The Beauty and Pain of Old Photos

Many of us keep somewhere in our home a dust-covered carton crammed with decaying photographs that reveal the complex stories of our long-ago lives. The dread that attaches to these cartons — the reason they are seldom visited — is understandable. Experience tells us that the fading images stored within are bound to trigger good memories but, almost surely, some bad ones as well. They are fraught. I want to come back to them in a moment.

But first: Do you recall the Polaroid Corporation, maker of the instant cameras that were ubiquitous not so long ago? Polaroid went bankrupt in 2008. The internet and smartphones killed its business. Who needed pictures on disposable paper when you could endlessly manipulate your snaps on a hard drive or the web? Well, shock of shocks, Polaroid is back. Remarkably, it has lots of competition. Several well-known companies have joined the new Polaroid in selling inexpensive cameras that once again afford us the pleasure of taking poorly composed pictures that we can hold in our hands seconds later.

To touch a physical photo is, in some way, to be touched by it, instantly.

As it turns out — and this is wonderful, I think — the purity and imperfections of on-paper photographs retain a magic that’s not duplicable. There’s something ineffably satisfying about their tactile quality. Run your fingers across their surface! Don’t they feel timeless? To touch a physical photo is, in some way, to be touched by it, instantly.

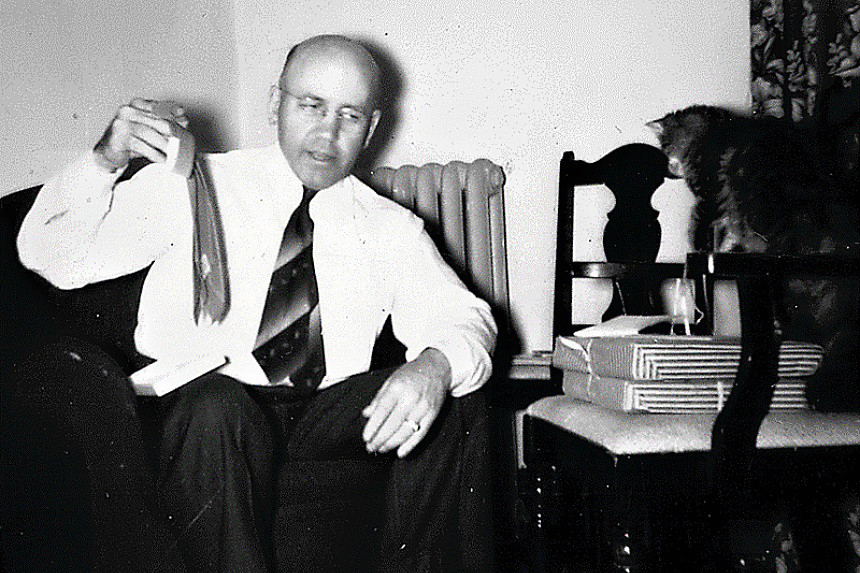

Which brings me back to the trove many of us warehouse in our homes. In my own case, that means the thousand or so crinkled photos that have survived multiple moves around the country. The pictures are unorganized and, most of them, uncaptioned. Recently, when I experienced an unaccustomed impulse to meditate on my life journey, I screwed up the courage to pry open the bin for the first time in many years.

Along with pictures of me in school, in the company of girlfriends, traveling, attending family celebrations, and so on — an array of stills documenting a not atypical lower-middle-class upbringing — I also found what I knew I would: Here were the painful visual reminders of too many tragedies.

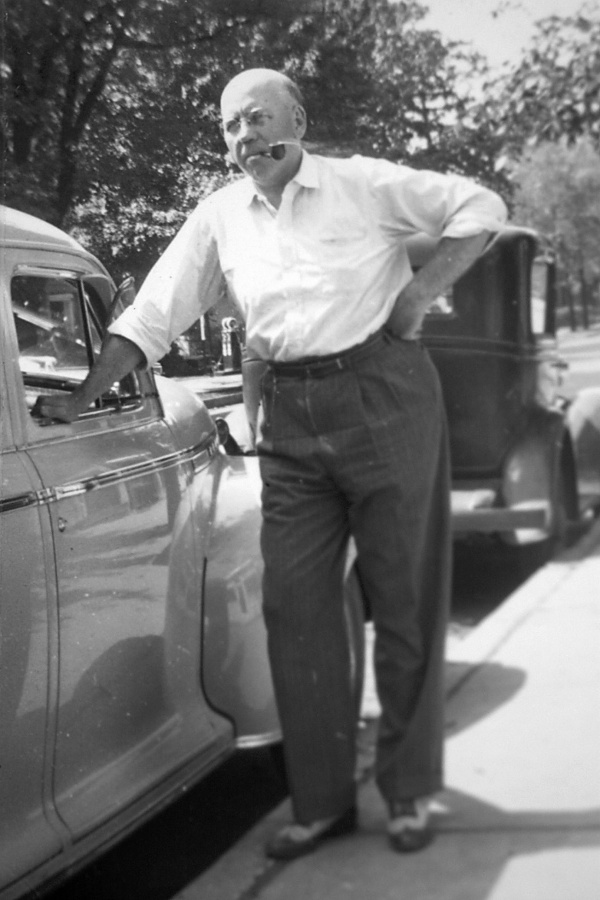

For a few hours I reviewed (and wept over) pictures of uncles murdered in the Holocaust, a favorite aunt who died young, a mother in the throes of a debilitating disease, an ex-wife who passed following a brief illness just this year. And then, haphazardly, I plucked from the pile a picture of my father, who had died unexpectedly during surgery. Somehow, I’d never seen that particular image before: “Pops” looking incredibly cool in his driving cap, at the steering wheel of a car on an unknown highway. Exactly as I remember him. It stole my breath.

Shimmering brightly on a modern flat screen, these pictures would have delivered far less wallop. However, to pinch them between my fingers, to hold them up to the lambent light of a late afternoon …

When at last I returned them all to their bin, two thoughts came into sharp focus. Photos of people we love are vastly more consequential than pictures of places and objects we love. And pictures on paper hit the heart harder than pictures displayed on glass screens. Now, more than ever, I believe these things to be manifest.

In the last issue, Cable Neuhaus wrote about the Slow Movement.

This article is featured in the November/December 2020 issue of The Saturday Evening Post. Subscribe to the magazine for more art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

Featured image: “It stole my breath.” This image of the author’s dad, “looking incredibly cool in his driving cap,” captured the man exactly as remembered. (Photo courtesy of Cable Neuhaus)

I Am the Tooth Fairy

“I know you’re the tooth fairy.” Noah, my 8-year-old, looks me dead in the eye. We are out to dinner. A large television hangs from the wall. Without blinking, he looks back up at the screen. A small, dry wing falls from my back and lands on the floor like a candy wrapper. The thing about not existing is that sometimes it’s a lot like being a mother.

“Sorry, Mama,” says Eli, my 6-year-old. He pats my hand and takes a bite of broccoli.

I think about all the elaborate notes in pink cursive, the 100 hundred shiny pennies in a cloth pouch, the blue stuffed cat, the five-dollar bill, the Superman, the glitter trails, the wooden hearts, the breath I held, the way I ever so gently lifted the pillow, the sparkle-stamped envelope with the tooth fairy’s address: 12345 Tooth Fairy Lane, Moutharctica, Earth. I kept myself secret. I tiptoed. I used my imagination, and now I’ve been caught. Noah looks at me again with a mix of sadness and pity and suspicion. I turn around to see what he’s watching. It’s a cartoon about a sea sponge who lives with his meowing pet snail.

A little light goes out inside me. But I can’t locate exactly what it ever lit up.

After Tinker Bell drinks the poison Hook left for Peter Pan, and her wings can barely carry her, and her light starts fading, and after she lets Peter Pan’s tears run over her finger, she realizes “she can get well again if children believed in fairies.” “Clap your hands; don’t let Tink die,” says Peter Pan. Many children clapped, some didn’t, “a few little beasts hissed.” Tink, of course, is saved. She flashes “more merry and impudent than ever.” It doesn’t even occur to her to thank the children who believed. Tink, whose name sounds like a penny tossed in a glass. Tink, whose name sounds like a wish that won’t come true.

Often as a mother I am in a cold sweat juggling whimsy and delight. “Magic anyone? Endless fun? Astounding joy?”

“No,” say my sons, “we’re good.” And they are. It’s me who isn’t good. It’s me who wants it. And I don’t even want it.

Often as a mother I am in a cold sweat juggling whimsy and delight. “Magic anyone? Endless fun? Astounding joy?”

What I want is my sons’ illegible, lyrical teeth. I want to turn them into an alphabet just for us. Letters with crowns and necks and roots. Milk letters. Deciduous letters. In this language I would draw a map that clearly marks where my sons’ wonder is buried so they always know where to go on their coldest days.

Clap your hands; don’t let mother die. My sons clap their hands and I brighten.

I’ve never seen a fairy. I’ve never looked up and seen a faint green glow. The closest I’ve ever come was once as a child — in a dream — I ran after myself, and when I caught up to me and turned around I wasn’t there.

We take shelter in children to escape oblivion. We ask the child to drag around the unwieldy weight of magic. To clap wildly. To believe in what we believe in no longer. We ask the child to keep the awe we forgot how to hold. The fairy isn’t the fairy. It’s the child who is the fairy. It’s the child who is enchanted, a metaphor, a shape-shifter. My sons keep bursting out of their skin. They smell like poppies, warm earth, milk. And then one day, out of nowhere, they won’t anymore. They are losing their baby teeth at what seems an alarming rate. Adult teeth bloom in their mouths. Their limbs grow longer and longer like shadows.

For whom is a child’s childhood? I think it’s for all of us. But it’s not for when we are children. Our childhoods are for later.

Some believe fairies are the discarded gods of the oldest faiths. Like shed skins of light. They continue to exist because they believe, like a child, that they exist.

The fairy isn’t the fairy. The mother is the fairy. The fairy flits back and forth, uncatchable. Who is she? The fairy is the space between knowing and not knowing. It’s the realization as it dawns. It’s what glows between a mother and her child. It’s Puck sweeping the dust with a broom behind the door. The fairy is the dust. The fairy is the door.

In 1691, Robert Kirk, a minister in the Church of Scotland, wrote a treatise claiming fairies were as real as you or me. It wasn’t published, though, until 1851, when “The Secret Commonwealth” was printed in a limited edition of a hundred copies. We each, he wrote, have a fairy counterpart, a co-walker, an echo. He described fairies as “somewhat of the nature of a condensed cloud and best seen in twilight.” Their bodies are spongeous and thin. “They are sometimes heard to bake bread.” “They speak but little and that by way of whistling — clear, not rough.” “They hang between the nature of God, and the nature of man.” Their body is “as a sigh is.”

They do not curse, but among their common faults are “Envy, Spite, Hypocrisy, lying, and dissimulatione.” They are prone to sadness because of their pendulous state. They can cure a sick cow. They steal milk, and when they are very angry they spoil it.

On May 14, 1692, Reverend Kirk took a walk in his nightgown on the fairy hill beside the manse. Later that evening, on the same hill, his body was found dead. The body that was buried, according to locals, was a changeling. The fairies had kidnapped the minister in his nightgown, replaced him with a dead fairy, and held the reverend captive in Fairyland.

The punishment, it seems, for believing too much in fairies is to be snatched away by them for eternity.

Three days after I give birth to Noah, I am nursing him in a soft, beige rocking chair when a goat walks in. “Hello,” I say. The goat, being a goat, says nothing. Most likely, I am hallucinating from no sleep. Most likely, a little piece of this world has torn and through the rip a goat has walked in. The goat lays his soft head on Noah’s head, like a kiss. The room fills up with wildflowers and then empties of wildflowers and then the goat is gone. Who am I to say there is no thin veil between this world and fairyland? I know this now, but I didn’t know it then: I am the tooth fairy.

This is how you can tell if your baby has been replaced by a changeling: boil water in an eggshell. If your baby is a changeling it will laugh and reveal it’s as old as the forest. In all its years, it will say when it suddenly begins to speak, it has never seen anyone boil water in an eggshell. If you wish to keep the fairies away, put the Bible, a piece of bread, or iron in your child’s bed. And if you wish to see a fairy, take the rope that once bound a corpse to a bier and tie it around your waist. Bend over and look between your legs. A procession of fairies will appear. If the wind changes directions while you do this, it is possible you will drop down dead.

There are two kinds of fairies. There are the “trooping” fairies, who live together on a hill. And then there are the ones who attach themselves to individuals, like a haunt. If I were a fairy, I’m certain I’d be the second kind, but to tell you the truth I’d make a terrible fairy. A terrible mother fairy who writes about fairies, and by doing so angers them all.

We are at the pediatric dentist because Eli has flown off his scooter and landed on his face. The dentist, who looks more like a very old child dressed up as a dentist than an actual dentist, puts Eli in a chair and raises it with a crank to the ceiling. She climbs up a ladder and examines him in the air. “You okay?” I call out from down here. From all the way down here. She tells me his two front teeth will have to be pulled. “Bad news,” she says, smiling. She lowers Eli and climbs back down. She hands me a brochure on sedation options. She is wearing tiny pink sneakers. I imagine a back room filled with sparkling white teeth. Nightly she grinds them. And stirs the powder into her warm milk. Unlike the rest of us, she will live forever.

“Can we err on the side of nature?” I ask. “I don’t recommend that,” says the dentist who clearly was once a fairy.

She shows me two fake front baby teeth attached to a wire. After she pulls Eli’s teeth she can “cement the device into his mouth,” she says. “I made one for my daughter,” she says, her red cheeks glowing.

The dentist’s office is decorated like an amusement park: vending machines filled with toys, televisions frantic with cartoons, posters of wide-eyed animals in pants. The instruments on the dentist’s tray — forceps, mouth mirror, periodontal probe — shine as the only reminder of where we are. There is even a giant stuffed panda. All you need to do is leave your name and number on a small piece of paper for the chance to win. I am so distraught I almost enter. Would she deliver the panda herself? Would she knock on our door with the prize and then devour us?

“Let’s get out of here,” I say to Eli. “Let’s run, Mama,” says Eli. And we run. We run home where it’s safe. Eli’s baby teeth stay in for another year. And when they fall out naturally I add them to the rest. Between Noah and Eli I have twelve. Twelve teeth. Sometimes I just hold them. Noah’s in one hand. Eli’s in the other. Proof of their babyhood. Proof of the mouths they left behind. Those baby mouths that spoke words thickly accented by the land they came from. Maybe it’s those teeth that are the fairies. The ones the children, in order to grow, must cast off. The teeth that made little holes in the air with new breath.

If I were really the tooth fairy, I’d lay each tooth, like a body, on a rose leaf. I’d carry them one by one over my head through the streets. The air would brighten, and grow sad and sweet. And I would sing, though I cannot sing, a lament for everything I must remember and everything my sons must forget.

Last night I slept with all my sons’ teeth underneath my pillow. And when I woke up, Noah and Eli were leaving me notes. They each had a long white beard, and they were very old and wise and radiant. I had caught them. And then I woke up again.

First published in The Paris Review Daily.

This article is featured in the November/December 2020 issue of The Saturday Evening Post. Subscribe to the magazine for more art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

Featured image: Take the Fair Face of Woman, and Gently Suspending, with Butterflies, Flowers, and Jewels Attending, thus Your Fairy is Made of Most Beautiful Things by Sophie Gengembre Anderson (1869)

Horror for the Whole Family: Halloween Books for All Ages

Halloween is upon us once again. Last year, the Post looked at the question, “What’s the right horror film for the whole family?” And while staying in for movies is still an excellent choice for this spooky season, especially with the pandemic still present, films aren’t your only choice for eerie entertainment. So the new question becomes, “What are the right horror reads for the whole family?”

Every family’s view of content is different, and every family has a different standard for when it’s okay for the kids to indulge in scary fare. What we have here are some baseline recommendations, standout books that you might check out as starters, along with some appropriate ages. Again, your own idea of what’s appropriate and when may vary, but that’s why comment sections were created.

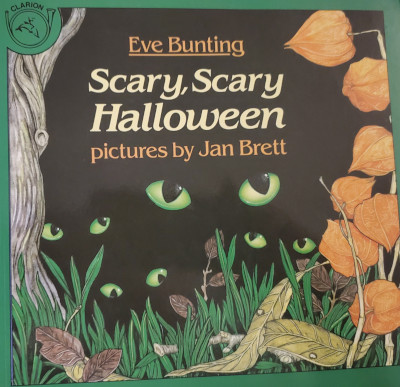

1.The Littles (9 and under): Scary, Scary Halloween by Eve Bunting and Jan Brett (1988)

Halloween-themed picture books abound, with lots of great, funny reads like Goblin Walk, but this one is a superlative effort from two huge talents. Eve Bunting has more than 250 books to her credit; she moves as easily from fiction to non-fiction as she does from picture books to novels. Jan Brett has been writing and drawing books for kids since the 1970s, and she’s received effusive praise for her lovely, intricate art. Scary, Scary Halloween brings them together in a delightful way, with rhyming verse and outstanding visual renditions of a scary Halloween night. An unseen narrator talks of monsters stalking through the neighborhood before the story takes not one, but two, surprise twists. It’s a great one to read to the little ones, and to have them read back to you as they get bigger.

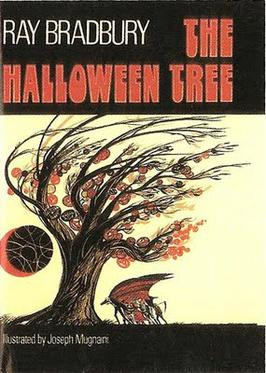

2. Kids to Tweens: The Halloween Tree by Ray Bradbury (1972)

Let’s be clear: Ray Bradbury’s The Halloween Tree is for EVERYONE, but it serves this particular demographic extremely well. Bradbury is, of course, one of the most exalted names in science fiction and fantasy, but he might also be the King of Halloween. His loving and nuanced takes on the holiday cause his name to appear repeatedly (and deservedly) on this list. The Halloween Tree is a touching story about friendship that also delves into the history of the holiday and its antecedent, Samhain. After a boy named Pipkin disappears, eight of his friends come together with the strange Mr. Moundshroud to travel through time to find their friend; along the way, they learn about the traditions of the Greeks, Romans, and Celts, visit medieval France, and witness what happens at Mexico’s Day of the Dead celebration. When the cost of saving Pipkin becomes clear, his friends come together for their friend in a moving finale.

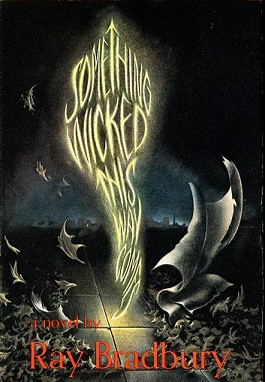

3. Teens: Something Wicked This Way Comes by Ray Bradbury (1962)

Today’s teens have access to a steady diet of horror material in both print and film; between libraries and streaming services, there’s not a lot that they haven’t already seen. That’s what makes Something Wicked This Way Comes special, in a way, because they might not have seen it. Bradbury’s 1962 masterpiece is all about the transition from youth to adulthood, while also baking in the regrets of age. When a strange carnival arrives in Green Town, Illinois on October 23, 13-year-old best friends Will Halloway (born one minute before midnight on October 30) and Jim Nightshade (born one minute after on October 31) are drawn into its orbit. At first, only Will and Jim seem aware of the unnatural events unfolding from the Cooger & Dark’s Pandemonium Shadow Show, but they find an unexpected ally in Will’s 54-year-old father. You can smell the autumn air in Bradbury’s rich descriptions of the season. The story, by turns wistful and terrifying, is one of the gold standards of dark fantasy. Teens can easily identify with the protagonists, as one of the primary forces in their own lives is the pull of adulthood.

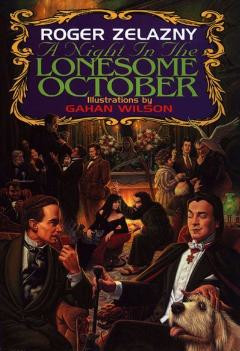

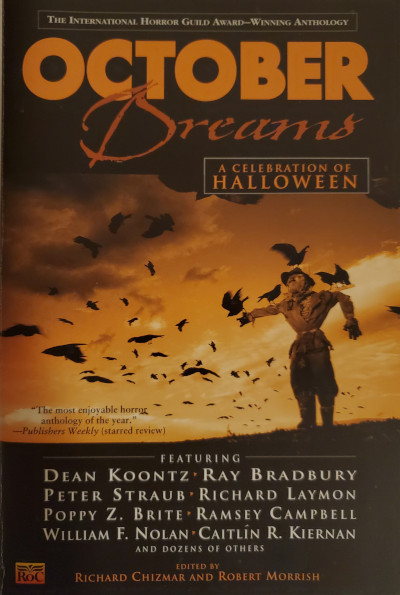

4. Adults: A Night in the Lonesome October by Roger Zelazney (1993) and October Dreams: A Celebration of Halloween (edited by Richard Chizmar and Robert Morrish, 2000)

A Night in the Lonesome October (not to be confused with Night in the Lonesome October by Richard Laymon, which is great in its own right) is creepy, funny, delightful, and demented. Zelazney was the celebrated writer of the bestselling The Chronicles of Amber series and dozens of other works; he won the Hugo Award six times and the Nebula three. 1993’s ANITLO was one his favorites of his own work; it was also his last novel, as he died in 1995. But what a great final statement it is. After an introduction, the 31 remaining chapters each take place on one day in October leading to Halloween in late 1800s London. The story is told from the point of view of Snuff, the canine companion and magical familiar of one Jack the Ripper. However, Jack is actually trying to save the world in a story that involves (either directly or by clever parody) the Lovecraft mythos, Dracula, Sherlock Holmes, the Wolf Man, the Frankenstein Monster, Rasputin, and more. The book is by turns haunting and hilarious, with Snuff and the other familiars alternately trying to help their masters save or destroy the world. Surprise alliances and betrayals abound, and it’s a real feat of imagination.

On the darker side, the 2000 anthology October Dreams: A Celebration of Halloween is simply one of the best collections about Halloween ever put to print. Collecting short stories along with non-fiction Halloween reminiscences by a murderer’s row of talent, the book includes the likes of Bradbury, Dean Koontz, Poppy Z. Brite, Christopher Golden, Jack Ketchum, Gahan Wilson, Richard Laymon, Dennis Etchison, Ramsey Campbell, Peter Straub, and many more. At over 650 pages, it’s a slab of fiendish goodness.

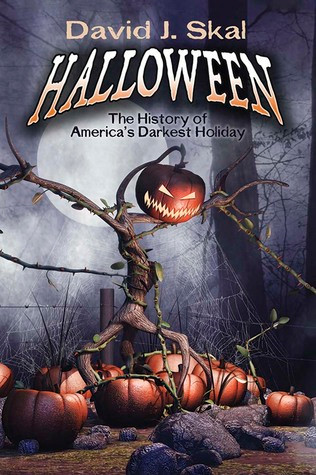

5. The Adult History Buff: Halloween: The History of America’s Darkest Holiday by David J. Skal (2016)

An October surprise bonus category! Yes, The Halloween Tree digs into the roots of the holiday, but this is a phenomenal book by one of the most authoritative writers on horror. Skal has written essential non-fiction like The Monster Show: A Cultural History of Horror, Hollywood Gothic, and Something in the Blood: The Untold Story of Bram Stoker, the Man Who Wrote Dracula. Here, he turns his keen insights to Halloween itself. Skal’s real talent lies in engaging a topic on both the macro and micro level, juxtaposing how that topic impacts the culture as a whole while also using laser-precise examples to show just how deeply that impact runs. Skal’s examination runs the gamut from the early Celtic days to a present where we (in non-pandemic years) spend about $9 billion celebrating the holiday.

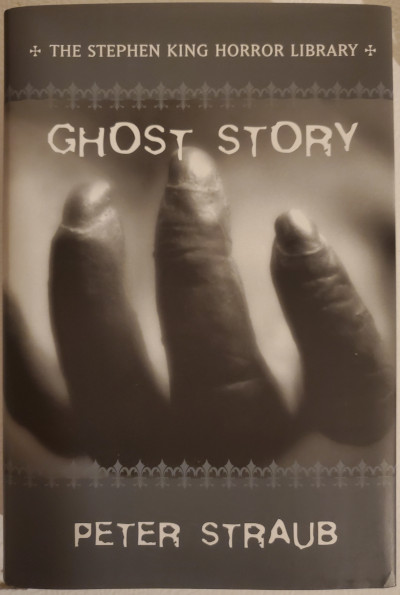

6. Grandparents: Ghost Story by Peter Straub (1979)

This one goes off theme just a tiny bit, but bear with it. Yes, Ghost Story takes place across multiple time periods with one of the most climactic sequences occurring during a blizzard. But it is one of the grand champions of scary storytelling, and the initial protagonists are a group of older gentlemen and one gentleman’s wife. With many mature main characters and Straub’s deep appreciation for the canon and history of American horror (references to Nathaniel Hawthorne and Donald Wandrei abound, and nods are clearly made to George Romero and Straub’s pal Stephen King), Straub crafts a particularly literary story that thrives on human emotion. There is some really dark stuff, but there are also seeds of hope, especially when the older men reach out to two other protagonists (one much younger) to help them navigate the terror that has them under siege.

And there you have it: like the film list, it’s a list to get you started (and to start discussions). Enjoy this very strange season, get lost in the books that you intend to read, and maybe, just maybe, leave a light on.

Featured image: Marsan / Shutterstock

The Last Supper

In my family we call it “pulling a Haubner:” enjoying one meal while discussing what/when/where we’re going to eat next.

We often started planning the day’s eating adventures at breakfast, our thinking processes juiced up by Bloody Marys. My sister and I loved breakfast out. I would feel guilty having a vodka drink at home at eleven in the morning, but call it brunch and bring on the booze.

The waitress would put our plates down and forks would fly as mom, sis, and I immediately began digging in to each other’s omelet, breakfast burrito, and ricotta pancakes and congratulating ourselves on our astute ordering: we had nailed another trifecta.

Our ideal restaurant seating would have been a big Lazy Susan that we’d keep spinning: food roulette. We always shared. There was no worse sin in our family than two people at the table ordering the same meal. If I see a couple in a restaurant with identical plates in front of them I get gooseflesh: it feels like someone is walking over my mom’s grave.

But this was before mom had her dirt sandwich. She reclaimed her pancakes and asked, “Should I defrost a chicken for dinner?”

My sister and I shot each other looks, mouths too full of cheese and egg to talk. Mom’s freezer was an infamous icy graveyard. Once searching for ice cream that wasn’t completely crystalized, I unearthed a brown paper and string packet encased in frost: it was ancient venison, shot by her second husband who had been dead for a decade. On a visit home from college, my mom poisoned me with frozen crab dip; when I checked the expiration date it was written in cuneiform.

We passed jam and hot sauce and got coffee refills while mom switched to debating the merits of her favorite barbeque restaurant vs. “That place I took you last time for chili rellenos, and there’s the good bakery across the street with the tres leches cake.”

A chili relleno is basically fried cheese loosely tethered to a green pepper and tres leches is cake drowned in whipped cream and sweetened condensed milk. I had been trying to keep my annual trip home down to 2,500 calories a day. I said, “What about that new deli you wanted to try? We could split sandwiches.”

“You guys are pulling a Haubner,” said my sister, and then unable to resist, offered her own suggestion: dining on chicken wings and nachos at the bar of her favorite dive.

Food, for tight-ass Norwegians like us, had become how we expressed love: try that, taste this, look what I made for you. (I tried not to take it personally that my mother could never remember I hated her famous sticky-sweet, tooth-cracking English toffee. On every return home she greeted me with a fresh batch.)

It’s a mystery when or how my family developed our food fixation. Growing up I was that enfant terrible, the picky eater. Eating was a chore I had to do three times a day, like washing the dishes. The smell of eggs, cheese, and fish, particularly the classic school lunch tuna noodle casserole, felt like a WWI gas attack, rendering me hot, clammy, and pukey. I barely made it through Fridays in grade school.

That still left plenty of stolid Midwest food I grudgingly consented to eat, a rotation of steaks, chops, and chicken, all with minimal seasoning. Minnesota hot dish was also acceptable, as long as it didn’t have any weird ingredients, like herbs or spices.

I didn’t see a garlic bulb till I was 20. In 1960s Duluth, garlic came in a salt. Mom bought some, stashed it next to the mysterious Accent, and when she remembered, sprinkled it on spaghetti before serving. The only fresh herb I knew was parsley, something you put on a plate and then threw away.

Family dinners were a vegetable, meat or chicken, rice or potatoes, and mostly devoid of conversation once we had exhausted what happened in school that day. I ate as little and as fast as possible so I could go stimulate my mind with The Beverly Hillbillies or The Munsters, the original Must See TV.

Maybe I am older than Clarence Birdseye, but the vegetables of yesteryear were fresh and seasonal. I violently rejected most of them anyway, causing such awful dinner time scenes that you would think I’d break out in PTSD at the sight of a Brussels sprout.

In the spring we’d eat fresh green peas (my Grandma Haubner, the family gourmet, fancied her peas up with canned pearl onions; Grandma Spellman, the earth mother, grew her own). In the summer we gnawed on cobs of sweet corn so bathed in Land O’Lakes butter that even the little plastic holders stabbed into the sides were slippery. In the fall enormous squashes, the colors of the turning leaves, were baked with brown sugar and cinnamon. I still wouldn’t eat them.

In the winter, vegetables came in cans, with most of the texture and taste removed. I did have an odd fondness for Del Monte canned zucchini, stewed in a thin bland tomato sauce to a consistency one step above baby food.

Going to a restaurant for dinner was an adult activity. Once a week, my parents got spiffed up — mom in Cherries in the Snow lipstick and a towering beehive fresh from the salon, dad in a dark suit, narrow tie, and a splash of Old Spice. We were left with a baby-sitter, Swanson TV dinners, and Saturday Night at the Movies while our parents headed out to meet friends and have highballs and eat a meal that was not disrupted by a child throwing up broccoli.

For us kids, eating out meant eating in my mom’s car. When my dad skipped family dinner in favor of a Brotherhood of Elks piss-up, my mom hung up her apron and oven mitts and drove us girls to The London Inn for french fries and hamburgers. I always ordered mine CATCHUP ONLY; but sometimes the rocket scientists manning the grill slipped up. I had learned to remove the top bun and carefully examine my burger before taking a bite. An errant pickle was peeled off and tossed out the window; but if I discovered even a dab of mustard the whole shebang was rejected outright, forcing my disgusted mom not only to eat two hamburgers (child of the depression, she never, ever wasted food) but also to shell out another 39 cents.

O happy day when my mom pulled her big green Chrysler up in front of Bridgeman’s and gave us each a dime for ice cream cones. The concept, known in Italy since the Renaissance that you could indulge in two flavors of ice cream, was utterly foreign to the Upper Midwest’s Lutheran sensibilities. It took me longer to pick a flavor than it did to eat the ice cream cone. Perennial contenders were rocky road, because you got chocolate, marshmallow, AND nuts; butter pecan, salty and sweet; only-in-August peach ice cream, frozen summer on my tongue; and mint chocolate chip (which I still adore, although my older son says I might as well go in the bathroom and eat toothpaste).

Pizza, which kept my own children from starving, was unknown to my family, even though Duluth is the proud home of Jeno’s Pizza Rolls, famous for always being served at a temperature rivaling the melting point of steel.

Then Shakey’s Pizza Parlor opened up in the Arrowhead Mall.

Shakey’s Pizza was a mutt of a place and I loved it: supposedly Italian food that you could get Hawaiian-style, with sticky pineapple rings and cubes of pink canned ham (yes, those were the Dark Ages), eaten in an unconvincing replica of an Old West saloon, complete with swinging half doors and a player piano tinkling out “Bicycle Built for Two.” Shakey’s biggest appeal was that Orange Crush and root beer and Coca-Cola came in giant glass pitchers: pop was verboten in my dental-conscious home. My sister and I often came to blows over the last inch of Dad’s left in the pitcher.

All my most memorable childhood meals involved something awful happening. There was the dinner in Tijuana (dental convention) where after half an hour of crooning along to “Cielito Lindo” and “La Paloma” my dad stiffed the mariachi players who then strong-armed him as we left the restaurant, relieving him of all his pesos. The Chinese meal in San Francisco (dental convention) that ended in shouting and tears over us kids being denied a two-buck bag of fortune cookies. (“You’re not even going to eat the cookies!”) And who can forget the Christmas dinner where, like dominoes, one grandkid after another spilled their milk. Grandpa Haubner, already at half-mast, pulled himself upright and yelled, “The next damn kid who spills their damn milk…” accentuating each word with a fist bang on the table until his own glass, filled to the rim with ice cubes and Wild Turkey, tipped over, sending grandpa over the edge and all us kids under the table to hide.

It wasn’t till I went away to school in Minneapolis that I discovered that meals eaten in company can be a source of pleasure and comfort, nourishing stomach and soul. The first weeks of college I was wide-eyed-wowed by my dorm’s cafeteria: two choices for dinner! A salad bar featuring pale iceberg lettuce, slices of unripe tomatoes, shredded carrot mixed with raisins, and macaroni doused in mayonnaise! Best of all, there was a glorious stainless-steel self-serve dispenser of chocolate and vanilla soft ice cream. I served myself a lot of that.

But it didn’t take long for me, my roommate, and two new girlfriends to grow weary of baked chicken, square fish, and greyish beef; even the soft serve lost its glow. A few blocks from our dorm was the famous Mama Rosa’s, a red sauce emporium that used real garlic and other exotic ingredients, like oregano; if the wind blew east towards the Mississippi, it was as if cartoon scent waves of simmering sauce wafted us out of the dorm down to the restaurant.

Mama Rosa’s food was a revelation, as spaghetti in my house was a can of Hunt’s Tomato Sauce mixed with browned hamburger, dumped over flaccid noodles, dusted with what claimed to be Parmesan cheese but more closely resembled sawdust, and occasionally garlic salt.

My freshman year all I had for mad money was what I had saved from my summer waitressing job, so Mama Rosa’s was a big splurge. Three dollars and ninety-nine cents got me a steaming Mount Etna of baked ziti, oozing with melty cheese, and if I went and hid in the ladies’ (since I looked like I was twelve), my friends could usually order a round of fifty cent glasses of vinegary red wine without getting carded.

That four-way friendship was founded over red and white checked tablecloths, eating and drinking and swapping tales of virginity lost to boyfriends current or ex, drunken escapades we miraculously managed to survive, of warding off handsy male high school (in my case, junior high) teachers. A second glass of wine found us revealing glimpses of family skeletons and confessing secret dreams and goals and sorrows, conversations that would have been impossible in our dorm’s florescent-bulbed cafeteria.

Reluctant to go back to barely cracked textbooks and indecipherable lab notes, we lingered over the crimson dregs in our glasses until Mama herself came and slammed the bill on our table. Stuffed and tipsy and reveling in the bliss of a friendship that was brand new but felt eternal, the four of us waddled down the cold dark street back to our dorm.

Also close to my freshman dorm was a mediocre hamburger joint, Embers. A fellow impoverished student, the first guy who ever asked me out to dinner (my high school boyfriend and I just got high and had sex), took me there. He looked at the menu, then at me, and said, “I’ll just have the grilled cheese. What would you just have?”

I get it. During my own lean years I let any guy who asked buy me a steak, most of which came home in a doggie bag to be portioned up as that week’s dinners. I was so broke I was often tempted to ask, “If I don’t order the shrimp cocktail can I have the $12.95?”

Besides providing meals for the week, a restaurant date was a great way to decide who I’d never go out with again. The man who wouldn’t give me a taste of his fettuccine alfredo? My mother taught me to not trust people who don’t share their food. Then there was the guy who drowned his side salad in bright orange French dressing. And you think you’re going to kiss me with that mouth?

Some guys passed the cut. Twice I fell in love over restaurant dinners. The first time I was courted with Chateau Lafite Rothschild and steak Diane. (If you want to start a flame in my heart, just bring me a plate of food, souse it with brandy, and light a match.) The second time I was treated to cheap fiery vindaloo and giant bottles of Kingfisher beer. As my spiritual teacher Marilyn said in Gentlemen Prefer Blondes: “It’s just as easy to fall in love with a rich man as a poor one.”

When and if the magical world of restaurants comes back, what will be the new rules? Will lovers be social pariahs if they swap spit between courses, risking more than a broken heart? Can I stick my fork in my dining partner’s plate without feeling like Typhoid Mary? Was the guy hording his fettuccine right?

While preparing home-cooked meal Number 224 (probably chicken), I tumble into restaurant memories. My mind doesn’t turn to my one and only dinners at La Coupole in Paris, The Four Seasons in New York, or the Pump Room in Chicago. I don’t long for those big birthday meals, with cake and too many candles and singing waiters. I reach back to recall the most ordinary of meals with friends when we had nothing to celebrate but each other.

I would pay a lot more than $3.99 to have one more baked ziti dinner with my three old college pals, to see their big smiles revealing teeth stained with cheap wine, their pretty eyes catching the glow of a candle stuck in a Chianti bottle.

I’d also pay beaucoup bucks to sit down to dinner with my best friend of forty years, a former restaurant critic who commandeers the ordering so we always eat very, very well. Tables for two are our copy desks for breaking news of marriages made and broken, children (hopefully one day all four of our kids will be happy at the same time), job hirings and firings, moves out of state and to foreign lands. The two of us have developed the ability to swap news by talking and listening simultaneously: it saves time so we can get down to the serious work of drinking and making each other laugh.

Yeah, given the choice, I’d take a well-lubricated restaurant meal with good friends over a romantic dinner for two.

I’m terrified that a dinner out, with family or friends or a new love, has been relegated to quaint nostalgia, like a taffy pull or box social. “Hey kids, did I ever tell you about how grampa and I used to eat at places called restaurants where strangers cooked and brought you food?”

A whole religion is based on dining out. What is Christianity but communion, a recreation of the Last Supper, a meal obviously eaten in a restaurant. You can’t tell me that St. Peter was topping up everyone’s glass while Judas checked to see if the roast lamb was done. Nope. There were handmaidens waiting on tables who missed out being in the Leonardo painting; a former serving wench myself, I bet they were huddled in the courtyard, smoking, counting up drachmas, and debating which Apostle was the cutest.

The place the Last Supper occurred, The Room, even sounds like a restaurant. And Jesus passed around the bread and wine, giving us a new commandment: “Thou shalt share thy grub.”

My own Last Supper was this past winter, in a lovely restaurant in a strip mall in Scottsdale, eaten with one of those old college buddies and her late-in-life soulmate; she was wearing the goofy, dumbstruck look of love I hadn’t seen since we were young and all things were bright and beautiful. I had lamb ragù, my pal had quail, and her charming husband (who picked up the bill, I like that in a man), had the fish. And yes, we shared everything.

Featured image: Endless Buta / Shutterstock

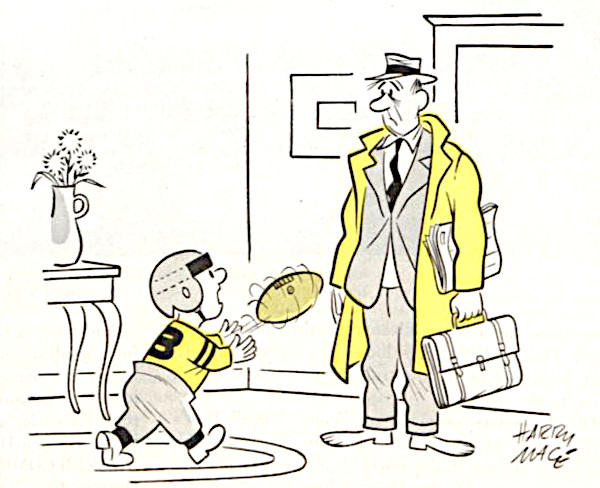

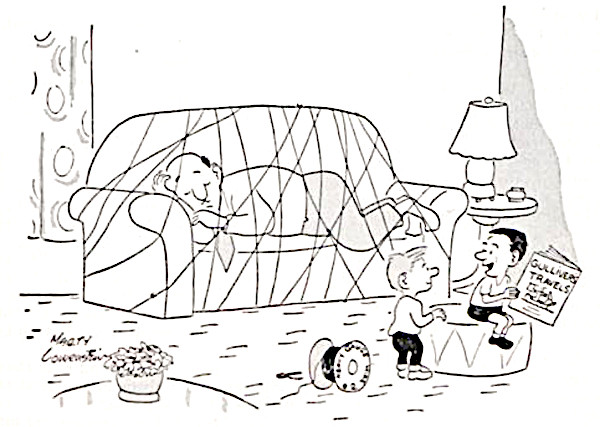

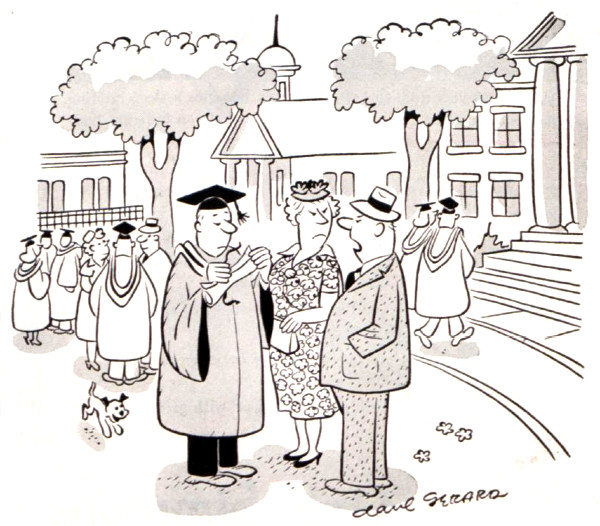

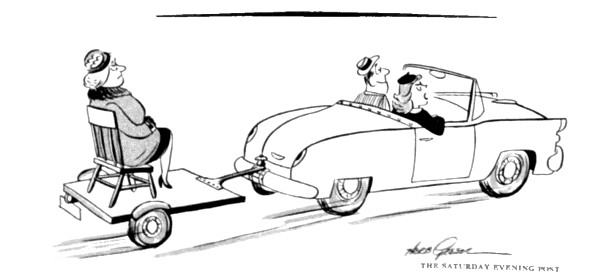

Cartoons: Dear Old Dad

Want even more laughs? Subscribe to the magazine for cartoons, art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

Goldstein

November 17, 1951

Harry Mace

November 15, 1952

Stan Hunt

September 13, 1952

Marty Lowenstein

August 4, 1951

Dave Gerard

June 2, 1951

Hank Ketcham

May 26, 1951

O’Brien

April 10, 1954

Larry Harris

February 2, 1952

Harry Mace

December 15, 1951

Want even more laughs? Subscribe to the magazine for cartoons, art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

What Our Dads Did for Us

Each year when Father’s Day rolls around, I think of the late Erma Bombeck.

While she mined family life for years in her syndicated column and best-selling books, on June 21, 1981 — Father’s Day that year — she plumbed memories of her father for one of the most unforgettable columns ever to appear on the printed page.

If you think that’s a bit much, it was so good it was reprinted by Reader’s Digest. And in 1989, when the editor of Reader’s Digest undertook a special project to determine the best articles that had ever been published in the magazine — he went back and read through all 67 years of issues — Erma Bombeck’s Father’s Day column was one of them.

If you wonder why, consider her opening.

When I was a little kid, a father was like the light in the refrigerator. Every house had one, but no one really knew what either of them did once the door was shut.

For years I used Erma Bombeck’s Father’s Day column as an example of the power of the telling detail when I taught feature writing at the School of Journalism and Mass Communication at the University of North Carolina (now the UNC Hussman School of Journalism and Media).

He opened the jar of pickles when no one else at home could.

He was the only one in the house who wasn’t afraid to go into the basement by himself.

A bit later —

It was understood that whenever it rained, he got the car and brought it around to the door.

When anyone was sick, he went out to get the prescription filled.

And —

He took a lot of pictures, but was never in them.

When we discussed it in class, students — year after year after year — would say, “My father didn’t do that. He cut the wood for the fireplace.” Or, “My Dad didn’t do that. He put up a backboard and hoop on the garage so I could shoot basketballs.” Or, “Daddy didn’t do any of those things. But when he made the popcorn, he put lots of butter on it.”

That is what fathers do.

That with time we come to appreciate, and recognize on Father’s Day.

While it’s been celebrated by Catholic institutions since the Middle Ages (March 19, St. Joseph’s Day), and President Woodrow Wilson tried to establish a national Father’s Day in 1913, it wasn’t until the 1930s that the idea gained traction, due in part to growing support from manufacturers and merchants who would benefit from the sale of items for fathers.

Still, many Americans continued to resist, viewing Father’s Day as nothing more than an attempt to replicate Mother’s Day. (I remember asking when Children’s Day was and being told, “Every day is Children’s Day.”)

The resistance would weaken with the years, but it was not until 1966 that the first presidential proclamation designating the third Sunday in June as Father’s Day was signed — by President Lyndon B. Johnson. In 1972 President Richard Nixon signed the law making it a permanent national holiday.

With my first Father’s Day gifts, I learned — with a little help from Christmas — never to buy my father ties. I might be young and still growing, but I picked up quickly on the fact that, however nice he was, however much he loved me, he’d rather pick out his own.

Like Erma Bombeck, it’s when I look back that I realize how much he did.

My father was the one who set and emptied the mouse traps. He stood alongside the Christmas tree in the lot, turning it slowly as my mother and I stood back, checking the symmetry, to be sure it was perfect. He spent his summer vacations painting the kitchen (or bedroom or bathroom), undoubtedly happy to get back to work.

He wasn’t a gourmet cook, or even your everyday cook, but on Sunday morning he went into the kitchen and made pancakes. He would let the batter spread out on the griddle into a near-perfect circle, then add a bit at the top of one — mine — like the stem on an apple. A “handle,” he said. Just for me.

As most fathers do, I suspect, he deferred to my mother on most of the things a parent can rule/guide/steer/suggest — especially, mothers with girls. But he insisted on two things.

1. I must know how to reconcile a bank statement. I do. But I don’t like to do it.

I like to think he would be as happy as I am that technology, i.e., my online bank account, has eased that almost into oblivion.

2. I must put my own worms on the fish hook. I did. But I’d never enter a fishing contest, however shiny the first prize trophy.

Did I mention he cleaned the fish?

My father did not run alongside my bike “for at least a thousand miles until I got the hang of it,” as Erma Bombeck’s father had, but we faced the same challenges of forward motion when he taught me how to drive. The most vivid and lasting memory that came out of that was my appreciation — and his, I daresay — for the invention of the automatic transmission, which would bear many names, the one I remember being Hydramatic.

I consider it up there with the discovery of fire and invention of the wheel.

Alas, it was still in the laboratory the afternoon Daddy took me out to a gravel country road, more specifically a hill with a considerable incline, and introduced me to the finer points of coordinating the clutch, the accelerator, and the brake.

It is an acquired skill.

Bob Newhart had a classic comedy routine on this trying form of human endeavor known as driver education that I heard on the radio one afternoon while driving on the Merritt Parkway in Westport, Conn., and laughed so hard I almost had to pull over. In that case, it was a paid instructor suffering the torment of a driver still in training.

My father did it for love.

And I love him for it.

And all the other things he did that time has turned to gold.

Little things.

Things that have survived the years, the day’s breaking news, the aches and pains of aging, to not only mean a lot. To mean everything.

Like the time — it was before Hallmark cards became the staple of Valentine’s Day — that I worked on a package of pieces for Valentines that you assembled yourself. My grandmother had bought the package for me, and this particular afternoon I was at her house working on the Valentines to present to my loved ones.

You had to paste the lace-y white sheets over the Valentines. They had little paper feet you attached appropriately. Although the paste that I used was homemade — flour and water in the proper proportions, which my grandmother knew — it worked on the little paper feet. They stuck nicely.

And that might have been the end of it except that when I finished I decided to make chocolate pudding for dessert that night. I was only seven, but I managed to reach the cookbook. I mixed the ingredients, found a pan into which I poured the pudding-to-be, and set the pan on the stove. A white enamel stove set up on cabriolet legs, the burners were chest high for me. The handles were on the front, though, so I could reach them. They were also white ceramic, and I turned the one in front of me. It was a gas stove, with flames that licked at the sauce pan.

I stirred. And stirred. And stirred.

When it didn’t thicken, I remembered the flour and water my grandmother had mixed for the paste for my Valentines. And creating a family story for years to come, put the paste in the pudding.

By the time we went to eat it, the pudding still looked like the chocolate pudding I had poured into the pretty glass dessert dishes. But it had taken on certain qualities and characteristics we associate with concrete. I couldn’t get my spoon into it, nor could most of the adults at the table. But Daddy chipped away … and chipped away … and chipped away until he had a spoonful. You could almost hear it clink as it went down.

He even managed a smile as he looked over at me and said, “It’s very good, honey.”

All photographs courtesy of Val Lauder

Cartoons: Mother-in-Law

Want even more laughs? Subscribe to the magazine for cartoons, art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

Peter Wyma

November 20, 1954

October 27, 1956

George Wolfe

October 16, 1954

Edwin Lepper

August 14, 1954

Gustav Lundberg

March 17, 1951

Dick Cavalli

March 1, 1952

Chon Day

February 23, 1952

Want even more laughs? Subscribe to the magazine for cartoons, art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

When Someone You Love Is Behind Bars

For many Americans, the crisis of mass incarceration is a daily encumbrance. These are the children, wives, boyfriends, grandmothers, nephews, and friends of the 2.3 million people who are locked up in the United States. Journalist Sylvia A. Harvey has spent time with family members of incarcerated people — having been a family member of one herself — and her recent book, The Shadow System: Mass Incarceration and the American Family, tells their stories in intimate detail.

Although many in this country still look at full prisons and see criminals rightly serving their sentence, Harvey maintains, as many others have, that the price we pay for so much incarceration can be tracked through generations of wrecked communities. She writes:

When people are incarcerated, we as a society rarely consider the lives — and the people — left behind. But their former lives don’t simply vanish. For their children, those prisoners remain parents. The collateral effects of mass incarceration cut through the immediate fabric first, then penetrate the entire extended family for generations. The most fragile of those impacted are the children.

If you’ve never met someone affected by America’s prison system, Harvey believes you should read her book. In our interview, she paints a picture of what life can look like when someone you love is behind bars. The costs, financially and emotionally, of the highest incarceration rate in the world are paid heavily by the families of the disproportionately black and poor prison population. Harvey says that this isn’t inevitable, and that the patchwork of policies and programs around the country often point to what works better, if only we can find the political will to act on it.

The Saturday Evening Post: In your book, you write about how you’ve been affected personally by incarceration. Can you talk about that?

Sylvia A. Harvey: Yeah, I experienced parental incarceration from my father for about 27 years in different California prisons. What’s been important for me, having that experience, is being able to utilize that to see what’s happening around the country to 2.3 million families, people who are directly impacted now. My father spent 27 years in prison, and that’s been significantly helpful in thinking about how policies need to change and how families are being impacted.

SEP: How did you find the families whose stories you featured in this book?

Harvey: That was actually a task. What I started to do was to call organizations from each state that was of interest for some reason. So, I picked Mississippi because of what’s happening there in terms of race relations. It is not a progressive state, so to speak. So, to look at incarceration and its impact on families in a conservative state, in a place like that, it meant calling any organizations that worked with families impacted by that. There weren’t very many programs, so it was difficult. So then I called local churches, local organizations. It was literally looking at what kinds of organizations were in place at the grassroots level.

Florida was a little bit easier because they had more organizations that worked with this demographic. I started to go along on some of the visits they had in Florida with the Children of Inmates program, going along on some of those trips and sitting in the visiting room. From doing some of that preliminary reporting, I was able to determine which families were most suitable for the book.

SEP: Could you give a rundown of the three families you covered in The Shadow System?

Harvey: In Miami, I looked at a young man, a young black man, who has a murder conviction. So, what does that mean for a young person in Miami to have this kind of conviction, and what does that mean for his daughter? In Jackson, Mississippi, now we have a family where the father has been incarcerated for 39 years. So, what does it look like to have a life sentence and to have served almost 40 years of that sentence? Being able to look back on how that manifests in his family, his three children who are all black boys. In Louisville, Kentucky, I was focusing on returning citizens, and predominately white women who were impacted by the opioid epidemic, as they returned home. So, looking at issues across the country with different demographics.

SEP: What surprised you about how other people who have been affected by incarceration live and cope with that?

Harvey: I think, the availability of resources. So, in different states you have different resources. That was — I wouldn’t say shocking — but why I decided to write the book in this way, to focus on states that are not represented often, the states we don’t really think about. It was surprising for me to see exactly how incarceration manifests. Like, how you could serve as much time as the man in Mississippi did and be able to look at other states where they’re releasing people.

I was surprised by the difference in legislation, the difference in sentencing, and the difference in resources. In Jackson, there weren’t very many resources, but if you go to Miami, there’s this program where they’re literally taking these children and their families all over the state to visit their parents in prison four times a year. This is a resource that is state-funded, so why doesn’t that exist in other parts of the country? There’s a disparity in resources available, disparity in sentencing, disparity in visitation, depending on where you are in the country.

SEP: How did visitation differ from case to case, and what does that process look like?

Harvey: In the book, my focus is on family visitation. So, family visitation was something that was taking place in Jackson, Mississippi. Family visits in that state were three to five nights, where you could literally go on prison grounds in a small apartment or trailer that’s sort of set up to mimic the idea of being home. That’s the kind of visitation I focused on because it’s obviously the most progressive visitation, and I wanted people to be able to look at that and see what that means. It means these families are able to go and feel like they’re at home again. The mother who has three children and a husband who’s been incarcerated for 39 years is able to continue to build with her partner by having these visits. That’s pretty significant. I think it’s important to be able to look at that and see what that means, what that feels like, and why it no longer exists in some states but still exists in others.

SEP: What does visitation look like in other places where they don’t have those types of programs?

Harvey: It really depends, so in some states you’ll have visitation that is behind the plexiglass, no contact, and in some places you’ll have video visits. A lot of jails are turning to video visits only, which means you’re going to the jail facility but only using video. Some visits allow contact, but it’s limited contact, so you go to the jail or prison and, for the first, maybe 15 seconds, you’re able to greet the person, give them a hug or kiss or whatever, but there’s a limitation on the physical contact you can have. Some facilities will allow you to maybe hold hands but nothing more than that. It really differs from state to state, city to city, jail to prison, it’s a broad spectrum of what can and cannot take place.

SEP: You write about the people in Kentucky who have been affected by the opioid epidemic. Can you talk about how that crisis has been handled differently than drug epidemics of the past?

Harvey: Yeah, I would say that the 1980s war on drugs — all of that legislation — literally ensured that people of color were under attack. From that alone, they were overrepresented in jails and prisons. The Anti-Drug Abuse Act of 1986 was something that really put racial minorities in a chokehold. The thinking of criminality, the idea of looking at it as something people were doing and not something happening to people. We weren’t thinking about it in the context of a health crisis. And now, we’re looking at the opioid epidemic as a health crisis. Like, “how do we fix this? How do we help people?” That was not the narrative when we had the war on drugs during the crack epidemic. It was “let’s lock all of these people up,” and I think that’s been a huge distinction.

SEP: How have companies been profiting off the increase in incarceration?

Harvey: Financial exploitation of families by the prison industry is huge. We see that in phone calls, e-mails, videos, these are all services that we on the outside are able to access quite easily. That is not the reality for people who are incarcerated. They have to pay a really high rate for these things. In Jackson, one of the families paid $6.99 for her video call that was 15 minutes. What does that mean for those families to pay that every time they want to interact with their incarcerated loved one? In some counties, it’s up to 25 dollars for a 15-minute phone call. That exists. It’s a huge industry. The going rate for hundreds of counties is 15 to 18 dollars for a 15-minute phone call. Some of these costly rates are driven up hundreds of millions of dollars by concession fees. We would call them “kickbacks.” The phone companies are paying local and state prison systems in exchange for these exclusive contracts. So, as long as they’re getting this kickback, why give them free or cheap ways to communicate?

And on top of that, we also have commissary. This is like the prison retail market. So, inside these prisons, people still need access to things. If you get a small bar of soap or if you get limited food during lunchtime or dinner, you order extra from the commissary. It’s not always that the commissary is significantly higher, but it’s high when we think about the prisoners who are paying for this. If you make four dollars a day and then you have to pay four dollars for a fungal cream, then that is exorbitant for you. Families spent $1.8 billion on commissary in a year most recently, and that’s a lot of money for families to spend. [Prison Policy Initiative found that American families spent $2.9 billion on commissary and phone calls yearly in 2017.]

I think as long as that is happening, then families will be exploited. We have to think about why it is that we can charge that. We say, to a degree, that “they can’t have cell phones” because “we don’t know what they would do with these cell phones,” but a lot of this is just financial exploitation. Private companies have found a number of ways of making sure it’s profitable. These families want to stay in touch, and if they have to go in debt trying to, that’s what you do.

SEP: Who do you think should be reading your book?

Harvey: I would say, people who are not familiar with the concept of mass incarceration and how it is impacting this country; not only people who already care about incarceration. Everyone who wants to be informed and be good citizens should be reading this book. As humans, we need to be thinking about what our country is doing, in terms of policy, that is impacting specific demographics. We need to be thinking about why it’s impacting black, brown, and poor people at such a high rate, and what that says about how we feel about those people. It needs to be read far beyond the advocates, far beyond the reformists, far beyond the directly impacted, but by those who are not familiar with what is happening but should be. We can’t continue to allow willful ignorance; I think everybody needs to demand that we have an equitable system in this country. Everyone should be reading it, and especially those who aren’t familiar with how morally bankrupt our system is.

It’s easy to give out statistics, like, “hey, 2.3 million people are incarcerated, 555,000 of those people are locked up pre-trial, which means they can’t go home because they don’t have the money,” but if you haven’t had a friend or family member face that, then you don’t understand that. So it’s easy to say that, but what does that mean? What does that look like? If I tell you a story about a young man who faces this and what that means for him, then we’re like “huh, that that’s how that works.” So I think it’s important to use narrative and storytelling to illustrate how policy is impacting people. That way, we’re able to connect to the person and understand the policy behind that.

SEP: Speaking of pre-trial, you write quite a bit about people serving long prison sentences, but we have seen jailing in the short-term increase a lot in this country, especially in rural areas.

Harvey: In Louisville, a lot of the women I interviewed were actually from eastern Kentucky. So, it’s very rural, and there’s not a lot of access to rehabilitation programs or drug or alcohol treatment that goes beyond the seven days, so they were jailed and then released to this program, The Healing Place, that allowed them to have a longer stay to really deal with this drug or alcohol issue. One of the young women in the book served 18 days, and the 18 days she served in jail impacted her heavily because while she was in jail, her children were put into foster care. Once this woman got out of jail, she figured she’d pick up her kids, but you can’t just pick up your kids once they’re in the child welfare system. She spent less than a month in jail, but once she got out she had this huge battle ahead of her, because we’re looking at the Adoption and Safe Families Act, and how it impacts families of people who are incarcerated. So, she was now up against this clock. So they gave her a case plan saying she had to complete a drug and alcohol treatment program, get a job, make visits once a week. But with the treatment program she was in, she couldn’t leave for extended periods of time to make her visits. She was in violation of her case plan because of her treatment program. So there was this conflict between whether the Department of Human Services was considering what it means for this woman and people like her who are in these kinds of programs that have a lot of stipulations and limitations, because you’re supposed to be focusing on your recovery.

So, here’s a woman who — in less than one month — her life was turned upside down because her children were taken away from her. That could accelerate her addiction, and she could lose her house, her car, her job, and then she doesn’t have anything. So, it doesn’t have to be 20 years in prison. You could be in jail for a week and lose your job. A lot of people are living paycheck to paycheck, so there’s really just one step away from their lives falling apart. One step away from no car, one step away from homelessness.

SEP: What have you been seeing in jails and prisons with the recent pandemic? Some outlets have covered the lack of response in these facilities, and the kind of crisis that could create.

Harvey: I saw that in a jail where there were more than 600 cases, they were literally writing on their windows “help us,” like, “we matter too,” crying out to the public that even if they are in there and convicted of a crime, they don’t deserve to die there because the proper precautions haven’t been taken to make sure they’re not at a greater risk to contract this virus. And we’ve seen people contracting and dying from this virus in federal prisons. There was a man who had served 44 years and he was due out this year, and he just died from COVID-19 behind bars. All of the people who work in these facilities do come back to their communities. So if you don’t think that incarcerated persons are important or valuable or that their health should be considered, think about the people who work in these facilities. This is a public health threat. Some local governments are suspending jail times for low-level violations, or reducing arrests for minor offenses. Some places are releasing pre-trial detainees. We are seeing some things happening, but it’s not happening quick enough.

Featured image: Photo by Rayon Richards.

9 Unique Activities to Keep Boredom at Bay During Quarantine

COVID-19 has forced us to remain inside, where it’s all too easy for boredom to take hold. Instead, try one of these unique activities that are perfect during this time of social distancing.

9. Parody Famous Paintings

Who knew that recreating artworks in lockdown would become the hottest social media trend of 2020? https://t.co/F0X9icY2dF pic.twitter.com/RWmtoaW5gb

— Artnet (@artnet) May 4, 2020

You have probably seen this one already, and participating is simple: find a painting online and use items around your house to replicate the outfits, setting, and props within the painting. Since this activity is designed for fun, the details do not have to be exact. Put your own unique spin on the artist’s work. When your painting is complete, take a picture and put it side-by-side with the original so you can share your creativity with others.

8. Find Inanimate Faces

What inanimate object face are you on this the 467th day of lockdown? I think I am in a perpetual state of number 6 pic.twitter.com/alyfOfGrRi

— James (@Shabby_Dad) March 31, 2020

You may have never noticed it, but faces can be spotted amongst many household items. For instance, the pillows on your couch might form eyes, or the cord on your chandelier possibly creates a long nose. This activity taps into your imagination and will send you on a scavenger hunt throughout your entire house. More than likely, you won’t look at any of those objects the same way again.

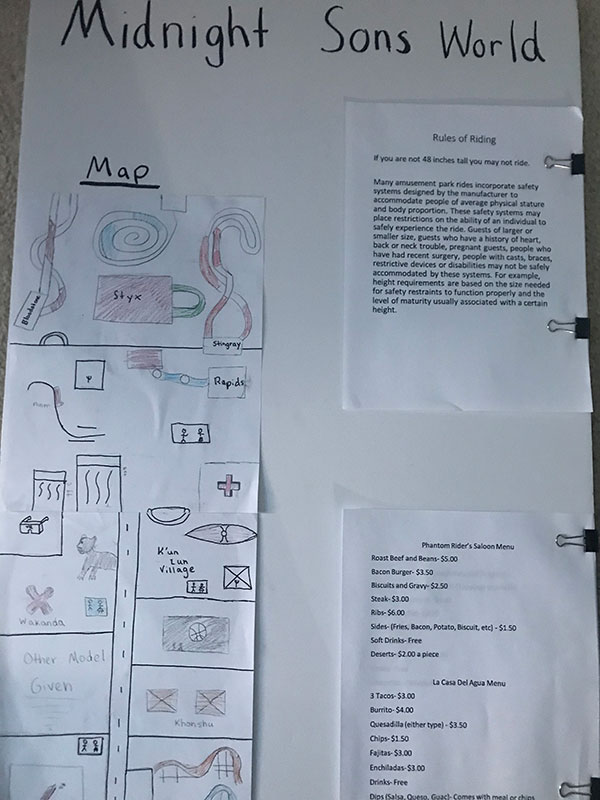

7. Design an Amusement Park

If you are a parent, this activity is a great way to keep your kids occupied, but it’s also fun for adults. Designing an amusement park allows people to see what it would be like to be an Imagineer at Disney theme parks or a Universal Creative team member. In this venture, you’ll come up with the name of an all new theme park, as well as its location, attractions, rides, and restaurants. What makes your park unique? What characters can you meet throughout? Does the park have a gift shop? How much does your park cost? There are endless ways to execute this project. Here’s one lesson plan to get you started.

6. Play Balloon Spikeball

Spikeball is an exciting outdoor game where players bounce a medium-sized ball off a net in an attempt to score points against other players. But Spikeball can be adapted to work indoors as well; just replace the ball with a balloon. One tip: bring a few extra balloons, in case somebody gets carried away.

5. Dress Up with Your Family

Best Family Costumes😂 pic.twitter.com/hUoCTYkOTp

— ZuZuQ🌹9️⃣ (@ZuZuQ5) May 4, 2020

People — sometimes entire families — are dressing up each day in accordance with a daily theme, sometimes oriented around a holiday, a color, a movie — any topic will do. Another adaptation is where each person chooses what another family member wears to dinner. Just put the names of everyone in a cup and draw to see who designs whose outfit. Like other items on this list, this activity is open to interpretation and can be changed to fit your group’s unique ideas and interests.

4. Go on a Scavenger Hunt

Scavenger hunts are a classic. Find some unique or unusual items, then hide them around the interior and possibly the exterior of your house. See who can find the most items. Put a prize on the line, or just play for fun. It is like an Easter egg hunt, but with more variety. Check out these ideas for adults and children.

3. Create a Harry Potter Escape Room

Use your knowledge of the Harry Potter series to create an immersive experience for your friends or family, whether in an escape room format (find and solve clues to escape the room) or an Amazing Race format (go to different locations throughout your home and complete challenges, getting clues in order to reach the finish line). Either way, incorporate different things from the books, like the magical creatures, Deathly Hallows, Hogwarts classes, or whatever else you desire. This example from Peters Township Public Library can provide inspiration. This same activity can also be completed with a plethora of other books and movies.

2. Try Your Hand at Trivia

Pick a collection of categories and design the questions and answer choices to go along with it. There are multiple ways to do this. Kahoot, Quizziz, and Gimkit are great for creating trivia games. You can also draw a Jeopardy board or pull random questions out of a hat. You can even set up a video conference to play with socially distanced friends and relatives.

1. Film “A Day in the Life” Videos

With so many entertaining options for quarantine, you need a way to remember them. Film yourself and those around you participating in their quarantine activities. Are your parents cooking a new dish? Film it. Going on a scavenger hunt? Film it. Building a puzzle? Film it, but maybe time lapse is better for that one. You can edit the videos together and have your own documentary to commemorate quarantine.

Featured image: Shutterstock.