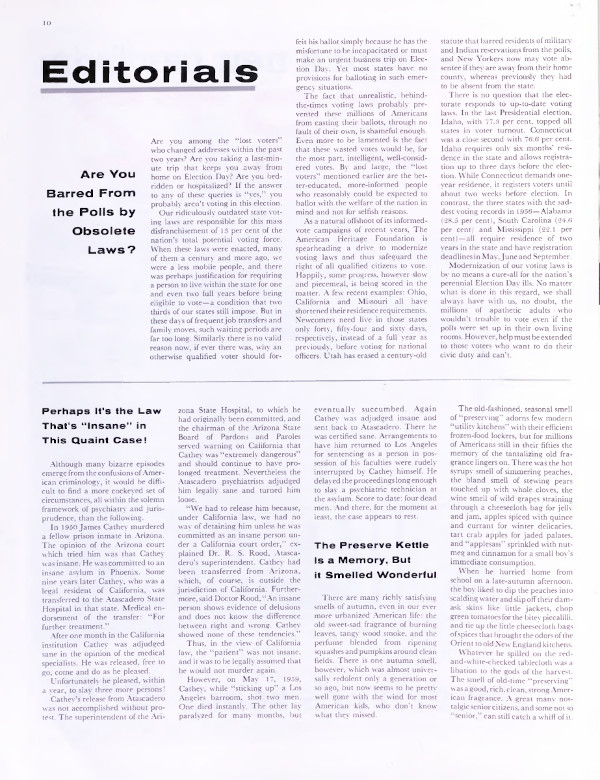

Are You Barred from the Polls by Obsolete Law?

In this 1960 editorial, the Post urged states to eliminate stringent residency requirements and other rules that disenfranchised voters.

Our ridiculously outdated state voting laws are responsible for a mass disfranchisement of 13 percent of the nation’s total potential voting force.

When these laws were enacted, many of them a century and more ago, we were a less mobile people, and there was perhaps justification for requiring a person to live within the state for one and even two full years before being eligible to vote — as most states still do. But in these days of frequent job transfers and family moves, such waiting periods are far too long.

Similarly there is no valid reason why an otherwise qualified voter should forfeit his ballot simply because he has the misfortune to be incapacitated or must make an urgent business trip on Election Day. Yet most states have no provisions for balloting in such emergency situations. Help must be extended to those voters who want to do their civic duty and can’t.

—“Are You Barred from the Polls by Obsolete Law?,” Editorial, November 12, 1960

This article is featured in the November/October 2020 issue of The Saturday Evening Post. Subscribe to the magazine for more art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

Featured image: Constatin Alajalov / SEPS

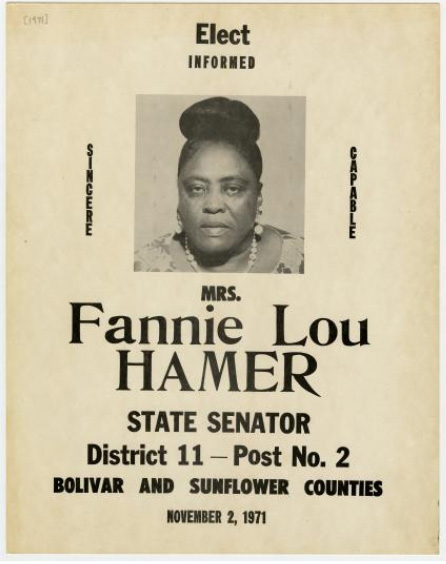

Fannie Lou Hamer’s War on Voter Suppression

Lyndon B. Johnson was distressed a few days before the start of the 1964 Democratic National Convention. In a presentation to the party’s Credentials Committee in an Atlantic City hotel ballroom, a Black Mississippi woman named Fannie Lou Hamer was giving a disturbing account of her various past attempts to exercise her right to vote. She was “sick and tired of being sick and tired.”

Hamer, then 46 years old, had been the youngest of 20 children in her family, leaving school in sixth grade to work on Mississippi plantations. She had been poor her entire life, and suffered from polio as a young girl. Just three years earlier, she had been sterilized against her will while hospitalized for a minor surgery. But her address to the 108 committee members that day recounted, in sickening detail, numerous instances of violent institutional repression that had prohibited Hamer from participating in her country’s — and the Democratic Party’s — democratic process.

She first failed the arcane and discriminatory literacy test that was administered to African Americans in 1962. Then, she was on a busload of hopeful Black voters that was pulled over for being the wrong color (too yellow). Then, the plantation owner kicked her off the land she sharecropped (for attempting to register to vote). Then, in 1963, she was arrested with several others after attending a voter registration workshop. While in jail, she was brutally beaten with a blackjack by other prisoners at the orders of a state trooper who told them to, according to this magazine, “Make the bitch wish she was dead.”

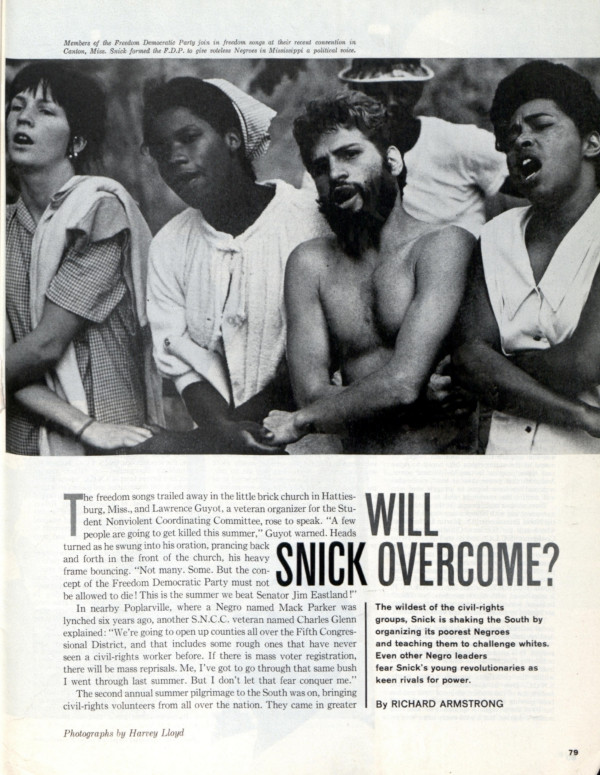

At the Democratic Convention, Hamer was speaking on behalf of the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party, a grassroots political project that aimed to replace the state’s elected delegation on the premise that it was illegally selected with a segregated vote — a “white primary.” Less than seven percent of eligible Black adults were registered to vote in Mississippi in 1964. With the cooperation of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC or “Snick”), NAACP, Southern Christian Leadership Conference, and the Congress of Racial Equality, activists in the South organized tens of thousands of mostly Black, poor and working-class people in a precinct-level effort to subvert the all-white Democratic stronghold in the state.

President Johnson worried that the MFDP — and a potential interracial delegation — would alienate the South’s white Democratic voters, sending them into the arms of the Republicans. During Hamer’s speech, he called an impromptu press conference, leading many to think he was about to announce his running mate. Instead, he gave a commemoration of President Kennedy, who had been assassinated nine months earlier. The television networks still played Hamer’s speech, though, during their primetime broadcasts. Their viewers saw the poor Black sharecropper’s impassioned indictment of her country: “Is this America, the land of the free and the home of the brave, where we have to sleep with our telephones off the hooks because our lives be threatened daily, because we want to live as decent human beings, in America?”

Hamer’s testimony was an uncomfortable dose of reality for liberal America. Even today, her story teaches largely unexamined lessons regarding the background work of the civil rights movement and its many proponents. As scholar Maegan Parker Brooks wrote in her recent biography of Hamer, “The life story of a disabled, impoverished, middle-aged black woman from the rural Mississippi Delta challenges widespread perceptions of who participated in — as well as how they influenced — mid-twentieth century movements for social, political, and economic change.” Hamer is not a household name like Martin Luther King, Jr. or John Lewis, but her role in this transformational period of American history shows us what was at stake, and indeed still is.

Hamer didn’t appear at the 1964 Democratic National Convention out of thin air. Along with three other Black candidates in the state, she ran a primary campaign against the longtime Mississippi representative Jamie Whitten. The Freedom Democrats had been working since the previous fall to both register Black Mississippians and hold straw votes in their own “freedom-registration books” to show what electoral participation could look like in the state where African Americans made up 42 percent of the population. That summer, a profile of Hamer in The Nation posited that “The wide range of Negro participation will show that the problem in Mississippi is not Negro apathy, but discrimination and fear of physical and economic reprisals for attempting to register.”

During the Freedom Summer of 1964, the civil rights groups that made up the Council of Federated Organizations undertook a statewide organizing effort to account for Black non-voters and register as many as possible. They also established Freedom Schools, community centers, and a Freedom Labor Union. At the heart of this undertaking was the oversized contribution of SNCC, the activist group Hamer had worked with diligently since attending a mass meeting in 1962. Hamer traveled around the state, stirring Black audiences with speeches that motivated them to act for their own liberation. (“It’s a shame before God that people will let hate not only destroy us, but it will destroy them. Because a house divided against itself cannot stand and today America is divided against itself because they don’t want us to have even the ballot here in Mississippi.”) At the same time, SNCC’s army of volunteers — largely white college students from the North — were moving around Mississippi organizing for participatory democracy at every level.

In 1965, this magazine covered the student group (“Will Snick Overcome?”), pointing out the markedly more radical approach SNCC employed compared to a group like the NAACP. Arising from the sit-ins of 1960, SNCC was an early opponent of the Vietnam War and decidedly non-hierarchical. While it claimed manpower from the country’s college students, SNCC aimed to cultivate leadership at the community level in its campaigns. The Post recognized this unique tactic of SNCC’s “shock troops,” even if it seemed tedious: “The whole concept of building a political force out of tenant farmers, slum-dwellers and the unemployed is a radical departure from American political norms.”

In response to claims that communists and Marxists — perhaps even foreign ones — were stirring up all of the trouble in the South, Hamer gave a simple response in a speech at a mass meeting in 1964: “People will go different places and say, ‘The Negroes, until the outside agitators came in, was satisfied.’ But I’ve been dissatisfied ever since I was six years old.” Hamer’s lifelong dissatisfaction steered her toward a fight for voter enfranchisement, and later, as Brooks puts it in her biography, fights “against white supremacy, police brutality, sexual assault, segregated education, food insecurity, and health care access” among others.

In June, before the convention, three Freedom Summer organizers — James Earl Chaney, Michael Schwerner, and Andrew Goodman — were murdered near Philadelphia, Mississippi. The Ku Klux Klan had grown its numbers in the area and burned down 20 black churches that summer, many of which were hubs for civil rights activity. The three men had been involved with a church that housed a Freedom School, and several Klansmen, policemen, and a minister conspired to shoot them and hide their bodies. The case was a national outrage, but over the course of the federal investigation eight bodies of Black men were found, several of them civil rights workers as well.

After Hamer made the MFDP’s case to the Credentials Committee at the convention, the Johnson administration countered with a negotiation offer: the MFDP could have two at-large seats (picked by Johnson) without unseating any of the Mississippi delegation, and the party would ban segregated delegations in 1968. Hamer and other Freedom delegates were fuming at the prospect of accepting such a paltry deal, but leaders from the NAACP and SCLC, including Martin Luther King, Jr., advised them to take it. The MFDP unanimously voted against accepting the offer, in an outright rejection of the legitimacy of the Mississippi delegation.

That repudiation is an important aspect of Hamer’s legacy in that it refuses to conform to what author Jeanne Theoharis calls the “national fable” of the civil rights movement: the idea that this era of our history can be represented as a settled legislative triumph featuring a small cast of iconic heroes instead of as a disruptive, radical mass movement against institutional white supremacy. Hamer was not interested in a reassuring narrative for white folks; she wanted liberation.

The next month, Harry Belafonte took a group from the MFDP — including John Lewis and Fannie Lou Hamer — on a trip to Guinea. They were received with a warm welcome, meeting President Ahmed Sékou Touré and touring his palace. On the trip, Hamer wrote in her autobiography, she felt she was treated much better in Africa than in America, and she noticed many of the negative stereotypes she had been led to believe about Africans were incorrect. “So when they say, ‘Go back to Africa,’” she wrote, “I say, ‘When you send the Polish back to Poland, the Italians back to Italy, the Irish back to Ireland and you get on that Mayflower from whence you came and give the Indians their land back.’ It’s our right to stay here and we stay and fight for what belongs to us.”

Featured Image Courtesy of the Archives and Records Services Division, Mississippi Department of Archives and History

“The Kids These Days!” or “The Parents Just Don’t Get It!”

—The following is from “The Younger Set,” Editorial, September 4, 1920

No longer is it true that the young are seen but not heard. Not only do they make themselves heard but they shout down their elders in a daily mounting chorus of derision and scorn. Art, literature, education, and economics — all these are being dominated by the reckless, half-formed judgments of youth.

Progress would die if old men always had their way. But it is no sign of settled brain paths to be aware of the rampage on which youth has of late been engaged. The meaningless smudge and blur that makes up so much of modern art; the strange, tortured language which so many of the younger, newer writers use in place of English; and the rediscovered and previously discarded utopias which a host of youthful reformers are so joyfully recommending — are these not signs that youth has been given — or has taken — its head with a vengeance?

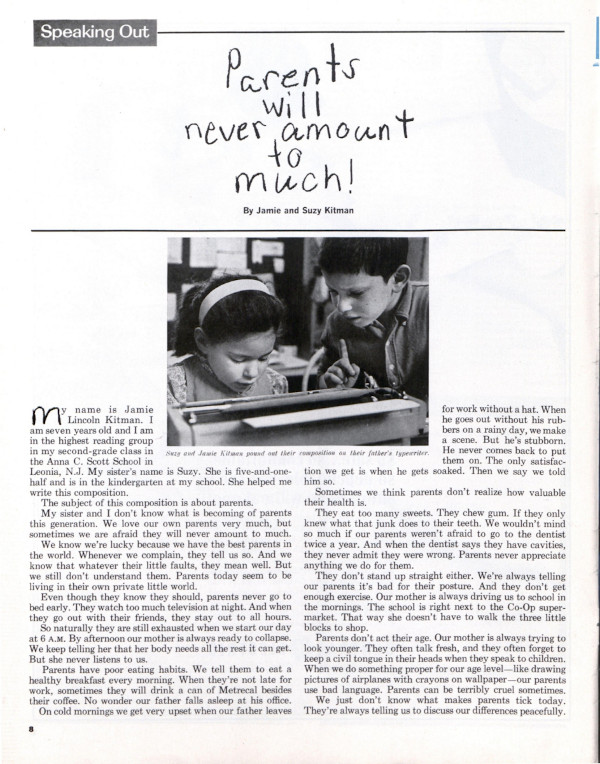

—The following is from “Parents Will Never Amount to Much!” December 19, 1964

My sister and I don’t know what is becoming of parents this generation. We love our own parents very much, but sometimes we are afraid they will never amount to much.

We know that whatever their little faults, they mean well. But we still don’t understand them. Parents today seem to be living in their own private little world.

Even though they know they should, they never go to bed early. They watch too much television at night. And when they go out with their friends, they stay out to all hours.

Parents have too much freedom these days. They are always thinking of ways to get away from us. When our mother goes on a business trip with our father, why do they always take their bathing suits?

We don’t know where our parents picked up all their bad habits. Certainly not from us. It’s probably their friends. We don’t approve of their friends. They wear too much makeup and they drink.

Sometimes we’re afraid we spoil parents by letting them have their way.

—“Parents Will Never Amount to Much” by Jamie and Suzy Kitman, December 19, 1964

Featured image: Everett Collection / Shutterstock

Simon and Garfunkel Burned Their Bridge as They Built It

One of the most celebrated and successful musical duos of all time, Simon and Garfunkel crafted a unique kind of harmony, even if their partnership wasn’t always harmonious. A staple of the 1960s who has experienced reignited interest in several decades since, the pair and their brand of folk-rock thrives even though it’s been 50 years since their last studio album together. And 50 years ago this week, what might be their signature song was in the middle of a six-week run at the top of the charts. Here’s how “Bridge over Troubled Water” is both their monument and their metaphor.

When Simon and Garfunkel were “Tom and Jerry.” (Uploaded to YouTube by Various Artists / Believe SAS)

Paul Simon and Art Garfunkel became friends as sixth graders in 1953, bonding over a mutual love of music. The boys sang in a doo-wop group together and performed as a duo at school events. When they were 15, they paid to record a song at a Manhattan studio; promoter Sid Prosen heard them and signed them to their first deal. Recording as Tom and Jerry, they had a minor hit (“Hey Schoolgirl”) that made #49 on the charts and got them booked on American Bandstand in 1957. They graduated in 1958 and went to different colleges, albeit both in New York City.

Though the two worked solo during their college years, they regrouped in 1963 after Simon’s graduation. Their sound moved into folk, and they played as Kane and Garr. Performing in Greenwich Village, the pair unveiled some new songs, including “The Sound of Silence.” On that fateful night, they were spotted by Tom Wilson, the influential producer who worked with Bob Dylan, Frank Zappa, the Velvet Underground, and more. Wilson got the duo signed to Columbia Records.

The Concert in Central Park performance of “The Sound of Silence.” (Uploaded to YouTube by Simon & Garfunkel)

Like the majority of young acts, their first album didn’t quite catch fire. Garfunkel went back to college, and Simon alternated between music work in England and school in the States, recording his first solo album across the pond. Fate had other things in mind for the duo, though; Boston DJ Dick Summer played “The Sound of Silence,” and suddenly stations along the East Coast picked it up. Wilson, pulling from the sound that he and Dylan had achieved on “Like a Rolling Stone,” remixed “Silence” by adding electric guitar and other elements. When the new version hit stores, it landed in the Hot 100. One million copies later, the song was #1 in January of 1966.

Feelin’ Groovy (Uploaded to YouTube by Simon & Garfunkel)

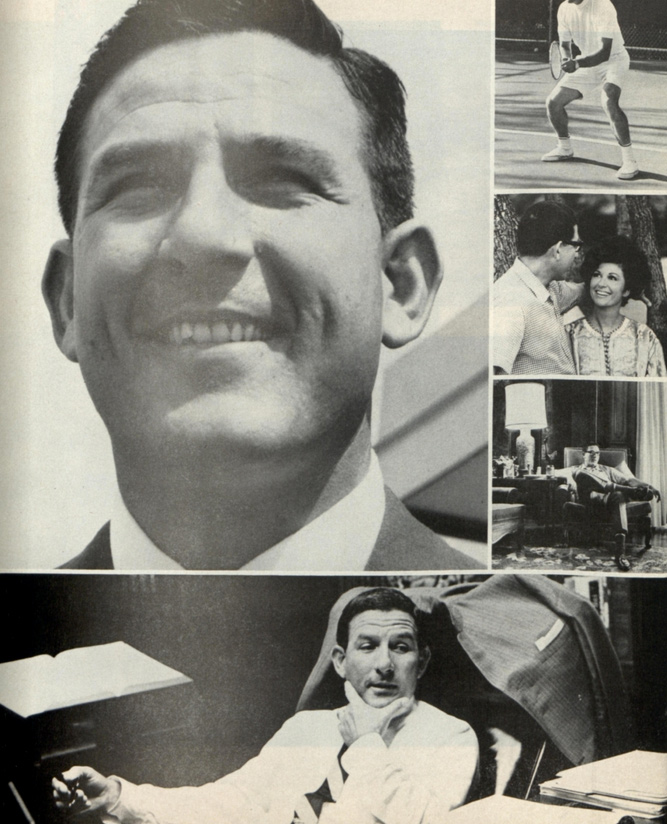

Over the next several years, Simon and Garfunkel became one of the biggest acts in music. Their hastily cobbled together Sounds of Silence album took advantage of the title song’s success and delivered two more songs (“Homeward Bound” and “I Am a Rock”) into the Top Ten. The two new albums, Parsley, Sage, Rosemary, & Thyme and Bookends were outsized hits; the pair’s fame was only magnified by their contributions to the soundtrack to the massively successful film, The Graduate. They were involved as both planners and performers in the storied Monterey Pop Festival, considered by many to be the instigating event in “The Summer of Love.” During this period, The Saturday Evening Post took a deep-dive look at some of the bigger acts in pop music, including Simon and Garfunkel.

Unfortunately, though they helped foster a new atmosphere of love and acceptance, creative and personal tension grew between the pair. Some was born out of Simon’s desire to do solo work, while other pieces came from Garfunkel’s ventures into film, appearing as he did in Catch-22 (and later, Carnal Knowledge, among others). Catch-22’s filming ran long in 1969, which caused more friction.

The pair performing “Bridge over Troubled Water” from The Concert in Central Park (Uploaded to YouTube by Simon & Garfunkel)

When the filming wrapped, Simon and Garfunkel went to work on what would be their final studio album, Bridge over Troubled Water. The 11 tracks were recorded in November of 1969, with the title track getting recorded halfway through the sessions. While there were some mixed critical responses upon its January 1970 release (most focused on a perception of over-production), the public had no such qualms. Bridge took the Grammy for Album of the Year and was the single best-selling album of 1970, 1971, and 1972; for several years, it was the best-selling album of all-time. 50 years ago this week, the title track was in the middle of a six-week run at #1 on the charts, and both “The Boxer” and “Cecilia” were Top Ten singles. “Bridge” is one of the most-covered songs to emerge in the 20th century, with artists like Aretha Franklin, Johnny Cash, and Elvis Presley all recording versions.

Despite the massive success of the album, the pair had already agreed to go their separate ways. Simon had an extremely successful career as a solo act, and Garfunkel worked consistently in both music and film. Over the years, they have reunited on several occasions for special concerts and short tours. The pair even appeared in a Saturday Night Live skit that centered on Simon remembering fans from specific concerts but being unable to recognize Garfunkel. While they have never recorded a studio album since Bridge, the live album The Concert in Central Park, capturing the 1981 live show that they played in front of 500,000 people in New York, sold two million copies. The pair toured extensively in 2003 and 2004, and as recently as 2009, but Garkfunkel’s vocal cord problems derailed the tour; though he recovered within a few years, relations between the two had grown icy again. Simon announced his retirement from touring in 2018, seemingly closing the door on that type of reunion occurring again.

Whether the duo reunites again or not, they’ve left behind a beloved body of work and a reputation for memorable songs with beautiful harmonies. Many critics consider both the single and the album Bridge over Troubled Water to be their defining work. It’s loomed large in popular consciousness for 50 years, and there’s no sign that its sound will ever resemble silence.

Featured image: defotoberg / Shutterstock.com

The Forgotten History of How 1960s Conglomerates Derailed the American Dream

Fifty years ago, you could hardly rent a car, buy a tennis racket, crank up your stereo speakers, or stock up on cans of corned beef hash without putting money into the pockets of James Ling. As the head of Ling-Temco-Vought, the Dallas businessman ran more than 11 corporate subsidiaries that made consumer electronics, packaged meat, and even developed aircraft used in the Vietnam War.

Ling’s conglomerate came into being alongside others, like ITT Corp. and Litton Industries, in the booming years of the 1960s. The low interest rates and simplified stock valuation of the era allowed these giants to take unprecedented hold of diverse industries, and in 1968 this magazine pronounced “It Is Theoretically Possible for the Entire United States to Become One Vast Conglomerate Presided Over by Mr. James L. Ling.” Just two years later, Ling was forced out of LTV, and the capitalist juggernauts of the decade met with an unraveling of the house of cards they had built in quick acquisitions and sketchy stock exchanges.

Ling was a postwar entrepreneur with a decidedly American life story. After his mother died from blood poisoning, Ling’s laborer father sent him to boarding school. He dropped out at age 14 and roamed the country doing odd jobs until he landed an opportunity as a journeyman electrician at an aircraft plant. Twenty-two-year-old Ling left for two years to serve in the Navy and furthered his skills as an electrician while maintaining equipment in the Philippines. Upon his return to Dallas, Ling was intent on transcending hourly wage work, so he sold his house and used the equity to start his own electrical contracting company.

The boldness and tendency for risk that characterized the ex-sailor’s foray into business would remain constant throughout Ling’s expansion. He hustled products and shuffled around finances to make it work for his small firm, garnering an industrial contract that he could barely fulfill. Within a few years, he was looking to go public in spite of an incredulous audience of Dallas business watchers. He hawked his stocks door-to-door and at a booth at the Texas State Fair and scrounged the money together with the help of some faithful investors.

By 1960, Ling-Temco was the 14th-largest industrial company in the country. Ling’s acquisitions over the coming decade dazzled investors as it appeared that he could make a company more profitable and efficient by swallowing it up. His business philosophy was based on the idea of synergy — or, in the ’60s, synergism — the concept that a conglomerate, as a whole, could be worth more than the sum of its parts. “What the sparsely educated Oklahoma poor boy discovered was that two plus two, properly added and managed with flair, can add up to seven or eight if you have enough brains and guts to handle the equation,” Don Schanche wrote of Ling in the Post.

While many American corporations formerly had taken part in vertical integration or horizontal integration (which stirred concern for monopoly), conglomeration in the postwar era — particularly in the ’60s — focused on diversification. Cornell University business historian Louis Hyman says, “It’s the first time that management is valorized as completely independent of the thing being managed. That’s how they justified these kinds of unrelated purchases.” The popularization of the MBA and the veneration of managerial science mystified the clever finances being wrought by conglomerate heads like Ling, who used debt and inflated stock valuation to grow their empires.

LTV’s stock price rose when they took on more subsidiaries, including Okonite, Wilson and Co., and Greatamerica Corp. Ling worked out complicated deals, then split the companies into smaller units, quickly selling the shares for more than the original value of the parent company. He discovered that revenue growth, even without profit growth, could make Ling and his shareholders a lot of money just by reorganizing balance sheets and continuing to acquire.

In Hyman’s recent book, Temp: How American Work, American Business, and the American Dream Became Temporary, he writes, “The real danger of conglomerates was not their power, but how their weakness perverted American corporations and helped to end the postwar prosperity.” Hyman believes the story of Ling’s — and nearly every other major American corporation’s — conglomeration years should be more widely known. Although the overall financial fallout was less acute than in 1929 or 2008, he says the lasting effects of conglomerates on the U.S. economy have been severe.

“My suspicion is that it led to the stagnation of the economy in the ’70s as people focused less on long-term investment and more on the fear of being conglomerated,” Hyman says. “It injected a measure of fear into American corporations.”

Ling’s business practices, under the guise of reflecting management genius, boiled down to a shell game in which longstanding, successful corporations were reorganized to the detriment of innovation and possible value creation. And he wasn’t alone: by the late ’60s, most of the 150 monthly mergers taking place were by conglomerates, which took up more than 90 percent of the Fortune 500. “Most American corporations that survived the 1960s figured out a way to handle conglomeration and deconglomeration,” Hyman says.

The force with which LTV grew led investors to believe it could never fail, and the Federal Trade Commission became concerned.

“The FTC already is worried enough about the growing conglomerate companies in the U.S. to have embarked on a long-term investigation,” Schanche wrote in the Post in 1968. “Ling has branded the probe ‘business McCarthyism’ and a witch hunt.”

The Justice Department filed an antitrust lawsuit against Ling after he acquired Jones and Laughlin Steel in 1968. Investors were troubled, especially since the suit coincided with other losses and a market downturn. The Times wrote, “LTV’s stock, which had traded for as much as $169 a share in 1967, plunged to a low of $4.25 the week Mr. Ling was ousted.” Ling was kicked out in 1970, and the once-gargantuan conglomerate, faced with low market prices, was forced into several divestures in the coming years.

Although the Justice Department’s investigations were timely, the reasoning for LTV’s downfall was in the market. Since Ling’s conglomerate was built on the premise that LTV’s high stock could be traded for the lower stock of his acquisitions, the Dallas man was in trouble (and in debt) when this scheme didn’t deliver.

LTV held on, through several bankruptcies, until 2000, but Ling found it impossible to continue his old ways in a new economy. He went into gas, oil, and real estate, bankrupting some companies and netting profit with others. His glory days were over, for good, and he had to part ways with his $3.2 million Dallas mansion.

In the shadow of the conglomeration years, economists rethought the merits of good management. Harvard economist Michael Porter’s research in the ’70s and ’80s shed doubts on the idea of synergy, and Jack Welch was celebrated for running General Electric more leanly in the ’80s and ’90s. Stock valuation became more detailed as well, focusing on measurable aspects of a company like free cash flow as opposed to accounting abstractions like profit and revenue.

That decade’s lessons of ravenous acquisition were learned perhaps most harshly by LTV and its investors, but their tale of unsustainable growth seems to be renewed with each bubble or boom. History doesn’t repeat itself, but injurious investment banking does.

Myriad opportunities for value and technological growth in the postwar years turned into decades of income stagnation and inequality, largely because of the high-stakes games played by conglomerates. “It’s easy to talk yourself into a deal that makes you and people you know lots of money, but actually harms the company,” Hyman says. In the case of James Ling, clever finances took precedence over production and innovation.

Contrary to the Post’s prediction fifty years ago, the entire United States did not become one vast conglomerate presided over by James Ling. Conversely, the Texan has been largely forgotten by anyone unfamiliar with the annals of American business. His philosophy of rushing for quick money over good economy, however, remains an enduring trope.