“The Benefit of the Doubt” by Jack London

Jack London’s short stories in the Post concerned adventurers, criminals, workingmen, society folks, and — sometimes — wild animals. In “The Benefit of the Doubt,” from 1910, a class-concerned sociologist gets a hands-on lesson in justice and corruption when he ducks in to the wrong dive bar in his hometown.

Published on November 12, 1910

With a current magazine under his arm, Carter Watson strolled slowly along, gazing about him curiously. Twenty years had elapsed since he had been on this particular street, and the changes were great and stupefying. This Western city of three hundred thousand souls had contained but thirty thousand when, as a boy, he had been wont to ramble along its streets. In those days the street he was now on had been a quiet residence street in the respectable working-class quarter. On this late afternoon he found that it had been submerged by a vast and vicious tenderloin. Chinese and Japanese shops and dens abounded, all confusedly intermingled with low bars and boozing kens. This quiet street of his youth had become the toughest quarter of the city.

He looked at his watch. It was half past five. It was the slack time of the day in such a region, as he well knew, yet he was curious to see. In all his score of years of wandering and studying social conditions over the world he had carried with him the memory of his old town as a sweet and wholesome place. The metamorphosis he now beheld was startling. He certainly must continue his stroll and glimpse the infamy to which his town had descended.

Another thing: Carter Watson had a keen social and civic consciousness. Independently wealthy, he had been loath to dissipate his energies in the pink teas and freak dinners of society, while actresses, race-horses and kindred diversions had left him cold. He had the ethical bee in his bonnet and was a reformer of no mean pretension, though his work had been mainly in the line of contributions to the heavier reviews and quarterlies and to the publication over his name of brightly, cleverly written books on the working classes and the alum-dwellers. Among the twenty-seven to his credit occurred titles such as, If Christ Came to New Orleans, The Worked-Out Worker, Tenement Reform in Berlin, The Rural Slums of England, The People of the East Side, Reform Versus Revolution, The University Settlement as a Hotbed of Radicalism and The Cave Man of Civilization.

But Carter Watson was neither morbid nor fanatic. He did not lose his head over the horrors he encountered, studied and exposed. No hare-brained enthusiasm branded him. His humor saved him, as did his wide experience and his conservative, philosophic temperament. Nor did he have any patience with lightning-change reform theories. As he saw it, society would grow better only through the painfully slow and arduously painful processes of evolution. There were no short cuts, no sudden regenerations. The betterment of mankind must be worked out in agony and misery just as all past social betterments had been worked out.

But on this late summer afternoon Carter Watson was curious. As he moved along he paused before a gaudy drinking place. The sign above read, The Vendome. There were two entrances. One evidently led to the bar. This he did not explore. The other was a narrow hallway. Passing through this he found himself in a huge room filled with chair-encircled tables and quite deserted. In the dim light he discerned a piano in the distance. Making a mental note that he would come back some time and study the class of persons that must sit and drink at those multitudinous tables, he proceeded to circumnavigate the room.

Now at the rear a short hallway led off to a small kitchen, and here, at a table, alone, sat Patsy Horan, proprietor of The Vendome, consuming a hasty supper ere the evening rush of business. Also, Patsy Horan was angry with the world. He had got out on the wrong side of bed that morning, and nothing had gone right all day. Had his barkeepers been asked, they would have described his mental condition as a grouch. But Carter Watson did not know this. As he passed the little hallway Patsy Horan’s sullen eyes lighted on the magazine he carried under his arm. Patsy did not know Carter Watson, nor did he know that what he carried under his arm was a magazine. Patsy, out of the depths of his grouch, decided that this stranger was one of those pests who marred and scarred the walls of his back rooms by tacking up or pasting up advertisements. The color on the front cover of the magazine convinced him that it was such an advertisement. Thus the trouble began. Knife and fork in hand, Patsy leaped for Carter Watson.

“Out wid yeh!” Patsy bellowed. “I know yer game!”

Carter Watson was startled. The man had come upon him like the eruption of a jack-in-the-box.

“Adefacin’ me walls,” cried Patsy, at the same time emitting a string of vivid and vile, rather than virile, epithets of opprobrium.

“If I have given any offense, I did not mean to — ”

“But that was as far as the visitor got. Patsy interrupted.

“Get out wid yeh; yeh talk too much wid yer mouth!” quoth Patsy, emphasizing his remarks with flourishes of the knife and fork.

Carter Watson caught a quick vision of that eating fork inserted uncomfortably between his ribs, knew that it would be rash to talk further with his mouth, and promptly turned to go. The sight of his meekly retreating back must have further enraged Patsy Horan, for that worthy, dropping the table implements, sprang upon him.

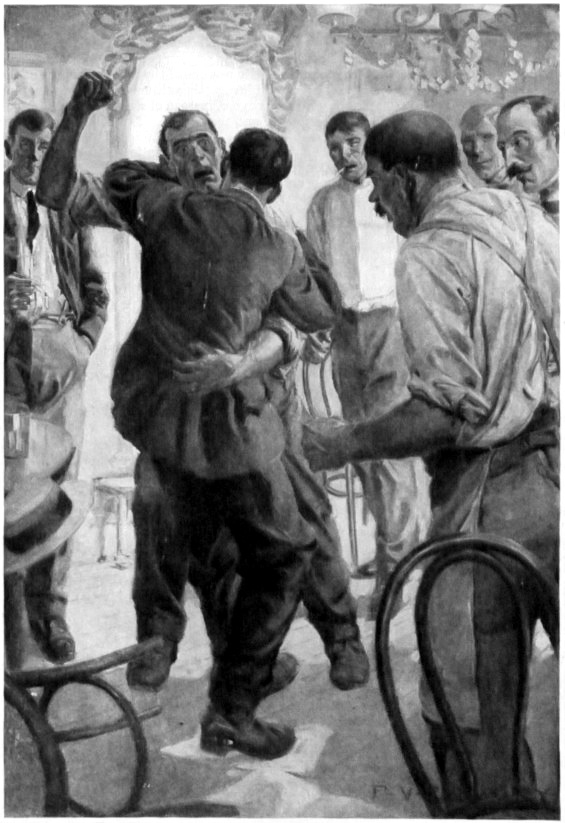

Patsy weighed one hundred and eighty pounds. So did Watson. In this they were equal. But Patsy was a rushing, rough-and-tumble saloon fighter, while Watson was a boxer. In this the latter had the advantage, for Patsy came in wide open, swinging his right in a perilous sweep. All Watson had to do was to straight-left him and escape. But Watson had another advantage. His boxing and his experience in the slums and ghettos of the world had taught him restraint.

He pivoted on his feet and, instead of striking, ducked the other’s swinging blow and went into a clinch. But Patsy, charging like a bull, had the momentum of his rush, while Watson, whirling to meet him, had no momentum. As a result, the pair of them went down with all their three hundred and sixty pounds of weight, in a long, crashing fall, Watson underneath. He lay with his head touching the rear wall of the large room. The street was a hundred and fifty feet away, and he did some quick thinking. His first thought was to avoid trouble. He had no wish to get into the papers of this his childhood town where many of his relatives and family friends still lived.

So it was that he locked his arms around the man on top of him, held him close and waited for the help to come that must come in response to the crash of the fall. The help came — that is, six men ran in from the bar and formed about in a semicircle.

“Take him off, fellows!” Watson said. “I haven’t struck him, and I don’t want any fight.”

But the semicircle remained silent. Watson held on and waited. Patsy, after various vain efforts to inflict damage, made an overture.

“Leggo o’ me an’ I’ll get off o’ yeh,” said he.

Watson let go, but when Patsy scrambled to his feet he stood over his recumbent foe ready to strike.

“Get up!” Patsy commanded.

His voice was stern and implacable, like the voice of one calling to judgment, and Watson knew there was no mercy there.

“Stand back and I’ll get up,” he countered.

“If yer a gentleman get up,” quoth Patsy, his Celtic eyes aflame with wrath, his fist ready for a crushing blow.

At the same moment he drew his foot back to kick the other in the face. Watson blocked the kick with his crossed arms and sprang to his feet so quickly that he was in a clinch with his antagonist before the latter could strike. Holding him, Watson spoke to the onlookers.

“Take him away from me, fellows. You see I am not striking him. I don’t want to fight. I want to get out of here.”

The circle did not move or speak. Its silence was ominous and sent a chill to Watson’s heart. Patsy made an effort to throw him, which culmi nated in his putting Patsy on his back. Tearing loose from him, Watson sprang to his feet and made for the door. But the circle of men was interposed like a wall. He noticed the white, pasty faces, the kind that never see the sun, and knew that the men who barred his way were the night prowlers and preying beasts of the city jungle. By them he was thrust back upon the pursuing, bull-rushing Patsy.

nated in his putting Patsy on his back. Tearing loose from him, Watson sprang to his feet and made for the door. But the circle of men was interposed like a wall. He noticed the white, pasty faces, the kind that never see the sun, and knew that the men who barred his way were the night prowlers and preying beasts of the city jungle. By them he was thrust back upon the pursuing, bull-rushing Patsy.

Again it was a clinch, in which, in momentary safety, Watson appealed to the gang. And again his words fell on deaf ears. Then it was that he knew fear. For he had known of many similar situations in low dens like this, when solitary men were manhandled, their ribs and features caved in, themselves beaten and kicked to death. And he knew further that if he were to escape he must neither strike his assailant nor any of the men who opposed him.

Yet in him was righteous indignation. Under no circumstance could seven to one be fair. Also, he was angry, and there stirred in him the fighting beast that is in all men. But he remembered his wife and children, his unfinished book, the ten thousand rolling acres of the up-country ranch he loved so well. He even saw in flashing visions the blue of the sky, the golden sun pouring down on his flower-spangled meadows, the lazy cattle knee-deep in the brooks, and the flash of trout in the riffles. Life was good — too good for him to risk it for a moment’s sway of the beast. In short, Carter Watson was cool and scared.

His opponent, locked by his masterly clinch, was striving to throw him. Again Watson put him on the floor, broke away, and was thrust back by the pasty-faced circle to duck Patsy’s swinging right and effect another clinch. This happened many times. And Watson grew even cooler, while the baffled Patsy, unable to inflict punishment, raged wildly and more wildly. He took to batting with his head in the clinches. The first time, he landed his forehead flush on Watson’s nose. After that the latter, in the clinches, buried his face in Patsy’s breast. But the enraged Patsy batted on, striking his own eye and nose and cheek on the top of the other’s head. The more he was thus injured the more and the harder did Patsy bat.

This one-sided contest continued for twelve minutes. Watson never struck a blow and strove only to escape. Sometimes, in the free moments, circling about among the tables as he tried to win the door, the pasty-faced men gripped his coat-tails and flung him back at the swinging right of the on-rushing Patsy. Time upon time and times without end he clinched and put Patsy on his back, each time first whirling him around and putting him down in the direction of the door and gaining toward that goal by the length of the fall.

In the end, hatless, disheveled, with streaming nose and one eye closed, Watson won to the sidewalk and into the arms of a policeman.

“Arrest that man!” Watson panted.

“Hello, Patsy!” said the policeman. “What’s the mix-up?”

“Hello, Charley!” was the answer. “This guy comes in — ”

“Arrest that man, officer!” Watson repeated.

“G’wan! Beat it!” said Patsy.

“Beat it!” added the policeman. “If you don’t I’ll pull you in.”

“Not unless you arrest that man. He has committed a violent and unprovoked assault on me.”

“Is it so, Patsy?” was the officer’s query.

“Nah. Lemme tell you, Charley, an’ I got the witnesses to prove it, so help me God. I was settin’ in me kitchen eatin’ a bowl of soup, when this guy comes in an’ gets gay wid me. I never seen him in me born days before. He was drunk f — ”

“Look at me, officer,” protested the indignant sociologist. “Am I drunk?”

The officer looked at him with sullen, menacing eyes and nodded to Patsy to continue.

“This guy gets gay wid me. ‘I’m Tim McGrath,’ says he, ‘an’ I can do the likes of you,’ says he. ‘Put up yer hands.’ I smiles an’, wid that, bill, bill, he lands me twice an’ spills me soup. Look at me eye. I’m fair murdered.”

“What are you going to do, officer?” Watson demanded.

“Go on, beat it,” was the answer, “or I’ll pull you sure!”

Then the civic righteousness of Carter Watson flamed up.

“Mr. Officer, I protest — ”

But at that moment the policeman grabbed his arm with a savage jerk that nearly overthrew him.

“Come on, you’re pulled!”

“Arrest him, too!” Watson demanded.

“Nix on that play,” was the reply. “What did you assault him for, him apeacefully eatin’ his soup?”

II

Carter Watson was genuinely angry. Not only had he been wantonly assaulted, badly battered and arrested, but the morning papers without exception came out with lurid accounts of his drunken brawl with the proprietor of the notorious Vendome.

Not one accurate or truthful line was published. Patsy Horan and his satellites described the battle in detail. The one incontestable thing was that Carter Watson had been drunk. Thrice he had been thrown out of the place and into the gutter, and thrice he had come back, breathing blood and fire and announcing that he was going to clean out the place.

EMINENT SOCIOLOGIST JAGGED AND JUGGED

was the first headline he read on the front page, accompanied by a large portrait of himself. Other headlines were:

CARTER WATSON ASPIRED TO CHAMPIONSHIP HONORS

CARTER WATSON GETS HIS

NOTED SOCIOLOGIST ATTEMPTS TO CLEAN OUT A TENDERLOIN CAFE

CARTER WATSON KNOCKED OUT BY PATSY HORAN IN THREE ROUNDS

At the police court next morning, under bail, appeared Carter Watson to answer the complaint of the People versus Carter Watson for the latter’s assault and battery on one Patsy Horan. But first the prosecuting attorney, who was paid to prosecute all offenders against the People, drew him aside and talked with him privately.

“Why not let it drop?” said the prosecuting attorney. “I tell you what you do, Mr. Watson. Shake hands with Mr. Horan and we’ll drop the case right here. A word to the judge and the case against you will be dismissed.”

“But I don’t want it dismissed,” was the answer. “Your office being what it is, you should be prosecuting me instead of asking me to make up with this — this fellow.”

“Oh, I’ll prosecute you all right,” retorted the other.

“Also you will have to prosecute this Patsy Horan,” Watson advised; “for I shall now have him arrested for assault and battery.”

“You’d better shake and make up,” the prosecuting attorney repeated, with a threat in his voice.

The trials of both men were set for a week later, on the same morning, in Police Judge Witberg’s court.

“You have no chance,” Watson was told by an old friend of his boyhood, the retired manager of the biggest paper in the city. “Everybody knows you were beaten up by this man. His reputation is most unsavory. But it won’t help you in the least. Both cases will be dismissed. This will be because you are you. Any ordinary man would be convicted.”

“But I do not understand,” objected the perplexed sociologist. “Without warning I was attacked by this man and badly beaten. I did not strike a blow. I — ”

“That has nothing to do with it,” the other cut him off.

“Then what is there that has anything to do with it?”

“I’ll tell you. You are now up against the local police and political machine. Who are you? You are not even a legal resident in this town. You live up in the country. You haven’t a vote of your own here. Much less do you swing any votes. This dive proprietor swings a string of votes in his precinct — a mighty long string.”

“Do you mean to tell me that this Judge Witberg will violate the sacredness of his office and oath by letting this brute off?” Watson demanded.

“Watch him,” was the grim reply. “Oh, he’ll do it nicely enough! He will give an extra-legal, extra-judicial decision abounding in every word in the dictionary that stands for fairness and right.”

“But there are the newspapers,” Watson cried.

“They are not fighting the administration at present. They’ll give it to you hard. You see what they have already done to you.”

“Then these snips of boys on the police detail won’t write the truth.”

“They will write something so near like the truth that the public will believe it. They write their stories under instruction, you know. They have their orders to twist and color, and there won’t be much left of you when they get done. Better drop the whole thing right now. You are in bad.”

“But the trials are set.”

“Give the word and they’ll drop them now. A man can’t fight a machine unless he has a machine behind him — and shall I tell you a secret? Judge Witberg pays the taxes on Patsy Horan’s resort.”

“You don’t mean it?”

“No, I don’t. I am just telling you.”

III

But Carter Watson was stubborn. He was convinced that the machine would beat him, but all his days he had sought social experience, and this was certainly something new.

The morning of the trial the prosecuting attorney made another attempt to patch up the affair.

“If you feel that way I should like to get a lawyer to prosecute the case,” said Watson.

“No, you don’t!” said the prosecuting attorney. “I am paid by the People to prosecute, and prosecute I will. But let me tell you: You have no chance. We shall lump both cases into one, and you watch out!”

Judge Witberg looked good to Watson. He was a fairly young man, with an intelligent face, smiling lips and wrinkles of laughter in the corners of his black eyes. Looking at him and studying him, Watson felt almost sure that his old friend’s prognostication was wrong.

But Watson was soon to learn. Patsy Horan and the two of his satellites testified to a most colossal aggregation of perjuries. Watson could not have believed it possible without having experienced it. They denied the existence of the other four men. And of the two that testified, one claimed to have been in the kitchen, a witness to Watson’s unprovoked assault on Patsy, while the other, remaining in the bar, had witnessed Watson’s second and third rushes into the place as he attempted to annihilate the unoffending Patsy. The vile language ascribed to Watson was so voluminously and unspeakably vile that he felt they were injuring their own case — it was so impossible that he should utter such things. But when they described the brutal blows he had rained on poor Patsy’s face, and the chair he demolished when he vainly attempted to kick Patsy, Watson waxed secretly hilarious and at the same time sad. The trial was a farce; but such lowness of life was depressing to contemplate when he considered the long upward climb humanity must make.

Watson could not recognize himself, nor could his worst enemy have recognized him, in the swashbuckling, roughhousing picture that was painted of him. But, as in all cases of complicated perjury, rifts and contradictions in the various stories appeared. The judge somehow failed to notice them, while the prosecuting attorney and Patsy’s attorney shied off from them gracefully. Watson had not bothered to get a lawyer for himself, and he was now glad that he had not.

Still, he retained a semblance of faith in Judge Witberg when he went himself on the stand and started to tell his story.

“I was strolling casually along the street, your Honor,” Watson began, but was interrupted by the judge.

“We are not here to consider your previous actions,” bellowed Judge Witberg. “Who struck the first blow?”

“Your Honor,” Watson pleaded, “I have no witnesses of the actual fray, and the truth of my story can only be brought out by telling the story fully — ”

Again he was interrupted.

“We do not care to publish any magazines here,” Judge Witberg roared, looking at him so fiercely and malevolently that Watson could scarcely bring himself to believe that this was the same man he had studied a few minutes previously.

“Who struck the first blow?” Patsy’s attorney asked.

The prosecuting attorney interposed, demanding to know which of the two cases lumped together this was, and by what right Patsy’s lawyer, at that stage of the proceedings, should take the witness. Patsy’s attorney fought back. Judge Witberg interfered, professing no knowledge of any two cases being lumped together. All this had to be explained. Battle royal raged, terminating in both attorneys apologizing to the court and to each other. And so it went, and to Watson it had the seeming of a group of pickpockets ruffling and bustling an honest man as they took his purse. The machine was working, that was all.

“Why did you enter this place of unsavory reputation?” was asked him.

“It has been my custom for many years, as a student of economics and sociology, to acquaint myself — ”

But this was as far as Watson got.

“We want none of your ologies here,” snarled Judge Witberg. “It is a plain question. Answer it plainly. Is it true or not true that you were drunk? That is the gist of the question.”

When Watson attempted to tell how Patsy had injured his face in his attempts to bat with his head, Watson was openly scouted and flouted, and Judge Witberg again took him in hand.

“Are you aware of the solemnity of the oath you took to testify to nothing but the truth on this witness stand?” the judge demanded. “This is a fairy story you are telling. It is not reasonable that a man would so injure himself, and continue to injure himself, by striking the soft and sensitive parts of his face against your head. You are a sensible man. It is unreasonable, is it not?”

“Men are unreasonable when they are angry,” Watson answered meekly.

Then it was that Judge Witberg was deeply outraged and righteously wrathful.

“What right have you to say that?” he cried. “It is gratuitous. It has no bearing on the case. You are here as a witness, sir, of events that have transpired. The court does not wish to hear any expressions of opinion from you at all.”

“I but answered your question, your Honor,” Watson protested humbly.

“You did nothing of the sort,” was the next blast. “And let me warn you, sir, let me warn you that you are laying yourself liable to contempt by such insolence. And I will have you know that we know how to observe the law and the rules of courtesy down here in this little courtroom. I am ashamed of you.”

And, while the next punctilious legal wrangle between the attorneys interrupted his tale of what happened in the Vendome, Carter Watson, without bitterness, amused and at the same time sad, saw rise before him the machines, large and small, that dominated his country, the unpunished and shameless grafts of a thousand cities perpetrated by the spidery and verminlike creatures of the machines. Here it was before him, a courtroom and a judge bowed down in subservience by the machine to a divekeeper who swung a string of votes. Petty and sordid as it was, it was one face of the many-faced machine that loomed colossally in every city and state, in a thousand guises overshadowing the land.

A familiar phrase rang in his ears: “It is to laugh.” At the height of the wrangle he giggled once aloud, and earned a sullen frown from Judge Witberg. Worse a myriad times, he decided, were these bullying lawyers and this bullying judge than the bucko mates in first-quality hellships, who not only did their own bullying but protected themselves as well. These petty rapscallions, on the other hand, sought protection behind the majesty of the law. They struck, but no one was permitted to strike back, for behind them were the prison cells and the clubs of the stupid policemen — paid and professional fighters and beaters-up of men. Yet he was not bitter. The grossness of it was forgotten in the simple grotesqueness of it.

Nevertheless, hectored and heckled though he was, he managed in the end to give a simple, straightforward version of the affair, and despite a belligerent cross-examination his story was not shaken in any particular. Quite different it was from the perjuries of Patsy.

Both Patsy’s attorney and the prosecuting attorney rested their cases, letting everything go before the court without argument. Watson protested against this, but was silenced when the prosecuting attorney told him that he was the public prosecutor and knew his business.

“Patrick Horan has testified that he was in danger of his life and that he was compelled to defend himself,” Judge Witberg’s verdict began. “Mr. Watson has testified to the same thing. Each has sworn that the other struck the first blow; each has sworn that the other made an unprovoked assault on him. It is an axiom of the law that the defendant should be given the benefit of the doubt. A very reasonable doubt exists. Therefore, in the case of the People versus Carter Watson the benefit of the doubt is given to said Carter Watson and he is herewith ordered discharged from custody. The same reasoning applies to the case of the People versus Patrick Horan. He is given the benefit of the doubt and discharged from custody. My recommendation is that both defendants shake hands and make up.”

In the afternoon papers the first headline that caught Watson’s eye was:

CARTER WATSON ACQUITTED

In the second paper it was:

CARTER WATSON ESCAPES A FINE

But what capped everything was the one beginning:

CARTER WATSON A GOOD FELLOW

In the text he read how Judge Witberg had advised both fighters to shake hands, which they promptly did. Further, he read:

“‘Let’s have a nip on it,’ said Patsy Horan.

“‘Sure!’ said Carter Watson.

“And arm in arm they ambled to the nearest saloon.”

IV

Now from the whole adventure Watson carried away no bitterness. It was a social experience of a new order and it led to the writing of another book, which he entitled Police Court Procedure: A Tentative Analysis.

One summer morning a year later, on his ranch, he left his horse and clambered through a miniature canyon to inspect the rock ferns he had planted the previous winter. Emerging from the upper end of the canyon he came out on one of his flower-spangled meadows, a delightful, isolated spot screened from the world by low hills and clumps of trees. And here he found a man, evidently on a stroll from the summer hotel down at the little town a mile away. They met face to face and the recognition was mutual. It was Judge Witberg. Also it was a clear case of trespass, for Watson had trespass signs up on his boundaries, though he never enforced them.

Judge Witberg held out his hand, which Watson refused to see.

“Politics is a dirty trade, isn’t it, Judge?” he remarked. “Oh, yes! I see your hand, but I don’t care to take it. The papers said I shook hands with Patsy Horan after the trial. You know I didn’t; but let me tell you that I’d a thousand times rather shake hands with him and his vile following of curs than with you.”

Judge Witberg was painfully flustered, and as he hemmed and hawed and essayed to speak, Watson, looking at him, was struck by a sudden whim, and he determined on a grim and facetious antic.

“I should scarcely expect any animus from a man of your acquirements and knowledge of the world,” the judge was saying.

“Animus?” Watson replied. “Certainly not. I haven’t such a thing in my nature. And to prove it let me show you something curious, something you have never seen before.” Casting about him, Watson picked up a rough stone the size of his fist. “See this? Watch me.”

So saying, Carter Watson tapped himself a sharp blow on the cheek. The stone laid the flesh open and the blood spurted forth.

“The stone was too sharp,” he announced to the astounded police judge, who thought he had gone mad. “I must bruise it a trifle. There is nothing like being realistic in such matters.”

Whereupon Carter Watson found a smooth stone and with it pounded his cheek nicely several times.

“Ah!” he cooed. “That will turn beautifully green and black in a few hours. It will be most convincing.”

“You are insane,” Judge Witberg quavered.

“Don’t use such vile language to me,” said Watson. “You see my bruised and bleeding face? You did that with that right hand of yours. You hit me twice — biff, biff. It is a brutal and unprovoked assault. I am in danger of my life. I must protect myself.”

Judge Witberg backed away in alarm before the menacing fists of the other.

“If you strike me I’ll have you arrested,” Judge Witberg threatened.

“That is what I told Patsy,” was the answer. “And do you know what he did when I told him that?”

“No.”

“That!”

And at the same moment Watson’s right fist landed flush on Judge Witberg’s nose, putting that legal gentleman over on his back on the grass.

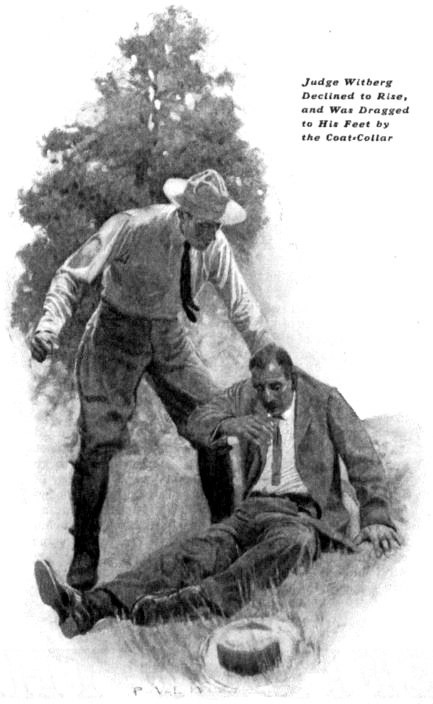

“Get up!” commanded Watson. “If you are a gentleman, get up — that’s what Patsy told me, you know.”

Judge Witberg declined to rise, and was dragged to his feet by the coat-collar, only to have one eye blacked and be put on his back again. After that it was a red Indian massacre. Judge Witberg was humanely and scientifically beaten up. His cheeks were boxed, his ears cuffed, and his face was rubbed in the turf. And all the time Watson exposited the way Patsy Horan had done it. Occasionally and very carefully the facetious sociologist administered a real bruising blow. Once, dragging the poor judge to his feet, he deliberately bumped his own nose on the gentleman’s head. The nose promptly bled.

“See that!” cried Watson, stepping back and deftly shedding his blood all down his own shirtfront. “You did it. With your fist you did it. It is awful. I am fair murdered. I must again defend myself.”

And once more Judge Witberg impacted his features on a fist and was sent down to grass.

“I will have you arrested,” he sobbed as he lay.

“That’s what Patsy said.”

“A brutal [sniff, sniff] and unprovoked [sniff, sniff] assault.”

“That’s what Patsy said.”

“I will surely have you arrested.”

“Speaking slangily, not if I can beat you to it.”

And with that Carter Watson departed down the canyon, mounted his horse and rode to town.

An hour later as Judge Witberg limped up the grounds to his hotel he was arrested by a village constable on a charge of assault and battery preferred by Carter Watson.

V

“Your honor,” Watson said next day to the village justice, a well-to-do farmer and graduate thirty years before from a cow college, “since this Sol Witberg has seen fit to charge me with battery, following upon my charge of battery against him, I would suggest that both cases be lumped together. The testimony and the facts are the same in both cases.”

To this the justice agreed, and the double case proceeded. Watson, as prosecuting witness, first took the stand and told his story.

“I was picking flowers,” he testified — “picking flowers on my own land, never dreaming of danger. Suddenly this man rushed upon me from behind the trees. ‘I am the Dodo,’ he says, ‘and I can do you to a frazzle. Put up your hands.’ I smiled; but, with that, biff, biff, he struck me, knocking me down and spilling my flowers. The language he used was frightful. It was an unprovoked and brutal assault. Look at my cheek. Look at my nose. I could not understand it. He must have been drunk. Before I recovered from my surprise he had administered this beating. I was in danger of my life and was compelled to defend myself. That is all, your Honor, though I must say in conclusion that I cannot get over my perplexity. Why did he say he was the Dodo? Why did he so wantonly attack me?”

And thus was Sol Witberg given a liberal education in the art of perjury. Often from his high seat he had listened indulgently to police court perjuries in cooked-up cases; but for the first time perjury was directed against him, and he no longer sat above the court, with bailiffs, the policemen’s clubs and prison cells behind him.

“Your Honor,” he cried, “never have I heard such a pack of lies told by so barefaced a liar — ”

Watson here sprang to his feet.

“Your Honor, I protest. It is for your Honor to decide truth or falsehood. The witness is on the stand to testify to actual events that have occurred. His personal opinion upon things in general and upon me has no bearing on the case whatever.”

The justice scratched his head and waxed phlegmatically indignant.

“The point is well taken,” he decided. “I am surprised at you, Mr. Witberg, claiming to be a judge and skilled in the practice of the law, and yet being guilty of such unlawyerlike conduct. Your manner, sir, and your methods remind me of a shyster. This is a simple case of assault and battery. We are here to determine who struck the first blow, and we are not interested in your estimates of Mr. Watson’s personal character. Proceed with your story.”

Sol Witberg would have bitten his bruised and swollen lip in chagrin had it not hurt so much. But he contained himself and told a simple, straightforward, truthful story.

“Your Honor,” Watson said, “I would suggest that you ask him what he was doing on my premises.”

“A very good question. What were you doing, sir, on Mr. Watson’s premises?”

“I did not know they were his premises.”

“It was a trespass, your Honor,” Watson cried. “The warnings are posted conspicuously.”

“I saw no warnings,” said Sol Witberg.

“I have seen them myself,” snapped the justice. “They are very conspicuous. And I would warn you, sir, that if you palter with the truth in such little matters you may darken your more important statements with suspicion. Why did you strike Mr. Watson?”

“Your Honor, as I have testified, I did not strike a blow.”

The justice looked at Carter Watson’s bruised and swollen visage, and turned to glare at Sol Witberg.

“Look at that man’s cheek!” he thundered. “If you did not strike a blow how comes it that he is so disfigured and injured?”

“As I testified — ”

“Be careful,” the justice warned.

“I will be careful, sir. I will say nothing but the truth. He struck himself with a rock. He struck himself with two rocks.”

“Does it stand to reason that a man, any man not a lunatic, would so injure himself and continue to injure himself by striking the soft and sensitive parts of his face with a stone?” interposed Watson.

“It sounds like a fairy story,” was the justice’s comment. “Mr. Witberg, had you been drinking?”

“No, sir.”

“Do you ever drink?”

“On occasion.”

The justice meditated on this answer with an air of astute profundity.

Watson took advantage of the opportunity to wink at Sol Witberg, but that much-abused gentleman saw nothing humorous in the situation.

“A very peculiar case, a very peculiar case,” the justice announced as he began his verdict. “The evidence of the two parties is flatly contradictory. There are no witnesses outside the two principals. Each claims the other committed the assault, and I have no legal way of determining the truth. But I have my private opinion, Mr. Witberg, and I would recommend that henceforth you keep off of Mr. Watson’s premises and keep away from this section of the country — ”

“This is an outrage!” Sol Witberg blurted out.

“Sit down, sir!” was the justice’s thundered command. “If you interrupt the court in this manner again I shall fine you for contempt. And I warn you I shall fine you heavily — you, a judge yourself, who should be conversant with the courtesy and dignity of courts. I shall now give my verdict:

“It is a rule of law that the defendant shall be given the benefit of the doubt. As I have said, and I repeat, there is no legal way for me to determine who struck the first blow. Therefore, and much to my regret” — here he paused and glared at Sol Witberg — “in each of these cases I am compelled to give the defendant the benefit of the doubt. Gentlemen, you are both dismissed.”

“Let us have a nip on it,” Watson said to Witberg as they left the courtroom; but that outraged person refused to lock arms and amble to the nearest saloon.

Illustrated by P.V.E. Ivory (©SEPS)

Rockwell Video Minute: The Holdout

See all of the videos in our Rockwell Video Minute series.

Featured image: Norman Rockwell / SEPS

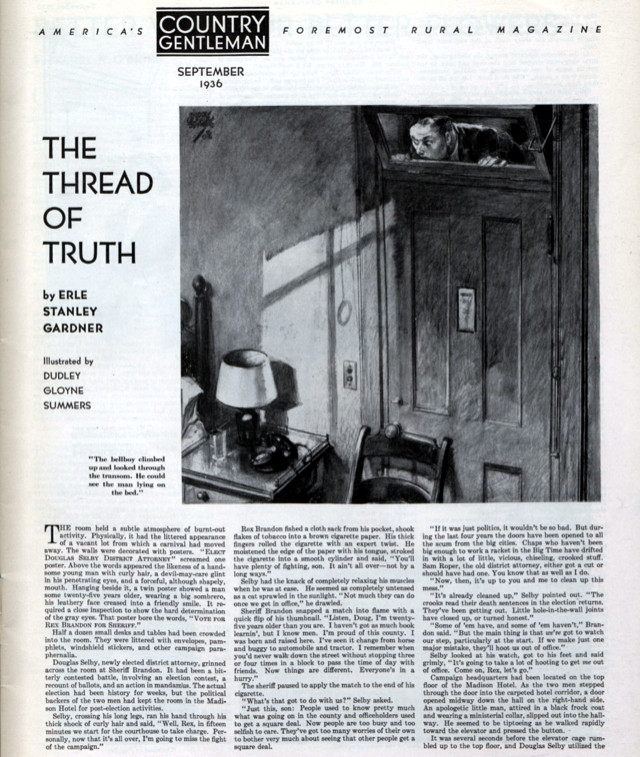

“The Thread of Truth, Part II” by Erle Stanley Gardner

When he died, in 1970, Erle Stanley Gardner was the best-selling American fiction author of the century. His detective stories sold all over the globe, especially those with his most famous defense attorney protagonist, Perry Mason. His no-nonsense prose and neat, satisfying endings delighted detective fans for decades. Gardner wrote several stories that were serialized in the Post. In Country Gentleman, his 1936 serial “The Thread of Truth” follows a fresh D.A. in a clergyman murder case that comes on his first day on the job.

Published on October 1, 1936

District Attorney Douglas Selby and Sheriff Rex Brandon, both newly elected in a bitter campaign which swept Sam Roper and his henchman out of authority in Madison City, agreed that they must not muff their first important case. For while The Clarion, and incidentally the lovely young reporter, Sylvia Martin, were loyally supporting Selby, the opposition newspaper, The Blade, was alert for a chance to blast the fighting young newcomer into disgrace.

The death of Rev. Charles Brower, apparently of an overdose of sleeping potion, in Room 321 of the Madison Hotel did not look like an important case. Sleek George Cushing, manager of the hotel, insisted that the little minister had died a natural death. Selby thought so, too, until Mrs. Charles Brower arrived to declare positively that the man was not her husband. Yet the minister’s effects included many things identifying him as Charles Brower, including an unfinished letter in his portable typewriter addressed to the wife, who was repudiating him.

There were also in the dead man’s belongings an expensive camera; a sheaf of clippings about Shirley Arden, famous actress of Hollywood, less than one hundred miles away; and another batch of clippings concerning litigation in the Madison City courts over the Perry estate.

Who was the little minister, if he were not Charles Brower? Douglas Selby set out to find the answer. He discovered that the impoverished minister had left, in the hotel safe, a rose-perfumed envelope containing five thousand dollars. He discovered that Shirley Arden, incognito, had occupied a fifth-floor room, from which Selby himself had seen the minister emerge on the day before his death. And then — the examining physician reported the cause of death — a murderous dose of morphine.

VII

Selby rang Sheriff Brandon on the telephone and said, “Have you heard Trueman’s report on that Brower case?”

“Yes, I just talked with him. What do you think of it?”

“I think it’s murder.”

“Listen, Doug,” Rex said, “we’ve got to work fast on this thing. The Blade will start riding us.”

“That’s all right. We’ve got to expect to be roasted once in a while. But let’s chase down all the clues and see if we can’t keep one jump ahead of the knockers. Did you get in touch with the San Francisco optician?”

“Yes, I sent him a wire.”

“Better get him on the telephone and see if you can speed things up any. He may be able to give us some information. Now, here’s another thing. Room 323 had been rented to a Mr. and Mrs. Leslie Smith, of Hollywood. I told Cushing to get their address from the register. I wish you’d get that information; telephone the Hollywood police station and see if you can get a line on the couple. If you can’t, wire the motor-vehicle department and find out if a Leslie Smith, of Hollywood. owns an automobile, and get his residence from the registration certificate. Also, see if a Leslie Smith had a car stored in one of the garages near the hotel.”

“Of course,” the sheriff pointed out, “he might have been using a fictitious name.”

“Try it, anyway,” Selby said. “Let’s go through the facts in this case with a fine-tooth comb. They can’t expect us to be infallible, Rex. Lots of murders are never solved, even in cities where they have the most efficient police forces. What we have to guard against is slipping up on some little fact where a Blade reporter can give us the horselaugh. Figure the position we’ll be in if The Blade solves this murder while we’re still groping around in the dark.”

“I get you,” Brandon said grimly. “Leave it to me. I’ll turn things upside down and inside out.”

“One other thing,” Selby said. “When you get George Cushing in the sweatbox, he’ll probably give you some information about a certain picture actress who was in the hotel. You don’t need to bother about that. We don’t want any publicity on it right at the present time, and I’ve been in touch with her manager. They’re going to be up here at eight o’clock tonight at my office. I’ll find out if there’s anything to it and let you know. You’d better arrange to sit in on the conference.”

“Okay,” Brandon said, “I’ll get busy. You stick around and I’ll probably have something for you inside of half an hour.”

As the district attorney hung up the telephone his secretary brought him a telegram from the chief of police of Millbank, Nevada.

Selby read:

ANSWERING YOUR WIRE MARY BROWER FIVE FEET FOUR INCHES WEIGHT ONE HUNDRED SIXTY POUNDS AGE AS GIVEN TO REGISTRATION AUTHORITIES FIFTY-TWO RESIDES SIX THIRTEEN CENTER STREET THIS CITY LAST SEEN LEAVING FOR RENO TO TAKE PLANE FOR LOS ANGELES REPORTED TO FRIENDS HUSBAND HAD DIED IN SOUTHERN CALIFORNIA WAS WEARING BROWN SUIT BROWN GLOVES AND DARK BROWN COAT TRIMMED WITH FOX FUR STOP CHARLES BROWER ECCENTRIC PASTOR NO DENOMINATION CONDUCTED STREET SERVICES FOR YEARS THIS CITY AND DENVER WORKED WITH DELINQUENTS AND UNFORTUNATES STOP RECENTLY HAS BEEN SOLICITING FUNDS FROM BUSINESSMEN AND OTHERS TO ERECT NONDENOMINATIONAL CHURCH STOP LARGEST CONTRIBUTOR WAS STOCKBROKER IN DENVER WHO HAD KNOWN BROWER FOR YEARS BECAME FINANCIALLY INVOLVED THROUGH UNFORTUNATE SPECULATION AND CREDITORS THREATENED TO ATTACH CONTRIBUTION IN BROWER’S HANDS UPON GROUND DONATION NOT COMPLETED UNTIL CHURCH CONSTRUCTED STOP BROWER WITHDREW MONEY FROM BANK AND DISAPPEARED CLAIMING NERVOUS BREAKDOWN FRIENDS BELIEVE HE IS SEEKING TO AVOID DISASTROUS LITIGATION AND WILL RETURN WITH CONTRACT FOR BUILDING AWARDED STOP IS FIVE FEET SEVEN INCHES TALL WEIGHS ONE HUNDRED THIRTY FIVE POUNDS HAS GRAY EYES AND HIGH CHEEKBONES REGISTERED AS REPUBLICAN GIVING AGE AS FIFTY-SIX DRIVING SMALL NINETEEN TWENTY EIGHT SEDAN LICENSE SIX FIVE FOUR THREE EIGHT LAST SEEN WEARING BLUE SERGE SUIT SOFT COLLAR SHIRT BLUE AND WHITE TIE AND TAN LOW SHOES HAS SMALL TRIANGULAR SCAR BACK OF RIGHT EAR

Selby looked at the wire, nodded and said, “There’s a man who knows his job.”

Amorette Standish let her curiosity show in her voice.

“Were you wondering if she really is Mrs. Brower?”

“I was,” he said.

“And the dead man?” she asked. “Was he Mr. Brower?”

“I don’t think so. The woman says he isn’t, and the description doesn’t fit. Ring up the coroner and ask him to look particularly for the small triangular scar mentioned in the wire. I don’t think he’ll find it, but we’ll look anyway.”

As his secretary took the telegram and left the room, Selby got to his feet and began a restless pacing of the office. At length he sat down at his desk and started scribbling a wire to the chief of police at Millbank, Nevada.

“Ascertain if possible,” he wrote, “if Brower had a friend, probably a minister, between forty-five and fifty-five, about five feet five inches, weight about hundred and twenty, small-boned, dark hair, gray at temples, small round bald spot top and back of head. Interested in photography. Probably had made several fruitless attempts to sell scenarios Hollywood studios. Interested in motion pictures. Last seen wearing black frock coat, well-worn and shiny black trousers, black high shoes. Eyes blue. Manner very self-effacing. Enunciation very precise, as though accustomed public speaking from pulpit. Owns Typco portable typewriter. Wire reply earliest available moment. Important. Thanks for co-operation.” Selby gave the telegram to Amorette Standish to be sent. His telephone was ringing before she had left the office. He took down the receiver and heard Sheriff Brandon’s voice.

“Have some news for you, Doug,” the sheriff said.

“Found out who he was?”

“No, not yet.”

“Talk with that optician in San Francisco?”

“Yes. He got my wire, but had been pretty busy and had just hit the high spots going over his records. He hadn’t found anything. I don’t think he’d been trying very hard. I put a bee in his bonnet, told him to check over every prescription he had in his files if necessary. He said the prescription wasn’t particularly unusual. I told him to make a list of every patient he had who had that prescription and send me a telegram.”

“What else?” Selby asked.

Brandon lowered his voice.

“Listen, Doug,” he said cautiously, “the opposition are going to try to put us on the spot.”

“Go ahead,” Selby said.

“Jerry Summerville, who runs The Blade, has imported a crack mystery man from Los Angeles, a fellow by the name of Carl Bittner. He’s been a star reporter for some of the Los Angeles dailies. I don’t know how much money it cost, or who’s putting it up, but Summerville put in the call this morning and Bittner is here in town now. He’s been asking questions of the coroner and trying to pump Cushing.”

“What did Cushing tell him, do you know?”

“No. He pulled a fast one with Cushing. He said he was a special investigator and sort of gave Cushing to understand he was from your office. Cushing talked a little bit. I don’t know how much … Suppose we could throw a scare into this bird for impersonating an officer?”

“Special investigator doesn’t mean anything,” Selby said slowly. “Let’s go slow on bothering about what the other people are doing, Rex, and solve the case ourselves. After all, we have all the official machinery at our disposal, and we’ve got a head start.”

“Not very much of a head start,” the sheriff said. “We collect the facts and the other fellows can use them.”

“We don’t need to tell them all we know,” Selby pointed out.

“That’s one of the things I wanted to ask you about. Suppose we clamp down the lid on information?”

“That’s okay by me.”

“All right, we’ll do it. Now here’s something else for you. Mr. and Mrs. Leslie Smith are phonies. They gave an address of 3350 Blair Drive. There isn’t any such number. There are about fifty automobiles registered to Leslie Smiths in various parts of the state.”

“Okay,” Selby said after a moment, “it’s up to you to run down all fifty of those car owners.”

“I was talking with Cushing,” Brandon went on, “and he says they were a couple of kids who might have been adventuring around a bit and used the first alias that came into their heads.”

“Cushing may be right,” Selby rejoined, “but we’re solving this case, he isn’t. It stands to reason,that someone got into the minister’s room through one of the adjoining rooms. That chair being propped under the doorknob would have kept the door of 321 from opening. Both doors were locked on 323. I’m inclined to favor 319.”

“But there wasn’t anyone in 319 at the time.”

Selby said, “Let’s make absolutely certain of that, Rex. I don’t like the way Cushing is acting in this thing. He’s not co-operating as well as he might. Suppose you get hold of him and throw a scare into him.

“And here’s something else,” Selby went on. “I noticed that the writing on the letter which had been left in the typewriter was nice neat typewriting, almost professional in appearance.”

“I hadn’t particularly noticed that,” the sheriff said, after a moment, “but I guess perhaps you’re right.”

“Now, then, on the scenario, which was in his briefcase,” Selby pointed out, “the typing was ragged, the letters in the words weren’t evenly spaced. There were lots of strike-overs and the punctuation was rotten. Suppose you check up and see if both the scenario and the letter were written on the same typewriter.”

“You mean two different people wrote them, but on the same machine?”

“Yes. It fits in with the theory of murder. By checking up on that typing we can find out a little more about it. Now, Rex, we should be able to find out more about this man. How about labels in his clothes?”

“I’m checking on that. The coat was sold by a firm in San Francisco. There weren’t any laundry marks on his clothes. But I’ll check up on this other stuff, Doug, and let you know. Keep your head, son, and don’t worry. We can handle it all right. G’by.”

Selby hung up the telephone as Amorette Standish slipped in through the door and said in a low voice, “There’s a man in the outer office who says he has to see you upon a matter of the greatest importance.”

“Won’t he see one of the deputies?”

“No.”

“What’s his name?”

“Carl Bittner.”

Selby nodded slowly. “Show him in,” he said.

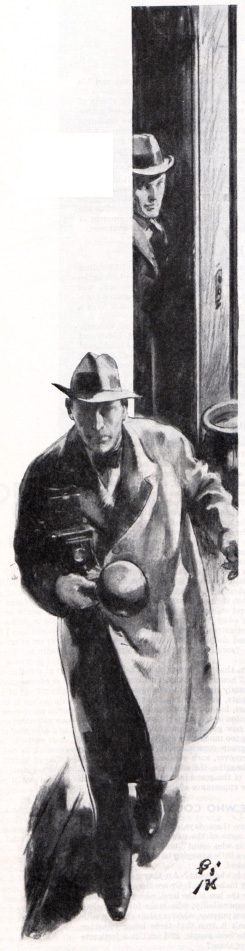

Carl Bittner was filled with bustling efficiency as he entered the room. Almost as tall as Selby, he was some fifteen years older. His face was thin, almost to the point of being gaunt; high cheekbones and thin lips gave him a peculiarly lantern-jawed appearance.

“I’m Bittner,” he said. “I’m with The Blade. I’m working on this murder case. What have you to say about it?”

“Nothing,” Selby said.

Bittner raised his eyebrows in surprise. “I’ve been working on some of the large dailies in Los Angeles,” he said. “Down there the district attorney co-operates with us and gives us any information he has.”

“It’s too bad you left there, then,” Selby said.

“The idea is,” Bittner went on, “that newspaper publicity will frequently clear up unexplained circumstances. Therefore, the district attorney feels it’s good business to co-operate with the newspapers.”

“I’m glad he does.”

“Don’t you feel that way?”

“No.”

“There’s some chance we could identify the body, if you’d tell us everything you know.”

“Just what information did you want?”

“Everything you know,” Bittner said, dropping into a chair, lighting a cigarette and making himself thoroughly at ease.

“So far,” Selby said, “I have no information which would enable me to identify the dead man.”

“Don’t know anything about him, eh?”

“Virtually not a thing.”

“Wasn’t he mixed up with some Hollywood picture actress?”

“Was he?”

“I’m asking you.”

“And I’m asking you.”

“Don’t some of your investigations lead you to believe there’s a picture actress mixed up in the case?”

“I can’t very well answer that question.”

“Why?”

“As yet I haven’t correlated the various facts.”

“When do you expect to correlate them?”

“I don’t know.”

Bittner got to his feet, twisted his long mouth into a grin and said, “Thank you very much, Mr. Selby. The Blade will be on the street in about two hours. I’ll just about have time to get your antagonistic attitude written up against the deadline. Call me whenever you have anything new. Good-by.”

He slammed the door of Selby’s office triumphantly, as though he had succeeded in getting the district attorney to say exactly what he wanted said.

VIII

Selby switched on the lights in his office and read the terse telegram he had received from the chief of police at Millbank, Nevada:

BROWER HAD MANY FRIENDS AMONG MINISTERS IMPOSSIBLE IDENTIFY FRIEND MENTIONED FROM DESCRIPTION

He consulted his wrist watch. Shirley Arden and Trask should arrive to keep their appointment within fifteen minutes.

Selby spread out The Blade on his desk. Big headlines screamed across the front page: SHERIFF AND DISTRICT ATTORNEY BAFFLED BY CRIME. NEW AND INCOMPETENT OFFICIALS ADMIT HELPLESSNESS — REFUSE AID OF PRESS — UNIDENTIFIED CLERGYMAN MURDERED IN DOWNTOWN HOTEL!

There followed a more or less garbled account of the crime, but that which made Selby’s jaw clench was a column of “Comment” under the by-line of Carl Bittner, written with the technique of a mud-slinging metropolitan newspaper reporter.

“When the district attorney, Selby, was interviewed at a late hour this afternoon,” the article stated, “he admitted he had no information whatever which would be of any value in solving the murder. This, in spite of the fact representatives of The Blade have been able to uncover several significant facts which will probably clear up the mystery, at least as to the identity of the murdered man.”

“For some time a rumor has been rife that a prominent Hollywood picture actress figures in the case, that for reasons best known to himself District Attorney Selby is endeavoring to shield this actress. Pressed for information upon this point, Selby flew into a rage and refused to answer any questions. When it was pointed out to him that an identification of the victim, perhaps a solution of the crime itself, depended upon enlisting the aid of the press, he obstinately refused to divulge any information whatever, despite his admission that he was groping entirely in the dark.

“It is, of course, well known that whenever the breath of scandal fastens itself upon any prominent actress great pressure is brought to bear upon all concerned to hush matters up. The Blade has, however, pledged itself to discover the facts and give the news to its readers. It is to be regretted that the district attorney cannot recognize he is not a ruler, but a public servant. He is employed by the taxpayers, paid from tax moneys, and has taken an oath to faithfully discharge the duties of his office. He is young, untried and, in matters of this sort, inexperienced. Citizens of this community may well anticipate a carnival of crime as the crooks realize the type of man who has charge of law enforcement.”

“During the campaign, Selby was ready enough with his criticisms of Roper’s methods of conducting the office; but now that he has tried to take over the reins, his groping, bewildered attempts to solve a case which Roper would have taken in his stride, show only too well the cost to the public of discharging a faithful and efficient servant merely because of the rantings of some youth whose only qualification for the position is that he wants the prestige which goes with the title.”

A bitter column on the editorial page dealt with the fact that, as had been predicted by The Blade, Rex Brandon and Douglas Selby, while they were perhaps well-meaning, were utterly incompetent to handle a murder case such as the mysterious death of the unidentified clergyman. Had the voters retained Sam Roper in office, the editorial said, there was little doubt but what that veteran prosecutor would have by this time learned the identity of the dead man and probably had the murderer behind bars. Certainly the community would have been spared the humiliation of having a sheriff and a district attorney engage in such a comedy of errors as had resulted in bringing to an unfortunate woman the false information that her husband was dead. Roper would undoubtedly have made an investigation before jumping at such a false and erroneous conclusion.

Selby squared his shoulders.

All right, they wanted to fight, did they? Very well, he’d fight it out with them.

He heard a knock on his door and called, “Come in.”

The door opened and Selby saw a man nearly six feet tall, weighing well over two hundred pounds, smiling at him from the doorway.

The visitor wore a checked coat. His well-manicured hands adjusted the knot of his scarf as he smiled and said, in a deep, dramatic voice, “Ah, Mr. Selby, I believe? It is a pleasure.”

“You’re Trask?” Selby asked.

The big man bowed and smiled.

“Come in,” Selby said, “and tell Miss Arden to come in.”

“Miss Arden — er — er — unfortunately is not able to be present, Mr. Selby. As you may or may not know, Miss Arden’s nerves have been bothering her somewhat of late. She has been working under a terrific strain and … ”

“Where is she?” Selby interrupted, getting to his feet.

“At the close of the shooting this afternoon,” Trask said, “Miss Arden was in an exceedingly nervous condition. Her personal physician advised her … ”

“Where is she?”

“She — er — went away.”

“Where?”

“To the seclusion of a mountain resort where she can get a change in elevation and scenery and complete rest.”

“Where?”

“I am afraid I am not at liberty to divulge her exact location. The orders of her physician were most explicit.”

“Who’s her physician?”

“Dr. Edward Cartwright.”

Selby scooped up the telephone. “You come in and sit down,” he said to Trask; and, into the telephone, “This is Douglas Selby, the district attorney, speaking. I want to talk with Dr. Edward Cartwright in Los Angeles. I’ll hold the wire.”

Standing with his feet spread apart, his jaw thrust forward, the receiver of the telephone held in his left hand, he said to Trask, “That’s what I get for giving a heel like you a chance to double-cross me. It won’t happen again.”

Trask strode toward him, his eyes glowering with indignation. “Are you referring to me?” he demanded in a loud, booming voice. “Are you calling me a heel? Are you intimating that I double-crossed you because Miss Arden’s health has been jeopardized by overwork?”

“You’re damned right I am,” Selby said. “I’ll tell you more about it when I’ve talked with this doctor on the telephone.”

Into the telephone he said, “Hello! Rush through that call.”

A woman’s voice said, “Doctor Cartwright’s residence.”

Selby listened while the long-distance operator said, “The district attorney’s office at Madison City is calling Doctor Cartwright.”

“I’m afraid Doctor Cartwright can’t come to the telephone,” the woman’s voice said.

Selby interrupted. “I’ll talk with whoever’s on the phone,” he said.

“Very well,” the operator told him.

“Who is this?” Selby asked.

“This is Mrs. Cartwright.”

“All right,” Selby said, “this is Douglas Selby. I’m the district attorney at Madison City. You put Doctor Cartwright on the telephone.”

“But Doctor Cartwright has given orders that he is not to be disturbed.”

“You tell Doctor Cartwright he can either talk on the telephone or I’ll have him brought up here and he can do his talking in front of a grand jury.”

“But — you couldn’t do that,” the woman protested.

“That,” Selby remarked, “is a matter of opinion. Please convey my message to Doctor Cartwright.”

“He’s very tired. He left orders that … ”

“Convey that message to Doctor Cartwright,” Selby said, “or I’ll get a statement from him which will be made at my convenience rather than at his.”

There was a moment’s pause and the woman’s voice said dubiously, “Very well, just hold the phone a moment.”

Trask interrupted to say, “You can’t do this, Selby. You’re getting off on the wrong foot. Now I want to be friendly with you.”

“You,” Selby told him, “shut up. You promised me to have Shirley Arden here at eight o’clock. I’m already being put on the pan for falling for this Hollywood hooey. I don’t propose to be made the goat.”

“If you’re going to be pasty about it,” Trask said with an air of injured dignity, “it happens that I know my legal rights in the premises and . . .”

A man’s voice said “Hello” on the telephone, and Selby said, “Shut up, Trask … Hello! Is this Doctor Cartwright?”

“Yes.”

“You’re the Doctor Cartwright who attends Shirley Arden, the picture actress?”

“I have attended her on occasion, yes.”

“When did you last see her?”

“What’s the object of this inquiry?”

“Miss Arden was to have been in my office this evening. She isn’t here. I want to know why.”

“Miss Arden was in an exceedingly nervous condition.”

“When did you see her?”

“This afternoon.”

“What time?”

“About three o’clock.”

“What did you tell her?”

Doctor Cartwright’s voice became very professional. “I found that her pulse was irregular, that her blood pressure was higher than should have been the case. There was some evidence of halitosis, indicating a nervous indigestion. She complained of migraine and general lassitude. I advised a complete rest.”

“Did you advise her specifically not to keep her appointment with me?”

“I advised her not to engage in any activity which would cause undue excitement or nervousness.”

“Did you advise her not to keep her appointment with me?”

“I advised her to seek a secluded mountain resort where she could be quiet for a few days.”

“Did you advise her not to keep her appointment with me?”

“I told her that it would be unwise for her to … ”

“Never mind that,” Selby said, “did you tell her not to keep her appointment with me?”

“She asked me if it wouldn’t be inadvisable for her to subject herself to a grueling interrogation after taking an automobile ride of some hundred miles, and I told her that it would.”

“Specifically, what did you find wrong with her?”

“I’m afraid I can’t discuss my patient’s symptoms. A matter of professional privilege, you know, Mr. Selby. But I felt that her health would be benefited by a complete change of scenery.”

“For how long?”

“Until she feels relief from some of the symptoms.”

“And what are the symptoms?”

“General lassitude, nervousness, a severe migraine.”

“What’s migraine?” Selby asked.

“Well, er — a headache.”

“In other words, she had a headache and said she didn’t feel well, so you told her she didn’t need to keep her appointment with me, is that right?”

“That’s putting rather a blunt interpretation on it.”

“I’m cutting out all of the verbal foolishness,” Selby said, “and getting down to brass tacks. That’s the effect of what you told her, isn’t it?”

“Well, of course, it would have that effect and … ”

“Thank you, doctor,” Selby said tersely, “you’ll probably hear more from me about this.”

He dropped the telephone receiver down between the prongs of the desk phone, turned to Trask and said, “The more I see of this, the less I like it.”

Trask pulled down his waistcoat and became coldly dignified.

“Very well,” he said, “if you’re going to adopt that attitude, may I suggest, Mr. Selby, that in the elation of your campaign victory, you have, perhaps, emerged with a swollen concept of your own power and importance?

“As Miss Arden’s manager, I have received advice from the very best legal talent in Los Angeles as to our rights in the matter.

“Frankly, I considered it an arbitrary and high-handed procedure when you telephoned and stated that Miss Arden, a star whose salary per week amounts to more than yours for a year, drop everything and journey to your office. However, since it is her duty as a citizen to co-operate with the authorities, I made no vehement protest.

“The situation was different when it appeared that Miss Arden’s nerves were weakening under the strain, and that her earning capacity might be impaired if she complied with your unwarranted demands upon her time. I, therefore, employed counsel and was advised that, while you have a right to have a subpoena issued for her, compelling her attendance before the grand jury, you have no right to order her to appear for questioning in your office. Incidentally, it may interest you to know that a subpoena, in order to be valid, has to be served in person upon the witness named in the subpoena. I think I need only call to your attention the fact that Miss Arden has virtually unlimited resources at her command, to point out to you how difficult it would be for you to serve such a subpoena upon her. Moreover, she is under no obligation to obey such a subpoena, if to do so would jeopardize her health. You are not a physician. Doctor Cartwright is. His diagnosis of the condition of Miss Arden is entitled to far more weight than your hasty assumption that her headaches and nervous fits are unimportant.”

“I’m sorry to have to talk to you this way, but you asked for it. You’re a district attorney in a rather unimportant, outlying county. If you think you can pick up your telephone and summon high-priced picture stars, who are of international importance, to your city, quite regardless of their own health or personal convenience, you’re mistaken.”

Trask thrust out his jaw belligerently and said, “Have I made myself clear, Mr. Selby?”

Doug Selby stood with his long legs spread apart, hands thrust deep in his trousers pockets. His eyes burned steadily into those of Trask.

“You’re damned right you’ve made yourself clear,” he said. “Now I’ll make myself clear. “I have reason to believe that Miss Arden was in this city, registered in the Madison Hotel under an assumed name. I have reason to believe that a man who was murdered in that hotel called on Miss Arden in her room. I have reason to believe that Miss Arden paid him a large sum of money. Now you can force me to use a subpoena. You may be able to keep me from serving that subpoena. But, by heaven, you can’t keep me from giving out the facts to the press.

“You’re probably right in stating that Miss Arden’s salary per week is greater than mine for a year, but when it comes to a showdown, the ability to dish it out and to take it isn’t measured by salary contracts. I’m just as good a fighter as she is, just as good a fighter as you are — and probably a damned sight better. And you’re going to find it out.

“You’ve done a lot of talking about Miss Arden’s importance, about the fact that she’s an internationally known figure. You’re right in that. That’s the thing that gives you these resources you boast of, the money to hire bodyguards, to arrange for an isolated place of concealment where it would be hard to locate her with a subpoena.

“You overlook, however, that this very fact is also your greatest weakness. The minute the press associations get the idea Miss Arden may be mixed up in this case, they’ll have reporters pouring into town like flies coming to a honey jar. I didn’t want to make any public announcement until I’d given Miss Arden a chance to explain. If she doesn’t want to co-operate with me, that’s her lookout.”

Selby consulted his wrist watch. “It’s twelve minutes past eight. I don’t think Miss Arden’s got to any part of the state where she can’t get here within four hours’ fast driving. I’ll give you until midnight to produce her. If you don’t produce her, I’ll tell the press exactly why I want to talk with her.”

Trask’s face was a wooden mask, but his eyes showed a trace of panic.

“Young man,” he said, “if you did that, you’d be sued for criminal libel and defamation of character, you … ”

“You’re wasting time talking,” Selby said. “If you’re going to get Miss Arden here by midnight, you’d better get started.”

Trask took a deep breath, forced a smile to his face, came toward Selby.

“Now, listen, Mr. Selby,” he said in a conciliatory tone, “perhaps I was a little hasty. After all, you know, our nerves get worn thin in this picture business. Miss Arden’s trip to Madison City was highly confidential, but since you’re interested in it, I think I can explain to you just why she came and … ”

“I don’t want your explanation,” Selby interrupted coldly, “I want hers.”

Trask’s face flushed. “You mean to refuse to listen to what I have to say?”

“At times,” Selby said, “you’re rather good at interpreting the English language.”

Trask fumbled for a cigar in his waistcoat pocket.

“Surely,” he said, “there’s some way in which we can get together. After all … ”

“I’ll be available until midnight,” Selby interrupted. “In the meantime, Mr. Trask, I don’t think I need to detain you.”

“That’s final?” Trask asked, clamping his teeth down on the end of the cigar and giving it a vicious, wrenching motion with his wrist to tear off the end.

“That’s final,” Selby said.

Trask spat out the bit of tobacco as he reached for the doorknob.

“You’ll sing a different tune when we get done with you!” he said, and slammed the door behind him.

Selby called Cushing at the Madison Hotel.

“Cushing,” he said, “I want you to ask all of the regular roomers on the third floor if they heard any typewriting in 321 on Monday night or Tuesday morning. It’ll probably look better if you ask them.”

Cushing said, “This is giving the hotel an awful black eye, Doug. That publicity in The Blade was bad — very bad.”

“Perhaps if you’d kept your mouth shut,” Selby said, “the publicity wouldn’t be so bad.”

“What do you mean?”

“Some of the information must have come from you.”

“Impossible! I didn’t give out any information.”

“You talked to the chief of police,” Selby said. “You know where he stands with The Blade.”

“You mean the chief of police is double-crossing you?”

“I don’t mean anything except that some of the information in the newspaper didn’t come from the sheriff’s office, and didn’t come from mine. You can draw your own conclusions.”

“But he has the right to question me,” Cushing said, “just the same as you have, Doug.”

“All right, then, he’s the one to complain to, not to me.”

“But in your position, can’t you hush the thing up?”

Selby laughed and said, “You can gather just how much chance I have of hushing things up by reading the editorial page in The Blade.”

“Yes,” Cushing said dubiously, “still … ”

“Quit worrying about it,” Selby told him, “and get busy and question your guests on the third floor.”

“I don’t like to question the guests,” he protested.

“Perhaps,” Selby suggested, “you’d prefer to have the sheriff do it.”

“No, no, no; not that!”

“Then suppose you do it.”

Cushing sighed, said, “Very well,” in a tone which contained a complete lack of enthusiasm, and hung up the receiver.

Selby had hardly put the receiver back into place when the phone rang. He picked it up, said “Hello,” and heard a woman’s voice, a voice which was rich, throaty, and intimately cordial.

“Is this Mr. Douglas Selby, the district attorney?”

“Yes.”

“I’m Miss Myrtle Cummings, of Los Angeles, and I have some information which I think you should have. It’s something in relation to the murder case which has been described in the evening newspaper.”

“Can you give it to me over the telephone?” Selby asked.

“No.”

“Well, I’ll be here at my office until midnight,” he said.

There was something hauntingly familiar about the woman’s voice. “I’m sorry,” she said, “but it’s absolutely impossible for me to leave. For reasons which I’ll explain when I see you, I’m confined to my room, but if you could come and see me some time within the next half hour, I think it would be very advantageous for you to do so.”

“Where are you?”

“I’m in room 515 at the Madison Hotel. Do you suppose you could manage to come to my room without attracting any attention?”

“I think so,” he said slowly.

“Could you come right away?”

“I’m waiting for several rather important calls,” he said.

“But I’m sure this is most important,” she insisted.

“Very well,” Selby told her, “I’ll be over within ten minutes.”

He dropped the receiver back into place, put on his overcoat and hat. He closed and locked the office door, but left the light on, so that Rex Brandon would know he expected to return, in case the sheriff should call at the office. He parked his car a couple of blocks from the Madison Hotel.

It was one of those clear, cold nights with a dry wind blowing in from the desert. The stars blazed down with steady brilliance. The northeast wind was surgingly insistent. Selby buttoned his coat, pushed his hands into the deep side pockets and walked with long, swinging strides toward the hotel.

Luck was with him when he entered the hotel. Cushing was not in the lobby. The night clerk was busy with a patron. The elevator operator apparently saw nothing unusual in Selby’s visit.

“Going up to campaign headquarters?” he asked.

Selby nodded.

“Gee, that sure was something, having a murder case right here in the hotel, wasn’t it?” the operator said, as he slid the door closed and started the elevator upward.

Again Selby nodded. “Know anything about it?”

“Just what I’ve heard around the hotel.”

“What did you hear?”

“Nothing, except this guy took the room and was found dead. Cushing says it couldn’t have been a murder. He says it was just a case of accidentally taking the wrong kind of dope and that The Blade is trying to make a big thing of it. The Blade’s had a reporter snooping around here.”

“Chap by the name of Carl Bittner?” Selby asked.

“That’s the one. He’s got the boss sore at him. Cushing thought he was one of your men … and there’s things about the dump that Cushing don’t want printed.”

“What things?” Selby asked.

“Oh, lots of things,” the boy said vaguely. “Take this guy, Trask, for one. Anyone would think he owned the joint. And there’s a room on the fifth floor they never rent. A dame comes and goes on the freight elevator.”

The elevator stopped at the fifth floor.

Selby handed the boy a half dollar. “Thanks for the information,” he said. “I don’t want to be interrupted. I came here because I wanted to get away from telephone calls and people who were trying to interview me. Do you suppose you could forget about taking me up here?”

“Sure,” the operator said, grinning. “I can forget anything for four bits.”

Selby nodded, waited until the cage had started downward before he made the turn in the corridor which took him toward the room at the end of the corridor which they had used as campaign headquarters. When he saw there was no one in the hallway, he tapped gently on the door of 515.

“Come in,” a woman’s voice said. Selby opened the door and stepped into the room.

He knew at once that Shirley Arden had arranged every detail of the meeting with the training which years as an actress had given her.

The door opened into a sitting room. Back of the sitting room was a bedroom. In the bedroom a rose-colored light shed a soft illumination which fell upon the actress’ face in such a way that it turned the dark depths of her eyes into mysterious pools of romance.

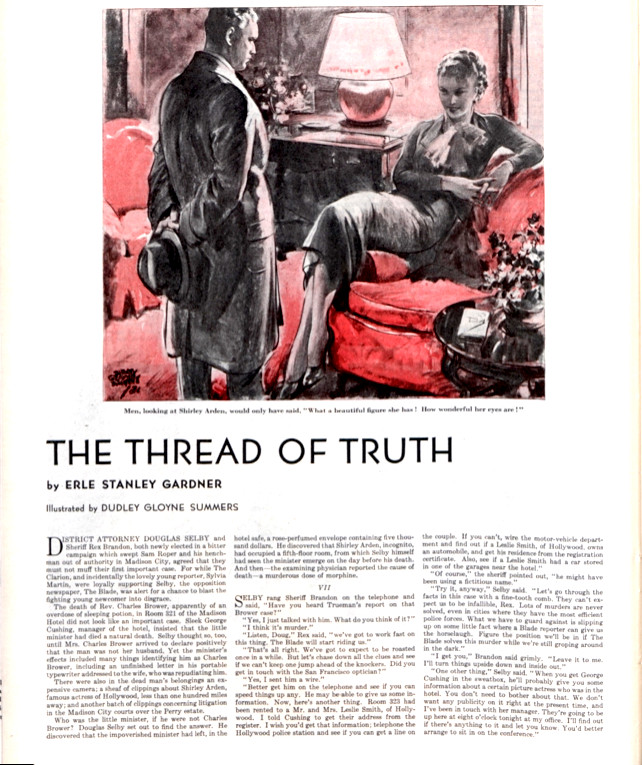

She was attired in a tailored suit of pearl gray. Its simplicity was so severe that it served to center attention upon her face and figure. Had she been ten years older, she would have worn a gown so gorgeously designed that a woman looking at her would have said, “How wonderfully she’s dressed!” But with that pearl gray tailored outfit, men, looking at Shirley Arden, would only have said, “What a beautiful figure she has! How wonderful her eyes are!”

She was seated on the arm of an overstuffed chair, one gray-stockinged leg thrust out at such an angle that the curves caught the eye. Her lips were parted in a smile.

And yet, perhaps as a result of her Hollywood training, she overdid it. Perfect actress that she was, she underestimated the intelligence of the man with whom she was dealing, so that the effect she strove for was lost. Had she remained seated on the arm of the chair just long enough to have given him a glimpse of her loveliness, and then got to her feet to come toward him, he would have been impressed. But her very immobility warned him that the effect had been carefully and studiously planned.

“So,” Selby said, vigorously kicking the door shut behind him, “you were here all the time.”

She didn’t move. Her face was held so that the lighting did not change by so much as a hairline of a shadow. It was as though she had been facing a battery of lights for a close-up.

“Yes,” she said, “I was here. I didn’t want to talk with you unless I had to. I’m afraid Ben Trask didn’t handle the situation very diplomatically.”

“He didn’t,” Selby said. “How about your nerves?”

“I really am very nervous.”

“And,” Selby said, “I suppose the idea was to send Ben Trask over to bluff me. If he’d reported success, then you’d have actually gone into hiding.”

“I didn’t want to take any chances,” she told him. “Can’t you understand? Think what it means to me. Think of my position, my public, my earning capacity. Gossip is a fatal thing to a picture star. I couldn’t afford to have it known I was questioned in connection with the case.

“Ben is a very strong man. He’s always been able to dominate any situation he’s tackled. He makes my contracts for me, and it’s an open secret they’re the best contracts in Hollywood. Then he met you — and failed.”

She waited for the full dramatic value of that statement to manifest itself. Then, with that slow, supple grace which characterizes a stage dancer, she straightened her leg, swung it slowly forward, came to the floor as lightly as thistledown and walked toward him to give him her hand.

“It’s delightful, Mr. Selby,” she said, “to find you so human.”

His fingers barely touched hers. “It depends,” he told her, “on what you mean by being human.”

“I’m certain you’ll listen to reason.”

“I’ll listen to the truth,” he said, “if that’s what you mean.”

“After all, aren’t they the same thing?”

“That depends,” Selby said. “Sit down, I want to talk with you.”

She smiled and said, “I know I’m in your city, Mr. Selby, under your jurisdiction, as it were, but please permit me to be the hostess and ask you to be seated.”

She swept her hand in a gracious gesture of invitation toward the overstuffed chair beneath the floor lamp.

“No,” Selby said, “thank you, I’ll stand.”

A slight frown of annoyance crossed her face, as though her plans were going astray.

Selby stood spread-legged, his overcoat unbuttoned and thrown back, his hands thrust deep into his trousers pockets, his eyes showing just a trace of sardonic humor beneath a grim determination.

“After all,” he said, “I’m doing the questioning. So if anyone is going to sit in that chair beneath the illumination of that light, it’s going to be you. You’re the one who’s being questioned.”

She said defiantly, “Meaning, I suppose, that you think I’m afraid to let you study my facial expressions.”