5 Times That Disease Unexpectedly Changed American History

Very few people foresaw the full impact of COVID-19 in America. And with the president’s recent announcement that he himself has been infected, there is much uncertainty about the repercussions his illness will have on his party, the government, the stock market, and the electorate.

But this is the nature of infectious diseases: the full impact of their arrival, departure, and consequences are rarely foreseen.

This has been seen repeatedly throughout history. During the Civil War, for example, America expected there’d be casualties from soldiers dying in the field of combat. What they didn’t expect was that most would die far from the fighting, as soldiers crowded in camps spread cholera, smallpox, and other infectious disease. More than half of the war dead were victims of disease.

Here are five times major illnesses had unexpected outcomes.

Malaria Fueled the American Slave Trade

Among the earliest European settlers to America were planters who arrived in South Carolina to grow rice. They soon discovered the marshy lowlands where they planted were infested malaria-bearing Anopheles mosquitoes. The disease, which reproduces in red blood cells, proved fatal for white workers in the fields, and planters had trouble maintaining their crops. But they discovered that recently enslaved Africans had a degree of immunity to malaria because of the genetic condition sickle-cell anemia. Rice became a successful crop, followed by cotton, both tended by slaves.

Planters didn’t know what gave the enslaved Africans their ability to endure malaria. They assumed it was because they were genetically hardier. This was far from true; half of all Black children born into American slavery died before reaching the age of five.

Disease Was a Sign of American Success

At the time of the Revolution, Americans enjoyed far better health than their contemporaries in Europe. The average height — a good indication of the state of health — was 68.1 inches, just one inch lower than the average height today (the average European measured 65.76 inches). Roughly 60 percent of children raised in the country survived to age 60. (page 123, “Deadly Truth”)

According to The Deadly Truth: A History of Disease in America by Gerald N. Grob, almost all Americans of the early 1800s resided in the country, leading exceptionally healthy lives. They lived far apart, with little exposure to strangers bearing illnesses; they had healthy diets and a clean environment.

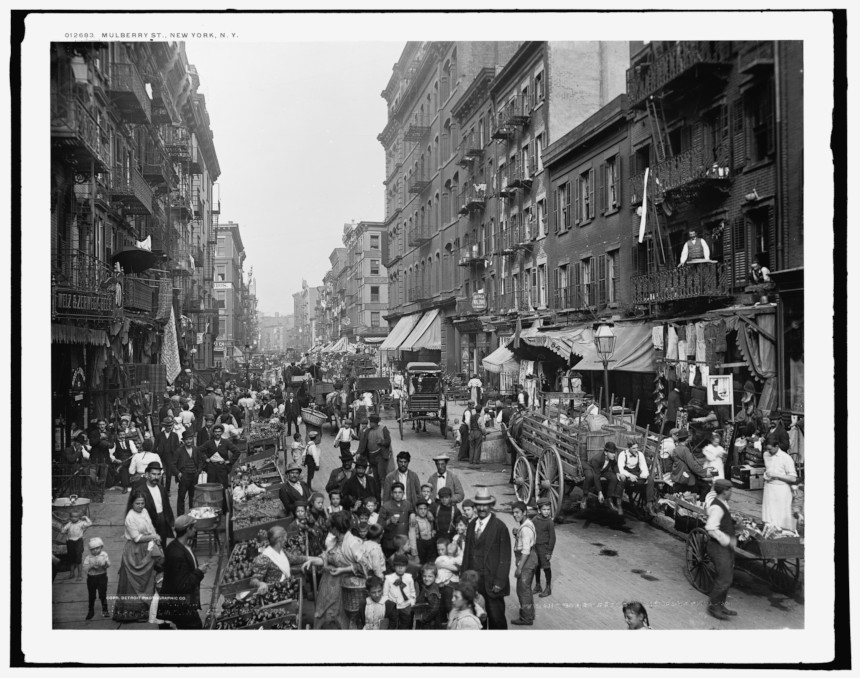

But the population began shifting toward the cities, according to Grob. Between 1800 and 1850, for instance, the population of Philadelphia increased 500 percent, consisting mostly of Americans leaving the country for the city. They were attracted by the commercial possibilities and the opportunity to enrich themselves beyond anything they could realize on a farm.

They came despite the already high risk of contracting a fatal disease in the city. Between 1721 and 1792, Boston was hit by seven epidemics. An outbreak of yellow fever in 1793 killed 1 in 10 Philadelphians.

Urban crowding made disease transmission easier. Water supplies became contaminated. Immigrants, sailors, and visitors brought fresh injections of diseases. Cholera and yellow fever spread rapidly, and cities didn’t have the resources to care for the sick. In big cities like New York and Boston, only 16 percent of children reached their 60th birthday. By 1830, the average male height in America had fallen to under 67 inches.

A Mysterious Illness in Midwestern Livestock Began Emptying Towns

In the 1800s, settlers in the Ohio River Valley noticed livestock sometimes developed a trembling in their legs that soon led to collapse and death. Shortly afterward, their owners showed the same signs, as well as abdominal pains and vomiting. Farmers called it “milk sickness” and believed it was caused by an infectious agent.

The disease proved highly fatal in pioneer settlements, sometimes claiming up to half the residents. Areas of Kentucky and Illinois were especially hard hit. One of its victims was Abraham Lincoln’s mother.

The disease abated as the land became settled and animals began grazing in pasture land instead of the wilderness. It wasn’t until 1923 that Dr. Anna Pierce Hobbs Bixby learned from a Shawnee woman the cause of the sickness. Sheep and cattle were eating snake root, a member of the daisy family, which contains tremetol, a poison so strong it can kill animals and lethally poison its meat and milk. But in the days before it was discovered, the flow of settlers stayed away from areas where milk sickness was reported.

Another Disease Brought Prosperity to Colorado

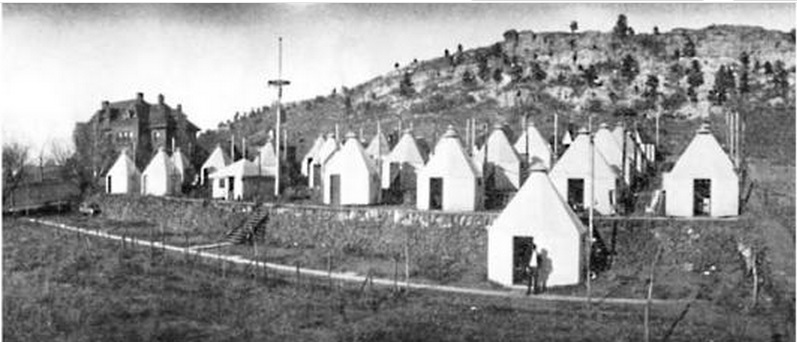

America’s number-one killer in the 1800s was tuberculosis. Doctors didn’t understand its cause or course, but it seemed to be connected with damp, polluted air. So doctors advised TB patients to move to higher altitudes, where the air was dry and conditions sunny. The recommendation was partly useful. The decreased oxygen levels at high altitudes slowed the growth of the mycobacterium-causing organism. And the sunlight and fresh air was always good for patients.

There were plenty of high altitudes and sunny weather in Colorado. Prior to the 1860s, it had been just another empty stretch of the western wilderness, sparsely peopled by miners and prospectors. But soon a growing number of sanitariums opened in Denver, Boulder, and Colorado Springs, and began to fill with tubercular patients. In time, they made up a third of the state’s population.

Cities grew up around the sanitariums, which attracted caregivers, support staff, and visitors to the patients. And TB patients often helped the town develop, bequeathing money to build streets and schools. In Denver alone, the population rose from 4,700 in 1870 to 106,000 in 1890.

Cleaning Up the Cities had Unintended and Fatal Consequences

Americans were shocked when a polio epidemic struck New England in 1916. For years, the incidence of the viral infections had declined almost to insignificance. Now, suddenly, 9,000 people had contracted the virus and 2,400 died — a fatality rate of 27 percent. The reason for the resurgence was completely unexpected.

Polio is caused by one of four viral strains. In the days before the Salk vaccine, most cases of polio ran their course in a day or two without serious complications. Only one case in 100 produced clinical symptoms, and even fewer caused paralysis. Most people experienced it as a low fever, headache, sore throat, and discomfort. But if the virus attacked the spine or the muscles controlling breathing, the consequences were quick and often fatal.

Up to the 1900s, most children in cities lived in crowded conditions and had been exposed to one of the strains at an early age. Or they gained immunity from maternal antibodies passed on to them as infants. Either way, most children growing up the congested cities were immune.

But as housing became less crowded and cleaner, there were fewer opportunities for exposure. A generation matured with little or no exposure and immunity. Polio swept through these communities quickly, striking down defenseless Americans. Franklin D. Roosevelt is a good illustration. He had grown up in wealth and comfort, and so had no immunity when the virus hit him in 1921 at the age of 39.

Featured image: Ward K, Armory Square Hospital, Washington, D.C., 1864 (Library of Congress)

World Alzheimer’s Month: The Mind of the Matter

Every September, Alzheimer’s Disease International mounts the World Alzheimer’s Month campaign. For the last eight years, the group has aimed to generate awareness surrounding dementia while dispelling misconceptions and misinformation. The official World Alzheimer’s Day comes later in the month, on September 21. ADI serves as the connection tissue for more than 100 other organizations across the world while teaming with corporate partners and consulting with WHO, the World Health Organization. In the spirit of the month, here are five things from ADI that you and your loved ones need to remember.

1. Dementia Isn’t Just One Thing

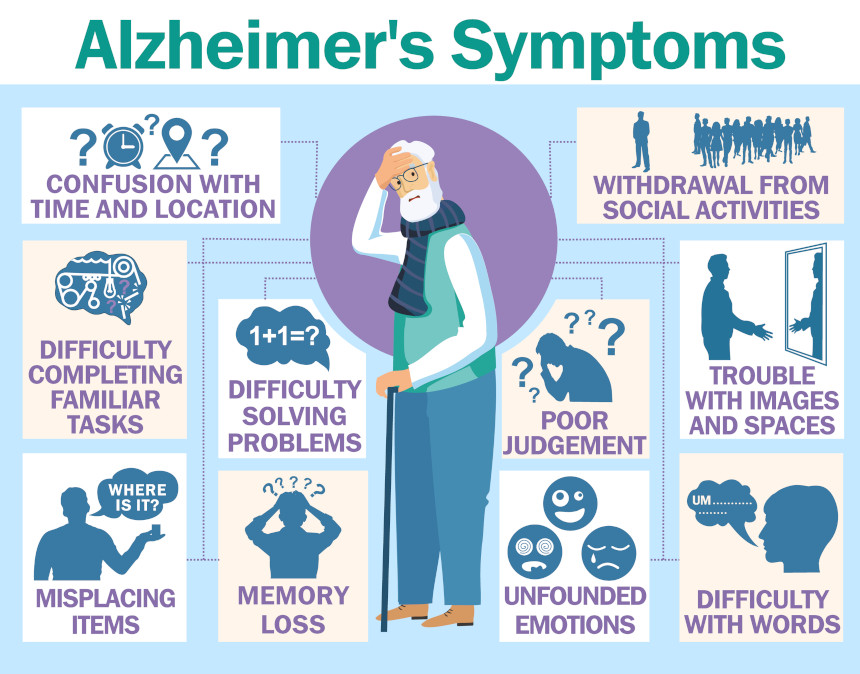

Medical professionals identify more than 100 specific kinds of dementia. While Alzheimer’s is associated with up to 60 percent of all cases, other frequently noted types include dementia with Lewy bodies, fronto-temporal dementia, and vascular dementia. Generally, various kinds of dementia have some symptoms in common. The most well-known is memory loss. Some patients struggle with routine conversational comprehension, or with finding the word that they wanted to use while speaking. A person may also have issues with conducting a familiar task, like forgetting how to operate a frequently used device. Also, people coping with dementia may experience changes in their overall mood or personality.

2. It’s a Worldwide Problem

According to ADI, around 50 million people are dealing with dementia around the globe right now. A new case appears every three seconds. Also, dementia is not just limited to the elderly. Symptomatic persons under the age of 65 are categorized as young or early onset dementia. As a personal aside, my mother-in-law was diagnosed with early onset at the age of 55.

3. It’s Not Necessarily Hereditary

A common fear among the children of Alzheimer’s patients is the notion of the disease being hereditary. It can run in families, but the occurrences are rare. When these instances do happen, it’s typically tied to an inherited genetic mutation that tends to be associated with early onset cases. When that mutation is present, the possibility of siblings or offspring developing the disease is actually one in two. In families where the Alzheimer’s is present later in life (over 65), close relatives still have a chance to develop dementia that’s three times greater than someone without the disease present in their family.

4. There’s No Cure … For Now

While a variety of drugs, treatments, and therapies are used to counteract the effects of dementia, there is presently no overall cure. Progression can be slowed up to 18 months with the right treatment, while medications exist that treat specific symptoms. Caregivers, both familial and professional, became a major component of support as the dementia progresses. The Alzheimer’s Association lists a number of treatment options that cover sleep disruption, behavior, and memory loss, but there is no cure as such at the moment. In an article from last year, The Mayo Clinic detailed some of the new therapies and approaches that are being explored by researchers, including studies of how vascular issues can be associated with dementia and the development of medication to fight the plaques that hamper brain function.

5. How You Live Now Helps You Later

There’s no silver bullet that prevents anyone from developing Alzheimer’s. However, there are baseline recommendations that anyone can follow that can help stave off the development of dementia. Research has shown that general fitness helps, which starts with healthy eating. Studies have shown that physical activity is a benefit; even if you don’t work out regularly, going for walks and spending time in active situations improves your health measurably over spending every day in sedentary way. Mental activity is important; reading regularly is a huge benefit, as is engaging in mentally stimulating activities like doing puzzles (of both the boxed and book-based variety), writing, or playing games of the kind found at sites like Lumosity. Regular social interaction, even if done via phone, Zoom, etc. is also shown to have positive results in terms of brain activity.

Featured image: awsome design studio / Shutterstock

Your Weekly Checkup: The Unnerving Resurgence of a Polio-like Illness

“Your Weekly Checkup” is our online column by Dr. Douglas Zipes, an internationally acclaimed cardiologist, professor, author, inventor, and authority on pacing and electrophysiology. Dr. Zipes is also a contributor to The Saturday Evening Post print magazine. Subscribe to receive thoughtful articles, new fiction, health and wellness advice, and gems from our archive.

Order Dr. Zipes’ new book, Damn the Naysayers: A Doctor’s Memoir.

Acute flaccid myelitis (AFM) is causing a big stir in the U.S. because it causes acute paralysis in children similar to polio. Here’s what we know and don’t know about this frightening disease.

According to the Centers for Disease Control, AFM is a paralytic syndrome that impacts the nervous system, mainly the spinal cord. The affected individuals, most often children, can present with polio-like symptoms, including weakness and pain in the arms and legs, difficulty moving the eyes, drooping eyelids or facial droop and weakness. Slurred speech and problems with swallowing or breathing can also occur.

The onset can be particularly frightening for parents, who should seek medical care right away if their child develops sudden weakness or loss of muscle tone in the arms or legs. While AFM is scary, it should be emphasized that it is a rare disorder, affecting one child in a million annually.

AFM can be difficult to diagnose because it shares many of the same symptoms as other neurologic diseases, like transverse myelitis and Guillain-Barré syndrome.

Symptoms have been most similar to complications of infection with certain viruses, including poliovirus, non-polio enteroviruses, adenoviruses, and West Nile virus. It is not polio, since all of the AFM cases have tested negative for poliovirus. The cause of AFM remains unknown, and no virus or bacteria has been consistently identified. Some information suggests an association between enterovirus D68 and acute flaccid myelitis.

While AFM is very rare, those affected may require extensive physical therapy. The long-term effects are variable. Some patients diagnosed with AFM recover quickly, while others need ongoing care. Some children paralyzed by AFM have eventually regained their ability to walk over time.

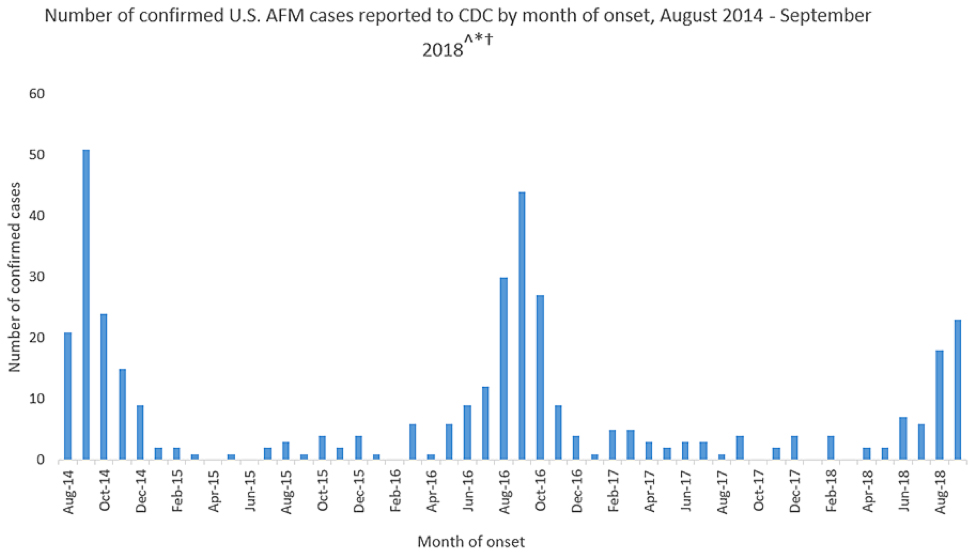

Strangely, incidents of the disease appear to spike in the fall of even-numbered years, such as 2014, 2016, and 2018, the reasons for which are not fully understood. From 2014 through September 2018, the CDC has received information on a total of 386 confirmed cases of AFM across the U.S. So far in 2018, there are 62 confirmed cases of AFM, occurring in 22 states.

While the cause of most of the AFM cases is unknown, one should practice disease prevention steps, such as staying up-to-date on vaccines, washing hands and maintaining cleanliness, and protecting oneself from mosquito bites that can carry West Nile virus and other vector-borne diseases.

No specific treatment exists at present for AFM, but if AFM is suspected, one should contact a physician promptly. AFM is diagnosed by examining a patient’s nervous system, combined with magnetic resonance imaging to investigate a patient’s brain and spinal cord, lab tests on the cerebrospinal fluid around the brain and spinal cord, and nerve conduction studies (impulses sent along a nerve fiber). It is important that the tests are done as soon as possible after the patient develops symptoms. Physical or occupational therapy to help with arm or leg weakness caused by AFM may be useful.

A final note: prevention is the byword in health care. As an adult, be sure you’re vaccinated against diseases that can be prevented such as flu, pneumococcus, and shingles. Be sure your children are vaccinated against a host of diseases.

I read recently about parents holding chickenpox parties, so their children could catch the disease from infected friends. This is wrong. The actual disease can cause high fever, itchy, watery blisters, headache, and in severe cases, dizziness, disorientation, rapid heartbeat, shortness of breath, tremors, loss of muscle coordination, worsening cough, vomiting, or stiff neck.

The best choice is prevention. The vaccine confers immunity without those terrible signs and symptoms.