The Young and the Selfless

At a bustling primary care clinic in rural Guatemala, Gautam Desai speaks with a mother and her daughters. The girls, ages 2 and 4, are two of nearly 300 patients that Desai and his volunteer team will examine in an auditorium turned makeshift medical center in the mountain town of San Juan Alotenango. Desai’s team includes 11 doctors and 39 med students from Kansas City University, where he’s a physician and family medicine professor, and the room in the town’s municipal building buzzes with a noisy collision of conversations, crying babies, and rambunctious kids.

Desai speaks calmly above the clatter. His two young patients have colds, so he prescribes nasal spray, vitamins, and Tylenol. Such common remedies may seem unremarkable, but for many rural residents in developing countries like Guatemala, Tylenol is a big deal. Nasal spray is a big deal. Anything you might buy at your local drug store is a big deal, from sunscreen to reading glasses. In fact, the team hands out around 100 pairs of reading glasses a day during this two-week annual trip, and it can be a life-changing moment, particularly for tradespeople such as weavers who hand-sew huipils, the colorful, patterned garments worn by many Guatemalan women.

“If they can’t see, they can’t work,” Desai says.

Desai has made these simple yet significant gestures to patients in multiple countries. Over the past 20 years, his teams have treated roughly 40,000 people, not just in Guatemala, but through twice-a-year clinics in Kenya and a once-a-year clinic in the Dominican Republic. Here in Guatemala, his American students and professionals see up to 400 patients a day with conditions ranging from arthritis to rashes.

“I think working abroad re-centers us on why we’re passionate about medicine.” –fourth-year med student Yana Klein

Despite his compassion and his passion for healing the sick, the modest, mellow Desai, who looks like David Duchovny in scrubs, initially resisted a career in medicine. He had seen the long hours worked by his father, aunt, and multiple family members, all of whom were physicians.

“My dad would never take a vacation,” says Desai, who was born in India but moved to Michigan with his family at age 5. “We’d have to force him to come to graduations and stuff like that.” Determined to enjoy life, Desai traded his pre-med studies at Boston University for a degree in psychology. He was contemplating a career in real estate when his brother, also a physician, encouraged him to consider osteopathic medicine. Desai was intrigued by this more holistic approach to healthcare that focuses not simply on treating symptoms but understanding how patients’ lifestyles and environment affect wellness.

“I liked the idea of doing more than just giving people a prescription,” says Desai, who is director of the honors track in global medicine at KCU. “I liked the idea of educating patients. I liked the idea of giving patients skills to help themselves and examining everything else in their lives — not just seeing that the patient has headaches, but maybe they get headaches because they’re depressed or because they don’t like their work situation or their home situation.”

After earning his medical degree from Michigan State, he joined KCU in 2000. When a dean learned that he spoke Spanish, he was invited on a KCU trip to Guatemala. Soon he was leading the trips, which are supported by DOCARE International, a nonprofit focused on healthcare in under-resourced communities. For a man who was once worried about working too many hours, leading trips in three countries — while also seeing patients and supervising residents at KCU’s Family Medicine Residency Program — is a heavy load.

“He’s working on these trips year-round,” says volunteer Sarah King, a med student who graduated in May 2020. “There’s so much organization that goes into it. But he does a good job delegating to students to get us involved. He has fostered community and camaraderie.”

Students work hard. Each morning, they lug supplies from their hotel in the Spanish colonial city of Antigua and load large cases onto buses for a roughly three-hour round-trip drive. The clinics are held in a different town each day. Students talk to patients, obtain their history, and conduct a physical exam. A physician or physician’s assistant then meets the patient and reviews the findings. Together, they develop a treatment plan.

The students are well supervised — “We’re not like, ‘Hey, go take that appendix out,’” Desai jokes — and they obtain invaluable hands-on experience in unique circumstances. One student talked excitedly on the bus ride back to Antigua about using a portable ultrasound to examine a large ovarian mass. Students also improve their Spanish and help people who often have never seen a doctor. Those opportunities are a big reason why med students attend KCU, Desai notes. Working abroad will not only make them better doctors, many students say, but it has encouraged them to work in underserved communities at home.

“I think working abroad re-centers us on why we’re passionate about medicine, and with the lack of resources here, it makes us use our brains in a different way,” says Yana Klein, a fourth-year medical student and one of the trip’s student leaders.

Another benefit: Students are exposed to a level of poverty unlike anything they’ve seen in the U.S. The encounters make them more empathetic. Klein mentions her interaction with a 96-year-old widow who arrived at a clinic with age-related ailments. “I offered a little bit of help with her pain,” says Klein, but just as important to the patient was the human contact. “We talked about her anxiety and sadness. It didn’t seem like much, but she started crying because she was so grateful. Just giving someone a little bit of time and kindness can go a long way.”

That emphasis on empathy, Desai believes, will remain with students as they pursue their medical careers. And he has experienced locals’ gratitude as well. For each of his annual visits to Guatemala, Desai spends about $30 for 30 baby chicks, paid for by KCU staff who contribute to his “chicken fund.” The volunteer team provides two chicks to various local patients who farm or know how to raise them. The chicks will grow to be egg-laying chickens, providing families with eggs, which provide both a nutritional boost and a reduction in food costs (some families also sell the eggs).

“God sends the American doctors here,” one 70-year-old patient says through a translator after receiving two chicks.

Desai’s natural humility makes him cautious about basking in the adulation of patients, but still, it feels good to be appreciated. “Sometimes we go back to a village and someone recognizes us and says, ‘Hey, I’m following your advice,’” he says. “Those moments make me happy.”

Ken Budd is the author of The Voluntourist and the host of 650,000 Hours, an upcoming web series on travel and real-life American heroes.

This article is featured in the September/October 2020 issue of The Saturday Evening Post. Subscribe to the magazine for more art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

Featured image: Training station: Dr. Desai and a med student treat a young patient in Kenya. “I liked the idea of giving patients skills to help themselves,” he says. (Courtesy Gautam Desai)

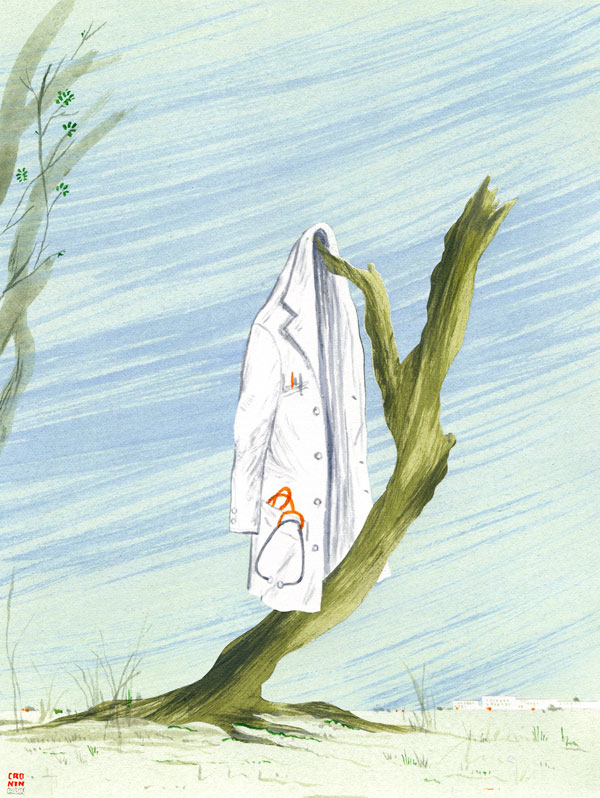

Cartoons: Doctor, Doctor

Want even more laughs? Subscribe to the magazine for cartoons, art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

Evan D. Diamond

August 7, 1954

Chon Day

September 16, 1950

Al Johns

September 16, 1950

Rodriguez

October 11, 1952

Wesley Thompson

October 11, 1952

Al Johns

October 20, 1951

Don Tobin

October 25, 1952

Walt Wetterberg

November 17, 1951

Bill Mittlebeeler

December 5, 1953

Goldstein

March 7, 1953

Want even more laughs? Subscribe to the magazine for cartoons, art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

Cartoons: The Doctor Is In

Want even more laughs? Subscribe to the magazine for cartoons, art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

Bill Harrison

December 1, 1951

Bernhardt

November 3, 1951

George Smith

September 15, 1951

Galagher

September 8, 1951

Al Johns

July 4, 1959

Bill K

January 5, 1952

Vick Ericson

December 29, 1951

All cartoons: SEPS.

How Doctors Die

Years ago, Charlie, a highly respected orthopedist and a mentor of mine, found a lump in his stomach. He had a surgeon explore the area, and the diagnosis was pancreatic cancer. This surgeon was one of the best in the country. He had even invented a new procedure for this exact cancer that could triple a patient’s five-year-survival odds—from 5 percent to 15 percent—albeit with a poor quality of life. Charlie was uninterested. He went home the next day, closed his practice, and never set foot in a hospital again. He focused on spending time with family and feeling as good as possible. Several months later, he died at home. He got no chemotherapy, radiation, or surgical treatment. Medicare didn’t spend much on him.

It’s not a frequent topic of discussion, but doctors die, too. And they don’t die like the rest of us. What’s unusual about them is not how much treatment they get compared to most Americans, but how little. For all the time they spend fending off the deaths of others, they tend to be fairly serene when faced with death themselves. They know exactly what is going to happen, they know the choices, and they generally have access to any sort of medical care they could want. But they go gently.

Of course, doctors don’t want to die; they want to live. But they know enough about modern medicine to know its limits. And they know enough about death to know what all people fear most: dying in pain and dying alone. They’ve talked about this with their families. They want to be sure, when the time comes, that no heroic measures will happen—that they will never experience, during their last moments on earth, someone breaking their ribs in an attempt to resuscitate them with CPR (that’s what happens if CPR is done right).

Almost all medical professionals have seen too much of what we call “futile care” being performed on people. That’s when doctors bring the cutting edge of technology to bear on a grievously ill person near the end of life. The patient will get cut open, perforated with tubes, hooked up to machines, and assaulted with drugs. All of this occurs in the Intensive Care Unit at a cost of tens of thousands of dollars a day. What it buys is misery we would not inflict on a terrorist. I cannot count the number of times fellow physicians have told me, in words that vary only slightly, “Promise me if you find me like this that you’ll kill me.” They mean it. Some medical personnel wear medallions stamped “NO CODE” to tell physicians not to perform CPR on them. I have even seen it as a tattoo.

To administer medical care that makes people suffer is anguishing. Physicians are trained to gather information without revealing any of their own feelings, but in private, among fellow doctors, they’ll vent. “How can anyone do that to their family members?” they’ll ask. I suspect it’s one reason physicians have higher rates of alcohol abuse and depression than professionals in most other fields. I know it’s one reason I stopped participating in hospital care for the last 10 years of my practice.

How has it come to this—that doctors administer so much care that they wouldn’t want for themselves? The simple, or not-so-simple, answer is this: patients, doctors, and the system.

To see how patients play a role, imagine a scenario in which someone has lost consciousness and been admitted to an emergency room. As is so often the case, no one has made a plan for this situation, and shocked and scared family members find themselves caught up in a maze of choices. They’re overwhelmed. When doctors ask if they want “everything” done, they answer yes. Then the nightmare begins. Sometimes, a family really means “do everything,” but often they just mean “do everything that’s reasonable.” The problem is that they may not know what’s reasonable, nor, in their confusion and sorrow, will they ask about it or hear what a physician may be telling them. For their part, doctors told to do “everything” will do it, whether it is reasonable or not.

The above scenario is a common one. Feeding into the problem are unrealistic expectations of what doctors can accomplish. Many people think of CPR as a reliable lifesaver when, in fact, the results are usually poor. I’ve had hundreds of people brought to me in the emergency room after getting CPR. Exactly one, a healthy man who’d had no heart troubles (for those who want specifics, he had a “tension pneumothorax”), walked out of the hospital. If a patient suffers from severe illness, old age, or a terminal disease, the odds of a good outcome from CPR are infinitesimal, while the odds of suffering are overwhelming. Poor knowledge and misguided expectations lead to a lot of bad decisions.

But of course it’s not just patients making these things happen. Doctors play an enabling role, too. The trouble is that even doctors who hate to administer futile care must find a way to address the wishes of patients and families. Imagine, once again, the emergency room with those grieving, possibly hysterical, family members. They do not know the doctor. Establishing trust and confidence under such circumstances is a very delicate thing. People are prepared to think the doctor is acting out of base motives, trying to save time, or money, or effort, especially if the doctor is advising against further treatment.

Some doctors are stronger communicators than others, and some doctors are more adamant, but the pressures they all face are similar. When I faced circumstances involving end-of-life choices, I adopted the approach of laying out only the options that I thought were reasonable (as I would in any situation) as early in the process as possible. When patients or families brought up unreasonable choices, I would discuss the issue in layman’s terms that portrayed the downsides clearly. If patients or families still insisted on treatments I considered pointless or harmful, I would offer to transfer their care to another doctor or hospital.