Saturday Evening Post Time Capsule: October 1938 – Aliens and Fascists

See all Time Capsule videos.

One of the illustrations by Henrique Alvim Corrêa for the original publication of H.G. Wells’ The War of the Worlds (1906)(Public Domain Review)

Behind Every Successful Dictator…

After nearly 10 years of courtship, Eva Braun must have been asking herself the question on a daily basis: Is Adolf ever going to propose? Her family was wondering, too. Eva had spent so much time with Adolf Hitler, and for so long, that Europe was starting to talk.

Even the British were wondering about Adolf Hitler’s intentions. An American ambassador reported that many in Great Britain wanted to know when “that Hitler person would get married and settle down.” Maybe they assumed Hitler’s conquest of Europe was the sort of thing a bachelor might get up to, with an abundance of time and energy. (At 50 years of age, Hitler was a little old to be sowing wild oats.) Still, there was the hope that a wife could find a positive outlet for all that conquering energy.

Eva must have felt she was well qualified to be Frau Hitler, or she wouldn’t have stuck with Hitler so many years. In his December 16, 1939, Post article “Is Hitler Getting Married?” Richard Norburt reported information “from sources inside Germany which we have always found dependable” that the two had been carrying on their “colorless little love affair” for over a decade.

But wedding bells wouldn’t be ringing for the Hitlers any time soon. As the Führer told a women’s organization in Nuremburg, “I should love nothing more dearly than a family. … When I feel I have accomplished my historical mission, I intend then to enjoy the private life which I have hitherto denied myself.”

That wasn’t soon enough for the Braun family. They decided to put some pressure on Hitler to name a date. Unfortunately, they chose a bad time to confront Hitler (which was pretty much any time). In late August of 1939, as Hitler was feverishly putting the final touches on his invasion of Poland, a group of Eva’s female relatives drove down to Salzburg to tell Adolf he’d better do the right thing by their “Evi.”

Hitler was a master negotiator. He dodged the family’s ultimatums, but soon after their Salzburg meeting he “ordered part of his personal suite in the Chancellery [his Berlin headquarters] prepared for Evi’s use, and she promptly moved in.”

As part of Hitler’s official household, Eva became a cheerful hostess at Hitler’s Bavarian mountain home. She liked to cook for Adolf, and specialized in preparing the vegetarian dishes he liked. In her spare time, she enjoyed making rag dolls, taking photographs, and reading detective stories. Once, she had enjoyed playing the accordion, but she traded it in for a mandolin, perhaps believing the squeezebox was not refined enough for the Third Reich.

She was showing her support for the war effort by saving fuel. She stopped driving the Horch limousines Hitler had given her, preferring an ivory-colored Volkswagen. She tried to stay informed on news of the war. Perhaps she hoped that someday, as Frau Hitler, she would help Adolf in his great mission, discussing strategy with him and helping with his negotiations. As Richard Norburt reported, “A few weeks ago, when the German minister to Denmark returned to Berlin to consult with Hitler, the two men walked together in the garden of the Chancellery. After a little while they were joined by Evi, and Hitler’s guards were amazed to see her actively participating in their sober conversation.”

(Image courtesy Wikimedia Commons)

Until the day when Hitler got down on his knee to propose, she spent her days sunning herself on the stone porch at Hitler’s house in the Bavarian mountains. There she would smile at visitors, engage in small talk, be pleasant, and wait for Adolf to get out of his meetings.

And in those empty hours, maybe she envied the family life of Europe’s other dictators.

Spain’s General Francisco Franco, for example. He had proposed to María del Carmen Polo y Martínez-Valdés in 1923, but had postponed the wedding when the Spanish king promoted him to command the Spanish Foreign Legion. Yet, unlike Hitler, Franco had only put off the wedding a few months, not years. He and Carmen Polo were married that October, and by 1939 were raising a teenage daughter.

And then there was Benito Mussolini — Italy’s fascist warlord who wasn’t shy around women. He had married Rachele Guidi in 1915, and had fathered six children by 1939. Guidi was devoted to Mussolini, though Il Duce didn’t seem to reciprocate that devotion.

And even Hitler’s ally Joseph Stalin was a family man, of sorts. Though a widower in 1939, he had been married twice and had three children.

All the other dictators were starting families. What was Adolf’s problem?

Eva probably didn’t know that life with a dictator was often bitter and short. She, like most of Italy, couldn’t have known that when Mussolini married Rachele Guidi he was already married to Ida Dalser and had a son with her. Instead of seeking a divorce to Dalser, he simply denied he’d ever been married to her, then ordered government agents to destroy any records of the marriage. Still insisting she was married to Il Duce, Dalser was eventually detained, against her will, in a psychiatric hospital where she died in 1937. Their son was put up for adoption. He grew up and enlisted in the Italian Navy. But, like his mother, he refused to be silent about the marriage. He continued to assert that Mussolini was his father. He, too, was sent to a psychiatric hospital, and soon after, died there.

Stalin’s case was even more sinister. In 1906, he’d wed Ekaterina Svanidze in the Russian province of Georgia. They had a boy before she died of tuberculosis the following December. In 1919, Stalin married again. His new wife, Nadezhda Alliluyeva, gave birth to a boy and a girl. Yet, as anyone — other than Eva Braun, maybe — might have expected, marriage to a dictator was not as much fun as it looked. Alliluyeva learned, as did all of Russia, that Stalin was very hard to live with. The couple frequently argued and, in 1932, after they quarreled bitterly at a party, she went home and shot herself.

Stalin appeared to have been fairly affectionate toward his daughter, Svetlana. He didn’t care much for either of his boys, though, probably because he didn’t see any promise of a ruthless dictator in either of them. Bullied by his father, the eldest boy, Yakov, shot himself, but survived. (“He can’t even shoot straight,” Stalin is reported to have sneered.) Yakov joined the Red Army, was captured, and died in a German concentration camp. His stepbrother, Vasily, survived the war but, after Stalin’s death, was sentenced to eight years in a labor camp. Svetlana defected to the U.S. in 1967.

It’s possible Eva would have stuck with Adolf even if she’d known what had happened to the other dictators’ families. She remained with him even though she must have known of his murderous policies, the millions of deaths he ordered. But she was, in her quiet way, as much a fanatic as him.

She hoped to share his dream, but wound up in his nightmare. Eva and Adolph married, at last, on April 29, 1945. The couple enjoyed a short, underground honeymoon before committing suicide the next day.

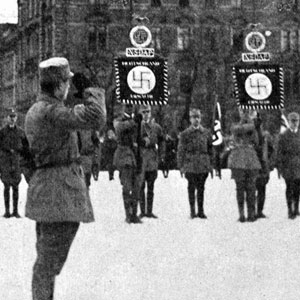

Those Wacky Nazis

Years after Adolf Hitler had been Germany’s dictator, many Americans still couldn’t take him seriously. They’d seen him in newsreels, waving his arms and screaming, acting like a complete lunatic. They’d laughed at his imitators — Moe Howard of the Three Stooges or Charlie Chaplin — who’d portrayed him in movies as a ranting, bumbling egomaniac. Far from the realities of life in Europe, Americans found it hard to take Hitler seriously, particularly when the media liked presenting him as a humorous sidelight in the news.

This was how he was treated when the Post first took notice of him. Sensing the whole National Socialist Movement was a quaint joke, the Post editors sent a writer who’d present the Nazis as humorously as possible.

Kenneth L. Roberts was a frequent contributor and a critic of just about anything new or foreign. The editors could rely on him to write a scathing report of extremist politics in Weimar Germany. They couldn’t have been disappointed with his dismissively titled “Suds,” which appeared in the October 27, 1923, issue. Asserting that beer was the guiding force in German politics, the article was illustrated with two barmaids demonstrating their remarkable grasp of the issues. (Click Here to read the entire article from the Post.)

Roberts opened his piece by establishing his contempt for Germans. “In certain respects Berlin is the center of Germany. It is the seat of government. There the heads are the squarest, the prices are the highest, the banks are the largest, and the buildings belong to the most violent neo-German school of architecture. … There is more depravity in Berlin than elsewhere in Germany, more gloom and depression, more of the newly rich off-scourings of other races, more of that wild German nightlife that is about as spontaneous and joyous as a Monday morning in a morgue. In such ways as these Berlin is Germany’s heart.”

Having sharpened his scorn on the German capital, he closed in on the southern province of Bavaria.

“One finds cement-headed plotting and foggy intrigue at its very apex. There is always a plot on foot in Munich — either a plot to push France into the Atlantic Ocean or to shove Russia across the Ural Mountains or to shoot somebody or to seize something. In Munich one finds the thickest ankles, the most peculiar garments … the wildest rumors, the roundest heads … and a more passionate devotion to the consuming of beer than exists in any other part of the known world … that beer plays a more powerful part of the life, custom, and activities of the Bavarians than almost anything else.”

His condescension toward Germany probably arose from the contempt many Americans felt for the country they had defeated in the last war. Americans had little understanding or sympathy for the country’s civil unrest, unstable government, skyrocketing inflation, or the German character.

“A Bavarian,” Roberts continued, “who is full of an evening’s accumulation of his favorite bräu will frequently burst into tears over the most trivial occurrences. … [When] a flannel-mouthed German orator becomes inflamed by beer and feels obliged to rise to his feet and find fault with the world in general … the beer drinkers pound the table with their firsts, hiccup openly, and agree vociferously that the speaker has given tongue to the Wisdom of Solomon.”

Hitler was, to Roberts, just another flannel mouth. A very ordinary person, he concluded, but a great talker with a detailed agenda. As leader of the National Socialist Workers’ Party, Hitler had made a list of demands to the Allied powers, which naturally included releasing Germany from the penalties imposed by the Versailles Treaty. It also demanded punishment for war profiteers, non-Germans, and, especially, Jews.

“There are several other demands on Hitler’s list,” Roberts wrote, “including a few that are never made public. In fact, whenever he thinks of anything new to demand he demands it. Demands don’t cost anything”

Roberts frankly admired the fascists of Italy and thought that a little fascism — if such a thing is possible — would be good for America. But he had only scorn for these Bavarians, who did little more than issue demands and play soldier. When the weekend came, “the Bavarian Fascisti sportively line up in military array,” Roberts wrote, “march 10 or 15 miles into the country until they reach a likely terrain, and then proceed to march, countermarch, issue hoarse orders, discipline each other, kick dust up each other’s backs, dream, hope, conspire, plot, and otherwise have a full day of South German sport and social activity.”

Roberts had the perspective of a man who viewed foreigners with contempt. He also had the view of a man who regarded Germany without getting out of his car. For example, he believed everything you needed to know about Bavarians could be learned by how poorly they gave travel directions. Ask anyone in France for directions, he said, and they “almost invariably understand the question and instantly hurl back accurate answers. The Bavarians, no matter of what age or condition of life, never understand, don’t particularly want to understand, and are usually incapable of answering after understanding has been forced on them.” He didn’t like the bicycle riders any more. “Finding himself directly in the path of an approaching automobile … the Munich bicyclist rides serenely on his way, leaving it to the automobilist to run his machine into a tree, drive it through a shop window or drop dead from heart failure.” He probably thought the Sauerbraten was overdone, the beds were lumpy, and — from what I’ve read of him — the waiters were insufficiently respectful.

With Hitler and the Germans portrayed as such laughable goons, it’s no surprise Americans dismissed the Nazi threat for so long.

Step into 1939 with a peek at these pages from The Saturday Evening Post 75 years ago:

A Look Inside Germany’s First Conquest

courtesy Wikimedia Commons

By coincidence, a Post article about Czechoslovakia, the first nation conquered by Hitler, appeared just as he was grabbing up his second.

“Nazi Germany’s First Colony” appeared in the Post on August 26, 1939, the day Hitler had originally planned to invade Poland (Read full article here). But his plans were pushed back, and the issue was still on newsstands when Hitler’s armies crossed the border into Poland on September 1. The ensuing blitzkrieg, which brutally crushed all Polish resistance, had little in common with the swift, bloodless conquest of Czechoslovakia.

The Czech republic had already been reduced when Great Britain and France allowed Hitler to occupy its borderlands in 1938. The next year, he returned to grab the remaining provinces of Bohemia and Moravia through threats of invasion. United Press reporter Edward W. Beattie Jr., who was in Czechoslovakia at the time, described the curious manner of the German invasion.

After bribing a taxi driver to take him toward Germany’s advancing forces, Beattie was startled when German scouts suddenly appeared, moving rapidly, coming down the road toward him: “When we met them head-on, the driver tried frantically to turn. It was too late. The unit began passing us. The officer in command leaned out over the side of [his] scout car. I thought he was going to ask for identification but all he said was: ‘From now on in this country, you drive on the right-hand side of the road.’ The occupation was as easy as that” (collected in They Were There: The Story of World War II, edited by Curt Riess, Garden City Publishing, 1945).

Step into 1939 with a peek at these pages from this week’s Post, 75 years ago:

There was no violence, no popular uprising, no guerilla warfare. The Germans simply took up residence in the capital city, Prague, and began appropriating what they wanted. Resistance was reduced to futile gestures, like the one Beattie recounted when he and other foreign correspondents had visited a nightclub. Taking advantage of their journalistic immunity, the reporters ordered the band to play “It’s a Long Way to Tipperary,” “Over There,” and other Allied songs from the First World War. In a scene reminiscent of the movie Casablanca, the songs made “a couple of dozen German officers at other tables [get] more and more restless.

“Finally two officers a short distance away pounded for silence,” Beattie wrote, “and one of them came over and demanded that we stop ‘insulting the German army.’ Later in the evening, when everyone was drinking pretty heavily, he drew me to one side and said, ‘You don’t think we like this sort of thing too much, do you? For God’s sake, let us try to make this occupation as decent as possible.’ (The army’s part in the occupation was decent in every way. Of course, the Gestapo and the S.S. arrived later.)”

Beattie’s observation was echoed by the Post’s foreign correspondent Demaree Bess: “Greater Germany has planted her first colony in the heart of Europe. Bohemia and Moravia … have become as much of a colony as any island in the South Seas. The Czechs have assumed the inferior status of natives. … [They] do most of the work and the Germans pull all the wires.” It was the Germans’ goal to turn the republic into an efficient workhouse and profit center for the German Reich.

In these early days, they were careful not to make their exploitation too obvious. As Bess wrote, the Germans still hoped to win the cooperation of Czech workers and industrialists. At least that was the intent of the new government the Germans set up in Prague. Their biggest obstacle, it turned out, was other Germans — the Gestapo, the S.S., and officials of the Nazi party.

Nazi officials descended on Prague with the sole purpose of enriching themselves. They were soon disrupting Czech manufacturing by raising production quotas while limiting managers’ profits. The Nazis were further disrupting the economy by ruthlessly exploiting the Jews.

“When the Germans entered Prague without warning last March, they made it clear at once that life would become intolerable for Jews,” wrote Bess. “Thousands therefore went to the German secret police to apply for permission to leave the country. They were told their applications could not be filed until they had made ‘satisfactory arrangements’ with a Nazi-controlled bank, which demanded full powers of attorney over their property.”

The full savagery of Nazi domination was still in the future. But already, under German rule, life was becoming miserable for the Czechs. Consequently, Bess reported, “I know of only one European country today whose people, in very large numbers, actually desire a general European war. That country is the German protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia. The Czechs say they have discovered that some things are worse than modern war.”

They were about to find out that modern war could be much, much worse.

Listen to President Roosevelt’s August 28, 1939 address to the Herald-Tribune Forum. In talking about the need for peace, he is already distancing himself from the old policy of peace by appeasing Hitler.

Listen to a radio speech on the BBC given on August 27, 1939 by Jan Masaryk, the former head of the Czech nation. He had seen his country betrayed by his allies, Great Britain and France, who allowed Hitler to seize first the border regions of Czechoslovakia, then the entire nation, rather than go to war with Germany.

Listen as Adolf Hitler justifies his invasion of Poland to an ecstatic Reichstag.

Meanwhile, as you’ll hear, Great Britain and France are hurriedly summoning their governments to respond to Germany’s aggression.