Your Health Checkup: The Unintended Health Consequences of a Pandemic

“Your Health Checkup” is our online column by Dr. Douglas Zipes, an internationally acclaimed cardiologist, professor, author, inventor, and authority on pacing and electrophysiology. Dr. Zipes is also a contributor to The Saturday Evening Post print magazine. Subscribe to receive thoughtful articles, new fiction, health and wellness advice, and gems from our archive.

Order Dr. Zipes’ new book, Bear’s Promise, and check out his website www.dougzipes.us.

COVID-19 has disrupted practically every aspect of life on earth as we know it. The rate of infection and mortality from this coronavirus is appalling, especially in the U.S., with numbers worsening as we head into the winter flu season. There are more than 8 million cases and 220,000 deaths, perhaps reaching 400,000 by year’s end. Many hospital ICU beds are full.

Scientists have told us what to do: wear a mask, keep your distance, avoid large gatherings, wash hands, and stay outdoors as much as possible when socializing.

But so many people battle these simple measures. It reminds me of initial resistance to wearing seatbelts in cars or helmets on motorcycles. The spurious objection that these requests encroach on civil liberties is absurd. Licenses are required to drive, own a firearm, hunt, fish, and do a myriad of other things. Why are these requirements not an intrusion on civil liberties, but wearing a mask is?

In addition to the obvious impact on our daily activities, COVID-19 has exerted unintended consequences that can pose long term risks to our health. Americans have scaled back multiple health care initiatives to an alarming degree.

Vaccinations have plummeted, even as we enter the flu season. Critical childhood vaccinations for hepatitis, measles, whooping cough and other diseases have declined significantly. Measles was already increasing before this year, possibly due to the growing strength of the anti-vaccination movement. Fewer children vaccinated because of coronavirus fears could worsen the trend. Childhood immunizations fell about 60 percent in mid-April in 2020 compared to 2019, ranging from 75 percent for meningitis and HPV vaccines to 33 percent for others like diphtheria, tetanus and pertussis.

Screening colonoscopies are almost nonexistent as are other preventive health care procedures like prostate checkups, mammograms, Pap smears and glaucoma evaluations. Routine doctor office visits have declined greatly. The potential consequences are an increase in vision loss; colon, breast, and prostate cancers; communicable diseases like measles and mumps; and reduced screening for illnesses like hypertension, diabetes, and coronary disease.

Equally or even more alarming is a decline in hospital admissions for acute illnesses like heart attacks. For example, a multicenter survey in Italy found almost a 50 percent reduction in admissions for acute heart attacks compared with the equivalent week in 2019. The decreases were associated with parallel increases in mortality and complication rates. Similar trends have been noted in England, the U.S., and other countries as well.

COVID-19 has frightened patients from seeking medical help for life threatening problems, as well as from preventive measures. We cannot let the trend continue. As we’ve heard in countless newscasts from scientists such as Dr. Anthony Fauci, the nation’s leading infectious disease expert, we as a nation must come together to fight this pandemic as a unified population.

Listen to the scientific experts, not the carnival barkers. Do as these recognized experts advise. Wear your mask and wash your hands! Get the COVID vaccination when it becomes available. Waiting for “natural herd immunity” to occur is dangerous and could result in over 2 million deaths.

And don’t forget the usual, but important, preventive measures, and seek medical help as you would have before the pandemic struck. Your life may depend on it.

Featured image: K.Yas / Shutterstock

Why You Should Get to Know the Folks Next Door

My book In the Neighborhood, published 10 years ago this spring, asked how Americans live as neighbors — and what we lose when the people next door are strangers. These questions are just as timely today. Not only is the country dealing with the COVID-19 pandemic, it is also facing a political crisis. And on top of these global and national issues, there are often painful personal matters, such as the sort of health crisis that my own family recently experienced. In each instance, neighborhoods have a critical role to play in easing adversity and averting disaster.

The inspiration to write my book came from the murder-suicide of a couple — both physicians — who lived on my suburban street in Rochester, New York. One evening the husband came home and shot and killed his wife, and then himself; their children, a boy, 11, and a girl, 12, ran screaming into the night.

What struck me — besides the tragedy — was how little it seemed to affect the neighbors. A family who had lived on our street for seven years had vanished, and yet the impact on the neighborhood seemed slight. No one, I learned, had known the family well. Few of my neighbors, I later learned, knew each other more than casually; many didn’t know even the names of those a door or two away.

Interestingly, many of the happy connections between neighbors occurred in response to natural disasters.

Do I live in a neighborhood, I asked myself, or just in a house on a street surrounded by people whose lives are entirely separate? Why, I wondered, in this age of instant and universal communication — when we can create community anywhere — do we often not know the people who live next door?

To see if I could connect with my neighbors beyond a superficial level, I asked them if I could sleep over at their houses and write about their lives on our street from inside their own homes. Somewhat to my surprise, about half the neighbors I approached said yes.

Getting to know my neighbors in this way enlivened the experience of living there. It helped me forge connections that enriched my life and made it easier for the people on my street to look out for each other.

After I told my story in the book, I heard from people all over the world about how much they missed close neighborhood ties. They also told of more recent times when they’d managed to connect with their neighbors, and how gratifying those experiences had been.

Interestingly, many of the happy connections between neighbors occurred in response to natural disasters. On the West Coast, readers recounted earthquakes and fires; in the South, hurricanes and floods; in the North, massive snowstorms. “When the power went out,” a Florida man wrote me of his neighborhood during Hurricane Andrew, “we began to cook our meals in the street. We enjoyed getting to know each other and learning each other’s stories. After a few days the power came back and we all went back inside. It’s funny, but I find myself looking forward to the next hurricane so we can catch up.”

Today, we’re all living through an unfamiliar kind of natural disaster — the coronavirus pandemic — and I see that neighbors are connecting once again. We’ve read and heard a lot of these stories, so I’ll share just one from my own family.

Just after New Year’s 2020, my 4-year-old granddaughter, my daughter’s child, was diagnosed with a rare form of childhood cancer. Suddenly, her life and the lives of her parents and 2-year-old sister were upended. What had been the happy, busy life of a growing family was now beset by fear, anger, uncertainty, trips at all hours to the hospital, increased medical bills, and two parents trying to work remotely from home.

We’re 11 times more likely to report high levels of confidence in our neighbors than in the federal government, and 5 times more than in our city councils.

My daughter’s family lives in a suburb of Washington, D.C., where the response to their 4-year-old’s health crisis was … nothing. This was not because the neighbors were unkind; it was mostly because my daughter and her husband, after living in their home for nearly four years, knew few, if any, of their neighbors well.

But the COVID-19 pandemic came just three months after my granddaughter’s diagnosis. Suddenly everyone in the neighborhood was living with fear and uncertainty, working remotely from home, and struggling with unknowns including reduced income. On a neighborhood listserv, someone offered to buy groceries and other supplies for anyone especially vulnerable to the virus.

My daughter responded:

Hi neighbors—

Some of you have offered so generously to pick up groceries for those of us who are immunosuppressed. I’m pregnant and one of my children has cancer. If anyone happens to be at a store this week selling toilet paper, tissues, or paper towels, please pick up some extra for us! Happy to pay, of course.

Thank you!

Valerie

The response was swift and strong:

My daughter will deliver items shortly (I’ll wear gloves when I put the items in the bag, so nothing will have been touched by anyone in the house).

Amy

We dropped off some tissue boxes a few mins ago.

Allison & Michael

I have a couple smaller boxes of tissues I’d be happy to drop off to you. Oh and I can give you a container of Clorox wipes too.

Betsy

I just dropped off paper towels and tissues at your front door.

Fran

And that was only the beginning. For weeks, my daughter has been finding bags of groceries and paper goods on her doorstep; in most cases, the neighbors decline payment. “Don’t be silly,” one wrote. “There will surely come a time when I need a favor from a neighbor.”

Today, my granddaughter’s treatments continue and her prognosis is good. Her family’s life is still upended, but now at least they are aided and comforted to know they live among people who know and care about them. Once again, it took a terrible event to bring neighbors together.

Can we find ways to connect with each other without a disaster?

As Americans, we have an independent streak; our impulse for freedom and self-reliance often comes more naturally than the desire for community. Social trends also work against connections. Two-career couples mean fewer people are at home or have the leisure time to interact with neighbors. Larger suburban homes — and the lots they sit on — increase physical distance. Ever-increasing hours of screen time leave us less time to socialize. And the persistent fear we call “stranger danger” steers us away from meeting others — even those who live nearby.

I’m afraid it would be naive to think that — in the absence of a new disaster — we will all just reach out to our neighbors because it’s a nice thing to do.

So, let me offer a different incentive.

Pandemic aside, this country is experiencing a crisis: Politically, we have torn ourselves in half. Whichever side you’re on, half the country thinks you’re not only wrong, but insane.

It’s a crisis that poses a threat greater than any hurricane, fire, earthquake, or pandemic. Left unchecked, I fear it can rip us in two and in the process — regardless of which side prevails — destroy the very protections we rely on for our freedom.

What is the answer? History suggests if we want to begin to repair the social fabric, a good place to start is our own neighborhoods.

Like the meetinghouses and common greens of earlier times, neighborhoods long have been the building blocks of a healthy civil society. Today, they are a place that allows us to get to know, regularly and intimately, people who may think differently than we do. With effort, we can come to know our neighbors beyond a superficial level, to know their challenges and the fullness of their lives. Once we do that, it becomes hard to mark them only with political labels.

For example, there’s a couple that lives near me. Over the years, I’ve seen them work long hours to build their own businesses — he in sales and she in consulting. I’ve come to know the two children they adopted, and for whom they’ve made a loving home. I watched as they remodeled a spare room for her mom to live in when she could no longer live alone. So I’m not inclined to dismiss my neighbors — and certainly not to think them evil or insane — merely because they’ve posted a lawn sign supporting a national candidate with whom I disagree.

“In this age of bitter partisanship and social division,” writes Ryan Streeter, resident scholar at the American Enterprise Institute, “unity and social healing are not only possible but happening every day when we work with and rely on those who are closest to us.”

In the 2019 Survey on Community and Society, Streeter and colleagues found that most Americans get a stronger sense of community from those they’re close to, including neighbors, than from “their ethnicity or political ideology.” Moreover, they found we’re 11 times more likely to report high levels of confidence in our neighbors than in the federal government, and 5 times more than in our city councils. Seventy-three percent of us say our neighbors can be counted on to do the right thing.

So let’s not wait for the next natural or even man-made disaster to reach out to our neighbors. We have a strong enough motive: healing the bitter partisanship that infects our country.

How to get started? I think it’s just one neighbor at a time. You don’t even have to sleep over. All it takes is making a phone call, sending an email, or ringing a bell.

Peter Lovenheim is a journalist and author of six books. His 2011 book, In the Neighborhood: The Search for Community on an American Street, One Sleepover at a Time, won the First Annual Zócalo Public Square Book Prize. He is Washington correspondent for the Rochester Beacon.

Originally appeared at Zócalo Public Square

This article is featured in the September/October 2020 issue of The Saturday Evening Post. Subscribe to the magazine for more art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

Featured image: Shutterstock

What’s Happening to Halloween?

America has to face a frightening fact this October: we are still in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic. Even with states reopening and calls from certain quarters to get back to business as usual, coronavirus cases are on the rise in 27 states as of this writing. With a proper vaccine still a fair distance from the horizon, many are wondering what to do about that most social of holidays, Halloween. The creepy catch is that there’s no single standard or strategy across the nation, so here’s a snapshot of how different communities are handling various events in the hopes that the outcome isn’t too scary.

The Louisville Jack O’Lantern Spectacular: The Post called this the “Best Halloween Event in the Midwest” in 2018. This year, The Jack O’Lantern Spectacular will still boast over 5,000 intricately carved and lighted pumpkins, but the event will be a drive-thru affair. Organizers decided that it was a solid way to hold the event but still maintain social distancing. The Spectacular, which benefits the Louisville Parks Foundation and requires tickets, runs now through November 1.

Haunted Houses: Local haunted house attractions are a mixed bag. Some have opted to close, and some, like Hanna Haunted Acres, which the Post visited in 2019, will remain open. HHA, considered one of the best haunted house events in the country, lists the series of precautions that they’re taking on the front page of their website. Face masks are required, capacity will be limited, and distancing will be maintained. Contact-free temperature checks are required to enter. The staff has upgraded cleaning procedures and made more hand-sanitizing stations available for patrons. The Hanna website also contains more COVID-19 information for guests, including safety reminders and symptom lists (that could guide you to remain home). Haunted attraction site TheScareFactor.com is maintaining a running list of which regular attractions are open or closed in all 50 states, plus Washington D.C. and Puerto Rico. The state with the most closings is California, with 37, though 32 are open and 90 are unconfirmed; the state with the most remaining open is Ohio, with 72, which is offset by 34 closed and 25 presently unknown.

It’s Free to See the Full Moon (Both of Them): 2020 has been legitimately spooky, so spooky in fact that October this year gets two full moons. By a twin quirk of astronomy and the calendar, the first three days of October have a full moon, and it will be full again on Halloween (which is rare; the last full moon on Halloween that was visible in North America was in 1944). It should be an extremely bright moon as well. Granted, you might not be able to build a whole event out of seeing the full moon, but it’s easy (and free) to do while maintaining socially distancing.

Staying Safe the CDC Way: The Centers for Disease Control added a section to the “Your Health” area of their website that’s all about staying safe throughout the holidays. The section comes with a lengthy introduction about precautions to take in the event that you host or attend any kind of holiday gathering. In the Halloween segment, the CDC lists activities and whether they can be considered lower, moderate, or higher risk. Many traditional activities like treat-or-treating, trunk-or-treat events, indoor haunted houses, and indoor parties fall into the higher-risk area.

Likewise, CNN Health also published a list of 31 activity suggestions that people can do safely. These ideas run from the extremely modern (celebrating with Animal Crossing) to the tried-and-true (Scary Movie Night).

State by State, City by City: Every community, city, and state is likely to have their own rules, which you should be able to find online. Cities like Los Angeles will be shutting down larger gatherings and have forbidden big events like carnivals and haunted houses from operating at all. The famous Greenwich Village Halloween Parade in New York has been cancelled, as have big events in Salem, Massachusetts. Here’s a list of some of the more significant cities with cancellations or big changes.

One example of state rules can be found in the Illinois Department of Public Health’s response to Halloween activities. The IDPH encouraged people to stay at home, but also acknowledged that people will go out anyway and therefore issued guidelines. A statement from IDPH Director Dr. Ngozi Ezike in The Chicago Tribune emphasized some familiar points: “Remember, we know what our best tools are: wearing our masks, keeping our distance, limiting event sizes, washing your hands, and looking out for public health and each other.” Illinois is also one of several states that is prohibiting indoor haunted houses at the moment, though outdoor versions may still occur under restrictions. Consult the guidelines for your community to see what is and isn’t allowed this year.

The Choice is Yours: The decision about what to do (if anything) for Halloween is up to each individual (or each family). The best practices are obviously to be cautious and thoughtful. Costume masks don’t work like personal protection masks, for example, and indoor gatherings offer some of the highest risks. There are clearly a number of ways to have a good time, even if we have to modify the expectations set by previous holidays. As long as you practice social distancing, make smart choices, and avoid babysitting in Haddonfield, Illinois, you can still have a Happy Halloween.

Featured image: (From the 2018 Louisville Jack O’ Lantern Spectacular; photo by Becky Brownfield)

5 Times That Disease Unexpectedly Changed American History

Very few people foresaw the full impact of COVID-19 in America. And with the president’s recent announcement that he himself has been infected, there is much uncertainty about the repercussions his illness will have on his party, the government, the stock market, and the electorate.

But this is the nature of infectious diseases: the full impact of their arrival, departure, and consequences are rarely foreseen.

This has been seen repeatedly throughout history. During the Civil War, for example, America expected there’d be casualties from soldiers dying in the field of combat. What they didn’t expect was that most would die far from the fighting, as soldiers crowded in camps spread cholera, smallpox, and other infectious disease. More than half of the war dead were victims of disease.

Here are five times major illnesses had unexpected outcomes.

Malaria Fueled the American Slave Trade

Among the earliest European settlers to America were planters who arrived in South Carolina to grow rice. They soon discovered the marshy lowlands where they planted were infested malaria-bearing Anopheles mosquitoes. The disease, which reproduces in red blood cells, proved fatal for white workers in the fields, and planters had trouble maintaining their crops. But they discovered that recently enslaved Africans had a degree of immunity to malaria because of the genetic condition sickle-cell anemia. Rice became a successful crop, followed by cotton, both tended by slaves.

Planters didn’t know what gave the enslaved Africans their ability to endure malaria. They assumed it was because they were genetically hardier. This was far from true; half of all Black children born into American slavery died before reaching the age of five.

Disease Was a Sign of American Success

At the time of the Revolution, Americans enjoyed far better health than their contemporaries in Europe. The average height — a good indication of the state of health — was 68.1 inches, just one inch lower than the average height today (the average European measured 65.76 inches). Roughly 60 percent of children raised in the country survived to age 60. (page 123, “Deadly Truth”)

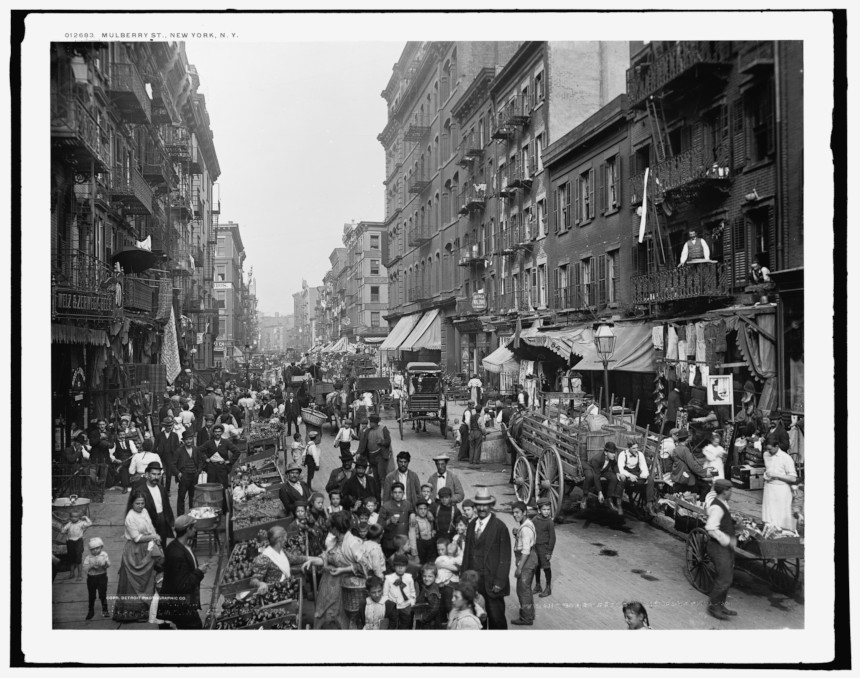

According to The Deadly Truth: A History of Disease in America by Gerald N. Grob, almost all Americans of the early 1800s resided in the country, leading exceptionally healthy lives. They lived far apart, with little exposure to strangers bearing illnesses; they had healthy diets and a clean environment.

But the population began shifting toward the cities, according to Grob. Between 1800 and 1850, for instance, the population of Philadelphia increased 500 percent, consisting mostly of Americans leaving the country for the city. They were attracted by the commercial possibilities and the opportunity to enrich themselves beyond anything they could realize on a farm.

They came despite the already high risk of contracting a fatal disease in the city. Between 1721 and 1792, Boston was hit by seven epidemics. An outbreak of yellow fever in 1793 killed 1 in 10 Philadelphians.

Urban crowding made disease transmission easier. Water supplies became contaminated. Immigrants, sailors, and visitors brought fresh injections of diseases. Cholera and yellow fever spread rapidly, and cities didn’t have the resources to care for the sick. In big cities like New York and Boston, only 16 percent of children reached their 60th birthday. By 1830, the average male height in America had fallen to under 67 inches.

A Mysterious Illness in Midwestern Livestock Began Emptying Towns

In the 1800s, settlers in the Ohio River Valley noticed livestock sometimes developed a trembling in their legs that soon led to collapse and death. Shortly afterward, their owners showed the same signs, as well as abdominal pains and vomiting. Farmers called it “milk sickness” and believed it was caused by an infectious agent.

The disease proved highly fatal in pioneer settlements, sometimes claiming up to half the residents. Areas of Kentucky and Illinois were especially hard hit. One of its victims was Abraham Lincoln’s mother.

The disease abated as the land became settled and animals began grazing in pasture land instead of the wilderness. It wasn’t until 1923 that Dr. Anna Pierce Hobbs Bixby learned from a Shawnee woman the cause of the sickness. Sheep and cattle were eating snake root, a member of the daisy family, which contains tremetol, a poison so strong it can kill animals and lethally poison its meat and milk. But in the days before it was discovered, the flow of settlers stayed away from areas where milk sickness was reported.

Another Disease Brought Prosperity to Colorado

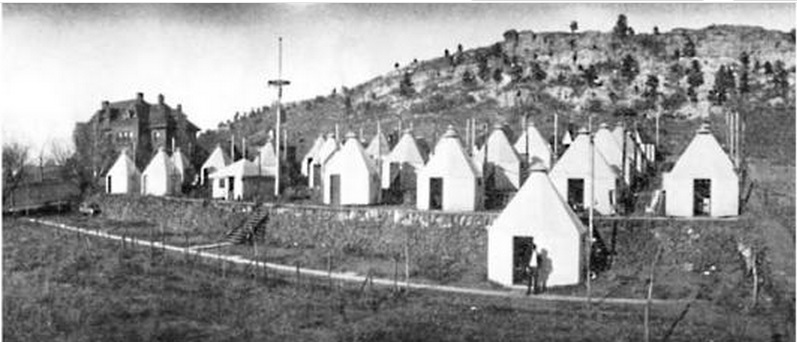

America’s number-one killer in the 1800s was tuberculosis. Doctors didn’t understand its cause or course, but it seemed to be connected with damp, polluted air. So doctors advised TB patients to move to higher altitudes, where the air was dry and conditions sunny. The recommendation was partly useful. The decreased oxygen levels at high altitudes slowed the growth of the mycobacterium-causing organism. And the sunlight and fresh air was always good for patients.

There were plenty of high altitudes and sunny weather in Colorado. Prior to the 1860s, it had been just another empty stretch of the western wilderness, sparsely peopled by miners and prospectors. But soon a growing number of sanitariums opened in Denver, Boulder, and Colorado Springs, and began to fill with tubercular patients. In time, they made up a third of the state’s population.

Cities grew up around the sanitariums, which attracted caregivers, support staff, and visitors to the patients. And TB patients often helped the town develop, bequeathing money to build streets and schools. In Denver alone, the population rose from 4,700 in 1870 to 106,000 in 1890.

Cleaning Up the Cities had Unintended and Fatal Consequences

Americans were shocked when a polio epidemic struck New England in 1916. For years, the incidence of the viral infections had declined almost to insignificance. Now, suddenly, 9,000 people had contracted the virus and 2,400 died — a fatality rate of 27 percent. The reason for the resurgence was completely unexpected.

Polio is caused by one of four viral strains. In the days before the Salk vaccine, most cases of polio ran their course in a day or two without serious complications. Only one case in 100 produced clinical symptoms, and even fewer caused paralysis. Most people experienced it as a low fever, headache, sore throat, and discomfort. But if the virus attacked the spine or the muscles controlling breathing, the consequences were quick and often fatal.

Up to the 1900s, most children in cities lived in crowded conditions and had been exposed to one of the strains at an early age. Or they gained immunity from maternal antibodies passed on to them as infants. Either way, most children growing up the congested cities were immune.

But as housing became less crowded and cleaner, there were fewer opportunities for exposure. A generation matured with little or no exposure and immunity. Polio swept through these communities quickly, striking down defenseless Americans. Franklin D. Roosevelt is a good illustration. He had grown up in wealth and comfort, and so had no immunity when the virus hit him in 1921 at the age of 39.

Featured image: Ward K, Armory Square Hospital, Washington, D.C., 1864 (Library of Congress)

The Streaming Wars: And The Child Shall Lead Them

The Post has been covering the Streaming Wars for some time now. In the past several months, a number of new developments have taken hold. These include services embracing a new kind of Video-On-Demand (VOD) model, some new service launches, and several layers of content reshuffling. HBO Max, Peacock, and Quibi all launched with various problems, while CBS All Access seems headed for a merger with a larger platform. And then there’s The Mandalorian, which barnstormed social media with breakout character “The Child” (aka “Baby Yoda”) on its way to a jaw-dropping 15 Emmy nominations. But what about stalwarts like Netflix? And how does the Age of COVID-19 change the shape of what’s to come? Here’s your war report.

Lockdown on Demand: When theaters closed across the country with the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, studios scrambled to change dates and look at alternative delivery formats. One victory was found at the drive-in; the built-in social distancing that comes with watching a film from your car allowed some new releases to filter out, some old favorites to come roaring back, and for some small films to generate (for them) big numbers. One of the first movies that was slated for a big theatrical release, but shifted to a VOD delivery, was Trolls World Tour. The sequel to the hit 2016 animated musical became available for digital rental on April 10 (which was the same day that it debuted in a limited number of theaters), but at a steeper rental price point that would be more akin to taking a family of four to the movies. The film made a startling $40 million off of rentals in its opening weekend. IndieWire estimated in August that it’s made around $150 million in rentals through the life of its release. Other studios have followed suit with select releases. Bill & Ted Face the Music from United Artists bowed in select theaters and for a $19.99 rental across a number of services. In just four days, it was Fandango’s top title for all of August.

The trailer for Mulan. (Uploaded to YouTube by Walt Disney Studios)

However, it looks like Disney+ is in line to have lightning strike twice. The first major mouse move was to bring the filmed version of Hamilton to the service months before it was scheduled to arrive in theaters. The July 3 release spurred a quarter of a million new Disney+ subscriptions that weekend, and Variety reported that roughly 37 percent of all the app’s subscribers watched the musical in its first month. The second big release shuffled to the platform was the live-action remake of Mulan, which debuted September 4. Early indications are that Mulan’s performance may easily surpass Hamilton’s, with one major catch; Hamilton was simply an addition to the platform, whereas you presently have to pay $29.99 to get Mulan. With Disney+ passing 60 million subscribers in August, it would only take 8 percent of subscribers ordering Mulan for the film to clear nearly $150 million. That would be a major victory for the company, and it would make it much more feasible for other delayed blockbusters (like Black Widow) to make a profitable simultaneous home and theater debut.

New Launch Woes: Even as the traditional HBO channel is garnering attention and praise for its new series, Lovecraft Country, the rollout of the new HBO/AT&T/WarnerMedia app HBO Max has been something of a headache. When HBO Max landed in May, it wasn’t available through Roku or Amazon/Fire devices . . . and it still isn’t; the problem is that those two options represent approximately 70 percent of the streaming player market in the U.S., and they’re locked in a dispute with HBO Max over fees. Additionally, roughly 20 million people who subscribed to HBO, and who would have gotten HBO Max rolled in with their sub, simply didn’t activate the service when it started, meaning that HBO Max only had about 4 million official users by the end of June. There was also confusion when HBO’s other apps (HBO Go and HBO Now) went away and were replaced with, simply, an app called HBO. That app offers the programming that Now did, including current series, but doesn’t have access to the Max exclusive series or the wider content libraries (like the Criterion Collection) that were rolled into Max. Confusing content deals haven’t helped; while the Harry Potter franchise and various DC Comics-based films were heavily advertised for the launch, pre-existing deals with other services meant that many of the DC movies vanished in the first week, and the app lost the Potter films in August. The struggling DC Universe app will have its content rolled into HBO Max, but questions linger about whether its extremely popular digital DC Comics library will make the transition or go elsewhere.

Depature is one of many originals headed to Peacock. (Uploaded to YouTube by Peacock)

The NBCUniversal app Peacock kicked off for Xfinity users in April; it landed on other platforms in July and worked up to 10 million viewers by the end of that month. It has a free tier that accesses 15,000 hours of content; the pay levels unlock about 5,000 more. With NBC Sports deals for soccer and content with third-party providers like ViacomCBS and Paramount Pictures on the way, Peacock is putting together a big library, and is looking to Parks and Recreation (arriving in October) and The Office (arriving in January 2021) to boost subs. However, it has one big problem in common with HBO Max: you won’t find it on Roku or Amazon. Peacock also had some of its big launch-day draws, like the Fast & Furious franchise, The Matrix, and Shrek already vanish. New content has taken a hit due to the COVID-19 shutdowns. In the face of these issues, which users have complained about readily on social media, there has also been praise for a “channels” feature that runs clips and content around different themes. The Today All Day channel gathers The Today Show segments, and other channels are devoted to Saturday Night Live and other themes.

Quibi is a mobile streaming platform that launched with free trials in April with an eye toward shorter programming. The 10-minute episodes are referred to as “quick bites” (a phrase that was truncated into the service’s name). While a number of high-profile companies invested in the service and stars like Anna Kendrick and Kiefer Sutherland dot the programming, the download numbers for the app crashed after the first month of operation. The company cut staff in June amid reports that its 2 million subscribers fell well under a proposed 7.4 million user goal. The Verge reported in July that the conversion rate from free initial user to paid subscriber was a poor 8 percent.

A Viacom Mind-Meld: CBS All Access has put together a base of around four million subscribers. The service has bet big on Star Trek so far, with three active series (Discovery, Picard, and Lower Decks) and two coming (Strange New Worlds and Section 3). One much anticipated show is the upcoming adaptation of Stephen King’s The Stand, which launches in December. Like Apple TV+, CBS All Access has been actively gathering other content; parent company ViacomCBS looks to merge All Access with programming from its other brands (MTV, BET, Nickelodeon, Comedy Central, etc.) with the notion of competing with the bigger services.

Update: Early on Tuesday morning, September 15, one day after this story originally posted, ViacomCBS announced that CBS All Access will be rebranded in early 2021. Under the new name Paramount+, the service will roll in CBS All Access programming with the other brand verticals mentioned above for a larger, more competitive service.

The Morning Show has been a major success for Apple TV+. (Uploaded to YouTube by Apple TV)

Apple in the Middle: Apple TV+ is doing all right. The streamer already renewed most of its original drama and comedy series and the service claimed 18 Emmy nominations, including nods for The Morning Show, Defending Jacob, and Beastie Boys Story. While Apple had intended for the service to focus on original content, it went into acquisition mode in the middle of the year after COVID-19 shut down original productions. The app actively bought films like Tom Hanks’s Greyhound and Will Smith’s upcoming Emancipation to bolster content offerings. Apple also has a robust development slate for series and films spread across the next few years; it has the potential to develop into destination viewing for unique programming over the long term.

The Big Kids on the Block: Netflix, Amazon’s Prime Video, and Hulu remain the big dogs in the yard, with Disney+ joining the pack. Prime Video is available to Amazon Prime’s 150 million subscribers around the world, though about 26 million actively use it. Hulu has 35 million paid, with over 3 million of those opting for Hulu+Live TV to replace cable service. Disney+ passed 60 million in their first year, stomping their initial estimate that it would take until 2024 to get 60 to 90 million subscribers. Netflix remains the numbers champ, with 193 million paid users.

Each of those services continues to offer strong performances in various areas. Prime’s The Boys has been a breakout critical and commercial hit, and anticipation is high for the forthcoming Lord of the Rings series. Hulu had a big quarantine hit with original film Palm Springs, a strong development slate, and offers returning water-cooler programs like The Handmaid’s Tale. Netflix is, of course, Netflix, and wields enormous programming influence; the primary viewer complaint about the service is the impression that many series don’t get past three “seasons” or that they appear very quick to cancel shows that might grow with more time. Nevertheless, Netflix cuts a dominant figure, especially with the success of films like Extraction, break-out series like The Witcher, and their ongoing live-comedy specials.

The trailer for The Mandalorian Season One. (Uploaded to YouTube by Star Wars)

As for Disney+, its first year has seen a subscription base that exceeded expectations, 19 Emmy nominations, and a legitimate pop culture phenomenon in the form of The Child, the inhumanly cute “Baby Yoda” that co-stars in The Mandalorian. That Star Wars spin-off accounted for 15 nominations, including an unexpected nod for Best Drama. The service also had the good fortune to have The Mandalorian season two filming completed before the pandemic; editing and effects continued remotely, which will allow the next set of episodes to debut in October as scheduled. Additionally, the much-anticipated Marvel Cinematic Universe installment The Falcon and The Winter Soldier is still expected to debut this fall after an initial delay from the COVID shutdown. All of that is, of course, on top of one of the most powerful libraries in entertainment, which includes the Marvel and Star Wars brands, the Pixar films, Disney animated classics, and National Geographic, in addition to acquisitions like Beyoncé’s video album Black is King.

| Service Name | Price Per Month | Program Highlights |

|---|---|---|

| Amazon Prime Video | $8.99 standalone; $12.99 w/full Prime | The Boys, The Expanse, The Marvelous Mrs. Maisel |

| AppleTV+ | $4.99 | The Morning Show, For All Mankind, Servant |

| CBS All Access | $5.99 | Star Trek: Discovery, Star Trek: Picard, ST: Lower Decks |

| Disney+ | $7; $12.99 bundled with basic Hulu & ESPN+ | The Mandalorian; The Imagineereing Story |

| HBO Max | $14.99; $143.88 for 1-year deal available | Raised by Wolves; Doom Patrol |

| Hulu | $5.99 basic; $54.99 +Live TV; ad-free tiers also available | The Handmaid’s Tale; Castle Rock; Shrill, Letterkenny |

| Netflix | $8.99 basic; $12.99 standard; $15.99 Premium | The Umbrella Acadmey; Cobra Kai; Lucifer; Away |

The streaming landscape has become a crowded, constantly shifting place. It’s possible for multiple large outlets to co-exist; even with the pervasiveness of Netflix, it’s obvious that several other companies have very healthy options. The big question is how many of these services will thrive in the long term. At some point, every household will hit saturation on the number of services that they actually use, or can afford. Until then, the various entrants will continue to jockey for position in a race that is much more a marathon than a sprint.

Featured image: Ivan Marc / Shutterstock

The Upside of Hypochondria

I have lots of friends who work in the medical field and are exhausted by the extra burden they’re shouldering in these virulent times. Most of the things I do as a pastor are now discouraged — meeting people face to face, visiting hospitals and nursing homes, tending to the sick and shut-in. Electronic interaction is helpful, but it lacks the spiritual and emotional quality of holding someone’s hand. Still, it’s better than nothing, and I’ve found other ways to pass the time, chief among them wondering if I have the coronavirus and how soon I’ll die.

Being a hypochondriac, I have something of a talent for hysteria and regularly (several times a day) remind my wife how tenuous is my grasp on life. Every tickle in the throat, every bead of sweat, every pant for breath is a portent of my agonizing and imminent end. I’ve been a hypochondriac since early childhood, when I discovered the best way to get my parents’ attention was to feign death. I missed an entire month of fifth grade after convincing them I had leprosy, which I had learned about in Sunday school. It turns out that weakness, vision problems, and peripheral numbness are easy to fake. After the first week of acting, I convinced myself I actually had leprosy and sat around for three weeks waiting for my nose to rot off.

I have something of a talent for hysteria and regularly remind my wife how tenuous is my grasp on life.

It’s odd that the best month of my childhood was when I had leprosy. Mr. Evanoff, my teacher, had my classmates make me get-well cards. Jerry Sipes, who hadn’t liked me since I’d reported him to the teacher for peeing on the bathroom floor, wrote in his card that he hoped I died, and Patty Worely, whose dad was a minister, urged me to accept the Lord so I wouldn’t go to hell. She mentioned she was praying for me every day, which I’m certain ended up saving me from the leprosy I quite possibly had. My Grandma Norma sent me a letter with $10 in it, and my dad bought me a box of stale Hostess cupcakes from the Hostess Bakery Outlet in Terre Haute. Twelve cupcakes all to myself, which I think gave me diabetes, so now I’m just waiting for my legs to rot off.

The good thing about hypochondria is its tendency to fill all your waking hours, making other hobbies unnecessary. There isn’t a day that passes that I don’t wonder about the ailments my body is harboring — consumption, dropsy, palsy, and swine flu. I’ve had them all, probably. I fall asleep each night, praying I’ll make it to morning but doubting I will. Unable to sleep (a sure indication of hyperthyroidism), I climb out of bed, walk down the hall to my office, and jot down some notes to my wife regarding my funeral. There are a few people I don’t care for (Jerry Sipes, for instance), who I know don’t care for me, and I don’t want them showing up pretending they liked me. We hypochondriacs can’t stand hypocrisy.

I’ve given years of thought to my funeral. Who’ll give the eulogy? Which songs will be sung? What will they eat at my funeral dinner? What clothes will I wear? Do I go with a suit, wanting to leave a favorable last impression, or should I wear blue jeans and a flannel shirt, reminding my family and friends I was a man of the people? Now with the coronavirus and social distancing, no one will likely attend my funeral, and there goes my chance to watch people’s faces when they see me in the casket and realize I really was sick all these years.

Philip Gulley is a Quaker pastor and author of 22 books, including the Harmony and Hope series featuring Sam Gardner.

This article is featured in the September/October 2020 issue of The Saturday Evening Post. Subscribe to the magazine for more art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

Featured image: Shutterstock

In Praise of the Slow Movement

It was a long time coming, but the Slow movement has lately picked up momentum in America. Suddenly — too quickly? — it’s a thing.

The coronavirus pandemic is, of course, the explanation. It accelerated a trend that has been simmering for years — the desire to ease back a bit and live more fully in the moment, to seek greater balance, to satisfy the impulse to get in touch with one’s inner tortoise. In other words, to … slow … down.

This year much of the world was jolted into an involuntary disruption of familiar rhythms. It has been a particularly harsh reality in America, where we worship nonstop speed. Fast meals, fast deals, fast cars, fast internet, fast divorces. Don’t dawdle! Race to the finish line.

But ever since the virus crashed our hurry-up lives, we’ve had little choice but to adapt — to be more appreciative of our blessings, more attuned to nature, and, to an extent, slower.

A confession: It was just several months ago that I first stumbled across the Slow movement, even though it’s been around for more than 30 years. It emerged out of what’s popularly called Slow Food, which got its start in Italy. Slow Food gave rise, over time, to Slow Cities, Slow Journalism, Slow Fashion, Slow Sex, Slow Medicine, and Slow Politics. All these Slows emphasize slipping into the natural flow of life, resisting a reflexive break-neck gallop. (Note: You want a more details on Slow Sex? This is not the place, but I’d suggest that the topic is well worth researching. Lots of fascinating material. No need to rush through it.)

You see what I just did there? My detour into sex had the effect of momentarily diverting your attention from the main event — which was intentional. Because one of the tenets of the Slow movement is that meandering yields its own sweet rewards.

I like Slow very much. You’ll never catch me being all show-offy fast. “Pace yourself, Cable. Let’s not be a gazelle,” I hear myself saying daily. Furthermore, I’m not one of those breast-beating multitaskers. More of a minimally effective unitasker.

To be clear, the Slow movement does not ask that we decelerate to a crawl. It only demands that we marinate more completely in our hour-to-hour activities, enriching our lives by savoring what most matters and not trying to impress ourselves (or others) by achieving all our goals in every way every day.

The man who brought the Slow movement to global prominence is Carl Honoré, a journalist whose 2004 book, In Praise of Slow, cast a spotlight on the degrading effects of our too-speedy lifestyles. The Slow movement has no official overseer, but if it did, Honoré would be His Supreme Slowness. Recently, I got him on the phone from his home in London.

“The pandemic is the largest experiment in Slow the world has ever seen,” he said. “It’s a nightmare, but there is a good side to it. People are now more into Slow pursuits like biking, baking bread, sitting around the table with their family.”

He told me that “if there’s been a failing in the American model, it’s the tireless working and commuting. For many, the pandemic is a reminder of what actually matters in life. There’s been a gathering revulsion against the way things were.”

Honoré’s observations carry the weight of authority. Consequently, I am allowing them sufficient time to sink in.

In the last issue, Cable wrote about all-you-can-eat buffets.

This article is featured in the September/October 2020 issue of The Saturday Evening Post. Subscribe to the magazine for more art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

Featured image: Shutterstock

Your Health Checkup: COVID-19 and Other Pet Health Concerns

“Your Health Checkup” is our online column by Dr. Douglas Zipes, an internationally acclaimed cardiologist, professor, author, inventor, and authority on pacing and electrophysiology. Dr. Zipes is also a contributor to The Saturday Evening Post print magazine. Subscribe to receive thoughtful articles, new fiction, health and wellness advice, and gems from our archive.

Order Dr. Zipes’ new book, Bear’s Promise, and check out his website www.dougzipes.us.

I love animals and have had dogs as pets for many years. It’s important to keep your pets healthy since on occasion they can make you sick through bites, scratches, or other direct contact of human skin or mucous membranes such as the mouth or tongue. Other sources of exposure include contact with animal saliva, urine, and other body fluids or secretions, inadvertent ingestion of animal fecal material, inhalation of infectious aerosols or droplets, and through the bite of a spider, flea, tick, and other similar vectors harbored by the pet.

The following are some examples of the more than 70 diseases in humans that can be caused by animals.

- COVID-19 is known to spread from humans to dogs and cats. While there is no credible information that the animal can pass the infection back to humans, an abundance of caution suggests you should isolate from your pet if you become infected with the COVID virus.

- Ringworm is a contagious fungal infection that presents as a circular rash and can be spread to humans from many different animals as well as from human to human. It is usually treated with topical antifungal agents.

- Lyme disease is caused by the bite of blacklegged (deer) ticks infected with the bacterium Borrelia burgdorferi. While dogs and cats with Lyme disease cannot spread it to humans, they may harbor the ticks in their fur that can infect humans.

- Parasitic worms such as roundworms can infect dogs and cats and be passed to humans in animal feces containing worm eggs. Careful disposal of animal excrement while wearing gloves and thorough hand washing is recommended.

- Cat scratch fever is an infection caused by the bacterium Bartonella henselae, and is carried by 40 percent of cats at some point in their lives. It is spread to humans by cats licking an open wound or a scratch or bite that opens the skin. Avoiding cats licking an open wound and washing a cat scratch or bite thoroughly with soap and water and applying an antiseptic is recommended.

- Toxoplasmosis is caused by a microscopic parasite, especially common in cats, that can spread to humans in contact with the animal feces. It can cause significant harm to the fetus in pregnant women but is typically not significant in otherwise healthy people. As noted above, careful cleanup of animal feces such as the cat litter box is a must, and pregnant or soon-to-be-pregnant women are advised to avoid cleaning the litter box at all.

- Leptospirosis is caused by a bacterium found in the urine of many animals and can spread to humans in contact with the animal urine or drinking infected water.

- Salmonellosis is usually a gastrointestinal infection caused by a bacterium that lives in the intestinal tract of animals. While salmonella infection is most commonly transmitted by ingesting infected food sources, pets such as chickens and other birds, turtles, frogs, dogs, cats, and horses can transmit the disease.

- Psittacosis is bacterium causing parrot fever from infected parrots, pigeons, and many species of birds that presents as a severe pneumonia. The infection routes are by mouth-to-beak contact, or through the airborne inhalation of feather dust, dried feces, or the respiratory secretions of infected birds.

- Methicillin resistant staph aureus bacterial infections can be transmitted from dogs, cats, birds and other animals to humans and vice versa.

- Rabies is a deadly virus spread to humans in the saliva of an infected animal, usually transmitted through an animal bite.

How to Prevent Infections from Animals to Humans

- The number one recommendation is to wash hands vigorously after contact with animals or their waste

- Keep a pet healthy and free from infections with appropriate vaccinations, flea and tick prevention, and regular veterinarian checkups

- Wear gloves to clean up animal feces and wash hands thoroughly afterward

- Dispose of animal waste in plastic bags in appropriate containers

- Wash pet bedding regularly and clean litter boxes or cages frequently

- Clean high contact surfaces such as countertops and tables and avoid food contamination with pet waste

- Don’t let animals lick human open wounds or mucous membranes (e.g. mouth, tongue)

Pets are wonderful companions and help us live longer, healthier, and happier lives. Enjoy them, love them, but remember that certain precautions to keep you and your pet healthy are warranted.

Featured image: shulgenko / Shutterstock

Con Watch: A Continuing Pandemic of Scams — Phony Antibody Tests

Steve Weisman is a lawyer, college professor, author, and one of the country’s leading experts in cybersecurity, identity theft, and scams. See Steve’s other Con Watch articles.

The Coronavirus pandemic continues to spread throughout much of the country with many states facing serious increases in the numbers of infected people and crowded hospital intensive care units. With no vaccine presently in sight, much attention has been focused on antibody tests for COVID-19. A proper antibody test can determine if you have developed antibodies against COVID-19. Antibodies are typically a sign that you have previously been infected with the virus. While many people assume that the presence of antibodies means that you are protected from future infections by COVID-19, researchers are still studying whether or not this is true and, if so, for how long such immunity would last. Still the attraction of a positive antibody test is easy to understand.

Legitimate antibody tests are available, but it’s no surprise that scammers are jumping on the bandwagon and trying to sell you bogus tests that not only are worthless, but can make you a victim of identity theft. The FBI recently issued a warning about these scams.

Scammers often falsely claim that the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved their test. Fortunately, it’s easy to confirm with the FDA whether or not the test being offered is an approved test. The FDA lists the actual tests that they have authorized.

Phony antibody tests are offered through phone calls, emails, text messages, and social media posts. You should immediately be skeptical of any antibody test being offered through these means because you can never be sure as to who is really contacting you. Through a simple technique called “spoofing” a scammer can pose as a public health official and manipulate your caller ID to make it appear that the call is from a legitimate source. Similarly, text messages, emails, and social media posts can all be easily hacked to appear to come from a reliable source when they actually are coming from a scammer. Trust me, you can’t trust anyone.

You should be particularly wary of anyone who contacts you offering a free antibody test or even offering to compensate you for taking such a test. These offers are used to gather information that can make you a victim of identity theft.

Never provide your Medicare or other health insurance information to someone offering an antibody test unless you have absolutely confirmed that the offer is genuine. Your Medicare identification number or your health insurance policy information can be sold on the black market, which can have dire consequences when an imposter’s information becomes mixed in with your medical records.

Before taking or purchasing any kind of antibody test, you should first confirm that the test is approved by the FDA. Most importantly, consult with your primary care physician about taking such a test. You also should make sure that the laboratory doing the test is one approved by your health insurance company and confirm that they will cover the cost of such a test.

Featured image: Monika Wisniewska / Shutterstock

You Can Change Your Life After COVID-19, But it Will Be Difficult

I stand by my general statement that most people won’t change because of their experiences during this lockdown. There are simply too many forces that will push most of us back to our old behaviors, habits, and routines.

But just because most people won’t change doesn’t mean that you aren’t capable of using the COVID-19 crisis as an opportunity to make significant changes in your life. It certainly won’t be easy, but I would be negating my professional life if I didn’t believe that you could take the healthy lessons you learned from being forced to change your life during the pandemic and continue those changes as you leave the safety of your own home and return to life as we have known it.

The challenge is how, despite the forces stacked against you, can you make those changes you want permanent. Let me begin the “how” of making the changes in your life permanent (or at least enduring beyond the shutdown) by reminding you of the obstacles you face in making significant changes to your behavior:

- Your behaviors, habits, and routines are deeply engrained through repetition and reinforcement

- You will return to all of your regular institutions (work, school, extracurricular activities) after the shelter-in-place is lifted

- There is implicit pressure from those in your various communities to conform to the social norms that everyone else is returning to

- You will have a plate full of activities that you haven’t been able to do during the lockdown that you need to do now that our world is “re-opening” again

- There are many activities that we want to do that we couldn’t during shelter-in-place

- Most of us chose our lives before the COVID-19 crisis, which means that we enjoyed many aspects of who we were and what we did

With those challenges identified, I want to provide some perspective on how the degree of change you want to make will impact your ability to make those changes. I’ll start with the premise that few of us are going to use this opportunity to turn our lives upside down. For example, it’s not likely that many of us will sell our worldly possessions and move our families to northern Idaho and live in a yurt (or some equivalent thereof). Again, given that you had chosen your life before the pandemic, the changes you might want to make are likely more around the edges than a wholesale re-creation of your life.

I also want to establish some realistic expectations about what lies ahead for you if you are truly committed to making significant changes to yourself and to your life as the COVID-19 crisis winds down (hopefully). I’m going to say it simply and clearly so you don’t miss the message: Change is difficult, very difficult; otherwise, we would all change every unhealthy behavior, habit, or pattern we’ve ever developed. And there would certainly not be a $10 billion self-help industry in the U.S. alone if change was easy. Despite my cynicism, I do believe that people can change themselves and their lives for the better; gosh, I wouldn’t have a career if I didn’t!

Having established a realistic perspective and reasonable expectations, now we can dive into a process for how you can actually get the positive changes you’ve made during the pandemic to stick while living in the post-pandemic “new normal.”

Step#1: Identify the Way You Have Been

With the simpler and less busy life you’ve been leading during the lockdown, the aspects of your life that you have seen as unpleasant, unproductive, or downright unhealthy likely came into sharp relief. You’ve likely learned that you don’t like some aspects of yourself, and this downtime showed you that you are capable of not being that way; for example, you might find that you are less stressed, more fun, or healthier.

The first step in the change process is to clearly identify what elements of yourself or your life you don’t like and don’t want to continue post-COVID. You can gain this understanding by recognizing your past less-than-desirable self (thoughts, emotions, behaviors, interactions) and observing your much-more-desirable current self. I also encourage you to get feedback from family and friends about your past and current self. Hopefully, this juxtaposition will demonstrate starkly the way you don’t want to be and the way you want to be, which will hopefully inspire and motivate you to make the changes you’ve made during the COVID-19 crisis permanent.

Step #2: Identify the Change

You want to identify the very specific aspect of yourself that you want to change. It might be a counterproductive way of thinking (too self-critical), feeling (too angry), behaving (overeating), or interacting with others (too authoritarian with your children).

Also, as part of this first step, you want to articulate in detail what you have been thinking, feeling, and doing during the lockdown and what you want to think, feel, and do as you unlock your life; for example, more self-supportive, calm, loving, or active.

Step #3: Identify and Remove Obstacles

A simple reality of this process is that all of the motivation in the world won’t enable you to make the changes you want if tangible obstacles stand in your way. To successfully achieve change in your life after the pandemic, you must clear or at least minimize their impact on your efforts. Referring back to the bulleted list above, first, identify the behaviors, habits, routines, institutions, pressures, and activities whose collective momentum will attempt to pull you back on your pre-COVID life trajectory.

Second, you can look for ways to remove these obstacles from your path to change. Ask yourself how you can surmount those barriers by continuing to remove self-defeating emotional triggers, disrupt your routines, choose other institutions to be a part of, focusing on your values and priorities rather than being concerned what choices other people are making, and deciding that some activities you might otherwise feel you need to return to aren’t really that important.

Step #4: Set Realistic Goals

Recognizing that the changes you want to continue in your life post-pandemic will be difficult, you can establish realistic goals that will encourage you to stay committed to the changes you want to make. Identify the end goal of the life you want to lead and then reverse-engineer more proximal goals that keep you motivated and focused on those changes every day. Then, regularly reward yourself for your accomplishing those goals.

Step #5: Enlist Support

Enlisting support from important people in your life is an essential step in keeping the momentum of change alive as you transition to post-COVID. Another simple reality is that if your significant others don’t support or, even worse, undermine your efforts at change, you’re dead in the water before you even begin.

I encourage you to identify key people in your world, share your vision of change, and ask them how they can support you. Even more powerfully, try to get them on board with the changes, especially your spouse, children, other immediate family, close friends, and co-workers who can have a direct impact on the changes you want to make.

Step #6: Take Action

Without putting the above into play, everything is just talk and you will soon slip back into the old you and your old life. After all of that preparation, it’s time to take action. I suggest that you ease yourself into the changes you want to make rather than try to go “cold turkey.” Give yourself time to become familiar and comfortable with the changes you want to make. Also, recognize that you will likely have setbacks and may fall off the wagon periodically because old and ingrained ways of being and living die hard (but know that they will die in time).

For example, you could put your children in recreational sports leagues instead of the traveling teams that they were on before COVID struck, place them in a nearby school they can walk or bike to, commit to buying healthy food, continue to work from home, prioritize exercise, the list goes on and on.

Step #7: 1 C & 3 Ps

As you make the transition from the COVID-19 crisis to a return to normal life, you need four letters to keep you on track. The first letter is C, as in commitment. For you to make stick the changes you’ve enjoyed during the pandemic, you need to have a moment-to-moment commitment to taking action on your change goals. You can expect to be constantly pulled back to the old road you were on in your life and, when this occurs, you must resist with all your might and choose the fork in the road that will take you down this new and healthier life path.

The second is P is for patience. As I’ve noted several times before, change is difficult and it is also slow. There are no quick fixes or instant successes with change. If you become impatient with your rate of change, you will become frustrated, then angry, then despairing, at which point you will likely give up your efforts at a new and improved you. If you maintain a long-term perspective, recognize that it will be difficult, yet have faith that you can make the change lasting, you will show the patience you need to stay committed to your new life path.

The third is P is for persistence. This quality is one of the most important for changing your life. The people who are successful in any aspect of their lives are those who just “keep on keeping on.” Day in and day out, week in and week out, month in and month out, they stay committed and just keep plugging along until their lives are truly changed.

The fourth is P is perseverance. Another essential quality to successful life change because you will inevitably, as I noted above, fall off the wagon, have setbacks, and experience outright failures in your journey to the kind of person you want to be. It’s simple, though far from easy; every time you fall down, you get back up and keep putting one foot in front of the other toward the person you want to be and the life you want to lead.

In sum, the COVID-19 crisis will, in time, pass. When that happens, you will have to decide whether you want to stay on the same road as you were on before the pandemic or you want to choose another road that involves changes to who you are and the life you are leading.

Want to learn more about how to respond to the COVID-19 crisis in healthy and constructive ways? Read Dr. Jim Taylor’s new book, How to Survive and Thrive When Bad Things Happen: 9 Steps to Cultivating an Opportunity Mindset in a Crisis, listen to his podcast, Crisis to Opportunity (or find it on Stitcher, Spotify, iTunes, or Google), or read his blog about the COVID-19 crisis.

Featured image: Shutterstock

13 Virtual Festivals and Events This Summer

Summer is the time for rushing to crowded places to celebrate and experience culture. The best festivals and events in the country should be taking place in the next few months, but gathering hundreds of people together is ill-advised. Instead, lots of organizers have adapted their events to be experienced virtually. On the bright side, this could give even more people access to art, comedy, films, and other cultural events.

Great Smoky Mountains National Park Firefly Light Show

Each summer, the Great Smoky Mountains National Park lights up with 19 species of bioluminescent beetles, also known as fireflies. From late May to mid-June, a particular type of firefly flashes synchronously in the night during its mating season, and visitors flock to the park to witness the stunning display. Although the event was cancelled this year, Discover Life in America created a virtual experience with photographer Radim Schreiber so that anyone can see the natural light show from their own home.

The Pandemic Faire

This virtual art fair curates work from contemporary artists located around the globe for visitors to browse in lieu of attending art festivals in the real world. With new artists added weekly, the Pandemic Faire offers art lovers exposure to new creators along with links to purchase their work from galleries and personal websites.

Second City Online

The Chicago-based improvisational comedy troupe is offering a slew of free virtual programming for you to enjoy “from the discomfort of your own home.” By registering for the live performances with Zoom, attendees can watch and take part in weekly improvisational shows like Improv House Party, Girls Night In, and the family-friendly Really Awesome Improv Show Online. Second City has also released The Last Show Left on Earth, a four-episode YouTube variety show with sketches and musical guests (the first episode features one of the last appearances of the late, great Fred Willard).

All In WA

The first place in the U.S. to be hit hard by COVID-19, Washington state, has seen philanthropists and communities come together to organize a virtual concert to benefit its workers and families who have been hit hardest by the pandemic. All In WA is collecting donations to go toward food and housing insecurity in the state, and the concert, to be livestreamed on June 24, will feature Pearl Jam, Ciara, Macklemore, Dave Matthews, and more.

Blue Ox Music Festival

In Eau Claire, Wisconsin, the Blue Ox Music Festival has brought bluegrass and Americana musicians to this family-friendly event since 2015. Although the festival will lack a live audience this year, the acts will still be livestreamed on YouTube on June 12 and 13. Sam Bush, Pert Near Sandstone, Charlie Parr, and Them Coulee Boys will perform, and Chicago-based bluegrass band The Henhouse Prowlers will give a talk about their experience teaching music in the U.S. and abroad.

Juneteenth

June 19th, the anniversary of the end of slavery in the U.S., is widely celebrated around the country. Denver’s celebration, which includes a music festival, awards, comedy, and financial literacy segments, will be livestreamed on June 18. Their celebration of African-American history also comes with a call to make Juneteenth a national holiday.

Stretching Arms

Through July 31, A Women’s Thing is holding an online exhibition and auction called “Stretching Arms.” The collection features young women artists from New Zealand, Russia, China, and Belarus and asks the question, “How do we transcend solitude?”

Electric Blockaloo

A rave, experienced through the videogame Minecraft, is calling itself “the world’s largest virtual music festival.” With more than 300 electronic artists and digital recreations of music venues and mini-games, admission to Electric Blockaloo on June 25-28 will require “guest list” links from artists distributed via social media.

Seattle Festál

Seattle’s summer (and fall) of cultural festivals will be taken online. The Chinese Culture and Arts Festival, Black Arts Fest, Iranian Festival, and more will offer dancing, art, workshops, and classes to anyone wishing to “make 2020 memorable for the resilience and beautiful moments of humanity,” and you don’t have to be in Seattle to enjoy it all.

CPR Summerfest

Colorado Public Radio’s annual festival of classical music features world-class musicians and singers performing for 10 weeks each summer. This year, CPR is bringing in Joshua Bell, the National Repertory Orchestra, and some of Colorado’s own musical institutions to keep classical selections playing all summer. You can tune in online or by using a smart speaker.

NYC Dance Week Virtual Fest

Dance studios in New York City are offering free dance classes from June 11-20, and they’re open to everyone everywhere. Ballet, yoga, jazz, hip-hop, and tons of other fitness lessons are on offer from a host of studios. If you ever wanted to try a professional class (or 10), this is your chance to do it with no commitment or cost.

Key West Mango Fest

If you were wondering what to do with all of those extra mangoes you have lying around, Key West Mango Fest might have a virtual answer for you. Join in on virtual cooking and cocktail demonstrations, contests, and shopping that revolve around the “king of fruits.”

deadCENTER Film Festival

Oklahoma City’s 20th annual film festival will be going virtual (with some possible drive-in options). By purchasing an all-access pass or individual tickets, you can stream the shorts, music videos, and feature films as well as see panels and workshops with filmmakers from around the globe.

Featured image: Shutterstock

What Happened to the Summer Movies?

“Summer Movie Season” has been a familiar notion in America for decades. That’s when the crowd-pleasing blockbusters and movies targeted at the kids who are fresh out of school hit the screen. Since the early 2000s, the start of Summer Movie Season kicks off the first weekend in May as studios tie genre releases to Free Comic Book Day to give their big-tent films an extra boost. However, with the COVID-19 pandemic still ongoing, the Summer Movie Season had to make radical adjustments, resulting in three parallel narratives: the push of some films to fall dates, the shifting of other films to streaming platforms, and the unlikely success of “The Wretched” (and now, “Becky”) at drive-in theatres. Sit back, ladies and gentlemen; we’ve got ourselves a triple feature.

Part I: Where Did the Movies Go?

As with any regular summer season, the summer of 2020 was set to be chock-full of blockbuster movies. Those included Mulan, A Quiet Place 2, Black Widow, James Bond installment No Time to Die, Scoob!, Wonder Woman 1984, Pixar’s Soul, Top Gun: Maverick, Ghostbusters: Afterlife, and more. When the threat of the pandemic became clear in March, studios began rapidly moving pictures to other dates or, in some cases, to other platforms. With some indoor theater chains preparing to open in June, we can take a look at where some of these expected big movies have settled. (Note: Dates may still be subject to change.)

The trailer for Tenet. (Uploaded to YouTube by Warner Bros. Pictures)

- Mulan: July 24

- Tenet: July 31 (Updated: Tenet moved back after this article posted.)

- The Spongebob Movie: August 7

- Wonder Woman 1984: August 14

- The Secret Garden: August 14

- Antebellum: August 20

- Bill & Ted Face the Music: August 21 (This is also the original date.)

- New Mutants: August 28 (This is the fifth date for this film. It’s a long story.)

- A Quiet Place 2: September 4

- Candyman: September 25

- Without Remorse: October 2

- The French Dispatch: October 16

- Fatherhood: October 23 (This Kevin Hart film actually moved up from January of 2021.)

- Black Widow: November 6

- Soul: November 20

- No Time to Die: November 25 (Update: This date changed after the article posted.)

- Free Guy: December 11

- Top Gun: Maverick: December 23

The trailer for In the Heights. (Uploaded to YouTube by Warner Bros. Pictures)

Additionally, a number of anticipated films were moved out of 2020 completely. Here are anticipated 2020 openers that ended up shifting to 2021.

- Peter Rabbit 2: The Runaway: January 15

- The Eternals: February 12

- Ghostbuster: Afterlife: March 5

- Raya and the Last Dragon: March 12

- Morbius: March 19

- F9 (Fast & Furious 9): April 2

- Shang-Chi and the Legend of the Ten Rings: May 7

- In the Heights: June 18

- Venom: Let There Be Carnage: June 25

- The Tomorrow War: July 23

- Jungle Cruise: July 30

- Minions: Rise of Gru: July 2

- Mission: Impossible 7: November 19

- The Nightingale: December 22 (Note: This is the Dakota and Elle Fanning WWII drama, not the 2018 Australian film.)

Part II: Where Did the Movies Go on Streaming?

The trailer for Working Man. (Uploaded to YouTube by Brainstorm Media)

As a subset to all of the big date moves for theatrical releases, a number of films were pulled to be released onto VOD or various streaming services. Some have already debuted, while others are on the way. Here are some of those notable switches.

- Trolls 2: World Tour: Digital Rental on April 10

- Blue Story: Digital Rental on May 5

- Working Man: Digital Rental on May 5

- Scoob!: Digital Rental on May 15

- The Lovebirds: Netflix on May 22

- Artemis Fowl: Disney+ on June 12

- Irresistible: Digital Rental on June 26

- Hamilton: Disney+ on July 3

- The Truth: Digital Rental and select theaters on July 3

- Greyhound: AppleTV+ (date pending)

- My Spy: Amazon (date pending)

Part III: How did The Wretched become the #1 movie in America?

As theater chains and local movie houses shut down due to the pandemic, one particular type of venue did manage to start showing films again. That was, of course, the drive-in, where social distancing is built in to the experience as you watch the film from your own car or parking space. As the Post previously reported in 2018, drive-in theaters have experienced something of a minor resurgence in recent years; the pandemic gave those in operation the unique ability to deliver movies when everything else was closed.

The trailer for The Wretched. (Uploaded to YouTube by FilmSelect Trailer)

Of course, the vast majority of big summer releases had already been moved. That gave some smaller films the opportunity to get in front of drive-in viewers eager for a movie experience. Enter Brett and Drew T. Pierce’s horror film, The Wretched. The IFC Films picture premiered at the 2019 Fantasia International Film Festival; it’s received mostly positive reviews with particular praise for its cinematography and atmosphere. On May 1, The Wretched arrived for digital rental . . . and at drive-ins. By the end of the weekend, with essentially no competition from indoor theaters and few other new films on the outdoor screens, The Wretched hit #1 at the box office, pulling in over $65,000 from 12 screens. For the next four weeks, The Wretched sat atop the box office charts, making more money every week as more outdoor screens added the word-of-mouth hit. It was finally dethroned in week six (although it made over $200,000) by the debut of Becky, a thriller featuring burgeoning horror starlet Lulu Wilson.

The success of The Wretched is something of a throwback to the 1950s through the 1980s, when lower-budget films released at drive-ins could still thrive. This is actually a hopeful sign for the movie business, as it might re-open the way for reliable distribution across models; instead of being locked in to indoor theatres, films could consider different viable options for release and still have scaled tiers of success. Certainly, a hugely budgeted Marvel movie couldn’t necessarily make what it needs to by relying solely on drive-ins, but a $1 or $2 million-budgeted thriller could do quite well. If there’s a sustained COVID-19 spike over the summer, drive-ins may be the only places (outside the home) where new films are available.

Like all avenues of American life in 2020, the movies had to adapt quickly to a new normal. And while nothing’s back to the “old normal” yet (and may not be for some time), it’s refreshing to know that there are still pathways for people to embrace escapism. Whether you prefer your films under the stars or in the comfort of your home, it seems that you have plenty of options coming to a screen near you, even if you have to wait a little longer than you expected.

Featured image: Shutterstock

Con Watch: Confusion with Stimulus Payment Debit Cards