Movies for the Rest of Us with Bill Newcott: Hail to the Movie Chiefs

See all Movies for the Rest of Us.

Featured image: Joseph Henabery in The Birth of a Nation

The Centennial of Mickey Rooney, America’s Most Persistent Performer

Today is the centennial of the birth of Mickey Rooney, the once-golden boy of Hollywood with likely the longest-running career of any American (or otherwise) film actor.

After beginning his lifelong stint in show business in a specially-tailored tux in his parents’ vaudeville shows at 15 months old, Rooney landed his first film role at age 6 and didn’t stop until 2014, the year he passed away.

The America of Rooney’s films at the height of his celebrity – when he played the lovably well-intentioned troublemaker Andy Hardy in 16 movies – was The Saturday Evening Post’s America: one with a freshly-ironed moral fabric and joyful endings. In fact, Rooney was a Post boy. As the Post bragged in a short piece in 1942, the actor won a medal at age 13 for selling magazines door-to-door and even at the studios where he made his Mickey McGuire movies: “Andy Hardy, as portrayed by Rooney, more often than not engages in financial enterprises that backfire, but in real life Rooney got away to a fast business start with no adolescent detours.”

The Post’s coverage of Rooney wasn’t always so laudatory, however. By 1962, he was just another example of “moral decay in America” as an editorial shone light on his multiple nasty divorces and thousands in back taxes. “Nothing in this sad story surprises us, Hollywood being the way it is,” the Post printed, “but we remember Andy Hardy.”

The now-familiar arc of the innocent child star becoming a frighteningly flawed adult perhaps began with Rooney’s departure from the saccharine cinema of the Hardy family into the trappings of wealth and fame. But he couldn’t play Andy Hardy forever, and he didn’t want to.

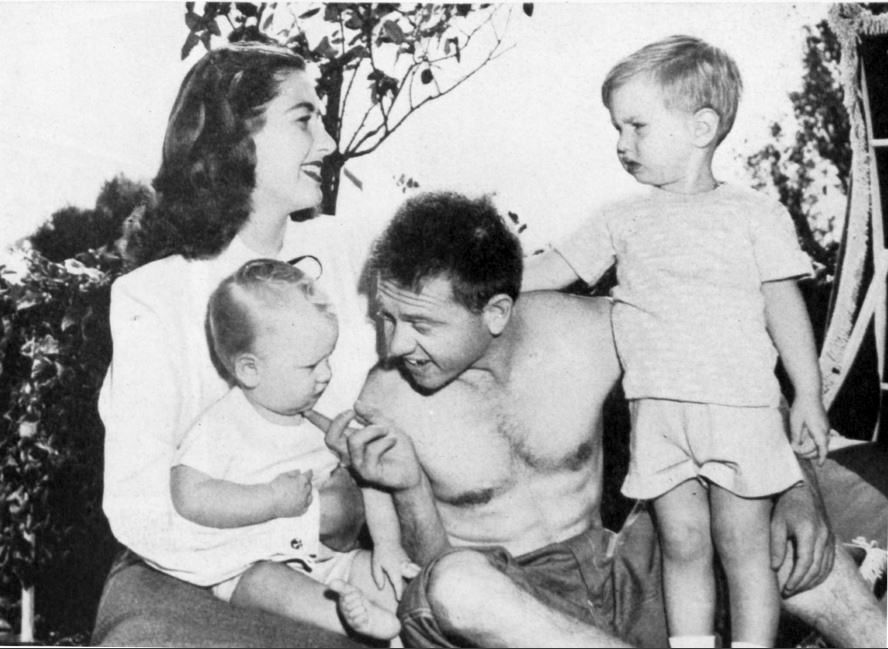

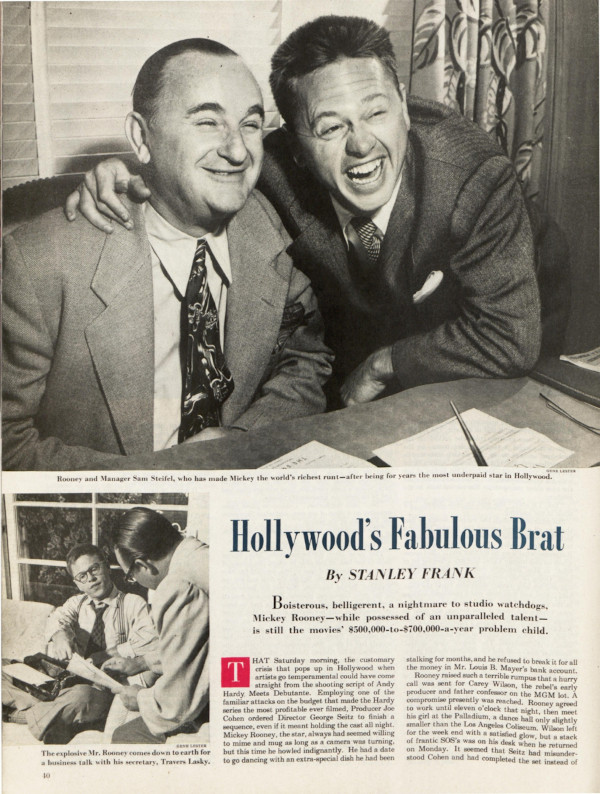

In 1947, the year after Rooney’s last film as Andy Hardy (with the exception of the 1958 revival), the Post published a lengthy profile of the actor called “Hollywood’s Fabulous Brat.” Rooney had spent three years – 1939, ’40, and ’41 – as the biggest box office draw in Hollywood, and he had a reputation for being belligerent, on the set and off. He was also seeking more substantial work.

“I’ll never make another Hardy picture,” he told the Post, incorrectly. “I’m fed up with those dopey, insipid parts. How long can a guy play a jerk kid? I’m 27 years old. I’ve been divorced once and separated from my second wife. I have two boys of my own. I spent almost two years in the Army. It’s time Judge Hardy went out and bought me a double-breasted suit. With long pants.”

Rooney wanted to stretch his wings as he had when he played Puck in Warner Brothers’ A Midsummer Night’s Dream in 1935, when The New York Times reviewed his “remarkable performance” as “one of the major delights of the work.” He wanted to enter into a new chapter of complex films like the forthcoming gritty boxing drama Killer McCoy and the Eugene O’Neill-adapted musical Summer Holiday. After the decades-long run of Hardy family movies and musicals with Judy Garland, however, Rooney’s box office draw dwindled.

Since conquering the motion picture industry with nothing but talent and grit, Rooney couldn’t have foreseen a future where he wasn’t at the top. He imagined he could reinvent his career with the same momentum he always had. As Nancy Jo Sales wrote in Vanity Fair after Rooney died in 2014, “his career suffered from his juvenile appearance, and his diminutive height — he wasn’t a boy anymore, and he wasn’t a leading man, so where did he fit in? — but he never gave up.” Rooney kept making films into the 21st century, delivering memorable performances in movies like The Black Stallion and It’s a Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad World. In 1979, he took on Broadway in the successful revue Sugar Babies, spawning years of tours.

Rooney’s undeniable talent steered him toward a lifelong commitment to entertainment. Given his start in the demanding realms of vaudeville and the old Hollywood studio system, the performer never hesitated to master new skills, like banjo-playing or crying on demand, to satisfy his audience. This was perhaps never more true than in 1941, when Rooney performed at President Roosevelt’s Inauguration Gala.

Alongside talents like Charlie Chaplin, Ethel Barrymore, and Irving Berlin, Rooney was expected to contribute an act of celebrity impersonations. He had a better idea: he would play his three-movement symphony Melodante on piano instead. As the Post reported, “The audience of 3,844 celebrities laughed when Rooney sat down at the piano that evening and shot his cuffs as he poised his hands over the keyboard.” They thought he was doing a bit. After he played the 19-minute score he had written himself, however, they burst into applause.

For Rooney, the label “triple threat” was an understatement. Starting from a poor broken home, he gave everything he had to build his iconic career, but it never turned out exactly the way he wanted. “People look at me and say, ‘There’s a lucky bum who got all the breaks,’” he said in 1947, “Yeah, I got the breaks — all in the neck.”

Featured image: Gene Lester, The Saturday Evening Post, December 6, 1947

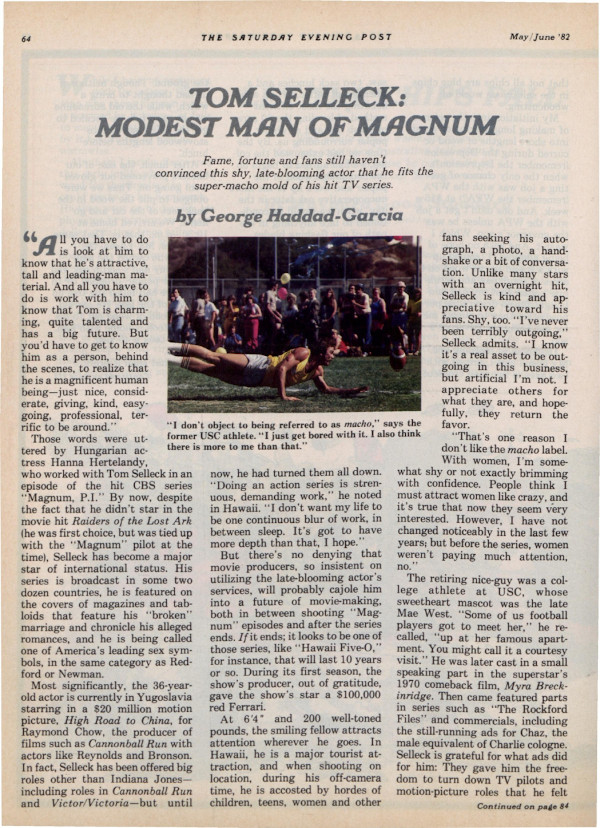

Tom Selleck Riffs on Fame

—From “Tom Selleck: Modest Man of Magnum” by George Haddad-Garcia, originally published in the May 1982 issue of The Saturday Evening Post

“I think my biggest problem has always been being taken seriously. I walk into a casting office and I’m tall, and I imagine they say to themselves, “Who is this big, dumb guy? What’s he trying to do, get by on his appearance?” And lots of people resent it — but they should be resenting Mother Nature.” …

“I’ve never been terribly outgoing. I know it’s a real asset to be outgoing in this business, but artificial I’m not. That’s one reason I don’t like the macho label.” …

“People think I must attract women like crazy, and it’s true that now they seem very interested. However, I have not changed noticeably in the last few years; but before the series, women weren’t paying much attention, no.” …

“I’m still the same guy who did television commercials for Pepsi Cola at $250 a shot.”

This article is featured in the September/October 2020 issue of The Saturday Evening Post. Subscribe to the magazine for more art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

Featured image: Courtesy CBS

50 Years Ago, Flip Wilson Changed the Face of TV Comedy

Flip Wilson started working his way up the comedy ranks in the 1950s, but his big break came in 1965. That’s when Red Foxx told Johnny Carson on The Tonight Show that Wilson was the funniest comedian out there. Carson put him on, and stardom followed. Within five short years, Wilson was at the helm of his own variety and sketch-comedy show, The Flip Wilson Show. The trailblazing series saw Wilson become one of the most visible and popular Black entertainers in America. On the 50th anniversary of its first episode, here’s a look back at Wilson’s journey and how his show became a platform that propelled other artists forward.

Clerow Wilson Jr. was born in 1933. His mother left his father, him, and his nine siblings when he was seven; as a result, Wilson and a number of his siblings went to foster homes. Wilson joined the Air Force when he was 16 (yes, he lied about his age). Wilson’s natural instincts for entertaining emerged, and his gift for comedy soon saw him sent from base to base to improve morale. Some of his fellow servicemen would describe him as “flipped out” and called him Flip. Wilson would adopt that name and perform under it for the rest of his career.

Flip Wilson on The Ed Sullivan Show from 1970 (Uploaded to YouTube by The Ed Sullivan Show)

After the Air Force and into the early 1960s, Wilson built his comedy brand. He recorded a pair of albums, Flippin’ (1961) and Flip Wilson’s Pot Luck (1964) during this period as he performed in clubs. He also appeared regularly at the Apollo Theater. When Redd Foxx endorsed him to Johnny Carson, it facilitated his entrance onto television. In addition to multiple appearances on The Tonight Show, Wilson would appear on The Ed Sullivan Show, The Dean Martin Show, Here’s Lucy, and more. With the launch of Rowan and Martin’s Laugh-In in 1968, Wilson was billed as a “Regular Guest Performer” through the first four seasons.

Wilson’s growing popularity earned him a shot with his own show. The Flip Wilson Show debuted on September 17, 1970, on NBC. The program incorporated sketches along with music and celebrity guests. Wilson played a variety of recurring characters. Easily the most famous was Geraldine Jones, his take on a modern Black woman from the South. Geraldine turned out to be something of a catchphrase machine, with lines like “The Devil made me do it,” “What you see is what you get,” and “When you’re hot, you’re hot; when you’re not, you’re not” entering the cultural vocabulary.

Flip Wilson on The Midnight Special (Uploaded to YouTube by Midnight Special)

Wilson used the show as a platform for a number of other Black performers. The show included early appearances by the Jackson 5 and welcomed stalwarts like Aretha Franklin, The Temptations, The Supremes, Stevie Wonder, Ray Charles, and more. He also brought on a wide range of other guests, featuring everyone from Johnny Cash to Bing Crosby to Joan Rivers. Musical guests also frequently took part in the comedy bits. Among Wilson’s writers was legendary comic George Carlin, who himself was in the midst of a turn toward more countercultural comedy; Carlin occasionally appeared on the show as well.

In a short period of time, The Flip Wilson Show was one of the most watched programs in America, falling behind only All in the Family in 1971. It was a groundbreaking success, as Wilson became one of the few Black entertainers to be that popular with white audiences as well. The show was also recognized for its overall quality; it won two of eleven Emmy nominations and earned a Golden Globe for Wilson for Best Actor in a Television Series. Wilson’s fame grew, but the network began to resist his demands for a larger salary. As the show went on, ratings dipped (as they did for most prime-time variety shows of the period), and the series was cancelled in 1974.

Eddie Murphy and Jerry Seinfeld discuss the greatness of Flip Wilson and other comics (Uploaded to YouTube by Netflix Is A Joke)

Wilson worked regularly in comedy, television, and film over the following years. In 1983, he memorably hosted Saturday Night Live; he even played Geraldine in a sketch that “revealed” her to be the mother of Eddie Murphy’s hairdresser character, Dion. Wilson headlined the TV show People Are Funny in 1984 and was the lead in Charlie and Co. from 1985 to 1986. His last television appearance was on a 1996 episode of The Drew Carey Show. Wilson passed away from liver cancer in 1998 at the age of 64.

Wilson reached all audiences with his humor and put acts in front of audiences that might not have seen them otherwise. His influence extended into the way Americans talk; even the editing software WYSIWYG is an acronym taken from one of Geraldine’s catchphrases. He earned the admiration of comedians like Redd Foxx and Richard Pryor, worked to get the best facilities for his show, and wasn’t afraid to demand compensation commensurate with running and starring in the #2 show on television. If what we saw was what we got, then we got greatness.

Featured image: Flip Wilson as Geraldine Jones interviews Dr. David Reuben on an episode of The Flip Wilson Show (Wikimedia Commons)

An Interview with James Brolin

James Brolin has won generations of fans since he first became a hit co-starring in Marcus Welby, M.D. His sense of humor and down-to-earth perspective on show business is front and center when he remembers with a laugh, “They gave me an Emmy and a Golden Globe for that role. There were tears just running down my cheeks in a scene where I was reading an emotional letter. I should have thanked salt water and menthol for helping me cry.”

Brolin’s imposing 6-foot-4-inch stature and craggy profile helped make him a star in a string of TV series and movies, from Hotel to Westworld, from Amityville Horror to Traffic. He reveals his biggest challenges were playing two real-life legends, Clark Gable in Gable and Lombard and Ronald Reagan in The Reagans.

He was delighted to score again in a juicy supporting role in four seasons of the popular CBS series Life in Pieces as Pop-Pop. “I loved that it was so real in dealing with family relationships,” Brolin says. “I didn’t know how much fun I’d have with a great cast.”

Next up for the 79-year-old is Sweet Tooth, Robert Downey Jr.’s new series based on the DC comic. Lots of young comic fans have already shared their enthusiasm for Brolin as the narrator. And at the top of his wish list is directing a movie based on the true story of Ruby McCollum, a wealthy African American who was convicted of killing a prominent Florida state senator in 1952.

Brolin is proud of the wide collection of characters he’s played, but he still jokes, “I’m Barbra Streisand’s husband and Josh Brolin’s father. Those are my important credits!”

Jeanne Wolf: Do you still have the same enthusiasm for acting after such a long, distinguished career?

James Brolin: My kids figured out that I’ve spent about 9,500 days on film and TV sets. I’ve been in heaven every one of those days. Every minute you put in makes you better than when you started. For me, the tough part was often what it takes to get ready. I was a shy guy when I was young, and that would come back in mental blocks. When I felt truly up the creek, I’d drive from L.A. to Bakersfield with a script and keep reading it aloud along the way. It’s a four-hour trip and I would go into a sort of alpha state, but by the time I got back, I knew every line.

Then there were times when I had doubts and fears about playing larger-than-life characters, like Clark Gable in Gable and Lombard and Ronald Reagan in The Reagans, even though the directors really wanted me. I had to be convinced. After a lot of hard work, I saw that they were right.

I kept saying I wasn’t right to play Gable in Gable and Lombard. And Sidney Furie, the director, kept saying, “You can do this. I’m putting you in the screening room and you’re watching Gable movies for two weeks. And so I did, and that changed everything in my mind. Sidney was right.

When I did the president, I’d be walking around my hotel room at three in the morning holding my computer watching clips of him and thinking, “I’m not this man. How do I become him?”

I also had my doubts about taking a supporting role in Life in Pieces, and it ended up being four rewarding years. I think I put a little of my own dad into that character, which is funny because when I said I wanted to be an actor, he went, “I’ve got a 10,000-to-1 bet against you.” Then, after I became successful and changed my last name from Brudelin, he made reservations using Brolin. Suddenly, he was Henry Brolin.

Actually, playing all those roles hasn’t been just for me. I’m trying to get butts into theater seats to really have fun for a couple of hours. You’ve got to keep the audience in mind whether you’re acting or directing. You can’t leave them bored. I feel that we’ve seen so many movies and TV shows go by that wowing people is tougher than ever. A film ends up like day-old bread from the bakery, worth half the price. You kind of have to go, “Okay, what’s next? What can I do better than I did before?” At my age, I have to swallow this pill of, “Will I ever work again and will it be worthwhile?” But I love being on the set. Making a movie brings together people who are the best enablers, so full of ideas and wanting to please. When I was directing, I’d give them a challenge and wonder how they pulled it off. They’d say, “I just gave you 30 percent more than you paid me for.” They don’t know any other way.

JW: You have many talents and things you love. Is that your personal secret to youth?

JB: As a teenager, up until I was 18, I would go to the UCLA library and wander through different sections. I didn’t love school, but I loved to explore things. I’d think, “Oh, photography, that sounds interesting.” I’d find a book and start reading it. And then I would just get bored, and go, “Okay, enough of that.” And I’d go to another section. Sometimes, I would be there all day and maybe delve into five different subjects. I could learn more in the library than sitting in classes.

I feel like I’m in a hurry now because there’s so much to learn. And there’s travel, not that we’re going anywhere during the pandemic, but there’s so much yet to see. You go to Google and type a city, like Tonga, in middle of the Pacific. And you go, “Man I want to go there,” but there’s no time.

It’s funny. A lot of people sat around at home during the pandemic wondering what to do. I feel like I don’t have time to do everything, and going to work would be a vacation. Right now, I’m studying to get my commercial pilot’s license. My dad was an engineer who worked on the Douglas DC-3, but he was never a pilot himself. I took my first flight at 18 and was hooked. I’ve been flying for 50 years.

And I’ve always loved cars. I just got a new Porsche, but basically I drive a Mini Cooper and, of course, my Raptor truck with the big tires. That’s the cowboy side of me.

And I’ve just bought a lot overlooking Malibu Lake that tilts at a 45-degree angle. They say you can’t build on it, but I’m going to put up a sweet little house there. And I’m doing workouts with the big wave surfer, Laird Hamilton. He puts me underwater in my pool with a 20-pound weight in each hand, and I have to get to the surface before I run out of air. I’m in the best shape ever. So life is good, and you’re invited to my 100th birthday, whenever that it is.

JW: You’ve been married to Barbra Streisand for over 20 years. What’s your secret?

JB: We really do have a wonderful time. We certainly are very different from each other, but being at home so long during the quarantine was proof of how happy we are to be together. I’ll tell you, things are never dull, and after we each do our thing all day, we are just glad to see each other. That doesn’t mean we don’t pick at each other like people do, but we have an instant laugh about it. Or you go off in the corner, and when you come back, pretend like nothing was ever wrong in the first place.

After practicing in two other marriages, I got it down pretty good. Barbra corrects me and I push her, but she backs me up in all of my passions, from flying to directing. I appreciate the extraordinary things she’s done, but people would be surprised at how simple the things we love are. When you decide that this is a lifetime deal, you think of ways to make each other’s life better. You don’t expect everything to be perfect, but it’s perfect because you trust each other and you are there.

JW: What’s in the future for you and your family?

JB: Barbra really believes in leaving a legacy, so she’s been tied up writing a book about her life and career. There have been a lot of false stories about her, and she’s setting the record straight. She’s a truthmonger.

But I’m easy, and my mother was easy. When I decided I wanted to become an actor, Mom said, “Whatever you want to do, just go for it. I’m with you.” You’ve got to roll with the punches a little bit. Give people a little room. If you get a dog from the pound and he bites you, give him a little food and a little love, and don’t forget that someday he might still bite you again.

I don’t know how I’ll be remembered. Maybe as Josh Brolin’s dad. I watched him through all his ups and downs. As a father I was there to catch him if he fell. In the meantime, I couldn’t advise him. If I insisted on anything as Josh was growing up, he would either disappear or just be totally angry. It didn’t work like it does in a movie. During the pandemic, he’s been Mister Dad, staying at home and changing diapers, but he’ll soon be busy again. We’re all just proud and waving at him as he passes by.

This is the full version of an interview that ran in the September/October 2020 issue of The Saturday Evening Post. Subscribe to the magazine for more art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

Featured image: Photo by Gilles Toucas

Movies for the Rest of Us with Bill Newcott: Peter Sellers’ Best Movie Moments

See all Movies for the Rest of Us.

Featured image: The Ghost of Peter Sellers (1091 Media)

3 Questions for Michael Caine

For The Saturday Evening Post, I’ve talked to the biggest and the best — the world’s most interesting, influential, and talented famous faces. I’m always asked about favorites. Right at the top of that list is Michael Caine. The best storyteller: He can mesmerize a table of A-listers like nobody else. A spectacular actor: Caine brings charisma and truth to a character with a mastery that only a few screen stars possess. Fans across generations adore him, yet this legend has a relationship with fame that is straightforward and down to earth. In his books and in person, he shares a sly wisdom that always leaves me laughing and thinking.

At 87, he’s still ready to step in front of the camera to play parts he can’t resist. You’ll see him in the upcoming Tenet, an action epic with a twist of time traveling from Christopher Nolan, who considers Michael a good luck charm as well as acting genius, and Best Sellers, a bittersweet comedy about an cranky, aging author. I’ve often asked Michael, with all that’s come his way, how much does he credit hard work and how much does he bow to good fortune? He says, “I gave God a hand.”

Jeanne Wolf: You seem to slip so effortlessly into every character you play but I know how very serious you are about your work. Does the intense dedication pay off as you hide the effort?

Michael Caine: If you’re watching me in a movie and you say to your companion, “Isn’t Michael Caine a wonderful actor,” then I’ve failed. You shouldn’t be noticing the acting. You should be wondering what’s gonna happen to the guy I’m playing. The art is to make yourself disappear.

There are actors who hold up a mirror and say, “Look at me.” I hold up a mirror and say, “Look at you!” My acting should be so human that you say, ”How did he know that about me?” What you should get from my performance, to quote Edmond Wilson, is a “shock of recognition.” I want people to see me on the screen me and say, “I am him.” They know if they met me in the street, I’d talk to them. I wouldn’t be in a limousine flashing by with two blondes and a bottle of champagne. Although, mind you, that’s not a bad idea.

When actors are nervous, it can screw up a scene because it will make the audience feel uncomfortable. I’m often kidding and joking right up to the minute when they call “action.” With me you feel comfortable because I make it look like it’s a walk in the park. But that can be a double-edged sword. It’s like watching Fred Astaire dance. People may think, It’s a breeze. I could do that. Believe me, it isn’t as easy as it looks. It’s like a sort of drug in a way. It’s getting it absolutely right and knowing you’ve done it and you couldn’t do it any better. Sometimes I say to the director, “If you want it any better, you’re gonna have to get someone else cause I can’t do it better than this.” And if you get to that stage, you know, it’s great.

JW: You’ve written a book about acting, yet you’ve said that watching films and doing films was your own best teacher. So what do you tell your young co-stars about what you’ve learned?

MC: I always used to ask old successful actors for advice. Every single one of them said, “Give up acting.” So I say to young actors, “Don’t ask me for advice. The worst thing is it’s free. If you had to pay for it, it might be worth something.”

Early on I took everything because I had no money and I came from a very poor family. Once I started making movies, I thought no one was going to offer me another one so I always took the next one. Finally, I realized I could stop that. From then on, the mistakes I made in choosing roles were genuine mistakes. I thought it would be a good movie and it wasn’t. That was that. But then you get to another period where you don’t have to work. I only do things that I absolutely cannot refuse. I could not refuse Phillip Noyce offering me The Quiet American. I couldn’t refuse being Austin Powers’s father, or Sandy Bullock’s beauty mentor, and, of course, the butler in Batman. One thing now is I don’t get the girl, I get the part. When I used to get the girl, she’d be the most beautiful. Now I get the most beautiful part.

JW: You have a wonderful marriage. You and Shakira Baksh have great joy together. Has experience taught you how to savor your rich personal life?

MC: I live life to the fullest every day. I believe in that. That’s my basic philosophy. Because this is not a rehearsal. This is the show. We’re not opening next Thursday; this is it, we open today. However old you are I think you have to make the most of your life. And I do. There isn’t a day passed where I don’t try to do something. They nearly retired me once, but I came back.

I have this photograph on my sideboard in my dining room. There are three achievements. There’s one of my holding an Oscar. There’s one of the Queen knighting me with the sword actually touching my shoulder. The other is me standing at the top of Sydney Bridge in Australia after an arduous climb.

I wasn’t a success until very late in life. I never made my first big proper movie until I was 29. I was already set in a very concrete way into the person I was going to be, so nothing ever fazed me. Maybe it started with my mother. My father, who was my role model, went away to the war in 1939. I was six. My mother didn’t say, “Oh, now I have to look after you on my own.” She said, “Now Michael, you have to look after me.” So she made a small man of me. I became my father, which stayed with me for the rest of my life. Looking back, I always figure that I’ve been very, very lucky, and I’m just in awe of how lucky I have been — not what I’ve done. That’s why I don’t gamble. I haven’t got any luck left.

This is the full version of an interview that ran in the July/August 2020 issue of The Saturday Evening Post. Subscribe to the magazine for more art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

Featured image: Denis Makarenko / Shutterstock.com

3 Questions with Patricia Heaton

Patricia Heaton has relived moments from her own life as a mother playing a TV mom on the hugely popular sitcoms Everybody Loves Raymond and The Middle. Now the Emmy and SAG Award winner is imitating aspects of her life again in the CBS comedy Carol’s Second Act. Dressed in scrubs, she’s is an empty nester pursuing her dream of becoming a doctor. “My own four sons are pretty much out of the house,” she says, “and I was wondering what might come next. So it’s been interesting to have this experience with Carol who’s working with interns who are half her age.”

Taking on a new role in her TV career made Heaton realize the potential in all of us to find ways to change direction. That led her to write Your Second Act: Inspiring Stories of Reinvention, due in bookstores in May. “I found stories of some really fascinating people who’ve reinvented their own new lives,” she says. “I think that the book will encourage and inspire a lot of people.”

Jeanne Wolf: Why are second acts so important?

Patricia Heaton: For people whose kids have left home or maybe they’ve retired, it can be a challenge to adjust to a new way of living. I want to encourage them to look inside themselves and to see where they’d like to be in the world at this stage. The world needs all of us. As for me, I’m in Oklahoma producing my first movie. Finding so many things to learn. It’s crazy. And, very important, for a couple of years now, I’ve been a celebrity ambassador for World Vision, which provides relief and aid to children and their families in nearly 100 countries.

JW: Does your sense of humor and having built a career on being funny on television help you cope with whatever life brings you?

“Most real comedy comes from pain. You try to find humor in the troubling situations.”

PH: I think especially in the darkest part and the most difficult times, you just must see the humor and the irony in crazy things that happen. Most real comedy comes from pain. You try to find humor in the troubling situations.

JW: Do you ever think, “I can’t believe the life I’ve led as the star of those iconic TV comedies?”

PH: Every single day I feel that way. I tried to make it in New York for nine years, and I couldn’t get arrested. It’s shocking to me even now that when I came to Los Angeles I didn’t have a car or an agent or a manager. It’s miraculous that I’m sitting there today, having done all the things I’ve done.

Even with success, I think my own ego was getting in the way. I finally realized I needed to step aside and let a greater power take control. I realized I needed to be pursuing it because it’s what God intended for me to do on this planet. And once that dawned on me, I kind of let go and said, “Okay, you lead me,” and things started falling into place.

Of course, an actor never wants to stop acting. It all started when I was in second grade, seven years before I lost my mom to a brain aneurysm. I told Sister Delrina I could sing the entire Color Me Barbra album, and I did for my class. But I know the truly important things in life are your family and friends. I think about what people will say at my funeral. Will it be that you had fabulous ratings and won some big awards? Or that you were a good and kind person. I hope it’s the latter.

This is the full version of an interview that ran in the May/June 2020 issue of The Saturday Evening Post. Subscribe to the magazine for more art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

Featured image: Joe Seer / Shutterstock.com

3 Questions with Patrick Stewart

Patrick Stewart looks absolutely splendid. He smiles at the compliment. “It’s a tribute to my peasant genes.” Stewart admits that being a self-declared workaholic is part of the secret to seeming more than a little like the Captain Jean-Luc Picard from 25 years ago. Now, he’s bringing him back for CBS All Access on Star Trek: Picard in a startlingly new take on the futuristic world.

Stewart made his debut in a school play at six and has never stopped working, on screens big and small as well in theaters around the world. At 79, he can look back on a career in which he’s played nearly every Shakespearean legend and a stunning array of memorable characters in too many movie and TV shows to count, but Sir Patrick is probably most proud of being knighted by the Queen. Stewart reveals that the biggest challenge he faced in his new venture was making sure that Star Trek moved into a future which reflects changes even Gene Roddenberry hadn’t imagined.

Jeanne Wolf: You had some very strong opinions about what you wanted Star Trek fans to see before you took on the challenge of a new series, didn’t you?

Patrick Stewart: I wanted diversity. Many years have passed since the last time I was on a Star Trek set. The world is a different place. So we find our beloved Picard in a life which bears no resemblance whatsoever to his service as a Starfleet captain.

“There’s always an improvement that can be made for humankind and society.”

As for taking on a new challenge, I have never thought of retirement. Sigmund Freud said, “The two most important things in a life if you want to be happy are love and work.” I am very blessed that I have the former, perhaps in ways I’d never have anticipated. However, the work has always been a bit more negative because I’m obsessive. People have said to me, “The problem with you is that you only know how to work, and when you’re not, you don’t feel as though you’re Patrick Stewart at all.” In a sense, that is true. With acting, when I first dipped my toe into that particular creative pool, I was delighted to discover that I could spend a lot of time not being Patrick Stewart, which gave me a great deal of satisfaction.

I sometimes look back and think, How did this all come about? All I wanted to do was be on stage reciting Shakespeare and nothing else, and then suddenly I find that I had become somebody that I still don’t quite know how to be.

JW: What has shaped you both personally and as an actor?

PS: I didn’t have an idyllic childhood, although I started doing some acting at a very young age. My education was over at 15. In the society that I grew up in, you went to work after that. It was usually in a factory, mill, or coal mine. That was where most of my family, after primary school, ended up — and quite a few of them went to prison as well. I was blessed to have one significant person standing at my side, my English teacher, Cecil Dormand. He’s 96 and still doing great. We still have wonderful conversations, and he talks to me like I’m 15 sometimes. Cecil was the one who encouraged me and pushed me in the right direction. We all need someone like that.

And I inherited something from my father. Actually he was an incredible man — a soldier, the most senior noncommissioned officer of the parachute regiment. There was always optimism in the things he expressed. That’s why I felt so connected to Jean-Luc Picard, because he always looked for a better way and improvements that could be made. I’ll never forget one fan letter I got from a police officer who said he loved his job but there were days when he came home stressed and depressed, feeling there was no future at all for any of us. That’s when he’d get out a DVD of Next Generation and watch it and be assured that he was wrong. There was a better world waiting for us. There’s always an improvement that can be made for humankind and society. That, I still passionately believe in, I just think it’s going to be a very difficult few years until we get to that place again.

JW: After some years together, you married singer and songwriter Sunny Ozell. What about love and marriage; has that become simpler even though she’s half your age?

PS: Yes. In the sense that I now think I understand the importance and significance of sharing life with one other person in particular. It’s a glorious gift. The communication between two people from massively different backgrounds like my wife and I brings out in me a reassurance and happiness that, quite frankly, I never thought I would experience. So much joy. Fun doesn’t begin to describe it. Joy would be closer to the experience.

—Jeanne Wolf is the Post’s West Coast editor

This is an expanded version of an interview that appears in the March/April 2020 issue of The Saturday Evening Post. Subscribe to the magazine for more art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

Featured image: Shutterstock

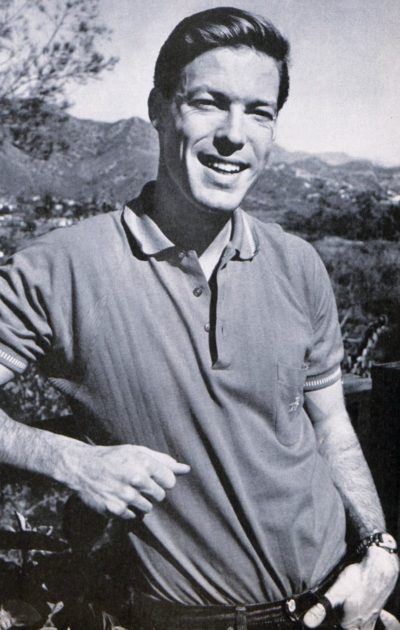

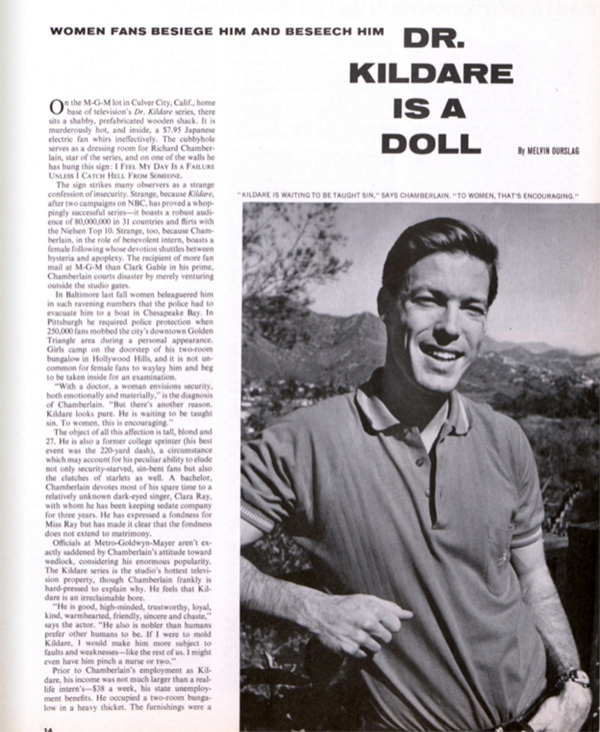

Dr. Kildare Is a Doll

Originally published in The Saturday Evening Post March 30, 1963

The recipient of more fan mail at MGM than Clark Gable in his prime, Richard Chamberlain courts disaster by merely venturing outside the studio gates. In Baltimore last fall, women beleaguered him in such ravening numbers that the police had to evacuate him to a boat in Chesapeake Bay. In Pittsburgh he required police protection when 250,000 fans mobbed the city’s downtown area during a personal appearance. Girls camp on the doorstep of his two-room bungalow in Hollywood Hills, and it is not uncommon for female fans to waylay him and beg to be taken inside for an examination.

“With a doctor, a woman envisions security, both emotionally and materially,” is the diagnosis of Chamberlain. “But there’s another reason. Kildare looks pure. He is waiting to be taught sin. To women, this is encouraging.”

The Kildare series is the studio’s hottest television property, though Chamberlain frankly is hard-pressed to explain why. He feels that Kildare is an irreclaimable bore.

In the 3,500 letters a week he receives, women open their hearts to him, some discussing intimate medical problems. “You would think this is mail-order gynecology,” says Chamberlain. “My answering service adheres to the ethics of medicine by offering no advice.”

Last September the studio decided to expose Chamberlain to his public for the first time, hardly suspecting the dangers. There followed the riot scenes in Baltimore and Pittsburgh. Then he was shipped off to New York, where one day he decided on a quiet stroll through the Central Park Zoo, hoping to go unnoticed in blue jeans, sneakers, and T-shirt. The attire didn’t fool a teenage girl. She screamed. Soon she was joined by a small squealing mob. One girl slipped her class ring on his finger. Others threw scarves at him. Another, undeterred by the trumpeting elephants nearby, rested her head on his back and moaned rapturously, “Oh, doctor.”

—“Doctor Kildare Is a Doll” by Melvin Durslag, March 30, 1963

This article is featured in the January/February 2020 issue of The Saturday Evening Post. Subscribe to the magazine for more art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

Featured image: Collection Christophel / Alamy Stock Photo

3 Questions with Alan Alda

Alan Alda isn’t exactly resting on his laurels, or resting at all for that matter. He received the coveted Screen Actors Guild Lifetime Achievement Award last year, to add to his seven Emmys, six Golden Globes, and an Oscar nomination for Best Actor in a Supporting Role for Martin Scorsese’s The Aviator. Of course, none of those overshadow his rise to stardom as “Hawkeye” Pierce in the ever-popular, darkly comic ’70s TV series M*A*S*H. He’s currently playing a lawyer in Noah Baumbach’s scorching Marriage Story, now streaming on Netflix, alongside Scarlett Johansson and Adam Driver.

The star has been out front in the battle to find a cure for Parkinson’s disease. He explains, “When I first knew I had Parkinson’s, I waited a couple of years to reveal it. I finally went public because I wanted to help remove the stigma. People who don’t want to admit they have it are holding back the progress we can make to cure the disease. If you get Parkinson’s, your life is not over.”

Jeanne Wolf: You play the voice of logic and kindness in Marriage Story as an attorney acting reasonable in the unreasonable atmosphere of a breakup.

Alan Alda: I didn’t need to do any research to play a lawyer. I’ve been through a lot of lawsuits. I love a good lawsuit. I’ve sued a few of the film studios (but I’m not saying what for). I think some of them thought I was too polite and wouldn’t take them on. You know I’ve always had that nice guy image, but that’s a bum rap. I get angry like everybody else.

JW: Your father, Robert Alda, was an actor. Did he want you to follow in his footsteps?

AA: My father encouraged me by discouraging me. He said, “No, don’t be an actor, it’s a hard life,” and then he tried to get me jobs. I guess I sort of paid him back by getting him parts in several episodes of M*A*S*H. That was fun. The only advice my dad gave me about acting that I can remember is, “Your legs will get tired, so always find a place to sit down.” It’s true. If you watch me on M*A*S*H, you’ll see how often I was sitting down with my feet up on the desk.

JW: I love that you’re working as hard as ever. What keeps you going?

AA: Number one, it has to sound like fun, and it has to seem like it will be a challenge because I don’t want to keep doing what I’ve done before. It’s like walking a high wire between two buildings and seeing if you can keep from falling off. It doesn’t always have to be in front of a lot of people. I’ve gotten as much of a kick out of performing in a small theater before a couple of hundred people as 20 million on TV or in a movie.

—Jeanne Wolf is the Post’s West Coast editor

This article is featured in the January/February 2020 issue of The Saturday Evening Post. Subscribe to the magazine for more art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

Featured image: Shutterstock.com

3 Questions for Danny DeVito

After almost five decades in show business, Danny DeVito still gets a kick out of seeing himself on a movie poster. For the new live-action Dumbo, directed by Tim Burton, he’s sporting a top hat as the ringmaster of the circus that is home to the famous flying elephant. “I’m very at home in the center ring,” he laughs. “The part felt familiar because when I did Batman Returns with Tim I had a circus troupe.”

The Oscar nominee and Golden Globe winner has taken on roles of ordinary and extraordinary characters like no one else on screens big and small. He’s loveable even when what he does and says should make us cringe. Imagine encountering Taxi’s Louie De Palma in real life — especially in our politically correct environment. And then there’s Frank on It’s Always Sunny in Philadelphia: crude, rude, and funny as hell.

Now DeVito is working with Dwayne Johnson on the new Jumanji, and The Rock couldn’t help but gush about his newly minted co-star, saying, “The idea of Danny DeVito joining our cast was too irresistible.”

Jeanne Wolf: I just saw you on Michael Douglas series The Kominsky Method. Do you still go after the best parts, or do they come to you?

Danny DeVito: Both. But actors want to work. Maybe some are thinking about becoming big movie stars, but I always believed the best thing for me was to focus every day on trying to get a job. Moment to moment, you think to yourself maybe you’ll get lucky. Of course, for me, the big break was getting Louie de Palma in Taxi. You don’t know when it’s going to come, so you just want to be ready. What you live for as an actor is to get up there and be with other actors. Now I have the best gig in the world doing It’s Always Sunny in Philadelphia, which has been around a lot longer than Taxi. But every day I still call my agent and say four words: “Get me a job!”

But acting is not just a job, it’s a craft. My grandfather was a tailor. He could take a piece of cloth and make the most beautiful things. I like to think I’ve got some of that ability to take all the elements and work them into something beautiful, something that will grab people and entertain them. Also, I’ve gotten rid of my worst impulses by acting them out. It started with Louie. It’s like a license to kill. I was given this wonderfully diabolical, self-serving, self-centered character to play.

JW: Did you dare to dream as big as the films and TV shows that have made you a big star?

DD: When I was a kid I used to sit in front of the TV watching old movies and thinking I could do that but I couldn’t really tell my pals what I was planning. That would have been too tough. They would have said, “Danny what’re ya, nuts? Who d’ya think you are, Cary Grant?” So I had to keep my mouth shut. But I was learning about comedy.

My mother and father had what I guess you could call an explosive relationship. Everybody was always saying exactly what was on their mind. Sometimes, being funny was the best way to hold your own, and that can really develop your sense of humor. Now, I’ll do almost anything for a laugh. I don’t want to do any kind of dangerous stunts because I’m a chicken, but I will do anything if it is funny for the script. I’ve gotten thrown out of windows. I’ve been naked. I’ve puffed myself up in a fat suit with makeup. I’ve done everything.

JW: We’re in the middle of an immigrant controversy. Your family were immigrants.

DD: My grandparents came from southern Italy. They lived in cold-water flats in Brooklyn. My grandfather shined shoes. He didn’t have a skill. So it’s like a normal story for immigrants — coming here and not speaking English. They came because they had no money, not unlike the cases of the people from Nicaragua and from El Salvador who are coming to the border. And here we are in this big, beautiful country that has all these legends, like the Statue of Liberty, and it has all this land and is so wealthy. I would come here too. I would do whatever I could to try and get into the country.

But you can’t live in the past. What you gotta do is think of the future because what you’re doing right now is gonna be the good old days. If you sit around on your butt and don’t do anything, when you’re 90 you’re going to have no “good old days” to think about. You’ve got to do it now. You gotta get up and do something. Don’t sit around just listening to all the claptrap on television. Go out to the movies because going out to the movies is an experience in itself. Take a friend, go out to dinner. Don’t drink and drive, but have a good time.

Entertainment, that’s what we do. We are a release. You go into the movies and the lights go down and you become absorbed in the story. It’s like reading a good novel. It takes us from our reality and shows us, in our lives, something that we can hang our hat on and emulate. I like that people leave the theater and have a good smile on their faces.

An abridged version of this interview is featured in the March/April 2019 issue of The Saturday Evening Post. Subscribe to the magazine for more art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

Image Credit: Shutterstock.com

Who Has Played Their Iconic Character the Most?

Most actors dream of getting work. When those jobs become a regular thing, it’s a big win. When a role becomes something that you can comfortably revisit, then that performer has entered a completely different realm of celebrity. Quite a few actors have played iconic characters a few times, but the rarer air is saved for the ones that revisit the same role many times, sometimes across decades. With discussions raging about Marvel’s inevitable recasting of Wolverine and the identity of the next person to don the cowl of Batman, it’s a great time to answer the question, “Who Has Played Their Iconic Character the Most?” Follow the footnote to see how we set our rules and to learn more about some of the people that made dozens of appearances in the cheaper Westerns of the day.

From here on in, we’re going to break it down from a cut-off of SEVEN appearances or more. So sorry to the likes of William Powell and Myrna Loy (The Thin Man series), Ian McKellan (Gandalf), and the rest of the 6-Timers.

The Sevens:

- Tobin Bell (Jigsaw in the Jigsaw series).

- Vin Diesel (Dominic Toretto of the Fast and Furious franchise).

- William Shatner (Captain Kirk, of course).

- Patrick Stewart (Professor Charles Xavier in the X-Men films; he was Captain Jean-Luc Picard in only four Star Trek films).

- Brad Dourif (Chucky).

- Peter Cushing (Baron Frankenstein in the Hammer Studios films).

- Sean Connery (James Bond).

- Roger Moore (also James Bond).

- Judi Dench (M from the Bond series).

- Some people will try to convince you that Doug Bradley belongs here or on the Eight list for his turn as Pinhead in the Hellraiser series, but those started to go straight-to-video at about the mid-point. However, we’ll recognize five Harry Potter cast members here: Maggie Smith (Professor McGonagall), Mark Williams (Mr. Weasley), Julie Walters (Mrs. Weasley), Matthew Lewis (Neville Longbottom), and Alfred Enoch (Dean).

The Eights:

- Chris Hemsworth as Thor (get used to the Marvel Cinematic Universe, readers; Hemsworth racked up his appearances in the three eponymous Thor films, the soon-to-be-four Avengers films, and his brief appearance in Doctor Strange).

- Percy Kilbride (Pa Kettle in the series of the 1940s and ’50s films).

- Peter Lorre as Mr. Moto in that detective series.

- Robert Englund as Freddy Kruger (plus a TV series, and possibly another film).

- Leonard Nimoy as Star Trek’s Mr. Spock (remember that he skipped Generations but was in the reboot and Star Trek: Into Darkness).

- Sylvester Stallone as Rocky Balboa (the Rocky series, plus the recent Creed films).

- Fourteen members of the cast of the Harry Potter franchise have played their roles eight times, including Daniel Radcliffe (Harry), Emma Watson (Hermione), Rupert Grint (Ron), Robbie Coltrane (Hagrid), Tom Felton (Draco Malfoy), Bonnie Wright (Ginny), James and Oliver Phelps (Fred and George), Alan Rickman (Snape), Warwick Davis (Flitwick), Devon Murray (Seamus), Josh Herdman (Goyle), and Geraldine Somerville (a bit of a technicality, but she’s Lilly Potter in some form in every film, even as a photograph or a ghost).

The Nine: We’ve got one nine, but she’ll be a 10 soon (no pun intended). That’s Scarlett Johansson, who has appeared as Natasha Romanoff/Black Widow in nine MCU films since 2009 (including this April’s Avengers: Endgame). She will be headlining a Black Widow solo film around 2020, which will take her to 10. For the record, the films are: Iron Man 2, all four Avengers films, Captain America: The Winter Soldier, Captain America: Civil War, Thor: Ragnarok (the Hulk watches the video of her message to him), and Spider-Man: Homecoming (a bit dicier, and certainly archive footage, but she’s clearly in the phone video that Spider-Man took of the airport fight in Germany).

The Tens: This is rare air, but still a surprisingly big group.

- Robert Downey Jr. as Tony Stark/Iron Man (three Iron Man, four Avengers, Incredible Hulk, Captain America: Civil War, Spider-Man: Homecoming).

- Chris Evans as Captain America (three Caps, four Avengers, Spider-Man Homecoming [love those safety videos], Thor: The Dark World [Loki in disguise, but he had to show up and put on the costume], and Ant-Man).

- Marjorie Main as Ma Kettle (Kilbride was only in eight because he left the series and was recast).

- Christopher Lee as Dracula in the Hammer Studios films.

- Samuel L. Jackson as Nick Fury across the MCU (plus two episodes of Agents of S.H.I.E.L.D. on TV).

- Hugh Jackman as Wolverine (you might be surprised by this one, but remember that he was in three solo Wolverine films in addition to the other X-Men movies. We’re also counting that archival appearance in Deadpool 2 because it’s hilarious).

The Elevens: Anthony Daniels has played C-3PO in 11 Star Wars films; he appears in all three films in all three trilogies (Star Wars IX is due in December), Rogue One: A Star Wars Story, and voices the character in the Star Wars: The Clone Wars animated theatrical film. He also deserves recognition for doing the character for the Star Tours ride at the Disney Parks, the universally reviled Star Wars Holiday Special, an episode of The Muppet Show, The Lego Movie, Ralph Breaks the Internet, on radio adaptations, and as a voice actor in every Star Wars animated series from 1985’s Droids to the present. In other 11 news, Bernard Lee played M in 11 James Bond installments. We’ve also got Tyler Perry, who will be playing his famous creation Madea for the 11th time in March’s A Madea Family Funeral; Madea is another character with a rich multi-media life, having also appeared in a number of Perry’s plays, TV series episodes, and a direct-to-video animated film.

Twelve: Olympian Johnny Weissmuller won five golds for the United States as a swimmer. As Tarzan, he found box office gold in a popular series of films from 1932 to 1948. Amazingly, that’s NOT the character he played in the most films. We’ll get there.

Fourteen: The duo of Basil Rathbone and Nigel Bruce played, respectively, Sherlock Holmes and Doctor Watson in 14 films from 1939 to 1946; many modern artistic interpretations of the characters draw from their appearance in the films. Also at 14, Lois Maxwell played Miss Moneypenny the most in the Bond franchise.

Sixteen: Johnny Weissmuller knew that he couldn’t play the shirtless Tarzan forever. In 1948, he began the role of Jungle Jim in a film adaptation of the comic-strip character’s adventures. He’d go on to play Jim 16 times on film through 1956, and then in 26 episodes of a television series. Another 16 entry is Mickey Rooney, who played Andy Hardy in a series of family comedies; the films stretched from 1937 to 1946 with a final installment in 1958.

Your Solo Winner at Seventeen: From 1963 to 1999, Desmond Llewelyn played the beloved Q in 17 of the James Bond films. The inventor of Bond’s gadgets, Q’s frequently humorous demonstrations of his inventions delighted audiences.

Tag-Team Champions at Twenty-Eight: Though we’ve waffled a bit in terms of some of the cheaply made films of earlier decades, this overall achievement needs to be noted. Together, Arthur Lake and Penny Singleton played the characters of Dagwood and Blondie Bumstead in 28 movies from 1938 to 1950. Moreover, the duo would continue their roles on the radio, and Lake would go on to the play the comic-strip character on television for a 26-episode series in 1957.

There you have it. As you can see, the list is constantly in flux, and a number of actors (notably Stallone, Diesel, and those still active in Star Wars and the MCU) have a chance of increasing their ranks in the next few years. And though it takes longer than a week to make a movie these days, we shouldn’t completely discount those early days of Hollywood. If there’s a lesson here, it’s that the familiar can be fun, and we’ve been on the sequel train for a long, long time. The showbiz axiom may be to leave them wanting more, but very few studios went broke by giving the people what they want.

Footnote: Here’s an explanation of some of our criteria. We’re not counting serial installments of the 1930s era as individual films, which some people do when they tackle this question, or straight-to-video releases (sorry, Jim Varney/Ernest). We’re also going to keep the focus on American films (or co-productions where U.S. studios were a partner); that excuses Japanese actors Shintaro Katsu, who played the blind swordsman Zatoichi in 26 films and a 98-episode TV Series, and Haruo Nakajima, who donned the Godzilla suit in 12 movies. Also, we’re leaving out people that essentially played themselves, like Western mainstay Gabby Hayes (27 times) and Laurel and Hardy (an astounding combination of 107 feature films, silent films, and shorts with sound).

The early Westerns present some challenges for this kind of round-up, too. We’re also going to set aside an interesting but bizarre subcategory of actors that played the “same” character as sidekicks to various heroes across several series of Westerns; that includes Robert Blake (Little Beaver), Dub “Cannonball” Taylor, Smiley Burnette (aka Frog Milhouse), and Al St. John (Fuzzy Q. Jones) who played their sidekick roles a respective 23, 52, 62, and 85 times alongside the likes of Red Ryder, Davy Crockett, Daniel Boone, Wild Bill Hickok, and more. Similarly, we’ll acknowledge a few actors that played their western leads an incredible number of times, but the truth is that many of these films were shot so quickly in succession, some in a week, that it defies the expectation of what it takes to play a character across an ongoing series of films when you’re also working on other projects. For many of these actors, their job was to “be” this character on a near constant basis, which is a brand of filmmaking that’s more closely associated today with television. Among those actors are Roy Rogers (79 as “Roy Rogers”), Gene Autry (also as himself, 87), William Boyd (Hopalong Cassidy, 65), and Charles Starrett (The Durango Kid, 61). The Dead End Kids/Bowery Boys comedy series did something similar, with the likes of Huntz Hall (47 as Sach; 17 as Gimpy) and Leo Gorcey (41 as Slip; 21 as Muggs). Back to top.

Featured image: Shutterstock.com

An Interview with John C. Reilly

John C. Reilly has played such a diverse and unpredictable range of characters that it’s hard to keep track of them all, especially since he so completely takes over each role. He got lots of laughs in comedies like Talladega Nights and Walk Hard while surprising Hollywood with his depth as a dramatic actor in films like Gangs of New York, Boogie Nights, and Magnolia. His performance crooning “Mister Cellophane” in the musical Chicago even earned him an Oscar nomination.

Four of his latest movies showcase the depth of his versatility. Ralph Breaks the Internet brings back Wreck it Ralph for giggles. The Sisters Brothers is violent and hilariously down and dirty with Joaquin Phoenix. Holmes and Watson has Reilly rejoining Will Ferrell for a comic mystery.

And then there’s Stan and Ollie, his Laurel and Hardy project, in which Reilly plays Oliver Hardy — fat suit and all — opposite Steve Coogan. It focuses on the bromance that kept the classic comedy pair together even when they were falling apart. Reilly admits he was scared to death to play his comic hero, but he confesses, “I couldn’t stand the idea of anyone else doing it. There I am — humility and ego in one package.”

Reilly never slouches into a room wearing blue jeans. He makes an entrance, usually in a jaunty hat, a suit with a stand-out vest, and a notable pair of shoes from his vast collection. He always bowls you over with his glad-to-be-here attitude.

Jeanne Wolf: I actually watched you shed a tear as you watched a clip from Stan and Ollie. Why that emotion?

John C. Reilly: I guess it’s a little bit immodest to cry at your own film, but once you separate from making it and get to watch as an audience member, it’s different. The things that we explore in the movie about Laurel and Hardy are very touching, and I was thinking about what life was like for these two guys. It was bittersweet. We delve into the more complicated aspects of their up-and-down relationship, which mixed comedy with tragedy.

But you also get a sense of what it took to make their brilliant physical comedy look so easy and natural — the simple little gags, like the double door routine that’s in the film, where we keep missing each other and we go in one door and out the other and in the other and out the other. It’s very funny but requires almost a symphonic orchestration behind the scenes. You’re doing all of that almost like a dance inside your head. To make it look casual requires hours and hours and hours of rehearsal, and believe me, Steve and I did our share to get it right.

I appreciated that because I do a lot of physical shtick and I’ve learned not just from Laurel and Hardy but Buster Keaton or maybe Chevy Chase. I try to do realistic character stuff. I am not really trying to do pratfalls or whatever.

JW: First you were thought of as a comedian, but now you’ve done very dramatic roles as well. How do you see yourself?

JCR: I’m an actor because that’s what I’ve been since I was a little kid. It’s just something I always did. I like experiencing things and sharing them through a character because it makes me feel connected to people. I almost became a clown actually. My plan was to go to clown college after I finished acting school. And then somebody talked me out of it who was a clown. They were like, “No man. It’s a five-year contract and you have to ride in the worst compartment of the train. It’s a nightmare.” So I reconsidered. But I think I figuratively joined the circus when I started doing theater when I was 8 years old. That’s when I found my people, my fellow freaks.

As for going for laughs, a lot of comedians are desperate for them because, I don’t know, their mom and dad didn’t laugh at them or something. I’m not one who is craving to fill some missing place inside of me with laughter

JW: When you’re going for laughs you seem pretty fearless.

JCR: I’m not in the matinee idol business, where people are judging me about my body or whatever. When you’re doing comedy you can’t go, “I’ll chase the joke only so far and stop.” I learned that from Will Ferrell, actually. You commit all the way, and you must throw everything you have in the line of fire, including your body, your dignity, your reputation. Watching Will run around in his underwear for Talladega Nights was a big inspiration. I was like, “Man, that guy is brave.”

I think I figuratively joined the circus when I started doing theater. That’s when I found my people, my fellow freaks.

I don’t think there’s a big difference between comedic and dramatic acting. You push yourself to do it as honest and as real as you can. And I learned to improvise, which is freeing. It’s like you are letting your subconscious loose, and a lot of times the funniest stuff that you come up with has some basis in your real life and your real experiences.

I guess I’m sort of a chameleon. I don’t really know who I really am. I think I’m sort of a sum of my characters, to tell you the truth. I’m the Special Forces of character actors. I don’t mind. I was just a kid from Marquette Park in Chicago. I’m glad to be in the crazy world of Hollywood, and I’m having fun. I don’t worry about who’s the top dog; I’m just glad to be part of the game.

I think you need to be ready for luck. When luck comes knocking at the door, people have their pants off and they’re not ready. I’ve worked with many great actors, all along the way, brilliant, gifted people who just don’t get the break that you got or didn’t take it. Anyone with a sense of humility or knowing the way the world goes for actors knows that there are hundreds of people behind you in your path who didn’t get lucky.

JW: You describe yourself as a homebody. But you have to be out in public.

JCR: I only truly feel strange about it when I’m cornered by people that make me feel uncomfortable. I stay away from a lot of that stuff. I think you can kind of create your own reality to a certain extent. It can be a real freak show at times, but I have it easy compared to some people. So I’m not complaining.

JW: How do you react when you watch yourself?

JCR: Normally, I see my movies just once. I just get filled with regrets if I watch my stuff too much. I feel like, the older you get and the more experienced you get, the more, when you look back at your older work, you find yourself going, “Oh, I should have done this, I should have done that.”

A lot of filmmakers hate test screenings. It’s like this thing that the studio forces them to do. They go there, and they’re like, “The audience has to tell us what the movie is going to be. What a drag.” But I realized it’s where you can learn what is hitting with the audience.

JW: You’ve worked often in duos, with a strong co-star. Ever had any moments when the connection just wasn’t there?

JCR: My worst experience with another actor was in Walk Hard: The Dewey Cox Story with Willie, who happens to be a chimpanzee. We did a scene where I kiss him. In the first version, I’m saying, “No one understands me. You’re my only friend.” I have this real heart-to-heart talk with the chimp. And Jake Kasdan, the director, was like, “It’s almost too sweet. Maybe you should get mad or something.” And then I did a take that ended up in the movie, where I go, “I’m sick of all this crap. All you care about is fruit and touching yourself!” And I get up and storm off. And I thought, “Whatever. He’s a chimpanzee. He’s not going to notice what I do from take to take.”

I came back, and the look on Willie’s face was heartbreaking, this shocked, hurt look. And I was like, “Oh, Willie. I’m sorry.” He was a little tentative at first, and then he reached out and wanted to hug me. And I hugged him and said, “It’s okay. It’s okay.” And we did the scene a few more times, and I’d yell at him again.

Eventually, he started to understand, “Oh, it’s like a game. You do that.” He even started to play with me and show his teeth like, “I can be angry at you, too.” But by the end of it, we were really great pals. It was sad to see him go.

Photo by Gage Skidmore