Cartoons: Election Time

Want even more laughs? Subscribe to the magazine for cartoons, art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

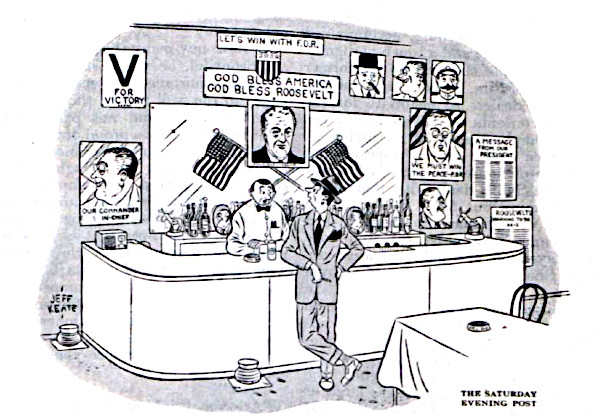

Jeff Keate

October 7, 1944

Bill King

September 13, 1952

Hoff

July 12, 1952

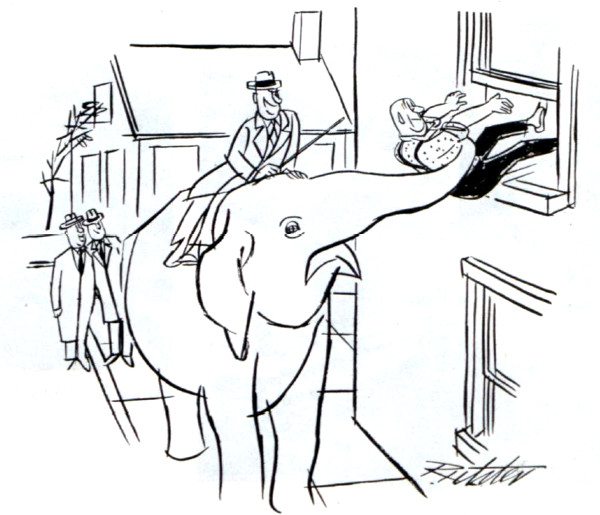

Richter

March 15, 1952

Stan Hunt

December 8, 1951

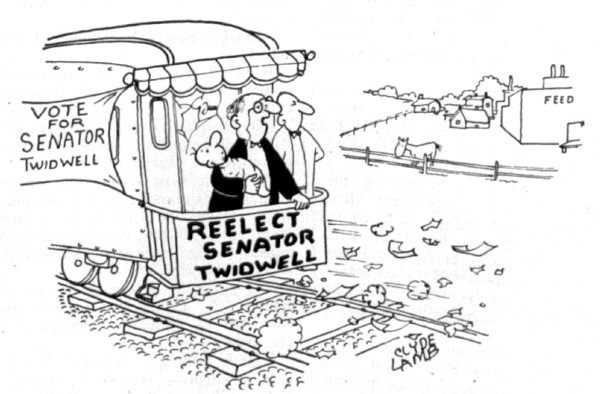

Clyde Lamb

December 1, 1951

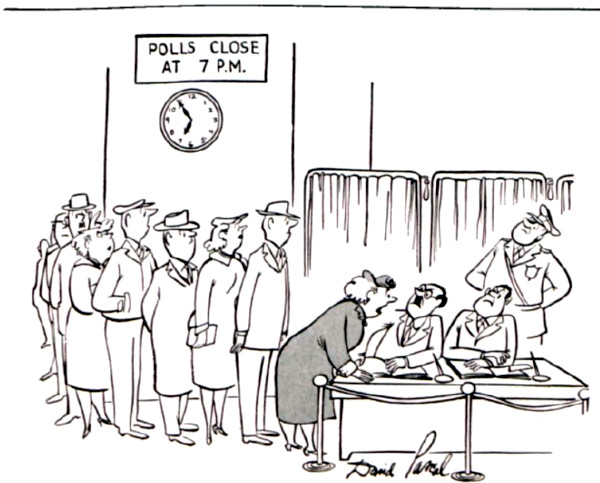

David Pascal

November 5, 1955

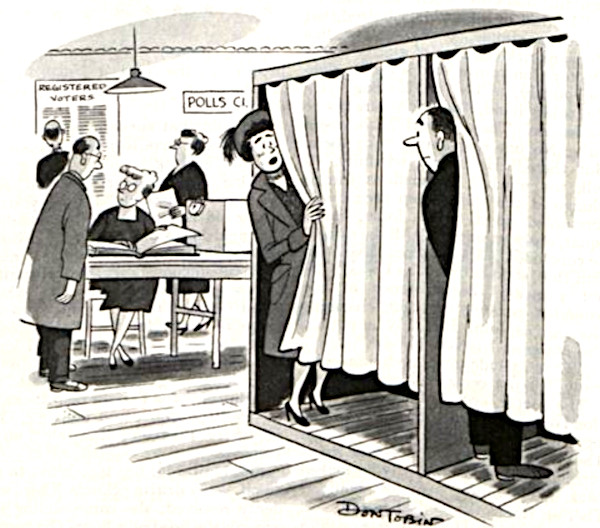

Don Tobin

November 4, 1950

Mary Gibson

November 4, 1944

Want even more laughs? Subscribe to the magazine for cartoons, art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

Songs of America: Patriotism, Protest, and the Music That Made a Nation

The city was thronged. On Thursday, September 3, 1936, tens of thousands of people lined the streets of Des Moines, Iowa, to catch a glimpse of President Franklin D. Roosevelt, who arrived by train at the Rock Island station at noon. Troops from the Fourteenth Cavalry stood at attention as uniformed buglers greeted the commander in chief, who emerged from Pioneer, his private carriage, balanced on the arm of his youngest son, John Roosevelt, smiling broadly and waving to a cheering crowd.

Nearly half a century later, at least one admirer could recall the day in great detail. A young sportscaster at Des Moines’s WHO radio station had been visibly thrilled as he hurried to the window of his offices on Walnut Street to take in the motorcade. “Franklin Roosevelt was the first president I ever saw,” Ronald Reagan told a gathering of Roosevelt family and New Dealers at a 1982 centennial celebration of the 32nd president’s birth.

Speaking in the East Room, Reagan, now the 40th president, paid tribute to the Democrat for whom he had voted four times — in 1932, 1936, 1940, and 1944. “Like Franklin Roosevelt, we know that for free men hope will always be a stronger force than fear, that we only fail when we allow ourselves to be boxed in by the limitations and errors of the past.” The president then offered a toast: to “Happy days — now, again, and always.”

The reference was unmistakable, for Franklin Roosevelt and the song “Happy Days Are Here Again” were inseparable in the political imaginations of Americans. The song entered the nation’s political consciousness at the Democratic National Convention at the Chicago Stadium in 1932. Roosevelt, who was seeking the presidential nomination, had planned to have “Anchors Aweigh” as his theme song, reminding delegates and listeners on the radio of his tenure as assistant secretary of the Navy during the Great War. From his command post at the Congress Hotel, Roosevelt adviser Louis Howe listened to his secretary, a fan of “Happy Days Are Here Again,” sing it out for him. Impressed, the wizened political sent word to the hall to change course: “Happy Days Are Here Again” was now the FDR standard.

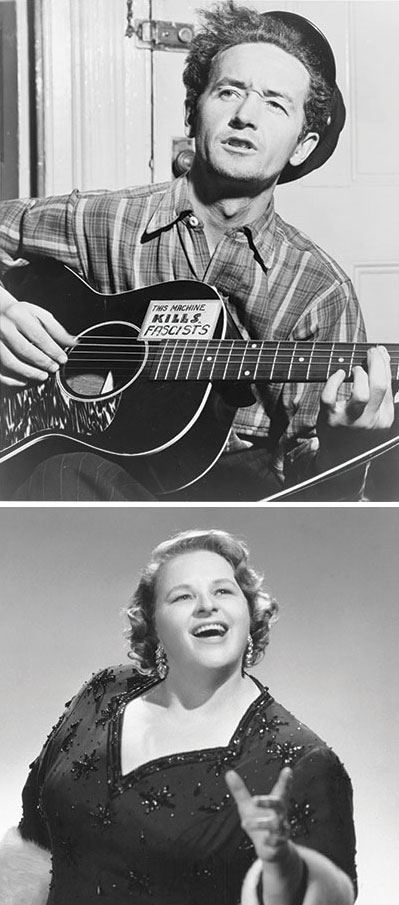

In 1938, the drift toward chaos and bloodshed in Europe prompted the composer Irving Berlin to excavate a song he’d written in 1918, “God Bless America.” He arranged for the singer Kate Smith to perform it on her CBS radio show on Armistice Day 1938, and Smith would record the number in early 1939. In the late 1930s, fearing Hitler, listeners did not have to think hard about what she meant when she spoke of “the storm clouds” gathering “far across the sea” or “the night” that required “a light from above.” Woody Guthrie, though, heard something else in Berlin’s verses: a triumphalism that portrayed America simplistically and sentimentally. And so Guthrie wrote a reply. Initially titled “God Blessed America,” it became “This Land Is Your Land,” a song that grew in popularity during and after World War II. (By 1968, Robert Kennedy was suggesting that “This Land Is Your Land” ought to be the national anthem.)

In wartime, the simpler the song, the more powerful it was, not least because life under fire was so emotionally complicated. The most moving music of the war was the music that moved the troops themselves — songs of longing and loss, of love and hope. There was “We’ll Meet Again,” “You’ll Never Know,” and big band numbers by Glenn Miller, Benny Goodman, and others. It was the age of such songs as “Boogie Woogie Bugle Boy,” and Miller and the Andrews Sisters each had a hit with “Don’t Sit Under the Apple Tree (with Anyone Else but Me).” Miller, whose “Moonlight Serenade” was a signature song, lobbied to join the military once America entered the war. (Born in 1904, he was in his late 30s.) Bing Crosby wrote the government a letter of recommendation, saying that Miller was “a very high type young man, full of resourcefulness, adequately intelligent, and a suitable type to command men or assist in organization.” Commissioned in the Army Air Force, Miller set out, he said, to “put a little more spring into the feet of our marching men and a little more joy into their hearts.” Regular military bands resisted Miller’s attempts to bring the music forward from the Great War to the 1940s. “Look, Captain Miller,” one is said to have complained, “we played those Sousa marches straight in the last war and we did all right, didn’t we?”

“You certainly did, Major,” Miller replied, according to the story. “But tell me one thing: Are you still flying the same planes you flew in the last war, too?”

On a broadcast on Saturday, June 10, 1944, a few days after D-Day, he announced, “It’s been a big week for our side. Over on the beaches of Normandy our boys have fired the opening guns of the long-awaited drive to liberate the world.” The band’s opener that day was “Flying Home,” a jazz number by Lionel Hampton (Ella Fitzgerald would later sing a powerful version) that, for African-American GIs, signified a journey toward the kind of freedom at home they’d been fighting for abroad.

Franklin Roosevelt died of a cerebral hemorrhage on the afternoon of Thursday, April 12, 1945, in his cottage at Warm Springs, Georgia. As the president’s body was being moved to the train for the trip to Washington, a naval chief petty officer, Graham Jackson, tears streaming down his face, played “Going Home” on his accordion.

Woody Guthrie may have offered the most timeless memorial to the fallen Roosevelt. In a song addressed to Eleanor, Guthrie remembered FDR as a providential figure:

Dear Mrs. Roosevelt, don’t hang your head and cry;

His mortal clay is laid away, but his good work fills the sky;

This world was lucky to see him born.

There is, really, nothing more to say on the matter. The world was lucky to see him born.

Jon Meacham is a Pulitzer Prize–winning biographer and author of The Soul of America (2018). Tim McGraw is a Grammy Award-winning country music artist.

From Songs of America: Patriotism, Protest, and the Music That Made a Nation by Jon Meacham & Tim McGraw, published by Random House, an imprint and division of Penguin Random House LLC. Copyright © 2019 by Merewether LLC and Tim McGraw.

This article is featured in the May/June 2020 issue of The Saturday Evening Post. Subscribe to the magazine for more art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

Featured image: Sueddeutsche Zeitung Photo / Alamy Stock Photo.

75 Years Ago: FDR Announces His Run for a Fourth Term

“There are only three certainties in this world,” as the saying used to go, “death, taxes, and Roosevelt.” On July 11, 1944, Franklin Delano Roosevelt further solidified this idiom by becoming the first — and only — U.S. president to announce he would seek a fourth term in office.

In the midst of World War II, Roosevelt decided the country would be best be served with consistency in the executive branch. Unlike in 1940 when he did not openly campaign for re-election, and allowed himself to be drafted at the Democratic Convention, the President declared that he would seek an unprecedented fourth term in the 1944 election.

At the time, The Saturday Evening Post was skeptical of Roosevelt’s performance, calling the New Deal “dictatorial, inept and bumble-puppyish” and his foreign relations puzzling. In a July 22, 1944, editorial that appeared after Roosevelt made his announcement, the Post was particularly critical of Americans’ support of FDR’s foreign policy: “Where, the goggle-eyed voters will be asked, can you find a Republican qualified to chat about matters of state beside Winston Churchill’s bathtub?”

But the Post’s disfavor couldn’t stop the Roosevelt campaign. In selecting a vice president, Roosevelt favored his then VP, Henry A. Wallace, to continue on the ticket in 1944, but when the conservative members of his party objected to Wallace, Roosevelt leaned toward James Byrnes instead. When the more liberal wing of the party objected to Byrnes, Roosevelt chose the middle-of-the-road option, Missouri Senator Harry S. Truman.

Roosevelt would go on to win the presidency; however, he would not finish his term. He succumbed to cerebral hemorrhage in April of 1945, leaving the rest of his term, and the end of the Second World War, to President Truman.

On February 27, 1951, the states would ratify the 22nd Amendment, thereby enshrining in law that presidents could serve only two terms. The Amendment guaranteed Roosevelt’s legacy as the longest serving president in American history.

Featured image: The Life of Franklin D Roosevelt, Archives New Zealand r the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 2.0 Generic license / Wikimedia Commons

The World War II Conference that Altered the Outcome of History

75 years ago, at the height of World War II, the leaders of the United States, the United Kingdom, and the Soviet Union came together for the first time. President Franklin Delano Roosevelt, Prime Minister Winston Churchill, and Premier Joseph Stalin each knew that agreements and concessions had to be made, particularly toward Stalin’s strong desire to open a second front against the Axis powers in Europe. The four-day conference resulted in plans that would be crucial to the winning the war and to shaping the post-war world. Here are five ways that this historic gathering altered the outcome of history.

1. Together, for the First Time

While Churchill had met previously with FDR seven times across two continents and with Stalin twice in Moscow, the three men had never been in the same place at the same time prior to November 28, 1943, the first day of the summit. In fact, FDR and Stalin had never met at all until Stalin greeted FDR at the first meeting. Churchill arrived a half-hour later. The historic gathering not only got the leaders on the same page, but also set the stage for further important conferences in Yalta and Potsdam.

Footage of the Cairo and Tehran Conferences from the FDR Presidential Library.

2. The Hard Part Was the Easy Part

Stalin’s main objective was to get the others to open a second front against the Axis in western continental Europe. He’d been trying to persuade Churchill on this since 1941, but Churchill knew that it would have been hard to do with the Mediterranean and northern Africa in play. However, FDR told Stalin early in the conference that he intended to set a target date to open a second front with a mainland invasion of France in May of 1944.That invasion,code-named Operation Overlord, or, as it became known, D-Day, would ultimately be carried out on June 6. Stalin, knowing that his long-desired second front was in the works, also assented the Soviet Union would enter the war against Japan as soon as Germany was beaten.

3. The Birth of the United Nations Was Assured

The League of Nations hadn’t been properly functional in years, and had done nothing concrete to prevent several crises, including the German expansionism that was a forerunner to World War II. In 1941, FDR, Churchill, and FDR’s aide Harry Hopkins created a “Declaration of the United Nations.” The United Nations was FDR’s term for the Allies. The document mentions “Four Policemen,” which were the major Allied powers of the United States, the United Kingdom, the Soviet Union, and China. By January 2, 1942, representatives of 26 different countries had signed it. At the Tehran conference, FDR addressed the idea to Stalin directly, positing that there needed to be a consistent organization to try to resolve issues and prevent global warfare. All three leaders agreed that they needed to pursue the principle after the war. Conferences and meetings continued to further the project until the first official meeting of the U.N. General Assembly in 1946.

4. They Got Other Countries Involved

Turkey had continued to have relations with Germany into the war, but had promised enter the war on the side of the Allies when the country was more prepared. At the conference, Stalin pledged to aid Turkey if Germany or Bulgaria attacked. By 1944, Turkey broke off their relations with Germany and formally declared war on Germany and Japan early in 1945. While the length of time it took Turkey to get involved was seen by many as a more ceremonial or symbolic decision, it did pave the way for Turkey to join the United Nations and, later, NATO in 1952.

The three leaders also agreed to offer aid to partisans in Yugoslavia who were fighting the Axis in their country. Allied air support and Soviet troops on the ground bolstered the resistance and enabled the Yugoslavian troops to drive back the Axis. Many scholars refer to the Battle of Poljana in May of 1945 as the last battle of World War II in Europe.

Other major moves included Churchill and Stalin discussing a change to Poland’s borders. FDR abstained from the conversation as he didn’t want to alienate Polish-American voters at home. On the other hand, FDR did encourage Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania to be reincorporated into the Soviet Union if the citizens of those countries voted for it.

5. Germany Would Be Divided

Though this would obviously cause many problems later, the powers agreed to an initial idea of dividing a post-war Germany. The theory was that as the driving force behind two world wars, a divided Germany would be less able to precipitate another global conflict. The ultimate result was that the divided Germany became a pivotal location in the later Cold War between East and West until its reunification in 1990.

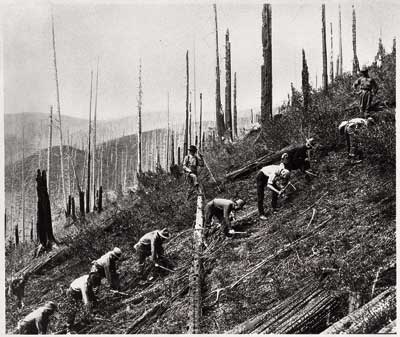

Forester in Chief

Editor’s note: We remember President Franklin Delano Roosevelt as a leader who took the reins of office in the depths of the Great Depression and, in a record-setting span of nearly four terms in office, steered a course back to prosperity. But few of us are aware just how much we owe FDR for his crusading efforts to save and improve America’s forests. “Think 3 billion trees planted, crucial landscapes saved, from the Okefenokee Swamp to the Olympic Mountains — and more acreage conserved than the size of California,” writes historian Nigel Hamilton.

Growing up in Hyde Park, New York, on a 600-acre family farm, FDR had learned at an early age how to manage land. When his father died while the future president was at Harvard, he took over the farm. “It was the beginning of FDR’s lifelong obsession with trees and the importance of trees to the environment,” Hamilton writes.

Just days after his inauguration, Roosevelt ordered that thousands of trees be planted in Hyde Park, New York.

That FDR, with the crushing weight of the Great Depression on his shoulders, found time for planting trees was tangible proof of his long-held conservationist convictions. “Forests, like people, must be constantly productive,” Roosevelt told the Forestry News Digest. “The problems of the future of both are interlocked. American forestry efforts must be consolidated, and advanced.” To that end he wanted to use forests to ease the economic crisis at hand.

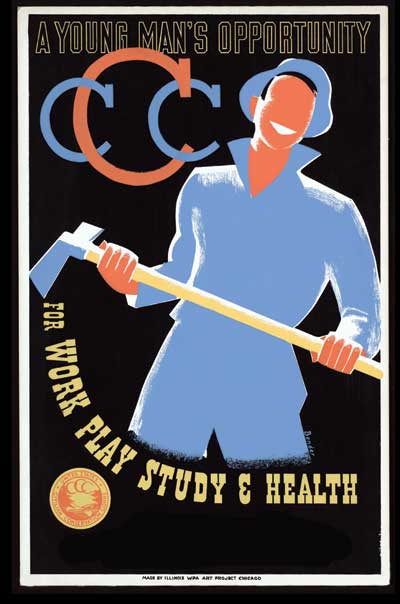

On March 14, 1933, Roosevelt issued a memorandum for the secretaries of war, the interior, labor, and agriculture. “I am asking you to constitute yourselves an informal committee of the Cabinet to coordinate the plans for the proposed Civilian Conservation Corps [CCC]. These plans include the necessity of checking up on all kinds of suggestions that are coming in relating to public works of various kinds. I suggest that the Secretary of the Interior act as a kind of clearing house to digest the suggestions and to discuss them with the other three members of this informal committee.”

FDR convened the first meeting of the quartet of Cabinet members that March. The team was composed of George Dern, from War; Henry A. Wallace, from Agriculture; Harold Ickes, from Interior; and Frances Perkins, from Labor. During the meeting, Roosevelt nonchalantly sketched, on a scrap of paper, a flowchart of the CCC chain of command. As Perkins later explained, Roosevelt “put the dynamite” under his Cabinet members and let them “fumble for their own methods.” Roosevelt envisioned three types of camps: forestry (concentrated in national forest sites); soil (dedicated to combating erosion and implementing other soil conservation measures); and recreational (focused on developing parks and other scenic areas). From the get-go, Ickes was the New Deal’s taskmaster, with the impatience of a drill sergeant. In a symbolic gesture, Ickes ordered the doors to the Interior headquarters locked every morning at 9:01. Showing up late for work, by even a few minutes, meant instant dismissal. Throughout Roosevelt’s first term, Ickes promoted state and national parks with pluck and vigor, rebuffing right-wing senators who claimed the CCC was a Bolshevist threat to democracy.

Frances Perkins — the first female Cabinet officer in U.S. history and one of only two Cabinet secretaries to work for the entirety of Roosevelt’s tenure in the White House (the other being Ickes) — was tasked with coordinating the recruitment and selection of able-bodied CCC enrollees. Initially a quarter of a million unemployed, unmarried “boys” or juniors between ages 18 and 23 (later expanded to 28) were sought. The pool was later widened to include 25,000 veterans of World War I who had fallen on hard times; 25,000 “Local Experienced Men” (LEM) who worked as project leaders in the junior camps; 10,000 Native Americans, who would be assigned to improve reservations; and 5,000 residents of the territories of Alaska, Hawaii, Puerto Rico, and the Virgin Islands. Perkins worried that Roosevelt was biting off more than he could chew. However, as the trees got planted, she soon became a believer.

What made the CCC more than just a dazzling work-relief program was the professional expertise the LEM brought to land reclamation. Skilled young physicians, architects, biologists, teachers, climatologists, and naturalists learned about conservation in a tangible, hands-on way. If not for the Great Depression, these workers would have found themselves engaged in upwardly mobile jobs. But by a twist of fate, as many of their diaries and letters home make clear, these LEM were indoctrinated in New Deal land stewardship principles. Later in life, after World War II, many became environmental warriors, challenging developers who polluted aquifers and unregulated factories that befouled the air.

Courtesy FDR Library

Having developed a working model for the CCC, Roosevelt delivered his plea to launch it with the passage of the Emergency Conservation Work Act, which would provide the authority to create, by statute, a “tree army” to provide employment (plus vocational training) and conserve and develop “the natural resources of the United States.” He sent his bill to Congress on March 21. Roosevelt made it very clear that reforestation projects wouldn’t interfere with “normal employment.” In a message to Congress, Roosevelt stated in part:

I propose to create a Civilian Conservation Corps to be used in simple work, not interfering with normal employment, and confining itself to forestry, the prevention of soil erosion, flood control, and similar projects. …

More important, however, than the material gains will be the moral and spiritual value of such work. The overwhelming majority of unemployed Americans, who are now walking the streets and receiving private or public relief, would infinitely prefer to work. We can take a vast army of these unemployed out into healthful surroundings. We can eliminate to some extent at least the threat that enforced idleness brings to spiritual and moral stability.

Roosevelt did a marvelous job of selling the CCC, answering congressmen’s questions forcefully but politely. At six press conferences, he invoked public works and the CCC. After a round of debate, the 73rd Congress passed S. 598, Public Law No. 5 on March 31, creating the CCC as a temporary emergency work-relief program. Roosevelt’s unstated hope was that what the New Republic called his “tree army” would eventually become a permanent agency.

Roosevelt hired American Federation of Labor leader Robert Fechner as the first director of the CCC. Originally from Chattanooga, Tennessee, Fechner, born in poverty, left school at age 16 and moved to Georgia to become a “candy butcher” on trains. Mild-mannered and collaborative by nature, Fechner was an intrepid labor reformer. Because of his sterling reputation for fairness — as well as his union background — he proved an inspired choice.

By mid-April, the program was coming to life. According to Roosevelt’s estimation, an 11-man CCC crew could, weather permitting, plant 5,000 to 6,000 trees per day. Surrounded by maps of America, the president studied rivers and streams, deserts and forestlands. “I want,” Roosevelt declared, “to personally check the location and scope of the camps.”

Roosevelt’s “tree army” became a legend from the start, and he became a forester-in-chief hero to many conservation groups. As historian David M. Kennedy noted, the public quickly understood that Roosevelt had a “lover’s passion” for trees.

All over America, CCC tent cities popped up like Boy Scout camps; they were soon replaced with rustic barracks. Each company unit of 200 CCC “boys” was a temporary village in itself. All sorts of bylaws, pledges, and rules of engagement were announced. The “CCCers” received three full meals each day and were issued olive-drab uniforms, which included pants, a shirt, gloves, two pairs of underwear, a canteen, and a pair of heavy, steel-toed boots. In time, Roosevelt and Fechner changed the uniform to a spruce-green color for the coat, pants, overseas cap, and mackinaw (the shirt remained olive). “The issuance of a new uniform distinctive from other governmental services will improve the appearance of the corps,” Fechner noted. “It will also aid in building up and maintaining high morale in the camps.”

Unlike the army, there were no guard houses, drills, saluting, or court-martials. But morale was important from 6 a.m. reveille to taps at 10 p.m. At just $30 per month, these young men weren’t going to get rich: $22 to $25 of their pay was mandated to be sent home to their families; what remained was spent at the canteen, on haircuts and snacks, or at the local nickelodeon. Topnotchers were able to boost their salary by becoming technicians. A gag circulated among new enrollees — “Another day, another dollar; a million days, I’ll be a millionaire.”

Uniformed enrollees started working at a breakneck pace to plant millions of trees, restore grass, build check dams, practice rodent control and kill invasive or destructive animals, prevent wildfires, and teach bankrupt farmers how to form soil conservation districts. Particularly concerned about California’s forests — which drought and arid conditions had made hyper-vulnerable to fire — Roosevelt instructed CCC crews to cut a 600-mile Ponderosa Way firebreak along the base of the Sierra Nevada in California, the longest such protective barrier in the nation. The CCC “boys” were also dispatched to do immediate battle in the drought-ravaged Great Plains and the soil-stricken American South. Even Puerto Rico had CCC camps, employing 2,400 men.

Roosevelt never meant the CCC to be a panacea for the systemic woes of the Great Depression, but it did save a vast number of young men from homelessness or, even worse, hopelessness. Roosevelt viewed his “boys” not merely as temporary relief workers, but as makers of a permanent, greener new America. Bursting with optimism, he believed the work-relief experience would transform the young recruits intellectually as well as physically. Teamwork and citizenship and conservation would all be learned in the CCC. Only 37 days after Roosevelt took office, the first CCC enrollee — Henry Rich of Virginia — was dispatched to Camp Roosevelt near Luray, Virginia, located in the 649,500-acre George Washington National Forest, the first camp to open. Six additional CCC camps soon followed in Virginia’s Shenandoah National Park, employing nearly a thousand men to thin overcrowded stands, remove dead chestnut trees, plant saplings, install water systems, build overlooks, and lay stone walls. Between 1933 and 1938, owing to New Deal care, state park acreage in America increased by 70 percent. When FDR became president, Virginia had only two state parks. Determined to rectify the recreation crisis, Roosevelt sent 107,000 CCC enrollees into the state, and within three years, six more parks would open.

Courtesy of The National Archives and Records Administration

Although the CCC actually started in Virginia, it was the trans-Mississippi West that the “boys” quickly occupied like an invading army. In the early and mid-1930s, perhaps the most notable CCC infrastructure work in the West was in Colorado, a state ideally suited for a youth corps. Only five states exceeded Colorado’s native forest acreage. Meanwhile, unemployment was at 25 percent. So in the summer of 1933, 29 CCC camps were established.

Many CCC recruits lived in the gateway town of Estes Park and rode red tourist buses (called “woodpeckers” by locals) up to the construction sites. It took six CCC companies, working on a dozen mountain peaks, to help turn FDR’s “Top of the World” road into a 48-mile reality. “A few months ago I was broke,” Charles Bartell Loomis wrote in Liberty magazine in 1934. “At this writing I am sitting on top of the world. Almost literally so, because National Park No. 1 CCC Camp near Estes Park … is 9,000 feet up. Instead of holding down a park bench or pounding the pavements looking for work, today I have work, plenty of good food, and a view of the sort that people pay money to see.”

In the state of New York, enlistment in the CCC began on April 7 and 8 with 1,800 young unemployed men, all carrying welfare agency certificates, showing up at the Army Building at 39 Whitehall Street in lower Manhattan. Cheers and renditions of “Happy Days Are Here Again” were heard. From the Wall Street area, these initial New York City recruits were bused to Fort Slocum in Westchester County, Fort Hamilton in Brooklyn, and a segregated African-American CCC camp at Fort Dix in New Jersey.

Roosevelt ordered that half of New York’s 66 CCC camps were to be based in state parks. Four innovative New York CCC camps were erected on private land with the cooperation of the owners. Throughout the Adirondacks were numerous old dams, once installed for logging purposes but now collapsed, leaving flats overrun with sumps and bog vegetation. The CCC, by improving these old dams or building new ones, created nine new lakes.

Pennsylvania boasted the second-highest number of CCC camps of any state, trailing only California. Federally funded historical restoration projects took place at Fort Necessity and Valley Forge. Thirty-seven new fire observation towers were erected in state parks. Ickes, an ardent supporter of the NAACP, dispatched an African-American CCC company (led by black military officers) to landscape and renovate Gettysburg National Military Park with the hope that the experience would foster pride in the unit.

What Roosevelt hoped to do by employing youths, whether rural or urban, was to reduce juvenile delinquency. The New Republic went so far as to editorialize that the CCC was Roosevelt’s way to “prevent the nation’s male youth from becoming semi-criminal hitchhikers.” Education was a key component of the camps. Once the young men were officially enrolled, they would take classes in Forestry, Soil Conservation, and Conservation of Natural Resources. CCCers were further required only to do calisthenics, polish their shoes, brush their teeth clean, and maintain a sense of humor.

From inauguration day forward, Roosevelt ably projected the image of an open-hearted liberal who cared mightily about the downtrodden, struggling families, and the homeless. Increasing the size and scope of the federal government to alleviate suffering blindsided the GOP opposition. The CCC was part of this expansion. The public response was so favorable to the CCC that on October 1, 1933, Roosevelt instituted a second period of enrollment. Three months later, 300,000 CCCers were serving America. In 1935, Congress renewed the program, allowing participation to be over 350,000.

CCCers could initially sign up for only six-month stints. Later they could re-up for a total of 18 months, but after that time expired they had to leave the CCC for six months before they could reenlist.

When CCC acceptance letters arrived by mail or telegram or even word of mouth in Missouri, whoops and celebrations usually occurred. While there is no proper documentation of how precisely the CCC office in St. Louis selected the first 25,000 men from Missouri, a distinctive pattern emerged. Most Missouri CCCers were skinny as a rail, Caucasian, averaging an eighth-grade education, and lacking meaningful work experience. After passing a strict physical evaluation and receiving vaccinations, they were clay ready to be molded.

Within a year, over 4,000 CCCers, directed by the National Park Service, fanned out in 22 CCC camps and worked in 15 Missouri state parks, the majority in the Ozarks. A total of 342 examples of “rustic architecture” erected in these state parks by the CCC have been listed in the National Register of Historic Places as of 2015 — an astounding testimonial to the craftsmanship of the CCCers.

Tainting this fine record of achievement in Missouri, however, was the institutionalization of racial prejudice. Although Roosevelt had originally considered integrating the CCC, the program wasn’t sold to Congress as a civil rights crusade. Nor did he want to offend his Democratic political base in the South — which had been instrumental in his election — by attacking Jim Crow. Early on, the CCC created separate companies for African-American enrollees; 250,000 blacks enrolled in 150 “all-Negro” CCC companies throughout the nation from 1933 to 1942. The president’s uninspired “separate but equal” principle regarding the CCC infuriated civil rights groups.

Each Missouri camp had a company commander, a project superintendent, and an educational adviser. There were also chaplains, doctors, silviculturists (tree experts), agronomists, and engineers. At bugle call, the enrollees made their beds and scrubbed the barracks under the watchful eye of an Army foreman. Because the CCC had certain practices in common with the U.S. Army, it isn’t surprising that many military leaders, after initial skepticism, appreciated the CCC. Reserve officers were often in charge of a camp’s transportation needs, day-to-day management, and operational regulations. Part of the attraction of the CCC for many men was the seductive promise of three meals a day. Once the orange juice was downed and plates of eggs and sausage were consumed, the shovel-ax brigade climbed into the pickup trucks that drove them to work sites. At some sites, CCCers drove giant bulldozers and concrete mixers and wielded hydraulic rock-busters and electric saws. It’s been said that the CCC recruits in Missouri were more likely to stink of gasoline than smell of pine.

Not long after the CCC was established, the mushrooming camps each launched their own newspapers or mimeographed newsletters to chronicle daily life. Roosevelt asked Melvin Ryder — who had served on the staff of Stars and Stripes during World War I — to publish from Washington a nationally distributed weekly newspaper, Happy Days, which would feature propagandistic pieces on life in the CCC camps, sporting events, entertainment, and developments in conservation education. Happy Days sometimes printed entries for the best CCC motto. Many were funny, such as “They Came, They Saw(ed), They Conquered,” or bittersweet: “Farewell to Alms.” The New York Daily News approvingly quoted from Happy Days that the CCC motto was “They’ve Made the Good Earth Better.”

Even though the CCC was dissolved in 1942, the work of the “boys” remains visible from coast to coast. Over the course of its nine-year existence, the CCC conserved more than 118 million acres of national resources throughout America — more acreage than all of California. As the plaque at the School of Conservation in Branchville, New Jersey, reads: “These men participated in the world’s most famous conservation program. America will never be able to repay them. All that is great and good about conservation we owe to the CCC.”

From the Archive

Post Editorials Supported the CCC

The Post’s editorial board generally hewed to a conservative line. But when it came to the CCC, a program many on the right vilified as a socialist initiative, our support was wholehearted.

Better Than Welfare

All manner of schemes have been tried and very large sums have been spent for unemployment relief during the past three years. But no attack upon unemployment yet attempted has in it a greater element of hope and inspiration than the emergency conservation work of the Federal Government. This gives 250,000 men the opportunity of working for six months this summer in the nation’s parks and forests in return for food, clothing, medical attention, shelter and $30 a month, most of which the workers are expected to allot to their families at home.

Great numbers of young men have felt themselves a burden upon their families. Relief efforts in general have been directed to the unemployed married worker with dependents; the unmarried young men have been, until now, largely neglected. The forest camp work is aimed at these youths; its purpose is to redeem them from incipient social rebellion, to raise their depressed morale, to build up their health, to help their families with the allotments sent home, and incidentally to accomplish needed work in the forests and parks.

These young men will put in their six months under wholesome and uplifting conditions. They cannot fail to be better citizens for having spent that length of time in constructive manual labor in forests and parks. Nor can they fail to receive new hope and strength. After all, it is dreary business just to feed people and leave them in idleness. Details may prove thorny, but the idea is definitely promising and the attack upon the problem of idle youth is strategic and direct.

—“Hope for Young Men,” Editorial, June 17, 1933

Self-Respect, Confidence, and Fortitude

How might morality be strengthened in the individual? Above all, by strengthening courage; therefore, proximately, by developing hardiness and health; a fit and ready body is a sturdy prop to self-respect, confidence and fortitude. How admirable it would be if the Civilian Conservation Corps would raise its remuneration, widen its purposes, and draw every American youth for a year into its character-forming discipline, its wholesome friendship with forest, stream and sky!

—“Our Morals,” by Will Durant, January 26, 1935

Some Mistakes Were Made

Recent admissions that political influence has been a factor in selecting part of the CCC personnel are exceedingly distasteful to large numbers of fair-minded and unprejudiced people. … Surely, in the hasty finding of work projects for nearly half a million young men, it is more than likely that some mistakes were made. But the idea of putting hundreds of thousands of otherwise idle youths into wholesome outdoor work amid healthful and often beautiful and inspiring surroundings has appealed to everybody.

—“The Trail of the Politician,” Editorial, September 5, 1936