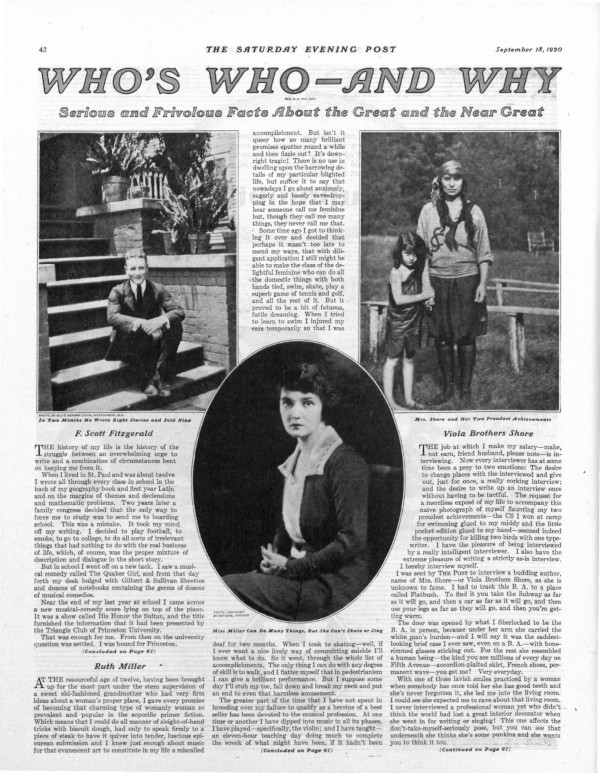

F. Scott Fitzgerald’s Rocky Start in Writing

Amidst the gleam of his emerging career, F. Scott Fitzgerald wrote a short personal essay for the Post’s “Who’s Who — and Why?” section letting the magazine’s readers in on where this new writer had come from. The year, 1920, had been a momentous one for Fitzgerald, having published his first novel, This Side of Paradise, along with several short stories: first, “Head and Shoulders,” and “The Ice Palace,” and later the famous “Bernice Bobs Her Hair.” The “jazz age” author offers distant comments on his life hitherto as though it were all an ironic dream leading him to inevitable success. Fitzgerald would muse about his own life for the magazine many more times in the years to come, penning “How to Live on $36,000 a Year” in 1924 and “One Hundred False Starts” in 1933.

Originally Published on September 18, 1920

The history of my life is the history of the struggle between an overwhelming urge to write and a combination of circumstances bent on keeping me from it.

When I lived in St. Paul and was about twelve I wrote all through every class in school in the back of my geography book and first year Latin and on the margins of themes and declensions and mathematic problems. Two years later a family congress decided that the only way to force me to study was to send me to boarding school. This was a mistake. It took my mind off my writing. I decided to play football, to smoke, to go to college, to do all sorts of irrelevant things that had nothing to do with the real business of life, which, of course, was the proper mixture of description and dialogue in the short story.

But in school I went off on a new tack. I saw a musical comedy called The Quaker Girl, and from that day forth my desk bulged with Gilbert & Sullivan librettos and dozens of notebooks containing the germs of dozens of musical comedies.

Near the end of my last year at school I came across a new musical comedy score lying on top of the piano. It was a show called His Honor the Sultan, and the title furnished the information that it had been presented by the Triangle Club of Princeton University.

That was enough for me. From then on the university question was settled. I was bound for Princeton.

I spent my entire Freshman year writing an operetta for the Triangle Club. To do this I failed in algebra, trigonometry, coordinate geometry, and hygiene. But the Triangle Club accepted my show, and by tutoring all through a stuffy August I managed to come back a Sophomore and act in it as a chorus girl. A little after this came a hiatus. My health broke down and I left college one December to spend the rest of the year recuperating in the West. Almost my final memory before I left was of writing a last lyric on that year’s Triangle production while in bed in the infirmary with a high fever.

The next year, 1916-17, found me back in college, but by this time I had decided that poetry was the only thing worthwhile, so with my head ringing with the meters of Swinburne and the matters of Rupert Brooke I spent the spring doing sonnets, ballads and rondels into the small hours. I had read somewhere that every great poet had written great poetry before he was 21. I had only a year and, besides, war was impending. I must publish a book of startling verse before I was engulfed.

By autumn I was in an infantry officers’ training camp at Fort Leavenworth, with poetry in the discard and a brand new ambition—I was writing an immortal novel. Every evening, concealing my pad behind Small Problems for Infantry, I wrote paragraph after paragraph on a somewhat edited history of me and my imagination. The outline of 22 chapters, four of them in verse, was made, two chapters were completed; and then I was detected and the game was up. I could write no more during study period.

This was a distinct complication. I had only three months to live — in those days all infantry officers thought they had only three months to live — and I had left no mark on the world. But such consuming ambition was not to be thwarted by a mere war. Every Saturday at one o’clock when the week’s work was over I hurried to the Officers’ Club, and there, in a corner of a roomful of smoke, conversation and rattling newspapers, I wrote a one-hundred-and-twenty-thousand-word novel on the consecutive weekends of three months. There was no revising; there was no time for it. As I finished each chapter I sent it to a typist in Princeton.

Meanwhile I lived in its smeary pencil pages. The drills, marches and Small Problems for Infantry were a shadowy dream. My whole heart was concentrated upon my book.

I went to my regiment happy. I had written a novel. The war could now go on. I forgot paragraphs and pentameters, similes and syllogisms. I got to be a first lieutenant, got my orders overseas — and then the publishers wrote me that though The Romantic Egotist was the most original manuscript they had received for years they couldn’t publish it. It was crude and reached no conclusion.

It was six months after this that I arrived in New York and presented my card to the office boys of seven city editors asking to be taken on as a reporter. I had just turned 22, the war was over, and I was going to trail murderers by day and do short stories by night. But the newspapers didn’t need me. They sent their office boys out to tell me they didn’t need me. They decided definitely and irrevocably by the sound of my name on a calling card that I was absolutely unfitted to be a reporter.

Instead I became an advertising man at 90 dollars a month, writing the slogans that while away the weary hours in rural trolley cars. After hours I wrote stories — from March to June. There were 19 altogether; the quickest written in an hour and a half, the slowest in three days. No one bought them, no one sent personal letters. I had 122 rejection slips pinned in a frieze about my room. I wrote movies. I wrote song lyrics. I wrote complicated advertising schemes. I wrote poems. I wrote sketches. I wrote jokes. Near the end of June I sold one story for 30 dollars.

On the Fourth of July, utterly disgusted with myself and all the editors, I went home to St. Paul and informed family and friends that I had given up my position and had come home to write a novel. They nodded politely, changed the subject and spoke of me very gently. But this time I knew what I was doing. I had a novel to write at last, and all through two hot months I wrote and revised and compiled and boiled down. On September 15th This Side of Paradise was accepted by special delivery.

In the next two months I wrote eight stories and sold nine. The ninth was accepted by the same magazine that had rejected it four months before. Then, in November, I sold my first story to the editors of The Saturday Evening Post. By February I had sold them half a dozen. Then my novel came out. Then I got married. Now I spend my time wondering how it all happened.

In the words of the immortal Julius Caesar: “That’s all there is; there isn’t anymore.”

Featured image: The Saturday Evening Post, September 18, 1920

Top 10 Late Spring Reads

Every month, Amazon staffers sift through hundreds of new books searching for gems. Here’s what Amazon editor Chris Schluep chose especially for Post readers this spring.

Fiction

Into the Water

by Paula Hawkins

The author of the mega-hit The Girl on the Train is back with more psychological suspense in this new novel about a town and a river that hold forgotten secrets — plus a few discarded bodies.

Riverhead Books

Camino Island

by John Grisham

Taking time off from publishing legal thrillers, Grisham has written a cat-and-mouse beachside caper about stolen F. Scott Fitzgerald manuscripts. This is a great read by a master of his craft.

Doubleday

Since We Fell

Since We Fell

by Dennis Lehane

The Shutter Island author’s latest is the story of a life and a marriage unraveling as a woman is drawn into a conspiracy that she didn’t go looking for and might not have the strength to escape.

Ecco

The Ministry of Utmost Happiness

The Ministry of Utmost Happiness

by Arundhati Roy

From the Booker Award-winning author of The God of Small Things comes a tale of intertwined characters in search of meaning, love, and safety against the backdrop of the Indian subcontinent.

Knopf

The Identicals

The Identicals

by Elin Hilderbrand

Old grudges bubble to the surface as identical twins struggle to confront a family crisis. The twins are so alike and yet so different, and they must decide which distinction matters more.

Little, Brown and Co.

Nonfiction

Astrophysics for People in a Hurry

Astrophysics for People in a Hurry

by Neil deGrasse Tyson

Even if you’ve never hoped you could understand the nature of space and time, Neil deGrasse Tyson answers the questions of the cosmos in a witty and easily digestible style that keeps you turning pages.

W.W. Norton

How to Be a Stoic

How to Be a Stoic

by Massimo Pigliucci

Stoicism is hot right now, and in this book, Pigliucci argues that the ancient philosophy that has long been associated with suffering is really about learning how to differentiate what you can, and can’t, control in your life.

Basic Books

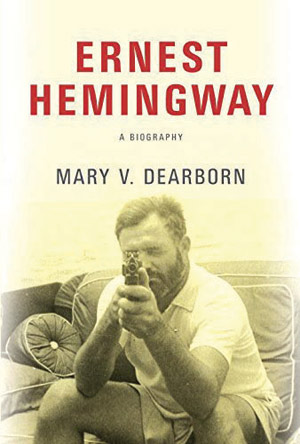

by Mary V. Dearborn

This is the first biography of Hemingway in 15 years — and the first written by a woman. It draws on new material to give the richest and most nuanced portrait yet of one of America’s greatest writers.

Knopf

Theft by Finding

Theft by Finding

by David Sedaris

Drawn from decades of diary entries, Sedaris’ latest collection reveals a unique view of the world from a man who turned a grim start as a drug-abusing dropout into a funny, generous, and uncomfortable career as one of our greatest modern observers.

Little, Brown and Co.

Upstream

Upstream

by Langdon Cook

Through an exploration of the natural history of his subjects, Cook sets readers at the essential intersection of man, food, and nature in a portrait of the all-important salmon and the places where and people to whom salmon matter most.

Ballantine Books

News of the Week: Grease Theories, Greta Friedman, and the Great Guacamole Controversy

Here’s a Theory About Grease I Bet You Never Thought Of

Of course, you probably don’t sit around your house thinking about Grease theories at all — “Hey, Edna! Get in here! I have a new theory about Grease I want to share with you!” — but if you did, here’s a new one that might interest you.

Sandy was dead the whole time! [insert scary music here]

This theory was spread by actress Sarah Michelle Gellar on Facebook. She didn’t come up with it, but she heard about it and passed it along to her fans.

That’s right, Sandy actually drowned at the beach that day (“I saved her life, she nearly drowned …”) and she’s in a coma imagining this entire musical before she dies. Grease co-creator Jim Jacobs disputes this theory, though to be accurate, he co-created the stage musical. This theory has to do with the 1978 movie version with John Travolta and Olivia Newton-John.

If anything, this new theory might give you an idea for a Halloween costume this year. Sure, many people will be dressing up as Donald Trump or Hillary Clinton or Captain America or someone from Game of Thrones, but you can surprise everyone by going as Dead Sandy from Grease. Just be prepared for a lot of questions.

RIP Greta Zimmer Friedman

Friedman is one of the most famous women in the world, but you never knew her name.

She was the dental assistant grabbed and kissed by a sailor in Times Square on V-J Day, the day World War II ended in 1945. Friedman was just standing there with friends celebrating when George Mendonsa, a sailor also celebrating the end of the war, surprised her by taking her in his arms and kissing her. The classic photo was taken by Alfred Eisenstaedt.

Friedman passed away last week at the age of 92. She’s going to be buried at Arlington National Cemetery next to her husband.

There has actually been confusion about who the couple was, with several other people coming forward over the years, claiming to be the man and woman in the photo. But researchers say that Mendonsa and Friedman are the ones locking lips in the iconic picture, and four years ago CBS reunited the couple in Times Square.

Squee, Moobs, and YOLO

No, that isn’t the title of a new kids cartoon about animals who open a law firm. They’re three words that have been added to the Oxford English Dictionary.

Squee is the high-pitched sound someone makes when they’re excited. YOLO is an acronym for “You Only Live Once,” and moobs is a pudgy man’s … well, you can Google that if you want.

Other new words added include Murica (a different way of saying “America,” and it has more than one spelling), clickbait (those web headlines that try to get you to click on them and they turn out to be misleading or worse), and fuhgeddaboutit (“forget about it” mashed into one word and often said by people in New Jersey). To celebrate Roald Dahl’s 100th birthday, the OED editors have also added Oompa Loompa and scrumdiddlyumptious, and they’re also adding yogalates, which is a combo of yoga and pilates. Like you, this is the first time I’ve ever heard that word.

By the way, if you can use all of those words in a single sentence, let us know in the comments.

New F. Scott Fitzgerald Stories Coming in 2017

Who said there are no second acts in American lives? Oh wait, that was F. Scott Fitzgerald. But he might change his tune if he were alive today.

Next April, Scribner will release I’d Die For You, a collection of stories Fitzgerald wrote in the 1930s and was unable to sell because the subject matter was different from what magazine editors at the time expected of the writer. The title comes from the time Fitzgerald was suffering from alcoholism in North Carolina and his wife was in a sanatorium.

Fitzgerald, of course, wrote several classic stories for The Saturday Evening Post, and here’s a feature on how we helped create The Great Gatsby.

This Week in History: Jesse Owens Born (September 12, 1913)

Owens wrote several pieces about the Olympics for The Saturday Evening Post in 1976, including this piece on how he trained for the 1936 Olympics in Berlin and what happened there.

This Week in History: Princess Grace of Monaco Dies (September 14, 1982)

Here’s how Princess Stephanie, youngest daughter of Princess Grace, described the car accident that took the life of the former actress known as Grace Kelly.

National Guacamole Day

How many ways are there to make guacamole? You’re probably thinking that guacamole can’t possibly be controversial. But it is, and we’ll get to that in a minute. Meanwhile, for National Guacamole Day (which is today), here’s a classic recipe from The Saturday Evening Post Antioxidant Cookbook.

You’ll notice that this recipe — like most guacamole recipes — doesn’t have peas in it. And therein lies the controversy. Last year, people were up in arms because The New York Times printed a guacamole recipe that included those little green veggies. It was The Great Green Pea Scandal of 2015! The Guacamole Recipe That Shook the World! The Guacamole Conundrum (which also happens to be the best Robert Ludlum novel)!

Here’s the recipe that caused all the trouble. Even if you don’t think it sounds too appetizing, try it anyway. Maybe you’ll be surprised. YOLO!

Next Week’s Holidays and Events

The Emmy Awards (September 18)

The 68th ceremony airs this Sunday at 7 p.m. Eastern on ABC. Here’s a list of nominees so you can make your guesses at home.

Wife Appreciation Day (September 18)

Not to be confused with Mother’s Day, which celebrates women with children. Wife Appreciation Day is for married women who don’t have kids.

Fall begins (September 22)

BREAKING NEWS: I bought tea this week; I’m ready for fall. That doesn’t mean the temperatures are going to cooperate right away, but fall begins on the 22nd, and I’m ready for it.

News of the Week: Goodbye Jon Stewart, Hello F. Scott Fitzgerald, and Happy Birthday to You

Goodbye Jon Stewart

s_bukley / Shutterstock.com

Wait, that makes it sound like he died. I just mean that last night’s episode of The Daily Show was the last one for host Jon Stewart, after hosting the show for 16 years. Stewart’s final guests were Amy Schumer, Denis Leary, and Louis CK, along with some surprise guests to celebrate Stewart’s tenure on the show, the show that made Stephen Colbert and Steve Carell household names.

Everyone is celebrating the departing host this week, with retrospectives and best-of lists and essays. Time’s James Poniewozik reveals what he’ll miss most about Stewart. The Wall Street Journal’s Speakeasy blog has a rundown of some of his more odd guests. Newsweek delves into the comic and crusader parts of The Daily Show , and and the show itself showcased some of the craziest interviews earlier this week. Note: some NSFW moments in that last link.

What will Stewart do now? Don’t expect him back on television anytime soon. I would think he’s going to write more, direct more, and maybe even do more standup. He did a surprise gig at Comedy Cellar in New York City last week with Louis CK. I was just going to call him “CK” but that doesn’t sound right.

Trevor Noah takes over as host of The Daily Show on September 28. I think it would have been funny to have Craig Kilborn return as host. He hosted the show before Stewart, and on Stewart’s first night he said that Kilborn was on assignment in Kuala Lampur. It would have been great to have Kilborn finally come back from that assignment to resume hosting duties again.

New F. Scott Fitzgerald Story Published

The discovery of new works by writers continues! Now we have a long-lost short story by F. Scott Fitzgerald. It’s called “Temperature,” and it’s about a writer who drinks a lot and then finds out he’s sick. And before you even make a joke about how art imitates life, Fitzgerald beat you to it. He says at the beginning of the story, “And as for that current dodge ‘no reference to any living character is intended’ -no use even trying that.” He wrote it in the summer of 1939, when he was hospitalized twice for alcoholism. (According to a letter Fitzgerald wrote his agent, he submitted the story to The Saturday Evening Post, and it was rejected. Sorry, Mr. Fitzgerald!)

The story is in the current issue of the magazine The Strand. The managing editor of the magazine, Andrew Gulli, found the manuscript while he was looking at the Fitzgerald archives at Princeton.

So besides Fitzgerald, we’ve also had new works from Harper Lee, Dr. Seuss, Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, Raymond Chandler, Orson Welles, and probably a few others I’ve forgotten about. Quick, someone check Dorothy Parker’s attic!

Happy Birthday to You

Have you ever sang “Happy Birthday to You” at a party? Then you probably owe someone some money.

Yup, that’s a copyrighted song, even if it is sung 57 bajillion times a day (a conservative estimate). Like every other “cover song,” you’re supposed to pay to sing it. Warner/Chappell is the publisher and they make around $2 million in royalties from it every year. The song, originally titled “Good Morning to You,” was written by two sisters in 1893.

But now there’s a lawsuit (there’s always a lawsuit) brought by a filmmaker who wanted to use the song in her movie but was told she had to pay $1,500. She wants everyone to be able to use the song free of charge because it’s in “the public domain” and everyone sings it. It all comes down to when the “happy birthday” lyrics were added to the song. A federal judge will rule on it later this month.

By the way, even if you’re singing the song only in your head right now, you owe some money.

It’s Official: Kermit and Miss Piggy Have Broken Up

Jaguar PS / Shutterstock.com

This has been a big couple of weeks for celebrity breakups. Reba McEntire and her husband are divorcing after 26 years of marriage. Country stars Blake Shelton and Miranda Lambert are also going their separate ways, as are rockstar couple Gwen Stefani and Gavin Rossdale. But the most shocking split comes from two celebrities that aren’t even human.

Kermit and Miss Piggy are no longer dating. The frog and pig announced the breakup during a Q&A session at the annual Television Critics Association get-together, where they were promoting ABC’s update of The Muppets, which will debut this fall. Kermit said that Miss Piggy made his life “a bacon-wrapped hell on Earth.”

If these two can’t make it work…

And the Highest Paid Actor in the World Is…

Featureflash / Shutterstock.com

…Ian Ziering, star of the Sharknado movies. I know, I was surprised too!

Okay, that’s not true. The highest-paid actor in the world – for the third year in a row – is Robert Downey Jr., according to the annual list compiled by Forbes. Thanks to all of the superhero movies he’s doing, he raked in $80 million last year. Second on the list is Jackie Chan, with $50 million, followed by Vin Diesel ($47 million), Bradley Cooper ($41.5 million), and Adam Sandler ($41 million).

Adam Sandler. One of the richest movie stars in the world.

August is National Sandwich Month

I usually provide a few links to recipes in this section, but how do you do that with sandwiches? There are literally thousands, if not millions, of different sandwiches a person can make, depending on the bread you use, the filling, whether you toast it or not, etc. So instead why don’t I provide a link to something and you can all get into an argument?

Here’s a list from Thrillist that lists the 50 best sandwiches of all-time. Let me just say that number 36 should be a lot higher. And I’m sure that some people are going to question why a hamburger wasn’t considered – because it’s not a sandwich – but “hamburger sub” is on the list because they took the burgers and shoved them into a sub roll. And peanut butter and jelly, one of the classic sandwiches of all-time, should be in the top 10, not 26.

By the way, as we all know, the sandwich was named after the man who invented it, Alexander Hoagie.

Upcoming Events and Anniversaries

The Smithsonian Institution established (August 10, 1846)

A lot of people might think the Smithsonian is just one museum, but it’s so much more.

Victory Day (August 10)

Did you know this once federal holiday is now only celebrated in Rhode Island?

Alfred Hitchcock born (August 13, 1899)

The BBC recently released their list of the 100 Greatest American Films and Hitchcock grabbed several of the spots. But come on: everyone knows North By Northwest is better than Psycho.

Berlin Wall construction begins (August 13, 1961)

USA Today has 9 things you might not know about the fall of the wall.

Steve Martin born (August 14, 1945)

Check out the scary hand on his official site.

Woodstock opens (August 15, 1969)

The official title for the event was The Woodstock Music & Art Fair, though no one really talks about the art.

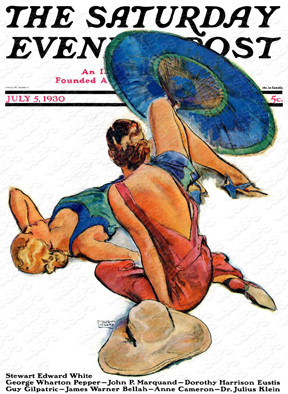

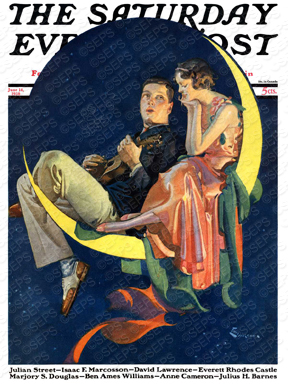

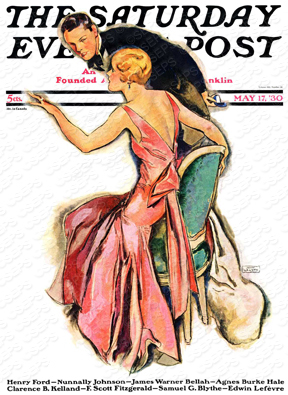

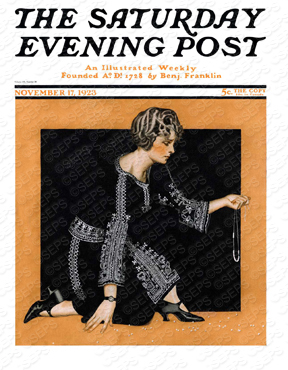

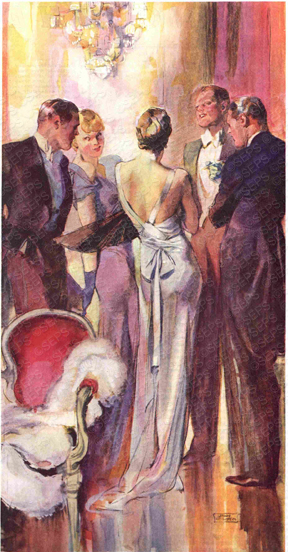

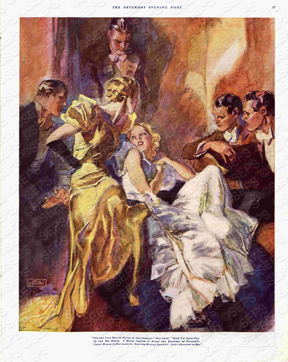

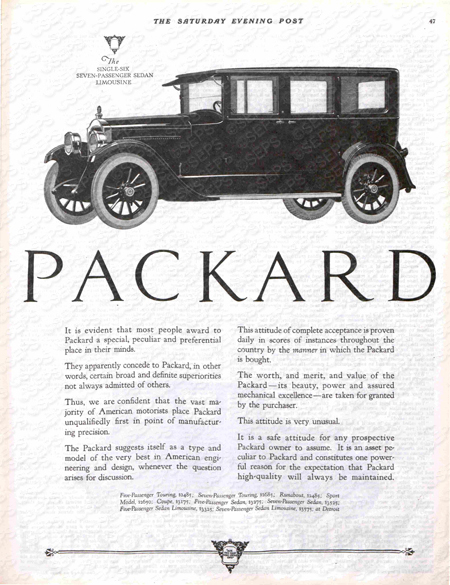

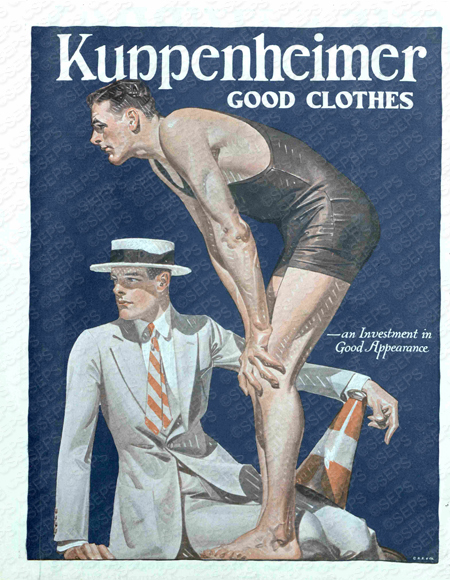

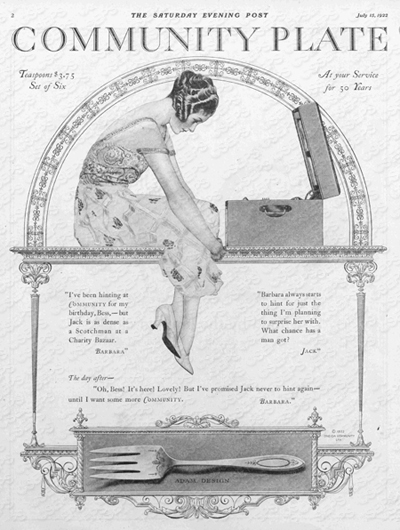

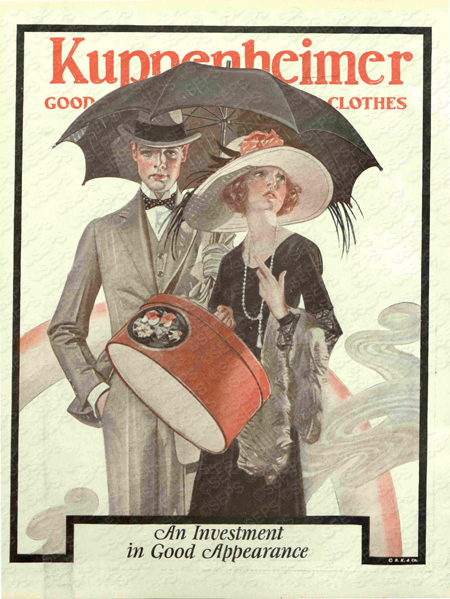

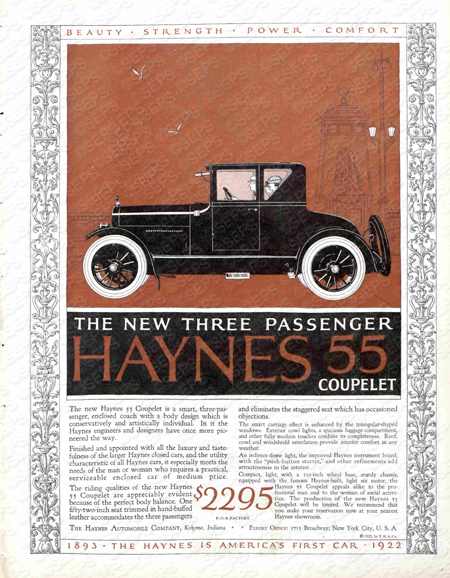

Vintage Gatsby-Era Art

Before he penned The Great Gatsby, F. Scott Fitzgerald earned his fame and wealth from short stories he wrote for The Saturday Evening Post. His earnings brought the lavish parties, flapper culture, and glittering jazz of the Roaring ’20s to life.

Here’s a look at some of the Post‘s Gatsby-era artwork. For more original illustrations and beautiful cover images, check out Gatsby Girls, available for purchase in print and digital editions.

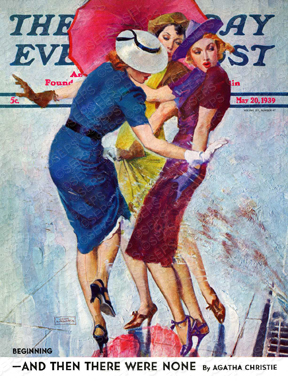

John LaGatta

May 20, 1939

John LaGatta

January 6, 1934

Illustration by Thomas Webb

The Saturday Evening Post

August 6, 1932

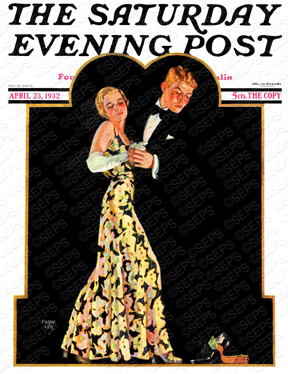

Frank Lea

April 23, 1932

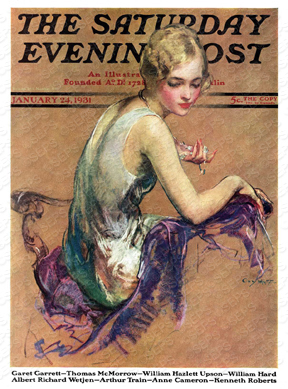

Guy Hoff

January 24, 1931

John LaGatta

July 5, 1930

E.M. Jackson

June 14, 1930

John LaGatta

May 17, 1930

Coles Phillips

November 17, 1923

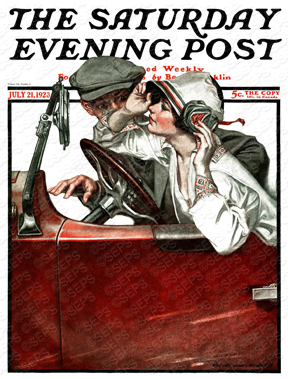

Walter Beach Humphrey

July 21, 1923

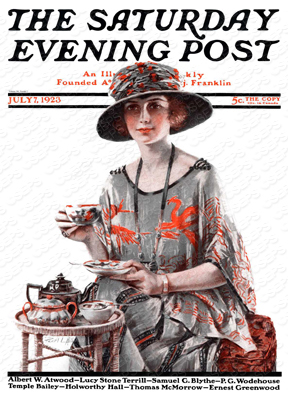

Pearl L. Hill

July 7, 1923

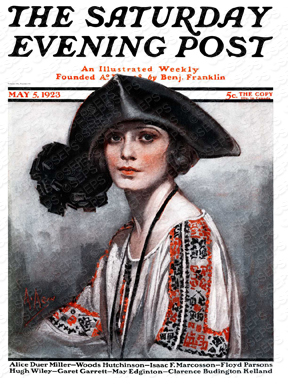

Neysa McMein

May 5, 1923

Neysa McMein

March 3, 1923

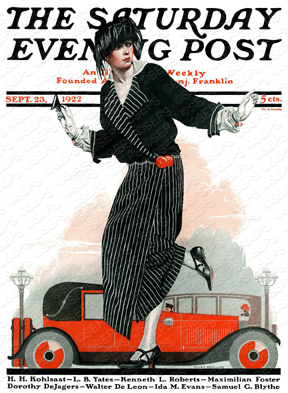

Coles Phillips

September 23, 1922

Coles Phillips

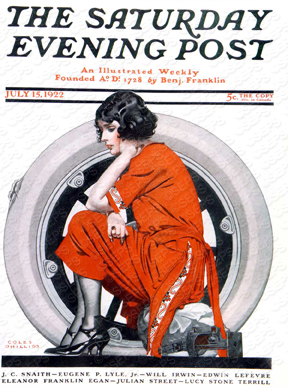

July, 15 1922

Illustration by John LaGatta

The Saturday Evening Post

March 4, 1933

by Marian Spitzer

Illustration by John LaGatta

The Saturday Evening Post

December 10, 1932

The Saturday Evening Post

December 23, 1922

The Saturday Evening Post

September 16, 1922

The Saturday Evening Post

August 12, 1922

The Saturday Evening Post

July 15, 1922

The Saturday Evening Post

April 22, 1922

The Saturday Evening Post

April 1, 1922

The Saturday Evening Post

February 25, 1922

The Saturday Evening Post

February 18, 1922

Illustrated by Frank X. Leyendecker

The Saturday Evening Post

January 28, 1922

How The Saturday Evening Post Helped Create Gatsby

In 1918, an ambitious young man from the Midwest traveled south to an army training camp. He was hoping to become an officer, get posted to France, and earn fame and promotion on the Western Front. But the First World War ended before he could distinguish himself.

The trip south wasn’t a complete waste, however, because he found the love of his life: a charming and strong-willed Southern belle. The two fell in love, but the girl refused to marry him because he didn’t have enough money. So he set out to earn the fortune that would win his fiancée back to him.

Up to this point, the story describes the early career of both the fictional Jay Gatsby and his creator, F. Scott Fitzgerald. Gatsby eventually went to work for bootleggers. Fitzgerald returned home to Minnesota and threw himself into writing. Within a year, his career took off when he was discovered by both a book publisher and the editors of The Saturday Evening Post.

In April 1920, Scribner published his first novel, This Side of Paradise. The book was an immediate success; the entire first edition of 60,000 copies sold out within three days.

But even before the novel hit bookstores, the Post was publishing his short stories. Years later, he recalled his excitement at the news of the Post accepting his work: “I’d like to get a thrill like that again but I suppose it’s only once in a lifetime.” The Post’s editors liked his work and published six of his stories in 1920 alone.

Any writer published in the Post during the 1920s would have felt that he or she had ‘arrived.’ No other magazine offered such a large audience—2.5 million readers—or such large payments. Even though he was still an unproven author, Fitzgerald received $400 for his first story. Within a year, the editors had increased his fee to $500. By 1929, they were paying him $4,000 for every story, which would be, roughly, $54,000 today. He began to live extravagantly, spending money as if it would always come as quickly and as easily.

He never again enjoyed the success with a novel as he did with his first. For the rest of his 20-year career, the majority of his income came from short stories—168 of them. And most of this money came from the Post, which published 65 of his stories between 1920 and 1937.

Fitzgerald knew that writing would win him the recognition and success he needed. It would enable him to live like the wealthy students he’d met at Princeton: young men with carefree, careless manners and a natural assumption of privilege and preference. His new wealth also helped convince that charming Southern belle, Zelda Sayre, to marry him. And so, with the Post’s money burning a hole in the pocket of his raccoon coat, Fitzgerald and his free-spending wife began a spree of lavish living that continued through the decade.

His earnings introduced him to the world of Gatsby. He entered a nonstop party, surrounded by the sounds of hot jazz and an ocean of bootleg liquor that extended from nightclubs to exclusive New York hotels. He moved into an exclusive area on Long Island, New York, and eventually relocated to France, where he spent his time among wealthy American émigrés in Paris and the French Riviera.

This new life brought him into close contact with the wealthy, including aimless young people with inherited fortunes. He began to see the emptiness that often lay at the heart of success and the dark edges of the Great American Dream.

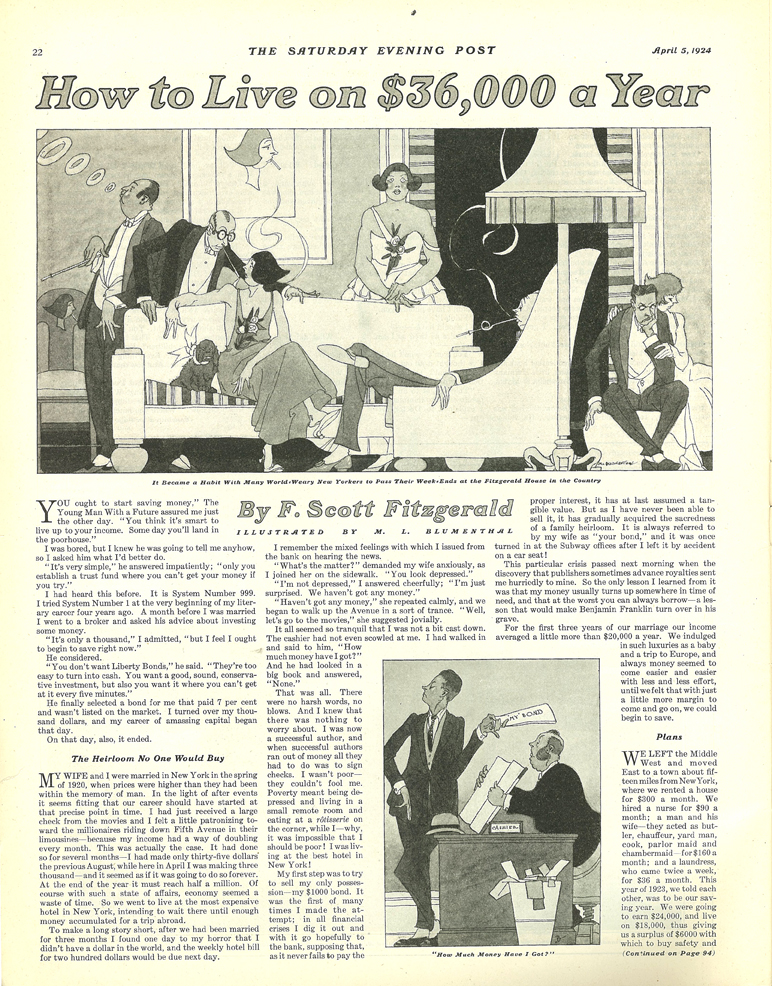

Like Gatsby, Fitzgerald entertained lavishly and continually, spending money on a scale that’s hard to imagine. In 1924, he wrote an article for the Post entitled “How To Live on $36,000 a Year.” It is a humorous piece describing the ineffectual attempts he and his wife made to live within a budget. He wrote it after he realized that, in a single year, he’d burned through the 2013 equivalent of half a million dollars. A few months later, the Post published “How To Live On Practically Nothing A Year,” which told how he moved to Europe where he could live comfortably for far less money. But even with a favorable exchange rate, he had trouble keeping ahead of his spending.

He completed The Great Gatsby while living in France. It is perhaps his greatest work: concise, intriguing, and peopled with memorable characters. Like all his works, it is beautifully written, created by a great writer at the height of his powers. Fitzgerald built his stories with the precision and care of a master jeweler. There is not one wasted or poorly chosen word, or one flabby sentence in its 200 pages.

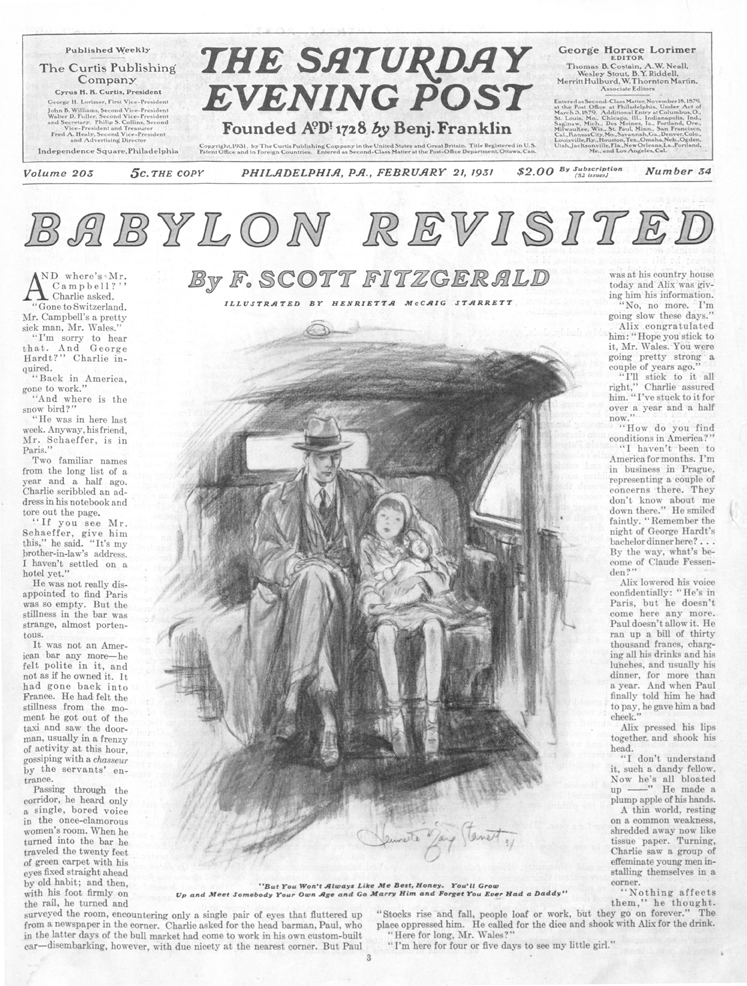

He wanted to write more novels, but he never escaped money problems. As long as the Post continued to pay him so well, he continued writing stories for its pages. Though they weren’t novels, Fitzgerald was proud of his talent for producing these “commercial” pieces. He knew writing magazine fiction was far more difficult than it looked, and he was good at it. His Post stories contain some of his finest, most readable works: “Bernice Bobs Her Hair,” “The Last Belle,” “Babylon Revisited,” “The Ice Palace,” and all the Basil and Josephine stories.

His work for the Post didn’t give him the satisfaction he got from writing The Great Gatsby, which he told a friend was “about the best American novel ever written.” But without the support of the Post, Gatsby would never have been born.

Read F. Scott Fitzgerald’s stories in Gatsby Girls, a collection of his first eight short stories originally published in The Saturday Evening Post and accompanied by original illustrations and beautiful cover images. Available to purchase in both print and digital editions.

For more information, visit shopthepost.com.

Do Americans Get Second Chances?

The Post can’t let September pass by without noting the birthday (September 24th) of one of its greatest contributors. F. Scott Fitzgerald published 69 of his short stories in our magazine between 1920 and 1937. He was the defining voice of the Jazz-Age generation—probably, as some have argued, because he invented it. Americans read his stories avidly, savoring their technical brilliance and looking for explanations for the brash, frantic young adults who were so unlike their parents.

He had an undeniable talent for storytelling, as well as skill in composing aphorisms. For example: “The test of a first-rate intelligence is the ability to hold two opposed ideas in mind at the same time and still retain the ability to function.”

But Fitzgerald’s work was rooted in doomed romance and thwarted ideals, which sometimes emerged in cynical expressions:

“I’m a romantic; a sentimental person thinks things will last, a romantic person hopes against hope that they won’t.”

“After all, life hasn’t much to offer except youth, and I suppose for older people, the love of youth in others.”

“Show me a hero and I’ll write you a tragedy.”

It was in this spirit that Fitzgerald wrote one of his most frequently quoted lines: “There are no second acts in American lives.”

It is a lone sentence, without context, found among the pages for a novel he never finished. Yet journalists often quote it when writing about failure. The phrase has been widely interpreted to mean that America gives no second chances. The value of the statement rests on its being written by Fitzgerald, who is presumably something of an authority on lost opportunities.

Did Fitzgerald Believe It?

Like many generalizations, it sounds more true than it, in fact, is. Generations of immigrants, for example, would argue the point. America was the great second act that spared millions of Europeans—the poor, unskilled, disadvantaged, and disgraced—from lives of obscurity and frustration.

Perhaps Fitzgerald meant Americans granted only one chance at success. If so, he was ignoring the comebacks of bankrupt author Mark Twain, failed Congressman Abraham Lincoln, and paralyzed ex-Assistant Navy Secretary Franklin Roosevelt. He was also disregarding the numerous new acts in the lives of Benjamin Franklin or Frederick Douglass.

Whatever faith Fitzgerald put into that sentence, it wasn’t shared by his contemporary, William Faulkner (born September 25, a year and a day after Fitzgerald). Faulkner was also a frequent contributor to the Post, which published 22 of his short stories between 1930 and 1967.

Faulkner was no romantic. In fact, he continually wrote of how romantic sentiments had crippled the South. His stories, which were almost all based in his native Mississippi, chronicled the South’s stubborn resistance to modern life and the damage done by hopes of resurrecting the past. His work earned him the Nobel Prize for literature in 1949.

He is perhaps less popular among American readers. His writing can be dense and convoluted. But he wrote about things that truly mattered, and were universal, not just Southern.

The Struggle That Lies Beyond Opportunity

In Faulkner’s Nobel acceptance speech, he looked far beyond second chances and missed opportunities, which limited a writer’s vision.

“The young man or woman writing today has forgotten the problems of the human heart in conflict with itself which alone can make good writing because only that is worth writing about, worth the agony and the sweat.

“[The writer] must learn them again. He must teach himself that the basest of all things is to be afraid; and, teaching himself that, forget it forever, leaving no room in his workshop for anything but the old verities and truths of the heart, the old universal truths lacking which any story is ephemeral and doomed—love and honor and pity and pride and compassion and sacrifice …

“I believe that man will not merely endure: He will prevail. He is immortal, not because he alone among creatures has an inexhaustible voice, but because he has a soul, a spirit capable of compassion and sacrifice and endurance. The poet’s, the writer’s, duty is to write about these things. It is his privilege to help man endure by lifting his heart, by reminding him of the courage and honor and hope and pride and compassion and pity and sacrifice which have been the glory of his past.”

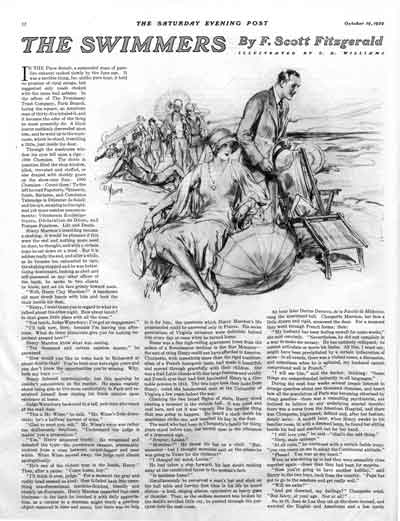

After these noble thoughts from Faulkner, we should let Fitzgerald make the case for second acts in American lives. He does so in his short story, “The Swimmers.” In its conclusion, he writes of an American sailing for Europe:

“Watching the fading city, the fading shore, from the desk of the Majestic, he had a sense of overwhelming gratitude and of gladness that America was there, that under the ugly debris of industry the rich land still pushed up, incorrigibly lavish and fertile, and that in the heart of the leaderless people the old generosities and devotions fought on, breaking out sometimes in fanaticism and excess, but indomitable and undefeated. There was a lost generation in the saddle at the moment, but it seemed to him that the men coming on, the men of the war, were better; and all his old feeling that America was a bizarre accident, a sort of historical sport, had gone forever. The best of America was the best of the world …

“France was a land, England was a people, but America, having about it still that quality of the idea, was harder to utter—it was the graves at Shiloh and the tired, drawn, nervous faces of its great men, and country boys dying in the Argonne for a phrase that was empty before their bodies withered. It was a willingness of the heart.”

FAULKNER (1897-1962)

“Thrift,” Sept. 6, 1930

“Red Leaves,” Oct. 25, 1930

“Lizards in Jamshyd’s Courtyard,” Feb. 27, 1932

“Turn About,” March 5, 1932

“A Mountain Victory,” Dec. 3, 1932

“A Bear Hunt,” Feb 10, 1934

“Ambuscade,” Sept. 29, 1934

“Retreat,” Oct. 13, 1934

“Raid,” Nov. 3, 1934

“The Unvanquished,” Nov. 14, 1936

“Vendee,” Dec. 5, 1936

“Hand Upon the Waters,” Nov. 4, 1939

“Tomorrow,” Nov. 23, 1940

“The Tall Man,” May 31, 1941

“Two Soldiers,” March 28, 1942

“The Bear,” May 9, 1942

“Shingles for the Lord,” Feb. 13, 1943

“Race at Morning,” March 5, 1955

“The Waifs,” May 4, 1957

“Hell Creek Crossing,” March 31, 1962

“Mr. Acarius,” Oct. 9, 1965

“The Wishing Tree,” April 8, 1967

FITZGERALD stories and articles (1896-1940)

“Head and Shoulders,” Feb. 21, 1920

“Myra Meets His Family,” March 20, 1920

“The Camel’s Back,” April 24, 1920

“Bernice Bobs Her Hair,” May 1, 1920

“The Ice Palace,” May 22, 1920

“The Offshore Pirate,” May 29, 1920

“The Popular Girl,” Feb 11, Feb. 18, 1922

“Gretchen’s Forty Winks,” March 15, 1924

“How to Live on $36,000 a Year,” April 5, 1924

“The Third Casket,” May 31, 1924

“The Unspeakable Egg,” July 12, 1924

“John Jackson’s Arcady,” July 26, 1924

“How to Live on Practically Nothing a Year,” Sept. 20, 1924

“Love in the Night,” March 14, 1925

“A Penny Spent,” Oct. 10, 1925

“Presumption,” Jan. 9, 1926

“The Adolescent Marriage,” March 6, 1926

“Jacob’s Ladder,” Aug. 20, 1927

“The Love Boat,” Oct. 8, 1927

“A Short Trip Home,” Dec. 17, 1927

“Bowl,” Jan. 21, 1928

“Magnetism,” March 3, 1928

“The Scandal Detectives,” April 28, 1928

“A Night of the Fair,” July 21, 1928

“The Freshest Boy,” July 28, 1928

“He Thinks He Is Wonderful,” Sept. 29, 1928

“The Captured Shadow,” Dec. 29, 1928

“The Perfect Life,” Jan. 5, 1929

“The Last of the Belles,” March 2, 1929

“Forging Ahead,” March 30, 1929

“Basil and Cleopatra,” April 27, 1929

“The Rough Crossing,” June 8, 1929

“Majesty,” July 13, 1929

“At Your Age,” Aug. 17, 1929

“The Swimmers,” Oct. 19, 1929

“Two Wrongs,” Jan. 18, 1930

“First Blood,” April 5, 1930

“A Millionaire’s Girl,” May 17, 1930

“A Nice Quiet Place,” May 31, 1930

“The Bridal Party,” Aug. 9, 1930

“A Woman With a Past,” Sept. 6, 1930

“Our Trip Abroad,” Oct. 11, 1930

“A Snobbish Story,” Nov. 29, 1930

“The Hotel Child,” Jan. 31, 1931

“Babylon Revisited,” Feb. 21, 1931

“Indecision,” May 16, 1931

“A New Leaf,” July 4, 1931

“Emotional Bankruptcy,” Aug. 15, 1931

“Between Three and Four,” Sept. 5, 1931

“A Change of Class,” Sept. 26, 1931

“A Freeze-Out,” Dec. 19, 1931

“Diagnosis,” Feb. 20, 1932

“Flight and Pursuit,” May 14, 1932

“Family in the Wind,” Jun 4, 1932

“The Rubber Check,” Aug 6, 1932

“What a Handsome Pair!” Aug 27, 1932

“One Interne,” Nov 5, 1932

“One Hundred False Starts,” March 4, 1933

“On Schedule,” March 18, 1933

“More than Just a House,” June 24, 1933

“I Got Shoes,” Sept. 23, 1933

“The Family Bus,” Nov. 4, 1933

“No Flowers,” July 21, 1934

“New Types,” Sept. 22, 1934

“Her Last Case,” Nov. 3, 1934

“Zone of Accident,” July 13, 1935

“Too Cute For Words,” April 18, 1936

“Inside the House,” June 13, 1936

“Trouble,” March 6, 1937