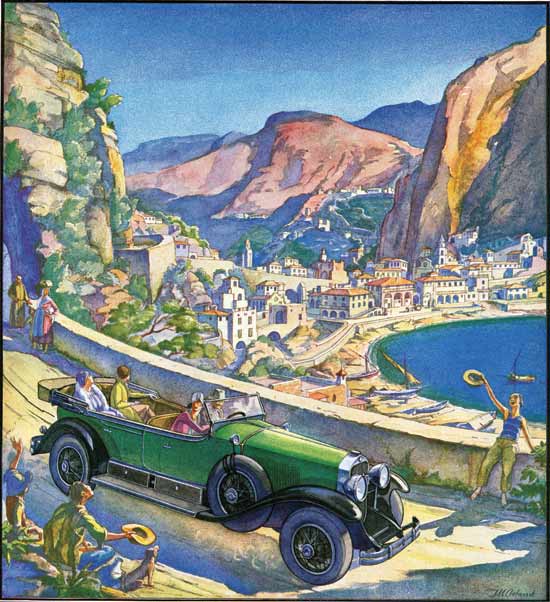

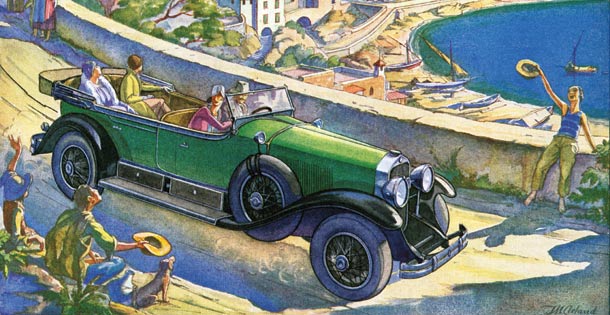

This article and other features about the early automobile can be found in the Post’s Special Collector’s Edition: Automobiles in America!

In this 1922 essay, the author points out that the vast changes underway to accommodate the automobile were about to vastly alter the character of towns across America, as was already happening in cities like New York and Chicago. But far from lamenting the coming changes, the writer describes them as essential to progress.

Tomorrow you may not know your own city. They have probably begun altering it already, or are planning to do so. Tomorrow your city will have wide boulevards cut through its narrow streets. These will accommodate four, six, and eight lines of traffic. They will start at the center and run miles out into the country. Thousands of buildings will be torn down. Sharp street corners will be rounded off and the circle and crescent take the place of the checkerboard.

Did your city fathers, years ago, lay out a downtown boulevard or two with a strip of parkway in the center? That beauty spot will be needed for traffic. Slums and tenements will disappear too. There will be a general grading up of living standards and an equalization of real-estate values.

When you drive a car the traffic cop will no longer be able to bawl you out, for he will disappear from street crossings, guiding traffic by electric signals from a point where he can see everything but say nothing — that is, if he doesn’t disappear altogether.

When you go for a walk it will be a far safer and more comfortable form of exercise than today, for the bulk of automobile traffic will either be transferred to elevated roads for automobiles alone, or disappear into tunnels. The trolley cars will disappear underground or be replaced by buses, which are not only more flexible than the trolley, dodging in and out of traffic, but are more flexible in routing.

Your city will be linked with others all over the state and country by great trunk motor highways, with lighted traffic signals, and perhaps traffic officers. Much of the motor travel between cities will be out of sight, on separate highways that do not enter the towns at all, but skirt them.

The automobile is at the bottom of all these changes. With the number of cars increasing to, in some cases, one for every two families, our cities have developed street traffic comparable with high blood pressure.

“Say, that thing’ll never be practical!” exclaimed a New Yorker when he first saw a horseless carriage. “Why, a man has to go ahead of it with a red flag!” Within five years he was driving an automobile himself. When horses and pedestrians became accustomed to the automobile, the man with the red flag was no longer necessary. But today he is again walking ahead, figuratively, as the traffic policeman. This is fundamentally wrong. “Speed limits on the automobile are a paradox,” says a New York trade-journal publisher. He writes: “The automobile is designed to run fast. That is its whole function, attraction, and service. Limit it, and you lose all its benefits. Speed limits and traffic control have become necessary because we have not yet learned to separate the automobile from slower traffic, and give it highways of its own.”

Few of our cities were really planned — for the most part they just happened — and even the best city plans of our fathers and grandfathers have been outgrown. The cowpath origin of city streets is familiar and amusing. People delight in its absurdities, getting lost in Boston’s old waterfront mazes, and verifying the fact that Pearl Street, in lower New York, crosses Broadway twice. A cowpath town was often most convenient for getting about, so long as everything was built within walking distance, allowing goods to be delivered by wheelbarrow. When it got larger, the cowpath section was extended on a checkerboard plan providing for growth, but usually with streets too narrow for present-day traffic, and with far too few parks and breathing places. If granddad was very farsighted he laid down a combination of checkerboard and turnpike, as in Washington and Indianapolis, the turnpikes radiating like the spokes of a wheel, providing lines of growth, and also highways by which farmers could bring in food from the surrounding country.

In general there are only these three kinds of towns, cowpath, checkerboard, and cartwheel. A cowpath town tends to congestion at the center rather than healthy growth at the radius, and makes dandy slums. The checkerboard town grows faster. The cartwheel town grows fastest of all, and most evenly and healthily.

Today we have better information than previous generations upon which to plan cities for the future. But we are dealing with city difficulties piecemeal. When traffic begins to tangle at a certain corner, we put a policeman at that corner to straighten traffic out. The tangle spreads up and down as traffic grows. We put more policemen on more corners, then lift them into towers and organize control in units of five or 10 blocks. But mere streets become impossible for handling all the traffic. Street cars, automobiles, motor trucks, horse vehicles, and pedestrians must be separated and given their own right-of-way where none can hamper or endanger the others.

—“Your Town Tomorrow,”

The Saturday Evening Post, April 1, 1922

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

This 1922 feature seems to have predicted the future accurately in a number of ways, including underground travel and wide boulevards. Other things he writes of here like the cowpath, checkerboard and cartwheel towns I don’t really understand. I’m sure these references were clear to people in the early ’20s.

I can say that traffic cops have made a few appearances (when they can) this week in disaster-prone California where the rain and wicked storms shorted-out quite a few traffic lights. Having a policeman/woman directing traffic makes 4- way stops and left hand turns a lot less stressful and safer under these circumstances, and am very grateful when I see them.