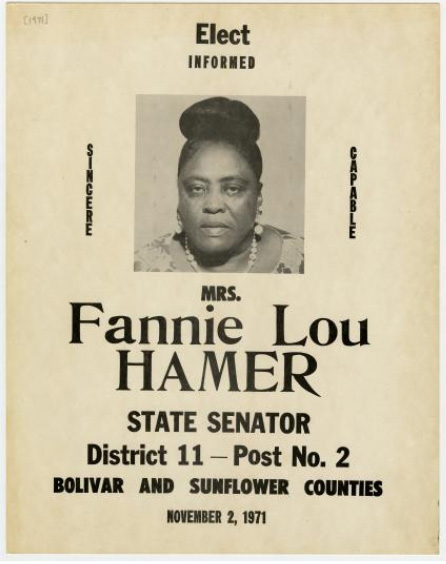

Fannie Lou Hamer’s War on Voter Suppression

Lyndon B. Johnson was distressed a few days before the start of the 1964 Democratic National Convention. In a presentation to the party’s Credentials Committee in an Atlantic City hotel ballroom, a Black Mississippi woman named Fannie Lou Hamer was giving a disturbing account of her various past attempts to exercise her right to vote. She was “sick and tired of being sick and tired.”

Hamer, then 46 years old, had been the youngest of 20 children in her family, leaving school in sixth grade to work on Mississippi plantations. She had been poor her entire life, and suffered from polio as a young girl. Just three years earlier, she had been sterilized against her will while hospitalized for a minor surgery. But her address to the 108 committee members that day recounted, in sickening detail, numerous instances of violent institutional repression that had prohibited Hamer from participating in her country’s — and the Democratic Party’s — democratic process.

She first failed the arcane and discriminatory literacy test that was administered to African Americans in 1962. Then, she was on a busload of hopeful Black voters that was pulled over for being the wrong color (too yellow). Then, the plantation owner kicked her off the land she sharecropped (for attempting to register to vote). Then, in 1963, she was arrested with several others after attending a voter registration workshop. While in jail, she was brutally beaten with a blackjack by other prisoners at the orders of a state trooper who told them to, according to this magazine, “Make the bitch wish she was dead.”

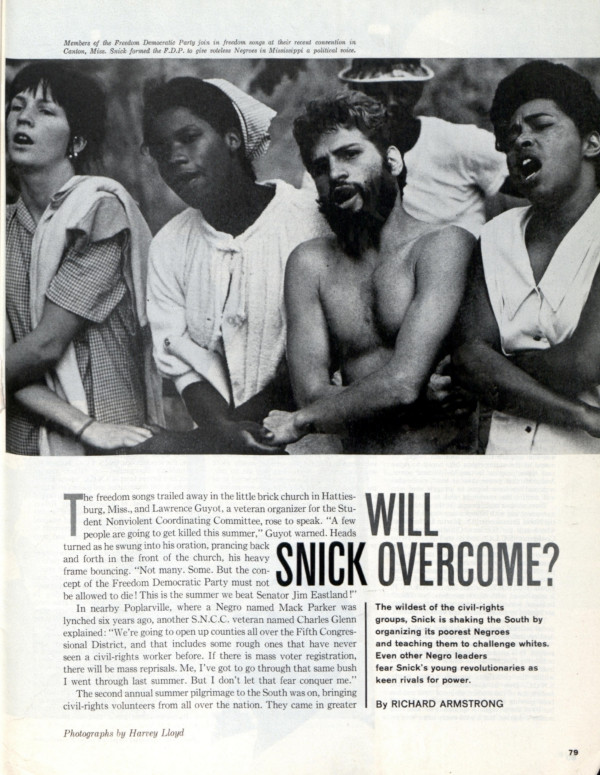

At the Democratic Convention, Hamer was speaking on behalf of the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party, a grassroots political project that aimed to replace the state’s elected delegation on the premise that it was illegally selected with a segregated vote — a “white primary.” Less than seven percent of eligible Black adults were registered to vote in Mississippi in 1964. With the cooperation of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC or “Snick”), NAACP, Southern Christian Leadership Conference, and the Congress of Racial Equality, activists in the South organized tens of thousands of mostly Black, poor and working-class people in a precinct-level effort to subvert the all-white Democratic stronghold in the state.

President Johnson worried that the MFDP — and a potential interracial delegation — would alienate the South’s white Democratic voters, sending them into the arms of the Republicans. During Hamer’s speech, he called an impromptu press conference, leading many to think he was about to announce his running mate. Instead, he gave a commemoration of President Kennedy, who had been assassinated nine months earlier. The television networks still played Hamer’s speech, though, during their primetime broadcasts. Their viewers saw the poor Black sharecropper’s impassioned indictment of her country: “Is this America, the land of the free and the home of the brave, where we have to sleep with our telephones off the hooks because our lives be threatened daily, because we want to live as decent human beings, in America?”

Hamer’s testimony was an uncomfortable dose of reality for liberal America. Even today, her story teaches largely unexamined lessons regarding the background work of the civil rights movement and its many proponents. As scholar Maegan Parker Brooks wrote in her recent biography of Hamer, “The life story of a disabled, impoverished, middle-aged black woman from the rural Mississippi Delta challenges widespread perceptions of who participated in — as well as how they influenced — mid-twentieth century movements for social, political, and economic change.” Hamer is not a household name like Martin Luther King, Jr. or John Lewis, but her role in this transformational period of American history shows us what was at stake, and indeed still is.

Hamer didn’t appear at the 1964 Democratic National Convention out of thin air. Along with three other Black candidates in the state, she ran a primary campaign against the longtime Mississippi representative Jamie Whitten. The Freedom Democrats had been working since the previous fall to both register Black Mississippians and hold straw votes in their own “freedom-registration books” to show what electoral participation could look like in the state where African Americans made up 42 percent of the population. That summer, a profile of Hamer in The Nation posited that “The wide range of Negro participation will show that the problem in Mississippi is not Negro apathy, but discrimination and fear of physical and economic reprisals for attempting to register.”

During the Freedom Summer of 1964, the civil rights groups that made up the Council of Federated Organizations undertook a statewide organizing effort to account for Black non-voters and register as many as possible. They also established Freedom Schools, community centers, and a Freedom Labor Union. At the heart of this undertaking was the oversized contribution of SNCC, the activist group Hamer had worked with diligently since attending a mass meeting in 1962. Hamer traveled around the state, stirring Black audiences with speeches that motivated them to act for their own liberation. (“It’s a shame before God that people will let hate not only destroy us, but it will destroy them. Because a house divided against itself cannot stand and today America is divided against itself because they don’t want us to have even the ballot here in Mississippi.”) At the same time, SNCC’s army of volunteers — largely white college students from the North — were moving around Mississippi organizing for participatory democracy at every level.

In 1965, this magazine covered the student group (“Will Snick Overcome?”), pointing out the markedly more radical approach SNCC employed compared to a group like the NAACP. Arising from the sit-ins of 1960, SNCC was an early opponent of the Vietnam War and decidedly non-hierarchical. While it claimed manpower from the country’s college students, SNCC aimed to cultivate leadership at the community level in its campaigns. The Post recognized this unique tactic of SNCC’s “shock troops,” even if it seemed tedious: “The whole concept of building a political force out of tenant farmers, slum-dwellers and the unemployed is a radical departure from American political norms.”

In response to claims that communists and Marxists — perhaps even foreign ones — were stirring up all of the trouble in the South, Hamer gave a simple response in a speech at a mass meeting in 1964: “People will go different places and say, ‘The Negroes, until the outside agitators came in, was satisfied.’ But I’ve been dissatisfied ever since I was six years old.” Hamer’s lifelong dissatisfaction steered her toward a fight for voter enfranchisement, and later, as Brooks puts it in her biography, fights “against white supremacy, police brutality, sexual assault, segregated education, food insecurity, and health care access” among others.

In June, before the convention, three Freedom Summer organizers — James Earl Chaney, Michael Schwerner, and Andrew Goodman — were murdered near Philadelphia, Mississippi. The Ku Klux Klan had grown its numbers in the area and burned down 20 black churches that summer, many of which were hubs for civil rights activity. The three men had been involved with a church that housed a Freedom School, and several Klansmen, policemen, and a minister conspired to shoot them and hide their bodies. The case was a national outrage, but over the course of the federal investigation eight bodies of Black men were found, several of them civil rights workers as well.

After Hamer made the MFDP’s case to the Credentials Committee at the convention, the Johnson administration countered with a negotiation offer: the MFDP could have two at-large seats (picked by Johnson) without unseating any of the Mississippi delegation, and the party would ban segregated delegations in 1968. Hamer and other Freedom delegates were fuming at the prospect of accepting such a paltry deal, but leaders from the NAACP and SCLC, including Martin Luther King, Jr., advised them to take it. The MFDP unanimously voted against accepting the offer, in an outright rejection of the legitimacy of the Mississippi delegation.

That repudiation is an important aspect of Hamer’s legacy in that it refuses to conform to what author Jeanne Theoharis calls the “national fable” of the civil rights movement: the idea that this era of our history can be represented as a settled legislative triumph featuring a small cast of iconic heroes instead of as a disruptive, radical mass movement against institutional white supremacy. Hamer was not interested in a reassuring narrative for white folks; she wanted liberation.

The next month, Harry Belafonte took a group from the MFDP — including John Lewis and Fannie Lou Hamer — on a trip to Guinea. They were received with a warm welcome, meeting President Ahmed Sékou Touré and touring his palace. On the trip, Hamer wrote in her autobiography, she felt she was treated much better in Africa than in America, and she noticed many of the negative stereotypes she had been led to believe about Africans were incorrect. “So when they say, ‘Go back to Africa,’” she wrote, “I say, ‘When you send the Polish back to Poland, the Italians back to Italy, the Irish back to Ireland and you get on that Mayflower from whence you came and give the Indians their land back.’ It’s our right to stay here and we stay and fight for what belongs to us.”

Featured Image Courtesy of the Archives and Records Services Division, Mississippi Department of Archives and History

50 Years Ago, Flip Wilson Changed the Face of TV Comedy

Flip Wilson started working his way up the comedy ranks in the 1950s, but his big break came in 1965. That’s when Red Foxx told Johnny Carson on The Tonight Show that Wilson was the funniest comedian out there. Carson put him on, and stardom followed. Within five short years, Wilson was at the helm of his own variety and sketch-comedy show, The Flip Wilson Show. The trailblazing series saw Wilson become one of the most visible and popular Black entertainers in America. On the 50th anniversary of its first episode, here’s a look back at Wilson’s journey and how his show became a platform that propelled other artists forward.

Clerow Wilson Jr. was born in 1933. His mother left his father, him, and his nine siblings when he was seven; as a result, Wilson and a number of his siblings went to foster homes. Wilson joined the Air Force when he was 16 (yes, he lied about his age). Wilson’s natural instincts for entertaining emerged, and his gift for comedy soon saw him sent from base to base to improve morale. Some of his fellow servicemen would describe him as “flipped out” and called him Flip. Wilson would adopt that name and perform under it for the rest of his career.

Flip Wilson on The Ed Sullivan Show from 1970 (Uploaded to YouTube by The Ed Sullivan Show)

After the Air Force and into the early 1960s, Wilson built his comedy brand. He recorded a pair of albums, Flippin’ (1961) and Flip Wilson’s Pot Luck (1964) during this period as he performed in clubs. He also appeared regularly at the Apollo Theater. When Redd Foxx endorsed him to Johnny Carson, it facilitated his entrance onto television. In addition to multiple appearances on The Tonight Show, Wilson would appear on The Ed Sullivan Show, The Dean Martin Show, Here’s Lucy, and more. With the launch of Rowan and Martin’s Laugh-In in 1968, Wilson was billed as a “Regular Guest Performer” through the first four seasons.

Wilson’s growing popularity earned him a shot with his own show. The Flip Wilson Show debuted on September 17, 1970, on NBC. The program incorporated sketches along with music and celebrity guests. Wilson played a variety of recurring characters. Easily the most famous was Geraldine Jones, his take on a modern Black woman from the South. Geraldine turned out to be something of a catchphrase machine, with lines like “The Devil made me do it,” “What you see is what you get,” and “When you’re hot, you’re hot; when you’re not, you’re not” entering the cultural vocabulary.

Flip Wilson on The Midnight Special (Uploaded to YouTube by Midnight Special)

Wilson used the show as a platform for a number of other Black performers. The show included early appearances by the Jackson 5 and welcomed stalwarts like Aretha Franklin, The Temptations, The Supremes, Stevie Wonder, Ray Charles, and more. He also brought on a wide range of other guests, featuring everyone from Johnny Cash to Bing Crosby to Joan Rivers. Musical guests also frequently took part in the comedy bits. Among Wilson’s writers was legendary comic George Carlin, who himself was in the midst of a turn toward more countercultural comedy; Carlin occasionally appeared on the show as well.

In a short period of time, The Flip Wilson Show was one of the most watched programs in America, falling behind only All in the Family in 1971. It was a groundbreaking success, as Wilson became one of the few Black entertainers to be that popular with white audiences as well. The show was also recognized for its overall quality; it won two of eleven Emmy nominations and earned a Golden Globe for Wilson for Best Actor in a Television Series. Wilson’s fame grew, but the network began to resist his demands for a larger salary. As the show went on, ratings dipped (as they did for most prime-time variety shows of the period), and the series was cancelled in 1974.

Eddie Murphy and Jerry Seinfeld discuss the greatness of Flip Wilson and other comics (Uploaded to YouTube by Netflix Is A Joke)

Wilson worked regularly in comedy, television, and film over the following years. In 1983, he memorably hosted Saturday Night Live; he even played Geraldine in a sketch that “revealed” her to be the mother of Eddie Murphy’s hairdresser character, Dion. Wilson headlined the TV show People Are Funny in 1984 and was the lead in Charlie and Co. from 1985 to 1986. His last television appearance was on a 1996 episode of The Drew Carey Show. Wilson passed away from liver cancer in 1998 at the age of 64.

Wilson reached all audiences with his humor and put acts in front of audiences that might not have seen them otherwise. His influence extended into the way Americans talk; even the editing software WYSIWYG is an acronym taken from one of Geraldine’s catchphrases. He earned the admiration of comedians like Redd Foxx and Richard Pryor, worked to get the best facilities for his show, and wasn’t afraid to demand compensation commensurate with running and starring in the #2 show on television. If what we saw was what we got, then we got greatness.

Featured image: Flip Wilson as Geraldine Jones interviews Dr. David Reuben on an episode of The Flip Wilson Show (Wikimedia Commons)

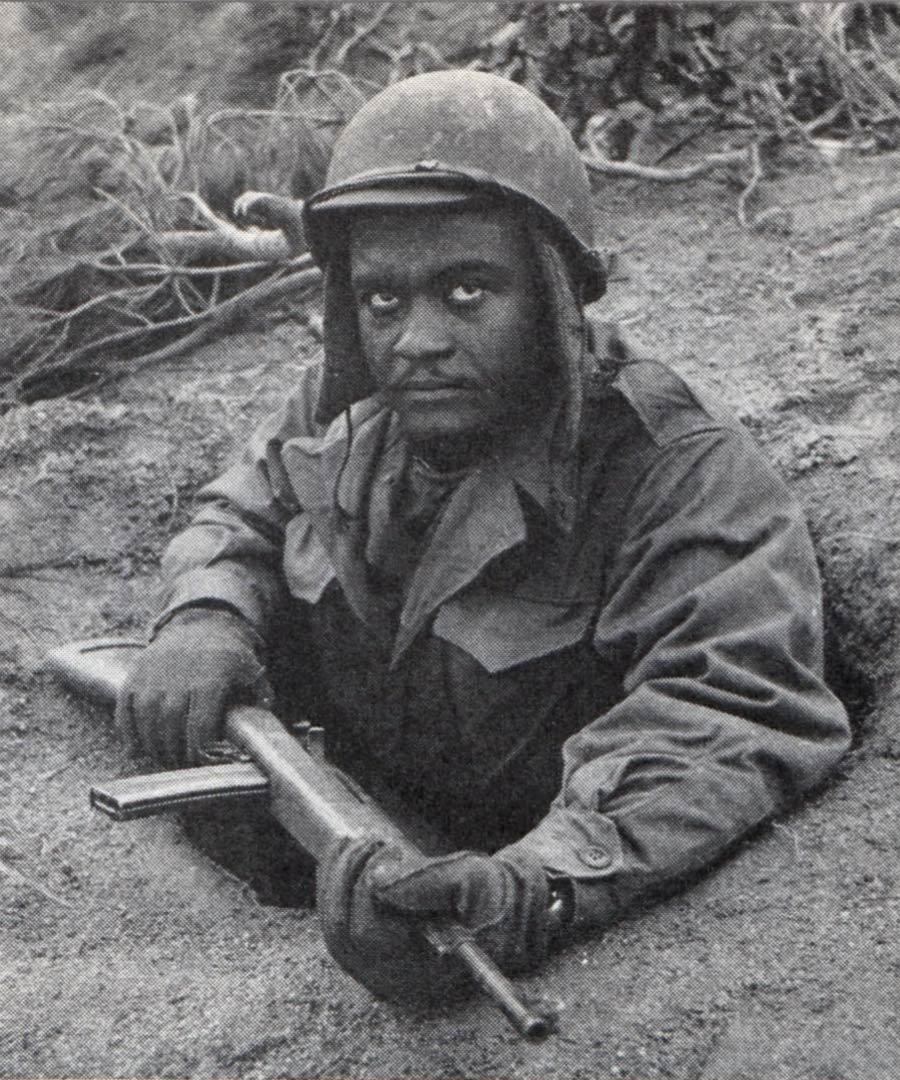

The Rise of the Black Activists

This is the fifth installment in our six-part series, “The Long March on Washington.” In part one, “It’s Our Country, Too,” we looked at the limited wartime opportunities for black Americans in the 1940s. In part two, “Black Neighbors, White Neighborhoods,” we covered integration in neighborhoods throughout the 1950s. In part three, “Black Students, White Schools,” we reported on integration in the classroom. And in part four, “The Deep South Says ‘Never,’” we covered the White Citizens’ Councils campaign to shut down the movement toward integration.

By 1963, the Post was calling it a “revolution.”

In a July 13, 1963, editorial, the authors conceded it was a harsh word. “But there is no denying black forces are drawn up in a battle line that confronts the white man wherever he stands on the principles and practices of segregation.”

Black Americans’ struggle for civil rights had become a revolution, they said, “because the rule of law has failed … the voices of reason have not been heard.” Consequently, the nation had a duty to “accommodate the legitimate aims of this Negro revolution with as little violence and damage to our society as possible.”

Only a few years earlier, the Post’s reporting on civil rights had presented black Americans as generally background players—passive figures quietly enduring centuries of prejudice. All the initiatives seemed to be taken by white politicians or segregation groups like the Klan or White Citizens’ Councils.

But that changed in 1960, as black activists became the protagonists in their own history. As Ben Bagdikian wrote in his 1962 Post article, “Negro Youth’s New March on Dixie,” the country was seeing “the first generation of American Negroes to grow up with the assumption, ‘Segregation is dead.’” And now this new generation had launched a broad offensive in the fight for civil rights.

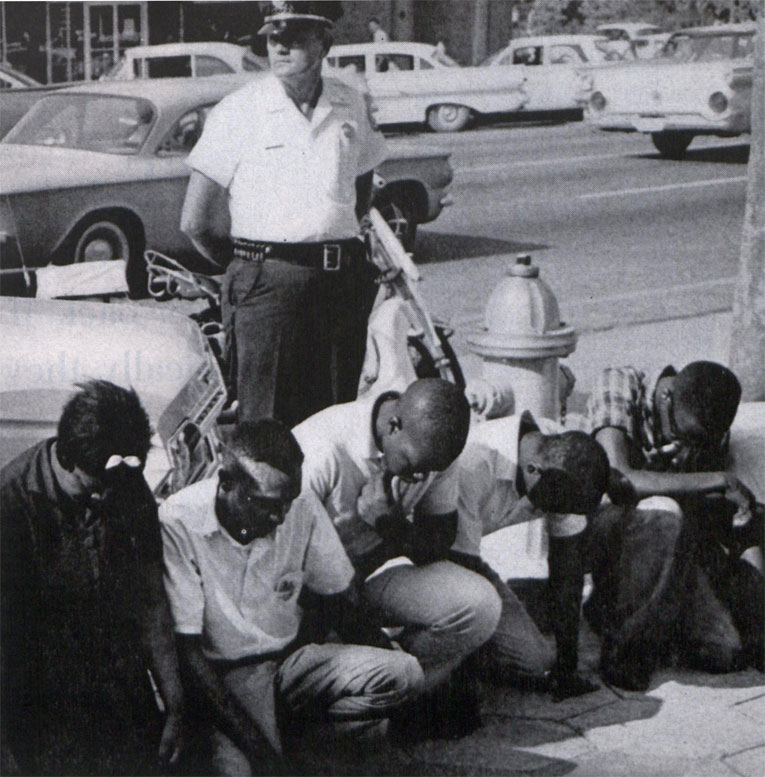

It began with the sit-in, a form of protest that had been sporadically used since the 1940s. The sit-ins were staged at the lunch counters of drug stores and ice cream parlors, where black men and women would take seats in areas reserved for whites only. They would ask for service and, of course, be refused. They would then remain in their seats, waiting to be served, until the store closed or they were arrested.

In February 1960, four students sat in the whites-only section of a lunch counter inside the Greensboro, North Carolina, Woolworth’s store. They were refused service, as expected. When the store closed that night, they left peaceably. The next day they returned along with 16 more protestors, all of who were refused service. On the third day, 60 protestors showed up. On the fourth day, 300 protestors crowded into Woolworth’s to join the daily sit-in. White customers began avoiding the lunch counter and the store’s business declined. Eventually the store’s owners relented and ended segregated service. The first black customer at the Greensboro Woolworth’s was served on July 25, 1960.

1963 © SEPS

Bagdikian was impressed with the way the black community joined into this activism. In Orangeburg, South Carolina, for example, when students were refused service at a lunch counter, 25 other students from a local college protested. “When their college threatened to expel the students, 500 others marched downtown. When the city said it would arrest all demonstrators, 1,400 paraded silently on City Hall.”

By the first anniversary of the Greensboro sit-in, black protestors had staged 48,000 demonstrations in seven Southern states.

At the same time, a new campaign to help Southern blacks register to vote drew volunteers from across the country. Harvard doctoral student Robert Moses told Bagdikian, “I saw a picture in The New York Times of Negro college students ‘sitting in’ at a lunch counter in North Carolina. The students in that picture had a certain look on their faces—sort of sullen, angry, determined. Before, the Negro in the South had always looked on the defensive, cringing. This time they were taking the initiative. They were kids my age, and I knew this had something to do with my own life. It made me realize that for a long time I had been troubled by the problem of being a Negro and at the same time being an American. This was the answer.”

Moses, then a Ph.D. candidate at Harvard, was one of many black Americans heading south to coach Southern black voters on ways to pass their state’s registration tests. He wound up in Liberty, Mississippi, where 5,000 black voters lived but only one was registered to vote.

While he was committed to non-violent means, his opponents weren’t. On August 29, 1961, Bagdikian reported, “Moses was struck down by a cousin of the local sheriff and beaten on the head until his face and clothes were covered with blood.” A week later, one of his colleagues was kicked to semi-consciousness. A month later, another was shot dead.

The following year, black Americans made a further advance against segregated institutions. After a long fight in the courts, James Meredith enrolled at the University of Mississippi, becoming its first black student. The night he arrived at the university, guarded by U.S. marshals, the campus exploded in a riot. More than 28 marshals were shot and 160 were injured. Two men, a student and a French reporter, were shot and killed, and 200 people were arrested.

But Meredith, like Moses, was undeterred by the violence. “In the past, the Negro has not been allowed to receive the education he needs. If this is the way it must be accomplished, and I believe it is, then it is not too high a price to pay.”

He believed he was working toward a future in which black Americans were fully integrated into society. In the past, he said, they had only regarded themselves, and their accomplishments, in relation to other blacks. “That’s not good enough. We have to see ourselves in the whole society. If America isn’t for everybody, it isn’t America.”

Coming Next: The Dangerous Doctor King

The Deep South Says ‘Never’

This is the fourth installment in our six-part series, “The Long March on Washington.” In part one, “It’s Our Country, Too,” we looked at the limited wartime opportunities for black Americans in the 1940s. In part two, “Black Neighbors, White Neighborhoods,” we covered integration in neighborhoods throughout the 1950s. In part three, “Black Students, White School,” we reported on integration in the classroom.

“With all deliberate speed” was how the Supreme Court wanted American schools to integrate their classrooms. But in the years following their Brown v. Board of Education decision, little action had been seen.

By 1957, about 330,000 black children had been admitted to formerly all-white schools, but another 2,475,000 still awaited integration.

The Post looked into the reasons for such little progress in a five-part series, “The Deep South Says Never” by John Bartlow Martin (June-July 1957), which it proudly called “the most exhaustive and penetrating look at the problems of integration yet published in an American periodical.”

The Supreme Court’s decision had outraged many Americans in Southern states with segregated schools. Southern politicians spoke of protests, legal appeals, and outright refusal to comply. But there was yet no organized effort to oppose the federal mandate.

Then, one night in 1953, Robert Patterson, a farmer in Indianola, Mississippi, attended a meeting at his children’s school where he heard officials announce their all-white school would have to admit black students. Patterson was stunned. As he later wrote in a widely distributed letter to “fellow Americans,” “I gathered my children and promised them that they would never have to go to school with children of other races against their will.”

He began seeking like-minded citizens who could build public opposition to the federal order. When he and a handful of associates called a town meeting to address integration, he told Martin, “Everybody of any standing was there.” They agreed to form the Indianola Citizens’ Council, which started a movement that swept across the South to solidify resistance to integration.

At first, the Council aroused little interest among Southern segregationists because the federal government did not try to enforce integration. During this time, Patterson and his friends traveled to other towns, speaking to the towns’ service clubs of the need to organize opposition to integration. Soon, Citizens’ Councils were springing up in adjoining states.

The Councils didn’t content themselves with merely building public support for segregation. They were ready to apply financial influence to silence the voices for integration. As a council member told Martin, “The white population in this county controls the money. … We intend to make it difficult, if not impossible, for any Negro who advocates desegregation to find and hold a job, get credit, or renew a mortgage.”

The Council began applying its influence in June 1955, when black residents in five Mississippi cities petitioned local school boards to admit their children to all-white schools.

In Yazoo City, Mississippi, for instance, the Citizens’ Council published the names and addresses of all petitioners in the local paper. Roy Wilkins of the NAACP told Martin, “There were about fifty-three signers originally, and when [the Council] got through, only two signatures remained on it. One of them is living by helping his wife sell mail-order cosmetics—couldn’t get any work in town. One man had been a plumber for twenty years in Yazoo City, but he lost his business as soon as his name was in the paper.

“Wholesalers refused to supply a Negro grocer who had signed the petition, and a banker told him to come and get his money. He took his name off the petition, but it did no good. He left town.”

News that the petitions in all five cities were withdrawn encouraged the growth of segregationist groups in other states. By the end of 1955, one survey showed at least 568 local pro-segregation organizations in the South, claiming a membership of 208,000.

Council members were motivated by several reasons, though none admitted racism was among them. Some believed segregation was necessary to keep black men away from white women. (Patterson wrote protectively of “the loveliest and the purest of God’s creatures, the nearest thing to an angelic being that treads this terrestrial ball is a well-bred, cultured Southern white woman or her blue-eyed, golden-haired little girl.”)

Not all southerners supported these extremists. One Southerner told Martin he thought Council members were unintelligent and obsessed with interracial sex. “I once asked a council member, ‘What is your organization’s program?’

“He said, ‘To make people aware of the problem.’

“‘Do you think there is anybody south of the Mason-Dixon’s line that isn’t aware of it?’

“‘No.’

“‘Then what do you do at your meetings?’

“‘Well, we discuss the situation, discuss segregation.’

“‘It must get a little boring.’

“‘Well, yes, but we always get around to miscegenation.’”

Council members also felt they were fighting communism by opposing civil rights for blacks. Integration, they said, was a communist plot to stir up resentment in black Americans, who would rise up to destroy society. Patterson wrote, “If every southerner who feels as I do, and they are in the vast majority, will make this vow (to prevent integration), we will defeat this communistic disease that is being thrust upon us.”

What Patterson couldn’t have known was that the revival of aggressive bigotry in the South was helping to ignite a force in the black community. Black Americans were no longer waiting for the federal government to secure their civil rights, but had started taking action themselves.

Coming Next: The Rise of the Black Activists

‘It’s Our Country, Too’

We begin a new series on “The Long March on Washington” by looking at a 1940s article about wartime opportunities for black Americans.

Popular history tells us that the March on Washington began on the morning of August 28, 1963, when more than 200,000 Americans gathered at the Washington Monument and progressed to the Lincoln Memorial.

But the March actually began 22 years earlier, as America was being drawn into World War II. To prepare its defenses, the government had brought back the draft and placed large orders for armaments with the nation’s manufacturers. Young men could choose to enlist with the service of their choice, or take advantage of lucrative defense work—if they were white. But few wartime opportunities existed for black men.

As Walter White, secretary of the NAACP, wrote in the Post, “The Negro insists upon doing his part, and the Army and Navy want none of him.”

White’s article, “It’s Our Country, Too” (December 14, 1940), cited numerous instances in which the military turned away qualified black men. For example, when a skilled black pilot applied to the Army Air Corps, he was flatly told by the recruiting officer, “There is no place for a Negro in the Air Corps.”

A black enlistee with a degree in pharmacology was told, “We’re not going to have any black pharmacists in the Army.” A black volunteer at a southern recruiting station was told it was for “whites only” and, when he questioned this policy, was savagely beaten before being thrown out onto the street.

At the time of his writing, White said, the regular Army had just five black officers. Three of them were chaplains. However, the Army readily accepted black men to serve as cooks, truck drivers, sanitation workers, and grooms in cavalry stables.

If a black man applied to the Navy, White said, he ran into even greater resistance. “Until [World War I] it was possible for Negroes in the Navy to attain the rank of petty officer. Nowadays, they are permitted to enlist only as menials. They can rise only to the position of officers’ cook or steward.” An assistant to the Secretary of the Navy wrote that this policy “was adopted to meet the best interests of the Navy and the country, [and] the men themselves.”

As for the marines of 1940, White wrote, “no Negro has ever served, either as an officer or an enlisted man, in the Marine Corps

Meanwhile, employment opportunities were opening up in factories that had received large government contracts to produce weapons. Black Americans found most of these opportunities closed to them. White reported that skilled black workmen found it impossible to gain employment in shipyards where unions only permitted hiring “members of the white race.”

An airplane plant in Nashville, Tennessee, planned to employ more than 7,000 men, but a company representative told White, “I am not certain at the present time how many colored people will be employed in our plant. As far as I know, there will be very few. There possibly will be some porters and truckmen.”

Discrimination wasn’t only found in the South, however. White reported that an airplane manufacturer in New England told the federal employment offices that “Negro applicants should not be sent, and that if they were sent they would not be hired.”

In September of 1940, White and A. Philip Randolph, president of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters, met with President Franklin D. Roosevelt to find ways to end segregation in the military and industry. Roosevelt agreed to create more opportunities for black servicemen in every branch of the service, including combat units. But he felt he couldn’t integrate black and white soldiers in the same regiments.

Randolph pleaded for more opportunities for blacks in defense plants, but Roosevelt was reluctant to use his office to end discrimination. So, early in 1941, Randolph proposed staging a large-scale protest. Setting up a March on Washington Committee, with offices in 18 major cities, he planned to bring thousands of black Americans to the capital. They would march down Pennsylvania Avenue to bring attention to the discrimination in defense plants.

Now it was Roosevelt’s turn to need a favor; he asked Randolph to call off the march. The president felt the protest would diminish his efforts to build national unity for the impending war. In the end, Randolph called off the march after the president agreed to issue an executive order prohibiting discrimination in any plant with a federal defense contract.

The armed forces remained segregated for the duration of the war. Black men distinguished themselves in several infantry, cavalry, and artillery divisions, as well as two marine divisions and the 332d Fighter Group, the Tuskegee Airmen. Finally, in 1948, President Harry S. Truman ordered the military to integrate.

Randolph’s challenge marked the beginning of a new era in the struggle for civil rights. For the first time, a black leader had negotiated from a position of strength because thousands of black Americans were ready to support massed action.

Coming Next: Panic in White Neighborhoods

President Obama to Speak at NAACP

A Proud Moment in a Long Struggle

President Obama will be in New York on July 16 speaking to a crowd of 10,000 people. While he has addressed much larger groups, rarely has he spoken on such a significant occasion: America’s first black president will be giving the keynote speech at the 100th birthday celebration of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP).

The NAACP was formed in 1909 to address a rising opposition to civil rights. Racism in America was discarding its subtlety, coming out in the open, and making a new bid for power. Southern legislators had enacted new laws that made it difficult, if not impossible, for black Americans to vote. Racial tensions ignited race riots, and more were coming.

Dr. W.E.B. DuBois edited the NAACP’s magazine, The Crisis, and helped frame the association’s goal:

“To promote equality of rights and to eradicate caste or race prejudice among the citizens of the United States; to advance the interest of colored citizens; to secure for the impartial suffrage; and to increase their opportunities for securing justice in the court, education for the children, employment according to their ability and complete equality before law.”

The early years were daunting and Washington extended little sympathy for the cause. The NAACP addressed the need to end official segregation, promote black men to officers in the military, and oppose the rising enrollment in the Ku Klux Klan. The effort met consistent opposition from southern legislators who blocked federal legislation against lynching.

Halfway through its first century, the NAACP was confronting racism as virulent as ever. Black Americans were achieving some of their goals, but they were also being accused of seeking their rights too aggressively.

Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.

Nov. 7, 1964

In the November 7, 1964, Post, Dr. Martin Luther King addressed this issue directly in his article, “Negroes Are Not Moving Too Fast.”

“Among many white Americans who have recently achieved middle-class status or regard themselves close to it, there is a prevailing belief that Negroes are moving too fast and that their speed imperils the security of whites. Those who feel this way refer to their own experience and conclude that while they waited long for their chance, the Negro is expecting special advantages from the government. It is true that many white Americans struggled to attain security. It is also a hard fact that none had the experience of Negroes. No one else endured chattel slavery on American soil. No one else suffered discrimination so intensely or so long as the Negroes. In one or two generations the conditions of life for white Americans altered radically. For Negroes, after three centuries, wretchedness and misery still afflict the majority.

“Anatole France once said, ‘The law, in its majestic equality, forbids all men to sleep under bridges—the rich as well as the poor.’ There could scarcely be a better statement of the dilemma of the Negro today. After a decade of bitter struggle, multiple laws have been enacted proclaiming his equality. He should feel exhilaration as his goal comes into sight. But the ordinary black man knows that Anatole France’s sardonic jest expresses a very bitter truth. Despite new laws, little has changed in his life in the ghettos. …

“Charges that Negroes are going ‘too fast’ are both cruel and dangerous. The Negro is not going nearly fast enough, and claims to the contrary only play into the hands of those who believe that violence is the only means by which the Negro will get anywhere. …

“A section of the white population, perceiving Negro pressure for change, misconstrues it as a demand for privileges rather than as a desperate quest for existence. The ensuing white backlash intimidates government officials who are already too timorous, and, when the crisis demands vigorous measures, a paralysis ensues. …

“Our nation has absorbed many minorities from all nations of the world. In the beginning of this century, in a single decade, almost nine million immigrants were drawn into our society. Many reforms were necessary—labor laws and social-welfare measures— to achieve this result. We accomplished these changes in the past because there was a will to do it, and because the nation became greater and stronger in the process. Our country has the need and capacity for further growth, and today there are enough Americans, Negro and white, with faith in the future, with compassion, and will to repeat the bright experience of our past.”

The NAACP has no reason to close operations this year. There is, alas, still more work ahead. However, we hope they, and the country, savor the moment when President Obama shares the podium with America’s first black secretary of state, Colin Powell, and our first black attorney general, Eric Holder. America should be very proud of this organization and the long dedication of its generations of members.