Highways to Heaven: The Early Interstate Promises Paradise

This article and other features about the early automobile can be found in the Post’s Special Collector’s Edition: Automobiles in America!

In this 1922 essay, the author points out that the vast changes underway to accommodate the automobile were about to vastly alter the character of towns across America, as was already happening in cities like New York and Chicago. But far from lamenting the coming changes, the writer describes them as essential to progress.

Tomorrow you may not know your own city. They have probably begun altering it already, or are planning to do so. Tomorrow your city will have wide boulevards cut through its narrow streets. These will accommodate four, six, and eight lines of traffic. They will start at the center and run miles out into the country. Thousands of buildings will be torn down. Sharp street corners will be rounded off and the circle and crescent take the place of the checkerboard.

Did your city fathers, years ago, lay out a downtown boulevard or two with a strip of parkway in the center? That beauty spot will be needed for traffic. Slums and tenements will disappear too. There will be a general grading up of living standards and an equalization of real-estate values.

When you drive a car the traffic cop will no longer be able to bawl you out, for he will disappear from street crossings, guiding traffic by electric signals from a point where he can see everything but say nothing — that is, if he doesn’t disappear altogether.

When you go for a walk it will be a far safer and more comfortable form of exercise than today, for the bulk of automobile traffic will either be transferred to elevated roads for automobiles alone, or disappear into tunnels. The trolley cars will disappear underground or be replaced by buses, which are not only more flexible than the trolley, dodging in and out of traffic, but are more flexible in routing.

Your city will be linked with others all over the state and country by great trunk motor highways, with lighted traffic signals, and perhaps traffic officers. Much of the motor travel between cities will be out of sight, on separate highways that do not enter the towns at all, but skirt them.

The automobile is at the bottom of all these changes. With the number of cars increasing to, in some cases, one for every two families, our cities have developed street traffic comparable with high blood pressure.

“Say, that thing’ll never be practical!” exclaimed a New Yorker when he first saw a horseless carriage. “Why, a man has to go ahead of it with a red flag!” Within five years he was driving an automobile himself. When horses and pedestrians became accustomed to the automobile, the man with the red flag was no longer necessary. But today he is again walking ahead, figuratively, as the traffic policeman. This is fundamentally wrong. “Speed limits on the automobile are a paradox,” says a New York trade-journal publisher. He writes: “The automobile is designed to run fast. That is its whole function, attraction, and service. Limit it, and you lose all its benefits. Speed limits and traffic control have become necessary because we have not yet learned to separate the automobile from slower traffic, and give it highways of its own.”

Few of our cities were really planned — for the most part they just happened — and even the best city plans of our fathers and grandfathers have been outgrown. The cowpath origin of city streets is familiar and amusing. People delight in its absurdities, getting lost in Boston’s old waterfront mazes, and verifying the fact that Pearl Street, in lower New York, crosses Broadway twice. A cowpath town was often most convenient for getting about, so long as everything was built within walking distance, allowing goods to be delivered by wheelbarrow. When it got larger, the cowpath section was extended on a checkerboard plan providing for growth, but usually with streets too narrow for present-day traffic, and with far too few parks and breathing places. If granddad was very farsighted he laid down a combination of checkerboard and turnpike, as in Washington and Indianapolis, the turnpikes radiating like the spokes of a wheel, providing lines of growth, and also highways by which farmers could bring in food from the surrounding country.

In general there are only these three kinds of towns, cowpath, checkerboard, and cartwheel. A cowpath town tends to congestion at the center rather than healthy growth at the radius, and makes dandy slums. The checkerboard town grows faster. The cartwheel town grows fastest of all, and most evenly and healthily.

Today we have better information than previous generations upon which to plan cities for the future. But we are dealing with city difficulties piecemeal. When traffic begins to tangle at a certain corner, we put a policeman at that corner to straighten traffic out. The tangle spreads up and down as traffic grows. We put more policemen on more corners, then lift them into towers and organize control in units of five or 10 blocks. But mere streets become impossible for handling all the traffic. Street cars, automobiles, motor trucks, horse vehicles, and pedestrians must be separated and given their own right-of-way where none can hamper or endanger the others.

—“Your Town Tomorrow,”

The Saturday Evening Post, April 1, 1922

Henry Ford’s Grandson Defends the Car

This article and other features about the early automobile can be found in the Post’s Special Collector’s Edition: Automobiles in America!

Scion of the famous automobile family, Henry Ford II wrote this Post article in 1976 at the height of the energy crisis. In a time of oil shortages, long gas lines, and worries about U.S. dependence on the oil-producing nations of the Middle East, Ford defends the car and his grandfather’s legacy.

It was just 70 years ago that my grandfather, Henry Ford, wrote a letter to a magazine called The Automobile describing his plans to build 20,000 runabouts the following year. One purpose of the letter was to answer the many skeptics who saw the automobile only as a fad. He wrote: “The assertion has often been made that it would be only a question of a few years before the automobile industry would go the way the bicycle went. I think this is in no way a fair comparison and that the automobile, while it may have been a luxury when first put out, is now one of the absolute necessities of our later-day civilization.”

That letter was written when the car was still something of a curiosity. It had not yet gone into mass production. There was no highway system worthy of the name. The relatively few cars on the roads were mostly in the hands of people of means. There were millions of people in the country who had never seen an automobile, and many towns and villages where none had ever appeared.

But it was in that same year, 1906, that the automobile proved to be the absolute necessity that my grandfather had called it. When the San Francisco earthquake struck, the 200 private automobiles in the city were immediately pressed into service, transporting the injured to hospitals, moving police from one part of the stricken city to another, and helping out in a variety of ways. When it was all over, the San Francisco Chronicle observed: “Men high in official service … say that, but for the auto, it would not have been possible to save even a portion of the city or to take care of the sick or to preserve a semblance of law and order.”

I recall my grandfather’s letter and the role cars played in the San Francisco earthquake only to provide some historical perspective. In order to look at the future of the automobile with any degree of objectivity, I believe you have to remember that the automobile has always had its share of critics. It has them today and it will certainly continue to have them in the future.

In the early part of the century, the critics of the car would see one stalled at the side of the road, laugh at the hapless driver and tell him — in that memorable phrase — to get a horse. Today’s critics are more sophisticated. They assail our automotive culture for the pollution it has brought, for destroying the beauty of the countryside, for congesting the cities, and for a variety of other real and imagined sins too numerous to mention here.

Some of the critics’ charges are true, some are exaggerated, and some are completely false. But the important point is that the automobile is here to stay. Its use will continue to grow, not only in the United States, but in Europe and Asia as well. In the underdeveloped nations of the world, cars and trucks will exert enormous influence in raising the standard of living and providing millions with a cheap, fast, and comfortable means of transportation.

—“A Message from Henry Ford II,”

The Saturday Evening Post, November 1, 1976

An Automobile Genius on the Secrets of Innovation

This article and other features about the early automobile can be found in the Post’s Special Collector’s Edition: Automobiles in America!

This year the company for which I work — General Motors — is celebrating its 50th anniversary. For 40 of those years I have been a consulting inventor for the company. We sometimes hear it said that necessity is the mother of invention. If that were true, then it might be said that for the last several decades I have been working my head off because of necessity.

I can’t go along with this maxim altogether. Necessity was certainly not the mother of the airplane. At the time the Wright Brothers were inventing the airplane there was no widespread clamor to fly. People did not believe it was necessary. The Wright Brothers just thought they knew how they could do it and so they went ahead and thereby opened up a huge new field.

It might be argued that it has not been necessary to invent the automobile or to improve it through many inventions in the last 50 years. We would have lived with no more than the horse and the buggy. But I believe we are all thankful for 50 years of improvement in the automobile, and I am sure we will keep trying for more improvement just as hard in the next 50 years.

I am a little afraid of reminiscing. But to measure the possibilities of the next 50 years, it may be worth looking back over the last 50. It is amazing what the invention and development of the automobile and its applications have done to influence the habits and customs of our people in this period. Since 1908, manufacturers in this country have produced 160 million motor vehicles, and today the automobile creates 10 million jobs in highway-transport industries, more than one of every seven existing jobs. It has created a quarter of a million businesses like motels and service stations, and influenced the building of 2 million miles of roads. It has made deep changes in how people travel, how farmers grow and market crops, and where schools are built.

The automobile industry pays about $8 billion a year in taxes. Almost one quarter of the retail price of each vehicle is tax money. This is an enormous burden, yet the automobile industry has produced the greatest transportation system the world has ever seen. One of the most important reasons for this growth has been the industry’s willingness to change its product and its production methods to suit customers’ demands. The industry has been willing every year to design and build new tools which can produce more and better cars.

I do not advocate change for the sake of change, nor do I say that a new thing is necessarily better because it is new or suddenly popular. But if there is one thing the automobile has taught Americans in the last 50 years it is to expect constant improvement in the product. In America we must constantly change and improve or fade away.

Too often people believe that change comes about through the simple process of handing a problem to a research laboratory where an answer is produced mysteriously but promptly. There is no such magic in research. Discovery and invention come only by hard work, disappointments, innumerable failures, and very often the consumption of much time and money. Research is based on patience, skill, and practice and more practice. A theoretical physicist may develop an accurate formula for the curve of a baseball in flight, but it takes a pitcher years of practice to control the curve.

Since its inception the automobile industry has worked and practiced to lift the automobile from the status of a rich man’s toy. It was only a few years before General Motors was born that Ransom Olds discovered one of the secrets of mass production — progressive assembly. And it was just 55 years ago that Henry Leland, who was then head of Cadillac, demonstrated that automobile parts could be made interchangeable. These two developments were basically important to the automobile, but they alone did not make the product a perfect one. Leland understood this very well.

At that time the automobile was cranked by hand, which was not a job for women and usually meant they were relegated to the backseat as passengers. Hand-cranking was not popular with men, either, since there was a constant risk of broken arms. Leland disliked this imperfection and when a dear friend of his died as the result of an accident during hand-cranking, he sent me an invitation to visit Detroit and discuss the problem of making car-starting a safer operation.

This was one time when I might agree that necessity mothered an invention, because in a moment of weakness I told him that I thought a car might be cranked with an electric motor driven from a storage battery. Having made the rash statement it was up to me to produce it, and I worked for months in my small laboratory which was part of a barn in Dayton, Ohio. Eventually we did produce an electric starter, a modification of which became production equipment on the 1912 Cadillac.

This outraged the electrical-equipment engineers. They looked at their formulas and said that it was impossible, that we would need batteries and an electric motor larger than the engine itself and wires five times as heavy as we used. But they were thinking about continuous-running electric equipment. But we were not planning to transmit current 100 miles or work our electric motors 24 hours a day. We wanted a spasm of power, a big torque for a short time, and after the engine was turned over and started, the little starting system could lie back and rest and be recharged for the next start. So we disregarded the power rules and made driving possible for millions of people who couldn’t or did not want to hand-crank an engine.

Ten years later we could manufacture automobiles at the rate of one a minute, but they were not getting to the customer at that rate. It took one or two weeks to paint the car because the system that had been used on carriages was being applied to automobiles. The increased production resulting from the growing demand for closed cars could not possibly be met by using the old finishing methods.

Eventually the answer was found in the chemist’s test tube, although the you-can’t- do-it boys were on our necks all the time telling us we were wrong. Now, instead of several weeks to paint a car, it takes an hour to spray on the required number of coats of quick-drying, durable, colorful lacquer. The bottleneck to customers’ demands was broken.

In this business of ours you never solve one problem without, nine times out of 10, coming face to face with another one. After we had put electric starting, lighting, and ignition on the Cadillac we became sitting ducks for attacks aimed at us by the people whose toes we had stepped on when we electrified the automobile. In those days the quality of gasoline was hit-or-miss and the quality went down as automobile production went up. Engines began to knock all over the place. Naturally our competitors blamed the increasingly prevalent knock on our new ignition system.

In order to defend ourselves it was up to us to find out what really did cause knock. It was a problem that had also arisen with the Delco farm-lighting systems which I had originally devised so that my parents could have light and running water on their Ohio farm. To do this job we put a fellow inventor, Tom Midgley, to work studying this annoying matter of knock which was keeping us from increasing the compression in our engines. Happily neither Tom nor I was an orthodox chemist or thermal engineer, so we were wholesomely ignorant of the obstacles. We had a fine chance to make some informative errors in this field.

In the period before World War I, we had found out first just when knock occurred in the combustion chamber. It was after the ignition spark; and not before, as everyone had supposed. With this knowledge in hand we started a series of experimental treatments of the fuel. I remember that the first one was the introduction of coloring matter based on the heat-retaining characteristics of a certain flowering plant. We got a promising result, only to learn by checking with another substance that color had absolutely nothing to do with it. Nevertheless we learned something from that, and as we went on to test other additives a pattern of behavior began to appear.

The motoring public will never know how lucky it was that we did not stop in the middle of our experiments. The pattern indicated that the compounds of the heavier elements were most effective in squelching knock. We found two or three that were so good we might have been satisfied with their performance if it had not been for one thing — they smelled terrible. They smelled so bad and the odor was so lasting that the men in the laboratory who handled them were on the verge of becoming involuntary hermits. They didn’t dare go to the movies. But with the pattern leading us in the direction of the heavy elements, I suggested that we take a big leap and try the very heavy metal — lead.

The result of that leap was a whole bookful of trouble — and tetraethyl lead antiknock gasoline, which Midgley and his boys worked out and which is now known as Ethyl to everyone. Before we perfected Ethyl for widespread use, we had to develop a method of extracting huge quantities of the element bromine from the ocean. The chemists again told us this was impractical, since there is only one-tenth of a pound of bromine in a ton of sea water. But we found a way, and now we extract 120 million pounds of bromine from the sea annually. If you want to put a value on the result of our long hard search, in which the entire oil industry cooperated, you can do so in three ways. The superior fuel made possible more efficient high-compression engines. It permitted us annually to leave 25 billion gallons of fuel in our underground reserves which otherwise would have been burned. And at retail prices of gasoline the American motorist has been saving $5 to $8 billion a year.

You can see from just these few examples that the automobile industry was teethed on trouble. Complacency has no place in this business. You have to break out of the ruts if you want to survive. The fact that of about 2,500 makes of automobiles that have appeared only a handful are in existence today is a good illustration of what can happen if you design to suit yourself and ignore the wishes of your boss — the customer.

I am a great believer in the “double profit” system. The producer must make a profit to keep in business, but the customers’ profit must be ever so much greater. If you don’t believe some of these modern necessities, comforts, and conveniences have a definite value to you, just try doing without them. Suppose you were suddenly deprived of your car, electric lights, and power, or the telephone, radio, or television. What would you give to have them back?

—“Future Unlimited,”

The Saturday Evening Post, May 17, 1958

The Early Automobile Industry: It Doesn’t Pay to Pioneer

This article from the May 16, 1931, issue of the Saturday Evening Post was featured in the Post’s Special Collector’s Edition: Automobiles in America!

It doesn’t pay to pioneer; not in money, at any rate. Like my fellow pioneers, Haynes and the Appersons, C.B. King and Alex Winton, my name no longer is borne by any car. Only the name of our contemporary R.E. Olds is perpetuated in the Oldsmobile, though he long ago surrendered his interest in the names. Like most of them, I was a bicycle mechanic, and like all of them, a mechanic without technical training.

Why was the development of the automobile left to obscure mechanics without training rather than experienced engineers? Because of the weight of a unanimous and intolerant public opinion that the idea of a horseless carriage was too silly for words. In 1895, when I invited Samuel Bowles II, famous editor of the Springfield Republican, to ride in the Duryea which won the first American automobile race, his reply was: “I appreciate your kindness, but really, it would not be compatible with my position.”

The automobile was an absurdity, therefore it was ridiculous to be seen in one.

It is a mistake to suppose that the automobile was created to supply a demand. The demand was very painfully built up after the machines had been proved, and many of the pioneers foundered. Had I known historically what I was attempting I might have stopped with bicycles. I had the valor of ignorance. If Bishop Wright had sent his sons to engineering school, I wonder if they would have gone on to invent the airplane?

There are three reasons why America was destined to be the home of the automobile — great distances, scarce labor, and cheap fuel. It is surprising only that the automobile was so long delayed. The obvious ideal of mechanical locomotion was the greatest possible freedom of movement, but when Stephenson invented his steam locomotive, it was crudely heavy, while the public roads were bad. So railroads were built especially for the locomotive. In that way the cart got before the horse. Instead of simplifying and lightening the locomotive it was made heavier and heavier and more and more restricted to rails and a private right of way. That in turn fixed in the public mind the fallacy that no mechanically propelled vehicle belonged on the highway.

Hundreds of forgotten men however, did operate steam road vehicles of one kind or another in the century before the automobile age dawned. Nothing came of it because of public hostility. When the automobile era finally opened, the gas car was the Cinderella of the trade. The electric marvels of the trolley car, the telephone, and the Edison lamp had captured the public’s imagination. Until 1900 — and even later — one of the greatest obstacles the gasoline car had to overcome was the general conviction that any day Edison would invent a miraculous electric-powered auto that would sweep the market. Next to the electric came the steam car, because of public familiarity with steam and its 50 years’ advantage in engineering practice. Steam ran the railroads, electricity the trolley cars, while the internal-combustion engine was unknown to the layman.

The Chicago World’s Fair, in my opinion, deserves first credit for the automobile. Just as the Philadelphia Centennial sponsored the bicycle, Chicago stood godmother to the motorcar. In 1890 and 1891, the fair’s promoters advertised throughout the world in many languages for exhibits, offering awards for “steam, electric, and other road vehicles propelled by other than animal power.” Note the absence of any specific mention of the internal-combustion engine.

The First Auto Races gave cars needed dignity and prestige. A thousand experimenters who had been discouraged by ridicule took a fresh hitch at their trousers. I was one of these. What we were able to produce by 1893 was pitifully meager, but 1894 brought enough cars to permit a race in France, won by a steamer, and the next year the first American race was run at Chicago. My third car, begun late in 1893, won that race and a $2,000 prize over Europe’s three entries. It was, in my judgment, the first true automobile combining all modern essentials for the first time. Four Duryeas won all prizes, totaling $3,000, in the second American race on Memorial Day 1896. The same year two Duryeas won the first British road race, London to Brighton, against the best foreign cars.

It doesn’t pay to pioneer, and yet the first American inventor to put money into an automobile venture got his capital back with a profit. He was Edwin F. Markham, a nurse, of Springfield, Massachusetts. I was canvassing for funds to build our first model. Banks were out of the question, of course. The tobacconists of Springfield seemed to be prosperous, and I was concentrating on them this day in the early 1890s. Markham, lounging in one shop, overheard my sales talk. In return for a 10th interest, he agreed to pay bills up to $1,000. If he financed us to a self-supporting basis he was to get a half interest. Eventually he put up $3,000 and got back about $5,000. He lived to see the automobile a commonplace and was very proud of his vision.

—“It Doesn’t Pay to Pioneer,”

The Saturday Evening Post, May 16, 1931

Get A Horse! America’s Skepticism Toward the First Automobiles

This article from the February 8, 1930, issue of the Saturday Evening Post was featured in the Post’s Special Collector’s Edition: Automobiles in America!

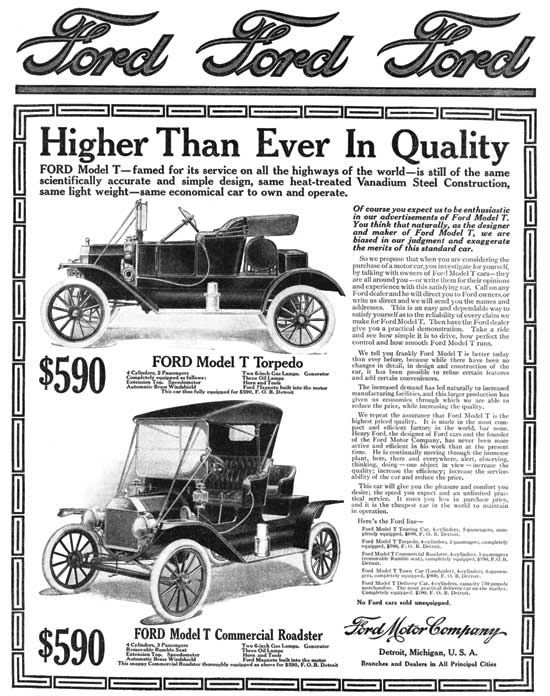

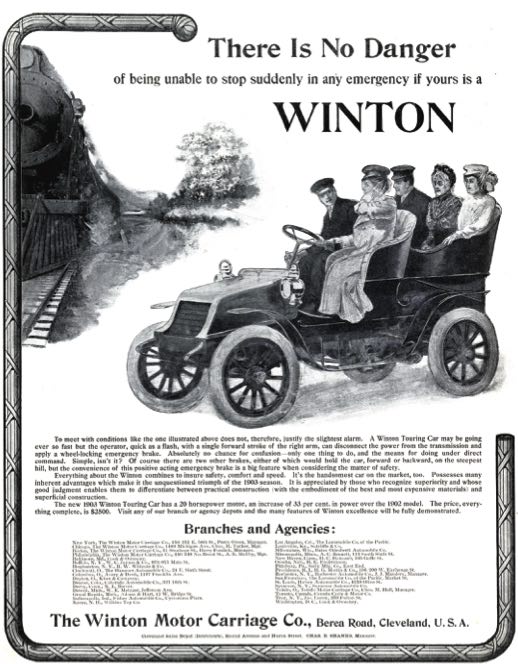

In 1930, Alexander Winton, by then one of the legends of the auto industry, wrote this article for the Post about the wild early days when even promoting the idea of a self-propelling machine would make you the object of ridicule. Winton was a bicycle maker, and as he writes below, he soon became infatuated with the idea of a bicycle that “a rider wouldn’t have to push and keep pushing.” In 1896, he founded the Winton Motor Carriage company, and soon began turning out cars at the dizzying rate of four per year. He would sell his first car in 1897 — arguably the first automobile sold in the U.S. — for the princely sum of $1,000.

There has been much argument as to who made the first automobile in this country. My own conviction is that the honor belongs to Charles E. Duryea. I began serious experiments in 1893, and I am sure Duryea was conducting them prior to that year. But whether Duryea built the first automobile or whether he didn’t, the fact remains I built, and sold, the first American- made gasoline car.

The exact date of the sale was March 24, 1898, and about a week later — on April 1, 1898 — I received payment and shipped the car to its new owner, Robert Allison, a mechanical engineer of Port Carbon, Pennsylvania. I bought it back after Allison had used it a few years, and it is now in the Smithsonian Institution, in Washington.

When I first contemplated the application of gasoline for vehicles, I had a bicycle plant in Cleveland. Because bikes interested me, my mind naturally turned to something a rider wouldn’t have to push and keep pushing if he was trying to get some place. But the great obstacle to the development of the automobile was the lack of public inter- est. To advocate replacing the horse, which had served man through centuries, marked one as an imbecile. Things are very different today. But in the ’90s, even though I had a successful bicycle business, and was building my first car in the privacy of the cellar in my home, I began to be pointed out as “the fool who is fiddling with a buggy that will run without being hitched to a horse.” My banker called on me to say: “Winton, I am disappointed in you.”

That riled me, but I held my temper as I asked, “What’s the matter with you?” He bellowed: “There’s nothing the matter with me. It’s you! You’re crazy if you think this fool contraption you’ve been wasting your time on will ever displace the horse.”

From my pocket I took a clipping from the New York World of November 17, 1895, and asked him to read it. He brushed it aside. I insisted. It was an interview with Thomas A. Edison: “Talking of horseless carriage suggests to my mind that the horse is doomed. The bicycle, which, 10 years ago, was a curiosity, is now a necessity. It is found everywhere. Ten years from now you will be able to buy a horseless vehicle for what you would pay today for a wagon and a pair of horses. The money spent in the keep of the horses will be saved and the danger to life will be much reduced.”

“It is only a question of a short time when the carriages and trucks of every large city will be run by motors. The expense of keeping and feeding horses in a great city like New York is very heavy, and all this will be done away with. You must remember that every invention of this kind which is made adds to the general wealth by introducing a new system of greater economy of force. A great invention which facilitates commerce, enriches a country just as much as the discovery of vast hoards of gold.”

The banker threw back the clipping and snorted, “Another inventor talking.”

Wild Ideas

In the uncertainty of what the public would want, a great many strange contraptions were put together. Joseph Barsaleaux, a blacksmith of Sandy Hill, New York, built a motor horse. In his device, the horse moved on a single wheel about two feet in diameter, with the wheel attached to the shafts just as was a live horse. Reins attached to the mouth of the horse served as a steering gear, because the machinery was inside the horse and had to be regulated some way. The contraption weighed about 550 pounds, had a cruising speed of six miles an hour, and attracted some serious attention.

In Washington there was a vehicle which gained its power by using compressed city gas. George Elrick of Joliet, Illinois, was busy with an engine having no wheels or gears and which manufactured its own gas as it went along. D.I. Lybe of Sidney, Iowa, was the owner of patents on a spring-motor device which stored energy running downhill and used it going uphill, while on level ground he claimed his vehicle would cover 2,000 feet at a maximum speed of 30 miles an hour. Compressed air and superheated water were to be employed by another company. At the time there was more money and in uence back of that idea than was behind all the gasoline-car manufacturers put together.

Cars with steam propulsion came in — not one or two but more than 100. Electric vehicles clogged the market, but in the end, public opinion turned to gasoline because it was clean, safe, and dependable.

In spite of my banker’s displeasure, I went ahead with my model and finally had it in such shape that I thought it would run. All I needed to finish the job was a set of tires. I went to the Goodrich Company, in Akron, and told them I wanted something bigger than their biggest bicycle tire, something that would fit the wheels of a horseless carriage.

“That’s a new one on us,” cried a man to whom I had been directed.

“A horseless carriage, eh? Hmph! Will it run?”

“You bet it will.”

“Well, I guess we can make them, although we never have.”

“That’s fine.”

The man hesitated, rubbed his chin, and observed: “We will make them, but you will have to pay for the molds.”

“Do what?”

“Yes, sir. There won’t be enough call for tires for horseless carriages, and we can’t afford to pay for the molds. Also, you will have to pay for them in advance — and the tires too. We’ll have them on our hands if you don’t get them.”

I paid.

They were single-tube affairs, and were pretty expensive. It wasn’t long before I got a puncture, and while I thought of patching the tire I figured out what I considered a better idea. Molasses was heavy and would stop leaks if they weren’t too large, so I began pumping it into the tube. I pumped too hard. The rubber gave way and the molasses came out too quickly to be dodged.

The First Road Trip

That first car worked pretty well, but I saw so many things wrong with it that I started another, using part of my bicycle factory for the work. I foresaw a future in automobiles and tried to interest some people in starting a manufacturing plant. Failing in that, I decided to go on a long trip, hoping attention would be attracted to the machine.

In July 1897, I confided in a friend: “I am going to drive my horseless carriage from Cleveland to New York. I am inviting you to come with me.”

He laughed at me. I sought another friend.

On the morning of July 28, 1897, Bert Hatcher and I left Cleveland. The Horseless Age, one of the few motor publications of that time, wrote about us this way: “Combining business with recreation, Alexander Winton left Cleveland with a companion in a new motor carriage on the morning of July 28, and after a leisurely journey he reached New York City Saturday, August 7. From Mr. Winton’s account, no greater test could have been given the machine as, to use his own words, ‘the roads were simply outrageous.’ Fully two weeks of rainy weather had preceded him on the journey, and in many places the mud and water were hub deep, and in some places the sand was equally as bad. He traveled fully 800 miles, and the best day’s run was 150 miles. The machine consumed on an average of six gallons of gasoline a day, which would be little more than half a cent a mile for the trip. Much interest was shown by the people on the road and especially by those in the mountains.”

Hatcher and I did not return by motor. We had blisters enough. You may wonder why, on this first trip ever attempted by an automobile over a long distance, we were able to complete a day’s journey on an average of six gallons of gasoline. The fuel was more volatile in those days, and we had a low-speed motor. The present high-speed motor uses a great deal more fuel, but it is a more adaptable engine for the needs of modern travel.

In those days there were no gasoline stations, and the only place the fuel could be purchased was in a drug store. If, by chance, the druggist had a gallon of it, we were happy. Seldom were we able to buy in such a large quantity and usually we had to be content with a pint or a quart.

But aside from generous newspaper space, the trip attracted no attention. I waited for months, but no financiers came to put their tall silk hats on my desk.

Finally, however, the afternoon came when an assistant told me: “Mr. Metcalf is waiting to see you.”

“Who is he?”

“I don’t know.”

I hesitated, then said; “Send him in.”

The man came in and introduced himself. “My name is Irving D. Metcalf. I am from Oberlin College.”

“A professor?”

“Yes, sir.”

“You want to see my horseless carriage?”

“Yes, I do.”

“There it is” — and I jerked my thumb over my shoulder to indicate the machine standing in a corner of the room.

I turned to resume some sketching I was doing when I heard Mr. Metcalf say: “Would you mind explaining it to me? I’ve read so much about that machine that I’m convinced you have a good thing and, if you have no objections, I’d like to invest a little money with you.”

I wasted no time in accompanying him to the machine and explaining its workings.

“How many can you build and sell the first year?” he finally asked.

“Four.”

“Sell me some stock?“

“If you want it!”

“How much can you spare?”

I almost held my breath. “Five thousand dollars’ worth.”

“All right.”

Up to that time no company had been organized to build and sell a gasoline automobile.

Not in this country, at least. So Metcalf became the first outside holder of stock in such a company.

We did not know where our customers would come from, but we were sure they would come. We started building four machines, and when one was finished, Robert Allison, hearing that I was manufacturing automobiles, came to Cleveland.

He wanted a ride. I told him to hop in, and then proceeded to give the first of many millions of demonstrations that since have preceded the sale of automobiles. We started out about noon and did not return until after supper. During the afternoon he had me drive to a dozen places where friends of his were working, and from each he sought advice. After each stop he had a new set of questions, but apparently I answered them satisfactorily, for when we returned to the factory he asked: “How much do you want for this carriage?”

“One thousand dollars.”

“I’ll buy it.”

Within a short time we sold the other three machines, getting $1,000 apiece. Our profit on each was $400. By the end of 1898 we had built and sold 25 carriages, and this was such an amazing production that no one believed it. I had to publish a statement telling the names of the owners and when their machines had been delivered.

We were beginning to show a return on the original in- vestment, to build a business, and to start a gigantic industry. Those were vastly different days in manufacturing to what we now have. We had no long lines of broaching machines, multiple drills, cylinder grinders; no endless chains moving along parts to points needed. There was little of the time-saving of modern manufacturing methods. We had to develop to meet those demands, and in starting off, our tools consisted of the standard drills and lathes, plus good mechanics. Every workman we had in those days was a good mechanic. He could not hold a job unless he was. He didn’t spend his days or his years putting on a nut here or a screw there. If we needed spark plugs, he had to jump in and make them. He had to know how to ream out a cylinder. All argument to the contrary, I believe American life has lost something in the passing of the good mechanic and the widespread adoption of the automatic machine. For one thing, men have lost much of their usefulness to themselves. But that is beside the point.

No Secrets

We used foundry castings for cylinder blocks and, usually, the castings came to us with holes in them. Such a thing as rejecting the castings never occurred to us; we were too glad to get them, because foundry men weren’t entirely sold on the idea of making them. We plugged the holes with cast iron and said nothing. We made our own spark plugs — first out of mica, and then out of porcelain. Steering wheels were individualized ideas, not standardized equipment. One day Henry Ford came to Cleveland with a racing car. He had a steering wheel he had made himself and which spun around a number of times before he could get the car going in the desired direction. “Ford” I told him, “you are going to kill yourself with that thing.”

“Why?” he asked.

“Because you can’t control your car with it.”

He allowed as though I might be right.

“You know I’m right,” I told him, and added I would send him blueprints of the wheel and gear I was using.

He thanked me, but instead of sending him the blue prints, I boxed up a complete outfit and shipped it to Detroit. He found plenty of use for it. The steering wheel was one of my early patents, and it was the same wheel that came into later and general use. It is but one of more than a hundred patents I hold on different parts for automobiles.

I believe I am entitled to say I have never collected a cent in royalties from them, nor will I. Lawyers have tried to argue me into bringing suits for infringements, but it so happened we pioneers always worked together. We loaned ideas. We loaned tools. We loaned patents. If we worked out a good idea, we loaned that. You see, some 20 years ago there was a man named George Baldwin Selden, a lawyer and inventor living in Rochester, New York, who caused a lot of trouble and expense to the automobile industry by bringing suit against all of us for the infringement of a patent that had been granted him on May 8, 1879. His patent covered a machine containing the essential principles of an automobile.

He tried to interest various persons in his idea, failed for years, and then entered into an agreement with William C. Whitney, an Eastern capitalist, on November 4, 1899, under which he turned over exclusive rights to his idea. Whitney purchased control of the Electric Vehicle Company and then began a vigorous enforcement of his claims. The Winton company was the first to be attacked because it was the largest, and though we put up a vigorous defense, we lost the first court fight. We appealed the case and, while waiting to be again heard, entered into an agreement with other manufacturers to pay certain royalties to Selden and Whitney.

For years Selden was in the courts, until, in January 1911, in the United States Circuit Court of Appeals, the validity of the Selden patent was upheld, but the defendant — the Ford Motor Company — was held to be not liable, because it was manufacturing a motor of a type known as the Otto engine, whereas Selden’s claims described one known as the Brayton type.

All of us were following the Otto principles, so that decision relieved us of further contributions to Selden and his backers. But the unpleasantness of all those suits brought together the manufacturers for an exchange of ideas and mutual protection. I am still old-fashioned and believe it was a good thing.

Self-Reliance

We made our own radiators. These cooling devices were nothing more than banks of tubes through which water could ow. During summer months, on Saturdays and after-school hours, we used to have boys come in and string square tin washers, with a jagged hole punched in the center of each, on the tubes. When the washers were all in place we would dip the tubes in solder so as to make them one part.

We made our own carburetors. The first device used was a tube which went down nearly to the bottom of the gasoline tank. Air went through it, was forced into the gasoline, and when the impregnated mixture reached the top, it was suctioned off and passed through a valve between the tank and the engine, so the mixture would be made lean enough to be combustible. That contrivance didn’t work any too well, so we made a mixer which was an ordinary valve and pipe through which the gasoline could pass on its way to the motor. Out of the mixer came the present carburetor. In the one we built I had a hole punched in the bottom so the air could reach the gasoline. One day I received a frantic letter from a Brooklyn doctor who had purchased one of my cars.

A few days later I was standing in his barn, looking at the machine, which, he said, wouldn’t run.

I examined the gas tank. It was all right. I looked over the spark plugs. Tested the batteries. Got down under the car and stared up underneath. Everything seemed all right, so I went around in front and spun the motor. It was dead. Finally I ran my fingers under the mixer.

Then I broke in on the physician’s sarcastic twitterings with this question: “Why did you plug the hole in the bottom of the mixer?

“To keep the gasoline from leaking.”

“Have you ever studied chemistry?”

“Certainly.”

“I see. But you never learned that an explosion is impossible without a mixture of some sort. In this case it happens that gasoline has to be mixed with air before results can be obtained.”

It was my turn to be sarcastic. I punched another hole in the mixer, drained off the gasoline which had flooded the cylinders, put the fluid back in the tank, turned the crank, and started the motor.

That was one thing we pioneers in automobiles had to do that presidents of companies miss today. We had to give personal service to our customers. Many times I have piled out of bed on a winter’s night to aid a stranded driver. A good many times, too, I left my telephone receiver off the hook so I could get some sleep.

Batteries, so dependable now, were practically useless as they then made them. The battery was nothing but a receptacle holding containers, or cups, filled with the active acid fluid. These cups were made of carbon, and after a car had traveled a couple of blocks the cups were almost sure to break, spilling their contents and rendering them useless.

A man named Nungesser was building ours, and they were causing me so much trouble that I refused to put them in the cars. I went to Nungesser and said to him: “I want you to tell me the truth. For weeks you have been promising a dependable battery and you haven’t delivered. What’s wrong? Can’t you make one?”

His face flushed as he admitted: “I can’t, Mr. Winton. I’ve tried everything and can find nothing.”

That was bad news for me. I went into his plant, looked over various experiments and finally suggested: “Why don’t you use a wire gauze for your cup instead of carbon?”

“A wire gauze?”

“Yes. Use copper. It is flexible and will not deteriorate in the acid solution.”

He tried it and it worked. Worked so well that he o ered me a half interest in his business. I declined, although it would not have cost me a cent. I told him I was having troubles enough in the automobile business. That suggestion solved battery difficulties for a good many years and was really the beginning of the present storage battery. Nungesser later sold out to one of the big battery companies for an appreciable sum of money.

The Demise of the Half-Cranked Starter

We made our own fans, our own differentials, transmissions, frames, brakes. I built the first two-braking system, and a Winton car was first to be equipped with internal and external brakes on the one drum.

This was another of my patents, and it is only in the last few years that four-wheel brakes have taken the place of those I worked out. We built our own starters. We had an air starter that took the pressure from the cylinders, stored it in a tank, and kept it ready for use. This air starter was the forerunner, in a sense, of the present electric starter.

It came about in a simple way. I was looking at a car one day when one of my men came along and began cranking it. The motor was cold and it was hard work.

“Next year we are going to equip our cars with starters,” I told an associate, standing with me.

“You mean so cars won’t have to be cranked?”

“Yes.”

“How can you do that?” There was doubt in his voice.

“That’s what I’m thinking about.”

I went inside, made a drawing of the idea that had come, built a mechanism that could be operated by pressing down a foot, and we had the starter.

Dishonest Practices

If there was orderliness in our shops, there was vast confusion in the fledgling industry. Not only did we have to fight all the time to get things done but after we had them finished we had to pitch in and fight the wildcat automobile companies on the outside. It was difficult for the public to distinguish between the genuine and the ephemeral, and there are towns that can still point to windowless factories that were built from the stock sold by glib promoters, but which never manufactured more than two or three cars. Orphan cars were numerous and always were a 100 percent liability, because it was impossible to get replacements for broken parts. The big accessory companies that now help the industry did not exist.

Dishonest practices did much harm during years when support was most needed.

The orphan-car situation became so serious that the White Company — another of the pioneers — gave publication to this advertisement: “In a reserved and guarded way we have several times spoken of the desirability of purchasing a car made by a substantial firm possessing ample capital. In the last few months many concerns which have embarked in the manufacture of automobiles have discontinued, while others have withdrawn from actual business and their organizations have been scattered.

“The man who has bought a car from such a concern learns too late that he has a car on his hands which is the next best thing to useless and worthless simply because duplicate parts cannot be obtained. It is of utmost importance that the purchaser should inquire very thoroughly into the stability of the concern from which he buys, and that the order of a car at a special price is apt to be an incident of a closing-out sale.”

When you know that more than 500 automobile companies came in and went out in those first few years, you will better understand some of the forces working against those of us who were honestly trying to succeed. We pioneers had to be conservative.

‘Visionary to the Point of Lunacy’

I remember that back in 1899 a bus line was announced to operate between Chicago and St. Louis. All of us believed bus lines would come some day, but we knew the public was not ready to accept such a dream. And, indeed, E.P. Ingersoll, a reporter on automobile topics, wrote the following widely circulated opinion piece: “The notion that electric vehicles, or vehicles of any other kind, will be able to compete with railroad trains for long-distance traffic is visionary to the point of lunacy. The fool who hatched out this latest motor canard was conscience-stricken enough to add that the whole matter was still in an exceedingly hazy state. But,if it ever emerges from the nebulous state,it will be in a world where natural laws are all turned topsy-turvy, and time and space are no more. Were it not for the surprising persistence of this delusion, the yarn would not be worthy of notice.”

We were trying to keep public interest, suddenly aroused, within reasonable boundaries. Aside from making cautious predictions, we had other diversions. Stirring word battles were fought in the greatest wilderness of all — the wilderness of terminology. Some wanted “horseless carriage” as a standard description; others recommended “polycycle,” “syke,” “motor wagon,” “motorcycle,” “horseless-carriage bicycle,” “road locomotive” — I guess there were a hundred names, but “automobile,” because of its easy rhythm, won out.

The Ford-Winton Race

Another thing we had to do which no president or executive of an automobile company of today would think of doing was to compete against each other on race tracks. Duryea, Walter C. White, Ford — we all used to race. That is how we attracted attention to our products. The public looked upon racing as a test of an automobile’s worth, and to a great extent it guided its buying habits by the results of the contests.

Ford got his first big reputation when he raced me at the Grosse Pointe track in Detroit. The day was October 10, 1901. Prior to that time Ford was little known. The first mention of him in connection with the motor industry, so far as I have been able to find, was in a small item in an issue of The Horseless Age, printed in 1898. It read: “Henry Ford, of Detroit, Michigan, chief engineer of the Edison Electric Company of that city, has built a number of gasoline vehicles which are said to have been successfully operated. He is reported to be financially supported by several prominent men of the city who intend to manufacture the Ford vehicle. From Mr. Ford himself no information can be gleaned regarding his vehicle or his plans for manufacture.”

For some time prior to 1901, I had been the dirt-track champion driver, and when I received a challenge to race Ford in Detroit I accepted. A number of cars started, but the event soon narrowed into a test between my car and Ford’s. The Detroit News, on the day following the race, described the event: “Winton took the lead at the start and held it easily for five miles. Then the Detroit car began to creep up, and right in front of the grandstand, on the seventh lap, Ford forged ahead. Winton seemed to lose his power. His great car began to smoke and he was out of the race.”

Ford won, of course, and in winning, attracted national attention. Afterward he said, “Put Winton in my car and he’ll beat anything in this country.”

I told him I’d put myself back in my own car and beat him any time he came on the track.

The following day he announced: “I will never again be seen in a race.” Nor was he.

Those were great days. Lots of hardships. Lots of quarreling. Lots of satisfaction too. No paved highways for automobiles to shoot along at 60 and 70 miles an hour; just country roads, filled with ruts, sand, and mud, over which no one wanted to drive at the maximum speed of passenger cars, which was about 30 miles an hour. But every trip was a different adventure.

—“Get a Horse,”

The Saturday Evening Post, February 8, 1930