Saturday Evening Post History Minute: The Evolution of the Grocery Store from Corner Market to Colossus

See all of our History Minute videos.

Featured image: Store clerk in Minneapolis (Library of Congress)

Ask the Manners Guy: Take This Job and Love It

I accepted a job offer, then two weeks later my dream job called me back. I would hate to leave my new company hanging, but I really want this other job. Is there an acceptable way to burn this bridge?

Definitely accept the offer for your dream job, but get a confirmation in writing. There’s no pleasant way to quit a job you just started, but it’s best to be straightforward. Get your things together at your desk and go tell your boss. You can ask them for ways you can be helpful before you leave, but the odds are that you’ll be walking straight out of the building. Don’t feel guilty, though; you should always choose your career interests over your company’s.

The Manners Guy is a former bartender who knows his way around awkward social situations. Send your questions to [email protected].

This article is featured in the January/February 2020 issue of The Saturday Evening Post. Subscribe to the magazine for more art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

Featured image: Shutterstock

The Problem with the Mindfulness Movement

You leave work late and drive home in rush-hour traffic, listening to a podcast with a climate scientist explaining the gloom-and-doom scenario that awaits us all. When the traffic jam finally breaks up, you get your economy car up to speed, and — Bam! — you hit the pothole you’ve been avoiding for months, piercing a tire. When you finally make it back to the small apartment you pay too much money for, you check your mail to find a bill from your recent hospital visit just shy of your $2,000 deductible. You close yourself into a quiet room and open the Aura app on your smart phone that guides you through a focused breathing meditation to cultivate mindfulness.

Is it working?

Mindfulness, a practice taken from Buddhism, has steadily popularized as a remedy for daily stresses over the last few decades. Big CEOs, therapists, and scientists have testified for the “life-changing” results of looking inward, but some thought leaders say it’s only part of a wider trend of individualizing societal problems.

When I first spoke to Dr. Ronald Purser, he read my puzzled mind, saying “You’re probably thinking I seem awfully anti-capitalist for a management professor.” Purser, a professor of Management at the College of Business at San Francisco State University, is also an ordained Zen Dharma teacher in the Korean Zen Taego Order. He has been publishing papers on management and organizational change through Buddhist or ecological lenses for decades. His most recent book, McMindfulness, is a critique of the rising industry around the practice of mindfulness and its corporate proponents: elites cherry-picking Buddhism to offer cold comfort and reinforce individualism.

The Saturday Evening Post: What is the mindfulness movement?

Purser: It’s not a monolith, but I think, in general, we’ve seen how a therapeutic modality gradually morphed into a capitalist spiritually, as I put it. Mindfulness as a therapeutic intervention started with Jon Kabat-Zinn’s work in 1979. It initially offered an alternative intervention for chronic stress and other maladies, but for many years it was confined to hospitals and clinics. Around 2000 to 2005, it became mainstream. This whole process involved slowly growing scientific interest around mindfulness to garner legitimacy. To offer mindfulness as a medical intervention, it really had to be mystified. What I mean by that, is that the explicit connection of mindfulness practice to any kind of Buddhist sources had to be downplayed. Once it was decontextualized from a Buddhist framework — like teachings on ethics and morality, and so forth — it could gain traction in secular audiences, and then entrepreneurship kicked in.

I think it gained a lot of traction after the financial crisis of 2008 because people were overwhelmed by the stresses and anxieties they were facing. Mindfulness offered a convenient respite, a way to turn away from all of the structural and political challenges of our time.

Post: What’s wrong with people practicing mindfulness? Isn’t it a healthy habit?

Purser: There isn’t anything inherently wrong with using mindfulness to de-stress. The problem isn’t that using mindfulness for stress-reduction doesn’t work — the problem is that it does work! But work in the service of whom and for whose interests? For example, just as there is nothing wrong with treating those suffering from depression, the problem is when the diagnosis and dominant narrative is that depression is nothing but a chemical imbalance in the brain. The pharmaceutical industry has a huge financial stake in maintaining and propagating such a narrative that is based on biological reductionism.

Similarly, the mindfulness industry and its proponents have a vested interest in maintaining a narrow way of framing and explaining stress in our society, which also adheres to a reductionist focus on the individual. Whether explicitly or implicitly, it sends the wrong message that the stresses people experience are just inside their own heads, or that their external resources and social conditions don’t matter. People may find that they could be a lot less stressed if they organized around collective resources — by building community, and engaging more politically in solidarity with others in changing our political and economic systems. It’s not an either/or choice, but the mindfulness apologists have chosen the individual to the downplaying of the social and communal dimensions of mindfulness.

This is partly because mindfulness has been embedded in therapeutic culture. This is what the late critical psychologist David Smail called “magic voluntarism:” de-contextualized individuals alone are held responsible for their stress and anguish, regardless of the social and economic milieu in which their lives are embedded. And mindfulness is now a DIY technique that an isolated individual can perform in order to cope with the challenges of modernity.

Post: Is mindfulness related to positive psychology?

Purser: These self-help techniques, to me, all represent a way of rekindling individualism in our society. The neoliberal ethos is alive and well, so these methodologies don’t meet any resistance when it comes to integrating them into our culture. One of the latest fads is “grit” or “resilience,” it’s this notion that all of our success and happiness are just a matter of turning inward and finding our inner resources. They all subscribe to the idea of the autonomous individual, which is separate from the community. It’s a sort of hyper-individualistic way of legitimizing neoliberalism.

Post: Would you say we are experiencing more stress in the current time period than times past? I’m thinking particularly of the turn of the last century and the many accounts of widespread stress in this country as people moved into cities in large numbers, among the many other societal changes.

Purser: In the book, I chronicle the long history of how we got to the discourse of stress that we’re using now. At the turn of the century, there was that strange diagnosis called neurasthenia which was a bizarre diagnosis reserved primarily for upper classes. It was actually a badge of honor. They saw it as the price you had to pay for progress and industrialization. But, certainly, they were going through something. The diagnosis at the time was different than it is now, but I think there’s a parallel there. In both cases, you see the medical community coming in and overlaying the etiology, basically saying that it’s located in the individual.

But I think that we are more stressed. There are statistics on this. Workplace stress is on the rise, as are stress-related diseases. A World Health Organization study that found around $300 billion a year is lost due to stress at work. Part of my critique is that the cure places the burden of responsibility on individuals.

Post: You’re in San Francisco. What can you say about the practice of mindfulness in Silicon Valley?

Purser: It’s huge. It really took off probably around 2010. Google became a sort of poster child for corporate mindfulness with the publication of Search Inside Yourself by Chade-Meng Tan, a Google engineer. Big conferences, like Wisdom 2.0, are held every year here in San Franscisco. It’s very popular in the Valley, which has always had this kind of spiritual, libertarian character to it. Steve Jobs had a background in Zen. But it’s selectively appropriated to optimize worker engagement. They’ll say it’s a form of “brain hacking.” In the 1960s, LSD was used for consciousness expansion, but now it’s used — via “microdosing” — to become more productive. Similarly, Zen was very anti-establishment and anti-materialistic, and now it’s used as a productivity enhancement tool for corporations.

By focusing only on individual-level stress reduction, these programs don’t take into account the systemic and structural problems in the workplace that are causing the epidemic of stress in the first place. In other words, there is no critical diagnosis of workplace stressors, which are long hours, work/family conflicts, economic insecurity, and lack of health insurance. Paulo Freire, author of Pedagogy of the Oppressed, called these “aspirin practices” because they promise to make the world a better place, but they really don’t change the root causes of stress that people are feeling.

Things like mindfulness seem very benign on the surface, so it’s almost incredulous to call them into question. But the harm is more at the socio-political level, because you’re basically letting corporations off the hook for responsibility of the social pollution they’re dumping on people. It’s not a form of brainwashing, or some conspiratorial thing, but what it does do is deflect attention away from collective ways of organizing to affect structural change.

Post: Do you see any signs of a movement that addresses your criticisms of this kind of individualistic mindfulness?

Purser: There are a lot of people on the fringes thinking about this besides me. I think we’re at a point where we have to come to terms with the idea that focusing on individual psychology and individual-based interventions are just not going to do it anymore. If you look at the ecological crisis, it’s a spiritual crisis. We’re dealing with suffering on such a systemic level that just retreating into our caves is problematic. I understand the need to cope, but the form of suffering that we’re dealing with is institutionalized and collective, not just at the individual level.

I think things can turn very suddenly and unexpectedly. If I were a practitioner of mindfulness in Australia right now, I think I may start considering other approaches. We have a hard time imagining other possibilities because we’ve been subject to this imagination machine of neoliberalism for so long that it’s hard for us to consider alternatives. We might want to turn to a more creative engagement with our own prophetic traditions — like the Judeo-Christian tradition — which account for social justice and oppression. A fundamental teaching in Buddhism is interdependence with all beings and with nature. I think that part of the equation hasn’t been given enough attention.

Purser’s book, McMindfulness, was published in 2019 by Repeater Books. Purser also recommends The Mindful Elite: Mobilizing from the Inside Out by Jaime Kucinskas.

Featured image by Repeater Books

Cartoons: Boardroom Buffoonery

Want even more laughs? Subscribe to the magazine for cartoons, art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

Bill King

October 14, 1944

Chon Day

October 4, 1952

Doris Matthews

June 7, 1952

Ross

March 15, 1952

Tom Henderson

March 8, 1952

Bill King

November 29, 1952

Chon Day

November 17, 1951

Want even more laughs? Subscribe to the magazine for cartoons, art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

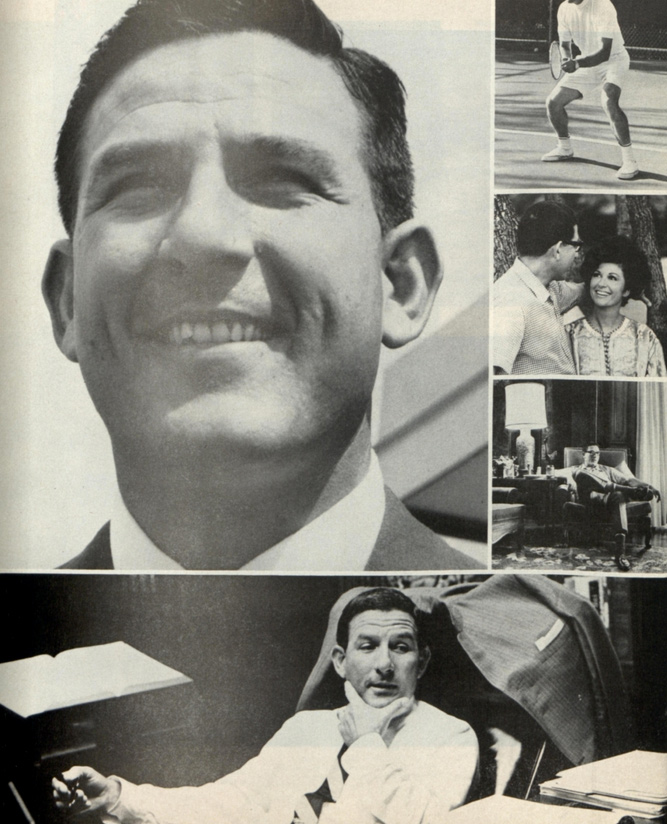

The Forgotten History of How 1960s Conglomerates Derailed the American Dream

Fifty years ago, you could hardly rent a car, buy a tennis racket, crank up your stereo speakers, or stock up on cans of corned beef hash without putting money into the pockets of James Ling. As the head of Ling-Temco-Vought, the Dallas businessman ran more than 11 corporate subsidiaries that made consumer electronics, packaged meat, and even developed aircraft used in the Vietnam War.

Ling’s conglomerate came into being alongside others, like ITT Corp. and Litton Industries, in the booming years of the 1960s. The low interest rates and simplified stock valuation of the era allowed these giants to take unprecedented hold of diverse industries, and in 1968 this magazine pronounced “It Is Theoretically Possible for the Entire United States to Become One Vast Conglomerate Presided Over by Mr. James L. Ling.” Just two years later, Ling was forced out of LTV, and the capitalist juggernauts of the decade met with an unraveling of the house of cards they had built in quick acquisitions and sketchy stock exchanges.

Ling was a postwar entrepreneur with a decidedly American life story. After his mother died from blood poisoning, Ling’s laborer father sent him to boarding school. He dropped out at age 14 and roamed the country doing odd jobs until he landed an opportunity as a journeyman electrician at an aircraft plant. Twenty-two-year-old Ling left for two years to serve in the Navy and furthered his skills as an electrician while maintaining equipment in the Philippines. Upon his return to Dallas, Ling was intent on transcending hourly wage work, so he sold his house and used the equity to start his own electrical contracting company.

The boldness and tendency for risk that characterized the ex-sailor’s foray into business would remain constant throughout Ling’s expansion. He hustled products and shuffled around finances to make it work for his small firm, garnering an industrial contract that he could barely fulfill. Within a few years, he was looking to go public in spite of an incredulous audience of Dallas business watchers. He hawked his stocks door-to-door and at a booth at the Texas State Fair and scrounged the money together with the help of some faithful investors.

By 1960, Ling-Temco was the 14th-largest industrial company in the country. Ling’s acquisitions over the coming decade dazzled investors as it appeared that he could make a company more profitable and efficient by swallowing it up. His business philosophy was based on the idea of synergy — or, in the ’60s, synergism — the concept that a conglomerate, as a whole, could be worth more than the sum of its parts. “What the sparsely educated Oklahoma poor boy discovered was that two plus two, properly added and managed with flair, can add up to seven or eight if you have enough brains and guts to handle the equation,” Don Schanche wrote of Ling in the Post.

While many American corporations formerly had taken part in vertical integration or horizontal integration (which stirred concern for monopoly), conglomeration in the postwar era — particularly in the ’60s — focused on diversification. Cornell University business historian Louis Hyman says, “It’s the first time that management is valorized as completely independent of the thing being managed. That’s how they justified these kinds of unrelated purchases.” The popularization of the MBA and the veneration of managerial science mystified the clever finances being wrought by conglomerate heads like Ling, who used debt and inflated stock valuation to grow their empires.

LTV’s stock price rose when they took on more subsidiaries, including Okonite, Wilson and Co., and Greatamerica Corp. Ling worked out complicated deals, then split the companies into smaller units, quickly selling the shares for more than the original value of the parent company. He discovered that revenue growth, even without profit growth, could make Ling and his shareholders a lot of money just by reorganizing balance sheets and continuing to acquire.

In Hyman’s recent book, Temp: How American Work, American Business, and the American Dream Became Temporary, he writes, “The real danger of conglomerates was not their power, but how their weakness perverted American corporations and helped to end the postwar prosperity.” Hyman believes the story of Ling’s — and nearly every other major American corporation’s — conglomeration years should be more widely known. Although the overall financial fallout was less acute than in 1929 or 2008, he says the lasting effects of conglomerates on the U.S. economy have been severe.

“My suspicion is that it led to the stagnation of the economy in the ’70s as people focused less on long-term investment and more on the fear of being conglomerated,” Hyman says. “It injected a measure of fear into American corporations.”

Ling’s business practices, under the guise of reflecting management genius, boiled down to a shell game in which longstanding, successful corporations were reorganized to the detriment of innovation and possible value creation. And he wasn’t alone: by the late ’60s, most of the 150 monthly mergers taking place were by conglomerates, which took up more than 90 percent of the Fortune 500. “Most American corporations that survived the 1960s figured out a way to handle conglomeration and deconglomeration,” Hyman says.

The force with which LTV grew led investors to believe it could never fail, and the Federal Trade Commission became concerned.

“The FTC already is worried enough about the growing conglomerate companies in the U.S. to have embarked on a long-term investigation,” Schanche wrote in the Post in 1968. “Ling has branded the probe ‘business McCarthyism’ and a witch hunt.”

The Justice Department filed an antitrust lawsuit against Ling after he acquired Jones and Laughlin Steel in 1968. Investors were troubled, especially since the suit coincided with other losses and a market downturn. The Times wrote, “LTV’s stock, which had traded for as much as $169 a share in 1967, plunged to a low of $4.25 the week Mr. Ling was ousted.” Ling was kicked out in 1970, and the once-gargantuan conglomerate, faced with low market prices, was forced into several divestures in the coming years.

Although the Justice Department’s investigations were timely, the reasoning for LTV’s downfall was in the market. Since Ling’s conglomerate was built on the premise that LTV’s high stock could be traded for the lower stock of his acquisitions, the Dallas man was in trouble (and in debt) when this scheme didn’t deliver.

LTV held on, through several bankruptcies, until 2000, but Ling found it impossible to continue his old ways in a new economy. He went into gas, oil, and real estate, bankrupting some companies and netting profit with others. His glory days were over, for good, and he had to part ways with his $3.2 million Dallas mansion.

In the shadow of the conglomeration years, economists rethought the merits of good management. Harvard economist Michael Porter’s research in the ’70s and ’80s shed doubts on the idea of synergy, and Jack Welch was celebrated for running General Electric more leanly in the ’80s and ’90s. Stock valuation became more detailed as well, focusing on measurable aspects of a company like free cash flow as opposed to accounting abstractions like profit and revenue.

That decade’s lessons of ravenous acquisition were learned perhaps most harshly by LTV and its investors, but their tale of unsustainable growth seems to be renewed with each bubble or boom. History doesn’t repeat itself, but injurious investment banking does.

Myriad opportunities for value and technological growth in the postwar years turned into decades of income stagnation and inequality, largely because of the high-stakes games played by conglomerates. “It’s easy to talk yourself into a deal that makes you and people you know lots of money, but actually harms the company,” Hyman says. In the case of James Ling, clever finances took precedence over production and innovation.

Contrary to the Post’s prediction fifty years ago, the entire United States did not become one vast conglomerate presided over by James Ling. Conversely, the Texan has been largely forgotten by anyone unfamiliar with the annals of American business. His philosophy of rushing for quick money over good economy, however, remains an enduring trope.