Tiger Woods and More Triumphant Sports Returns

As Tiger Woods steps onto the grass at The Masters this week, the eyes of the sports world are upon him. Woods, returning from what many had thought was a career-ending accident, has defied the odds before. In 2019, Woods won The Masters after an 11-year drought at major tournaments. Could Woods make another thrilling return? In that spirit, here are five other returns by athletes that should never have been counted out.

Before we look at the Big Five, here’s a Bonus Two-for-One Special:

Bonus: Magic Johnson and Larry Bird

The Best of the Dream Team (Uploaded to YouTube by Olympics)

In 1992, Larry Bird of the Boston Celtics was on the verge of retirement. Plagued by back problems, he’d had a disc removed, missed 37 games during that season, and was headed out the door. His great friend and nemesis, Magic Johnson of the L.A. Lakers, had retired in 1991 after being diagnosed as HIV-positive. However, the two had a chance for one last run together: the 1992 Olympics in Barcelona. Joining one of the greatest athletic teams ever assembled, Bird, Magic, and the rest of Team USA stormed their way to a gold medal. For basketball fans that had watched the pair battle from the 1979 NCAA Finals and through the entire 1980s in the NBA, well, that’s why they called it “The Dream Team.” While Bird did retire after the Olympics, Magic returned to the NBA as a player in 1996, helping the team get fourth seed in the playoffs. After the Lakers lost to the Rockets, Magic retired for good.

5. George Foreman

George Foreman in 1973 (Photo by Bert Verhoeff via Wikimedia Commons; Creative Commons CC0 1.0 Universal Public Domain Dedication)

One of the best to ever lace up a pair of boxing gloves, George Foreman took gold in the 1968 Olympics as a heavyweight. Foreman went on to knock out an undefeated Joe Frazier to become heavyweight champ in 1973. His title reign came to an end at the hands of Muhammad Ali at 1974’s legendary “Rumble in the Jungle.” Foreman retired in 1977. After spending several years as a minister, Foreman came back to boxing in 1987. In 1994, the 45-year-old Foreman knocked out Michael Moorer to become the unified heavyweight champion. He remains the oldest man to be heavyweight champion.

4. Bethany Hamilton

This Iz My Story (Uploaded to YouTube by Bethany Hamilton)

Bethany Hamilton excelled at surfing from an early age. An avid competitor by age eight with sponsorships by age ten, Hamilton had her eyes on big titles. However, in 2003 when she was 13, the unthinkable happened. During a surfing excursion, a 14-foot long tiger shark bit off Hamilton’s left arm below her shoulder. It was a trauma that would have crushed most people, but not Hamilton. She returned to the waves a mere month after the incident. In 2005, she took first in the NSSA Nationals and won her first pro tournament in 2007.

3. Mario Lemieux

Lemieux Scored 100 Points 10 Different Times (Uploaded to YouTube by NHL)

There’s no debate about the greatness of Mario Lemieux. He’s widely regarded as one of the greatest hockey players ever. Lemieux debuted for the Pittsburgh Penguins in 1984 and quickly became a star. He was Rookie of the Year and was only outscored in his sophomore season by Wayne Gretzky. Though Lemieux would struggle with back injuries, he was a major force in the NHL as one of the sport’s biggest scorers. In 1993, “Super Mario” was diagnosed with Hodgkin lymphoma. Undeterred, he continued to play, even on the same day as radiation treatments. Incredibly, he won the scoring title that year. Though he continued to play at a high level, the years of back problems and his earlier battle with cancer factored in to Lemieux’s decision to retire in 1997. With the Penguins facing money trouble, Lemieux came in with a plan to become the team’s majority owner. He helped turn things around the ledger, and then did something more incredible: he returned to the ice. Lemieux played from 2000 to 2006, ending his career with dozens of records and an Olympic gold medal from 2002.

2. Michael Jordan

The Best of Jordan’s Playoff Games (Uploaded to YouTube by NBA)

For Michael Jordan, an NBA championship wasn’t a question of “if,” but a question of “when.” Joining the league in decade dominated by the Celtics and the Lakers, Jordan turned around the fortunes of the Chicago Bulls. He led the team to a finals win in 1991, and then again in 1992 and 1993. Tragically, Jordan’s father, James Jordan, Sr., was murdered by carjackers in July of 1993. That October, Jordan retired, citing his father’s death, a loss of desire to play, and general exhaustion. After detour to play minor league baseball, Jordan issued a two-word press release (“I’m back”) and returned to the NBA in March 1995. He lifted the struggling Bulls into the playoffs, where they lost to the Orlando Magic. As the meme goes, Jordan took that personally. Over the next three seasons, Jordan led the Bulls to championships in 1996, 1997, and 1998, cementing his status as one of, if not the, greatest to ever play the game.

1. Muhammad Ali

Muhammad Ali – The Greatest of All Time (Uploaded to YouTube by Nonstop Sports)

How could The Greatest now be #1? Muhammad Ali’s life was defined by battle. Whether it was taking the Olympic gold medal in Rome in 1960 or taking his draft evasion conviction all the way to the Supreme Court, Ali never backed down from a challenge. After becoming champion in 1964, Ali voiced his opposition to the war in Vietnam and proclaimed his status as a conscientious objector. His titles were stripped, and Ali fought the decisions in court. The conviction was overturned in 1971 and Ali found himself in the position to challenge Joe Frazier for the heavyweight title. Both men were undefeated going in, but it was Ali that left with his first professional loss. Of course, that didn’t mean that Ali was done. He faced Frazier again in 1974, defeating his old rival to get a shot at the then-current champ, George Foreman. At the “Rumble in the Jungle,” Ali knocked out Foreman to retake the title. He would eventually retire in 1981, a three-time heavyweight champion

5-Minute Fitness: No Bag or Gloves Required

“Anyone can utilize shadowboxing for overall strength, balance, and agility,” says Kristy Rose Follmar, head coach at Indianapolis-based Rock Steady Boxing, a boxing-style program to benefit people with Parkinson’s.

Shadowboxing

1 Stand with feet shoulder-width apart and dominant foot forward. Bend knees slightly and hold fists between

2 Punch slowly for 30 seconds, alternating arms and breathing out with every punch. Switch lead leg and repeat. When feeling confident that you are ready to speed up, continue to Step 3.

3 Punch faster, alternating arms and keeping your body tight and steady. You can use a mirror to make sure you’re keeping your body still while you punch. Work up to punching for 1 minute. Switch lead leg and repeat. Ready for more? Rest for 30 seconds, then repeat Step 3 for 2 rounds or more! Too hard? Do Steps 1-3 while seated.

A Black Champion’s Biggest Fight

The prize fight held on July 4, 1910, in Reno, Nevada was hailed “the Fight of the Century.”

In fact, it was just part of a fight that has been as long as our country’s history.

On that date, African-American champion Jack Johnson was defending his title against Jim Jeffries, as well as defending his race against a racist opponent. His victory detonated America’s first national race riot.

Seven years earlier, Johnson had won the “Colored Heavyweight Championship of the World.” He then achieved what no black athlete had done before: secured a chance to take a championship title from a white athlete. He boxed and defeated Canadian Tommy Burns for the world heavyweight title.

Johnson’s win challenged the racial superiority assumed by many white Americans. Sports writers and white fans called out for a “great white hope,” a heavyweight boxer who would re-assert white supremacy in the ring. When former champion Jim Jeffries agreed to fight Johnson, he publicly said his intention was “to win the title back for the white race.” And “I am going into this fight for the sole purpose of proving that a white man is better than a Negro.”

The need to beat Johnson was made even more urgent because of his personality. He was flamboyant, proud, lived lavishly, drove recklessly, and had affairs with white women. So when he climbed into the ring in Reno, Johnson could sense waves of resentment rising from the crowd of 22,000 spectators. Jeffries even refused to shake his hand before the match.

Jack Johnson vs James J. Jeffries (uploaded to YouTube by Classic Boxing Matches)

Twenty-five years later, in an article from the August 3, 1935, issue of the Post, Jeffries said he trained intensively for a year-and-a-half before the match. He got back into shape and dropped his weight from 285 to 220. But just days before the match, he caught a severe case of dysentery that kept him from putting up his best fight. But there was no talk of illness in the days following the match. Then, Jeffries said, “I could never have whipped Johnson at my best. I couldn’t have hit him. No, I couldn’t have reached him in 1,000 years.”

White boxing fans who had made the match a contest of the black and white races felt humiliated and angry. They took the fight from the ring into the streets of American cities.

It was not a good year for race relations in America. At least 67 black Americans were lynched in 1910. The Keokuk, Iowa, newspaper that carried the news of Johnson’s victory also featured a front-page story about the black population of Charleston, MO, fleeing the city after two black men were lynched in the street by a gang of white men.

That same paper reported race riots broke out in 50 American cities following the news of Jeffries’ defeat. In New York, according to the Daily Gate City, 11 different racial brawls were reported on the night of the Fourth. Crowds, the paper reported, tried to burn tenements in black neighborhoods. African Americans were dragged from trolley cars in several locations by white rioters and beaten.

In Columbus, Ohio, white spectators repeatedly set upon 400 black men and women who were marching in a parade celebrating Johnson’s win.

A black man buying a newspaper was accosted by a mob, who demanded he tell them what he thought of the fight. “I am neutral,” the man replied. “Let’s kill the [racial epithet],” someone said and the gang approached him. He pulled a knife and held them off until the police arrived.

One reason for the attacks was the fear that African Americans would abandon the deference they were expected to show for the racial majority. A New York Times editorial written two months before the fight stated, “If the black man wins, thousands and thousands of his ignorant brothers will misinterpret his victory as justifying claims to much more than mere physical equality with their white neighbors.”

For some white fans, this championship bout ruined the sport. Eight years later, a humorous note in the October 6, 1923, Post observed, “The papers have been full of the news of prize fights. There must be some mistake about it. As nearly everybody knows, the boxing game in this country died when Jack Johnson whipped Jim Jeffries. It was repeatedly and authoritatively stated there never would be another prize fight.”

Five years later, Johnson was defeated by Jess Willard, a white boxer. Many white boxing fans were exultant. The book Jess Willard: Heavyweight Champion of the World described the aftermath: A sports writer for the St. Louis Times reported, “thousands and thousands of fight fans as well as thousands and thousands of ordinary citizens flooded the downtown streets waiting for the decision.” When they heard Willard had won, “they acted like crazy people.” According to the New York Tribune, the news prompted “respectable business men [to pound] their unknown neighbors on the back and [caper] about like children.”

In a May 8, 1915 editorial, the Post observed, “Critics seem quite unanimously of opinion that this event… is a thing of high importance to the white race. They seem, also, quite unanimously of opinion that Mr. Johnson would have beaten his white antagonist handily if he had not for some years followed an injudicious and deleterious mode of living. We are puzzled to discover a cause for racial pride in the circumstance that a white man was able to whip a black man only after the latter had impaired his constitution by dissipation.”

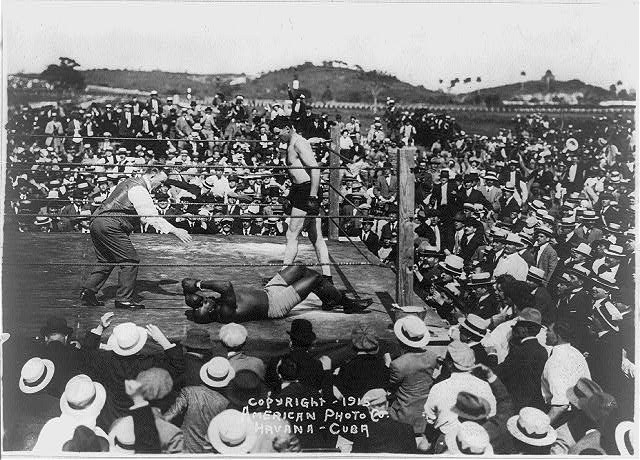

Three years before the match with Willard, while he was still champion, Johnson had been arrested and charged with violating the Mann Act for driving his white girlfriend “across state lines for immoral purposes.” Johnson fled the country to escape prosecution, which was why his fight was Willard was held in Havana, Cuba.

For years, the rumor persisted that Johnson threw the match, agreeing to take a fall in return for having the charges dropped. Johnson himself contributed to the stories, insisting that he had pretended to be knocked out as part of a deal with the government to drop its charges against him.

But writing for the Post in the April 4, 1925, issue, former heavyweight champion James J. Corbett said of the Johnson-Willard fight, “I was quite near the ringside and watched Johnson closely, and I am morally certain he would never have gone through twenty-six long rounds had the result been prearranged; he would have chosen an earlier round to flop in.” Agreeing with Corbett, Willard said, “If he was going to throw the fight, I wish he’d done it sooner. It was hotter than hell out there.”

But the rumor never stopped hounding Johnson. In the 1940s, having spent a year in jail for the Mann Act violation, he was reduced to boxing in private events. He then got the idea for another way to raise cash, and went to the editor of the boxing magazine Ring, Nat Fleischer.

Fleischer knew Johnson. He had been at ringside when Johnson fell. According to a March 16, 1946 Post interview with Fleischer, “Johnson went down under big Jess Willard’s blows in the twenty-sixth round, rolled over on his back and raised an arm to shield his eyes from the tropical sun as he was counted out.” The arm-raising incident was cited as proof that Johnson had gone into the tank for Willard. Fleischer, convinced that the bout was fought on its merits, always argued that even a semiconscious man would instinctively try to shield his eyes from the blinding rays of the sun.

Despite Fleischer’s certainty of Johnson’s integrity, the Post reported that, “Johnson came to Fleischer with a signed confession stating that he had ‘gone into the water’ for Willard. Nat paid him $250 for it, after the ex-champion had signed an agreement giving him the exclusive rights to publish the story. Fleischer put the document in his safe, where it has since gathered mildew. Fleischer says Johnson has since tried to buy back the ‘confession,’ because he can get a better price for it elsewhere.”

Nat refused to sell. He didn’t believe a word of it, and chose not to publish the confession to protect a boxer, and a sport, that he revered.

In 2018, 72 years after his death, Johnson finally received a presidential pardon for his violation of the Mann Act.

Featured image: Jack Johnson and James Jeffries in 1910 (Wikimedia Commons / Library of Congress)

Cartoons: Boxing Banter

Irwin Caplan

October 19, 1946

Mary Gibson

October 5, 1946

Adolph Schus

November 2, 1946

Chon Day

May 1, 1948

Salo Roth

March 27, 1948

George Wolfe

February 19, 1944

Jack Tippit

February 11, 1961

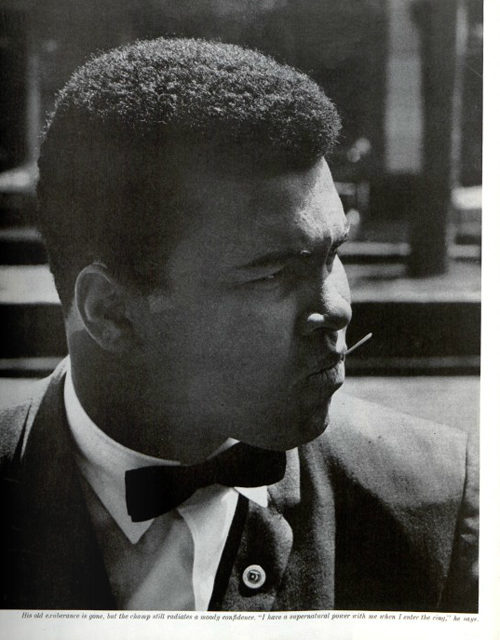

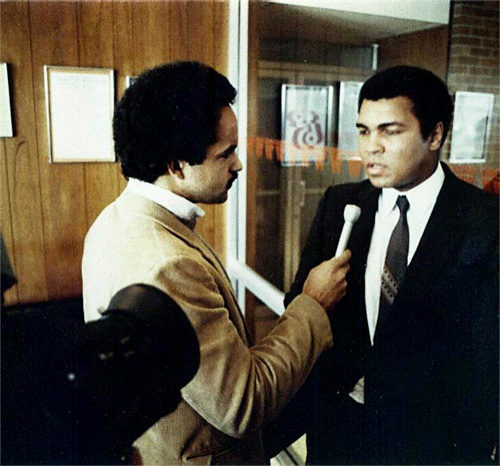

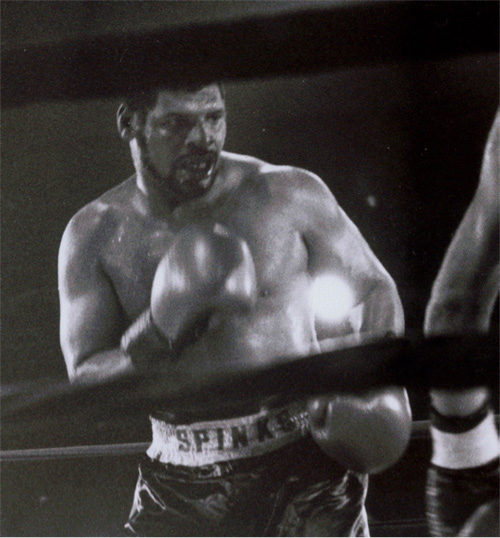

40 Years Ago: The Greatest Wins One More Time

Leon Spinks stunned the world on February 15, 1978. The 1976 Olympic Gold medalist for Boxing, Spinks got the opportunity to face “The Greatest,” Muhammad Ali. Ali had just come off of a widely praised victory over Earnie Shavers, and chose Spinks as his opponent partially due to a desire to avoid Ken Norton, whom he’d already fought three times. Spinks amazed everyone by beating Ali in a split decision in only his eighth professional fight.

A number of factors led to Ali’s loss. He had already flirted with retirement in 1976 before returning the next year to beat Alfredo Evangelista. He was out of shape. And he underestimated his opponent. He wouldn’t make that mistake again. Ali got his chance for some payback when Spinks agreed to a rematch for the World Boxing Association heavyweight title in New Orleans on September 15, 1978.

Despite the fact that he’d lost in February, Ali was still considered the favorite. The wildly charismatic and controversial boxer had managed to delight and infuriate the American public throughout his career. When The Saturday Evening Post profiled him in 1964, one significant focus of the piece had been his conversion to Islam. At time of the Spinks fights, Ali had recently undergone an additional religious journey, turning from the Nation of Islam in 1975 and embracing Sunni Islam beliefs.

On the night of September 15, it was safe to say that the world was watching. ABC had the rights to the fight, and they broadcast it to an estimated 90 million people in the U.S. Around the world, the total audience for the bout was a record 2 billion people. Ali arrived in shape and ready to throw hands. Spinks found himself fighting a different Ali. The man he’d fought in February had been a bit sluggish; this Ali focused on footwork and jabs, locking up Spinks up whenever he came in too close (in fact, the referee stripped the fifth round from Ali in favor of Spinks because of Ali’s excessive holding).

The fight went the distance, and Ali won in a unanimous decision by the judges. It was his third WBA heavyweight championship, making him the first man to accomplish that feat. Ali sent an official letter to the WBA in June of 1979 to announce his retirement, but he ended up competing in two more fights. He would lose once to Larry Holmes in 1980, and again to Trevor Berbick in 1981. After that, he hung up his gloves for good. After Ali, only one other American boxer has had three WBA heavyweight reigns, fellow Olympian Evander Holyfield.

Spinks didn’t have a stellar career after the fight with Ali. He himself was beaten by Holmes in 1981, though Holmes would later drop the title to Leon’s brother, Michael Spinks, in 1985, making them the only brothers to be heavyweight champs. Leon Spinks tried to shed weight and box as a cruiserweight to little success. After that, he became a professional wrestler for Frontier Martial-Arts Wrestling in Japan; he took that the title in 1992, making him the only person to be both an American boxing and professional wrestling champion in his career. Leon and Michael Spinks, like Ali, have been inducted into the Nevada Boxing Hall of Fame. Leon’s son, Cory, was also a boxing champ in the welterweight and IBC junior middleweight divisions. Today, Leon Spinks lives in Las Vegas, Nevada.

As for Ali, his later years focused on humanitarian projects and philanthropy. Though he began to suffer from the effects of Parkinson’s Disease, he kept a high public profile. A Gold medal-winning Olympic boxer himself (he earned the Light Heavyweight medal in Rome in 1960), he was invited to light the Olympic flame at the Atlanta games in 1996. After years of declining health, Muhammad Ali died on June 3, 2016 at age 74, leaving behind the vibrant legacy of a larger-than-life personality that couldn’t help but set new standards in his sport.