Can a Retired Vaccine Company Executive Change How We Think About Pandemics?

As the United States passes another grim milestone with more than 100,000 deaths due to COVID-19, one scientist thinks his idea could have saved lives. And may yet save lives in pandemics to come.

In a small village in France, Dr. David Fedson has been working for the past 16 years to promote a cost-effective strategy of using generic drugs to combat a pandemic.

“If we ran trials on promising drugs before the pandemic and found this approach to treatment didn’t work, well, so what? I was wrong,” Fedson says. “But if, after the pandemic, the research confirms that this approach actually does work, and then we look back at all those people who died unnecessarily, we’re going to feel very bad indeed.”

Drugs such as statins (a cholesterol lowering medication) as well as ARBs and ACEIs (blood pressure medications) are the drug types that he advocates running clinical trials on, as stated in his 2020 medical paper, “Hiding in Plain Sight: An Approach to Treating Patients with Severe COVID-19 Infection,” and other published work. While not averse to vaccines, he sees the mounting death toll as a case in point that to fight a pandemic there needs to be a medical option on “day one,” when the virus first starts spreading.

“The only way to effectively confront a pandemic is to figure out a way to use what we already have,” Fedson says. “Drugs that are generic, inexpensive, and that doctors use every day in their practices.”

Fedson is a retired professor of medicine from the University of Virginia who also served as the medical director at Aventis Pasteur, a European vaccine company. He saw the weakness of a vaccine-only approach to an influenza pandemic back in 2001 when he was instrumental in establishing the Influenza Vaccine Supply International Task Force.

“The whole purpose of the task force was to get the companies we worked for — and the top-tier executives running them — to pay attention to the fact that someday we would have an influenza pandemic,” Fedson says. “And it became quite apparent to me that the global capacity to manufacture pandemic vaccines just wasn’t there. By the time the vaccines would become available, it would be too late.”

Dr. Alice Huang, a virologist and former Harvard Medical School professor who was involved in developing a vaccine for HIV, confirms that an approved vaccine for the coronavirus will take time.

“We all really need something sooner rather than later, but in my experience with making a vaccine…it takes a long, long time,” Huang says. “And when you read about people saying that it would take about a year to 18 months, that is if everything goes perfectly right.”

Fedson recounted an early career experience treating cholera patients in India, not by targeting the pathogen, but focusing on keeping the patients alive long enough so they could overcome the worst effects of the disease.

“I spent three months on the Johns Hopkins Cholera Unit in Calcutta as the team fine-tuned a formula to rehydrate cholera patients, a breakthrough that has saved tens of thousands of people ever since,” Fedson says.

What made it effective is that the rehydration treatment could be lifesaving not just for cholera patients, but also for those suffering from severe diarrhea caused by other diseases. Regardless of what brought on the severe diarrhea — it could be a virus, shigellosis, or any number of other infections — the same treatment would keep the patients alive long enough until their own defenses took over and the diarrhea stopped.

The same concept of focusing on the well-being of the host instead of defeating the pathogen may be applied to treating COVID-19 as well.

In the case of COVID-19, when the immune system becomes compromised, its response can be too strong, causing a self-destructive form of inflammation that has been dubbed the “cytokine storm.”

Cytokines are small chemical messengers that tell the immune cells of the body to become activated, so they are ready to fight the virus. As is increasingly evident in some COVID patients, when that inflammation occurs in the alveoli of the lungs — the air sacs critical for delivering oxygen throughout the body — it can cause acute respiratory distress (ARD) and death.

Dr. Brian Ward, a professor at the Centre for the Study of Host Resistance at McGill University, who specializes in immune system response, says that a virus usually does not kill its host, but that COVID-19 is behaving atypically.

“It’s a weird virus; it’s not like many of the other viruses that we deal with,” Ward says. “Even though we’re closing in on one and three-quarter million people infected in the U.S. and five and one-quarter million worldwide, we do not yet have a clear idea of why some people seem to walk through the illness and other people get into real trouble really fast. And certainly, the idea of the body’s reaction, the so-called cytokine storm theory, is one of the hypotheses for that late inflammatory reaction in the lungs.”

Worldwide, there are currently more than 337,000 confirmed fatalities due to COVID-19 according to the World Health Organization’s May 24, 2020 coronavirus situation report, with the numbers likely to rise.

Instead of making the virus the primary target, which is what vaccines and antivirals do, Fedson says the top priority is to find a cost-effective generic drug — or a cocktail of drugs — that will reduce some of the worst consequences of the immune system’s overly zealous response to the virus and save lives.

“We’re talking about a way of treating people with acute critical illness due to any cause, and it can be a pneumonia, ARDs, it can be bacterial sepsis, it can be viral diseases, it can be lots of things that cause people to be hospitalized and get into ICUs,” he says. “The wonder and the beauty of it is that we’re using generic drugs that are available to people in Bangladesh, just as they are available to people in Boston.”

In the midst of the pandemic, Fedson’s idea may finally be gaining traction. Investigators at numerous U.S. universities — as well as in several countries outside the U.S. — have undertaken trials of angiotensin II receptor blockers (ARBs), a kind of cardiac medication that Fedson says might be especially effective when “repurposed” for use in pandemic illness. ACEIs and statins are being studied as well.

Two of the most important and innovative of these trials on ARBs are now underway with COVID-19 patients at the University of Minnesota trialing the blood pressure medication Losartan. As an ARB, Losartan blocks activity on a receptor site that raises blood pressure. It is possible that blocking this receptor will also diminish inflammation and reduce damage to the lungs of COVID patients.

“Losartan has an established safety profile and is readily available,” says Dr. Chris Tignanelli, an assistant professor at the University of Minnesota Medical School overseeing the trials and administering the drug to both in-patients and out-patients. “We wanted to test a readily available, cheap, FDA-approved generic drug with potential efficacy against COVID-19.”

Tignanelli was initially swayed by promising reports written by doctors in China who observed “a one-third reduction in lung injury” in SARS-infected lab mice who were given Losartan. The current trials are financed in part by the COVID-19 Therapeutics Accelerator Funds — a Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation initiative.

Dr. Michael Puskarich, the other doctor running the University of Minnesota’s randomized control trials, also sees potential for Losartan.

“Losartan is different from the other treatments being tested right now — it’s not an antiviral medication,” Puskarich says. “We’re trying to prevent the lung injury caused by the virus that makes it so deadly. We’re trying to turn COVID-19 into an everyday coronavirus, the common cold.”

The cost for a typical regimen of Losartan (14 tablets) is $15. Tignanelli says Losartan most likely will not be a “miracle drug,” but could be used as part of a cocktail of drugs.

“The story probably won’t end with Losartan,” he adds. “I doubt that any single drug is going to be a magic bullet as we’re probably going to need some combination of anti-inflammatory drugs targeting different parts of the immune pathway.”

Drug cocktails are something that hospitals such as St. Luke’s University Health Network in Pennsylvania are administering to their COVID-19 patients. At St. Luke’s, doctors have used a combination of vitamin C, zinc, atorvastatin, and steroids, as well as high-flow nasal oxygen and other pioneering approaches.

“Of course, the concept of using cheap drugs makes perfect sense, even to a random person on the street,” Fedson says, recounting a woman he met on a bus pre-pandemic who agreed it was worth a shot. “Unfortunately, she is not the president of the United States, and she’s not the director of the NIH [National Institutes of Health], or the director of the CDC [Centers for Disease Control], or the director-general of the WHO [World Health Organization]. I wish she were. If she had been, we would be much better off today than we are.”

Featured image: Shutterstock

A Normal Sunday in Speedway: Missing the Indianapolis 500

Last Sunday, the engines didn’t roar to life, drowning out the sound of over 300,000 people cheering in unison. Thirty-three of the world’s finest drivers didn’t battle it out, mere inches apart, for 200 laps, around a track that’s over a century old. Celebrities from all different facets of the entertainment industry didn’t flock to the town of Speedway, Indiana, which — on a normal day — has a population of about 12,000 people. Because that’s all that last Sunday was, in Speedway, Indiana: a normal Sunday. It wasn’t supposed to be. Last Sunday was supposed to be the 104th running of the Indianapolis 500, but, because of the precautions taken due to the coronavirus, the race has been delayed until August.

While those who have never been to the race may balk at it, deriding it as a redneck sideshow or a relic of a bygone era, those who make the trek to central Indiana every Memorial Day weekend view it very differently. As the famous author, John Green (The Fault in Our Stars) points out on his podcast, Anthropocene Reviewed, there is much more to the historic race than meets the eye. Green points out that the race — which in its 100th running in 2016 drew somewhere north of 350,000 people — is the largest non-religious gathering of people in the world. It clearly holds an allure far beyond people merely interested in seeing cars go around a circle for 500 miles.

I suspect it’s the tradition. Countless fans I’ve spoken with in my years of attending the race proudly share stories of their seats. The same seats they’ve had their whole life. The same seats their parents had before them. People compare memories of races past, and show off the paraphernalia they’ve collected over the years. People tear up as Jim Cornelison sings Back Home Again, In Indiana, appreciating a job well done, but still missing Jim Nabors. Racing’s biggest legends, like Mario Andretti, will navigate the crowds, signing thousands of autographs along the way, and taking just as many selfies. Parents of young children beam as their kids experience the sound and power of cars traveling over 230 miles per hour. Most of all, people revel in these shared experiences — the community that everyone in attendance creates in watching a single event, together. All in attendance share that bond, for the rest of their life. Whether it was watching a hot-shot rookie from F1, Alexander Rossi, win the 100th race in 2016, or seeing Al Unser Jr. and Scott Goodyear battle it out in 1992 for a win that would have surely gone to Michael Andretti had it not been for a mechanical issue late in the race; all those in attendance share that experience forever.

That’s what makes this delay so hard for so many. It’s not that we’re missing a race, it’s that we’re missing a shared moment. Perhaps it’s that we all must be so distant these days that makes the lack of this community so much more apparent. It would be easy to feel despair, but I don’t. The Indianapolis 500 has been cancelled before, admittedly for World War I and World War II. So, I take solace in the fact, that when this is behind us, the Indianapolis 500 will return. I don’t know when; it’s currently scheduled for August of this year, and I certainly hope that will be the case, but it’s far from a certainty, given the nature of this pandemic.

Regardless, I know it will be back. I know that we will once again gather in that small town just outside of Indianapolis. We will once again weather the seemingly endless line of cars trying to get in, eventually parking in the “secret spot” we all seem to have found in a nearby neighborhood. We will walk under the tunnel, or to our grandstand seats. Will hear those famous words, “start your engines.” And, when those engines start, we won’t hear much of anything else. On the way out, in the throngs of people finding their way to their cars, we will share our stories of races past. Stories of Marco Andretti’s heartbreaking second-place finish, and a curse that we all want to end. Stories of Dan Wheldon’s win, and a great man gone too soon. We’ll talk about winners old, and new; and those who probably should have won, but never did. And we’ll talk about this year. We’ll talk about a virus that delayed the Greatest Spectacle in Racing. And we’ll talk about how we all got through it: together.

Featured image: Jonathan Weiss / Shutterstock.com

Funeral Service in the Time of COVID-19

On a chilly and rainy day in late April, I stood at a grave in Queens County, New York, with three mourners in protective masks, preparing to lead the graveside prayers. The casket had already been lowered, unlike how it has always been done, and it hit me that I would be praying to a hole.

The family members, who had come from Long Island to bury a 97-year-old grandmother, seemed to come to the same realization. They peered down uncomfortably into the grave, at the steel vault that covered the casket. There had been no church service or wake. And, now, they could not even be close to the casket that held their loved one’s remains.

I felt responsible, as if I were the one letting them down. But my discomfort at being unable to serve people properly was a fleeting bad moment in three draining months that have taken their toll on people like me who make their living as funeral directors. The deaths keep coming. And we keep doing our jobs. Unlike our fellow citizens, who can look away and find escape in not confronting the reality, we cannot.

As I spoke to other funeral directors in New York about what they have been going through, the same themes emerged time and time again: trying to cope as the wave of death overwhelmed us, finding a renewed sense of duty to the dead as families were kept away, fighting impossible odds to keep bodies from going unattended or shipped off to a potter’s field.

In the months preceding the U.S. outbreak, we all had watched the news of the pandemic as it played out in China and Italy. We were curious about how these countries were dealing with their dead. Perhaps it was a mix of wishful thinking and naivete that made us think, “That could never happen here.” Until it did, thrusting us into death overload by early April.

Funeral homes in the five boroughs of New York quickly became filled to capacity. As the pandemic gripped the city, the death toll in New York City reached almost 20,000 and funeral homes were forced to turn away scores of frantic families looking to bury their dead. They had neither the staff, nor capacity, to handle the surge of deaths. The city was prepared to send remains to New York City’s own potter’s field, on an island in the East River. The city order was later rescinded, but it only fueled our ever-present sense of urgency.

We all came to share grim accounts of what death had become in New York.

In Brooklyn, as a funeral home van made its way down a city street, residents called out to the driver from the sidewalks. “People were trying to flag it down because they have dead bodies in the house and the medical examiner’s not answering the phone,” Tom Libraro wrote on his Facebook page. “It just showed the desperation of people when the morgue attendants couldn’t handle it,” said Libraro, who works at Brooklyn Funeral Home & Cremation Service.

Anthony Cassieri, who owns Brooklyn Funeral Home & Cremation Service, usually handles about 450 funerals in a year. In the past month alone he has done 149.

“We couldn’t get the bodies embalmed fast enough for the people who were having viewings. There was no outlet for crematories. And we didn’t have the space to keep people.

“I had to close down for ten days to regroup,” says Cassieri. He didn’t want to be rendered as little more than a “body disposer.”

“We were still taking calls and talking to people,” he says. “Some were begging for help, telling us that they’d called 21 funeral homes, but no one could help us.”

“It’s not that we don’t want to help you. We can’t,” he and his staff told callers.

To store the bodies, Cassieri rented a refrigerated truck. Those trucks became an arresting sight outside funeral homes and hospitals around New York. Then came the discovery of 100 bodies decomposing in an unrefrigerated truck at another Brooklyn funeral home. Afterwards, the NYPD came knocking on the door of Cassieri’s business, insisting on inspecting his truck to ensure that it was refrigerated.

Cassieri presses on. He regularly begins work at 5:30 a.m. and doesn’t leave until well after midnight. In one day alone, Cassieri made 11 hospital removals.

“We’re doing our best. There are just not enough hours. We can’t move or prepare bodies fast enough. We’re locked down by cemeteries and crematories. There’s only so much we can do,” says Cassieri, who purchased additional stretchers and a new removal van. He rented a U-Haul truck to make extra removals.

It’s hard not to feel abandoned by the government. “Nobody helped us. FEMA never stepped in, and the city never called and said we could move bodies 24 hours a day from the medical examiner’s,” Cassieri says.

In our business, we, just like the families of the deceased, have relied on the comforting and predictable rituals of funeral services. No more. They have been replaced by chaos and uncertainty. There are no typical days. We adapt as best we can to rules and regulations that seem to change arbitrarily, and often without notice. Sometimes those rules seem borne of fear rather than neccesity.

At the same, we can’t help but feel a special duty as we serve as often lone witnesses at funerals that are unattended.

“Today, my daughter and I live-streamed three graveside services via Tribucast,” says Peter D’Arienzo, Market Director of Dignity Memorial, Long Island. “At two of these services, the rabbi and monsoon rains were the only ones there.” Through technology, D’Arienzo was able to bring in more than 100 guests from Israel, Germany, France, and around the U.S. “Our mission, and why we chose funeral service, is to give families under any conditions, anyway that we can, a chance to say goodbye,” D’Arienzo wrote on Facebook in mid-April.

As the number of deaths mounted, D’Arienzo’s daughter, Sophia, offered to assist. She was a nursing student, home from college. “Sophia was better at it than I was,” he says. She assisted for two weeks. Others had to fill in when D’Arienzo was forced to self-quarantine for two weeks. Dignity Memorial has live streamed over 25 services to ten foreign countries, and 35 states, with over 1,200 links opened during the COVID-19 pandemic.

They kept going even as rain swept through the area. “The most powerful services are when it is just me and the rabbi at the graveside,” D’Arienzo says.

It is a time when nothing seems easy or predictable for any of us charged with attending to the dead. At one of Cassieri’s funerals, elderly family members had rented a limousine to travel to a New Jersey cemetery. When they arrived, the cemetery refused to allow the car inside the gate. Only one person was allowed at the gravesite, Cassieri was told. “We didn’t know that. That was something that changed between us ordering the grave and getting there,” he says. The cemetery eventually relented, but allowed only one family member to get out of the car and stand by the grave. The family was left to decide who that would be.

The rules change almost hour to hour. Thomas Will, a funeral director for 50 years, was told by a cemetery in the Bronx that no more than five people could be in attendance, all of them required to wear masks and rubber gloves. But when he arrived at the cemetery with two cars bringing family members, he was told that the family would have to remain in their cars.

“You mean to tell me the priest is going to do the service and the family is going to be on the road and they can’t exit their vehicles?” he asked the cemetery official.

He went back to the family. “There’s no way that I’m going to sit in the car during my mother’s service,” said one of the daughters. She threatened to call the police. After the priest arrived, he and Will spoke with the foreman. A compromise was reached. The casket was taken out of the hearse and wheeled to the roadside. The family was able to stand outside of their cars as the priest conducted the brief committal service.

At times, New York has had to look elsewhere for help burying its dead. In the early days of the crisis, John Scalia, owner of the John Vincent Scalia Home for Funerals on Staten Island, located three crematories in Pennsylvania. In April, he would be asked to do 90 cremations, many times the normal rate, but the outreach to Pennsylvania made a difference. “We were able to keep people out of the trailers,” he says. Scalia also made it his mission to handle funerals free of charge for indigent COVID-19 victims.

“I think it’s our obligation to take care of these people. We’re in the funeral business,” says Scalia.

I have spent four decades as a funeral director. In that time I thought I’d seen just about every imaginable way of dying. But nothing could have prepared any of us for this. The days have been dark, filled with fear, frustration, and uncertainty, as we’ve had to face our most daunting challenge as funeral directors. Many of us wonder if we have fallen short of the oath we took, when we were licensed, not to violate our obligation to society or to the dignity of our profession. Maybe, as one of my colleagues said, “It takes this to remind us why we do what we do.”

Featured image: Sophia D’Arienzo live streams a funeral service at which Rabbi Ronnie Kehati officiates (Photo Courtesy of Peter D’Arienzo)

Please Stop Calling it “Social Distancing”

I believe in the power of words: they shape how we think, the emotions we feel, the way we act on our world, and how we interact with others.

Given the power of words, I would have thought that our government would have hired linguists, marketing and branding experts, and creative writers when they developed directives for how we should respond to the COVID-19 crisis. But, in my view, it doesn’t appear that they did based on the words chosen to describe the single most impactful directive: “social distancing.”

I find this phrase troubling for two reasons. First, it’s an inaccurate representation of what we are being asked to do. Medical experts aren’t asking us to distance ourselves socially; rather, they are asking us to distance ourselves physically, thus the six feet of separation it wants us to maintain to reduce the chances of spreading COVID-19. The word “social” has nothing to do with maintaining a certain distance from others.

Second, calling this guideline “social” distancing is actually hurting us in ways that are unintended and subtle, yet undeniable. The phrase discourages us from connecting with others at a time when we need to be social (safely, of course) more than ever: communicating, empathizing, caring, supporting, sharing.

As social beings, our need for interactions with others is hard wired into us through eons of evolution. Social contact benefits us psychologically, emotionally, and physically. Social connection makes us feel more comfortable, more relaxed, and safer. Social support has been found to act as an essential buffer against stress.

Is there a more important time for us to stay connected socially than now when, due to the pandemic, we can’t go to work or school, we aren’t supposed to visit family or friends, and have to isolate ourselves in our homes from the outside world?

For many of us, the most meaningful social interactions we have are now mediated through a screen. Thankfully, technology allows us to stay “connected” even during self-quarantine. What a life saver for so many people; imagine if the pandemic had struck pre-internet. Now that is real isolation! Virtual happy hours, coffee klatches, and dating are reasonable facsimiles of social interactions, but they aren’t nearly as satisfying as the real thing. Social connection mediated through a screen is no replacement for real social connection, even if at a distance of six feet.

You may think it’s difficult to socialize with people with the “physical-distancing” directive instructing us to stay apart, but it’s much easier than you think. Every time you leave your home, you have the opportunity to connect with others and allow others to connect with you. You can both give and receive support when we are all feeling isolated and disconnected. At a basic level, connecting helps us feel like we are still a part of something bigger than ourselves when we all can feel like it is us against the world (especially those who live alone).

Here’s what I suggest you do to create social connection and support for ourselves and others during this time of physical distancing. Start with a basic goal: “I’m going to connect with and support people whenever I leave the house.”

When you go for a walk, run, or bike ride, say “hello” or “beautiful day” to everyone you pass (even if they have headphones on. By the way, if you usually wear headphones, try doing without them for the sake of social connection). I do this on my walks with our dog and on my morning runs and everyone always perks up and responds in kind (though some with an initial look of surprise).

When you’re in line outside the grocery store (an all-too-frequent sight these days), don’t just look around or stare at your phone. Instead, use it as an opportunity to strike up a conversation with the person next to you. Start with something as simple as “How are you getting along with all this?” I can assure you that most people will respond with a smile, a breath of relief, and an eagerness to engage.

These days, a big obstacle to connecting with others in spontaneous ways is that just about everyone is wearing a face mask of some sort in public. We can see people’s eyes (though not that well from six feet away), but we can’t see the rest of their faces. We are wired, again through evolution, to read and interpret facial expressions; it helped us decide whether rival tribespeople wanted to have dinner with us or have us for dinner. With face masks on, we don’t know how receptive people will be to connecting, and we worry about being ignored or rebuffed for our efforts. We just don’t know whether the expression under the mask is a scowl (“Not interested”), a smile (“Hello, neighbor”) or a grimace (“I’m feeling so sad today”). But I go under the assumption that we’re all starved for real human contact, even at a distance of six feet, so it’s worth the risk.

During these scary times, our natural reactions are to turn inward, circle our psychological and emotional wagons, and close ourselves off from others to protect ourselves from the invisible, yet potentially deadly, threat of COVID-19. But that is the worst thing to do, so please, do just the opposite. Reach out and connect with those around you. Show others that they are seen, heard, and met by you in this tragic and traumatic once-in-a-lifetime (hopefully) moment. I can assure you that both you and they will be glad you did.

Dr. Jim Taylor is the author of How to Survive & Thrive When Bad Things Happen: Nine Steps to Cultivating an Opportunity Mindset in a Crisis (Rowman & Littlefield, 2019).

Wit’s End: Get Ready for the Worst. Summer. Ever.

Like a mole emerging, blinking, into the sunlight, the nation is poking its snout into the air, and there is cautious talk of some non-home activities resuming.

But make no mistake: This summer is going to be one of the lamer ones on record. Gone are the carefree days of doing whatever the hell you feel like in July and the barely-remembered schoolyard retort: “You’re not the boss of me.” This year, the local July 4th fireworks extravaganza has been cancelled, and your federal, state, and county government is very much the boss of you. A year ago, acting responsibly meant trying not to hit anyone with your car, but by this summer, 6,000 new rules will govern that slice of American life called “leaving the house.”

Major buzzkills in the summer of 2020 may include:

Shopping. Does your niece have an upcoming birthday? Eager to browse the latest nonfiction releases? Bathroom faucet leaking and you need a . . . thingy from the hardware store? STAY IN YOUR CAR, MAGGOT. Don’t even think about physically entering a shop. “2019 called: They want their sense of entitlement back!” It’s 2020, and here’s the rules: If you phone in advance, specifying the exact item you want and your debit card number, a store employee grateful to have a job at all will text you when it’s available for curbside pickup. Please wear a mask and do not breathe on said employee. Sneezing will result in your immediate arrest. Thanks, come again!

Summer camps. All children’s summer and day camps are cancelled. The public pools are closed, so hopefully you have a rich friend with a pool. (Don’t try to befriend people with swimming pools in 2020. It’s too late, you presumptuous peasant.) Any child trying to climb a public play structure in the summer of 2020 will be hosed down by city workers with a mixture of lye and tap water. Public libraries will remain open between the hours of 1:00 and 2:30 p.m. on Tuesdays, allowing up to ten masked children inside at one time. Once in the library, each child will be relegated to an individual Caring Square, a six-by-six-foot area of carpet, because caring for other people means staying away from them, you grubby little vectors. Now scamper back home to your parents, who are beginning to get the hang of heavy day-drinking.

Travel. Cancelled. Persons attempting to cross state lines in the summer of 2020 will be chased back to their abodes by a masked mob brandishing sticks. In the absence of law enforcement, the mob is authorized to take corrective action against citizens attempting a chill road trip to Sedona or Moab. Anyone on a beach is a de facto “beach bum” subject to a loitering citation. From June through August, you’ll stay in your backyard and like it, you human murder hornet.

Family reunions. If your clan insists on getting together this summer, at least have the decency to exclude Grandma. She’s better off confined to her home, a locked-down nursing facility, or a wise old tree that embodies her spirit as in the movie Pocahontas. While the family matriarch shelters in place, relatives can enjoy her ghostly presence with brand-new Holo-Gram technology, enabling 3-D apparitions of Holo-Gramma, Holo-Grampa, and Holo-Old Lady at Church Back When Church was a Thing. Just don’t try sitting on Holo-Gramma’s lap, kids: She’s nothing but light particles in air!

Nights on the town. Remember when “dinner and a movie” was a cliché? Though not very adventurous, it’s what most people did for fun. This summer, though, conversations may go like this:

“I’m planning to bungee-jump off a rock cliff into an 800-foot gorge out of sheer existential boredom.”

“Yeah, I get that. I really do. Good luck!”

“And if I survive, I’m thinking of going out for dinner and a movie.”

“What? Seriously? Have you thought this through?”

“I just miss being around people, you know? And the new Christopher Nolan film will be in theaters in July —”

“Theaters? I wouldn’t be caught dead in a public movie theater. Do they even take your temperature before you enter?”

“No, I don’t think so. But they’re seating people several feet apart —”

“Wow, I guess I had no idea you were so selfish. What if you’re an asymptomatic carrier and strangers die because you’re ‘tired’ of watching feature films at home? ‘Oh, takeout’s not good enough for me! I’m the King! I get whatever I want, watch me bang my scepter and make bad choices that benefit only myself! Bang! Bang!’ Just wow.”

Personal Grooming. With all the waxing salons closed, plan on seeing a lot of hairy legs, back fur, and other unpleasantness this summer. Look for the 1920’s unisex swimsuit to make a comeback: short, one-piece overalls that cover everything from the neck to mid-thigh. It will be for the best.

Going into June, 2020 continues to be a rough year, but there are things even a national shutdown can’t take away. Long, sunny days, burgeoning gardens, and having our immediate family members around 24/7, literally every second of our lives, are some of the things we can look forward to, as well as hiding in the garage per usual.

And don’t forget to run some medical experiments for the greater good. Germany is kicking butt on the global pandemic scorecard, possibly because beer has anti-viral properties. We will be testing that theory at home this summer. Results to follow.

Featured image: Shutterstock

Con Watch: The Coronavirus Brings Increased Danger of Income Tax Identity Theft

Steve Weisman is a lawyer, college professor, author, and one of the country’s leading experts in cybersecurity, identity theft, and scams. See Steve’s other Con Watch articles.

When the CARES Act was passed by Congress at the end of March, many people happily anticipated receiving their much needed payments of as much as $1,200 per person. Few expected that due to a perfect storm of circumstances, not only would some people not receive their CARES Act stimulus payment, but also would also become victims of identity theft.

This is just what happened recently to Jim and Dawn Ackerman of Illinois, who were expecting to receive their $1,200 stimulus checks, but instead learned that their checks had been sent to someone who had stolen their identities, according to CBSN Chicago. Making matters worse, the Ackermans were also victims of income tax identity theft, which occurred when someone filed a phony 2019 federal income tax return in their name before the Ackermans filed theirs. The Ackermans found out about the theft when the IRS notified them that someone had already filed their 2019 federal income tax return, and that they would not be receiving their income tax refund until the matter had been investigated.

Unfortunately, it currently takes the IRS an average of 166 days to complete income tax identity investigations; during the Coronavirus pandemic, it can be expected that this time will lengthen.

Stimulus payments under the CARES Act are usually determined by the information contained on your 2019 federal income tax return or, if you have not filed a 2019 income tax return yet, by your 2018 income tax return. And with the filing deadline extended to July 15, many people have not been in a rush to send in their 2019 returns. According to the IRS, as of April 17 the total income tax returns filed were down by 15.5 percent compared to last year. With the delay, income tax identity thieves will be filing phony 2019 income tax returns in larger numbers this year before their victims file their legitimate returns. This will enable the thieves to also direct the CARES Act stimulus payments of their victims to the criminals’ bank accounts. People who have delayed filing their 2019 income tax returns may be getting a rude awakening.

Things may look even more grim if you filed your return by mail instead of electronically. In April, the IRS announced it was not currently processing paper income tax returns. This leaves identity thieves with a greater opportunity to file an electronic income tax return in your name, which will be processed before your paper income tax return. They can then easily steal your CARES Act payment.

What should you do? If you have already filed your 2019 income tax return electronically and provided your bank account number and bank routing number with your return, you should be fine. If you filed your 2019 income tax return electronically, but didn’t provide the IRS with your bank account information, you can go to the IRS’s Get My Payment tool and provide a bank account to which your CARES Act stimulus check can be sent.

Unfortunately, some people are finding that the Get My Payment tool does not allow them to provide this information. In most instances this is due to security issues with the IRS not being able to verify your Social Security number, address, or other personal information. The IRS updates the Get My Payment tool each day with new information, so you can try to provide your banking information again the next day, but there is no guarantee that you will be successful. In no event should you file a second income tax return with bank account information.

If you have not yet filed your 2019 federal income tax return, you should do so as soon as possible both to prevent income tax and stimulus check identity theft. Filing early is always the best defense against income tax identity theft. It is important to remember that when you do file your 2019 federal income tax return, you should do so electronically because we have no idea when the IRS will start processing paper income tax returns again.

Featured image: Shutterstock

9 Unique Activities to Keep Boredom at Bay During Quarantine

COVID-19 has forced us to remain inside, where it’s all too easy for boredom to take hold. Instead, try one of these unique activities that are perfect during this time of social distancing.

9. Parody Famous Paintings

Who knew that recreating artworks in lockdown would become the hottest social media trend of 2020? https://t.co/F0X9icY2dF pic.twitter.com/RWmtoaW5gb

— Artnet (@artnet) May 4, 2020

You have probably seen this one already, and participating is simple: find a painting online and use items around your house to replicate the outfits, setting, and props within the painting. Since this activity is designed for fun, the details do not have to be exact. Put your own unique spin on the artist’s work. When your painting is complete, take a picture and put it side-by-side with the original so you can share your creativity with others.

8. Find Inanimate Faces

What inanimate object face are you on this the 467th day of lockdown? I think I am in a perpetual state of number 6 pic.twitter.com/alyfOfGrRi

— James (@Shabby_Dad) March 31, 2020

You may have never noticed it, but faces can be spotted amongst many household items. For instance, the pillows on your couch might form eyes, or the cord on your chandelier possibly creates a long nose. This activity taps into your imagination and will send you on a scavenger hunt throughout your entire house. More than likely, you won’t look at any of those objects the same way again.

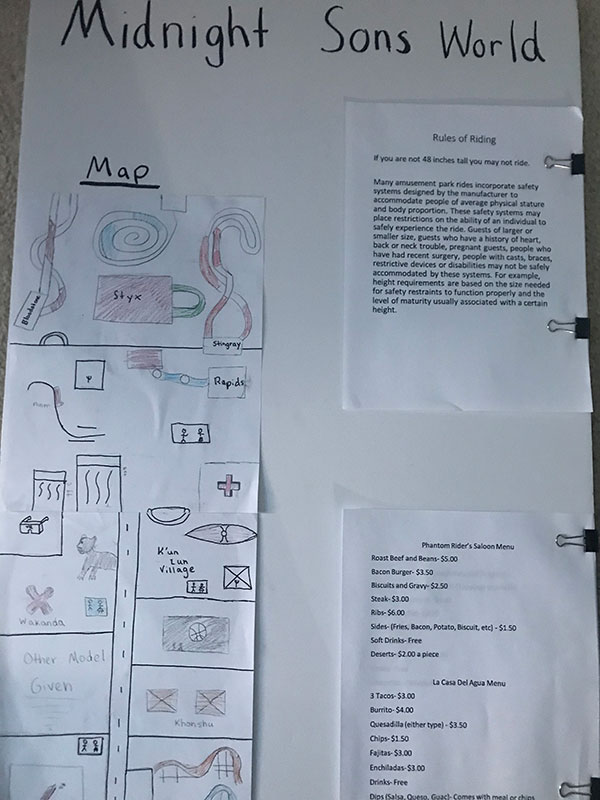

7. Design an Amusement Park

If you are a parent, this activity is a great way to keep your kids occupied, but it’s also fun for adults. Designing an amusement park allows people to see what it would be like to be an Imagineer at Disney theme parks or a Universal Creative team member. In this venture, you’ll come up with the name of an all new theme park, as well as its location, attractions, rides, and restaurants. What makes your park unique? What characters can you meet throughout? Does the park have a gift shop? How much does your park cost? There are endless ways to execute this project. Here’s one lesson plan to get you started.

6. Play Balloon Spikeball

Spikeball is an exciting outdoor game where players bounce a medium-sized ball off a net in an attempt to score points against other players. But Spikeball can be adapted to work indoors as well; just replace the ball with a balloon. One tip: bring a few extra balloons, in case somebody gets carried away.

5. Dress Up with Your Family

Best Family Costumes😂 pic.twitter.com/hUoCTYkOTp

— ZuZuQ🌹9️⃣ (@ZuZuQ5) May 4, 2020

People — sometimes entire families — are dressing up each day in accordance with a daily theme, sometimes oriented around a holiday, a color, a movie — any topic will do. Another adaptation is where each person chooses what another family member wears to dinner. Just put the names of everyone in a cup and draw to see who designs whose outfit. Like other items on this list, this activity is open to interpretation and can be changed to fit your group’s unique ideas and interests.

4. Go on a Scavenger Hunt

Scavenger hunts are a classic. Find some unique or unusual items, then hide them around the interior and possibly the exterior of your house. See who can find the most items. Put a prize on the line, or just play for fun. It is like an Easter egg hunt, but with more variety. Check out these ideas for adults and children.

3. Create a Harry Potter Escape Room

Use your knowledge of the Harry Potter series to create an immersive experience for your friends or family, whether in an escape room format (find and solve clues to escape the room) or an Amazing Race format (go to different locations throughout your home and complete challenges, getting clues in order to reach the finish line). Either way, incorporate different things from the books, like the magical creatures, Deathly Hallows, Hogwarts classes, or whatever else you desire. This example from Peters Township Public Library can provide inspiration. This same activity can also be completed with a plethora of other books and movies.

2. Try Your Hand at Trivia

Pick a collection of categories and design the questions and answer choices to go along with it. There are multiple ways to do this. Kahoot, Quizziz, and Gimkit are great for creating trivia games. You can also draw a Jeopardy board or pull random questions out of a hat. You can even set up a video conference to play with socially distanced friends and relatives.

1. Film “A Day in the Life” Videos

With so many entertaining options for quarantine, you need a way to remember them. Film yourself and those around you participating in their quarantine activities. Are your parents cooking a new dish? Film it. Going on a scavenger hunt? Film it. Building a puzzle? Film it, but maybe time lapse is better for that one. You can edit the videos together and have your own documentary to commemorate quarantine.

Featured image: Shutterstock.

5 Life-Hacks During Shelter-in-Place

The COVID-19 crisis is unprecedented in its impact on all of us. It has put the physical and financial lives of billions of people around the world at risk, not only in the short run, but, in all likelihood, for many years to come. The pandemic is truly a once-in-a-lifetime (hopefully) experience. Though the crisis has many implications that affect all of our lives, when it comes to day-to-day activities, the word that keeps coming to my mind is “disruption.” The unfortunate reality of COVID-19 is that it has thrown a huge monkey wrench in the machinery of our lives What had been predictable is now uncertain. What had been within our control is no longer the case. What had been habit and routine is no more. In other words, our daily lives have been turned upside down.

But that disruption can be a good thing. As I describe in my book, Change Your Life-inertia: Break Free from Your Past and Take Control of the Forces that Propel Your Life Trajectory, our lives can feel like an asteroid hurtling uncontrollably through space. In a sense, due to our upbringings and ongoing life experiences, our lives can develop an inertia that doesn’t encourage change even if the path we are on isn’t what is bringing us meaning, satisfaction, or happiness. The challenge is that, for anyone who is familiar with Newton’s Laws of Motion, it can be very difficult to change course because inertia keeps our lives on their present trajectory.

The COVID-19 crisis has certainly exerted a powerful force on our lives that requires us to alter the path we are on, at least temporarily. Most of that force isn’t positive or healthy because it lies outside of our control. At the same time, we don’t have to be asteroids hurtling through life. Instead, we can be Captains of “Starship You” in which we take command of our lives and use this massive disruption as a positive force to make beneficial changes that will help us in the short term and in the long run.

Certainly, the most immediate and noticeable disruption in our lives has been the “shelter-in-place” order that has been authorized by most states in the U.S. and in most countries around the world. This directive has required us to stay in our homes together either alone (if we don’t have roommates, partners, or family) or with our families. Not being able to go to work, attend school, socialize, run errands, or travel are all new and disconcerting disruptions to the rhythm and flow of our lives.

At the same time, these unsettling changes present us with a surprising opportunity to use this disruption to reflect on and take action to make positive and healthy changes. The goal of these changes is to improve how we deal with the stress and uncertainty of the pandemic in the near term and to create a positive and healthy new direction in our lives in the future.

With that objective in mind, here are five “life hacks” that you can do to improve the quality of your life now.

1. Time

Time is our most precious resource because it’s nonrenewable. We want to take advantage of every moment we have. Thanks to the shelter-in-place order limiting commuting, errands, or after-school activities, we now have several extra hours each day to use as we wish. What a wonderful opportunity to be intentional in how we spend those hours.

Take a look at your week and identify specifically what new free time you have. Then ask yourself how you would like to spend it. It might be with your partner or family. It could involve exercise or returning to a neglected hobby. You could devote this time to a new avocation such as learning to cook, taking up a musical instrument, or registering for an online course you’re interested in. Your options are nearly endless, and whatever you choose should pass a simple litmus test: “Am I maximizing the value of this precious time that is available to me?”

2. Family

As a married parent of a teen and a tween, I can attest to the fact that it’s easy to get caught up in the busyness of family life and lose touch with our spouses and children. Work, school, extracurricular activities, homework, and social life all exert a gravitational pull away from the people who are most important to us. Shelter-in-place gives us the chance to spend more time — not just “quality time” — to connect with and strengthen our relationships with our family.

Dinners together every night, walks and bike rides in your neighborhood, weekend outings (close to home and maintaining social distancing from others, of course), games, movies, and just plain old conversation are just a few ways in which you can really connect with the people you love the most.

Admittedly, being together almost 24/7 can also have its challenges as the constant contact can cause everyone to get on each other’s nerves. This tension can also be an opportunity to practice kindness, empathy, and patience with those who deserve it the most.

3. Declutter

One of the most ubiquitous observations I’ve made while walking our dog in our neighborhood since the shelter-in-place order took effect has been the daily piles of junk on the sidewalk ready to be disposed of by our local garbage collectors. With so much free time, everyone seems to have gotten the “declutter” bug. I’m a huge believer in simplifying our lives by getting rid of the junk that we Americans love to accumulate in our closets, storage sheds, and garages. (And to think that garages used to be for cars!)

Without realizing it, clutter can have a big impact on us psychologically and emotionally. As we fill our lives up with stuff that we no longer use or need, clutter can create a claustrophobia that we’re not even aware of. We can feel an undefined closing in around us, a sense of feeling overwhelmed and trapped. Decluttering your space can also declutter your mind, freeing you of unnecessary “mental junk” that encroaches on your thinking and emotions.

The question I’m often asked is: “How do I know what to throw out?” It’s pretty simple; if you haven’t used it or noticed it in the last six months, say goodbye to it. And there is social value to decluttering as well. As the saying goes, “One man’s trash is another man’s treasure,” so when you give your stuff away to a charity, such as Goodwill or Salvation Army, those old clothes, games, and toys are going to people who are in need and would value what you no longer do.

4. Exercise

Those extra hours in the day that I mentioned above can be well used by committing to an exercise regimen.

Admittedly, there are fewer options for exercise with the shelter-in-place order in effect. No swimming pools for laps and no health clubs, gyms, or other fitness-related facilities for weight training, spinning, yoga, dance, or other exercise activities.

You can walk, run, or bike outside (while following the social-distancing guidelines, of course), acquire an indoor bike trainer, or purchase some dumbbells, exercise balls, stretch cords, or other exercise equipment for your own “gym” in your house. Some gyms are letting members borrow exercise equipment for home use. There is now a booming online exercise business with tens of thousands of videos offering a plethora of exercise programs that are fun and motivating that you can follow from the safety of your own home.

5. Change Bad Habits

This disruption of your daily routine offers you a unique opportunity to break unhealthy habits that were too difficult to overcome while you were entrenched in your life before the COVID-19 crisis. Your eating habits are one such area in which you are forced to change. If you had a habit of stopping by that donut shop on the way to work, you no longer can. If you got that latte at Starbucks every day at lunch, sorry. If you ate out more often than not, game over (though, in theory, you could do take-out).

Here’s a good exercise for you to engage in to see which bad habits you can break while in “lockdown.”

- Identify one or two habits you wish you didn’t have (e.g., snacking on junk food whenever you take a break at work).

- Clarify what is bad about them and why you want to break the habit (e.g., causes you to overeat and gain weight).

- Specify a new habit with which you can replace the old habit (e.g., instead of eating when you take a break while working at home, take a walk around the block).

- Create an enjoyable environment for your new habit (e.g., listen to music or podcasts or talk to friends by phone during your walk).

- Accept that you might fall off the wagon periodically, so just recommit to the new habit and get back on the wagon (e.g., if, in a moment of weakness, you bought some potato chips at the store, finish them and resist the urge the next time you are grocery shopping).

- Seek support for your new habit (e.g., if you have a spouse or roommate working from home as well, ask them to help you by not buying snacks themselves and joining you for your walks).

- Choose a reward for staying committed (e.g., treat yourself to a nice take-out dinner each week).

There is no way that we can completely turn the COVID-19 crisis into a thoroughly positive experience. At the same time, to allow it to be totally negative adds insult (e.g., really bums you out) to the injury that’s already being inflicted on us (e.g., financial, social). Instead, see the pandemic as an opportunity to exert positive forces on your life-inertia and make healthy changes. You garner several important benefits from taking this approach to the crisis. First, you’ll feel a lot better psychologically and emotionally during a time that is a natural downer because you are using your time and energy in a constructive way. Second, your experience of the crisis will be much more positive and uplifting. Third, the pandemic will go by faster because you’re focused on more positive things. And, lastly, when the COVID-19 crisis finally passes, you can take the new changes and enter the “real world” happier and better positioned to enjoy your life to the fullest.

Want to learn more about how to respond to the COVID-19 crisis in healthy and constructive ways? Read Dr. Jim Taylor’s new book, How to Survive and Thrive When Bad Things Happen: 9 Steps to Cultivating an Opportunity Mindset in a Crisis, or listen to his podcast, Crisis to Opportunity (or find it on Stitcher, Spotify, iTunes, or Google).

Featured image: Shutterstock

How Social Distancing Can Help Us Rethink Our Gatherings

Gatherings around the world are cancelled or postponed: Concerts, conferences, religious services, birthday parties, yoga classes, the Olympics, funerals. Almost all instances of people in proximity to one another have suddenly evaporated in the U.S. as many of us have been isolating in our homes.

While the COVID-19 pandemic has altered daily life for most everyone, Priya Parker thinks it has created an opportunity for us to reexamine the ways we connect with one another.

Parker is a trained conflict resolution facilitator who started using a process called “sustained dialogue” at University of Virginia to facilitate meaningful conversations and connections across racial and ethnic barriers. As a biracial woman, she noticed a lack of understanding around race on campus, and she decided to do something about it.

In 2018, Parker published The Art of Gathering, a book that calls on us to reconsider the gatherings we plan and attend, from celebrations to meetings to mass events to dinner parties. Parker’s book offers a new way of determining how we should shape these gatherings into meaningful experiences instead of routine events. She writes that “We spend our lives gathering … and we spend much of that time in uninspiring, underwhelming moments that fail to capture us, change us in any way, or connect us to one another.” Parker believes that we can change this, though, even — and maybe especially — in a time of global crisis.

Her new podcast, Together Apart, produced with The New York Times, tells the stories of people navigating our new reality in their own attempts to gather safely and .

In our interview with her, Parker shared her philosophy of getting people together, socially distanced or otherwise.

SEP: You talk in your book about our “ritualized gatherings” and how they’ve been repeated so much over time that we’re attached to the forms of our gatherings even after they no longer reflect our values. What are we doing wrong when we gather?

Priya Parker: We skip over asking what the purpose is. So, we skip too quickly to form. If we’re hosting a baby shower, we assume it has to look a certain way and skip to buying or making the baby games. I wrote about the New York Times “Page One Meeting” in the book, which continued for more than 70 years even after it no longer made sense to have the biggest meeting of the day focusing on what goes on page one, since they now had this thing called the home page. Whether it’s a baby shower or an editor’s meeting, the biggest mistake that we make when we gather is to assume that the purpose is obvious.

SEP: To zero in on the purpose of gatherings, you suggest finding a “disputable purpose” and even excluding people if necessary, in the right way. A lot of us are rule-averse and want to at least appear laid back when we’re planning gatherings, so how do you think we can start to embrace rules like this?

Parker: I would differentiate between principles and rules. I think something like “know why you’re gathering” isn’t a rule; it’s a principle. It’s not controlling or uptight to be asking “why are we doing this?” It’s intentional.

But I do, in the book, write about pop-up rules. Something like practicing generous authority. Something we tend to do in our gatherings is “underhost.” In wanting to not seem too controlling or bossy, we kind of do nothing. This is an argument to say that if you’re interested in creating transformative, memorable gatherings, the way to do that is to have a specific purpose and to create a sequence or structure — that can actually be delightful and fun.

If the purpose of a baby shower is to help a couple figure out how they want to parent when they’ve never seen a model for that in either of their families before, having a baby shower with all women and pinning the diaper on the baby is not going to help you fulfill that purpose. Gathering is a form of power and it’s also the way we spend our time. I’m not so much an advocate of rules so much as I am an advocate of not wasting people’s time.

SEP: Let’s say you’re at a terrible gathering. You know it’s terrible, and everyone else does too, but you’re not the host. Is there anything you can do as a non-host to make a gathering better?

Parker: I called this book The Art of Gathering and not The Art of Hosting, in part, because I think guests have a lot of power. I know of this retirement party that happened pre-COVID, and the team of a department was invited to a retirement lunch, and everybody came and sat down and they were chatting. The person who sent out the invitations was planning to bring out a cake and a plaque at the end, but there were like two hours before that, so everyone was just kind of waiting around while nothing happened and it was a little embarrassing for the person being honored. Then, one of the guests stood up and clinked their glass and started a round of toasts and stories. It was a risk, right? But people went along with it. It gave structure, and completely transformed the event. Through their intervention, that guest transformed something that was mundane into something that was meaningful.

Sometimes it isn’t obvious who the host is, like if you’re at a conference or something and you’ve spontaneously come together with whoever you’ve bumped into. You can intervene and say, “I’m here because I’m new to the industry. Would you guys be up for a conversation?” and go around answering an interesting question. You have a lot of power as a guest to shape an outcome. Part of it is saying “there is a beautiful conversation that could happen here. How do we have it?”

SEP: I think it’s a little more common these days to come across the idea of introvertedness or social anxiety, and some people say they don’t like to be in gatherings or that they don’t like to be around strangers. But you say in your book that “everyone has the ability to gather well.” Does that run counter to the idea of introvertedness?

Parker: One of the things I found interesting writing this was that I interviewed over 100 people for this book who people described as transformative gatherers — in all different fields, a rabbi, a choir conductor, a hockey coach, a photographer — and many of them identified as introverts or sufferers of social anxiety. One of the things I found, at least anecdotally, is that often introverts — people who don’t like to go to gatherings — are some of the best gatherers. This is because they’re creating the gatherings they wish existed.

When you’re designing experiences for other people, I think it’s almost dangerous to rely on a very charismatic personality to lift the group and carry it through something. When you create thoughtful structure, you don’t actually have to do very much once people arrive. I actually think that often when people don’t like going to gatherings, they’re on to something. They don’t like them when they’re really awkward and they aren’t guided with care. They don’t like gatherings where you have to keep introducing yourself or try to prove your worth. It’s exhausting. But there is another way to do this, and, in my experience, introverts and others who are on the outside of communities are really amazing, thoughtful gatherers.

SEP: When it comes to family and friends with really polarizing politics (I think everyone thinks about this around Thanksgiving for some reason), a lot of strategies go around for gathering people like this and keeping conflict at bay. How would you approach gathering people where politics differ and maybe even values differ as well?

Parker: I think first, again, is know the purpose. Is the purpose to engage in politics? Or to have a good time? If you’re trying to interstitch a community and they’re divided on politics, as a conflict resolution facilitator, one of the things you know is that there are different tools for different conflicts. It may make sense to avoid conversation as a centerpiece of your gathering. It may make sense to do it in a sports league or volunteer together. There are a lot of ways to build relationships, and things that allow people to see different sides of each other are going to help to build that community.

When you’re bringing together people who are different, don’t try to make them the same; try to complicate each side. Krista Tippett said “We assume a monolith of the other that we know not to be true of our own side.” So we think “all evangelical Christians … ” or “all white women …” or “all Muslims … ” whereas we know that there’s so much difference even within our own families.

If you’re going to go for it, my suggestion is to ground a conversation around stories, not opinions. Or, don’t focus on conversation and find a meaningful activity that allows people to show different sides of themselves. People could think, oh wow, he is just as competitive as I am, or, she’s also superstitious. We all have different sides to ourselves, so part of loosening that knot isn’t to focus on stamping out the differences but to bring out the complications of each side because they have something in common.

SEP: I find it ironic that you’re book about gathering has just come out in paperback while we’re all social distancing.

Parker: It is an ironic time to deeply understand gatherings when the world is ungathering.

SEP: But you do have this podcast called Together Apart, so I want to know some innovative or inspirational ways you’ve seen people connecting during this pandemic.

Parker: People are finding really beautiful ways to gather even with social distancing. In this week’s episode, which was on birthdays, an aunt and her nephew organized a birthday party in a parking lot for all of the neighbors and asked them to park their cars in a circle and blare pop music and honk as the birthday boy was going to drive through. It was totally amazing to have a release of joy when people are cooped up in their houses, but in a safe way. One interesting thing I’ve been getting a lot of notes on is people living in neighborhoods all over the country who don’t know their neighbors, and all of the sudden, Facebook neighbor groups are popping up saying, “drinks on the lawn, 12 feet apart, 5 p.m.”

One powerful thing we’ve been seeing online is people whose gathering is unique to this time and wouldn’t make much sense in other times. D-Nice, this D.J. in Miami, started spinning sets three weeks ago, and some of his dance parties are 100,000 people. Michelle Obama stopped by, Bernie Sanders, Mark Zuckerberg stopped by, but it was literally open to everybody. It was a strange combination, that I think is difficult in in-person gatherings, of elite and deeply democratic while allowing these psychological V.I.P.s through the door. It reminded me of a quote from Studio 54 when Andy Warhol was criticized for the red rope, and he said “It’s a dictatorship at the door so that it can be a democracy on the dancefloor.” I think D-Nice is this fascinating example of being a democracy at the door and a democracy on the dancefloor.

There are virtual choirs, collective spin classes and knitting classes, Alcoholics Anonymous, happy hours, and everything in between. And I think families are trying to figure out how we can be together apart in a way that’s safe but still specifically marks a moment in our lives.

SEP: Do you think this is a good time to reconnect with old friends?

Parker: Absolutely. This is a massive, generational, global interruption, and it’s a painful one. It makes us pause and think, who do I love? What have I not been doing when I was overbusy? Beyond the question of reconnecting with old friends, it’s really a good time to reconnect with how you want to live. Part of that is who you want to be part of that life.

SEP: What do you hope people take away from your book?

Parker: My deepest hope is that people pause, at work or home or in the public square, and think more intentionally about how we do things together, and then have the courage and the permission to go invent that new way of being.

Featured image: Shutterstock

Your Health Checkup: More COVID-19 Straight Talk

“Your Health Checkup” is our online column by Dr. Douglas Zipes, an internationally acclaimed cardiologist, professor, author, inventor, and authority on pacing and electrophysiology. Dr. Zipes is also a contributor to The Saturday Evening Post print magazine. Subscribe to receive thoughtful articles, new fiction, health and wellness advice, and gems from our archive.

Order Dr. Zipes’ new book, Bear’s Promise, and check out his website www.dougzipes.us.

In my last column I presented COVID-19 information based on credible science that cut through the “fake news” offered largely from politicians. The enthusiastic reader response convinced me to write a second column with the same goal.

1. Six feet of separation may not be enough

Six feet separation, especially without facial covering, may be insufficient to prevent infection by someone with COVID-19. Before the virus invades the lungs, it replicates in the throat and can be contained in droplets from a cough that can travel 16 feet, and from a sneeze traveling 26 feet.

Heavy droplets fall to the ground due to gravity, but smaller particles that break up from the cough or sneeze can become aerosolized and hang in the air for many minutes. Even more importantly, these aerosolized droplets can form from simple breathing or speaking and can remain suspended in the air to drift with air currents and pose an inhalation threat at considerable distances, particularly in enclosed places. It is possible the droplets may drift around you if you are moving and create air currents.

Scientists in a recent study found that when a person said the words, “stay healthy,” in a normal voice, numerous tiny droplets were emitted from the mouth and increased in amount with the loudness of the voice. A damp washcloth held over the mouth when the same phrase was uttered significantly decreased the amount of aerosol. The scientists did not measure virus particles in the droplets.

I would suggest separating as far away as possible from others not in your household, staying out of closed, small rooms in public places as much as you can, and wearing a facial mask when out.

2. Hospital admissions for other diseases like heart attacks, strokes, and cancers have fallen

Perhaps due to fears of contracting COVID-19 infections, or fears of utilizing a room or health care time better saved for COVID-19 patients, reports suggest a recent drop in admission of patients with serious diseases, including about a 40 percent decrease in heart attack admissions alone in the U.S. Such delay of essential health care for serious diseases is causing a health care crisis of its own. Most heart attacks and strokes are caused by reduced blood flow to a region of the heart or brain that kills vital tissue in those organs. Prompt restoration of blood flow is the most important approach to preventing tissue death and minimizing the size of the heart attack or stroke. Speed is essential; the faster the patient is treated increases the amount of tissue that can be saved, which increases the chance for survival and decreases the risk of complications.

Patients should call 911 immediately if they experience symptoms of a heart attack, stroke, cancer or any other serious illness, despite this pandemic. It is also important in these stressful times to maintain a healthy lifestyle with regard to diet, exercise, taking medicines, and all the important issues addressed in previous columns (see my earlier columns on 4 Suggestions for Better Health, 2 Simple Things that Might Save Your Life, and Blood Pressure, Kitchen Germs, and Antibiotic Resistance). Remember, COVID-19 doesn’t just affect lungs. It can also impact heart, liver, GI tract, blood, kidneys, eyes, brain, taste, and smell.

3. Possible good news

Many new drugs are being tested against the COVID-19 virus, and, while no proven therapy yet exits, there may be some preliminary good news. A drug called remdesivir, used to treat Ebola, has shown important anti-coronavirus action in test tubes and in early clinical studies. At the University of Chicago, 125 people with COVID-19 were treated with daily infusions of remdesivir. Preliminary observations indicated rapid recoveries in fever and respiratory symptoms, with nearly all patients discharged in less than a week; two patients died.

In another study of patients hospitalized for severe COVID-19 infection who were treated with remdesivir, clinical improvement was observed in 36 of 53 patients (68 percent); seven patients died.

Randomized, controlled trials of chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine, anti-malarial drugs, are also under investigation. So far, the results have been mixed and inconclusive. A potential side effect of combining chloroquine or hydroxychloroquine with the antibiotic azithromycin, as has been suggested, is a harmful effect on the electrical system of the heart that can lead to heart rhythm problems and even sudden death (https://www.crediblemeds.org), as found in a recent trial of 81 Brazilian patients.

Additional randomized, placebo-controlled trials will be critical to determine the true benefits of new drugs in COVID-19 populations. There are over 1500 studies planned or in process.

Finally, convalescent plasma containing antibodies from patients who have recovered from COVID-19 infections has been helpful in a small number of patients, though the efficacy of COVID-19 antibodies may not be as great as in other diseases.

Ultimately, we need a vaccine to protect us from getting infected in the first place. That may be more difficult to develop than we first thought because antibodies may not be that effective in clearing the virus from the body. Also, the virus can mutate, reducing the vaccine’s effectiveness. Nevertheless, vaccine development is the direction medicine has to take if we’re ever going to be safe from COVID-19.

Featured image: Shutterstock

Wit’s End: Stuck at Home? There’s a Meme for That

Weeks ago, when everyone in my office started working remotely, we began sharing funny memes to keep in touch.

The thinking was that, as lockdown orders swept the nation and anxieties mounted, if a colleague still had the presence of mind to send an amusing, work-appropriate meme, they could probably be trusted with other things.

If, on the other hand, someone “went dark” and texted nothing to the group, or sent a blurry photo of a crying face, or a series of beer emojis, or the phrase “I can’t even,” it was a sign to subtly direct the workflow elsewhere.

Swapping visual jokes about shared experiences – toilet paper shortages, Zoom meetings, children cooped up at home all day – has been good for group morale when we’re miles apart. But a decade ago, few of us would have known what a meme was.

Richard Dawkins, an evolutionary biologist, coined the word “meme” in his 1976 book The Selfish Gene. Just as a gene transmits genetic information, a meme transmits cultural information. Examples of memes were “tunes, ideas, or catch-phrases” that “[leapt] from brain to brain,” wrote Dawkins. A decade later, writer Eloise L. Kinney described memes as “simply put, ideas that catch on.”

In 2020, when people say “meme,” they usually mean a joke, fad, or image that’s circulating on the Internet. According to a source in my household, today’s fifth graders traffic heavily in memes, sharing cat jokes on social media and learning dance moves from TikTok videos.

“The dance that’s trending all over America,” my 11-year-old daughter informed me, “is called The Renegade, where you just fling your arms around meaninglessly.”

That’s a meme.

Now that the nation’s office workers are stuck at home, many of us have seized on memes as a popular art form. Years from now, novels will be written, movies filmed, and music composed about this period in history, but no one can wait for these thoughtful, intricate forms of expression. We need to see our bizarre predicament mirrored back to us, right now, in the form of a doctored photo of Julie Andrews’ Maria from “The Sound of Music” being dragged away from the Bavarian Alps by police officers, with the tagline: “The Hills are closed.”

Indeed, they are. The clever mash-up of a classic reference and a current problem is what makes some memes so appealing. They’re free to all and have a universal feel. In our celebrity-obsessed culture, meme-makers ply their craft in anonymity: Everything that made me laugh today was conceived and executed by some faceless nerd, playing a dangerous game with the law of copyright.

During the last several weeks, we’ve seen “Brady Bunch” memes and memes of Jack Nicholson in “The Shining,” dressed in a bathrobe and leering insanely with a drink in his hand. (The joke was that his character, Jack, seemed to be coping pretty well with isolation.)

We’ve shared memes of dogs hiding after the umpteenth daily walk, and obese cats sprawled on the couch, embodying our “weekend plans.”

There have been “Star Wars” memes (Obi-Wan attempting to remote-teach Luke Skywalker about The Force), and memes based on old sitcoms like “The Office” and “The Golden Girls.”

Then there are random, semi-disturbing images, like the meme I found of a goose with human arms, gesticulating wildly. The tagline quoted the 1985 Aretha Franklin radio hit: “Who’s Zoomin’ Who?”

“Do you do any actual work?” asked my husband at some point.

“Yes! We get a lot done. These funny memes are helping us stay motivated!”

He shrugged and shuffled back to the bedroom where his work laptop was, along with the pretzels, chips, and salsa he now ate in there. We had relaxed the household rules, everyone coping in their own ways. My new shutdown habits were sending memes and taking naps, which suddenly seemed like a pleasant way to live. Why hadn’t we been doing these things all along?

Of course, most things about the national situation weren’t funny. Like everyone else, we were concerned for the sick and elderly, people whose jobs put them at risk, and the millions now out of work. We were helpless to solve these big problems, however, and succumbing to worry and depression would help exactly no one. So it seemed okay – even necessary, perhaps – to find things funny. If America lost its creative, irreverent sense of humor, the terrorist had won.

Hence, The Atlantic’s recent essay: “Yes, Make Coronavirus Jokes.” Writer Tom McTague observed that “as the world hunkers down, . . . there’s been a mass outpouring of gags, memes, funny videos, and general silliness. We might be scared, but we seem determined to carry on laughing.” Shared humor creates feelings of bondedness, acceptance, and community, McTague reported. “If we’re all finding this experience of being forced to stay home funny, it’s reassuring, a form of collective therapy.”

Similarly, Esquire published an essay earlier this month called: “Coronavirus Memes Brought My Dad and I Closer Together.” Sheltering in place far from his aging parents, writer James Stout praised silly memes (like “high-quality clips of people falling over”) for connecting him and his father in laughter on a daily basis. “Maybe it’s a bit of a stretch to think that dogs driving lawnmowers will bring us all together after this is over, but it is genuinely heartwarming to see the internet being used to spread joy,” he wrote.

Now if you’ll excuse me, I’m off to Google “cutting own hair bad idea memes 2020.”

Featured image: Shutterstock

A Letter from Sacramento, Where Fear Blooms as Flowers Grow

Our front garden hit peak bloom just as the COVID-19 death toll passed 200 in California. As usual, the California golden poppies seized control of the gravel borders along the driveway and, in a brazen move, advanced this spring into the chipped bark meant to provide walking space around the raised planter boxes. Now the last daffodils poke their heads out among the crimson flutter of the Greek poppies. The irises are flaunting wings and beards, each according to its wont, in random pairings around the yard. And the redbud is in full blossom on Mount Robin—the formal name for the mound of native plants my wife has let loose to the south of the front walk.

The garden has staged memorable spring performances before, though always to small audiences. We live four miles south of the State Capitol, well off the beaten path, on an eyebrow street just six houses long, connecting nothing to nowhere. Our hilly neighborhood of ranch houses was built without sidewalks in the early 1950s, when California planners were certain that walking was obsolete.

Weeks ago, back in normal times, only a few familiar souls would wander by. The dog walkers from the next block over. The slight blond teen walking bent, like a peasant woman carrying a bundle of firewood, under a backpack full of textbooks. The mother going to and from the nearby elementary school to retrieve her kids.