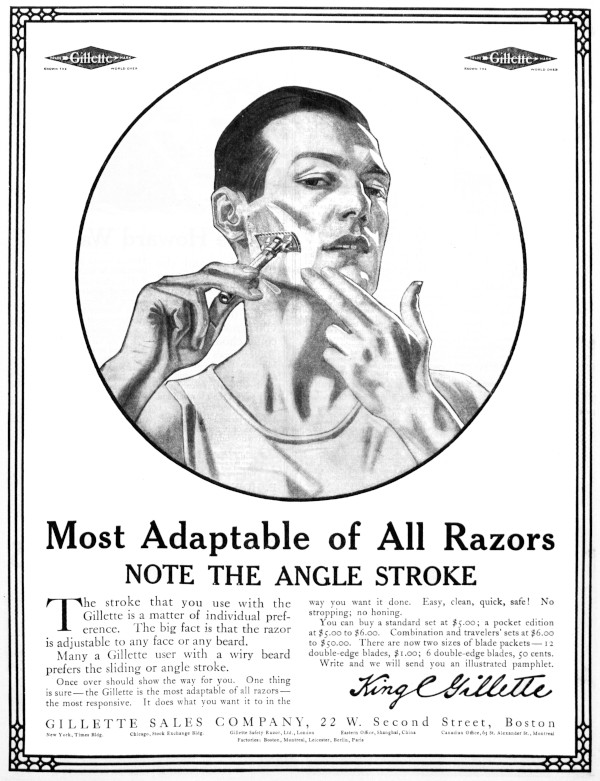

Vintage Advertising: Gillette Safety Razors Make the Cut

For centuries, men relied on straight razors to remove their beard stubble. These long steel blades with a hinged handle could give a smooth shave if regularly sharpened and expertly handled. But they could inflict wicked cuts on the inattentive shaver.

Then, in 1903, King Camp Gillette introduced his safety razor with a disposable blade held underneath a protective guard at just the proper angle. And if this wasn’t enough, Gillette’s razors had two shaving edges instead of the single edge of a straight razor.

It was a good design and reasonably priced, but many men remained faithful to the straight razors. Then came World War I, and the Army’s prohibition on beards, which prevented gas masks from fitting tightly, not to mention being good nesting places for lice. The government bought 4.8 million of Gillette’s razors and issued them to men in uniform. By the time the men returned home, the era of straight razors was over.

This article is featured in the November/December 2020 issue of The Saturday Evening Post. Subscribe to the magazine for more art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

Featured image: SEPS

Vintage Ad: Bite-Sized Bread Model

In 1942, Quality Bakers of America commissioned artist Ellen Segner to develop an identity for their new Sunbeam Bread. She was a good choice — a well-known illustrator who had painted all the characters in the iconic 1950s Dick and Jane books.

Marilyn Kille remembers modeling for the Miss Sunbeam character when she was 5. She recalls being intimidated by the photographer who kept disappearing beneath the black hood of his studio camera. She was placed on a tall stool and directed to take a slice of bread from a tray on her left. She was to then take one bite from a specified corner and, the photograph taken, let it fall into a trash bin on her right.

She followed the instruction but grew agitated the longer the session continued. Tears welled up in her eyes and soon ran down her face. Everything stopped. When the staff asked her what was wrong, she wouldn’t answer. The photographer decided he had enough photos and called an end to the session.

If you were a child in those years, you might remember being admonished never to waste food; there were “children starving in China,” after all. Taking those warnings to heart, Kille was crying because of the growing pile of discarded bread. She would surely be punished for wasting food and depriving all those hungry Chinese children.

This article is featured in the September/October 2020 issue of The Saturday Evening Post. Subscribe to the magazine for more art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

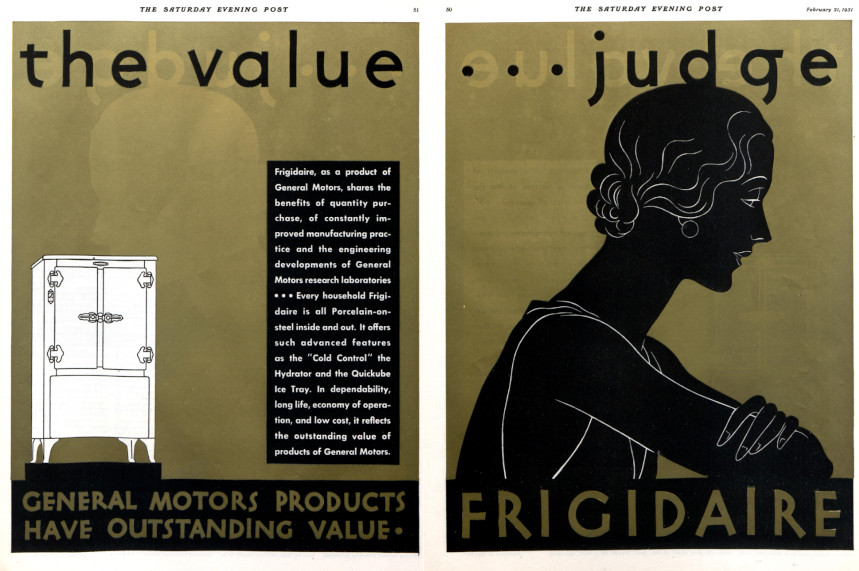

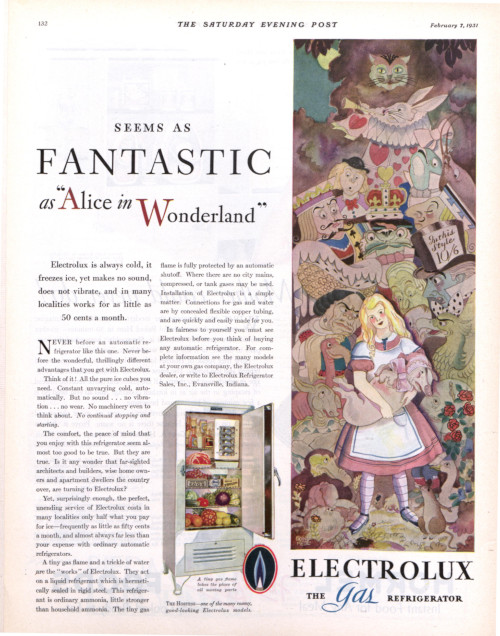

The Art of the Post: The Art of…the Refrigerator?

Read all of art critic David Apatoff’s columns here.

The first practical refrigerators were invented a century ago and instantly transformed American domestic life. The Saturday Evening Post was flooded with advertisements for the strange new devices. Illustrators were hired to help the public imagine how refrigerators would fit into a home and envision the role they could play. Some were more successful than others.

Inventor Fred Wolf of Ft. Wayne, Indiana started the rush in 1913, with the announcement of the first refrigerator for home and domestic use. A year later, an engineer in Detroit jumped in with his suggestion for an electric refrigerator, the predecessor of the famous Kelvinator. By 1918, the demand for the new invention had become clear, and the Frigidaire company was founded to mass produce refrigerators.

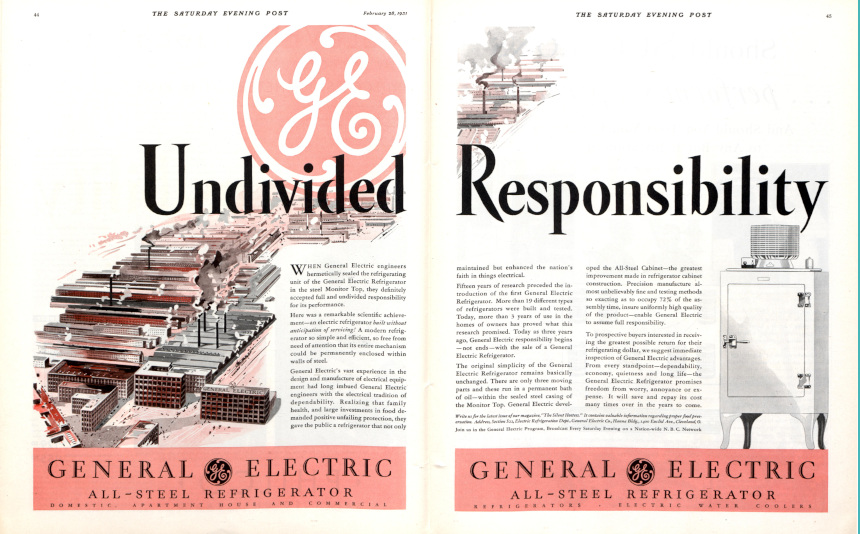

Rival companies popped up, each trying to outdo the others with features they thought the public might like. For example, Kelvinator touted the first refrigerator with an automatic control. Electrolux offered what it called the first “absorption refrigerator.” Inventors and engineers battled over the science. Here is a two-page ad from the Post bragging about the factory where the “hermetically sealed refrigerating unit” is contained within the “steel monitor top.”

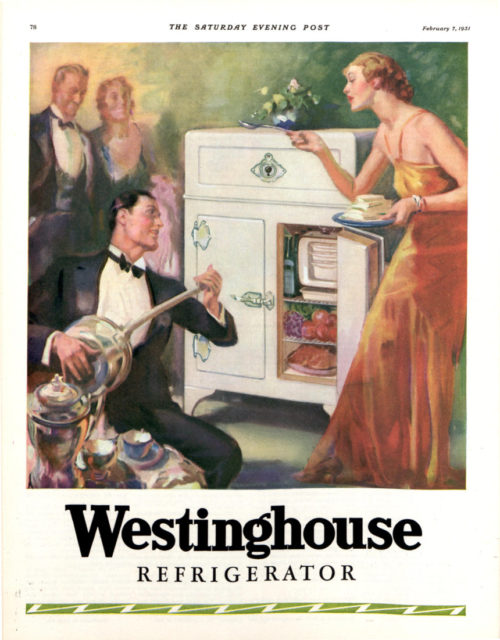

But it took art, not science, to humanize the strange new invention. Refrigerator companies faced a big challenge selling the new invention to everyday Americans; in 1922 a refrigerator could cost over $700 while a new car (the Model T Ford) cost only $450. The public wouldn’t buy refrigerators without a vision for how they would fit into the American lifestyle.

Here we see a 1929 painting by Walter Biggs of a high-class social event:

The men are wearing tuxedos and the women dressed in fashionable gowns. They smile as they exchange witty banter about cultural events. But the real star of the party—and the whole reason for the painting—is that brand new refrigerator in the far right hand corner.

Right smack dab in the center of the painting is the modern miracle… glasses filled with ice! Ice was readily available for guests for the first time with the invention of the refrigerator. Today we wouldn’t think of keeping our refrigerator in the middle of our dining room with the guests, but this picture tells us that it was a mark of prestige.

Next, this enterprising artist tries to portray the refrigerator as a springboard to romance. (Hah! Good luck with that!)

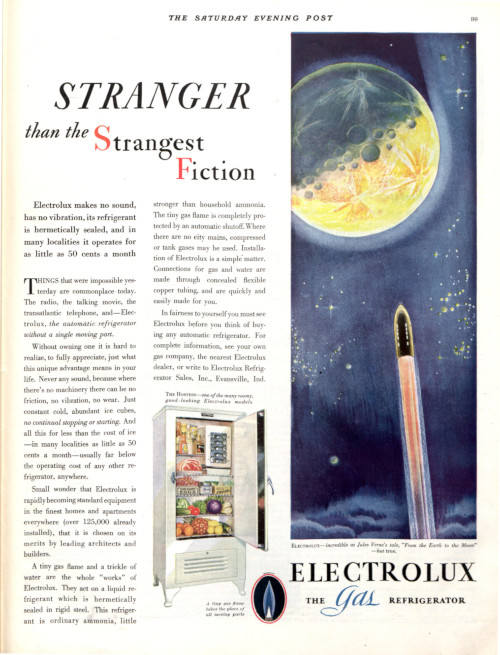

Another artist felt he could make the new invention popular with a “science fiction” approach:

This artist does his best to make a white metal cube look stylish by making it a tiny element in a large, black and gold art deco picture. Note that Al Dorne’s harried, overworked housewife has become an elegant young woman of leisure in an evening gown.

There were even illustrations for consumers who felt that a refrigerator was “like magic.”

Today many of these approaches seem silly to us, but in the beginning before the identity of the refrigerator had been firmly established, artists could let their imaginations run wild.

It always takes a while for people to figure out the proper role for the new invention; when trains first arrived on the scene, they were noisy and frightening. They spooked horses and polluted the environment with smoke and cinders. But artists and musicians and storytellers began to humanize the new machine, singing folk songs and telling tales, and pretty soon we welcomed trains into our cultural heritage.

We rely upon the artistic imagination to help us view our strange new inventions and assimilate them into our natural world. Nothing like the refrigerator had ever existed before, so there were no precedents for artists to rely on. Some of the earlier efforts make us laugh today, but eventually illustrators found their footing.

Featured image: Courtesy of the Kelly Collection of American Illustration

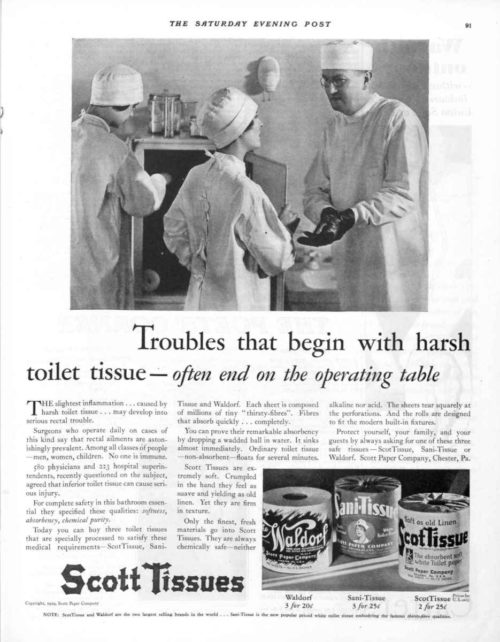

Vintage Advertising: Scott Toilet Paper Goes Negative

Early ads for the Scott Paper Company’s toilet paper emphasized the paper’s texture, calling it “soft as old linen.” But in the late 1920s, a new series of ads warned consumers that using the wrong toilet paper could lead to “serious trouble,” possibly requiring surgery.

When the Scott brothers began putting toilet paper on a roll in 1879, they had just one competitor, Joseph Gayetty’s “Therapeutic Paper.” These were loose, flat sheets, treated with aloe and promoted as “the greatest necessity of the age.” But for decades, most people relied on whatever paper was handy. In outdoor privies across the country, they might reach for a Sears Roebuck catalogue, which was kept there for a purpose the mail-order company never anticipated.

Scott Tissue offered the convenience of a paper roll, but its ads focused on its purity. Alternatives, they said, were somehow linked to the “65 percent of middle-aged men and women [who] suffer from rectal disease.” And some brands were found to contain mercury and arsenic. As good as Scott Paper was, there was still room for improvement. It wasn’t until 1935 that the Northern brand could advertise a toilet paper that was “splinter free.”

This article is featured in the May/June 2020 issue of The Saturday Evening Post. Subscribe to the magazine for more art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

Featured image: Shutterstock

Barry Manilow: The Surprise Jingle Hitmaker

Just hearing the opening line “Like a good neighbor…” necessarily invokes the rest of the earworm: “State Farm is there!” Although the lyrics aren’t currently in use in State Farm advertisements (ditched two years ago for the “Here to help life go right” campaign), the “Like a Good Neighbor” jingle has seemingly been the lifeblood of the State Farm brand for decades, like a radio hit that won’t go away. It makes sense, then, that the jingle was written by Barry Manilow at the start of his career in 1971.

He made 500 dollars for writing the song that would be used for years in different capacities in the insurance company’s advertising campaigns. It wasn’t his only foray into the industry, though. A young, prolific Manilow in the ’60s and ’70s wrote and recorded heaps of famous jingles. When he received an honorary award at the 2009 CLIO advertising awards, Manilow noted that writing advertising jingles was “the best music college I could ever imagine,” despite having studied at New York College of Music and Juilliard. “What I learned most of all in my jingle days was how to write a catchy melody,” Manilow said in an interview.

So the pop superstar’s hits like “Copacabana” and “Could It Be Magic” might not exist if he hadn’t spent years composing commercial tunes.

Manilow began his collegiate studies in night classes at City College of New York. He majored in advertising, because, as he claimed (in Patricia Butler’s 2002 biography), “The choices were listed alphabetically and advertising was first under A.” He didn’t stay with it long, however, taking a job in the CBS mailroom and eventually enrolling in the New York College of Music. Manilow stayed busy in the early years, taking piano gigs and composing a full musical score (The Drunkard) while maintaining his position at CBS. He also began writing and performing jingles for some leading brands.

His first paid tune was with Dodge. Then, Manilow wrote “Like a Good Neighbor” for State Farm and “Stuck on Band-Aid” for Band-Aid. He also sang in “Give Your Face Something to Smile About” for Stridex and “Finger-Lickin’ Good Day” for KFC. His big break, according to an interview with Chicago’s ABC 7, was the dramatic showstopper “You Deserve a Break Today” Manilow sang for McDonald’s.

While he was performing with Bette Midler at the Continental Baths in Manhattan and trying to jumpstart his own recording career, Manilow performed in Dr. Pepper’s “The Most Original Soft Drink” (written by Randy Newman) and “Join the Pepsi People,” and he even wrote “Bathroom Bowl Blues” for Green Bowlene.

Manilow often plays his famed jingles at concerts to his “Fanilows” who don’t mind if he stumbles over a lyric or two. While the enterprise of jingle-writing led to a lucrative recording career for Manilow, he scarcely made residuals on any of the still-familiar commercial tunes. State Farm still uses the nine-note hook Manilow wrote for them — now as a lo-fi, 16-bit soundtrack — but he hasn’t seen a dime from them since the initial 500.