What was America’s First Successful Book Series?

In the portfolio of a company’s offerings, there are no crown jewels more prized than the franchise. The roots of serial storytelling stretch all the way back to oral tradition, but the birth of publishing built on that tradition of long-term narratives and allowed them to flourish. That leads to two questions: what was the first completely American novel sequence to capture the attention of the young U.S., and how does it connect to, you guessed it, The Saturday Evening Post?

Many literary historians agree that the first real novel sequence was the French work Artamène ou le Grand Cyrus (usually called Artamène or Cyrus the Great in English). The first volume was published by Georges de Scudéry in 1649, though his sister Madeleine was the actual author, or at the very least, a significant co-author. The siblings put out ten volumes of the story, which cast contemporary people in roles associated with stories from myth and religion. At over 13,000 pages and nearly two million words, it remains one of the longest works of its type ever published.

Moving on a couple of centuries, we find James Fenimore Cooper. Born in New Jersey just days after the end of the Revolutionary War, he started at Yale when he was thirteen, but was kicked out for a pranks like locking a donkey in a classroom and destroying the door to a fellow student’s room. However, Cooper turned his youthful ways around and became an officer in the United States Navy. In 1811, he married Susan Augusta DeLancey.

The marriage would have a profound impact on Cooper’s direction in life, as a couple’s activity led to a major career change. While reading a novel aloud to his wife (as family reading was a common diversion at that time), Cooper realized that he had his own interest in storytelling. That revelation led to the writing of his first book, Precaution. The book was issued anonymously in 1820 and was well-received in both England and the U.S. His next book, 1821’s The Spy, turned out to be a major success, establishing him as the first American bestselling author; based on stories told him by his neighbor (and United States Founding Father) John Jay, Cooper’s The Spy combined two things that would be at the forefront of his most successful works: historical settings and action.

Cooper’s third novel would mark the beginning of a landmark series. 1823’s The Pioneers introduced readers to Nathaniel “Natty” Bumppo, also known by such names as Leatherstocking and Hawkeye, and his close Mohican friend, Chingachgook (who sometimes uses the name John Monegan). First appearing on the page as old men, Bumppo and Chingachgook have rich histories as scouts who help the settlers in the area. Cooper may have based Bumppo on the exploits of frontiersman Daniel Boone, who was already an American folk hero.

Though he would continue to write a diverse array of material including nonfiction history, Cooper returned to Bumppo and Chingachgook four more times between 1826 and 1841. The novels did not arrive in chronological order; rather, they skipped up and down the timeline of Bumppo’s life. While The Prairie, The Deerslayer, and The Pathfinder would all find popular success, it was the second book (both in terms of release and in the series continuity), 1826’s The Last of the Mohicans, that would prove to be Cooper’s most popular and enduring work.

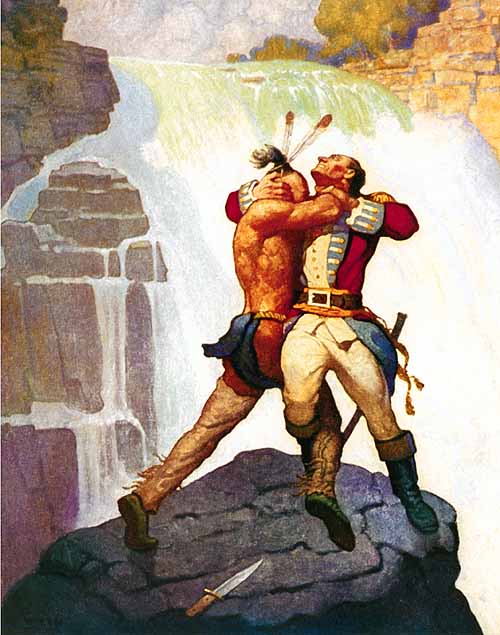

The Last of the Mohicans took place around 1757 during the French and Indian War, which is the name typically associated with the battles of the Seven Years War between England and France that occurred in North America. During the conflict, both countries enlisted Native American tribes as allies to support the troops that each had landed on the continent. Settlers along the frontier who had arrived from England or were descended from earlier settlers frequently fought in England’s colonial militias. It is against this backdrop, and the historically accurate siege of Britain’s Fort William Henry by the French, that Cooper set his novel.

The Last of the Mohicans (1992) trailer (Uploaded to YouTube by TrailersPlaygroundHD)

The main events of the plot concern Hawkeye, Chingachgook, and Chingachook’s adult son Uncas guiding and protecting Cora and Alice Munro, the daughters of British Colonel Munro. British Major Duncan Heyward and singing master David Gamut are also part of their party, who frequently come in conflict with the Huron chief Magua, a secret ally of the French. The wilderness adventure aspect of the tale, combined with historical events, made the book extremely popular. Magua was one of the early, effective villains of American literature, and the story cemented the three central companions as significant heroes to the audience. Since 1909, there have been at least 10 American film adaptations of the work, as well as versions made for radio, television, comics, and opera; such is the story’s reach that it’s also been adapted for film in Europe several times, once as a German silent version in 1920 that featured Bela Lugosi (yes, you read that right) as Chingachgook.

Apart from his extremely popular Leatherstocking series, Cooper’s output was very diverse. He often infused his stories with social and political commentary, whether he was writing about maritime adventure or history. As an admirer of Thomas Jefferson, and a writer who wove that admiration into his work, Cooper often came under attack from political opponents in the Whig party. Cooper regularly sued his attackers for libel and won, which only created more enemies. The author more or less shrugged his shoulders and soldiered on. In additional to his novels, he published an array of short fiction, some of which ran in The Saturday Evening Post (including “Life Before the Mast,” which appeared in The Saturday Evening Post in 1843; you can read that story below).

When Cooper died in 1851, a number of famous fellow writers took it upon themselves to make sure that he was remembered for his expansive work. Everyone from Henry David Thoreau to D.H. Lawrence praised him, and Washington Irving spoke at one of his memorials. Over time, most of his works have faded from popular awareness, but the Leatherstocking Tales, particularly The Last of the Mohicans, carved out a seemingly immortal space. Cooper proved that a wholly American series of fiction could find popular success not only in his home country, but around the world. It’s appropriate that he wrote about guides and pioneers, because he opened a whole new frontier for American writers to explore.

“The Eyes of Asia: The Fumes of the Heart” by Rudyard Kipling

Although he was widely regarded as one of the most famous British authors of all time, Rudyard Kipling’s birthplace was across the world from the British Isle in what was then known as British India. Kipling drew upon his upbringing in Bombay as inspiration for many of his most famous works including The Jungle Book (1894) and Kim (1901). The first English-speaker to win the Nobel Prize in Literature harkened back to his childhood in his novel The Eyes of Asia, about a Sikh Man’s experience fighting in World War I for the British.

Published on May 19, 1917

SCENE: Pavilion and Dome Hospital, Brighton — 1915. What talk is this, Doctor Sahib? This Sahib says he will be my letter writer? Just as though he were a bazar letter writer? … What are the Sahib’s charges? Two annas? Too much; I give one. . . . No! No! Sahib! You shouldn’t have come down so quickly. You’ve forgotten; we Sikhs always bargain … Well, one anna be it. I will give a bond to pay it out of my wound-pension when I get home. Sit by the side of my bed …

This is the trouble, Sahib: My brother, who holds his land and works mine outside Amritsar City, is a fool. He is older than I. He has done his service and got one wound out of it in what they used to call war — that child’s play in the Tirah. He thinks himself a soldier! But that is not his offense. He sends me post cards, Sahib — scores of post cards — whining about the drouth, or the taxes, or the crops, or our servants’ pilferings, or some such trouble. He doesn’t know what trouble means. I want to tell him he is a fool … What? True! True, one can get money and land, but never a new brother. But for all that, he is a fool … Is he a good farmer? Sa-heeb! If an Amritsar Sikh isn’t a good farmer a hen doesn’t know an egg … Is he honest? As my own pet yoke of bullocks. He is only a fool. My belly is on fire now with knowledge I never had before, and I wish to impart it to him — to the village elders — to all people. Yes, that is true too. If I keep calling him a fool he will not gain any knowledge … Let me think it over on all sides. Aha! Now that I have a bazar writer of my own, I will write a book — a very book to my fool of a brother … And now we will begin. Take down my words from my lips to my foolish old farmer brother:

“You will have received the notification of my wounds which I took in Franceville. Now that I am better of my wounds, I have leisure to write with a long hand. Here we have paper and ink at command. Thus it is easy to let off the fumes of our hearts. Send me all the news of all the crops and what is being done in our village. This poor parrot is always thinking of Kashmir.

“As to my own concerns, the trench in which I sat was broken by a bomb-golee as large as our smallest grain chest.” [He’ll go off and measure it at once!] “It dropped out of the air. It burst, the ground was opened and replaced upon seven of us. I and two others took wounds. Sweetmeats are not distributed in wartime. God permitted my soul to live, by means of the doctors’ strong medicines. I have inhabited six hospitals before I came here to England. This hospital is like a temple. It is set in a garden beside the sea. We lie on iron cots beneath a dome of gold and colors and glittering glasswork, with pillars.” [You know that’s true, Sahib. We can see it — but d’you think he’ll believe? Never! Never!] “Our food is cooked for us according to our creeds — Sikh, or Brahmin, or Mussulman, and all the rest. When a man dies he is also buried according to his creed. Though he has been a groom or a sweeper, he is buried like some great landowner. Do not let such matters trouble you henceforth. Living or dying, all is done in accordance with the ordinance of our faiths. Some low-caste men, such as sweepers, counting upon the ignorance of the doctors, make a claim to be of reputable caste in order that they may get consideration. If a sweeper in this hospital says he is forbidden by his caste to do certain things he is believed. He is not beaten.” [Now, why is that, Sahib? They ought to be beaten for pretending to caste, and making a mock of the doctors. I should slipper them publicly — but — I’m not the Government. We will go on.]

“The English do not despise any sort of work. They are of many castes, but they are all one kind in this. On account of my wounds I have not yet gone abroad to see English fields or towns.” [It is true I have been out twice in a motor carriage, Sahib, but that goes too quickly for a man to see shops, let alone faces. We will not tell him that. He does not like motor cars.] “The French in Franceville work continually without rest. The French and the Phlahamahnds-Flamands — who are a caste of French, are kings among cultivators. As to cultivation” — [Now, I pray, Sahib, write quickly for I am as full of this matter as a buffalo of water] — “their fields are larger than ours, without any divisions, and they do not waste anything except the width of the footpath. The land descends securely from father to son upon payment of tax to the Government, just as in civilized countries. I have observed that they have their land always at their hearts and in their mouths, just as in civilized countries. They do not grow more than one crop a year, but this is recompensed to them because their fields do not need irrigation. The rain in Franceville is always sure and abundant and in excess. They grow all that we grow, such as peas, onions, garlic, spinach, beans, cabbages and wheat. They do not grow small grains or millet, and their only spice is mustard. They do not drink water, but the juice of apples, which they squeeze into barrels for that purpose. A full bottle is sold for two pice. They do not drink milk, but there is abundance of it. It is all cows’ milk, of which they make butter in a churn, which is turned by a dog.” [Now, how shall we make my brother believe that? Write it large.] “In Franceville the dogs are both courteous and industrious. They play with the cat, they tend the sheep, they churn the butter, they draw a cart and guard it too. When a regiment meets a flock the dogs of their own wisdom order the sheep to step to one side of the road. I have often seen this.” [Not one word of this will he or anyone in the villages believe, Sahib. What can you expect? They have never even seen Lahore City! We will tell him what he can understand.] “Plows and carts are drawn by horses. Oxen are not used for these purposes in these villages. The fieldwork is wholly done by old men and women and children, who can all read and write. The young men are all at the war. The war comes also to the people in the villages, but they do not regard the war because they are cultivators. I have a friend among the French — an old man in the village where the Regiment was established, who daily fills in the holes made in his fields by the enemy’s shells with dirt from a long-handled spade. I begged him once to desist when we were together on this work, but he said that idleness would cause him double work for the day following. His grandchild, a very small maiden, grazed a cow behind a wood where the shells fell, and was killed in that manner. Our Regiment was told the news and they took an account of it, for she was often among them, begging buttons from their uniforms. She was small and full of laughter, and she had, learned a little of our tongue.” [Yes. That was a very great shame, Sahib. She was the child of us all. We exacted a payment, but she was slain — slain like a calf for no fault. A black shame! . . . We will write about other matters.]

“As to cultivation, there are no words for its excellence or for the industry of the cultivators. They esteem manure most highly. They have no need to burn cow dung for fuel. There is abundance of charcoal. Thus, not irrigating or burning dung for fuel, their wealth increases of itself. They build their houses from ancient times round about mountainous dung heaps, upon which they throw all things in season. It is a possession from father to son, and increase comes forth. Owing to the number of army horses in certain places there arises very much horse dung. When it is excessive the officers cause a little straw to be lit near the heaps. The French and the Phlahamahnds, seeing the smoke, assemble with carts, crying: ‘What waste is this?’ The officers reply: ‘None will carry away this dung. Therefore, we burn it.’ All the cultivators then entreat for leave to carry it away in their carts, be it only as much as two dogs can draw. By this device horse lines are cleaned.

“Listen to one little thing: The women and the girls cultivate as well as the men in all respects.” [That is a true tale, Sahib. We know — but my brother knows nothing except the road to market.] “They plow with two and four horses as great as hills. The women of Franceville also keep the accounts and the bills. They make one price for everything. No second price is to be obtained by any talking. They cannot be cheated over the value of one grain. Yet of their own will they are generous beyond belief. When we came back from our work in the trenches they arise at any hour and make us warm drinks of hot coffee and milk and bread and butter. May God reward these ladies a thousand times for their kindness! But do not throw everything upon God. I desire you will get me in Amritsar City a carpet, at the shop of Davee Sahai and Chumba Mall — one yard in width and one yard and a half in length, of good color and quality to the value of forty rupees. The shop must send it with all charges paid, to the address which I have had written in English character on the edge of this paper. She is the lady of the house in which I was billeted in a village for three months. Though she was advanced in years and belonged to a high family, yet in the whole of those three months I never saw this old lady sit idle. Her three sons had gone to the war. One had been killed; one was in hospital; and a third, at that time, was in the trenches. She did not weep or wail at the death or the sickness, but accepted the dispensation. During the time I was in her house she ministered to me to such an extent that I cannot adequately describe her kindness. Of her own free will she washed my clothes, arranged my bed, and polished my boots daily for three months. She washed down my bedroom daily with hot water, having herself heated it. Each morning she prepared me a tray with bread, butter, milk and coffee. When we had to leave that village that old lady wept on my shoulder. It is strange that I had never seen her weep for her dead son, but she wept for me. Moreover, at parting she would have had me take a fi-farang note for expenses on the road.” [What a woman! What a woman! I had never believed such women existed in this black age.]

“If there be any doubt of the quality or the color of the carpet ask for an audience of the Doctor Linley Sahib, if he is still in Amritsar. He knows carpets. Tell him all I have written concerning this old lady — may God keep her and her remaining household! — and he will advise. I do not know the Doctor Sahib, but he will overlook it in wartime. If the carpet is even fifty rupees, I can securely pay out of the monies which our lands owe me. She is an old lady. It must be soft to her feet, and not inclined to slide upon the wooden floor. She is well-born and educated.” [And now we will begin to enlighten him and the elders!]

“We must cause our children to be educated in the future. That is the opinion of all the Regiment, for by education even women accomplish marvels, like the women of Franceville. Get the boys and girls taught to read and write well. Here teaching is by Government order. The men go to the war daily. It is the women who do all the work at home, having been well taught in their childhood. We have yoked only one buffalo to the plow up till now. It is now time to yoke up the mulch buffaloes. Tell the village elders this and exercise influence.” [Write that down very strongly, Sahib. We who have seen Franceville all know it is true.]

“But as to cultivation: The methods in Franceville are good. All tools are of iron. They do not break. A man keeps the tools he needs for his work and his repairs in his house under his own hand. He has not to go back to the village a mile away if anything breaks. We never thought, as these people do, that all repairs to tools and plows can be done on the very spot. All that is needed when a strap breaks is that each plowman should have an awl and a leather cutter to stitch the leather. How is it with us in our country? If leather breaks we farmers say that leather is unclean, and we go back from the fields into the village to the village cobbler that he may mend it. Unclean? Do not we handle that same thing with the leather on it after it has been repaired? Do we not even drink water all day with the very hand that has sweated into the leather? Meantime we have surely lost an hour or two in coming and going from the fields.” [He will understand that. He chatters like a monkey when the men waste time. But the village cobbler will be very angry with men!] “The people of Franceville are astonished to learn that all our land is full of dogs which do no work — not even to keep the cattle out of the tilled fields. Among the French, both men and women and little children occupy themselves with work at all times on the land. The children wear no jewelry, but they are more beautiful than I can say. It is a country where the women are not veiled. Their marriage is at their own choice, and takes place between their twentieth and twenty-fifth year. They seldom quarrel or shout out. They do not pilfer from each other. They do not tell lies at all. When calamity overtakes them there is no ceremonial of grief, such as tearing the hair or the like. They swallow it down and endure silently. Doubtless, this is the fruit of learning in youth.”

[Now we will have a word for our Guru at home. He is a very holy man. Write this carefully, Sahib.] It is said that the French worship idols. I have spoken of this with my old lady and her Guru [priest]. It is not true in any way. There are certainly images in their shrines and deotas [local gods] to whom they present petitions as we do in our home affairs, but the prayer of the heart goes to the God Himself. I have been assured this by the old priests. All the young priests are fighting in the war. The Frenchmen uncover the head but do not take off the shoes at prayer. They do not speak of their religion to strangers, and they do not go about to make converts. The old priest in the village where I was billeted so long said that all roads, at such times as these, return to God.” [Our Guru at home says that himself; so he cannot be surprised if there are others who think it.] “The old priest gave me a little medal which he wished me to wear round my neck. Such medals are reckoned holy among the French. He was a very holy man and it averts the evil eye. The women also carry holy beads to help keep count of their prayers.

“Certain men of our Regiment divided among themselves as many as they could pick up of the string of beads that used to be carried by the small maiden whom the shell slew. It was found forty yards distant from the hands. It was that small maiden who begged us for our buttons and had no fear. The Regiment made an account of it, reckoning one life of the enemy for each bead. They deposited the beads as a pledge with the regimental clerk. When a man of the guarantors was killed, the number of his beads which remained unredeemed was added to the obligation of the guarantors, or they elected an inheritor of the debt in his place.” [He will understand that. It was very correct and businesslike, Sahib. Our Pathan Company arranged it.] “It was seven weeks before all the beads were redeemed, because the weather was bad and our guns were strong and the enemy did not stir abroad after dark. When all the account was cleared, the beads were taken out of pawn and returned to her grandfather, with a certificate; and he wept.

“This war is not a war. It is a world-destroying battle. All that has gone before this war in this world till now has been only boys throwing colored powder at each other. No man could conceive it. What do you or the Mohmunds or anyone who has not been here know of war? When the ignorant in future speak of war I shall laugh, even though they be my elder brethren. Consider what things are done here, and for what reasons.

A little before I took my wounds, I was on duty near an officer who worked in wire and wood and earth to make traps for the enemy. He had acquired a tent of green cloth upon sticks, with a window of soft glass that could not be broken. All coveted the tent. It was three paces long and two wide. Among the covetous was an officer of artillery in charge of a gun that shook mountains. It gave out a shell of ten maunds or more [eight hundred pounds]. But those who have never seen even a rivulet cannot imagine the Indus. He offered many rupees to purchase the tent. He would come at all hours increasing his offer. He overwhelmed the owner with talk about it.” [I heard them often, Sahib.] “At last, and I heard this also, that tent owner said to that artillery officer: ‘I am wearied with your importunity. Destroy today a certain house that I shall show you, and I will give you the tent for a gift. Otherwise, have no more talk.’ He showed him the roof of a certain white house which stood back three kos [six miles] in the enemy country, a little underneath a hill with woods on each side. Consider this, measuring three kos in your mind along the Amritsar Road. The gunner officer said: ‘By God, I accept this bargain!’ He issued orders and estimated the distance. I saw him going back and forth as swiftly as a lover. Then fire was delivered and at the fourth discharge the watchers through their glasses saw the house spring high and spread abroad and lie upon its face. It was as a tooth taken out by a barber. Seeing this the gunner officer sprang into the tent and looked through the window and smiled because the tent was now his. But the enemy did not understand the reasons. There was a great gunfire all that night, as well as many enemy regiments moving about. The prisoners taken afterward told us their commanders were disturbed at the fall of the house, ascribing it to some great design on our part; that their men had no rest for a week. Yet it was all done for a little green tent’s sake.

“I tell you this that you may understand the meaning of things. This is a world where the very hills are turned upside down, with the cities upon them. He who comes alive out of this business will forever after be as a giant. If anyone wishes to see it let him come here or remain disappointed all his life.”

[We will finish with affection and sweet words. After all, a brother is a brother.] “As for myself, why do you write to me so many complaints? Are you fighting in this war or I? You know the saying: A soldier’s life is for his family; his death is for his country; his discomforts are for himself alone. I joined to fight when I was young. I have eaten the Government’s salt till I am old. I am discharging my obligation. When all is at an end the memory of our parting will be but a dream.

“I pray the Guru to bring together those who are separated. God alone is true. Everything else is but a shadow.”

[That is poetry. Oh — and add this, Sahib:]

“Let there be no delay about the carpet. She would not accept anything else.”

Featured image illustrated by Harvey Dunn, SEPS

We Become Nothing

We got off the bus in Göreme and found a room in the Kervansaray Otel. I was sick. The Kervansaray’s owners, a father and son both first-named Kemal, were troubled by my presence, alone, when Luke left. He said he was going to find me some crackers and bottled water, but he was gone for what seemed a very long time. We were the hotel’s only guests.

The Kemals walked up and down the hallway, checking on me. I lay shivering and burning up in bed and being sick into a T-shirt because I didn’t want to go past them to the bathroom. I watched their shadows against a sheet of textured gray plastic in the corridor wall. That plastic was compensation for having no window to the outside; it let some light in, but it also trapped me in place because I couldn’t hide. I even saw one Kemal bend down to peer through the keyhole, which was the old-fashioned kind with a big gap. I was sure they thought there was something wrong beyond the usual illnesses that seize tourists, and knowing that they suspected this made me feel guilty, even though I had done nothing.

The Kemals were relieved when Luke came back and took charge of me. I was relieved too. His breath smelled like sesame seeds. I rinsed my mouth with the bottled water he’d brought me.

“Better,” I said. “Better.”

The Kemals fetched glasses of tea for both of us. We stood in the plastic-lined hallway and drank politely, smiling warily at each other.

Luke and I had already had tea all over Turkey, given us by hoteliers and merchants and, yesterday, an elderly couple in Ankara who beckoned us into their plywood shack during a sudden snow flurry. Their çay might have been the reason my stomach was churning now, or at least part of the reason. I’d also eaten some carrot shavings with a kebab, though I’d been warned that fresh vegetables were dangerous. I thought I’d been to worse places and had ingested dirtier things.

When our glasses were empty, Luke did not want to stay inside. “Let’s take a walk,” he said. “Get you some fresh air, see the sunset. There are caves up the hill.”

“I don’t know how far I can go,” I said. Having him back and drinking some tea had settled my stomach a little but not enough.

The Kemals encouraged us. The son said, “The path is called Hill of Dreams.” The father said, “Some peoples lives in the caves.”

We had come to see the underground cities and bright-painted cave churches, jewels of Cappadocia. We hadn’t come to lie sick in hotel rooms by ourselves. So I changed into a long skirt and my last clean shirt, and I tied a scarf over my dirty hair.

“Good-bye,” the Kemals called after us in English. “Good-bye, good-bye!”

The hotel was on the edge of town. Luke and I walked up the Hill of Dreams, toward a giant silhouette of Atatürk done in black wire. His portrait was everywhere because he was the father of modern Turkey. We found a rock that would let us gaze through Atatürk to the sunset, and Luke took off his sweater and folded it for me to sit on. He put his arm around me in that way the guidebook told us not to do where we could be seen, and we leaned into each other.

On this trip, we had been highlighting Rumi’s poetry: The wound is the place where the Light enters you. And Your task is not to seek for love but to find the barriers that you have built against it. And Become nothing, and he’ll turn you into everything.

We were ready. To become everything, because we knew how it was to be nothing. We were making ourselves into new people in a place where almost all temptation was banned. Military police strolled the city streets in olive fatigues, and we were constantly afraid of being arrested. We knew that we hadn’t yet shed that wild-eyed, hungry look of people on the brink. We also knew that if you’re in the habit, you always know where to find more. Miles and miles of poppy fields stretched across the interior.

There were no police on the Hill of Dreams. It was the most alone we had been since landing. Luke kept a casual hold of my shoulders as if I did not need him to prop me up, and I tried very hard not to be sick.

When the sunset began to edge the clouds yellow and pink, Luke reached in his pocket and dropped a box into my lap. It was covered in coarse red velvet and it looked to me like a small, bloody animal.

“I found it in the village this afternoon,” he said. “When something is perfect, you don’t wait.”

What should a person say to that? “We agreed on a year.”

Luke misinterpreted. He said, “Don’t think you aren’t lovable, because you are. By me.”

We had been told that my insecurity was as big a problem as any other addiction. I wasn’t sure I believed that, but I was insecure enough not to question it. On this trip, Luke had given me some encouragement every day, usually in a way that reinforced a bad feeling: Don’t think you aren’t lovable felt like Nobody but me will ever love you. I supposed he would promise something like this in his vows.

“Go on, look inside!” Luke picked up the box and was about to open it himself when a coincidence came along.

An old man, or possibly one in late middle age, shuffled quiely up the path with a steadiness that must have come of a lifetime treading unstable ground. He wore a black fez and pants baggy to the knees, with a long, once-white shirt. Everything about him was loose and thin and barely held together.

I shrugged my way out of Luke’s embrace; I didn’t want to offend with public touching. But the man did not look at us. He came very close, yet kept his face pointed forward.

At first I was glad for the interruption, and then I was gladder when he stopped a few yards up the path. He made a clicking sound and flicked his fingers toward his body.

“Let’s go,” I said. I handed the box back to Luke. It was unlike me to be so impulsive, but I wanted to be anywhere the proposal was not.

Luke was torn. He mumbled, “I think I saw that guy in the village today. He was at a café or something.”

Anytime Luke was vague, I worried about what he did not want to tell me. He didn’t seem to have the same concerns about me, and that worried me in a different way.

Up ahead, the stranger waited. He flicked his fingers toward himself once more.

“Come on,” I said, “when are we ever going to meet someone like him again?” Even the old couple in Ankara had worn T-shirts, and they had a television.

Luke put the box back in his jeans. “Okay.” He helped me stand and we followed the stranger. It was good to be moving around, though I felt wobbly.

The man led us to a slope of crumbly karst, onto which he stepped as lightly and surely as a carpet. I hesitated. The slope was steep and I was tired from being sick; there was a perfectly good path we could have taken instead.

I tried out the languages of which I knew a little: “Français, Deutsch, español, English?” I wanted to ask about the path. “Yok?” I finished. No, nothing?

He didn’t answer. Luke took a step onto the karst, slid down, stepped up again, and held out his hand. I didn’t want this adventure anymore, but I felt I had to go too, since I had started it.

In this circumstance, it was all right to touch. We held hands and slipped and skidded, but our guide barely dislodged any pebbles.

It would be natural to seek one of Rumi’s lessons here, in the accidental encounter, the silent old man passing lightly through life. I tried. I was tired but I tried because I really wanted to believe that all of this meant something. I still didn’t feel great.

Luke pulled me the last few feet, onto a flat, terraced area. Incredibly, what we saw was worth all the effort. An old red-and-yellow wooden cart was parked there with a couple of goats tied to its wheels, and a handful of women in dark skirts and headscarves sat on the edge of a well, smoking cigarettes. They were surrounded by skinny cats twitching their tails like dogs. Behind, the cave mouths expanded as the sky colored orange. It was a picture from a fairy tale, a scene printed on brochures to lure tourists.

And it was here that our host at last showed his face. He turned to us, spreading his arms as if in a blessing.

I tried not to be sick again. The side we hadn’t seen was a knot of scar tissue and collapsed bone. It glowed vermilion in the dying light. And he had no left eye.

I remembered that line of Rumi: The wound is the place where the Light enters you. And I thought, What bullshit. What utter bullshit. I could not begin to imagine what had happened to this man, and I wanted to sympathize with him—but he frightened me.

We pretended we were merely tired. I took off my scarf to blot my face dry. Luke brushed the dirt off the thin cloth of my skirt.

The one-eyed man watched him touch me. So did the women.

I thought, Maybe one of them is his wife. I tried smiling. If they called out a welcome, then I would feel okay. I would stop feeling self-conscious and scared and that other emotion that was creeping in. Foreboding. Shame — the old excuse for so much I’d done.

The women stared stone-faced at the sky. They were not welcoming us. I looked at Luke, pleading; the stranger looked at him too.

Luke pointed down a trail that hugged the hillside and the line of caves, and he asked slowly, “You … live … here?”

So that was where the man took us. I didn’t want to go; I lagged behind as Luke set off. Then the old man wrapped his hand around my wrist. He tugged. I wanted him to let go, but when I pulled away he pulled harder toward, and Luke was already well down the path.

I was glad to escape from the women, at least.

We marched past a series of small caves. The doorways were low and didn’t always have actual doors in them; smells of cooking and mildew and smoke lingered around the openings, and what we could see of the dark interiors was all furnished with stacks of crates and clothing hung up on poles. Luke fell behind, peering inside each one. When I tripped, it was the stranger who steadied me.

“So cool!” I heard Luke say. His voice echoed; he was speaking into somebody’s home.

I wanted to shout at him to hurry up. And shut up. But would that have helped?

Suddenly we were at the last cave, or at least the last we could see. It was isolated around a curve and its path had crumbled away. Even from the outside it reeked of urine.

The one-eyed man ducked inside. I ducked, too, just in time to avoid knocking my head hard on the rock as he pulled me after him.

In the past, our habits had taken Luke and me to some dirty squats and alleys, but none had made me as queasy as this. Maybe some of them should have, but back then I’d been just too far gone to know what to feel. You might think places like this would have nothing you want, but in our experience they were the only ones that did.

The cave was a home. Or at least it was a crash pad. It had a blanket on the floor, and a pillow, and a few plastic crates packed with clothes and bottles. The floor was all dirt. The ceiling was low.

My stomach lurched. The old man had swung me around and now stood between me and the door.

Now he spoke for the first time, in a voice that was low and rough and missing some tones. It came as a shock. I could not recognize a syllable and I had never been so afraid.

“Que voulez-vous?” I tried. “Was möchten Sie?” I mangled the phrase Turkish waiters said in cheap restaurants: “Ne istiyorsun? What do you want?”

I got the words out just as Luke slid in and stood next to me, bumping my shoulder in a gesture that was just friendly but I hoped would look protective.

In English, the old man said, “Mon-ey.”

In a way it was a relief.

“He thinks we’re rich,” I said to Luke. “He must have seen you in town today.” That might have been mean of me to say, but it was true; Luke could get careless when excited, and he did like to impress people.

What I did not say was that the stranger thought we were addicts. I did not need to say it. We could not have been the first people he’d lured up the hill, and we were addicts.

Right now I wanted nothing more than to sink into it again. My nerves stung with craving.

“Mon-ey!” the man repeated impatiently. He seemed to grow larger, filling the space between us and the cave mouth. He flicked his fingers in that Come here gesture. This time I thought it meant Pay up.

I dug into my skirt pocket. Luke let go of me to search his own pockets, but I’d have bet they held nothing but the red velvet box. I found a few coins and a bill worth one thousand lira. Maybe I could just hand that over and go. We wouldn’t take anything; we’d just pay.

The coins hit the ground. “Yok!” Our host had smacked my hand hard.

Then he reached into his own pants. He pulled out coins of his own and threw them at me. They bounced off my shoulders, my breasts, my arms. They slid down my clothes and my skin.

Oh, I thought. Oh.

I couldn’t speak, couldn’t look at Luke now, could only feel so full of longing that it made me retch. The one thing that would stop the retching was the thing I had vowed not to have.

“Yok!”

I had been digging in my pocket again, hoping to find it suddenly full. The one-eyed man grabbed my arm and shook hard. Then let me go, so he could make a circle with one thumb and forefinger. He plunged the other index finger inside.

At the height of our habit, I had been careless with my body and Luke did not mind. He encouraged it, in fact; he expected it. I had been lovable (he’d told me so even back then, in the worst of it) but my body did not matter. So I had been an easy trade for whatever was on offer.

Now things were different. Now we knew this: The body is not hidden from the soul, nor is the soul hidden from the body.

I felt in my bones that this was the moment. The moment at which we would have to become everything to each other, because Luke had to fight for me as he’d fought for his own life.

But he didn’t. He stood agape, staring at the coins in the dust.

A hand closed on my crotch. I felt it through the thin skirt, bruising me. The old man was faster than he seemed.

“Evet,” he said, “bu.”

Yes, this.

Almost the worst part was getting away. Tripping and sliding and battering myself against the cliffside, aching all over, and not just where I’d been grabbed, where the feel of a strange hand would linger long after I’d escaped. Vomiting into the dirt and my own hair, scattering the underfed cats. I tried to run past the women, who stared frankly through the smoke of their cigarettes; they knew exactly what had happened, or they thought they did.

Luke stumbled along a few feet behind me. He was the one who was crying. He called out to me that he was sorry and he hated himself, over and over, like a chant. What he needed was for me to say I forgave him and to take the blame, but I didn’t. I lurched away.

So I fell down the Hill of Dreams toward a purple, star-speckled sky, where Atatürk’s profile was lit up in red neon and held the most beautiful moon inside.

The Kemals brought me tea and some bumpy crackers. They brought warm wet towels and looked away as I washed the blood from my cuts. They did not ask questions, not even about Luke. He had vanished somewhere behind me; I suspected he was looking for a café that sold anisette raki or some other drink. He wasn’t choosy.

The Kemals brought a telephone.

“You call to your father,” they told me. “You call to your mother.”

They wanted me gone so badly.

I thought they must know the strange man. They could have told me who he was, how he lost his eye, how many other fools he’d led up to his cave. How many women he’d wrestled to the ground, how many times he’d succeeded. Mon-ey. It had extra meanings here.

I didn’t ask. I knew that no matter what I told them, they would think this was not the old man’s fault. In all other eyes, fault was ours, for being what we were. Maybe the Kemals had even steered us toward the caves, thinking I needed to stop a withdrawal. Maybe they had told the old man to go find us. No one seemed safe to me now.

I called Turkish Air and found out I could take a bus to Antalya that night and then a plane home. It would cost everything I had left, and in a way I was pleased. Now I would have all I deserved; I would have nothing.

While I was packing in the light of a dim one-bulbed lamp, Luke turned up at last. His face was flushed and he reeked of anisette. That much was inevitable.

But somewhere he’d discovered that he still had hope. He watched me stuffing my laundry into my backpack, and he tossed the red velvet box on top.

I tossed it back, but it fell inches short. I was still weak. “Take it,” I said. “Return it.”

He picked up the box and stood, wiping it off on his jeans. I noticed that they were torn at both knees. He held it out to me again, his heart, on his palm. “I got it for you.”

Because he implied I was lovable, because he had bought me a ring, he thought I would absolve him not just for today but for all the times we’d been in danger but too far gone to realize it. And he thought that if we came out of this engaged, we would truly be all right.

I would not take the box. I said, “You need the money.”

“I’ll throw it away.” He raised his fist as if to hurl it right then.

“That’s your decision.”

“I’ll spend it on — ”

“I don’t care.” I really didn’t. Except that I wanted him to spend it all and be ruined too. I wanted him to fail.

I said, “It is not my job to rescue you.”

Luke drew his hand back to throw the ring, probably at me. Neither one of us was lovable now.

Just then, the Kemals pushed the door open. They had heard our voices raised; they had seen the shadow of Luke’s fist through the plastic panel. “No, no,” they said. “Not the lady, not the miss. You go now.”

They meant both of us. Both of us should go. One of them took Luke outside and the other one carried my backpack to the bus stop.

My Kemal and I waited in silence until a bus came. I think he was the father. He hoisted my bag into the bus’s underbelly and we bowed to each other, curt and without touching. I climbed in, and the bus groaned, and I was on my way, past the riddled hills.

It had been a whirlwind. And I thought, Whatever we know will blow away: up to the sky, to the moon and stars. But it will not happen soon. Not soon enough to stop breaking our hearts.

The red profile on the Hill of Dreams grew smaller and smaller, till it was swallowed up in the sky and I didn’t care to watch anymore. And that was it; that was Göreme, that was Luke and me.

Featured image by Mehmet Turgut Kirkgoz on Unsplash

Heavy Petting

Pity and I were smoking with a pair of sixth graders near the school’s lunch dumpsters when the gulls swooped in. We watched the birds pull at the spaghetti that streamed down the rims, remembering how the lunch ladies would fill up the bins each week with uneaten angel hair or fettuccine, how the flocks would dive in for the fresh stuff not ten minutes after.

“Lookit the seagulls!” one of the kids said. When he clapped, the ash on his Newport fell off in a clump.

“Don’t say ‘seagulls’,” I told him. “We live upstate. You see a sea around here? No? Call them ‘ring-billed gulls,’ then, if you want to get fucking technical. Common as head lice up here.”

“You shouldn’t cuss, Mr. Fitz,” said the kid’s friend, scratching his head. He had orange hair, not red. Orange. Bright as Bozo’s.

“This here is an employee smoke break, kiddo,” I said, laying a hand on Pity’s shoulder. “Mr. Fitz gets fifteen minutes of cancer every three hours, no teaching required. Government mandate.”

Pity piped in: “And fifteen minutes of quiet.”

“But those are seagulls,” Bozo started, and then, “Ow!” Because that’s when Pity zinged his lit joint at the kid’s left cheek. Principal Coach and the school’s steroidal Vice Principals didn’t mind our janitor’s pot stash so long as Pity was the one plunging toilets. Deadly aim, that Pity.

“I said ‘quiet’!” yelled Pity, not quiet at all. So the sixth graders trudged back over to recess in a huff. They’d return with their Newports tomorrow, and everything would be just fine again.

“Now that amateur hour’s over,” Pity said, “we’ve got demands to discuss.”

“Demands?” I said. I thought of my ex-wife, Jan Allen, and her girlfriend, Belinda. I thought of the legal envelope and the unsigned closing contract they’d dropped off with me again on Monday. I’d had enough of demands for the week. “Like what?”

Pity rolled another joint, took a small list out of his shirtsleeve pocket.

“West exit by the band room needs a fire extinguisher,” he started. “I can carve out a chunk in the brickwork there, but it ain’t up to code otherwise.”

“Easy peasy,” I said. I dreamed of calling the fire marshal if Coach didn’t comply. Red lights and helmets and the wrath of the local hook & ladder on him and everything. “What else?”

“Eighth-grade French needs a Blu-ray player,” he continued, “and Seventh-grade Geography needs an atlas of Europe with no East or West Germany on it. Just Germany. A big one.”

With Pity, it was never “Mademoiselle Flaneur” or “Mr. Grigsby.” Just the faculty’s grades and subjects. Pity could turn anything into ceremony.

“It’d be no more than fifty bucks,” Pity explained. He shot out five fingers on his left hand like he was learning to count. “Coach could go for that, no problem.”

“It’ll be eighty minimum,” I told him, our free period almost over. “We’ll have to go through central purchasing for it. Gotta find the lowest bid and all that.”

Pity shook both hands this time, ten fingers flying now. “Hell, boy, you know damn well Wal-Mart’s got the lowest bid. How come we can’t ever just buy from the supercenter?”

“It’s all invoices and budgets,” I said. I left it at that because sometimes I had to. “You done?”

Pity took another puff, and I waved the smoke away. “One more thing,” he said.

“Let’s have it.”

A gull landed on one of the bins next to us. I’d never seen one fish out and eat a meatball before, but here we were.

“You missed it at the meeting last week, but we got to talking,” he started. The meatball the gull had picked up was swallowed and out of sight now. But it bulged in the bird’s throat now and didn’t move.

“Spit it out,” I said.

In front of Pity and me, the gull started to dance and panic. It was choking on its spongy find.

“You talking to me or the bird?” Pity asked.

We watched the gull crank its neck up and down as it tried to dislodge the meat.

“You,” I said, still watching the thing thrash.

“No more Thursday night football,” Pity said. “Please.” He kicked the words out of his mouth like he was confessing to something terrible. “School spirit be damned.”

In front of us, the gull hit its head on the rim of the dumpster. It clanged back and forth on the edge, hard, but the ball in the middle of its neck stayed stuck.

“This something you all want?” I said.

Pity stepped in front of me. Made eye contact and looked all business.

“We took a vote,” he said. Held me by both shoulders like we were slow dancing. A foxtrot or a soft waltz, maybe. Like something Jan Allen and I might have done once.

Behind us, the bird started hitting its head on the plastic lid. In the cafeteria somewhere was a poster showing how to perform the Heimlich maneuver.

“Unanimous decision,” he pleaded.

I couldn’t see the bird as it fell. Pity was blocking my line of sight, and I wondered if he’d leave a burn mark on my shirtsleeve. But I heard the thing hit the pavement. A soft whump, and then we both turned to confirm something horrible or natural had happened.

“Okay, then,” I said. The gull’s one exposed eye stared up at nothing and at everything. Above us, a flock of white birds — his friends, maybe? — circled and made plans for noodles and half-eaten bread rolls. “I’ll let him know.”

On my parade to the Vice Principals’ rumpus rooms and Principle Coach’s leather-lined office, I thought of the frozen faculty bodies on Thursday nights and got angry. I thought of us standing in the cold, soda-streaked bleachers for two hours each week, cheering on every pissant play the JV squad ran. Five-yard interceptions from the QB to the other team. Views of the ball flying backwards behind the kicker. Hugs and tears alike in every huddle.

But these sad memories were fuel for me on the walk down. Drums before a skirmish. An application of warpaint. I carried a banner I’d found in front of me: a great triangle of sequined black and gold, our school colors. I was ready.

I could smell the Vice Principals’ jawlines before I could see their office block. Every day a fresh shave, every staff meeting an attack of mid-shelf cologne. Underbites on each of them that had never been fixed. Waxed forearms with popped veins that would’ve made the front office staff gaga if they all hadn’t been terrified of Coach’s personal defense line.

“Help you, Fitz?” one of them asked. ‘Russell’ or something just as baritone. The blondest and newest of the trio, trained to be a junkyard dog like the other two. But we called him ‘Eight’ since he patrolled that grade’s wing.

“Here to see Coach,” I said, unfurling my flag. I presented it to Eight with purpose and meaning and lies in my heart. “It’s important.”

I’d beelined over to the Principals’ office after chancing on a pair of randy high schoolers who’d come down on the bus from the hilltop campus. Before I turned the hose on them, I’d caught them fingering each other in front of Mrs. Trapp’s Art studio, and they’d scared the Color Guard on their way out to practice. One of the girls on the squad had dropped her black and gold banner, and I’d brought it with me now like a winged herald of glad tidings.

Eight latched onto the flag pole like a new toy, and I pivoted around the cloth in an underarm turn and into the first corner of the hallway before he could recover.

It was like dancing with Jan Allen. Made me sad to think of cha chas and rhumbas and box steps we’d never finish. I thought of her girlfriend, Belinda, who would never dip her as well as I might.

Six popped out of his hovel on the left as I entered, barricading the way forward, saying, “Can’t rightly say if Coach is in now, Mr. Fitz.”

“Not looking for him,” I said, pushing ahead. I was mustering up my best crazy eyes, like Jan Allen had made in the days before she got fed up with me and left. “It’s you, Six. Just you.” A feathered wedge of brunet bangs hung down over his brow, and I held him by his bricked shoulders. “You’re wanted out by the bus stop. Those high schoolers are back on their frotteurism again, and I need you to be our man on it. So are you on it?”

The light changed in Six’s eyes as he mumbled out “goddamnitwaithere,” and then sprinted down the hallway with Eight to defend our school against the heaviest of heavy petting.

And there I was: alone now in the paneled hallway of particle-board wood and yellowing class photos, right up until Seven’s door creaked open. I could hear his wood-bead bracelets clacking before he could step into the hall and block my way.

“Whatever you’ve got, Mr. Fitz, it can wait,” Seven said. He’d spread his knotted arms in front of him and above me, a bodybuilder in a bear pose. “Coach is due up in the field house for last period. Laps today. Maybe sprints. Totally important.”

Seven’s hair was black as a goth kid’s diary. It spiked out of the sides of his head in cartoon haystacks of pomade and determination.

“Totally,” I nodded, getting in close. I made like I wanted to lambada with Seven, which gave us both certain kinds of feelings — new, important feelings — but then I rapped my knuckles on Coach’s cheap particle-wood door behind him at the last second.

Seven’s wax-candled face tapered into a snarl the second we both heard Coach bark out, “Door’s open!”

“Don’t mind me,” I said, patting his deltoids. Seven growled, good dog that he was, but I couldn’t stick around to give compliments. I had plans.

Sunlight streamed in through the window that looked out over the west lawn of Klaus W. Tripeltrübel middle school. Dust motes drifted in the air, making the halo effect on the man all the more pronounced.

“Color me impressed, Fitz.”

In his glory, Principal Coach was a protagonist of a man, with a handlebar mustache and a close-cropped mohawk, everything below the neck the build of a ex-college football star, trapped now in fitted khakis and a gingham tie. Wild rumors flitted down from the administration claiming he’d once QB’d for Syracuse, tore through an M.Ed. program after an injury, and then married his cheerleader girlfriend after a pregnancy scare that turned into an actual pregnancy once they put their backs into it. Their American dream was the most American of all the American dreams.

“I thought for certain I was scheduled to cover final period again, but here you are.”

“Here I am,” I said. “Barely. Seven almost stopped me. Good defense on that one.”

Coach looked past me and into the bare hallway, empty now of VPs.

“Not good enough,” he said, touching the college ring on his finger. Like his wedding ring, the jewelry burrowed into his knuckles like it was practicing autoerotic asphyxiation. I daydreamed of something gangrenous happening. “You’ve got three minutes to tell me what you need before I cut for the gym,” he said. “Can’t be late or the kids’ll think they’ve run off another substitute.”

Two weeks ago, Mr. Connolly — who taught the “Career Explorations” class in the mornings, Phys Ed in the afternoons — had been caught high on ketamine he’d scrounged from who knows where. In his best impression of leadership, Principal Coach had driven Connolly to the local rehab and had taken over the last period of the day from the man, forcing the students to run laps since he didn’t know what else to do with them if it didn’t involve line formations and pass plays.

“Heaven forbid,” I said. Coach’s ass cheeks rested on the lip of his desk. I watched him bob up and down as he flexed and relaxed his glutes. “Now I know you’re a busy man, and I won’t julienne words. The union just needs you to sign off on two little things and one big thing.”

Principal Coach smirked. “Bearer of bad news from the Local #1135, are you?”

“It’s the job,” I said. I was unflappable. “Item number one: we need a fire extinguisher next to the band room’s interior doors. It’s going to require a cut into the stonework if you want it to match the set.” And then I shut the hell up.

First one to talk in a negotiation has lost, I remembered someone once saying. When Jan Allen told me she was leaving, I’d talked first and asked why.

“Since this isn’t a fine china pattern, you go and tell Pity,” Coach began, eyes closed now, “to pony out and grab a metal-and-glass box rig, punch a couple of heavy mollies into the wall, and then hang the new extinguisher up. No need to make anyone suck in aerosolized brick.”

“Done,” I said, surprised. Unlike Jan Allen’s revelation about whom and what she loved, this was going well. “Item number two: we need $100 for the French and Geography classrooms. I could get it out of petty cash right now and have everything set up in an hour.”

“Slow down there, Fitz,” Coach said. “Devil’s in the details. What are we talking about here?”

I puffed out my cheeks. I was ready to hoot, throw feces, make war. “A Blu-ray player for French, a new map for Geography. I could rig it up before they came back in the morning.”

Our Principal took his time on this one. Leaned his head back, gave pause.

“Buy the map for Mr. Grigsby. Get Pity on the installation.”

Dust motes ripped around the room in whorls and waves, dancing and falling.

“And Mademoiselle Flaneur needs?” he continued.

“A Blu-ray player.”

“Take the business card, but make certain the thing can play DVDs, too,” he said. “Bring back the receipt or I’ll turn campus into a smoke-free zone.”

The very idea. I was two for two, though, so my hackles were down.

“That’s fair,” I said. “Ready for the big ask?”

“Shoot,” Coach said, reloading his crossed arms like they were empty.

“Thursday nights,” I said, ready-steady, “are henceforth optional, not mandatory.”

I was expecting thunder and lightning. Something painful and loud.

Coach sniffed, “You go to hell.”

So here was the firmament, the levee unbroken. The cessation of chewed gum and bouncing buttocks.

“I knew you were going to hate it,” I said. “But you’re a reasonable man. You know forcing the teachers and staff to show up to the night games isn’t right. On top of that, it’s unfair.”

Our Principal’s posture stiffened, and I knew right then I’d lost. Our dance was over.

“Unfair?” He said it back to me. “Unfair? Well, that may be true. But what it is is contractually obligated. Page seventeen in your employee handbooks, if memory serves — and it assuredly does serve — and what it is is a show of loyalty to our students. And what it is is a sacrifice. A necessary one at that.”

He paused, lifted one cheek to fart, started chewing his gum again and grunted. Flatulence wafted in the air between us.

“Listen here: if I can sacrifice my afternoons to fill in because Mr. Connolly’s drying out down the road,” Coach continued, “then you all can sure as shit show up for an hour once a week to support the squad. You hear me?”

And then the desk bouncing started again, and so did Coach, and then the scent of the man’s gases was gone. Somewhere in the room, an alarm was vibrating.

“That’s time,” he said, arms uncrossing now. He moved to the door and grabbed a whistle off the coat peg. “See your sweet asses in the bleachers come Thursday night.”

Home was a Cape Cod the color of a fresh bruise in the middle of ivy-choked Tudors. Jan Allen and I had purchased it back in the ’90s, sometime right after grunge and flannel. Our realtor was a spiteful widower, angry and bitter now that flipping property had become a younger person’s game. Told us we should buy the place because it’d be a middle finger to the socialites who lived around us.

“This used to be the community gardener’s home,” he explained, tapping his cigar ash onto the living room carpet. “Back when this hellscape was a damn community.”

Jan Allen and I made an offer on the house that same afternoon. On the day we closed, she pocketed the keys, I shaved in the bathroom sink, and we lindy-hopped until we crashed into the hearth. After an ice pack and some takeout Chinese, we rode each other on the berber carpeting until we were dehydrated. I would’ve thought we were happy back then. Might’ve just been the low interest rates.

After making nice with Coach in his departure from the office and then beelining toward my driveway, Jan Allen was there, crouched on the stoop. Next to her was the girlfriend, Belinda, who held her arm like they were conjoined. The pair of them rose from their squat when I slowed and pulled into the drive, and I saw them as they would be seen: Belinda, short and feral, ropey with muscle from working at the kennels, and Jan Allen, tall as a motherfucker, which she was now. Or she always had been.

“Jan Allen,” I said. “Belinda.” In the old westerns I liked to watch, cowboys greeted each other with names and nods, not pleasantries.

“Good to see you, Fitz,” Jan Allen said. My surname was her pet name for me. Until a year ago, the name had been hers, too, right up until it wasn’t anymore.

“Good to see you, too,” I lied. We both lied. It was the same now as waving ‘hello.’

There was a pause in the air as pregnant as we’d never been. Next to my ex-wife, Belinda stared me down, unblinking, the white of a sharpened canine in her snarl for me to see.

“I know I asked this last week, but is there any chance you’re ready to close?” Jan Allen asked. “We won’t have a buyer much longer if you keep doing this.”

“No?” I said. There would be a cigarette in my hands if I could just make them leave.

“Then like I said last week: go fuck yourself,” she said, gutting past me toward the rig. Belinda loped right in step with her, growling and looking tired and angry and fierce. I’d never smelled venom before, but the stink of hatred on her was something awful. “Let me know if you ever want to stop paying your half of the mortgage, you idiot.”

While I still had the old homestead, Jan Allen still drove our black truck, with the big payload neither of us would ever need. In the moment she and Belinda knifed past me, I watched as the girlfriend sprinted for the passenger seat, leaping up into it so she could keep hold of her hex on me, or whatever she was cooking. But Jan Allen climbed up behind the steering wheel like she was mounting a Clydesdale, and I remembered that we’d once been in love.

“I saw a bird die today,” I yelled to her. It was tough to get her attention over the V12 diesel, but I pressed on. “It was there one minute, funneling pasta, and then it wasn’t.”

“What?” she yelled, her window down.

“And I saw two teenagers with their hands in each other’s pants,” I yelled back.

Jan Allen killed the engine just then, squinting at me from behind her wraparounds. She and gun enthusiasts wore the same eye protection.

“What?” she yelled. “Goddamn it, what are you saying?”

And I missed this house, I wanted to tell her. I missed us.

“It’s been a bit of a day!” I yelled back. “I’ve changed my mind?”

Jan Allen and Belinda murmured under the rip of the engine. I saw teeth and consolations, saw promises being made. But then the driver’s side door opened, and my ex-wife led me into our old home in a perp’s escort. Strong arms, my old flame.

“This better not be a trick,” she said. “We’ve got a pot of fettuccine Alfredo waiting for us back home, goddamn it.”

I thought of Jan Allen and Belinda mixing cream and parmesan cheese in a saucepan until it blended together. Of cracking pepper over hot, flaccid noodles.

“If you’re serious, initial here,” she said inside the door, closing papers appearing from her vest. “And sign here.” Our hands touched at the knuckles. It was the most action I’d had in months. “And here.”

“Are you happy?” I asked, wondering if she smelled old smoke in the house. If she did, we’d have to pay for the cleaning. “With her?”

“I will be,” Jan Allen said, flipping the paper over. Our realtor’s card was at the bottom of the page, his photo embossed above the name. Red polo shirt, forearms big as Belinda’s. “Sign and date here.”

So I did. I watched Jan Allen force all the air out of her lungs. She flipped the water faucet on and off again. Like she was checking on the condition of the place.

“Gotta say, Fitz,” she said, “this feels good. Long time coming, you know?”

“I know,” I said, wondering why I gave up everything I loved without a fight. “I’m sorry.”

And my ex said, “What made you change your mind?”

“If I’m being honest,” I told her — and I wasn’t being honest — “it’s work. It’s Pity and the admins and the other faculty. They look up to me now. Like I’m their defense against Coach and the VPs. It’s a leadership thing, babe.” I watched her flinch at the old pet name. “As above, so below, you know?”

“Not really,” she said, shaking her head. Her mouth hung open, and I loved her for it.

“Do you remember dancing with me?” I asked. “Like we did that first night?”

I watched Jan Allen pick up the contract and shuffle the papers together.

“We had a good thing there for a while,” she told me, smiling. “But you know that’s over now, right? I’m not that person anymore.”

“I know,” I said. Outside, Belinda was honking the horn. One beep, two. Foot revving hard onto the accelerator for effect. A wild scream of “Let’s go!” sent out from the open window and into the neighborhood.

“Well, that’s me,” Jan Allen said, leaning toward the door. She was almost to the foyer, to the front closet that hid nothing but pipes and galoshes now. “Look, Fitz, once we close and you move out, you should start over. Maybe find someone new. Someone who likes dancing, you know?”

I used to dream of Jan Allen and I celebrating our 80th birthdays with cake and passion. We’d travel on cruise ships to Canada because that’s what people our age would do. We’d die within hours of each other — maybe from a gas leak — and our surviving pets would eat our unmoving flesh because they wouldn’t receive nourishment otherwise, maybe starting with our faces because that’s what they loved best. We’d love them back, though, and buy them premium kibble until the end.

“I ought to,” I said. “Sure I will. I’ll do that.”

Then Jan Allen got that look in her eye like maybe she believed me, maybe she didn’t. Like everything else I’d loved in my life, I’d given this away, too. But she nodded just the same, said nothing, then hiked back to the truck. As she revved away, I watched Belinda knife an imaginary line across her neck at me. I read it more as a note of separation from her and her lover, an end to things, less so a threat of death and great pain, and then I called Principal Coach because I knew what Belinda had meant.

The boys’ early practice was just finishing up as I kludged into work the next morning. I watched the football team stream down the hill after their laps, several of them puking into the grass and making yellow puddles of eggs or chewing tobacco, maybe both. Behind them, Six, Seven, and Eight rustled them down through the grass like cattle, and, overhead, I swore I could hear the gulls making hungry sounds and smacking their beaks in anticipation. They had the foul appetites of dogs sometimes, and I worried about the future.

“Glorious thing to see, Fitz,” said Principal Coach. He wore a black and yellow polo with a chaw packet bulge in his gums. Below us, the VPs wore the same dark shirts and bulges as Coach, like myna birds in the mating season.

As above, so below, I thought.

Coach continued, “To see these young men being whittled into war engines, you know?”

I didn’t. “Got a second?”

“I will,” Coach said. Then to the boys: “Shower up, dress out, and if I hear about your stench from anyone in first period, we’ll do burpees until you deflate. Understood?”

And then the Greek chorus of vomit-fresh voices: “Yes, Coach, sir!” Below me, adolescents rolled down the hill in waves, bile and hope on their lips, and the VPs clapped in time.

“Now what can I do for you, Fitz?” Coach asked.

I paused. Gathered courage from the ether. “I come bearing gifts,” I said.

“That right?”

“You hate teaching general Phys Ed in the afternoons,” I said, “the students hate taking it from you, and you’re pissed you can’t make them run drills like they’re your second string.”

“Watch your tone, Fitz.” Around us, the ground was soaking up the ovals of vomit and chaw.

“But I can do it,” I said. “I can take Connolly’s class off your hands.”

Coach laughed then, but he still rubbed his scalp with both hands as though he were honestly thinking about it.

“What would you teach?” he asked. “Because you didn’t letter in a damn thing in high school.”

“Dance,” I said, unfazed. “Ballroom. Swing. Not so much modern or ballet, but you know I’d get their growing hearts pumping.”

“But — ” Coach started.

“What I don’t know,” I interrupted, “I can learn and then teach the basics. I’ve played some ball, served some volleys. I’ve tagged schoolchildren with dodgeballs, and I’ve drawn blood. But this way, with dance, maybe I’d at least give them something I’m good at.”

Coach’s rubbing intensified. The folds of his neck, the bristles of his mohawk, the stubble below his mustache.

“So what I get is a free period in exchange for the faculty getting out from Thursday night games?” he said. “Is that it?”

“That’s the proposal, I reckon.”

“You reckon.”

Scalp to earlobes, earlobes back to scalp, scalp down to bridge of his nose in a slide of thick fingers.

“You’ll all be there for Homecoming, though,” he whispered, “and every game during the playoffs, if we ever make them again. Every single one. You hear me?”

“I hear you,” I said. “We hear you.”

Coach looked out over the fields then, and I followed his gaze. Gulls flew overhead and sought out trash. In my future, I saw the shakes of nicotine-free afternoons hereafter, the sweat of young frames on freshly waxed gym floors.

“For you,” Mr. Grigsby said, slipping a blue Swingline into my hands. He touched my shirtsleeve, rubbed it like a St. Christopher’s medal, and I watched him kowtow away.

Around us on the Tripeltrübel gym floor that Thursday, the least athletic of the eighth graders waltzed in uneven boxes. They stumbled over shoelaces that weren’t there, groped asses by mistake or on purpose, blushing either way.

Next came Mademoiselle Flaneur. “For you,” she said, nestling a Toblerone into my briefcase. She bowed as she left, and I nodded my benediction. The chocolate would be gone before final bell.

“Been like this all day, has it?” asked Pity, slipping in silently. “You and the flock?”

In the far corner, a blond waif of a boy slipped and fell while spinning his partner. The girl sighed, kept dancing to the 3/4 time signature I’d piped in overhead. Another girl from the bleachers swept in to take the boy’s place, to lead, but we could all tell who was twirling whom.

I nodded. “Gifts to staunch a wound after falling on a sword, I suppose.”

“What’d you say to Coach?” Pity asked.

“Nothing much,” I said. “Just made a trade, fair and square.”

Last in line was Mrs. Trapp, her fingers smudged with pastels. Today was an advanced session of nude figure drawing, and, judging from her state of undress, she’d served as both their instructor and their model.

“I made you a little something, Fitz,” she murmured, placing something in my hands. I felt the rough fabric of a cross stitch in a hoop, set in a balsam oval. “It’s nothing, really, but thank you.”

We watched Mrs. Trapp straighten and march through the center of the gym, head high between the whirling dervishes of tweens and teens, then out the door toward not a scheduled football game but somewhere else. A home, maybe. Hers.

Pity said quietly, “Lookit,” and I did.

There, in my hands, Mrs. Trapp had laid a pattern sewn to look like our school mascot, the Tripeltrübel Troll, outlined in black and gold, its hands dripping red arterial blood and holding a person’s severed and mustachioed head, possibly Coach’s. I couldn’t tell, really.

“Now that’s damn pretty,” breathed Pity.

“No, sir, it’s ugly as sin,” I told him. “But it’s yours if you want it.”

Featured image: Shutterstock/Ola Koval

A Summons to England

Even in business class, with an empty seat beside her, Becca couldn’t sleep. She turned on the overhead light and read the conference materials, Tort Law in Transition, 1982-1992: A Transatlantic Perspective.

She hadn’t wanted to go to London. She knew she should be chuffed, as Liam would put it, being asked to stand in for a senior partner and speak about American class actions. It was March 1992; the partner’s typed notes rambled on about patients suing the manufacturer of faulty heart valves; female coal miners alleging harassment; Vietnam vets suing Dow Chemical for diseases from Agent Orange. Becca had little experience with class actions; she suspected she was asked because she spent her first six months assigned to the firm’s London office. A coveted gig, that one, too, even if in reality it was a glorified document review. It changed her life forever. While living there, she met Liam, at the London Apprentice Pub in Isleworth.

“Didn’t I hear you have an English husband?” the partner asked when he showed up in her office Friday afternoon. “He can go too, if you like. You’d only have to pay his airfare.”

Becca said her husband couldn’t miss work. The partner stared at the only picture on her wall — a Hogarth reproduction: a bewigged barrister on a throne, scrawny clerks scrivening below, scales of justice lurking in a corner. The partner was looking for a wedding picture or at least a photo of Becca and Liam engaged in some sport, standard décor for recently-married lawyers. But there was no photo of Liam, or of Becca either, only an empty space on the wall above her desk, where a picture-hook remained.

The partner didn’t know that Becca’s English husband had left her. None of the lawyers and staff with whom she worked knew. Nor did her mother, who had moved to Florida and barely knew Liam. Nor her best friend from law school, who lived in Chicago and worked crazy hours, like Becca.

Later than she should have, Becca realized Liam wasn’t coming back. After Liam had been gone two weeks, it was her birthday. She thought she’d hear from him. When Becca’s mother called from Florida, she was all excited about the play her drama club was doing, Moor Born, about the Brontes. She was playing Anne, the least famous, least creative sister; nonetheless, the competition had been fierce. “By the way,” she asked, “what did Liam get you for your birthday?”

“It’s a surprise,” Becca said. “For tonight.” Her mother asked her to report back. Becca knew she wouldn’t ask again unless Becca brought it up.

Nine months later, the opportunity to tell someone — anyone — was gone.

Liam left in June, at the end of his second year teaching science at Manhattan Prep in Yorkville. He said he needed time to himself after the intense push of proctoring, grading, and graduation. He’d gone off this way before, beginning when they lived in Isleworth. He always returned the next day, or the day after.

This time, days became weeks; weeks became months. She wondered if he had returned to London. His passport was missing. But if so, where would she begin to look for him? With his cousin Saul? The two didn’t get along. Becca and Saul were more simpatico than Liam and Saul had ever been. Their six months in London now seemed a dream, fleeting and unreal. Liam had introduced her to only one friend, a struggling actor named Trevor Thorn, who was heading to Australia to appear in an independent film. There were Aunt Lillian and Aunt Rachel, both around 80, older sisters of Liam’s father, who died of a heart attack at 65. Liam referred to his spinster aunts and his cousin Saul as “the Jewish side of the family”; stuck in the Old World, he said, even though born in Leeds. The aunts had lived together for decades in a small flat in North London. When Liam learned that Becca was Jewish, he said, “I have some people I’d like you to meet.” Soon afterwards, he took her to visit the aunts. It was as if his Jewish lineage, for once in his life, enhanced his standing.

Several times after that first visit she went to see the aunts on her own. During her time in London, they were exceptionally kind to her. Aunt Lillian, with her erect posture and stark white cap of hair, her take-charge voice, grasped Becca’s hands to welcome her to their flat. Aunt Rachel was softer, rounder, her gaze transparent and direct. She listened intently to Becca, nodding encouragement, as if she knew what Becca was going to say before she said it.

Then, on a Saturday when Liam was gone, Becca ran a fever. She tried to reach the London office manager, but couldn’t. Her heart and head pounded; the room spun. She phoned the aunts. Eventually a knock. Aunt Lillian directed the driver to a North London clinic, near the aunts’ flat. A nurse wheeled Becca into a room so white she had to close her eyes. Someone undressed her and put her in a hospital gown, hooked her up to an IV, although Becca had no memory of any of this.

Becca woke in the North London hospital and there they were: Lillian in a chair, Rachel fussing with a tray. The smell wasn’t the normal hospital smell. “The sweetness of the soup,” Aunt Rachel had explained one Friday evening, “is from parsnips. On Fridays the grocer saves some for me.” Rachel settled on the side of the bed and brought a spoon to Becca’s lips. “Warm,” she said. “Not scalding.” Becca didn’t know how long she’d been in hospital, how long the aunts had been there. She wondered where Liam was.

That time, he came home the next day.