5 Times That Disease Unexpectedly Changed American History

Very few people foresaw the full impact of COVID-19 in America. And with the president’s recent announcement that he himself has been infected, there is much uncertainty about the repercussions his illness will have on his party, the government, the stock market, and the electorate.

But this is the nature of infectious diseases: the full impact of their arrival, departure, and consequences are rarely foreseen.

This has been seen repeatedly throughout history. During the Civil War, for example, America expected there’d be casualties from soldiers dying in the field of combat. What they didn’t expect was that most would die far from the fighting, as soldiers crowded in camps spread cholera, smallpox, and other infectious disease. More than half of the war dead were victims of disease.

Here are five times major illnesses had unexpected outcomes.

Malaria Fueled the American Slave Trade

Among the earliest European settlers to America were planters who arrived in South Carolina to grow rice. They soon discovered the marshy lowlands where they planted were infested malaria-bearing Anopheles mosquitoes. The disease, which reproduces in red blood cells, proved fatal for white workers in the fields, and planters had trouble maintaining their crops. But they discovered that recently enslaved Africans had a degree of immunity to malaria because of the genetic condition sickle-cell anemia. Rice became a successful crop, followed by cotton, both tended by slaves.

Planters didn’t know what gave the enslaved Africans their ability to endure malaria. They assumed it was because they were genetically hardier. This was far from true; half of all Black children born into American slavery died before reaching the age of five.

Disease Was a Sign of American Success

At the time of the Revolution, Americans enjoyed far better health than their contemporaries in Europe. The average height — a good indication of the state of health — was 68.1 inches, just one inch lower than the average height today (the average European measured 65.76 inches). Roughly 60 percent of children raised in the country survived to age 60. (page 123, “Deadly Truth”)

According to The Deadly Truth: A History of Disease in America by Gerald N. Grob, almost all Americans of the early 1800s resided in the country, leading exceptionally healthy lives. They lived far apart, with little exposure to strangers bearing illnesses; they had healthy diets and a clean environment.

But the population began shifting toward the cities, according to Grob. Between 1800 and 1850, for instance, the population of Philadelphia increased 500 percent, consisting mostly of Americans leaving the country for the city. They were attracted by the commercial possibilities and the opportunity to enrich themselves beyond anything they could realize on a farm.

They came despite the already high risk of contracting a fatal disease in the city. Between 1721 and 1792, Boston was hit by seven epidemics. An outbreak of yellow fever in 1793 killed 1 in 10 Philadelphians.

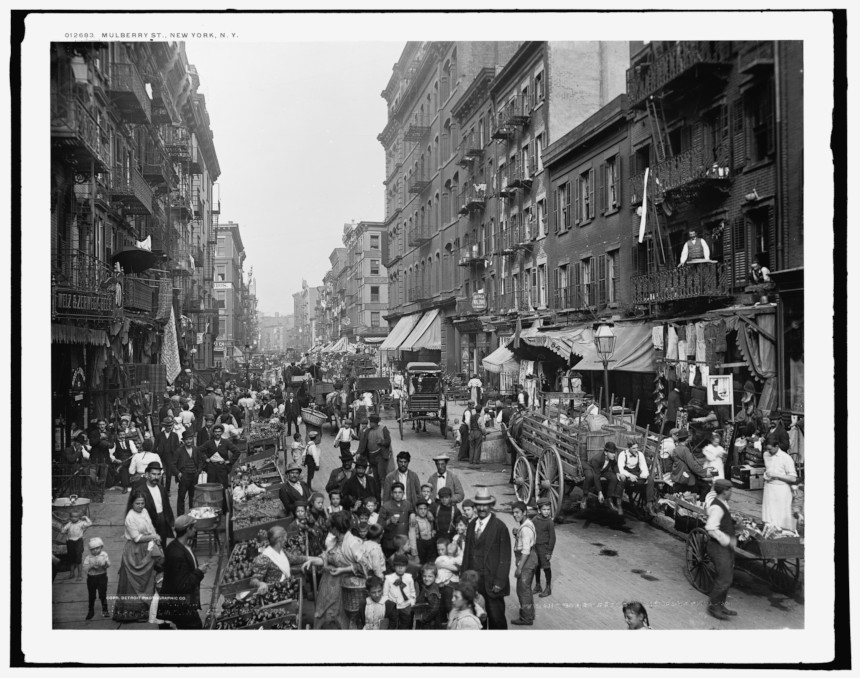

Urban crowding made disease transmission easier. Water supplies became contaminated. Immigrants, sailors, and visitors brought fresh injections of diseases. Cholera and yellow fever spread rapidly, and cities didn’t have the resources to care for the sick. In big cities like New York and Boston, only 16 percent of children reached their 60th birthday. By 1830, the average male height in America had fallen to under 67 inches.

A Mysterious Illness in Midwestern Livestock Began Emptying Towns

In the 1800s, settlers in the Ohio River Valley noticed livestock sometimes developed a trembling in their legs that soon led to collapse and death. Shortly afterward, their owners showed the same signs, as well as abdominal pains and vomiting. Farmers called it “milk sickness” and believed it was caused by an infectious agent.

The disease proved highly fatal in pioneer settlements, sometimes claiming up to half the residents. Areas of Kentucky and Illinois were especially hard hit. One of its victims was Abraham Lincoln’s mother.

The disease abated as the land became settled and animals began grazing in pasture land instead of the wilderness. It wasn’t until 1923 that Dr. Anna Pierce Hobbs Bixby learned from a Shawnee woman the cause of the sickness. Sheep and cattle were eating snake root, a member of the daisy family, which contains tremetol, a poison so strong it can kill animals and lethally poison its meat and milk. But in the days before it was discovered, the flow of settlers stayed away from areas where milk sickness was reported.

Another Disease Brought Prosperity to Colorado

America’s number-one killer in the 1800s was tuberculosis. Doctors didn’t understand its cause or course, but it seemed to be connected with damp, polluted air. So doctors advised TB patients to move to higher altitudes, where the air was dry and conditions sunny. The recommendation was partly useful. The decreased oxygen levels at high altitudes slowed the growth of the mycobacterium-causing organism. And the sunlight and fresh air was always good for patients.

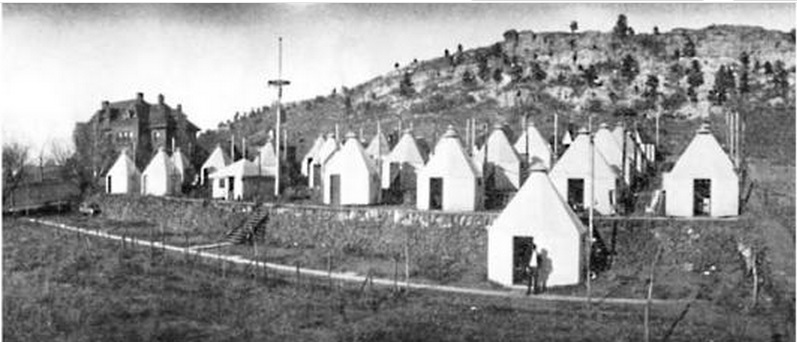

There were plenty of high altitudes and sunny weather in Colorado. Prior to the 1860s, it had been just another empty stretch of the western wilderness, sparsely peopled by miners and prospectors. But soon a growing number of sanitariums opened in Denver, Boulder, and Colorado Springs, and began to fill with tubercular patients. In time, they made up a third of the state’s population.

Cities grew up around the sanitariums, which attracted caregivers, support staff, and visitors to the patients. And TB patients often helped the town develop, bequeathing money to build streets and schools. In Denver alone, the population rose from 4,700 in 1870 to 106,000 in 1890.

Cleaning Up the Cities had Unintended and Fatal Consequences

Americans were shocked when a polio epidemic struck New England in 1916. For years, the incidence of the viral infections had declined almost to insignificance. Now, suddenly, 9,000 people had contracted the virus and 2,400 died — a fatality rate of 27 percent. The reason for the resurgence was completely unexpected.

Polio is caused by one of four viral strains. In the days before the Salk vaccine, most cases of polio ran their course in a day or two without serious complications. Only one case in 100 produced clinical symptoms, and even fewer caused paralysis. Most people experienced it as a low fever, headache, sore throat, and discomfort. But if the virus attacked the spine or the muscles controlling breathing, the consequences were quick and often fatal.

Up to the 1900s, most children in cities lived in crowded conditions and had been exposed to one of the strains at an early age. Or they gained immunity from maternal antibodies passed on to them as infants. Either way, most children growing up the congested cities were immune.

But as housing became less crowded and cleaner, there were fewer opportunities for exposure. A generation matured with little or no exposure and immunity. Polio swept through these communities quickly, striking down defenseless Americans. Franklin D. Roosevelt is a good illustration. He had grown up in wealth and comfort, and so had no immunity when the virus hit him in 1921 at the age of 39.

Featured image: Ward K, Armory Square Hospital, Washington, D.C., 1864 (Library of Congress)

A Letter from Sacramento, Where Fear Blooms as Flowers Grow

Our front garden hit peak bloom just as the COVID-19 death toll passed 200 in California. As usual, the California golden poppies seized control of the gravel borders along the driveway and, in a brazen move, advanced this spring into the chipped bark meant to provide walking space around the raised planter boxes. Now the last daffodils poke their heads out among the crimson flutter of the Greek poppies. The irises are flaunting wings and beards, each according to its wont, in random pairings around the yard. And the redbud is in full blossom on Mount Robin—the formal name for the mound of native plants my wife has let loose to the south of the front walk.

The garden has staged memorable spring performances before, though always to small audiences. We live four miles south of the State Capitol, well off the beaten path, on an eyebrow street just six houses long, connecting nothing to nowhere. Our hilly neighborhood of ranch houses was built without sidewalks in the early 1950s, when California planners were certain that walking was obsolete.

Weeks ago, back in normal times, only a few familiar souls would wander by. The dog walkers from the next block over. The slight blond teen walking bent, like a peasant woman carrying a bundle of firewood, under a backpack full of textbooks. The mother going to and from the nearby elementary school to retrieve her kids.

I haven’t seen the mother or the teenager since a substitute teacher at the elementary school died of COVID-19 and the schools shut down. But 13 days into the lockdown, as I sit in the garden to read on a sunny afternoon, what was once a trickle of walkers and bicyclists has broadened into a steady stream of people with nowhere else to go.

Many of the faces are new, and they arrive in family groups. The children are frisky and boisterous; the parents who trail them look like they’ve missed their naps. Some couples push baby strollers. Other couples push themselves, striding by fiercely to get the exercise they no longer get at the gym. In a role reversal, there are middle-aged children walking their elderly parents. The daughters tend to walk six feet to the side of the parent, letting them set the pace. The sons tend to lead, getting far out front, then pausing to let the parent shuffle within the prescribed distance before taking off again.

The irony here is that, for me, the social distancing that now fills our street is a social flowering. Coronavirus isn’t my first epidemic. In 1954, I was one of the 38,476 Americans paralyzed by polio.

There are lone walkers, too, talking loudly to their white headphones. One woman gestures with her hands, as if to make the decisive point in what may be a conference call in motion. In a few instances the person ambling up the street is someone we haven’t seen since a school committee meeting or a dinner party sometime in Bill Clinton’s first term.

Often people stop to admire the garden. We talk across the wide bed of Jupiter’s Beard, and I answer the horticultural questions if my wife is busy. The one with the tangerine flowers is mallow, I say, and behind it is the lupine, another native.

The irony here is that, for me, the social distancing that now fills our street is a social flowering. Coronavirus isn’t my first epidemic. In 1954, I was one of the 38,476 Americans paralyzed by polio. Sixty-six years later, in a wheelchair and no longer driving, I don’t get around much anymore. That’s especially true during flu season, when I try to stay away from the contagion. My “weak breathing muscles,” as my brother-in-law, the anesthesiologist, puts it, make me a good candidate to become a statistic again. Before the coronavirus arrived, I was fully trained for the loneliness Olympics, and in these recent early heats I haven’t yet had to break a sweat.

Until three months ago, I thought my 1954 epidemic experience had prepared me for the fear too.

I have only a few memories of those early days: Waking feverishly on the night the poliovirus took hold and then collapsing on the pink tile floor after my father carried me to the bathroom. Lying the next day on a hard table, under bright lights, in a mint-green operating room, to get the spinal tap that would confirm my illness. Being taken to an isolation room where everyone around me was shrouded in gowns and masks; even my parents were allowed no closer than the doorway. I don’t remember being scared. But I don’t doubt that it was fear that etched those memories into my consciousness.

The boy soon put the fear behind him. Today, the man he became isn’t as successful. The fear comes and goes in waves throughout the day. It follows me to bed in the evening, and it greets me in the morning when I open my eyes.

I am not alone in this.

“Did you sleep well?” I ask my wife.

“Yes,” she says, “but I had a dream about the grim reaper coming to the door to sell Girl Scout cookies.”

I do not fear for us. We have been physically distanced from the rest of the world for a month now. The virus is unlikely to breach our garden moat, not even in the guise of a Thin Mint, but I cannot hold out the images and news of the world around us.

I try to keep things in perspective.

You know from your reading, I tell myself soothingly, that folly and cupidity have marked every epidemic. Mom and dad went through the polio epidemics without losing their poise.

You’re right, I reply to myself. But would they have felt the same if people in their time were holding “polio parties”? And my parents probably took some comfort in having a president who was competent enough to organize and execute an invasion to destroy Nazi Germany.

Close the computer, I tell myself. Go to the garden. You’ll find calm and escape there.

Top of Form

So I pick up a book, roll through the front door and down the ramp. It’s warm and the air is thick with the mingled scents of the blossoms. I hear the footsteps of a jogger coming up the street. I look up and see her head emerge above the borage in the planter. She is wearing a mask. It’s the first I’ve seen.

I look over at the Greek poppies. I had it wrong. They aren’t fluttering, they’re trembling. And inside the incandescent red bowls blazing in the sun, there is a shadow.

Originally published at Zocalo Public Square.

Featured image: Shutterstock

America: 200 Years of Responding to Epidemics

To try and get a perspective on the current pandemic, many have compared it to the 1918-19 “Spanish flu” (which was actually an “American flu,” since it began in Kansas). While it was extraordinarily deadly, it wasn’t the only epidemic that has struck our country. But as Americans got smarter about controlling contagion, their epidemics became less deadly.

The first epidemic in the Americas was caused by smallpox, brought by European explorers and settlers. There are no numbers on the fatalities caused by this contagion, to which indigenous people had no resistance, but one estimate claims 80 percent of all native Americans were killed. Entire tribes vanished after contact with the new disease.

Colonial America knew the destructiveness of epidemics. In the 1660s, the bubonic plague had broken out in London, killing 100,000. To prevent a similar outbreak, Americans followed the European example of closing ports and quarantining ships in harbors until any contagious disease aboard would have died off.

When a ship left a port, its captain was usually furnished with a document called a bill of health. A ‘clean bill of health’ signified that the port from which the vessel sailed was free from infectious disease. A ‘touched’ bill indicates that there was a suspicion that disease was present, and a ‘foul’ bill shows that disease was raging in the port.

Ships without a clean bill of health had to lay at anchor in the harbor for up to 40 days, and no passengers or cargo were unloaded. No one is quite certain why the number 40 was chosen, but it was originally used by Venetians during the days of the Black Death. (From the Italian quaranta giorni comes “quarantine”.)

Even with precautions, epidemics entered America from its port cities.

In 1793, a group of 2,000 refugees fleeing the slave revolt in Haiti gathered at the port of Philadelphia. Somehow the bill-of-health system failed. Some passengers were already sick with yellow fever, and the ships had inadvertently brought infected mosquitoes — the source of the illness —in their holds.

The city responded to the illness by isolating the refugees and their belongings. But it was too late; the fever had already escaped into the city.

Philadelphia was then the nation’s capital, and when government officials saw the rising death toll, they took the hint and left the city. Those who remained tried to follow doctors’ advice to avoid contact with sick, and even each other. They also resorted to folk remedies. Men, women and children would smoke cigars constantly, believing this would ward off the “bad air” that carried the pestilence. Some Philadelphians had themselves bled — the presumed cure for almost everything in those days. They chewed garlic, or put it in their shoes. When outside they covered their noses and mouths with handkerchiefs soaked with vinegar or camphor. And they burned gunpowder, believing this would improve the oxygen in the atmosphere.

A Philadelphia publisher described the empty boulevards of the stricken city.

The coffee-house was shut up, as was the city library, and most of the public offices. Many never walked on the sidewalk, but went into the middle of the streets, to avoid being infected in passing houses wherein people had died.

Acquaintances and friends avoided each other in the streets, and only signified their regard by a cold nod. The old custom of shaking hands fell into such general disuse that many shrunk back with affright at even the offer of the hand. A person with any appearance of mourning was shunned like a viper. And many valued themselves highly on the skill with which they got windward of every person whom they met.

Over 5,000 Philadelphians died in this epidemic, nearly 20 percent of the city’s population.

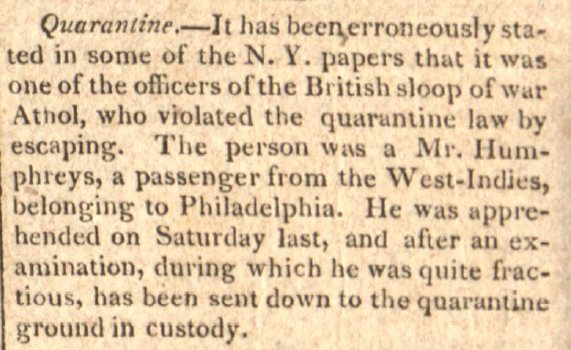

In 1832, a new contagion arrived in America: cholera. Ports were still quarantining any ship without a clean bill of health, but the lessons of past epidemics were being forgotten. Impatient passengers jumped ship or bribed the crew to put them ashore before the quarantine expired.

The Post reported incidents like these. From The June 28, 1823 issue, they noted the person who violated the quarantine law by escaping from the British sloop, Athol, “was a Mr. Humphreys, a passenger from the West Indies, belonging to Philadelphia. He was apprehended on Saturday last, and after an examination, during which he was quite fractious, has been sent down to the quarantine ground in custody.”

An item from the July 8, 1826, issue relayed, “A man about 30 years old was found on the shore near New Utrecht, New York, in a dying state. It was ascertained that he had been landed from on board a vessel arrived from Savannah, then lying at quarantine. As he died almost immediately after being discovered, the captain of the vessel was arrested.”

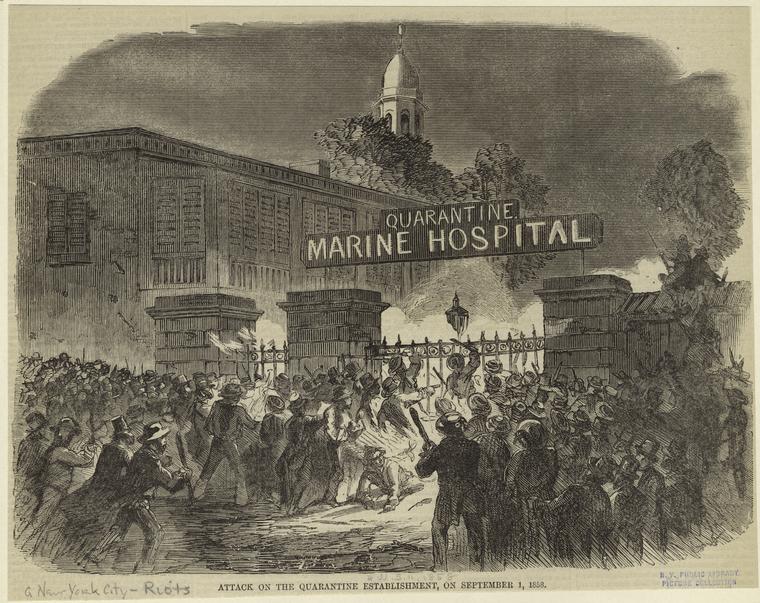

Many ports now disembarked passengers and isolated them in quarantine hospitals, nicknamed “pest houses.” One of America’s largest quarantine hospitals was located in New York harbor, on Staten Island. Residents of the island were unhappy that powerful contagions were contained close to their homes. In 1858, the islanders set fire to one of the hospital wards. On September 11, the Post reported its patients were hastily taken outside. “Some of the ill laid out of doors on the ground overnight, but on Thursday were placed inside of the only hospital left standing.”

The next night, the locals returned to burn down the remaining buildings, including the main hospital building. “At the time it was fired,” reported the Post, “it contained 125 patients, principally suffering from yellow fever, typhus, small-pox and other malignant diseases. It is presumed that many of these patients were burned to death.”

Eight years after the burning of the hospital, New York’s continued cruel treatment of epidemic victims prompted the Post editors to comment on the city’s harsh new law against cruelty to animals. They wrote in the May 19, 1866, issue, “What the New Yorkers need next is a law against cruelty to poor, sick, and dying humans — see N.Y. papers’ reports on quarantine doings.”

In 1878, an epidemic of yellow fever hit southern states. Memphis, TN, was struck particularly hard. Any resident in good health was advised to leave the city and head into the country. But residents in infected districts were forced to remain at home by mounted guards.

A doctor who’d seen yellow fever outbreaks around the world told the Post:

He has seen nothing to compare with the death-stricken aspect of Memphis at the present time. The wealthy have almost all departed, leaving the poor to shift as they may for themselves, and to the horrors of the plague are added those of a condition approaching to famine.

The banks are open only one hour a day. At night the streets are lit up with here and there the gleam of death fires, which burn in front of houses containing a corpse though not of every such house, for many a victim dies alone after suffering unattended, and there is no one to put out the customary signal. Persons taken sick on the streets crawl into unoccupied tenements and their corpses are afterwards discovered by the odor. The peculiar smell can be discerned at a distance of three miles.

By the next great epidemic, an outbreak of typhoid fever in 1906, medical science had a good idea of how the causative agent was being spread. Knowing the danger of contaminated water, New York had already begun building a modern sanitation system. But slow construction led to widespread typhoid infection, killing over 20,000 people.

1918 was the year of the great flu pandemic. The H1N1 virus swept around the world, infecting an estimated 500 million people — one third of all the people on earth. America suffered less than many countries because of precautions such as social distancing and face masks. Many public activities were postponed for months. Even with these measures, the flu killed an estimated 675,000 Americans. If America suffered a proportionally similar loss with today’s population, the death toll would be over two million.

The 1918 pandemic was something of a turning point. Up to that time, epidemics had usually caught America ill prepared. But with modern medicine and hygiene, epidemics lost much of their lethal power.

An epidemic of diphtheria occurred in the early 1920s and was responsible for 15,000 deaths. But an effective vaccine, developed in 1923, has brought the incidence of diphtheria so low, just two cases were reported between 2004 and 2017.

In 1942, America saw the incidence of polio climb to epidemic scope as the annual infection rate rose from 4,000 to 57,000 in ten years, with 3,145 deaths. But the incidence dropped sharply after the introduction of Dr. Salk’s vaccine in 1955. Now the CDC reports that America has been polio free since 1979.

And HIV was once a death sentence. Today over one million Americans are living with it, thanks to effective medical management.

Epidemics had lost the terror they formerly held for Americans, principally because we listened to medical experts and took their advice. With this new virus’s power, we’ll find out how well we have learned lessons from the pandemics of the past.

Featured image: A corpse is lifted from the back of a wagon during the 1832 cholera epidemic. Coloured lithograph, c. 1832. Credit: Wellcome Collection. Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0)

Your Health Checkup: What You Need to Know about Epidemics and Pandemics

My wife and I just received our annual flu shots along with a pneumonia vaccination for good measure.

As a physician — no, even as an average adult – the controversy surrounding vaccinations continues to astound me. Vaccination ranks as one of the all-time greatest medical breakthroughs, along with the discovery of antibiotics, statins and other innovative medical accomplishments. Yet, many people fail to take advantage of this simple life-saving technique Edward Jenner discovered in 1796. How parents can risk their children’s health and lives by refusing to have them vaccinated is beyond my comprehension. The myth that vaccination increases the risk of autism has long been disproven. Failure to vaccinate exposes the population to the threat of contracting measles, mumps, and other preventable diseases, as recent experience has shown.

Sadly, in many parts of the world and for many infections, preventive measures such as vaccinations don’t exist. Poorer countries often cannot adequately contain some infections because they lack basic primary health care or health infrastructure or have deep-seated distrust of health care services. These deficiencies raise the specter of a global pandemic; i.e., a disease that could spread from one country to many or even worldwide.

For example, the bubonic plague pandemic in the 14th century, the so-called Black Death, killed an estimated 50 million people, as did the influenza pandemic in 1918. It has been estimated that a contagion in the world today similar to the 1918 flu could kill as many as 80 million people and wipe out five percent of the global economy.

Modern examples of epidemics include Ebola infections in Western Africa (though, excitingly, a preventative vaccine may be on the horizon), severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS), and mosquito borne diseases like dengue, chikungunya, and Zika. Tick and mosquito borne illnesses have more than tripled in the U.S. since 2004. Eastern equine encephalitis (EEE) is an example of such a mosquito borne virus that appears to be on the rise with at least ten cases and two deaths noted in Massachusetts. EEE causes brain swelling with a 30 percent mortality. Health officials in Florida have issued an advisory about such mosquito borne illnesses, citing concern with all standing water containers such as bird baths, pools, and garbage cans in which mosquitos can breed, and advising people to keep skin covered with clothes and/or insect repellents when outside.

Population density and worldwide travel facilitate rapid transmission of such infections, as does global warming, which promotes mosquito growth and increases the risk of mosquito borne diseases. A panel of international experts concluded recently that the world is ill prepared to handle a pandemic of major magnitude. Control of insect and animal populations that harbor and spread these infections is critical and must be maintained despite political, weather, or other distractions. So must the level of vaccination. We cannot just increase efforts to contain a contemporary risk and then let our guard down when the risk diminishes.

My advice: do your part. Get vaccinated and make sure your children do as well.

Featured image: Shutterstock.