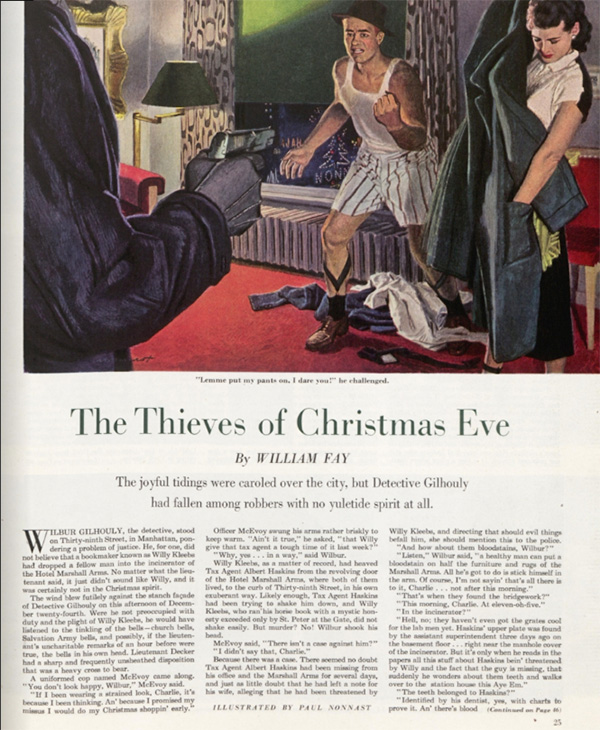

“The Thieves of Christmas Eve” by William Fay

William Fay was a short story writer for the Post in the mid-1900s. His hard-boiled detective stories echo the fashionable trends of noir storytelling. In “The Thieves of Christmas Eve,” detective Wilbur Gilhouly is down on his luck and about to be demoted if he can’t crack a case before Santa is due.

Published on December 24, 1949

Wilbur Gilhouly, the detective, stood on Thirty-ninth Street, in Manhattan, pondering a problem of justice. He, for one, did not believe that a bookmaker known as Willy Kleebs had dropped a fellow man into the incinerator of the Hotel Marshall Arms. No matter what the lieutenant said, it just didn’t sound like Willy, and it was certainly not in the Christmas spirit.

The wind blew futilely against the stanch facade of Detective Gilhouly on this afternoon of December twenty-fourth. Were he not preoccupied with duty and the plight of Willy Kleebs, he would have listened to the tinkling of the bells — church bells, Salvation Army bells, and possibly, if the lieutenant’s uncharitable remarks of an hour before were true, the bells in his own head. Lieutenant Decker had a sharp and frequently unsheathed disposition that was a heavy cross to bear.

A uniformed cop named McEvoy came along. “You don’t look happy, Wilbur,” McEvoy said.

“If I been wearing a strained look, Charlie, it’s because I been thinking. An’ because I promised my missus I would do my Christmas shoppin’ early.”

Officer McEvoy swung his arms rather briskly to keep warm. “Ain’t it true,” he asked, “that Willy give that tax agent a tough time of it last week?”

“Why, yes … in a way,” said Wilbur.

Willy Kleebs, as a matter of record, had heaved Tax Agent Albert Haskins from the revolving door of the Hotel Marshall Arms, where both of them lived, to the curb of Thirty-ninth Street, in his own exuberant way. Likely enough, Tax Agent Haskins had been trying to shake him down, and Willy Kleebs, who ran his horse book with a mystic honesty exceeded only by St. Peter at the Gate, did not shake easily. But murder? No! Wilbur shook his head.

McEvoy said, “There isn’t a case against him?”

“I didn’t say that, Charlie.”

Because there was a case. There seemed no doubt Tax Agent Albert Haskins had been missing from his office and the Marshall Arms for several days, and just as little doubt that he had left a note for his wife, alleging that he had been threatened by Willy Kleebs, and directing that should evil things befall him, she should mention this to the police.

“And how about them bloodstains, Wilbur?”

“Listen,” Wilbur said, “a healthy man can put a bloodstain on half the furniture and rugs of the Marshall Arms. All he’s got to do is stick himself in the arm. Of course, I’m not sayin’ that’s all there is to it, Charlie … not after this morning.”

“That’s when they found the bridgework?”

“This morning, Charlie. At eleven-oh-five.”

“In the incinerator?”

“Hell, no; they haven’t even got the grates cool for the lab men yet. Haskins’ upper plate was found by the assistant superintendent three days ago on the basement floor … right near the manhole cover of the incinerator. But it’s only when he reads in the papers all this stuff about Haskins bein’ threatened by Willy and the fact that the guy is missing, that suddenly he wonders about them teeth and walks over to the station house this Aye Em.”

“The teeth belonged to Haskins?”

“Identified by his dentist, yes, with charts to prove it. An’ there’s blood on the incinerator cover — half washed away, careless like, so that some of it shows up under the glass. Same type as in the apartment, an’ there’s stains in the freight elevator too. It’s the self-service-push-a-button type, you know, and the lieutenant, with his big brain well, naturally, he’s got Willy takin’ the corpse down in the middle of the night — that wouldn’t be too hard — an’ dumpin’ it through the manhole cover. The upper plate? That’s one of them little ironies that murderers have to put up with, the lieutenant says. Mr. Haskins’ upper plate, accordin’ to him, just dropped out unnoticed while Willy was luggin’ the body.”

“Well,” said Officer McEvoy, “I got to shove off, Wilbur. Merry Christmas, if I don’t see ya.”

Wilbur cased the crowd for larceny and lighter mischief with that celebrated eye and memory for faces that had once caused police reporters to refer to him as “Elephant” Gilhouly. Plain-Clothes Man Kaplan, his driver, drove up in the squad car. He was young, unburdened by responsibility, and in possession of a brooch for his girlfriend. It was a lovely item, worth a month’s pay anyhow, and Wilbur reflected, without bitterness, that in his own position, as the loving husband of one and the doting father of four, he had to face the fiscal realities. He had eighty-seven dollars and forty-three cents, and a stern note from a finance company whose kind facilities it had never been his intention to abuse.

“I think maybe I’ll step over to Jablonski’s for a minute,” Wilbur said. “Don’t take any wooden lieutenants; we got one already.”

At Jablonski’s Junior Joyland, Wilbur, on tiptoe, caught the attention of Mr. Jablonski. Mr. Jablonski, who gave a substantial discount to cops and firemen, said, “I got it,” and passed to Wilbur, over people’s heads, $28.74 worth of railroad, in a box — $28.74, that is, with the discount. “What it cost me,” said Mr. Jablonski.

The trains were for little Wilbur, nine. He bought a doll’s house then for his daughter Mavis, a puppet show for Agnes-Mae, and a construction set for Edwin. And then, because — well, because love still beat more strongly in his breast than prudence, he went to a division of Jablonski’s Junior Joyland known as Mommy’s Mart, and made a twenty-two-dollar down payment on a portable, kitchen-size washing machine for Myrtle, his wife, and the one true love of his life. He would call back for the washing machine, he explained to Mr. Jablonski; the other packages he’d take.

“This is a general clearance or you would not of got such bargains,” said Mr. Jablonski. “We will be open till midnight. Come in again; tell your friends.”

Wilbur, with his packages chin-high, moved bravely toward the sidewalk. Jablonski’s, he noted, though a humble establishment, was graced by a better upholstered and more firmly bearded St. Nicholas than most. Wilbur found this somehow reassuring, though his vision was limited. He walked into a mailbox and his packages tumbled. He bent to retrieve them. He heard a mirthless and familiar voice.

“Santa’s li’l’ helper?” someone said.

Well, that was Lieutenant Decker for you. Always the sarcasm, be it Christmas or doomsday.

“What’s your explanation, Gilhouly?”

Wilbur tried to smile. He indicated the packages. “I’m just mindin’ these things for some friends, lieutenant.”

“What friends?”

“Well, my kids,” Wilbur said, then met the other’s cold gaze more steadily. “My kids are my friends,” he said with pride. The truth, after all, was a matter precious to Wilbur.

“You’re a wise guy, Gilhouly?”

“No, sir.” He placed his packages in the squad car.

“Well, Gilhouly,” Lieutenant Decker said. “against my better judgment they set bail for Willy Kleebs. You an’ that judge down at Special Sessions should have your skulls scraped.”

“Yes, sir.”

“You an’ Kleebs was always pretty chummy, Gilhouly. How well did you know him?”

“I’ve known him both in line of duty,” said Wilbur truthfully, “and after hours. I locked him up four times for makin’ book, and he is Agnes-Mae’s godfather. Look, lieutenant, have you checked the guy’s wife?”

“I personally put through the check on the widow, Gilhouly. A fine-type woman. Unimpeachable. A Vassar girl. We had a nice talk about some cultural matters … Take that silly grin off your puss!”

“Yes, sir.”

“Here are your orders, then. Kleebs right now is next door in the Marshall Arms Barbershop for a several-times-over. I want you to watch every place he goes, with regular reports to me. You an’ Kaplan, don’t let him out of your sight! That clear, Gilhouly?”

The lieutenant strode indignantly away. Wilbur and Kaplan moved over to the barbershop window. Willy Kleebs appeared to be taking the full six-dollar treatment in the No. 1 chair. He waved gaily to Wilbur and Kaplan.

“He never dropped nobody into no oven,” Wilbur said.

“Howja do at Jablonski’s, Wilbur?” Kaplan asked. “Any good?”

“Take a look for yourself. There’s nothin’ like havin’ a family, my boy. Take a look in the back of the car.”

In the No. 1 chair, Willy Kleebs wore a look of deep content. Good old Willy, always smiling — good times, bad times, always the same old Willy. Kaplan called to Wilbur from the curb.

“You put them in the back of the car? What car?”

“Right there. In the back.” He walked over to the car, looked in. The back of the car was empty.

“They ain’t here,” Plain-Clothes Man Kaplan said.

Wilbur smiled weakly. It was a joke. I’m laughing, Wilbur thought. But the brutal truth prevailed.

“Gone,” said Kaplan. “Like I toldja.”

“Eighty-one dollars,” Wilbur said. His senses reeled. Jablonski’s Santa Claus kept ringing his bell and chewing his gum. Wilbur, a tall man, turned dismayed eyes on the multitude. He saw no one sprinting through traffic with a doll’s house and assorted lumps of joy. He wanted to cry. This was Gilhouly, the good provider, with six dollars and some cents remaining, and a week late with the finance company. This was Gilhouly, the —

“Wil-bur-r-r!” Kaplan called from the plate-glass window of the barbershop. Wilbur walked over. “Look,” said Kaplan.

The No. 1 barber chair was empty. Willy Kleebs was gone.

…

It was not easy in the station house to stand before your fellow officers while Lieutenant Decker peeled your dignity away — artfully and easily, like the skin of a scalded peach.

“I always knew you were a whale of a fellow, Gilhouly,” the lieutenant said. “I could tell it by the blubber in your head.”

Less loyal comrades snickered; others looked away. The lieutenant was in the process of enjoying himself.

“I would say, Gilhouly, that it’s gonna be strictly brass buttons an’ blue coat from here in. Staten Island, maybe, or the Bronx frontier, where we can push you inta Yonkers.”

Wilbur dropped his eyes. You took it, that was all. He could remember the last time he’d been threatened with a return to uniform. His wife had stemmed her tears. “Wilbur,” she had said with priceless loyalty, “you look beautiful in blue.”

Early-winter’s darkness was over the town as Wilbur left the station house with Kaplan. Lights were everywhere, though it was only five o’clock. They came to where the squad car still stood parked before Jablonski’s.

Wilbur was watching Jablonski’s Santa Claus, whose face he had not had a chance to view at leisure until now. He stepped closer, examining minutely, and with small attempt at politeness, Santa’s rosy cheeks. Into operation came the old Gilhouly intuition. Wilbur moved and Santa jumped. Wilbur caught old Santa by the beard.

“Legomme!” Santa shouted.

But Wilbur clung tenaciously. He pulled the beard the length of the elastic, then let it snap.

Old Santa howled. “Legomme! Cudditout!”

It was not really Santa. It was a man named Mutuel Minskoff, who worked for Willy Kleebs. “What I thought,” said Wilbur.

Mutuel Minskoff was a bookmaker’s runner, which is no kind of Santa Claus at all, but one who takes bets on horses. Wilbur shook Jablonski’s Santa Claus.

“Where’s Willy Kleebs?” he demanded. “Where’s them packages you stole out of the car?”

“Honest, Wilbur — honesta me mother’s grave, I don’t know what you’re sayin’!”

Wilbur, with Kaplan’s assistance, pushed Mutuel Minskoff into the car. Wilbur stretched the beard’s elastic its full, intimidating length. “You gonna tell me?”

“We have little or nothing to say to one another,” Mutuel said with dignity, “except that I don’t like your attitude.”

Wilbur let the beard snap. He was not a man disposed toward cruel means of persuasion, but he was nonetheless determined.

“Let’s get it straight, Minskoff,” Wilbur said. “A fifty-dollar-per-diem wise guy like yourself don’t become a ten-dollar St. Nicholas because he likes to get stuck in chimneys. Well, do you?”

“This is our slack season, Wilbur.”

“Never mind that. Where is Willy Kleebs?”

“He went to visit his ninety-three-year-old mother in the Bronx.”

“Where’bouts in the Bronx?”

“That’s one of those things Willy has always kept to himself,” said Mutuel Minskoff, “an’ the little old lady don’t know he’s in trouble with the cops, you understand? In fact, she thinks that Willy’s in the feed-an’-grain trade.”

“You’re lyin’, Minskoff,” Wilbur said, but he did not really believe the man was lying. It sounded like Willy, all right. He restrained Plain-Clothes Man Kaplan from snapping the beard again. “I’m asking you, Mutuel, Number One — who stole my packages? I am asking you, Number Two — why you been standing all day in front of Jablonski’s making like an elk driver?”

“As for the packages, Wilbur, believe me, I dunno. As for Point Number Two, I’ve been watchin’ for Tax Agent Haskins. Willy didn’t kill ’im. I been waitin’ here for Haskins because we know he’s got to come back.”

“Come back for what?”

“Haskins made one mistake, Wilbur. Just like he dropped his upper plate next to the incinerator on purpose, he also drops somethin’ else in Willy’s suite, but not on purpose.”

“What did he drop?”

“He dropped his safe-deposit-box keys, Wilbur. A whole ring o’ them, he dropped. You get it? Haskins is a crook. An’ where does a crook with a big wad o’ dough an’ a small pay check hide this embarrassin’ disparity of means? In safe-deposit boxes, don’t he? In eight different banks, under eight different names.”

“You know this? You’re not lyin’ to me, Minskoff?”

“Here,” said Mutuel Minskoff, “are the keys. Understand, they’ve just got numbers on them an’ we don’t know what banks, an’ we don’t know what names this guy is usin’. All we know is he has got to get them keys.”

“Why didn’t Willy come to the police with these?”

“Willy sees that with Decker on the case, an’ blabbin’ like he does, there might be talk in the papers the cops have got a certain set of keys, an’ this Haskins will just take off like a bluebird. Willy would like to catch Haskins himself. Willy is an honest man what pays his taxes, but this guy not only tries to shake ‘im down, he owes ’im maybe twenty grand on horse bets.”

“Tell more, Mutuel. Tell all.”

“Well, Wilbur, we figured that Haskins, the crook, wanted to lam for liberty before the tax department caught on to the size of his personal assets. So what’s a better way to get off with a bundle o’ dough an’ not be tailed than to have yourself declared murdered? That’s why he sets up this frame about Willy, an’ why your friend, the lieutenant, begins to drool about maybe he can have Willy measured for that warm chair up in Ossining. You get it?”

“It happens also to have been my personal theory,” said Wilbur modestly. “Except, of course, I never knew about the keys. You better hand ’em over to me like a good boy, Mutuel. Thass right. Now get back on the job; keep ringin’ that bell … And, Kaplan,” he said, “you keep an eye on Santa.”

This was Gilhouly, the hound of justice, on the scent. The Hotel Marshall Arms, set in the shopping district of New York, was vast, commercial, and of wholesome reputation. In the plaza, as he entered, Wilbur rejoiced at the Christmas tree that rose gigantically for several floors — its glowing lights bespeaking warmth and good cheer in a cold and unbelieving world. Willy Kleebs’ suite, where Wilbur thought a little look around might help, was on the seventh floor.

“Where’s the cop they had watchin’ this suite?” he asked the bellhop who let him in by means of a key.

“The lieutenant said there was no pernt to it,” the bellhop reported. “The lieutenant sent ’im after bundle snatchers.” The bellhop, with a taste for police procedure, hovered.

“Blow,” said Wilbur. “Get lost, sonny.”

Wilbur closed the door behind him and was immediately aware of another’s presence. A woman wearing an apron and a somewhat guilty look was dusting, or at least appeared to be dusting, in the sitting room. “This place is under surveillance,” Wilbur said. “Who are you?”

“Why, Mr. Kleebs always lets me have a key to do the cleaning,” the lady said. Her apron was ruffled and unspotted. She had a way of placing hands on hips that bespoke some gayer setting and invoked old memories of action that had nothing to do with dustpans. She looked more like a cupcake to Wilbur than she looked like somebody’s mother rubbing honest knuckles raw. “If you’ll excuse me — ”

“One minute,” Wilbur said. The files of his memory were opening. “Hold on, lady.” He could smell clams, somehow. Why clams? Coney Island? No, it wasn’t Coney Island. Brighton Beach? Not Brighton either. Then it snapped. It came to him. “Hello, Kitty,” Wilbur said.

“I beg your pardon?”

“Gypsy Kitty Klein, from Rockaway Park. Used to tell fortunes for a thief named Hennessey. Must be fifteen years since I locked ’im up. You lookin’ for something, Kitty?”

“Officer,” said Gypsy Kitty, “you are playing the wrong trombone. Now, if you don’t mind — ”

“Lookin’ for some safe-deposit-box keys, Kitty?” Wilbur was swinging in the dark, but batting rather well. The proper button had been pressed. “You couldn’t by any chance be Mrs. Albert Haskins, could you? The Vassar girl? The little widow who had the nice cultural chat with the lieutenant?”

“As a matter of fact, I was really only — ”

“Don’t apologize, an’ don’t get excited, Kitty, because — well, about those keys; Homicide ain’t even heard o’ them. Me, Gilhouly; I got the keys, an — ”

“Don’t move, Gilhouly! Stay where you are!” The voice was authoritative. Wilbur did not move. Albert Haskins, with a .38 revolver, spoke distinctly, even minus his upper plate. Wilbur did not move, because his own gun lay deep in the cold-weather bunting he had neglected to unbutton. “Hands higher, Gilhouly … Frisk him, Katherine,” said Haskins to the cupcake.

Mrs. Haskins unbuttoned Wilbur’s winter ulster and rapidly divested him of firearms. She went through his jacket and its inner pockets, searching for the safe-deposit keys, without first having cased the crumpled overcoat that lay on the floor.

“Take off your jacket,” Haskins ordered. “Now your shirt.” Haskins waved his revolver convincingly. “Your pants, Gilhouly!” he commanded.

Wilbur, standing in his underwear, said, “This has gone far enough!” He said this just as Mrs. Haskins, retrieving his coat from the floor, shook it lightly once or twice and heard the jingle of keys. This was defeat, abject and full.

“Look out in the hall,” Haskins said to his synthetic widow. Gypsy Kitty gaped out, then motioned all was clear. Albert Haskins put the cool hard metal of his .38 against the warm hard head of Detective Gilhouly and escorted him uncompromisingly along the empty corridor, while Mrs. Haskins flipped a key in the lock of a door marked PORTER. Wilbur, about to spring into desperate action, went quietly to slumberland as something crashed against his head.

I am dead, thought Wilbur; dead in the chill grave. He heard somebody groaning next to him. I am here, he corrected himself, in the porter’s room, and in my underwear, but I am not alone. He rose unsteadily and stood in heavy darkness that was not illumined by the flashes that kept going off in his skull. He found a switch and snapped it on. At his feet lay Mutuel Minskoff in his Santa Claus suit, beard and all. Wilbur tried the door, but it would not yield. He looked about for some suitable means to persuade it. He looked, as well, at Santa.

In the street, by now, Plain-Clothes Man Kaplan was confused. Bitterly he reflected you could trust nobody — not even Santa Claus or your esteemed good friend, Gilhouly. That Minskoff, in particular, had shattered solemn trust, the dog, but here Plain-Clothes Man Kaplan paused. It seemed to him that he saw Minskoff now race wildly through the plaza of the Hotel Marshall Arms, arms waving, shouting.

“The hell ya do!” Plain-Clothes Man Kaplan said. He interfered with Santa’s headlong haste. He teed off with his strong right arm and pulled off Old Santa’s beard. Old Santa tripped and looked up from the pavement, short of cheer.

“That’s a nice thing to do,” said Wilbur Gilhouly. “A nice way, Kaplan, I must say, to implement the law.”

The lieutenant postulated. He asked, of all who were there to listen, the one seemingly relevant question: “How crazy can you get?” And, Wilbur, beardless, but in his red-and-ermine suit, seemed a fairly apt reply.

“Albert Haskins is alive,” Wilbur repeated. He had stated this without compromise at least one hundred times. “I seen him. He hit me in back of the head. He locked me in a room. Him an’ his wife. She used to be known as Gypsy Kitty Kl — ”

“My dear Gilhouly,” the lieutenant interrupted, “did you see all these interesting things before or after you got slugged in the head? Did Kaplan see Haskins? … Did you, Kaplan?”

“No, sir,” Kaplan was obliged to say, but he was sorry for Wilbur. “All I seen was this Mutuel Minskoff.”

“And where is Minskoff?”

“Like I said before,” said Wilbur, “he was with me in the porter’s room. I had no clothes on and — All right laugh; laugh, all of you! So I had no clothes on, an’ I had to get out of there. I don’t know what happened to Mutuel after that. I took his suit an’ I — ”

“Gilhouly!” the lieutenant said with sudden fierceness. “How much in cash did Minskoff and Willy Kleebs pay you to concoct this story?”

Wilbur leaped to his feet in anger. His doubled fists and squared jaw made Lieutenant Decker blanch. Inspector Gerhardt, until now quietly sitting by, at this point intervened.

“That will be enough for now, lieutenant,” the inspector said. “I happen to know Gilhouly’s record.” A kindly man, he walked over and examined the back of Wilbur’s head. “A severe blow of this kind can induce all kinds of impressions in a man’s mind,” the inspector said. “Don’t try to think now, Gilhouly. After all, we just now combed the hotel with a flock of cops. We’ve got men in the lobby and at the rear and side exits. The trouble is, Gilhouly, that your story’s not standing up. There’s no sign of Haskins, if he’s alive, and there is no sign of Minskoff. There is nothing in our available files — well, tonight, at least — to support what you say about Mrs. Haskins’ past record. Are you suffering from any personal troubles, Gilhouly?”

“No, sir.” He glanced at the clock. He shrugged. He smiled resignedly. “Three hours to Christmas, an’ I’m supposed to be home by now … You mind if I phone my wife?” he asked. “It’s only a nickel call.

“ … Merry Christmas, darling!” Myrtle said. “Whatever’s been keeping you? … You’re what, dear?”

“All loused up,” said Wilbur. “I thought I oughta tell you I am strictly a crushed cornucopia, baby … Somebody swiped the packages … You what? You ain’t sore? … An’ I can’t get away just now; it seems — ”

“I will be right down,” Mrs. Gilhouly said. “I will be right down in a half hour, Wilbur, to meet you. Don’t you worry … The children? Well, your sister Marge is here.”

Wilbur and Kaplan sat alone in the room. Time passed. There would be further questioning, the inspector had said, when he was able to piece all the claims and counterclaims together, but there did not seem much sense in keeping eight men at the Marshall Arms much longer in pursuit of the unestablished ashes or person of Albert Haskins. Not tonight, of all nights. There was, to be sure, an emergency call from the Hotel Marshall Arms, but it did not concern the detective bureau. The lights of the giant Christmas tree had been shorted; there had been sparks. There was always the hazard of fire.

Wilbur walked to the window and looked up at the star. “Kappy,” he said, “do you believe in miracles?”

“Yes,” said Kaplan; “from now on, anyhow. Turn around, Wilbur. Turn around slowly.”

Wilbur turned. He saw. framed in the wide door of the room, Tax Agent Albert Haskins. Mr. Haskins was in the safekeeping of the emergency squad. Inspector Gerhardt stood with them.

“This,” said the inspector, “is what shorted the circuit on the Christmas tree. It seems he jumped into it from a third-floor window when all those cops were arriving to check on Wilbur’s story. His idea was to cover himself with decorations, then climb down later, I guess, but it got cold up there and he must have been stamping his feet. Anyhow, he blew the lights and put a nice shock into himself. It wasn’t till the lights came on again that the boys could see him hangin’ there like a peppermint stick. We thought maybe you would like to drop him in the lieutenant’s stocking, Gilhouly.”

Wilbur approached Tax Agent Haskins without malice. He touched the lump behind his ear, and then touched Mr. Haskins, to be sure that he was real. He wasn’t even mad at the lieutenant.

“As for small details,” the inspector said a little later, “we can attend to them in due time. We’re picking up Mrs. Haskins and a porter who was in cahoots with them. You were right, Gilhouly, from the beginning, but the way I figure it, tonight a family man’s got things to do.”

It was a clear night. It was cold and framed in beauty. There were lights in the sky and in the Marshall Arms Hotel and in Jablonski’s Junior Joyland. Mr. Jablonski himself stood on the curb with Willy Kleebs.

“Merry Christmas,” said Willy, “to you and yours, Wilbur, from me an’ my ol’ lady … Good evenin’, Mrs. Gilhouly.

Out of the shadows now, wearing a borrowed overcoat above a porter’s uniform that fitted him like a green banana; Mutuel Minskoff emerged.

“I never deserted ya, Wilbur,” Mutuel said. “Willy came back and I told him you were in trouble, an’ when we got here, there’s this Haskins, like a two-legged mistletoe, hangin’ from the tree. We forgot to kiss ’im.”

“Excuse me,” said Mr. Jablonski, “but if you will kindly look in the car, Mr. Gilhouly. A doll’s house, a puppet show, a construction set and electric trains yet. And on the side of the car, Mrs. Gilhouly, tied like a moose, a washing machine … except it is the full-size model, not the portable, mind you.”

Wilbur stammered. Wilbur tried to protest. “Look, boys, it’s sweet, but I can’t be bribed. You must understand it.”

“At Jablonski’s Joyland,” said Mr. Jablonski, “it’s a general clearance, and besides, I just got paid by a certain party. And what is more, Gilhouly, the inspector knows about it. He says you should kindly shaddup your face while Kaplan drives you home.”

The bells in the church were tolling as Kaplan started the car. They tolled the rich, good message of two thousand years, and Wilbur’s heart was full. Mrs. Gilhouly, a bit snug in the front seat with Plain-Clothes Man Kaplan and her husband, reached for Wilbur’s hand. “I wonder where,” she said, “at this hour, dear, we could find you another beard.”

Featured image: Illustration by Paul Nonnast (©SEPS)

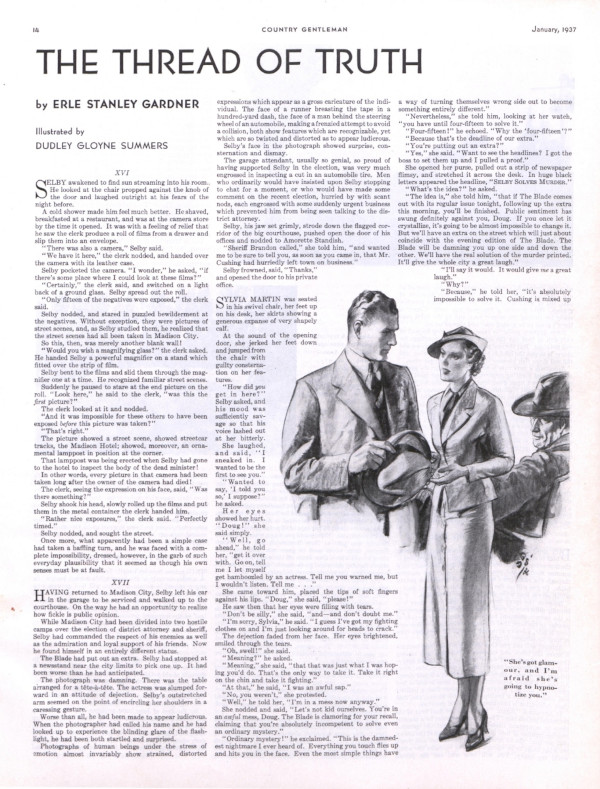

“The Thread of Truth, Conclusion” by Erle Stanley Gardner

When he died, in 1970, Erle Stanley Gardner was the best-selling American fiction author of the century. His detective stories sold all over the globe, especially those with his most famous defense attorney protagonist, Perry Mason. His no-nonsense prose and neat, satisfying endings delighted detective fans for decades. Gardner wrote several stories that were serialized in the Post. In Country Gentleman, his 1936 serial “The Thread of Truth” follows a fresh D.A. in a clergyman murder case that comes on his first day on the job.

Published on January 1, 1937

XVI

Selby awakened to find sun streaming into his room. He looked at the chair propped against the knob of the door and laughed outright at his fears of the night before.

A cold shower made him feel much better. He shaved, breakfasted at a restaurant, and was at the camera store by the time it opened. It was with a feeling of relief that he saw the clerk produce a roll of films from a drawer and slip them into an envelope.

“There was also a camera,” Selby said.

“We have it here,” the clerk nodded, and handed over the camera with its leather case.

Selby pocketed the camera. “I wonder,” he asked, “if there’s some place where I could look at these films?”

“Certainly,” the clerk said, and switched on a light back of a ground glass. Selby spread out the roll.

“Only fifteen of the negatives were exposed,” the clerk said.

Selby nodded, and stared in puzzled bewilderment at the negatives. Without exception, they were pictures of street scenes, and, as Selby studied them, he realized that the street scenes had all been taken in Madison City.

So this, then, was merely another blank wall!

“Would you wish a magnifying glass?” the clerk asked. He handed Selby a powerful magnifier on a stand which fitted over the strip of film.

Selby bent to the films and slid them through the magnifier one at a time. He recognized familiar street scenes.

Suddenly he paused to stare at the end picture on the roll. “Look here,” he said to the clerk, “was this the first picture?”

The clerk looked at it and nodded.

“And it was impossible for these others to have been exposed before this picture was taken?”

“That’s right.”

The picture showed a street scene, showed streetcar tracks, the Madison Hotel; showed, moreover, an ornamental lamppost in position at the corner.

That lamppost was being erected when Selby had gone to the hotel to inspect the body of the dead minister!

In other words, every picture in that camera had been taken long after the owner of the camera had died!

The clerk, seeing the expression on his face, said, “Was there something?”

Selby shook his head, slowly rolled up the films and put them in the metal container the clerk handed him.

“Rather nice exposures,” the clerk said. “Perfectly timed.”

Selby nodded, and sought the street.

Once more, what apparently had been a simple case had taken a baffling turn, and he was faced with a complete impossibility, dressed, however, in the garb of such everyday plausibility that it seemed as though his own senses must be at fault.

XVII

Having returned to Madison City, Selby left his car in the garage to be serviced and walked up to the courthouse. On the way he had an opportunity to realize how fickle is public opinion.

While Madison City had been divided into two hostile camps over the election of district attorney and sheriff, Selby had commanded the respect of his enemies as well as the admiration and loyal support of his friends. Now he found himself in an entirely different status.

The Blade had put out an extra. Selby had stopped at a newsstand near the city limits to pick one up. It had been worse than he had anticipated.

The photograph was damning. There was the table arranged for a tete-a-tete. The actress was slumped forward in an attitude of dejection. Selby’s outstretched arm seemed on the point of encircling her shoulders in a caressing gesture.

Worse than all, he had been made to appear ludicrous. When the photographer had called his name and he had looked up to experience the blinding glare of the flashlight, he had been both startled and surprised.

Photographs of human beings under the stress of motion almost invariably show strained, distorted expressions which appear as a gross caricature of the individual. The face of a runner breasting the tape in a hundred-yard dash, the face of a man behind the steering wheel of an automobile, making a frenzied attempt to avoid a collision, both show features which are recognizable, yet which are so twisted and distorted as to appear ludicrous.

Selby’s face in the photograph showed surprise, consternation and dismay.

The garage attendant, usually so genial, so proud of having supported Selby in the election, was very much engrossed in inspecting a cut in an automobile tire. Men who ordinarily would have insisted upon Selby stopping to chat for a moment, or who would have made some comment on the recent election, hurried by with scant nods, each engrossed with some suddenly urgent business which prevented him from being seen talking to the district attorney.

Selby, his jaw set grimly, strode down the flagged corridor of the big courthouse, pushed open the door of his offices and nodded to Amorette Standish.

“Sheriff Brandon called,” she told him, “and wanted me to be sure to tell you, as soon as you came in, that Mr. Cushing had hurriedly left town on business.”

Selby frowned, said, “Thanks,” and opened the door to his private office.

Sylvia Martin was seated in his swivel chair, her feet up on his desk, her skirts showing a generous expanse of very shapely calf.

At the sound of the opening door, she jerked her feet down and jumped from the chair with guilty consternation on her features.

“How did you get in here?” Selby asked, and his mood was sufficiently savage so that his voice lashed out at her bitterly.

She laughed, and said, “I sneaked in. I wanted to be the first to see you.”

“Wanted to say, ‘I told you so,’ I suppose?” he asked.

Her eyes showed her hurt. “Doug!” she said simply.

“Well, go ahead,” he told her, “get it over with. Go on, tell me I let myself get bamboozled by an actress. Tell me you warned me, but I wouldn’t listen. Tell me … ”

She came toward him, placed the tips of soft fingers against his lips. “Doug,” she said, “please!”

He saw then that her eyes were filling with tears.

“Don’t be silly,” she said, “and — and don’t doubt me.”

“I’m sorry, Sylvia,” he said. “I guess I’ve got my fighting clothes on and I’m just looking around for heads to crack.”

The dejection faded from her face. Her eyes brightened, smiled through the tears.

“Oh, swell!” she said.

“Meaning?” he asked.

“Meaning,” she said, “that that was just what I was hoping you’d do. That’s the only way to take it. Take it right on the chin and take it fighting.”

“At that,” he said, “I was an awful sap.”

“No, you weren’t,” she protested.

“Well,” he told her, “I’m in a mess now anyway.”

She nodded and said, “Let’s not kid ourselves. You’re in an awful mess, Doug. The Blade is clamoring for your recall, claiming that you’re absolutely incompetent to solve even an ordinary mystery.”

“Ordinary mystery!” he exclaimed. “This is the damnedest nightmare I ever heard of. Everything you touch flies up and hits you in the face. Even the most simple things have a way of turning themselves wrong side out to become something entirely different.”

“Nevertheless,” she told him, looking at her watch, “you have until four-fifteen to solve it.”

“Four-fifteen!” he echoed. “Why the ‘four-fifteen’?”

“Because that’s the deadline of our extra.”

“You’re putting out an extra?”

“Yes,” she said. “Want to see the headlines? I got the boss to set them up and I pulled a proof.” She opened her purse, pulled out a strip of newspaper flimsy, and stretched it across the desk. In huge black letters appeared the headline, “SELBY SOLVES MURDER.”

“What’s the idea?” he asked.

“The idea is,” she told him, “that if The Blade comes out with its regular issue tonight, following up the extra this morning, you’ll be finished. Public sentiment has swung definitely against you, Doug. If you once let it crystallize, it’s going to be almost impossible to change it. But we’ll have an extra on the street which will just about coincide with the evening edition of The Blade. The Blade will be damning you up one side and down the other. We’ll have the real solution of the murder printed. It’ll give the whole city a great laugh.”

“I’ll say it would. It would give me a great laugh.”

“Why?”

“Because,” he told her, “it’s absolutely impossible to solve it. Cushing is mixed up in it, and Cushing’s skipped out. The actress is mixed up in it, heaven knows how deeply, and she won’t talk. She’ll avoid service of a subpoena. Probably she’s taking a plane right now, flying to some seaport where she can take a trip for her health.

“Charles Brower probably knows something about her, but Sam Roper’s had him released on habeas corpus. We didn’t have enough to put a charge against him. He merely claimed the five thousand dollars belonged to him. For all we know, it does. In trying to secure possession of it, he may have been seeking to secure possession of his own property. He merely refuses to state where the money came from or how it happened to be in the possession of the dead man. He claims it’s a business matter which doesn’t concern us. That’s no crime. And as long as Sam Roper is his lawyer, he won’t talk. Eventually, we’ll get the low-down on him, but it’ll take lots of time. Even then, it’ll be guesswork. What we need is proof.

“If I try to link Shirley Arden with that murder, either directly or indirectly, I’ll be fighting the interests of some of the biggest bankers and financiers in the country. I’ll be bucking politicians who have not only a state but a national influence. And I’ll be advertising myself as a sucker. The thing’s got to be fought out by a slow, dogged, persistent campaign.”

She was standing close to him. Suddenly she reached up and shook him.

“Oh, you make me so darned mad!” she exclaimed.

“What’s the matter?” he asked.

“Looking at it that way,” she told him, “by the time you’ve worked out a solution of the mystery no one will care anything about it. You probably won’t be in office. They’re going to start circulating a recall petition against you tomorrow morning. Everyone in the city feels you either sold out or were made a fool of. The minute you let it be known you’re trying to locate Shirley Arden, after having had that little dinner scene with her last night, and particularly when it becomes known that you can’t find her, you’re finished. It doesn’t make any difference how many murder mysteries you solve.

“And don’t ever underestimate this Carl Bittner. He’s clever. He’s a newspaper man who knows all of the angles. He knows how to use propaganda and sway public sentiment. While you’re patiently solving this mystery step by step, Bittner will take some shortcut and you’ll read the solution spread all over the front page of The Blade.”

“All right,” Selby said, grinning, “you win. We solve the murder by four-thirty.”

“Four-fifteen,” she said. “In fact, the solution has to be a little earlier, so I can get the highlights of the story telephoned over to the office.”

“When do we start?” he asked her, grinning.

“We start now.”

“All right,” he said, “here’s something for you to consider: Here’s the camera which the dead man had in his possession. For some reason or other, that camera seems to have a very peculiar significance. Someone tried to steal it from me in Hollywood last night.”

“Because of the films which were in the camera?” she asked, her eyes showing her excitement.

“I wouldn’t say so,” he said. “The films in the camera show a very fine assortment of street scenes. In fact, they show the main streets of Madison City.”

“But there may be something on them. There may be something significant we could catch, something which will show the purpose he had in coming here.”

“There is,” he told her grimly; “there’s something very significant on them.”

“What is it?”

“The new ornamental street-lighting pole at the corner in front of the Madison Hotel. That pole was being put up Tuesday morning when I drove down to the hotel after the body had been discovered. In other words, the pictures in that camera were taken anywhere from hours to days after the man was killed.”

“But how could that have happened?”

He shrugged his shoulders.

“The camera was in the suitcase when you went to the hotel?”

“Yes.”

“Then the films must have been substituted.”

“How?”

“What happened to the camera?”

“The coroner took it and kept it in his safe.”

“But someone might have substituted films.”

He laughed and told her, “That’s pretty much of a job. It would take some time. You see, these films aren’t the ordinary type of roll films. They’re not backed with black paper and … ”

He broke off suddenly, to stare moodily at her and said, “So that’s it.”

“What?” she asked.

“Rogue being poisoned.”

“What about him?”

“That’s the coroner’s dog, a big police dog who watches the place. Someone poisoned him. The poison was cunningly concealed and placed in half a dozen different places.”

“Oh, yes, I remember. I didn’t know his name was Rogue.”

“That was yesterday. Shortly after we came back from Riverbend.”

“And the poisoning was successful?”

“I don’t know whether the dog died or not, but he had to be removed to the veterinary hospital.”

“Then that was done so someone could substitute the films.”

Selby said, “If that’s true, it was fast work, because I picked up the camera right afterwards.”

“But the coroner was very much attached to his dog, wasn’t he?”

“Yes.”

“And he was down at the veterinary’s, trying to see whether the treatment would be successful?”

“Yes.”

“Then that’s it,” she explained. “The films must have been substituted while he was down there. You can fix that time within very narrow limits. It probably won’t be over half an hour all together.”

Selby nodded and said, “That’s a thought. How does the sheriff stand on this thing?”

“You mean about the piece in The Blade?”

“Yes.”

“I don’t know,” she said. “Of course, he has his own political future to think of.”

“I’m just wondering.” Selby said. “No, I’m not either. The mere fact that I think I’m wondering shows how warped my mental perspective is. Rex Brandon isn’t the type who would throw me over. He’ll stick.”

As though he had taken his cue from the words, Sheriff Brandon opened the door of Selby’s private office and said, “Hello, folks, I’m walking in unannounced.”

His big black sombrero was tipped back on his head. A homemade cigarette dangled from a corner of his mouth. His face showed the lines of character emphasized as he twisted his mouth in a one-sided grin.

“Well, old son,” he said, “it looks as though we’ve put our foot in it, doesn’t it?”

Selby said, “Where do you get that ‘we’ stuff? I’m the one that’s in bad. You’re sitting pretty. Go ahead and watch your own political fences, Rex; don’t get tied up with me. I’m a political leper.”

The sheriff’s face showed genuine surprise.

“I never expected to hear you talk that way,” he said.

“What way?”

“Turning against a partner.”

“You mean I’m turning against you,” Selby demanded incredulously, “because I won’t let you share in my disgrace?”

“Well, I wouldn’t exactly put it that way,” the sheriff said, “but we’re in this thing together and, somehow, it don’t look right for you to … well, to figure there’s any question about where I stand.”

Sylvia Martin took down the telephone and said, “Get me the city editor of The Clarion … Hello, this is Sylvia; change that headline to read ‘SELBY AND BRANDON SOLVE MURDER.’ … Yes, I’m on the inside of the story now. It’s all ready to break. They’ve got the real murderer all tied up. They’re just perfecting their case now before they strike. The arrest will be about three-thirty or four o’clock this afternoon. We’ve got an exclusive on it. I’ll have the story all ready so I can telephone it in … No, I’m not going to give you the story now … No, it isn’t all bluff … Yes, I know I’m staking my job on it … All right; goodbye.” She slammed the receiver back into place.

Selby looked at her moodily and said, “So your job hangs on it too, does it?”

“Sure,” she said cheerfully.

Selby pulled the films from his pocket.

“Well, Sheriff,” he said, “here’s about all I’ve done. I’ve got a beautiful assortment of photographs of the main streets of Madison City.”

“Those were the films that were in the camera?”

“Yes. And those films were taken long after the man was dead.”

“What?”

“It’s a fact.”

“We were discussing,” Sylvia said, “how the films could have been switched in the camera. We’ve about decided that when the coroner’s dog was poisoned, it was because someone wanted to switch films.”

“What time was the dog poisoned?” Brandon asked.

“Well,” Selby said, “we can soon find out about that.”

He reached for the telephone, but it was ringing before his fingers touched it.

He picked up the receiver, said, “Hello,” and heard Shirley Arden’s penitent voice.

“Douglas Sel — ” she asked; “I mean, Mr. Selby?”

“Yes,” he said, stiffening.

“I’m over at the hotel,” she told him. “Strictly incognito. The same room 515.”

“What kind of a run-around is this?” he demanded. “You certainly gave me enough of a double-cross last night. If you want to know the details, you can pick up a copy of The Blade.”

“Yes,” she said contritely, “I’ve already seen it. Please come over.”

“When?”

“Right away.”

“All right,” Selby said grimly, “I’m coming. And I’m not going to be played for a sucker this time either.”

He slammed up the telephone.

Sylvia Martin was looking at him with wide, apprehensive eyes.

“Shirley Arden?” she asked.

He nodded.

“You’re going, Doug?”

“Yes.”

“Please don’t.”

“Why?”

“I don’t know. I just don’t trust her. She’s clever. She’s an actress. She’s got glamour, and I’m afraid she’s going to hypnotize you.”

“She’s not going to hypnotize me this time,” Selby promised.

“Oh, please, Doug. You stay away. Have Sheriff Brandon serve a subpoena on her to appear before the grand jury. It’s your one chance to show that you weren’t bribed. This may be a trap, and, even if it isn’t, suppose Bittner finds out about her being there and about you going over? Can’t you see what we’re fighting for? We’re working against time and it means so much — so much to all of us.”

He shook his head doggedly and said, “I promised I was going, I’m going to go. I owe that much to my self-respect. She called me in confidence, and I’ll see what she has to say before I betray that confidence.”

Selby started for the door. He looked back, to see Sylvia Martin’s pleading eyes, then he closed the door.

XVIII

Doug Selby knocked at the door of 515; then, without waiting for an answer, pushed the door open.

Doug Selby knocked at the door of 515; then, without waiting for an answer, pushed the door open.

Shirley Arden was coming toward him. She was alone in the room.

He closed the door behind him, stood staring at her.

She came close to him, put her hands on his shoulders. Eyes which had thrilled millions of picture fans stared into his with compelling power.

“Am I forgiven?” she asked.

“That depends,” he told her.

“Depends on what?”

“Depends on what you say and how you say it.”

“What do you want me to say?” she asked … “Oh, please, please! I don’t blame you for being angry with me, but, after all, it was such a shock, and Ben’s explanation sounded so logical.”

“That I’d done it as a publicity stunt?”

“Yes. And to drag me into it. He insisted that you were back of the leak to the newspapers. He warned me you’d string me along, but that you’d try to drag me into it so you could get the big news syndicates interested, focus a lot of publicity on yourself, and capitalize on it politically.”

“Yes,” he said bitingly, “you can see how much I’ve capitalized on it. Trying to play square with you is going to make me the laughingstock of the whole county.”

She nodded and said contritely, “I realized that when I heard about The Blade. I came here because I couldn’t go back on you. You’d been square and big and fine and genuine.”

“I presume,” he said, “Ben Trask sent you here and rehearsed you in what you were to say.”

“Ben Trask thinks I’m on an airplane headed for Mexico City to recuperate.”

“Trask was up here the day of the murder?” he asked.

She nodded.

“And the day before?”

Again she nodded.

“Do you suppose his interest in keeping things under cover is selfish?”

She shook her head.

“What’s your hold on George Cushing?” he asked.

She said simply, “He’s my father.”

Selby’s face showed his surprise. “Your what?” he asked.

“My father. He kicked me out to shift for myself when I was eleven. After I made fame and riches, he hunted me out.”

“And how about this preacher?” he asked.

She motioned him to a chair.

“I’m going to tell you the truth,” she I said. “I don’t care what happens. I don’t care what my father or Ben Trask think.”

“Go on,” he told her.

“No one knows very much about my past,” she said. “The fan magazines carry a synthetic story every once in a while about my having been raised in a convent, which is a lie. I was raised in the gutter.”

He stared at her in steady, watchful scrutiny.

“When I was seventeen,” she said, “I was sentenced to a reform school as an incorrigible. If I’d gone to the reform school, I’d have been incorrigible. But there was one man who had faith in me, one man who saw the reason for my waywardness.”

“You mean Larrabie?” Selby asked.

“Yes. He was a minister who was taking a great interest in human-welfare work. He interceded with the judge and managed to get me paroled for a year. He made me realize I should have some ambition, that I should try to do something for myself. At the time, I thought a lot of what he said was just the old hooey, but I was impressed enough by him and cared enough for him so I tried to make good. Four years later I was an extra in Hollywood. Those four years had been four years of fight. I’d never have stuck it out, if it hadn’t been for his letters; for his steady, persistent faith; for the genuine, wholehearted goodness of the man.”

“Go on,” he told her.

“You know what happened after that. I played extra parts for a year. Then I had a minor speaking part. A director thought I showed promise and saw that I had a lead in a picture.”

He nodded.

“Last week Larrabie telephoned me,” she said. “He said he had to see me right away, that he couldn’t come to Hollywood because of a matter which demanded his attention here. He told me he needed five thousand dollars — in fact, he told me that over the telephone.

“I went to the bank and drew out five thousand dollars in five one-thousand dollar bills. I came up here. He had a scenario he wanted to sell. It was entitled Lest Ye Be Judged. You know how hopeless it was. I explained to him that I didn’t have anything to do with the purchase of pictures. It was, of course, founded on my life story.”

“Then what?”

“Then he told me what he wanted with the five thousand dollars. A very close friend of his, a man by the name of Brower, was in a financial jam. Larrabie had promised to get him the money. He’d been working for months on that scenario. He thought it was a masterpiece. He felt that with me to give it a good word he could easily sell it for five thousand dollars. I told him to forget the scenario and gave him the five thousand dollars. I told him to consider it as a loan.”

“Did he tell you why he was registered here under the name of Brower?”

“He said he was working on some business deal and the man for whom he was working told him the thing must be kept undercover. He said he’d written the man from Riverbend, and the man had telephoned him; told him that it would be dangerous to come here and register under his right name; that the thing to do was to come here without anyone knowing he was here and register under a fictitious name.”

“Did he tell you any more about that?” Selby asked.

“He said the man asked him if he’d told anyone about having written. Larrabie said he hadn’t. Then the man said that was fine and to come here without letting a soul know — not even his wife. Poor Larrabie thought it would be less wicked to register under the name of someone else than it would to use a purely fictitious name. So he took Brower’s identity — borrowed his driving license and wallet. Brower was hiding. He’d cashed five thousand dollars in trust funds. He’d been robbed in Reno, then he’d gone on to Riverbend to ask Larrabie for help. Brower was waiting in Los Angeles to hear if Mr. Larrabie had sold the scenario for enough to make up the five thousand dollars.”

“Larrabie said he’d written a letter to the man he was to meet here?”

“Yes.”

“He didn’t tell you who the man was?”

“No.”

“Didn’t give you any idea?”

“No.”

“Look here,” Selby told her, “every time I’ve talked with you, you’ve purported to tell me the truth. Every time it’s turned out to be something less than or radically different from the truth.”

She nodded mutely.

“What assurance have I that you’re telling me the truth this time?”

She came toward him.

“Can’t you see?” she said. “Can’t you see why I’m doing this? It’s because you’ve been so splendid. So absolutely genuine. Because you’ve made me respect you. I’m doing this — for you.”

Selby stared at her thoughtfully.

“Will you stay here,” he asked, “until I tell you you can go?”

“Yes, I’ll do anything you say — anything!”

“Who knows you’re here?”

“No one.”

“Where’s Cushing?”

“I don’t know. He’s undercover. He’s afraid the whole thing is going to come out.”

“Why should he be so afraid?”

She faced his eyes unflinchingly and said, “If my real identity is ever known, my picture career would be ruined.”

“Was it that bad?” he asked.

She said, “It was plenty bad. Very few people would understand. Looking back on it, I can’t understand myself. Larrabie always claimed it was because I had too much natural energy to ever knuckle down to routine.”

“You staked Cushing to the money to buy this hotel?” Selby asked.

“Yes. And I keep this room. It’s mine. It’s never rented. I come and go as I want. I use it for a hide-out when I want to rest.”

“Did Larrabie know that — about your room here?”

“No. No one except my father and Ben Trask knew of this room.”

“Then why did Larrabie meet you here?”

“He talked with me over the telephone and said he was coming here on business. I told him I’d meet him here. He thought I was just coming up to see him.”

“And his business here didn’t have anything to do with you?”

“No.”

“Nor with your father?”

“No.”

“Did Larrabie know your father?”

“No. He’d never seen dad — except that he may have met him as the owner of the hotel.”

“But he must have known generally of your father?”

“Yes. He knew about dad years ago — things that weren’t very nice.”

“What’s been Cushing’s past?” Selby asked.

She shrugged her shoulders and said, “Pretty bad. I presume there was a lot to be said on his side, but it’s one of those things people wouldn’t understand. But, after all, he’s my father, and he’s going straight now. Can’t you see what a spot I was in? I had to lie, had to do everything I could to throw you off the track. And now I’m sorry. I tried my best to give you a hint about the real identity of the body when I said that he was a ‘Larry’ somebody from a town that had the name ‘River’ in it. I figured you’d look through the map, find out the number of California towns that had ‘River’ in their names, and telephone in to see if a pastor was missing.”

“Yes,” he said slowly, “I could have done that, probably would have, if I hadn’t had another clue develop.”

He started pacing the floor. She watched him with anxious eyes.

“You understand?” she asked.

“Yes.”

“I couldn’t have done any differently. You do see it from my standpoint, don’t you?”

“Yes, I see it from your standpoint.”

“‘But, you’re acting — so sort of — Tell me! This isn’t going to prevent us from being friends, is it? I admire and respect you. It’s meant a lot to me, just having met you. You’re sincere and genuine. There’s no pose about you, no false front. I don’t usually offer my friendship this way … I need friends like you. Do you understand? “

Selby stared steadily at her.

“Over there,” he said, waving his arm in the general direction of the courthouse, “there’s a girl waiting. She’s had faith in me and what I stand for. She’s staked her job on my ability to solve this mystery by four o’clock this afternoon, simply because she’s a wholehearted, loyal friend. She hasn’t any money, smart clothes, influential friends or fine houses.

“I don’t know whether I can tell you this so you’ll understand it, but I’ll try. If I give you my friendship, I’ll be running back and forth to Hollywood. I’ll gradually see the limitations of my friends here, limitations which aren’t deficiencies of character, but of environment. I’ll get so I unconsciously turn up my nose when I ride in rattling, dust-covered, cheap automobiles. I’ll adopt a patronizing attitude toward the things of this county and assume an urban sophistication.

“You asked me to understand why you lied to me. I do understand. From your viewpoint there was nothing else you could have done. Damn it, I can almost see your viewpoint clearly enough so it seems the logical thing for you to have done.

“To hell with it. Your life lies in the glitter and the glamour. Mine lies with the four-square friendships I’ve made in a community where everyone knows everyone else so intimately there’s no chance for a four-flusher to get by.”

He strode toward the door.

“Where are you going?” she asked, panic in her eyes.

“To solve that murder,” he said, “and to keep faith with a girl who would no more lie to me than she’d cut off her right hand.”

She stood staring at him, too proud to plead, too hurt to keep the tears from her eyes.

He stepped into the hallway, slowly closed the door behind him.

XIX

Selby pushed his way through the door of his private office to encounter the disapproving eyes of Sylvia Martin.

“Well?” she asked.

“She told me the truth, Sylvia,” he said, “the whole truth.”

“Again?” she inquired sarcastically.

He didn’t answer her directly, but said, “Sylvia, I want you to check my conclusions. I’m going to go over this thing with you step by step. First, I’m going to tell you what Shirley Arden told me. I’m going to ask you, of course, to regard it as a sacred confidence.”

He began at the beginning and told her everything the actress had told him. When he had finished she said slowly, “Then, if that story is true, Brower had no reason to murder Larrabie.”

Selby nodded.

“And Brower’s silence is because he’s trying to protect himself. If he ever admitted that he’d been robbed, lots of people would figure he’d simply squandered the money.”

Selby said, “Not only that, but Brower had assumed the responsibility of putting those funds into the form of cash. He was trying to outguess some claimant who didn’t have a leg to stand on, but who wanted to tie up the money, hoping he’d get some sort of a settlement. Brower would probably have killed himself rather than gone back and reported the loss of the money.

“The really significant thing about the whole business is that, despite the importance of getting that five thousand dollars, Larrabie wouldn’t leave Madison City. Now, then, Larrabie had written some man with whom he was to do business here. That man telephoned him, asked him particularly if anyone knew of the letter, and then asked Larrabie to come here and register under an assumed name, using the utmost secrecy.”

“Well?” she asked.

“The man who got the letter wasn’t the man to whom it was written,” Selby said.

“What are you talking about, Doug? You can’t know that.”

“So far,” he told her, “I am just indulging in theories. Now let’s start checking up on facts.”

She glanced at her wrist watch and said ironically, “Yes, my editor always likes facts. Particularly when the paper is going to accuse someone of murder.”

“The first thing to do,” Selby said, “is to study those photographs again.”

“Why?”

“To find out just when they were taken. Take a magnifying glass, Sylvia, and study every detail. See if you can find some time clue. While you’re doing that I’ll be doing some other stuff.”

He picked up the telephone and said, “Get me Sheriff Brandon.” A moment later he said, “Rex, I’ve got a lot of news and a lot of theory. The news isn’t worth a damn unless the theory checks with the facts, so I want to find out the facts.

“I’m going to give you the manufacturer’s number on that miniature camera. I want you to find out what dealer had such a camera in stock. Trace it through the wholesaler and retailer, get a description of the purchaser.”

He read off the numbers on the lens and body of the camera, and then said, “Just as soon as you get that information, let me know. But get it and get it at once, at all cost … And here’s something else Rex. Try to bring out any latent fingerprints on the space bar of that portable typewriter. Do it as soon as possible.”

“Okay,” the sheriff said.

Selby hung up the telephone and called the coroner.

“Harry,” he said, when he had the coroner on the line, “I want to know something about Larrabie’s suitcase.”

“All right, what about it?”

“You took it into your custody?”

“Yes.”

“Kept it in your office?”

“Yes, in the back room.”

“And Rogue, your police dog, was always on the premises?”

“Yes.”

“When was the dog poisoned?”

“Why, yesterday morning — you were there.”

“No, no; I mean when did you first find out he’d been poisoned?”

“It was sometime around twelve o’clock. I’d been out, and when I came back the dog seemed sick. He wagged his tail to show he was glad to see me, and then dropped down on the floor.”

“And where was the dog when you came back?”

“In my office; but there’s a narrow door leading to the backyard, so he could get out, if he’d wanted to.”

“But he was where he could guard the office?”

“Sure. No one could possibly have entered that office. Rogue would have torn them to pieces.”

“Thanks,” Selby said, “I just wanted to make certain. I think the poisoning of the dog is particularly important.”

“So do I,” Perkins said. “If I can find out who did it, you’ll have another homicide case on your hands.”

Selby hung up the telephone, to hear Sylvia exclaim eagerly, “Doug, these pictures were taken Wednesday noon.”

“How do you know?” he asked, his voice showing his excitement.

You can analyze the shadows, for the time of day. They show the picture was taken right around noon. Now the Rotary Club meets at the Madison Hotel every Wednesday. When it meets, there isn’t enough room for the members to park their cars on the main street and in the parking lot next to the hotel, so they spread down the side street and take every available parking space. At other times during the day it is very seldom the parking spaces on the side street are filled up.

“Now notice this picture. It shows the main street. Now here’s the next one; that’s looking down the side street. You see, there isn’t a single vacant parking space on the whole street. I’ll bet anything you want, these pictures were taken Wednesday noon, while the Club was having its meeting.”

Selby said slowly, “That’s darned good reasoning, Sylvia. I think I’ll have to put you on my staff.”

“You sure will,” she told him, “if we don’t have some facts for my city editor pretty quick. I can stall him just about so long, and then I’ll be finished. At that time I’ll be completely out of a job.”

“Well,” he told her, “you can’t get on up here, because I’ll be out of a job too.”

He picked up the camera, studied it carefully and put it back in its worn leather case.

“Why is the camera so important?” Sylvia asked. “And how could those pictures have been taken so long after Larabie’s death?”

“That,” he told her, “is the thing on which any real solution of this case must turn. It’s a fact which doesn’t coincide with any of the other facts, but really furnishes the key to the whole business, if it’s interpreted correctly.”

He picked up the telephone, called Doctor Perry, and when he had him on the phone, said, “Doctor, this is Doug Selby, the district attorney. For reasons which I won’t try to explain over the telephone, the poisoning of Perkins’ dog becomes a clue of greatest importance. How’s the dog coming along?”

“I’m going to pull him through,” Doctor Perry said. “I worked with him most of the night.”

“Can you tell me anything about the poison that was used?”

“I think,” Doctor Perry said, “that the poison was compounded by an expert. In other words, the man who did it was either a doctor or a chemist, a druggist or someone who knew a great deal about drugs, and probably something about animals.”

“I wonder if you can take time to run up to the office for a few minutes?” Selby asked. “I want to get some definite and detailed information. I’m expecting to bring this case to a head within the next couple of hours.”

“You mean you’re going to find out who put the poison there?”

“I think I’m going to go farther than that,” Selby told him, “and find out who murdered Larrabie. But keep that under your hat. I’m telling you because I want you to realize how important your cooperation may be.”

“I’m dropping everything and coming right up,” Perry promised.

“Thanks,” Selby told him.

He hung up the telephone, returned to a study of the strip of negatives; then he rang up the manager of the telephone company and said, “I’m particularly interested in tracing a call which was sent from Madison City sometime within the last week or ten days to William Larrabie at Riverbend, California. I wish you’d look back through your records and see what you can find out about that call, and let me know.”

Receiving a promise of assistance, Selby dropped the receiver back into place and then started pacing the floor, talking in the mechanical monotone of one who is thinking out loud. “A hotel,” he said, “is a peculiar place. It furnishes a temporary home for hundreds of people.

“Here in this hotel, on the night of the murder, we had a minister of the Gospel in one room, a young couple who saw fit to register under assumed names in an adjoining room. And, somewhere in the background, was another minister who was in a serious financial predicament. He had to have money and have it at once. It was an amount which was far beyond what he could hope to obtain by any legitimate means. And in that hotel we had a room kept by a prominent motion-picture actress. The hotel was operated by her father. No one knew of the relationship. No one knew of certain chapters in the life of this actress.”

“We happen to know these things about these few people. There were others about whom we don’t know, but who must have had their own family skeletons, their own fears and hopes. They were all sleeping under the one roof.”

“Brower wasn’t there,” she pointed out.

Selby smiled and said, “If you are going to be technical about it, there wasn’t any reason why Brower couldn’t have registered in the hotel in Los Angeles, left Los Angeles, gone to the Madison Hotel and taken a room under another name.”

Her face showed excitement. “Did he, Doug?” she said. “Did he? Oh, Doug, if we could only get something like that.”

He smiled and said, “Not yet, Sylvia, I’m simply mentioning possibilities.”

“But why point them out in just that way?”

“Because,” he said, “I want you to understand one fundamental thought, because it is of particular importance in the solution of this case.”

“What is it?” she asked. “I don’t see what you are getting at.”

“What I’m trying to establish is that people are, after all, very much alike. They have the same problems, the same complexities of life. Therefore, when we find what these problems and complexities are in the case of some of the people who were in the hotel, we shouldn’t make the mistake of considering that those problems must be interrelated merely because the people were temporarily thrown together in a physical environment.”

There was something ominous in her voice as she said, “Doug, are you starting out to prove that no matter what this actress did, she couldn’t have been … ”

Amorette Standish opened the door and said, “Doctor Perry’s here, all out of breath. Says he broke every speed record in town.”

“Show him in,” Selby said.

The door opened and Doctor Perry bustled into the room. He had quite evidently been hurrying, and was breathing through his mouth.

“Sit down there,” Selby told him, “and get your breath. I didn’t mean for you to run yourself to death getting here, and you’ll need some breath to answer questions … By the way, Amorette, I want to give you some instructions. And, Sylvia, you can help me, if you’ll step this way for a moment. You’ll pardon us for a minute, Doctor?”

“I’ll say!” Doctor Perry panted. “I could use a breathing spell very nicely.”

Selby stepped into the outer room, drew Amorette and Sylvia close to him.

“Now, listen,” he said; “a call may come in about that camera. I’m anxious to find out … ”

“Yes,” Amorette interrupted, “Sheriff Brandon telephoned. He said not to disturb you, but to tell you he’d talked with Mrs. Larrabie. She told him the minister got the camera through a retailer who sent to a dealer in Sacramento for it. The sheriff has a call in for the retailer in Riverbend. And he’s already talked with the wholesaler in Sacramento. They’re looking for the number and are going to call back. The sheriff said both calls would come to this office.”

“All right,” Selby said. “If the call comes in while I’m talking with Doctor Perry and you get the numbers, just come to the door and beckon to me. And, Sylvia, I think you’d better be where you can listen in on that telephone call, and be absolutely certain that the numbers are correct.”

“But, when you already have the camera,” Sylvia said, “why be so worried about the numbers?” …

Selby stepped back into the private office, closed the door and said, “Doctor, you know something of the facts about Larrabie’s death.”

“I’ve read the papers. What about it?”

“It’s my theory,” Selby said, “that the man who arranged things so Larrabie took that dose of poison was a man who must have known something of medicine, and who must not only have access to morphia but knew how to put it in a five-grain tablet.”

Doctor Perry nodded.

“Now, then, you say that the one who poisoned this dog showed a considerable knowledge of medicine. I want to know just what you mean by that?”

“I mean,” Doctor Perry said, “that as nearly as I can find out, the poisoned meat contained not one active ingredient, but two. Moreover, the poisoning had been very skillfully compounded and had been placed in food combinations which would be particularly attractive to a dog.”

“Now in order to plant that poison on the inside of the room, the poisoner must have had access to that room. Isn’t that right?”

Doctor Perry’s forehead twisted into a perplexed frown. “Why, of course,” he said, “that goes without saying.”

“Therefore the dog wouldn’t have been poisoned merely so the poisoner could have had a few minutes in that room.”

“Why?” Doctor Perry asked.

“Because he already must have had access to the room when he planted the poison.”

“That’s right … But wait a minute. How could he have planted the poison with the dog there?”

Selby said, “That’s exactly the point. You see, Doctor, we have more definite clues to work on when it comes to trapping the poisoner of the dog than we do in trapping the murderer of William Larrabie. Therefore, I want to be reasonably certain that one and the same man was guilty of both the dog poisoning and the murder. Then I want to concentrate on getting that dog poisoner.”

“I see what you’re getting at,” Doctor Perry said slowly, “and I think I can assure you, Mr. Selby, both the dog poisoning and Larrabie’s death had this much in common — they were the work of some man who knew something of drugs, who had an opportunity to compound a five-grain tablet containing a lethal dose of morphia, or who had access to such a tablet. Also, the man knew something about dogs.”

Selby stared steadily at Doctor Perry. “Is there,” he asked, “any chance that Harry Perkins might have poisoned his own dog?”

Doctor Perry’s face showed startled surprise. Then he said swiftly, “Why, Mr. Perkins was all worked up about it. He was going to kill the man who did it.”

“Nevertheless,” Selby said, “he might have poisoned the dog and then rushed him to you in order to counteract the effects of the poison.”

“But why would he have done that?”

“Because he would want to make it look like an outside job. Mind you, Doctor, I’m not accusing Perkins; I’m simply asking you a question.”

Doctor Perry said, “You mean that unless the dog had been absent from the premises — which he wasn’t — the person who dropped that poison inside of the room must have been someone the dog knew. A stranger might have tossed it over the fence, but a stranger couldn’t have planted it in that room.”

“That,” Selby told him, “is right. Now then, Perkins, I believe, is a registered pharmacist.”

“I believe he is, yes.”

“Isn’t it rather unusual that Perkins would have detected the symptoms of poisoning and brought the dog to you as soon as he did?”

“Well,” Doctor Perry said slowly, “it depends, of course; some people know their dogs so well they can tell the minute anything goes wrong. Still … ” He let his voice trail away into thoughtful silence.

At that moment Amorette Standish knocked on the door, opened it and beckoned to Selby.

“Excuse me for a moment,” Selby said. “Although, on second thought, Doctor, I guess that’s everything I wanted to get from you. I’d like very much to have you make some investigation along the theory I’ve outlined and see if you can find out anything.”

Doctor Perry clamped on his hat, strode purposefully toward the door.

“You can count on me,” he said, “and also on my absolute discretion. I’ll be at the coroner’s for a few minutes, if you want to reach me. I have some questions to ask him.”

“Thanks, Doctor,” Selby said.

When Doctor Perry had left the office, the district attorney turned to Amorette Standish. “We’ve got the numbers,” she said in a low voice.

The door of the other office opened as Sylvia Martin came from the extension line. She nodded and said, “I have them here. The sale was made to Mr. Larrabie shortly before Christmas of last year.”

“Well, let’s check the numbers,” Selby said.

He led the way to the private office, took the camera from the case, read out the numbers. Both girls nodded their heads. “That’s right,” they said.

At that moment the door of the outer office opened and Sheriff Brandon entered the room.

“Find any fingerprints on the space bar of the typewriter?” Selby asked.

“Yes, there are a couple of good ones we can use.”

“Were they those of the dead man?”

“No.”

“By the way,” Selby said, “what number did I give you on that camera?”

The sheriff pulled a notebook from his pocket, read forth a string of figures.

Sylvia Martin exclaimed, “Why, those aren’t the figures that we have, and … Why, they aren’t the figures that are on the camera!”

Doug Selby grinned. “Rex,” he said, “while I’m outlining a damn good story to Sylvia, would you mind sprinting down the courthouse steps? You’ll find Doctor Perry just getting into his automobile. Arrest him for the murder of William Larrabie.”

XX

Sylvia Martin stared at Selby with wide-open eyes. “You aren’t bluffing, Doug?”

“No,” he told her.

“Then give it to me,” she said, looking at her wrist watch, “and hit the high spots. I’ve got to get this story licked into shape. Give me the barest outline.”

“Let’s go back to what we know,” he told her. “We know that Larrabie had business here. It was business other than raising the five thousand dollars.”

“How do we know that?”

“Because he didn’t leave here after he got the five thousand dollars.”

“I see.”

“We know that he wrote someone here in Madison City, that this someone telephoned him and made arrangements for him to come to Madison City with the utmost secrecy. That was the person with whom Larrabie was doing business, and it’s reasonable to suppose that business was connected in some way with the Perry Estate, because Larrabie’s briefcase contained documents relating to two independent pieces of business: the Perry Estate and the scenario.

“Remember, I warned you that all people had problems; that we mustn’t make the mistake of feeling that all of these problems must be related merely because the people happened to be under the same hotel roof. As a matter of fact, the five thousand dollars, Brower’s troubles over losing the money, and Shirley Arden’s relationship with Larrabie, all were entirely independent of the business which actually brought Larrabie here.”

“Getting the five thousand was important, but there was something else which was unfinished and which had to do with someone here in Madison City.

“Now the man to whom Larrabie wrote his letter and with whom he had his business must have been someone Larrabie was aiding. He’d hardly have followed instructions from someone hostile to him.”

“Go on,” she said.

“There is a remarkable coincidence which has escaped everyone’s attention,” he said, “and probably furnishes the key to the entire situation, and that is that the initials of both claimants to the money in the Perry Estate are the same. Therefore, if Larrabie had written a letter addressed simply to ‘H.F. Perry’ at Madison City, that letter might have been delivered either to Herbert F. Perry or to Dr. H. Franklin Perry. And if the letter contained evidence relating to the marriage of the two decedents, and had fallen into the possession of Doctor Perry, naturally Doctor Perry would have realized his only hope to beat Herbert Perry’s claim was to suppress this evidence. Now in the newspaper clippings in Larrabie’s briefcase, the claimant to the estate was described simply as ‘H.F. Perry.’