To try and get a perspective on the current pandemic, many have compared it to the 1918-19 “Spanish flu” (which was actually an “American flu,” since it began in Kansas). While it was extraordinarily deadly, it wasn’t the only epidemic that has struck our country. But as Americans got smarter about controlling contagion, their epidemics became less deadly.

The first epidemic in the Americas was caused by smallpox, brought by European explorers and settlers. There are no numbers on the fatalities caused by this contagion, to which indigenous people had no resistance, but one estimate claims 80 percent of all native Americans were killed. Entire tribes vanished after contact with the new disease.

Colonial America knew the destructiveness of epidemics. In the 1660s, the bubonic plague had broken out in London, killing 100,000. To prevent a similar outbreak, Americans followed the European example of closing ports and quarantining ships in harbors until any contagious disease aboard would have died off.

When a ship left a port, its captain was usually furnished with a document called a bill of health. A ‘clean bill of health’ signified that the port from which the vessel sailed was free from infectious disease. A ‘touched’ bill indicates that there was a suspicion that disease was present, and a ‘foul’ bill shows that disease was raging in the port.

Ships without a clean bill of health had to lay at anchor in the harbor for up to 40 days, and no passengers or cargo were unloaded. No one is quite certain why the number 40 was chosen, but it was originally used by Venetians during the days of the Black Death. (From the Italian quaranta giorni comes “quarantine”.)

Even with precautions, epidemics entered America from its port cities.

In 1793, a group of 2,000 refugees fleeing the slave revolt in Haiti gathered at the port of Philadelphia. Somehow the bill-of-health system failed. Some passengers were already sick with yellow fever, and the ships had inadvertently brought infected mosquitoes — the source of the illness —in their holds.

The city responded to the illness by isolating the refugees and their belongings. But it was too late; the fever had already escaped into the city.

Philadelphia was then the nation’s capital, and when government officials saw the rising death toll, they took the hint and left the city. Those who remained tried to follow doctors’ advice to avoid contact with sick, and even each other. They also resorted to folk remedies. Men, women and children would smoke cigars constantly, believing this would ward off the “bad air” that carried the pestilence. Some Philadelphians had themselves bled — the presumed cure for almost everything in those days. They chewed garlic, or put it in their shoes. When outside they covered their noses and mouths with handkerchiefs soaked with vinegar or camphor. And they burned gunpowder, believing this would improve the oxygen in the atmosphere.

A Philadelphia publisher described the empty boulevards of the stricken city.

The coffee-house was shut up, as was the city library, and most of the public offices. Many never walked on the sidewalk, but went into the middle of the streets, to avoid being infected in passing houses wherein people had died.

Acquaintances and friends avoided each other in the streets, and only signified their regard by a cold nod. The old custom of shaking hands fell into such general disuse that many shrunk back with affright at even the offer of the hand. A person with any appearance of mourning was shunned like a viper. And many valued themselves highly on the skill with which they got windward of every person whom they met.

Over 5,000 Philadelphians died in this epidemic, nearly 20 percent of the city’s population.

In 1832, a new contagion arrived in America: cholera. Ports were still quarantining any ship without a clean bill of health, but the lessons of past epidemics were being forgotten. Impatient passengers jumped ship or bribed the crew to put them ashore before the quarantine expired.

The Post reported incidents like these. From The June 28, 1823 issue, they noted the person who violated the quarantine law by escaping from the British sloop, Athol, “was a Mr. Humphreys, a passenger from the West Indies, belonging to Philadelphia. He was apprehended on Saturday last, and after an examination, during which he was quite fractious, has been sent down to the quarantine ground in custody.”

An item from the July 8, 1826, issue relayed, “A man about 30 years old was found on the shore near New Utrecht, New York, in a dying state. It was ascertained that he had been landed from on board a vessel arrived from Savannah, then lying at quarantine. As he died almost immediately after being discovered, the captain of the vessel was arrested.”

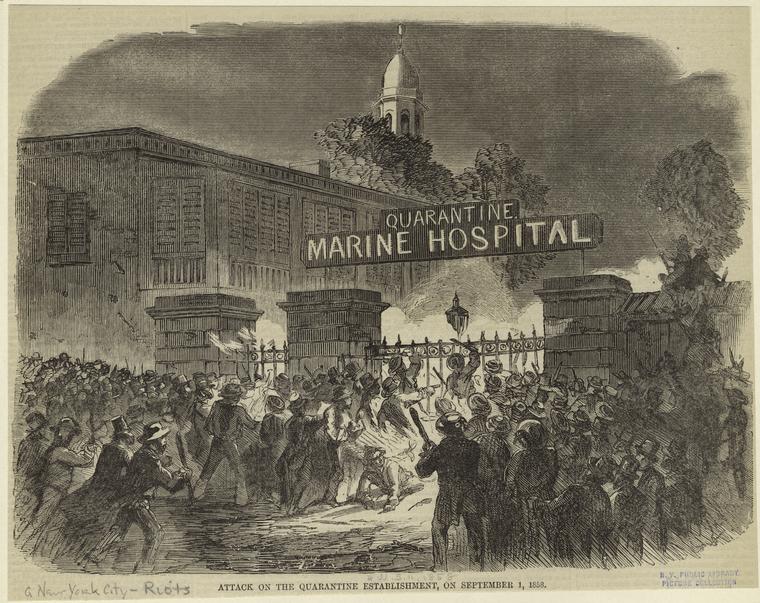

Many ports now disembarked passengers and isolated them in quarantine hospitals, nicknamed “pest houses.” One of America’s largest quarantine hospitals was located in New York harbor, on Staten Island. Residents of the island were unhappy that powerful contagions were contained close to their homes. In 1858, the islanders set fire to one of the hospital wards. On September 11, the Post reported its patients were hastily taken outside. “Some of the ill laid out of doors on the ground overnight, but on Thursday were placed inside of the only hospital left standing.”

The next night, the locals returned to burn down the remaining buildings, including the main hospital building. “At the time it was fired,” reported the Post, “it contained 125 patients, principally suffering from yellow fever, typhus, small-pox and other malignant diseases. It is presumed that many of these patients were burned to death.”

Eight years after the burning of the hospital, New York’s continued cruel treatment of epidemic victims prompted the Post editors to comment on the city’s harsh new law against cruelty to animals. They wrote in the May 19, 1866, issue, “What the New Yorkers need next is a law against cruelty to poor, sick, and dying humans — see N.Y. papers’ reports on quarantine doings.”

In 1878, an epidemic of yellow fever hit southern states. Memphis, TN, was struck particularly hard. Any resident in good health was advised to leave the city and head into the country. But residents in infected districts were forced to remain at home by mounted guards.

A doctor who’d seen yellow fever outbreaks around the world told the Post:

He has seen nothing to compare with the death-stricken aspect of Memphis at the present time. The wealthy have almost all departed, leaving the poor to shift as they may for themselves, and to the horrors of the plague are added those of a condition approaching to famine.

The banks are open only one hour a day. At night the streets are lit up with here and there the gleam of death fires, which burn in front of houses containing a corpse though not of every such house, for many a victim dies alone after suffering unattended, and there is no one to put out the customary signal. Persons taken sick on the streets crawl into unoccupied tenements and their corpses are afterwards discovered by the odor. The peculiar smell can be discerned at a distance of three miles.

By the next great epidemic, an outbreak of typhoid fever in 1906, medical science had a good idea of how the causative agent was being spread. Knowing the danger of contaminated water, New York had already begun building a modern sanitation system. But slow construction led to widespread typhoid infection, killing over 20,000 people.

1918 was the year of the great flu pandemic. The H1N1 virus swept around the world, infecting an estimated 500 million people — one third of all the people on earth. America suffered less than many countries because of precautions such as social distancing and face masks. Many public activities were postponed for months. Even with these measures, the flu killed an estimated 675,000 Americans. If America suffered a proportionally similar loss with today’s population, the death toll would be over two million.

The 1918 pandemic was something of a turning point. Up to that time, epidemics had usually caught America ill prepared. But with modern medicine and hygiene, epidemics lost much of their lethal power.

An epidemic of diphtheria occurred in the early 1920s and was responsible for 15,000 deaths. But an effective vaccine, developed in 1923, has brought the incidence of diphtheria so low, just two cases were reported between 2004 and 2017.

In 1942, America saw the incidence of polio climb to epidemic scope as the annual infection rate rose from 4,000 to 57,000 in ten years, with 3,145 deaths. But the incidence dropped sharply after the introduction of Dr. Salk’s vaccine in 1955. Now the CDC reports that America has been polio free since 1979.

And HIV was once a death sentence. Today over one million Americans are living with it, thanks to effective medical management.

Epidemics had lost the terror they formerly held for Americans, principally because we listened to medical experts and took their advice. With this new virus’s power, we’ll find out how well we have learned lessons from the pandemics of the past.

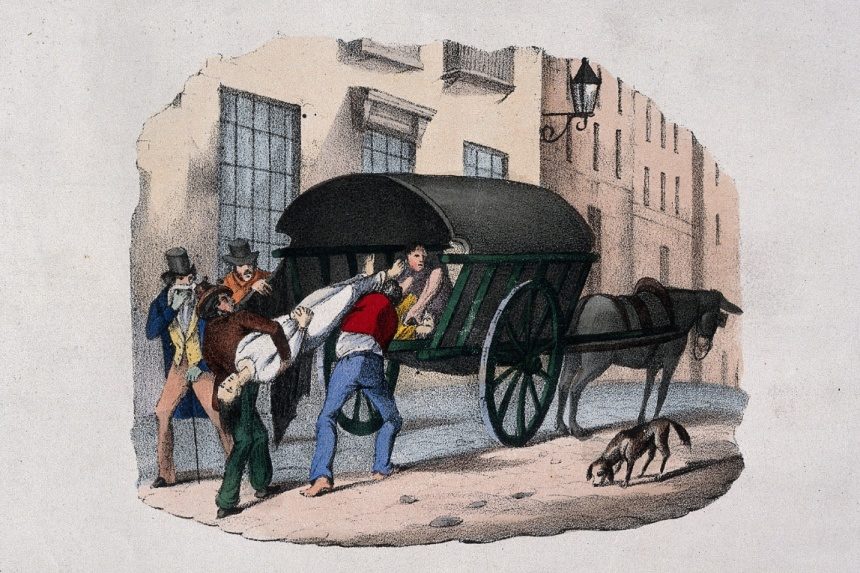

Featured image: A corpse is lifted from the back of a wagon during the 1832 cholera epidemic. Coloured lithograph, c. 1832. Credit: Wellcome Collection. Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0)

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

How interesting to note that in 1866 New York had passed laws against cruelty to animals but was indifferent to the sufferings of people with contagious diseases. It appears that things has not improved in the ensuing 150 years. Now we have New York passing a law protecting cats from being declawed because it is considered cruel and inhumane while indifferent to babies being killed in the womb.

Having been born in 1943, the only thing I remember about the polio epidemic was having my picture taken, getting a polio shot along with a classmate, which was published in The Hartford Courant. America was too busy dealing with WWII and then the era of “prosperity” in the ’50s while I was growing up. I don’t remember any of the hysteria that we have today…maybe some worry about becoming paralyzed. Guess the adults either didn’t pay much attention to it or shielded us kids from worrying about it. I imagine they didn’t feel there was much they could do about polio, so they went on about their lives. The most famous victim’s name associated with polio, of course, is Franklin D. Roosevelt.