Civil War Soldiers’ Final Reunion at Gettysburg

The old veterans couldn’t wait to come. Roads ran thick with automobiles and horse buggies. Most arrived on the nation’s sprawling rails. A few walked more than 100 miles. An 85-year-old man, fearing his son would prevent him from going, crawled out a window and caught a train.

Altogether, an estimated 50,000 of the blue and gray trekked to the Great Reunion, a grand commemoration at iconic Gettysburg, on that battle’s 50th anniversary: July 1 to 3, 1913.

Why did they go? According to the many politicians and generals who also came to the reunion, the reason was clear: There was an urgent need for unity. At that very moment, U.S. ground forces were in Cuba, Mexico, Nicaragua, and the Philippines. Trouble in the Balkans threatened to escalate into a much larger European crisis. Not mentioned but certainly pressing were the many bitter divisions at home. Conservatives were continuously fighting progressives over Jim Crow and lynching, female suffrage, overseas expansion, immigration, and labor rights. In this time of peril, so said the organizers, only the finest of military heroes could save our great nation.

But as the famous and powerful gave their speeches, exalting the virtues of suffering and death, the vast majority of the old soldiers spent their time at Gettysburg seeking something else: proof of life and a chance to heal.

“I will see if I can find the exact spot where I was struck with a federal ‘minnie’ ball.”

—Confederate F.O. Yates

For half a century, survivors of the nation’s deadliest war struggled with memories of combat, the loss of comrades to bullets and disease, recurring nightmares, and lingering visions of killing fellow humans. Just as crippling was the loneliness. As supportive as family and friends could be, veterans needed other veterans to talk to, and their numbers were dwindling. An aging James Vernon, formerly a young lad in the 18th Virginia Infantry Regiment, said of warfare, “Those who were not there can form no idea of it.”

Tradition credits a fellow veteran for proposing a final, encompassing Civil War reunion, one Henry S. Huidekoper of the 150th Pennsylvania Infantry Regiment, who had lost an arm at Gettysburg. In short order, Gettysburg businessmen and city officials adopted the idea, and within months the Pennsylvania governor and state legislature supported the project. A year before the anniversary, a commission of former high-ranking officers of the blue and gray solicited help from the federal government, and interest rapidly grew.

Six months out, it was evident that this was going to be a phenomenon. The Williamsburg, Virginia, Gazette predicted the reunion would be “the greatest gathering of conqueror and conquered in the history of the world.” Slated to speak were outgoing President William Howard Taft, Chief Justice Edward White, Speaker of the House Champ Clark, the newly elected President Woodrow Wilson, and a score of governors — plus bankers, business moguls, and time allowing, a few high-ranking Civil War officers. Every major newspaper was sending correspondents. The total budget for the affair, most of it coming from the Pennsylvania and New York state assemblies and the U.S. War Department, was $1.2 million (or about $31 million in 2019 dollars).

Yet only a few hand-picked veterans were invited to speak, and none were African American. Nor were nurses or other civilians given a chance to tell their story. The organizers expected perhaps 5,000 veterans would arrive by June 29, two days before the reunion’s official start. But the people came like a collective flood. When the number exceeded 18,000 that day alone, the hosting U.S. War Department scrambled to accommodate the overflow. By July 1, the start of the anniversary celebration, veterans and tourists had transformed Gettysburg into the third largest city in Pennsylvania.

Once on site, veterans were not making declarations of peace and unity. Instead, their first inclination was to find specific locations that held personal meaning. Frail and failing Hugh Meller of Fairport, New York, was determined to see the room at the Western Maryland Railroad Station where he had been held captive for two days. With the help of two men, he ascended a stairway to the second floor. “All these later years I have feared that the old station had been demolished,” Meller told a reporter. “How glad I was when I saw the familiar building upon my arrival.” Confederate F.O. Yates wanted to see precisely where he clashed with Union infantry on July 3. “I charged within 50 feet of the federal lines on top of Gettysburg Heights. I will see if I can find the exact spot where I was struck with a federal ‘minnie’ ball,” he said. Samuel Marks, who served with the 53rd North Carolina Infantry, found the hill where he had to leave his dying brother behind.

While exploring Seminary Ridge, where the warring parties tangled on the battle’s first day and from which Confederates launched their doomed “Pickett’s Charge” in the contest’s final hours, two strangers immediately recognized a shared trait: each was missing a right arm. An ensuing conversation revealed that both received their wounds within minutes of each other, only a few hundred yards apart on that same ridge.

While the politicians proclaimed that the old soldiers had moved on from the Civil War, in reality, sectional animosities lingered. Many Confederates arrived in gray uniforms, lofting Confederate battle flags. Unionists, predominantly in civilian attire, reminded them who had won. The general white Southerner consensus was that the war was an invasion, while Northerners considered the Confederacy treasonous. Yet they reached for each other, hoping to make sense of their shared traumatic past.

Seven Gettysburg survivors traveled together all the way from Phoenix, Arizona, even though they fought for different states — Georgia, Indiana, Minnesota, New York, Pennsylvania, and Virginia. Upon their arrival, the group retraced their steps, trying to piece together where each exactly stood and what had happened to them. After moments of initial confusion, the landmarks slowly became familiar, and the memories horrifically vivid. Yet in retelling their own struggle, they found understanding, empathy, even solace.

All the veterans came in hopes of finding fellow members of their old regiments. Unwittingly, reunion organizers made this very difficult: The vast “Great Encampment” was organized by state, but veterans were assigned to the area where they currently lived, not with the state they had served during the war. They were left to search a two-mile area, often with little or no knowledge of their comrades’ locations. Joshua Vinson looked in vain for fellow members of his Virginia cavalry unit. By sheer chance, Remi Boerner happened upon an old friend from the 91st Pennsylvania. The two warmly embraced, having not seen each other since 1865. Former Hoosier Frank Fickas searched among the 74 tents housing men from his old home state. “Is there anybody here from the 14th Indiana?” he beckoned. Finally, he saw a familiar face, and the man responded, “I’m here, Frank, the only one.”

At least one veteran lugged away a suitcase full of soil from the site where he had fought.

Such was the pattern throughout the week. When queried by his hometown paper, a North Carolinian said, “How did we put in our time? We scattered.” A journalist from the local Adams County News marveled at how this “national reunion” was instead predominantly intimate and personal. “The old soldiers by twos and threes found each other, and in camp or on the field they spent hours talking.”

The Commemoration officially began at 3 p.m. on July 1 in the Great Tent, an immense, sweltering canopy that seated 13,000. Lindley Garrison, the U.S. Secretary of War, was the day’s keynote. Like President Woodrow Wilson, who had appointed him, Garrison had no military experience himself. Still he felt qualified to pontificate grandly. “Fifty years ago today, there began here one of those conflicts between man and man, marked by such exhibitions of valor, courage, and almost superhuman endurance as to engrave itself upon the tablet of history,” he intoned. “Equal met equal, and in the domain of physical prowess all were worthy of medals of honor.” Garrison also contended that the veterans had put the past far behind them, claiming “the last embers of the former time have been stamped out.”

In speech after speech, bankers, congressmen, and governors proclaimed there existed a collective, patriotic, unifying amnesia. Notably, relatively few veterans listened to any of it. Heads of state implored veterans to forget, when they could not. “The arrival of the Secretary of War,” a reporter from the Philadelphia Inquirer observed, “stirred but passing interest in the hearts of the men … the vast majority [of veterans] spent the day out on the familiar old battlefield, in the tents of their comrades, or looking for the spots they occupied 50 years ago.”

Throughout July 2 and 3, the orations continued, placing veterans on pedestals — and consequently out of reach. On July 4, despite having initially rejected an invitation to attend, President Wilson arrived and delivered yet another ingratiating tribute to warriors and warfare. In a brief and stilted address, Wilson insisted “We are made by these tragic, epic things to know what it costs to make a nation — the blood and sacrifice of multitudes of unknown men …” Once again, few veterans were in attendance. Those who were present generally expressed disappointment. “President Wilson failed to stir the heart of the veterans,” observed one reporter. “Not once was he interrupted by a handclap or a cheer.” Wilson departed after spending a mere 45 minutes on site. At least Wilson made an appearance. Former President Taft and Chief Justice White reneged on their invitations.

After this final oration, the veterans began to pack their bags, leave their tents, and start for home. They carried away an assortment of souvenirs. Conspicuously absent were instruments of death — bullets, bayonets, or swords. The old soldiers’ most cherished keepsakes were things that were living, or had once been alive. One man saved a pine sapling. Another held a branch from a tree that had shielded him in the battle. J.C. McMasters took wheat from the fields back to his Indiana home. A surgeon from New Orleans pocketed some oak leaves from the Copse of Trees, the iconic epicenter of fighting on the battle’s final day. Many leaned on walking sticks harvested from the groves, a support to them in multiple ways. At least one veteran lugged away a suitcase full of soil from the site where he had fought. “I shall make a garden box of it,” he reportedly said.

Men like Wilson and Garrison ambled back to Washington, declaring the reunion a lesson in selfless sacrifice for the nation’s youth, but hardly mentioning the event ever again. In contrast, the veterans remembered this last, great gathering for the rest of their lives, because it gave them a chance to tell their own stories, make their own music, and remember their own history — virtually none of which would appear in the official narratives.

Thomas Flagel is an associate professor of history at Columbia State Community College in Franklin, Tennessee, and the author of War, Memory, and the 1913 Gettysburg Reunion.

This article originally appeared at Zocalo Public Square. It is featured in the July/August 2020 issue of The Saturday Evening Post. Subscribe to the magazine for more art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

Featured image: Shared history: An estimated 50,000 veterans gathered in Gettysburg in 1913 to commemorate their roles in the bloodiest battle ever fought on American soil. As one soldier said at the time, “Those who were not there can form no idea of it.” (Library of Congress)

How the Lost Cause Myth Led to Confederate “Monument Fever”

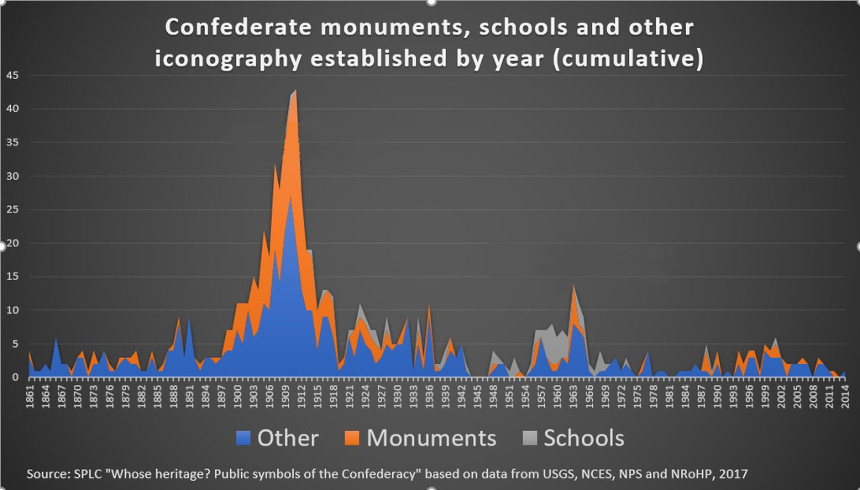

Most Confederate monuments in the U.S. were not erected by the Civil War generation to honor their dead. Instead, they were built almost two generations later. What was the cause of this “Monument Fever” that bloomed in the early 1900s, long after the end of the war?

Few Confederate monuments appeared in the South in the years following the war because of the poverty that the war had brought and the reluctance of southerners to put up statues honoring Confederate heroes while federal troops were still stationed in their states.

Southerners of the late 1860s were more concerned with their personal losses, tending the graves of loved ones and struggling to put their own lives back together. In time, though, the economy revived and more southerners could afford monuments that recalled the Confederate dead and their cause.

In 1894, Caroline Meriwether Goodlett and Anna Davenport Raines founded what would become the United Daughters of the Confederacy. They wanted a group that would tell of the Confederacy’s “glorious fight” and keep the memory of its soldiers alive. The UDC denied that it promoted white supremacy, but it strongly supported the memory of the original Ku Klux Klan and actively supported its revival. As late as 2018, the Daughters’ website declared “slaves for the most part, were faithful and devoted. Most slaves were usually ready and willing to serve their masters.”

Eighteen-ninety-four was a year where the reassuring past seemed to be fading away. The country was in a deep recession. Organized labor was staging strikes in major industries. Disruptive technology, in the form of the telephone, was heralding unexpected change. The Civil War was falling out of living memory; many of its famous veterans had already died. Older southerners were concerned the next generation would only know of the war what they learned from the unsympathetic accounts in northern schoolbooks.

The United Daughters wanted to preserve a history that centered on “The Lost Cause”: an interpretation of the war that gave a nobility to the Confederacy’s cause and its defeat.

The Cause involved far more than defending the property rights of slave holders. The South, it asserted, was defending its culture against the North’s influence — a defense of Christianity, social order, and states’ rights.

The Lost Cause emphasized the stories of noble, chivalrous warriors — the type of people who belong on a pedestal. It presented the antebellum South as a land of gracious, cultured living. And it opposed anything that would upset the traditional racial, political, and industrial status quo. It also kindled resentment against the North over what had been lost in the war.

But the narrative of the Lost Cause omits, minimizes, or mis-remembers the most troubling aspects of the war. Professor of History of the Civil War at the University of Virginia Caroline E. Janney calls the Lost Cause as “an important example of public memory, one in which nostalgia for the Confederate past is accompanied by a collective forgetting of the horrors of slavery.”

Henry Louis Gates describes the Lost Cause as “a brilliantly executed propaganda campaign that successfully changed the narrative of the cause of the Civil War from freeing the slaves to preserving states’ rights and a people’s noble way of life.”

The Lost Cause, and the appeal to southerners’ pride, proved successful to the United Daughters of the Confederacy. Between 1900 and 1917, membership grew from 17,000 to 100,000. The Daughters sought to raise awareness of the Lost Cause and to preserve southern virtues by choosing textbooks for schools that best represented their version of the Civil War. But their chief focus was on the construction of Confederate monuments.

In 1907, Goodlett told the United Daughters that, in hindsight, she’d envisioned something for the organization beyond raising statues and funding memorials. She had waited for “the monument fever to abate” so the organization could take on a more important goal. The greatest monument the Daughters could build in the South, she added, “would be an educated motherhood.” But the year that Goodlett made her comments, monument fever was an all-time high and wouldn’t slow for another decade.

Today, about 700 monuments honoring the Confederacy, its soldiers and its statesmen, can be found in 31 states and D.C., though the Confederacy only incorporated 11 states. Given when almost all were built, they are not so much memorials of the 1860s as tributes of the twentieth century to honor a version of southern history that’s goal was to, as Mayor Landrieu put it, “rewrite history to hide the truth, which is that the Confederacy was on the wrong side of humanity.”

Featured image: Statue of Robert E. Lee is removed from its pedestal on May 17, 2017 (Abdazizar, Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license, Wikimedia Commons)

Considering History: Reunion, Juneteenth and the Meaning of the Civil War

This series by American studies professor Ben Railton explores the connections between America’s past and present.

This past weekend, after Alabama Senator Doug Jones voted for a bipartisan amendment to the annual defense authorization bill that would remove the names of Confederate officers from U.S. military installations, former Attorney General and current Senate candidate Jeff Sessions tweeted an extended critique of Jones. Arguing that “Naming U.S. bases for those who fought for the South was seen as an act of respect and reconciliation towards those who were called to duty by the States,” Sessions attacked Jones’s vote as “a profound deficit in his understanding of what it means to be AL’s Senator. [Jones] seeks to erase AL’s & America’s history and thousands of Alabamians for doing what they considered to be their duty at the time.”

That Sessions, who in the late 1980s was denied a federal judgeship due to his overtly racist views and whose full name is Jefferson Beauregard Sessions III, would endorse keeping Confederate names is no surprise. But his comments reflect more widespread and fundamental American issues, not simply the prevalence of Confederate names and memorials but also the way our collective memories have consistently framed the Civil War as a tragic conflict between white Americans — rather than as the culminating moment in the history of American slavery and a complex but crucial turning point in African-American history.

In two of my recent Considering History columns, I’ve discussed the rise and dominance of neo-Confederate narratives in the century after the Civil War: tracing the late 19th century renaming and reframing of Decoration Day as Memorial Day; and using white supremacist elements of the New Deal to illustrate the decades-long process by which, as Heather Cox Richardson has recently put it, the South won the Civil War. The proliferation of Confederate memorials and statues offers one particularly overt and potent example of that trend, which is why historian Adam Domby focuses at length on such commemorations in the opening chapter of his excellent new book The False Cause: Fraud, Fabrication, and White Supremacy in Confederate Memory (2020).

Yet alongside that evolving late 19th and early 20th century neo-Confederate narrative we find another, and in some key ways even more destructive, collective vision of the Civil War: one that defines it as a tragic conflict between white Americans. Despite the central role of slavery in the war’s causes and emancipation in its turning points and outcomes, this vision focuses on the white soldiers who fought and died on both sides, as well as on the white families and communities torn apart by the war. Minimizing both the hundreds of thousands of African-American soldiers who served the Union cause and the millions of African Americans profoundly affected by its victory, this narrative instead frames the war’s shared losses and tragedies for all white Americans. And in so doing, this longstanding definition of the war’s meanings likewise, and even more crucially, contributes to an understanding that the nation’s primary goal in the post-war period was to bring white America together once more, rather than to address the significance and aftermaths of emancipation for enslaved African Americans.

In the famous closing sentence of his March 1865 Second Inaugural Address, with the war not yet concluded, President Abraham Lincoln provided a clear early example of that vision:

With malice toward none, with charity for all, with firmness in the right as God gives us to see the right, let us strive on to finish the work we are in, to bind up the nation’s wounds, to care for him who shall have borne the battle and for his widow and his orphan, to do all which may achieve and cherish a just and lasting peace among ourselves and with all nations.

While Lincoln reiterated that the Union cause was right, both this sentence and his brief speech overall focus far more on the goals of healing and peace, and on the absence of malice and presence of charity toward the Confederates that could best achieve those goals.

Those post-war goals came to be part of an overarching frame of reunion, the process of bringing back together the nation that had been tragically and painfully divided by the war. So widespread were cultural depictions of that process that an entire literary genre, what scholar Nina Silber has termed “the romance of reunion,” developed in the post-war decades; these works feature Northern and Southern protagonists whose post-war romantic relationships, connections which depend in these stories on the characters downplaying the war’s horrors in favor of mutual understanding and admiration, symbolize and model the reuniting of North and South.

This frame for the post-war period as a time of reunion also entailed a particular vision of the war itself. That narrative focused on the concept of “disunion,” on the war as fundamentally defined by the tragic separation of and ultimately the connections between the Union and Confederate sides. As historian David Blight argues in his landmark study Race and Reunion: The Civil War in American Memory (2002), this “culture of reunion … emphasized the heroics of a battle between noble men of the Blue and the Gray.” We see the legacy of that emphasis in Jeff Sessions’ argument for “respect and reconciliation towards those who were called to duty by the States,” Confederate as well as Union.

This vision of heroism and sacrifice on both sides has come to dominate cultural representations of the Civil War. Michael Shaara’s best-selling and Pulitzer-winning historical novel The Killer Angels (1974), adapted into the popular Hollywood film Gettysburg (1993), depicts the humanity and heroism of Union and Confederate officers at the pivotal Battle of Gettysburg. Even more influential has been Ken Burns’ nine-part documentary The Civil War (1990), the centerpiece of which is the use of private letters and diaries to depict the perspectives and voices of ordinary soldiers on both sides of the conflict. These and other texts have helped create and amplify an enduring narrative of brother fighting brother, of two divided yet parallel American communities.

Yet more than 180,000 of the Union soldiers were African American, of course, a sizeable cohort (comprising 10 percent of the Union army and 25 percent of its navy) all too often forgotten in these collective memories of the war. But the bigger problem with this vision of the Civil War is that it has minimized, if not indeed ignored, what Blight calls “the moral crusades over slavery that ignited the war … and the promise of emancipation that emerged from the war.” Which is to say, our collective memories of a war can focus not only on the experience of fighting it, but also and especially on the war’s overarching purposes and meanings — hence our narratives of World War II, for example, as a battle to halt Nazi aggression and stop the Holocaust. What would it mean to define the Civil War not as a tragic conflict between divided Northern and Southern states, but as a necessary and crucial final step in the long, even more tragic history of slavery in America?

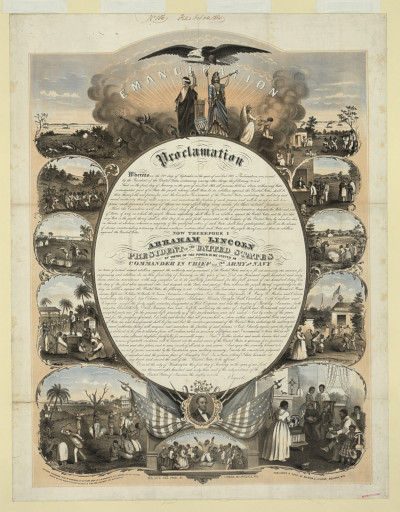

One thing that reframing would mean is that the abolition of slavery would become not just an element or effect of the Civil War, but the war’s essential through-line and meaning. On June 19th, 1865, a community of enslaved African Americans in Texas learned that the war was over and slavery had been abolished; that date has been known ever since as Juneteenth, a symbolic anniversary of emancipation celebrated as a holiday within the African-American community. But over the more than 150 years since, Juneteenth has never received any national or formal recognition as a holiday, much less been highlighted as symbolizing the war’s culminating and crucial event. Similarly, the 1863 events consistently emphasized by historians and in our collective memories as the turning points in the war are the early July Battles of Gettysburg and Vicksburg, not the January 1 Emancipation Proclamation that represented the first step toward comprehensive abolition.

If the Civil War had been consistently defined in the immediate post-war period through this narrative of slavery and emancipation, it would have likely been more difficult for the nation to so thoroughly forget and fail its African-American citizens. An 1877 editorial in the progressive magazine The Nation opined that, with the end of Reconstruction, “the negro will disappear from the field of national politics. Henceforth the nation, as a nation, will have nothing more to do with him.” Such an argument depended on the narratives of disunion and reunion, on a vision of both the war and the post-war period that emphasized white Americans coming back together after a tragic separation, rather than African Americans participating in and emerging out of a war of emancipation and abolition.

We can’t change what happened after the Civil War, nor the events of the subsequent 150 years. But we can shift both our narratives of those events and our 21st century conversations about the war. And if we remember the war as both the culmination of the tragic history of slavery and a fraught but crucial turning point toward all that has followed for African Americans, if we commemorate emancipation as the war’s fundamental purpose and Juneteenth as its defining memorial, we will be able not only to reframe the Civil War’s essential meanings, but also to move away from the narratives that have made collective Confederate memory so possible and potent.

Featured image: African Americans celebrating Juneteenth in 1900 (The Portal to Texas History Austin History Center, Austin Public Library)

Considering History: The Lessons of Memorial Day’s Decoration Day Origins

This series by American studies professor Ben Railton explores the connections between America’s past and present.

As is the case with too many American holidays, the meaning of Memorial Day has gradually evolved away from its more serious themes and toward more frivolous details: the start of summer (and the summer blockbuster season), a long weekend, barbeques and pool openings, sales. While all our national holidays would benefit from a return to their focal subjects and commemorations, it seems particularly important that we do so with a holiday dedicated to the memory of those American men and women who have sacrificed their lives in our military conflicts and wars across the centuries.

Yet there is an additional layer to Memorial Day’s forgotten histories: the holiday’s origins, in the immediate aftermath of the Civil War, as Decoration Day. And better remembering Decoration Day does not simply help us further contextualize our contemporary Memorial Day celebrations — it illustrates some of the worst and the best of Reconstruction, race, and American history and identity.

Decoration Day’s precise historical origins remain somewhat uncertain and debated, but historian David Blight has convincingly traced them to a specific community and post-war moment: formerly enslaved African Americans in Charleston, South Carolina placing flowers on the graves of Union Army soldiers in May 1865 (less than a month after the Civil War’s conclusion). As Blight has argued, from this striking singular moment, a wider tradition arose over the next few years, with both African Americans and others decorating soldiers’ graves throughout the nation’s many Civil War cemeteries.

One of the clearest representations of this evolving Decoration Day tradition can be found in a short story, Constance Fenimore Woolson’s “Rodman the Keeper” (1880). Woolson’s titular protagonist is a Union veteran working at a Civil War cemetery in an unnamed Southern state, “keeping” the graves of Union and Confederate casualties alike. The story as a whole traces his complex relationship to a dying Southern veteran and the veteran’s bitter daughter, but at its heart is Rodman’s observation of a group of African Americans decorating Union graves. “One morning in May,” Woolson writes, “the [town’s] whole population of black faces went out to the national cemetery with their flowers on the day when, throughout the North, spring blossoms were laid on the graves of the soldiers.”

As the phrase “throughout the North” reflects, by the late 1870s the local and somewhat informal Decoration Day tradition had begun to evolve into a formalized national commemoration, one that Woolson refers to in her text as “Memorial Day.” While that evolution partly built on the kinds of local and African American celebrations that Woolson’s story features, it also too often illustrated a more troubling national trend: the move, with the end of Reconstruction, away from memories of slavery and activism for African American rights and toward the kinds of unifying, white supremacist narratives reflected in the deification of Robert E. Lee.

A May 1877 speech in New York City exemplifies that national shift. For many years the Brooklyn Academy of Music (BAM) had presented a Decoration Day speech, generally featuring Union veterans and former abolitionists. But in 1877, BAM invited instead Roger A. Pryor, a former Confederate general who had moved to the city after the war and become a prominent Democratic politician and opponent of Reconstruction. Pryor’s Decoration Day address offered that perspective on recent American history, calling Reconstruction a “dismal period … devised to balk the ambition of the white race.” Yet he also sought to revise his audience’s understanding of “the cause of secession,” and in so doing to contribute to the national shift away from memories of slavery and race and toward the Confederate sympathies of the developing Lost Cause narrative.

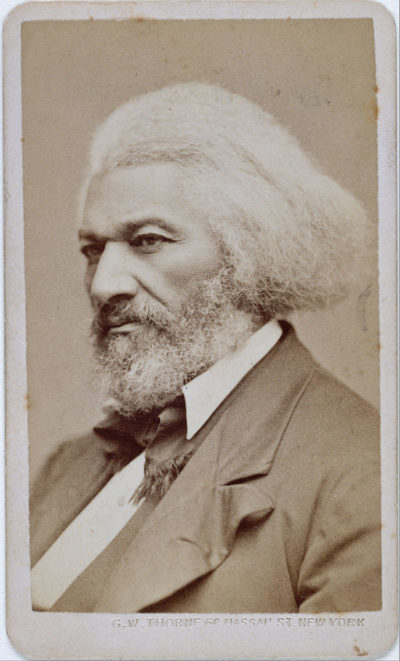

Such shifts likewise changed the meaning of Decoration (and subsequently Memorial) Day, away from African American commemorations of the Civil War and abolition and toward a broader and more conciliatory emphasis on white soldiers and heroism from both sides of the conflict. Yet that narrative was not and is not the only way to remember and celebrate the holiday and its meanings, and in his May 30, 1871 Decoration Day address at Virginia’s Arlington National Cemetery, Frederick Douglass offered a distinct, impassioned, and inspiring rejoinder to such revisionist histories and argument for the holiday’s vital national significance.

In his short speech, entitled “The Unknown Loyal Dead,” Douglass seeks to honor “the solemn rites of this hour and place,” to give voice to the cemetery’s “silent, subtle and all-pervading eloquence, far more touching, impressive, and thrilling than living lips have ever uttered.” He notes that, “We are sometimes asked, in the name of patriotism, to forget the merits of this fearful struggle, and to remember with equal admiration those who struck at the nation’s life and those who struck to save it, those who fought for slavery and those who fought for liberty and justice.” And he offers a potent challenge to that perspective and reminder of the war’s (and thus the holiday’s) central subjects, concluding,

But we are not here to applaud manly courage, save as it has been displayed in a noble cause. We must never forget that victory to the rebellion meant death to the republic. We must never forget that the loyal soldiers who rest beneath this sod flung themselves between the nation and the nation’s destroyers. If today we have a country not boiling in an agony of blood, … if now we have a united country, no longer cursed by the hell-black system of human bondage, if the American name is no longer a by-word and a hissing to a mocking earth, if the star-spangled banner floats only over free American citizens in every quarter of the land, and our country has before it a long and glorious career of justice, liberty, and civilization, we are indebted to the unselfish devotion of the noble army who rest in these honored graves all around us.

Memorial Day represents an opportunity to remember all those American soldiers who have given their lives for their country. Yet there is a particular significance to remembering not just this group of Civil War soldiers, but also and especially the holiday that first commemorated them and the American community that initiated that holiday. If the shift away from Decoration Day too often reflected a frustrating abandonment of that community, we can return to those crucial American histories by better remembering Memorial Day’s origins.

Featured image: A 1883 political cartoon by Bernhard Gillam shows politicians and others in a cemetery on Memorial Day, each seeming to mourn at gravestones bearing the names of their political losses. (Library of Congress)

Considering History: The New Deal, White Supremacy, and How the South Won the Civil War

This series by American studies professor Ben Railton explores the connections between America’s past and present.

On April 9th, 1865, just under four years after the Civil War’s opening salvo at Fort Sumter, Confederate General Robert E. Lee surrendered to Union General Ulysses S. Grant at Virginia’s Appomattox Court House, formally ending that divisive and destructive national conflict (although some Confederates refused to surrender for months thereafter). The attempt by 11 Southern states and a few Western territories to create a distinct nation organized around founding principles of slavery and white supremacy, the Confederate States of America (CSA), had failed, and the United States was reconstituted as a unified nation once more.

Yet over the next half-century, as I’ve written about for this column and elsewhere, a neo-Confederate perspective on American history and identity came to dominate the national landscape. A vital new book, historian Heather Cox Richardson’s How the South Won the Civil War: Oligarchy, Democracy, and the Continuing Fight for the Soul of America, links that trend to the development of and battles over the post-Civil War American West. But by the early 20th century a neo-Confederate, white supremacist narrative likewise dominated national politics and policy, as another of this week’s historical anniversaries can help us remember.

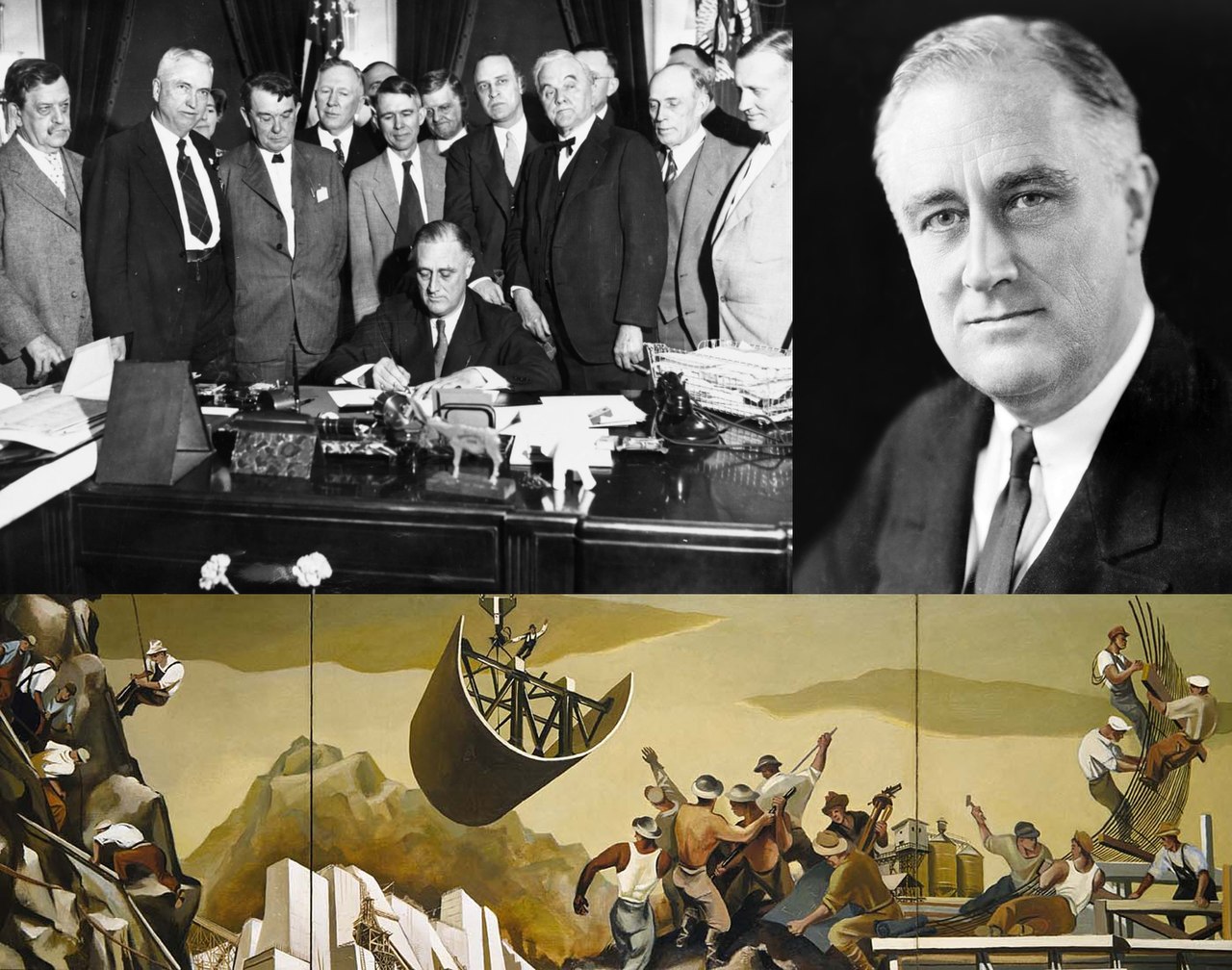

On April 8th, 1935, President Franklin D. Roosevelt introduced the Emergency Relief Appropriation Act, a request to Congress for $4.88 billion to create and support a number of public works programs within the overarching frame of the era’s evolving New Deal responses to the Great Depression. Although the Act’s targeted unemployment relief was controversial and much of it was eventually never allocated, the Act did lead directly to the creation of many of the New Deal’s most famous and successful public works programs, including the Works Progress Administration (WPA) and its subsidiaries such as the Federal Art Project and the Federal Theatre Project, the National Youth Administration, and the Rural Electrification Administration.

Yet the New Deal’s programs, like the Roosevelt Administration overall, consistently gave in to the demands of Southern white supremacists and discriminated against African Americans (and other Americans of color) in a number of distinct yet interconnected ways. Many of those Southern white supremacists were Democratic Congressmen whose votes Roosevelt was courting to secure passage of the New Deal, a political reality for the Democratic Party in this early 20th century period (before the party realignment of the 1950s and ’60s). Yet the very fact that Roosevelt needed those Southern Congressmen’s votes reflects the political and social power of this white supremacist community in 1930s America. And the various forms taken by these New Deal racial discriminations illustrate the destructive effects of white supremacy on millions of Americans.

The most overt such discriminations were the ways in which numerous New Deal programs were crafted to either exclude entirely or limit the opportunities of African Americans. The Federal Housing Authority (FHA) excluded the African-American community overtly, refusing to guarantee mortgages for many African Americans seeking to buy homes; the Social Security Act (SSA) did so more indirectly but just as potently, excluding agricultural and domestic workers (two categories in which the majority of African Americans and many other Americans of color worked) from its protections. Other programs discriminated by creating segregated and unequal structures that mirrored Jim Crow systems: the National Recovery Administration (NRA) offered white Americans the first opportunity at its jobs, and paid African American workers substantially less; the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) maintained segregated and significantly less well-maintained camps for African Americans.

The exclusion of agricultural workers from the SSA was paralleled and extended by another, perhaps unintended but still hugely destructive form of discrimination, one exemplified by the Agricultural Adjustment Administration (AAA). As created by the 1933 Agricultural Adjustment Act, the AAA offered farmers subsidies in exchange for limiting their production, a policy intended to limit overproduction and help raise prices. But since many African-American farmers worked as sharecroppers, a system that developed alongside the re-emergence of Southern white supremacy in the late 19th century (part of what historian Douglas Blackmon has called “slavery by another name”), it was their white landlords who received the subsidies, and the farmers who were unable to produce and earn from their crops. The AAA thus pushed more than 100,000 African-American farmers off their land in 1933 and 1934 alone.

Beyond the New Deal’s programs and policies, the Roosevelt Administration likewise appeased white supremacists through its inaction on and even opposition to anti-discrimination laws in the period. The most prominent and ironic example was President Roosevelt’s opposition to an anti-lynching bill on which his wife Eleanor Roosevelt had collaborated with NAACP President Walter White and Congressional allies. Roosevelt told the pair in a private meeting that he could not publicly support the bill, arguing about the Southern white supremacists: “If I come out for the anti-lynching bill now, they will block every bill I ask Congress to pass the keep America from collapsing. I just can’t take the risk.” When the bill, known as the Costigan-Wagner Act, nonetheless came before Congress in February 1935, those Southern politicians threatened a lengthy filibuster, and the president remained silent; the bill died without a vote, and no federal anti-lynching legislation would ever be passed (until earlier this year, in a largely symbolic gesture).

The combined effect of all these discriminations and exclusions was that African Americans not only continued to occupy a significantly segregated and disadvantaged position in American society, but also did not receive the same benefits and opportunities from these vital programs as their peers — not during the depths of the Depression, and not over the decades since when many of those programs have continued to aid American communities. In his groundbreaking 2014 essay “The Case for Reparations,” journalist and public scholar Ta-Nehisi Coates argues that these discriminations (he particularly focuses on housing inequities such as those perpetrated by the Federal Housing Authority) have cost African-American individuals, families, and communities tens of millions of dollars across the 20th century and into the 21st, yet another profound and painful effect to the white supremacist perspective’s powerful hold on American politics and society.

Featured image: An artist’s rendering of the surrender of Confederate General Robert E. Lee to Union General Ulysses S. Grant at Appomattox Court House on April 9, 1865. (Library of Congress)

Considering History: Robert E. Lee, James Longstreet, and the Truths of Civil War Memory

This series by American studies professor Ben Railton explores the connections between America’s past and present.

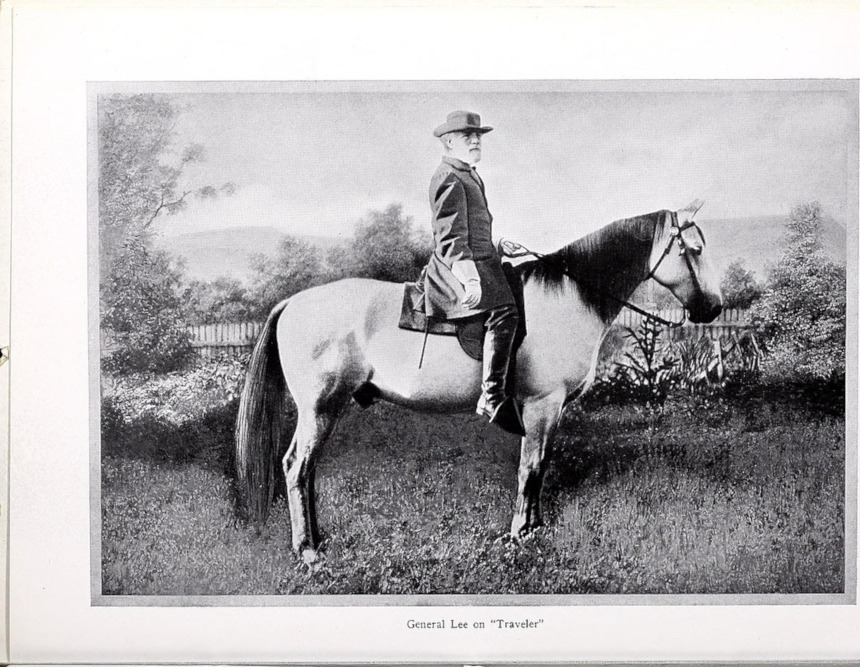

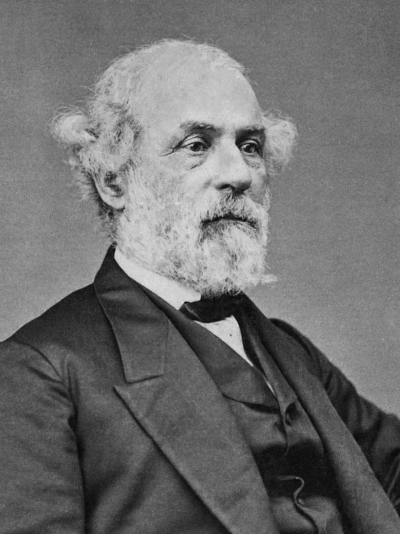

Growing up in Virginia, the Civil War was my gateway to a lifelong love of all things American history, and as a youthful Civil War buff, General Robert E. Lee was my idol. Even at a young age I certainly understood that the Confederacy had fought for a profoundly ignoble cause, and that the war’s outcome had been a just and necessary one. But I nonetheless embraced every element of the Lee mythos: the U.S. Army veteran who reluctantly joined the cause in solidarity with his home state but recognized the evils of slavery; the sensitive soul who declared (during a victory, the Battle of Fredericksburg) “It is well that war is so terrible, otherwise we should grow too fond of it”; and most of all (to a kid obsessed with military history and battle maps) the brilliant strategist who ran circles around the Union Army’s lesser military minds for much of the war.

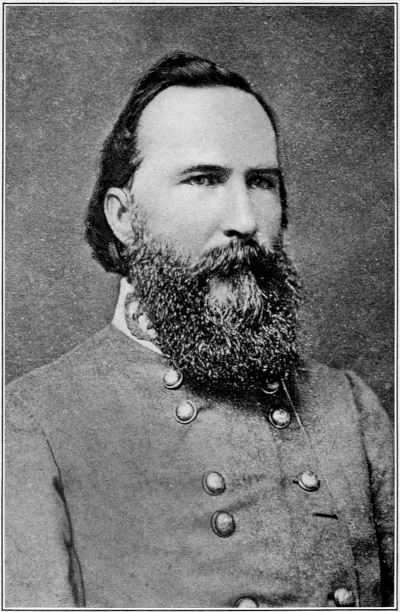

That last element in particular led me to a concurrent youthful disdain for General James Longstreet, one of Lee’s chief lieutenants throughout the war and yet a frequent dissenter from Lee’s strategies. That seemed particularly to be the case at the pivotal battle of Gettysburg, when (the story went) Longstreet’s disagreements with and deviations from Lee’s plans contributed to the Confederate loss. Yet whatever the details of that controversial military moment, the broader historical reality is both distinct and crucially telling: the deification of Lee and demonization of Longstreet reflect not military history at all, but instead the postwar and ongoing development of Civil War Memory.

Although Lee (1807-1870) was fourteen years older than Longstreet (1821-1904), the details of the two men’s careers through the Civil War are remarkably similar (and echo those of many other Civil War officers on both sides). Both graduated from West Point when they were 21 years old, both fought in the Mexican American War and received attention and acclaim for their service in that 1840s conflict, and both continued to serve the U.S. armed forces in multiple roles between that war’s conclusion and the Civil War’s outset. Both men were apparently uncertain about secession, not least because of those continued connections to the U.S. military; but both joined the Confederate Army in its first months of existence and would become two of its most prominent leaders throughout the war.

It was after the war’s end that the two men’s stories — and especially the collective perceptions and memories of them — would diverge much more fully. Lee died just a few years later, in 1870, but by then the national deification process traced in historian Thomas Lawrence Connolly’s The Marble Man: Robert E. Lee and His Image in American Society (1977) was already well underway. Those kinds of idealized tributes to Lee ramped up significantly after his death, leading Frederick Douglass to lament such “bombastic laudation” and “nauseating flatteries” to a man who “was a traitor and can be made nothing else.” But Lee was indeed made over the next few years into something quite different, the iconic hero celebrated in texts like Mississippi lawyer and author James D. Lynch’s epic poem Robert E. Lee, or, Heroes of the South (1876).

Other than Douglass, one of the few prominent late 19th century voices to resist this deification of Lee was none other than James Longstreet. In his 1896 memoir, From Manassas to Appomattox: Memoirs of the Civil War in America , Longstreet sought to set the record straight about both specific events such as the Battle of Gettysburg and the overall national celebration of Lee as the war’s unquestioned genius. After quoting Lee’s reflections on the outset of Gettysburg’s third and final day of fighting, Longstreet writes simply, “This is disingenuous,” and the phrase sums up a good deal of his critique of both Lee’s memories and the collective memories of Lee. Although he does so in the respectful tone due to his commanding officer, Longstreet consistently creates a far different and much more critical picture of Lee and the war. For example, Lee opens his account of the night before that crucial third day by claiming that “the general plan was unchanged” and “Longstreet … was ordered to attack the next morning”; Longstreet counters that Lee “did not give or send me orders,” and so “in the absence of orders,” Longstreet had to utilize his own scouts and develop his own plan for the start of the next day’s (ultimately disastrous) attacks.

It would be easy to identify those critiques as the source of the neo-Confederate vitriol directed at Longstreet in the postbellum era. But the truth is that long before he published his memoirs, Longstreet had become a target for such hatred through his post-war actions, and specifically through his embrace of African American rights during and after Reconstruction. Longstreet joined the Republican Party, endorsing his friend (and Lee’s most formidable wartime adversary) Ulysses S. Grant for President in 1868 and taking on vital Reconstruction roles such as commander of all federal and state forces in New Orleans in 1872. In that latter role he commanded armed African American troops against a white supremacist militia at the city’s 1874 Battle of Liberty Place, when more than 8,000 men of the anti-Reconstruction White League sought to challenge and overturn a Louisiana gubernatorial election.

These Reconstruction conflicts comprised battles over America’s present and future but also over Civil War memory. Longstreet likewise resisted the era’s embrace of the Lost Cause narrative and its attempts to reframe the Civil War’s causes and meanings, at one point remarking to Grant, “I never heard of any other cause of the quarrel than slavery.” Yet the Lost Cause narrative came to dominate the postwar period so much so that by 1888, author Albion Tourgée wrote that American literature and culture had become “not only southern in type, but distinctly Confederate in sympathy.” And just as those national neo-Confederate sympathies made Lee into a marble man, they made Longstreet into at best a failure and at worst a villain.

By the early 20th century, that process was complete, as reflected clearly in my hometown of Charlottesville, which in the late 1910s and early 1920s famously constructed its statues of Robert E. Lee and his now favored (and more clearly white supremacist) lieutenant, Stonewall Jackson. As I grew up in Charlottesville half a century later, it’s no wonder that this marble tribute to Lee helped cement his iconic status in my youthful Civil War Memory, and helped push Longstreet further to the fringes. Whatever happens to those two statues or any of the other Confederate memorials around the country, it’s long past time we collectively revisit and revise our memories of both these men and the racial and national images they symbolize.

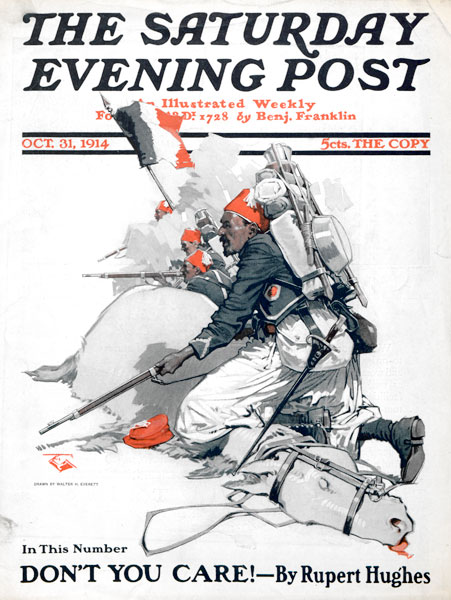

The Great War: October 31, 1914

In the October 31, 1914, issue: The Post publishes its first piece of world war fiction, a war reporter’s shares his experiences in Belgium, and a U.S. senator predicts an economic boom.

The Miller of Ostend

By Melville Davisson Post

In its first piece of World War fiction, the Post brought up a topic that would become one of the major controversies of the war: civilian atrocities.

For weeks, stories about German brutalities against Belgians had been circulating in the media. The stories would become more violent and more numerous as the war settled into a frustrating stalemate. And when the U.S. entered the war, the stories would be revived and embellished to build American support for the war.

Did they actually occur? Did German soldiers really butcher helpless Belgians? What about the story of Germans cutting off the hands of Belgian children?

Were Germans murdered in their sleep or poisoned by the people of Belgium, or ambushed by isolated squads of partisans? In this story, an elderly miller exacts vengeance for a granddaughter killed in a German air attack.

It’s a brutal little story unlike the polite fiction usually run by the Post. But it’s possible the editors chose it out of sympathy for inoffensive Belgium or out of a desire to see Germany punished for violating this neutral country.

Melville Post (no relation) continued to write after the war and, in time, became an early and influential author of mystery stories.

“Presently, far away toward Brussels, a thing like a wingless goose appeared in the sky. It traveled at great speed and soon took form and outline. It came on like a projectile toward Ostend. One could distinguish now its long aluminum cylinder and the strange equipment of the Zeppelin, all painted gray like a warship.

“There was a long, dull roar, and the glass-enclosed terrace of the Kursaal that bowed out toward the promenade of Leopold south along the Digue de Mer flew into a cloud of dust and broken tiles.

“Meanwhile, as though signaled of the approach of the Zeppelin, an English submarine arose like some fabled sea-thing out of the slime of the harbor. A figure emerged from the turret, seized a lever, and a gun that was folded into the back of the monster swung up into place, other figures appeared, and the gun lifting perpendicular opened fire on the dirigible. …

“Finally the Zeppelin, driving dead away toward Brussels, was seen suddenly to list. It hung for a moment half balanced over, then it glided slowly down. A shot traveling parallel with the cylinder had ripped open the gas compartments along the whole side. …

“It did not fall — the gas chambers on the other side of the long aluminum envelope were enough to prevent that, but not enough to hold it in the air, and listing heavily it descended slowly into the fields. The detachment of Belgian cavalry riding the Brussels road raced toward it.

“At the dull boom of the first explosion the old miller, sitting on his door step, arose and started to return to Ostend. … He knew the city, and the direction of the sound located for him where the deadly thing had struck.

“His awful fear was justified. Under the wrecked glass of the Kursaal, among the scattered cots and the wounded—now mangled dead men—a little broken thing, with a red cross stitched to her sleeve and the sun still nestling in her hair, lay motionless across the sill of a door.”

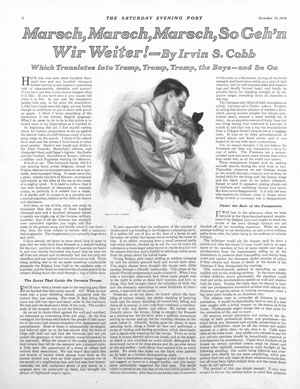

Marsch, Marsch, Marsch, So Geh’n Wir Weiter

(the German translation of the American Civil War song lyric “Tramp, tramp, tramp, the boys are marching”)

By Irvin S. Cobb

Cobb reported he’d seen none of the atrocities that others had reported in Belgium. But in this installment, he sees several examples of the German’s stern military justice.

The German army developed a harsh attitude toward the Belgians. They had originally expected Belgium would permit them to march through the country to invade France. They were surprised, then angered, when the Belgians not only refused German demands to pass through, but resisted their advance with force.

The first stories of atrocities, it seems, came from the Germans, who reported that Belgian civilians were waging a guerilla war, ambushing prisoners and sabotaging equipment. As Cobb reports, German officers believed these stories and used them as justification for executing people they considered dangerous to their army. The colonel who kept him under guard told Cobb he could not cross the front lines to reach Brussels for fear of what his own men might do.

“‘For your own sakes … I dare not let you gentlemen go. Terrible things have happened. Last night a colonel of infantry was murdered while he was asleep; and I have just heard that fifteen of our soldiers had their throats cut, also as they slept. From houses our troops have been fired on, and between here and Brussels there has been much of this guerilla warfare on us. To those who do such things and to those who protect them we show no mercy. We shoot them on the spot and burn their houses to the ground.

“‘We make no attempt to disguise our methods of reprisal. We are willing for the world to know it; and it is

not because I wish to cover up or hide any of our actions from your eyes, and from the eyes of the American people, that I am refusing you passes for your return to Brussels today. But, you see, our men have been terribly excited by these crimes of the Belgian populace, and in their excitement they might make serious mistakes.’

“On the second morning of our enforced stay … we watched a double file of soldiers going through a street. … Two roughly clad natives walked between the lines of bared bayonets. One was an old man who walked proudly with his head erect. The other was bent almost double, and his hands were tied behind his back.

“A few minutes afterward a barred yellow van, under escort, came through the square fronting the railroad station and disappeared behind a mass of low buildings. From that direction we presently heard shots. Soon the van came back, unescorted this time; and behind it came Belgians with Red Cross arm badges, bearing on their shoulders two litters on which were still figures covered with blankets, so that only the stockinged feet showed.

“Along toward five o’clock a goodish string of cars was added to our train, and into these additional cars seven hundred French soldiers, who had been collected at Gembloux, were loaded. With the Frenchmen as they marched under our window went, perhaps, twenty civilian prisoners, including two priests and three or four subdued little men who looked as though they might be civic dignitaries of some small Belgian town. In the squad was one big, broad-shouldered peasant in a blouse, whose arms were roped back at the elbows with a thick cord.

“‘Do you see that man?’ said one of our guards excitedly, and he pointed at the pinioned man. ‘He is a grave robber. He has been digging up dead Germans to rob the bodies. They tell me that, when they caught him, he had in his pockets ten dead men’s fingers which he had cut off with a knife because the flesh was so swollen he could not slip the rings off. He will be shot, that fellow.’

“We looked with a deeper interest then at the man whose arms were bound, but privately we permitted ourselves to be skeptical regarding the details of his alleged ghoulishness. We had begun to discount German stories of Belgian atrocities and Belgian stories of German atrocities. I might add that I am still discounting both varieties. I hear of them daily, almost hourly, but usually the proof is lacking.”

Permanent Prosperity

By Albert J. Beveridge

Not only did former U.S. Indiana Senator Beveridge (R) expect the war would bring an economic boom to the United States, he thought it could last even beyond the war. But it would require the government keeping politics out of its economic policy.

“Every day we hear of the great material prosperity the present world war will bring us. … We are adjured to lament this tragedy of the nations and to pray for its ending, nevertheless we are advised to make the most of the situation and to fill our pockets while we can, and as full as we can.

“Without any foreign war, and purely from our natural advantages, handled in a common-sense manner, we ought to have a much greater prosperity in the United States than we ever have had. … Why, then, is this not the case? … Partisan politics.

“[It] turns the crank, which runs the endless chain of tariff ups and tariff downs; of business fever and business chill; of a diseased prosperity and a diseased depression. Thus it is that tariff earthquakes periodically shake and shatter American business. Thus it is that we have not and never have had steady and normal business conditions. Thus it is that such a thing as permanent prosperity is unknown in America. And steady normal business and permanent prosperity never can be had so long as we allow partisan politicians to make our tariff the football of partisan politics.”

Step into 1914 with a peek at these pages from The Saturday Evening Post 100 years ago.

American Civil War Atrocity: The Andersonville Prison Camp

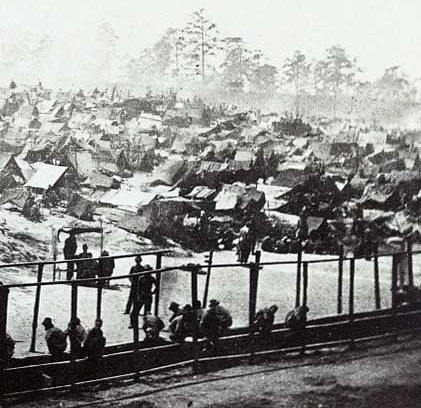

Of the 45,000 Union soldiers who’d been held at Andersonville Confederate prison during the American Civil War, 13,000 died. During the worst months, 100 men died each day from malnutrition, exposure to the elements, and communicable disease.

Restoring unity in America after the Civil War was never going to be easy. Too many Americans felt they could never forgive wrongs committed by the enemy during the conflict. Southerners could point to the destruction wrought by General Sherman’s army on its destructive march through Georgia and South Carolina. And Northerners could point to Andersonville.

This Confederate prisoner-of-war camp, which opened 150 years ago this week, was built in southeast Georgia to hold the Union prisoners who could no longer fit into Virginia’s prison camps.

Its stockade, in which prisoners were detained, measured 1,600 feet by 780 feet, and was designed to hold a maximum of 10,000 prisoners.

The prisoners arrived before the barracks were built and so lived with virtually no protection from the blistering Georgia sun or the long winter rains. Food rations were a small portion of raw corn or meat, which was often eaten uncooked because there was almost no wood for fires. The only water supply was a stream that first trickled through a Confederate army camp, then pooled to form a swamp inside the stockade. It provided the only source of water for drinking, bathing, cooking, and sewage. Under such unsanitary conditions, it wasn’t surprising when soldiers began dying in staggering numbers. The situation worsened as the camp became overcrowded. Within a few months, the population grew beyond the specified maximum of 10,000 to 32,000 prisoners.

After 15 months of operation, the camp was liberated in May of 1865. Of the 45,000 soldiers who’d been held at Andersonville, 13,000 died. During the worst months, over 100 men died each day.

News of the conditions at Andersonville came slowly to the North. The name wasn’t even mentioned in the Post until the following March, when the notices on page 7 announced the death of Robert Price “at Andersonville, Ga.…of chronic diarrhea.” A member of the 118th Pennsylvania Volunteers, he “was taken prisoner by the rebels, May l5th, 1864” and managed to survive just three months in the camp.

As news of the death camp reached the newspapers, Northerners were newly enraged at the South and its army. Hearing of the miserable conditions and high death rate in the camp, Walt Whitman wrote, “There are deeds, crimes that may be forgiven, but this is not among them.”

Andersonville’s reputation was widely known when its name next appeared in the Post. In 1865, the Post’s front page featured a poem by Miss Phila H. Case, “In the Prison at Andersonville.” In this sentimental ballad, a narrator and his brother Ned are captured and shipped to Andersonville, where the brother soon sickens.

“He faded day by day—a prayer

Upon his lips for one sweet breath—

What wonder when the reeking air

Was chill and dank with dews of death.

But why delay my tale—he died

And careless hands bore him away,

For what was one when, side by side,

Hundreds were dying every day?”

In July, 1865, the Post reported “the former Rebel commandant [Jeff Davis] of the Andersonville prison is to be put on trial at Washington this week before a court-martial.” It adds no further comment, but an item just a few lines lower on the page reflects the bitterness many in the North were feeling. “Jeff Davis is reported, by the latest advices from Fortress Monroe, in the best of health and spirits.”

Many Northerners had expected the Federal government would hang the president of the Confederacy once he was caught after the war. But Davis, though indicted for treason, was never brought to trial. At the time the Post item above appeared, he was, in fact, living in leg irons and gravely ill. At the end of two years, the federal government released Davis on a bail of $100,000. The money was donated by Southern supporters as well as former Northern adversaries.

Andersonville’s commandant, Major Henry Wirz, didn’t fare quite as well. He was brought before a military tribunal in August of 1865 and charged with actions intended “to injure the health and destroy the lives of soldiers in the military service of the United States.” The court also charged him with murder “in violation of the laws and customs of war.”

There was no doubt Wirz allowed thousands of Union prisoners to die from exposure and malnutrition. Hundreds of ex-prisoners testified to his brutal punishments. But his defenders, both then and now, have offered several arguments in Wirz’s defense.

The federal government was partly to blame, they said, because it had halted its prisoner-exchange program.

By 1864, the Union army no longer believed it would win the war by a decisive strategic victory on the battlefield. It would have to win by attrition; that is, by wearing down the number of Confederate soldiers by death or capture until the Southern army could no longer fight. This strategy could work because the North had a greater population, and could replace the soldiers it lost, which the South couldn’t.

But the attrition strategy only worked if the Union refused to let its Southern prisoners return home and back into the Confederate army. In return, it meant Union prisoners would have to wait out the war, gathering in growing numbers in Southern prisons that barely had enough resources. However, the policy put a strain on Union camps as much as on those in the South.

Defenders of Wirz also point out the standards of hospitality were low in all prisoner-of-war camps. At the Union army’s camp at Rock Island, IL, for example, 1,300 Confederate soldiers died from an outbreak of smallpox. However, the Rock Island garrison eventually built barracks and a hospital to halt the smallpox epidemic. There were no similar improvements at Andersonville, where the death rate was four times higher than at Rock Island.

Others argued that the Confederacy couldn’t provide for its prisoners because it could barely provide for itself. The South was plagued by shortages because of the Union navy’s blockade of its coast, and the exorbitant costs of supporting its military, which left few resources for feeding or sheltering its prisoners.

These costs, however, were the unavoidable consequence of starting and continuing the war. Union soldiers had given themselves into the Confederacy’s care with the expectation of reasonable safety. Yet the soldiers who marched into Andersonville had less chance of emerging alive than the soldiers who marched onto the battlefield of Gettysburg.

The questions of guilt were troublesome. Obviously it took more than just Henry Wirz to make Andersonville possible. But once a court starts appointing guilt in wartime, it’s hard to tell where it ends.

In this case, it ended with the hanging of Major Wirz in November of 1865. The federal government was so reluctant to appoint blame that he became one of only three Confederates executed for their atrocities during the war.

Scrambling for Troops

This is the second installment of our six-part series on the lead up to Gettysburg. Click here to read part one, “The News from Gettysburg: A Hazardous Move.”

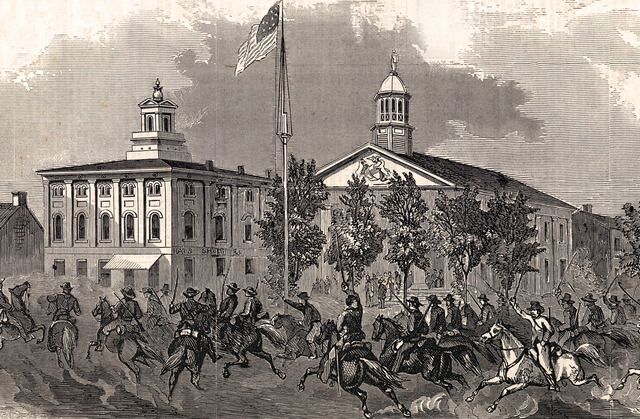

The news reached Philadelphia on a bright June morning in 1863; Gen. Robert E. Lee’s army had invaded Pennsylvania and was heading virtually unopposed to the state capitol. Suddenly, a Post correspondent wrote, the city was filled with a militant spirit.

“One could scarcely turn in any direction without meeting with a fife and drum. Recruiting officers were constantly marching up and down the streets. Large four-horse omnibuses, with bands of music and placards announcing various [assembly points], were driving about the city.

“The apathy, that for a time had seemed to taken possession of the community, was speedily dispelled. The possibility that the rebel horde might reach the Susquehanna, and even cross that stream and destroy our state capitol, was freely entertained yesterday; but there was also a firm resolve, ‘that many a banner should be torn, and many a knight to earth be borne’ before that disgraceful calamity should befall the state.”

In Harrisburg, Pennsylvania—100 miles closer to the approaching Confederate Army—the mood was quite different. There, residents had panicked after hearing that the rebel army had looted Chambersburg, Pennsylvania. Swarms of frantic passengers gathered at the railroad station, desperate to fit into any railway car they could find. The roads out of town were choked with wagons piled high with household effects, bearing families away from the enemy, and the inevitable battle.

The North’s confidence, which ran so high when the war began, was showing signs of collapse. There seemed to be little enthusiasm for fighting. The governor’s call for an emergency militia of 60,000 men was met with only 16,000 volunteers.

The Federal Army was also running low on its supply of soldiers. The eager recruits who had signed up at the war’s beginning were now approaching the end of their two-year enlistment. By the end of the month, more than 30,000 soldiers were due to leave the army. At the same time, enlistments of new recruits were falling behind goals. Men throughout the North were reluctant to sign up with an army that was so often defeated.

Faced with a drastic shortage, Congress passed the unpopular Enrollment Act, which set up the machinery for drafting 300,000 men. The Post editors disliked the idea of this conscription law, particularly its clause that allowed men to hire substitutes or buy exemptions.

Faces of the American Civil War

Photos courtesy The Library of Congress

A man who received a draft notice could hire another man to take his place in the fighting. If the substitute was found acceptable and duly sworn in, the draftee would be free of any obligation to serve, but only, the Post adds, for “the term for which he was drafted.” After the substitute had served the length of service, the original draftee would be again eligible for conscription.

If the draftee couldn’t find a substitute among poor citizens or struggling immigrants, he could simply buy a personal exemption for $300. (Congress set the amount at a level they felt would be affordable to working-class men. When you adjust that figure for 150 years of inflation, it comes close to $6,000 in 2013 money.)

Before the fighting had ended, the War Department had four separate draft calls, which drew the names of 776,000 American men. Few of these men ever saw military service. More than 20 percent never showed up. Another 60 percent were disqualified for physical or mental disability, or because they were the sole support of a motherless child, a widow, or an indigent parent.

Once sworn into service, recruits and draftees were rushed through basic training before being sent to the front. With only minimal instruction and poor leadership, a Post article claimed, it wasn’t surprising that Union troops had been repeatedly outfought by the Confederates. It quoted a Union army officer who had watched the unskilled Yankees at Chancellorsville:

“They have been taught to load and fire as rapidly as possible, three or four times a minute … they go into the business with all fury, every man vying with his neighbor as to the number of cartridges he can ram into his piece and spit out of it! The smoke arises in a minute or two so you can see nothing or where to aim. The trees in the vicinity suffer sorely, and the clouds a good deal. By-and-by, the guns get heated and won’t go off, and the cartridges begin to give out.

“Meanwhile, the enemy, lying quietly a hundred or two yards in front, crouching on the ground or behind trees … rise and advance upon us with one of their unearthly yells, as they see our fire slackens. Our boys, finding that the enemy has survived such an avalanche of fire we have as we have rolled upon them, conclude that he must be invincible, and, pretty much out of ammunition, retire.

The editors urged the army to abandon the practice of forcing men to load and fire in unison. “Accurate loading, and slow firing, at will, and only when the soldiers has an idea that his ball will tell, will do more execution than hasty loading, and rapid firing at something or nothing.”

It was well-intended advice, but would have been useless during the intense fighting at Gettysburg, where soldiers found themselves loading and firing “as rapidly as possible” simply to hold their ground.

By June 28, Lee learned the Union Army had pursued him across 120 miles in 10 days—a remarkable feat of marching at a time when 5 miles a day was a good speed for an army. He began gathering his forces for a massive blow against the Union army, which he hoped he could deliver at Gettysburg.

He couldn’t have known that a Union general, John F. Reynolds, was also hoping for a fight at Gettysburg because he’d already picked the best ground for his troops.