Review: Aline – Movies for the Rest of Us with Bill Newcott

Aline

⭐⭐⭐⭐

Rating: PG-13

Run Time: 2 hours 13 minutes

Stars: Valérie Lemercier, Sylvain Marcel

Writer/Director: Valérie Lemercier

There are so many reasons why Aline—a barely disguised cinematic biography of Canadian supersongstress Celine Dion—has no right to succeed.

Written and directed by its star, French comedian Valérie Lemercier, the film’s over-the-top evocation of the singer’s humble beginnings, early professional struggles and ultimate unhappy success seems to lampoon the traditional tropes of show biz bios. More outlandishly, Lemercier, now 58, even plays 12-year-old Aline—the actor’s face digitally superimposed on the body of a young girl with no apparent effort to disguise the effects of age.

It’s all goofily absurd, yet the whole film is played absolutely straight, with earnest performances by all and an evocative music score that relentlessly telegraphs how the audience should be feeling at any given moment.

What’s more, it’s even a stretch to say the biographical elements of Aline are “disguised” at all: The opening credits brazenly declare the whole film is “inspired by the life of Celine Dion.” Aside from some judiciously placed classic pop numbers, every song is a Celine original, voiced by a French sound-alike singer named Victoria Sio.

Random cinematic absurdity has never appealed to me, and I’m not much of a Celine fan. So, why did I sit at rapt attention through every second of Aline’s two-hour-plus run time?

For one thing, the absurdities of Aline are perhaps not quite as random as they seem, in that Dion’s real life seems to have consisted of one absurdity after another. Celine really was the youngest of 14 children, raised by working parents in Quebec. She really was discovered at age 12 by a talent agent after her brother sent him a cassette tape in the mail. And she really did eventually fall in love with and marry the guy, even though he was 30 years her senior.

As screenwriter, Lemercier has gifted herself with the role of a lifetime; an ageless character who dwells somewhere between Judy Garland in A Star is Born and Audrey Tatou in Amalie. Playing Alina’s much-older husband, Canadian actor Sylvain Marcel (who is actually the same age as his leading lady) sketches the man with endearing, wide-eyed charm. This is a guy utterly without guile; his love for Alina is as pure and clear as her chime-like voice. In a film where the most credibility-stretching twist is the love of a vivacious teenager for a middle-aged show biz schlump, Marcel makes that conceit not just believable, but somehow inevitable.

There may be legal reasons why Lemercier plays the biography/not really a biography card so coyly (Dion has pointedly refused to comment on this unauthorized sort-of adaptation of her life). In the end, though, even as Alina mostly traces its subject’s life story with the slavish faithfulness of a Wikipedia page, what emerges is something more nuanced than your garden variety screen biography.

Even in their most “realistic” representations of life, Lemercier reminds us, movies are no more authentic than an oil painting. Filmmakers choose the palette. They enlist the models who stand in for the subjects. They even dictate the angles from which we view the subject, controlling our perspective and, in a very real sense, controlling our judgment and emotion.

Lemercier is not the first French filmmaker to make it a point to remind the audience, over and over, that “it’s only a movie.” Jean-Luc Goddard, now 91, has been doing that since the Sixties. But seldom has a director been so jovially good-natured in the pursuit; so happy to let us see the director’s hand with such happy results.

Featured image: Scene from Aline (Roadside Attractions and Samuel Goldwyn Films)

Farewell to a King: Chadwick Boseman Dies at 43

It’s a cliché to say that you don’t have the words, but some clichés became exactly that because they’re true. As the word raced across internet Friday night, two things were certain: people were stunned, and the celebrated actor Chadwick Boseman was dead at age 43 after a four-year struggle with colon cancer. It’s hard to articulate why Boseman meant so much to so many people in such a short time, but that makes it no less true. Whether playing Supreme Court Justices or glass-ceiling-shattering baseball legends or the Godfather of Soul or the Avenger King of Wakanda, Chadwick Boseman entertained, inspired, and did his level best to make the world better.

Chadwick Boseman Tribute to Denzel Washington (Uploaded to YouTube by TNT)

Chadwick Boseman graduated from high school in South Carolina in 1995; he’d already written his first play as a junior. He headed to Howard University, and earned a Bachelor of Fine Arts in Directing. Among his teachers was Phylicia Rashād; in a story that’s now part of Hollywood lore, Rashād reached out to other Black actors to find financial support to send Boseman and others to the Oxford Mid-Summer Program of the British American Drama Academy in London. Boseman discovered that the person who was responsible for his own trip getting funded was Denzel Washington. In 2019, Boseman had the chance to thank Washington publicly at the AFL Life Achievement Award event honoring Washington.

The trailer for 42 (Uploaded to YouTube by Movieclips Trailers)

Boseman broke into television in 2003, working on a number of shows, including the NBC dramas Third Watch, ER, and Law & Order. His film debut came in 2008 in The Express: The Ernie Davis Story, in which he played future NFL Hall of Fame halfback Floyd Little. Although he was still writing plays and considering giving up acting altogether so he could direct, he broke through to greater notice with 2013’s 42, in which he played baseball legend and agent of change Jackie Robinson. After that, he essayed another immortal Black American in 2014’s Get on Up; as James Brown, Boseman got most of the film’s critical attention. David Denby of The New Yorker wrote “Chadwick Boseman gives a startling and galvanic performance,” while James Berardinelli of ReelViews wrote “Whatever failings the film may have, none can be laid at the feet of lead actor Chadwick Boseman, whose performance is phenomenal.”

In October of 2014, at a surprise event orchestrated by Marvel Studios to announce their “Phase 3” line-up, Boseman was introduced to wild applause as the actor that would be playing T’Challa, the Black Panther. Robert Downey, Jr. quipped, “Get used to all that applause, by the way.” He wasn’t wrong. Boseman debuted as Black Panther in 2016’s Captain America: Civil War, making a strong impression in a film that was packed with stars (and also introduced Tom Holland’s Spider-Man to the Marvel Cinematic Universe). But that was just preamble to the phenomenon that would ensue when Boseman headed up the Black Panther solo film in 2018.

The Black Panther trailer (Uploaded to YouTube by Marvel Entertainment)

There was something in the air leading up the debut of the film, and it exploded to life on an extraordinary President’s Day weekend when it took in $242 million in just four days. Director Ryan Coogler had made a film built on Afrofuturism and a keen sense of identity that also stayed steeped in Marvel continuity and that brand’s mix of action and humor. The film featured complex moral questions and challenged audiences with a villain (Michael B. Jordan’s Erik Killmonger) that had an understandable motive. Boseman was the gravitational force at its center, struggling with the burden of leadership and the understanding that earlier generations might have made grave mistakes. He acted with regal bearing and purpose, believable as both hero and human. He anchored the film to seven Academy Award nominations, including one for Best Picture, a first for a super-hero film.

Across the Black community, the film itself became something of a celebration; for millions of children, here, finally, was a hero of an order of magnitude that also looked liked them. The movie made over a $1.347 billion; it was even the first film shown in Saudi Arabia after a 30-year theater ban. It was a super-hero movie, but it mattered. It resonated through all levels of culture. The “Wakandan Salute” became commonplace, and Indiana Pacers star Victor Oladipo, with as assist from Boseman, wore a Black Panther mask in the NBA Slam Dunk Contest.

In 2017, Boseman played Thurgood Marshall in the film Marshall, which dramatized one of his early cases, years before he became the first Black Supreme Court Justice. He returned to the role of Black Panther in Avengers: Infinity War in 2018 and Avengers: Endgame in 2019. Endgame wrapped up its run as the biggest moneymaker in box office history. 2020 saw the release of Spike Lee’s Da 5 Bloods, which matched Boseman up with a strong ensemble cast. He had already filmed the as-yet-unreleased Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom, based on the work of August Wilson, and Black Panther 2 had been scheduled for 2022, but had not yet begun production.

However, as Boseman was building his Black Panther character across the MCU, one thing was kept from public view. He had been diagnosed with stage III colon cancer in 2016. Boseman quietly battled it, through what the actor’s Instagram called “countless surgeries and chemotherapy,” for the last four years. The disease progressed to stage IV, and the actor passed on August 28, 2020 “in his home, with his wife and his family by his side.”

Public statements came quickly. Marvel Studios released a statement that began with, “Our hearts are broken.” Fellow Avenger Brie “Captain Marvel” Larson posted “I’m honored to have the memories I have. The conversations, the laughter.” Chris “Captain America” Evans tweeted “Chadwick was special. A true original.” Director Jordan Peele said, “This is a crushing blow.” And literally thousands more.

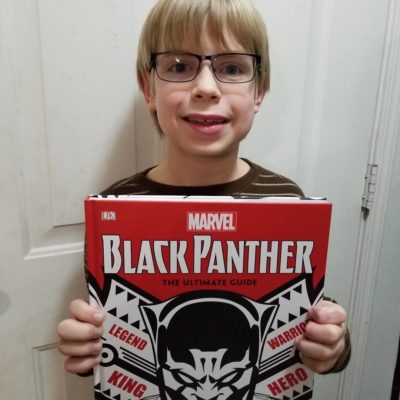

Kyle and his book. (Photo by Troy Brownfield, January 19, 2018).

Chadwick Boseman touched a chord. He struck an electric nerve in the heart of a world that needed reminded that heroes don’t have to look like you. If you’ll allow a personal digression, my youngest son was 11 when Black Panther was released. He and his brother had been Marvel fans basically since birth (it’s a thing that happens in a house where dad writes comic books). He came to me ahead of the movie and told me that he had something he wanted to buy with his own money that he’d been saving. I asked what it was, and he showed me online. It was the DK Publishing Marvel Black Panther: The Ultimate Guide. And I was proud, proud that my little white, blonde-haired, blue-eyed boy saw an awesome hero that he wanted to know more about. Proud that he knew that a hero didn’t have to look like him, even as it was so important to so many that he did. And it wasn’t just that one book; action figures, hoodies, basketball shorts, throw rugs, Funko Pops . . . that kid was and is a legit fan. The boys are asleep as I write this; it’s going to break their hearts to hear it. It breaks mine to write it.

Jack Kirby, who co-created Black Panther with Stan Lee, was born 103 years ago today. A beloved artist, they called him “The King.” It may be fitting that Chadwick Boseman passed on Jack Kirby’s birthday, which is also the anniversary of the 1963 March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, the venue for Martin Luther King, Jr.’s “I Have a Dream” speech. Remarkably, August 28 is also celebrated as Jackie Robinson Day in Major League Baseball. The loss of Chadwick Boseman is a generational loss. Although he had accomplished much by 43, we will forever speculate on his untapped potential. His body of work will continue to inspire, both as a super-hero and as the all-too-human characters that he so frequently played. The Saturday Evening Post extends its condolences to his family, his friends, his colleagues, and his fans. Wakanda Forever.

Featured image: DFree / Shutterstock

Hollywood’s New Maestros: The Rock Stars Who Are Composing Film Scores

The score of a film is unlike a hit song. A movie score is in the background of the action — and usually instrumental. It sets the tone of the film without calling too much attention to itself. Film composers like John Barry, Ennio Morricone, and Henry Mancini made careers for themselves by creating rich soundscapes for cinema of every genre. Comprehensive orchestral training was requisite for composers in Hollywood for many years, but, increasingly, tinseltown has been importing rock and pop musicians to write scores.

There is a history of pop music in movies, but film collaborations from members of Radiohead, Daft Punk, Nine Inch Nails, and Arcade Fire in recent years are blending the mediums like never before. What possesses these rock stars to step out of the spotlight for the more concerted — and sometimes grueling — process of film scoring?

It could be the prospect of artistic growth. Graeme Thomson covered the rise of rock stars in movie music in The Guardian in 2009, venturing, “Although there’s next to no money to be made in writing for film, and all along the line the musician’s vision is subordinate to that of directors, editors and producers, the chance to be a mere cog in a much larger machine seems to offer welcome relief from the essentially solipsistic nature of songwriting.”

Just as a writer desires a prompt, artists of the indie rock world might crave boundaries for their creative instincts. Sometimes the results are groundbreaking.

Trent Reznor won an Oscar for his part in scoring The Social Network in 2010. The lead singer of Nine Inch Nails is known for a gritty brand of heavy rock, but his compositions for films like Gone Girl and The Girl With the Dragon Tattoo are more subdued and electronic.

Jonny Greenwood, lead guitarist of the Grammy-winning band Radiohead, has scored several of offbeat director Paul Thomas Anderson’s films. Greenwood started composing for Anderson in the 2007 film There Will Be Blood. Greenwood’s score is an unsettling and, at times, sparse and dissonant accompaniment to Anderson’s film that the New York Times has called the best film (so far) of the 21st century. Greenwood has scored all of Anderson’s films since: The Master, Inherent Vice, and the forthcoming Phantom Thread.

Reznor and Greenwood have garnered significant acclaim for their efforts, but reactions to musicians in the film industry haven’t always been so positive — particularly from career composers. In the ’90s, highly trained orchestrators bemoaned that film scoring was being taken over by amateurs. Many new to the field were missing out on important musical training due to new technologies that rendered comprehensive craftsmanship unnecessary. “And it’s the absence of those skills that many movie professionals believe is the primary reason for a paucity of good film music now,” lamented David Mermelstein in a 1997 article from the New York Times. In Mermelstein’s article, Jerry Goldsmith, composer of scores for Chinatown and Patton, joined several other Hollywood music greats in denouncing the “preponderance of dilettantes and sophomoric people in the business,” but they felt that real talent would ultimately win the day. Has it?

The popification of film scores can be traced back to the ’60s. Mike Nichols pioneered the mixing of popular music with cinema in 1967 with The Graduate. Nichols used Simon & Garfunkel’s folk tunes as a soundtrack to his coming-of-age film about disillusionment and isolation. This practice was brand new at the time, and it paid off: The Graduate was one of the highest-grossing films of the 1960s.

Afterwards, musicians trickled into the industry. Hans Zimmer was associated with several early new wave bands including The Buggles and Krisma before turning to films. Today he is best known as the prolific scorer of dozens of movies, including Pirates of the Caribbean and The Lion King. Tim Burton collaborator Danny Elfman got his start in Oingo Boingo, the eclectic group behind the songs “Dead Man’s Party” and “Weird Science.” Tunesmith Mark Mothersbaugh started in the cult ’80s group Devo. Mothersbaugh has collaborated with Wes Anderson on Bottle Rocket, Rushmore, and The Royal Tenenbaums in addition to his work in many family movies like Halloweentown, Hotel Transylvania, and Cloudy with a Chance of Meatballs. He has even scored several popular video games, namely in the Crash Bandicoot and Sims series. The ’80s and ’90s pop interlopers mostly left their groups for Hollywood pursuits.

These bandmates-turned-maestros signaled a shift in movie music, but it might not be the end of orchestration as we know it. Jon Burlingame teaches film music history at University of Southern California, and he’s been following Hollywood music trends for years. New music technology continues to give rise to original voices in cinema, and Burlingame believes this is good for the industry. However, he says, “There is an advantage to working with a composer who has a big toolbox. You should never count out the level of experience already in Hollywood.”

Composing a film score is still very different than writing a pop or rock song. According to Burlingame, the film composer’s task includes making music that underscores the emotion or drives the action or provides a musical counterpart to the location or time. He says, “These can be challenging prospects for someone who hasn’t worked in film before. You absolutely have to have a dramatic sense. Sometimes it’s an instinct; sometimes you can learn it.” Whatever that dramatic sense entails, it seems that the rock stars are learning it.

See our recent interview with film composer Hans Zimmer from the November/December issue.

Censorship in American Filmmaking

“There’s too much sex and violence in film!” This is an argument we’re used to hearing today, but did you know this accusation has been levied against Hollywood as early as the 1920s?

In what is commonly referred to as the “pre-code” era, American cinema had no restraints on objectionable content.

But in 1915, the Supreme Court decided that film was not art, because it was meant to generate profit and thus should not be protected by the first amendment.

In the case of Mutual Film Corporation v. Industrial Commission of Ohio, the judges reached a 9-0 decision that “The exhibition of moving pictures is a business, pure and simple, originated and conducted for profit…not to be regarded, nor intended to be regarded by the Ohio Constitution, we think, as part of the press of the country, or as organs of public opinion.”

Realizing that this ruling could mean government oversight of the film industry’s as-yet unregulated operations, the studios moved to head off a federal censorship board. In 1922, they created the Motion Picture Producers and Distributors of America (MPPDA) organization.

William Hays, the former Postmaster General and head of the Republican National Committee, was chosen to lead the organization, a calculated move to provide sway with leaders in Washington. The MPPDA intended to show D.C. politicians that federal censorship wasn’t necessary, as the studios were censoring themselves. Yet through the early 1930s, the MPPDA made little attempt to regulate film.

As the Great Depression started and expendable incomes all but depleted, American filmmakers struggled to fill the seats. To coax the public back the the theaters, filmmakers resorted to increased use of sex, violence, and other not-necessarily-wholesome gimmicks in their movies.

When the MPPDA did nothing to clean up the new sensationalism in cinema, other groups sprang up to take matters into their own hands. State and city censorship boards were already scattered across the country, but they began to flex more power. And then the Catholic Church decided to take action.

Fed up with the lack of censorship in Hollywood, Catholic bishops founded the Catholic Legion of Decency in 1934. Their self-anointed task was to clean up cinema with a three-tiered rating system, and churchgoers across the country were told that all good Catholics must adhere to the standards set forth by the CLD. The ratings: an “A” film was deemed “morally unobjectionable” ; a “B” film was deemed “morally objectionable in part” ; a “C” film was “condemned.”

Negative press from boycotts on some films and the financial losses that followed finally pushed the MPPDA to act. Though a code of decency–often referred to as the Hays Code, named for the head of the organization–had been written in 1930, a loophole in policy had kept the rules from ever being enforced on the film industry. Now, thanks largely to the actions of the Legion of Decency, the years of the MPPDA turning a blind eye had come to an end.

In 1934, the MPPDA established the Production Code Administration (PCA) to be the enforcement arm of the establishment, headed by Joseph Breen.

The code comprised a list of “Do’s” and “Do Not’s” for filmmakers, and any film that didn’t adhere to the standards would be denied an MPPDA stamp by the PCA. Since the studios, all members of the MPPDA, owned the vast majority of theaters at the time, any film without a MPPDA stamp was barred from being shown at almost every theatre in the country.

Thus the MPPDA, the PCA, and the National Legion of Decency (they replaced “Catholic” with “National” in 1934) coexisted harmoniously for decades. A film with a C rating from the NLD was rejected by the PCA, and vice-versa.

Film stars known for their sexuality like Mae West were virtually put out of business, the gangster genre was forever altered, and political and social pressure eased. State censorship boards stopped making changes almost all together. Then everything changed again.

In 1952 the Supreme Court heard yet another case regarding cinema. In the case of Joseph Burstyn, Inc. v. Wilson, the judges ruled that New York could not ban the commercial exhibition of a film because of sacrilegious content, as film was an artistic medium, protected by the 1st amendment.

The decision, more famously known as the “Miracle Decision,” made the 1915 ruling null and void. Films now had teeth to defend themselves individually against federal censorship, but this did not mean the end of the overseeing MPPDA.

By 1945, the new head of the organization, Eric Johnston, rebranded the MPPDA to what is known as today the Motion Picture Association of America (MPAA). With mounting pressure from the industry, the next head of the MPAA, Jack Valenti, did away with the production code in 1968.

Though the threat of Federal censorship had faded away, Hollywood was still wary of boycotts and state and city censorship boards, so Valenti implemented a voluntary rating system to replace the now defunct production code: “G” for “general audiences” ; “M” for “mature audiences” ; “R” for “restricted” ; and “X” for “adults only.” In 1970, “M” was changed to “GP” which meant “all ages admitted, but parental guidance suggested.” This was switched to “PG” in 1972.

At the suggestion of Stephen Spielberg, “PG-13” was introduced in 1984. And finally, when a lack of trademarks led to it being co-opted by the pornography industry, “X” was replaced with “NC-17,” in 1990. Originally, the MPAA provided no reasoning for the ratings of any individual film, but since 1990, a brief explanation has been attached to each rated piece.

To this day, it is the exhibitors who enforce the MPAA policies–there is no federal or state law that bars people who are underage from viewing any film. Instead, the MPAA is left to police its own terms, and producers voluntarily have their films rated (though all 7 major studios and most independent films that get distribution still go through this practice).

Over the years, filmmakers have levied criticisms at the perception that the MPAA has an innate policy of rating independent films more severely than they have rated studio films.

Along with complaints about seemingly arbitrary decisions regarding what can and can’t be shown in an R-rated film versus an NC-17-rated film, South Park creators Matt Stone and Trey Parker have publicly lamented about their contemptuous dealings with the ratings board when working on their independent film, Orgasmo, compared to the relatively easy time they had in dealing with the organization for their studio film, South Park: Bigger, Longer, and Uncut–films with content arguably similar in language, sexual overtones, and adult themes.

In 2004, the MPAA appointed former Senator Christopher Dodd as its new head, maintaining their appointment of leaders with political ties in Washington, largely because the MPAA plays a central role in lobbying for the interests of the film industry. This includes supporting such bills as the “Stop Online Piracy Act,” or “SOPA.” (Since SOPA was defeated, Dodd has urged a more friendly approach to dealing with online entertainment media.)

While the MPAA is still going strong, the same cannot be said for the National Legion of Decency. In 1966, it was rebranded as the National Catholic Office for Motion Pictures.

It then became a part of the United States Catholic Conference, which was then incorporated into the United States Conference of Catholic Bishops in 2001.

The rating newsletter stopped all together. The state and city boards of government censorship began the long process of shutting down in the latter half of the 20th century.