In a Word: So Many Cardinals

Managing editor and logophile Andy Hollandbeck reveals the sometimes surprising roots of common English words and phrases. Remember: Etymology tells us where a word comes from, but not what it means today.

The word cardinal covers a lot of ground in the English language. We’ve got the cardinal directions, cardinal numbers, the cardinals of the Catholic church, cardinal sins and cardinal virtues, and of course the state bird of Indiana, Illinois, Kentucky, Ohio, Virginia, and West Virginia — not to mention my alma mater’s mascot. Cardinal might be the only word to have found a comfortable home in the lexicon of navigation, mathematics, liturgy, and ornithology. But each of these types of cardinal stems etymologically from a common seed of a word.

Cardo was the Latin word for “hinge” — or more broadly, “a pivot or axis on which something turns.” As ancient discussions turned to the cosmological, cardo took on a broader meaning: “the axis points on which the universe rotates around the Earth,” namely, the Earth’s poles. North and south, then, become the first two cardinal directions (from the adjective cardinalis, “serving as a pivot or hinge”), and the other two, east and west, simply fall at right angles to them.

In the fourth century A.D., that hinge took a metaphorical bent, and we start finding mention in Catholic religious texts of the virtutes cardinales, the cardinal virtues (temperance, prudence, justice, and fortitude). Not only do the four cardinal virtues serve as one’s compass for a moral life, but all other moral virtues hinge on these four. The late sixth century saw the emergence of their opposite, the cardinal sins — now more commonly known as the seven deadly sins.

If cardo means “pivot,” one translation of the adjective cardinalis is “pivotal” — first physically and then, as language evolved, metaphorically. Cardinalis came to mean “essential,” and you can’t get more essential to mathematics than the cardinal numbers (in Medieval Latin, cardinalis numeri), a concept that started appearing in texts in the sixth century. Cardinal numbers are the most basic numbers — one, two, three, and so on (there is some debate about whether zero should be included) — as opposed to ordinal numbers — first, second, third, etc. — which place things in order.

Cardinalis also shifted from “essential” to “chief, principal,” and it’s from this meaning that the Catholic church, using Medieval Latin, named certain “ecclesiastical princes” cardinals. These bishops (episcopi cardinales), priests (presbyteri cardinales), and deacons (diaconi cardinales) were senior church leaders and advisors to the Pope, and the election of a new Pope hinged on them. (Today, it’s very rare for someone to be named a cardinal who isn’t an ordained bishop.)

In French, cardinalis in this ecclesiastical sense became cardinal, and it’s from that source that the word was borrowed into English in the early 12th century — but the story of cardinal doesn’t end there.

When performing liturgical rites, Catholic cardinals commonly wear red, signifying the blood of Christ. The specific color of their frocks was so recognizable — and apparently so consistent — that that shade of red was often referred to as cardinal red. American colonists in the 18th century found a red, crested, North American songbird that seemed clothed in that color. The association was so strong that they named the bird the cardinal.

Featured image: Rizwan Mian / Shutterstock

In a Word: The Apostrophe

Managing editor and logophile Andy Hollandbeck reveals the sometimes surprising roots of common English words and phrases. Remember: Etymology tells us where a word comes from, but not what it means today.

September 24 is National Punctuation Day, a time when people across the country, young and old, come together with one voice to talk about how they never really figured out how to use a semicolon.

I exaggerate, of course — but not a lot. Besides, I’m not writing about the semicolon today, but about a much more common punctuation mark that can be just as difficult sometimes: the apostrophe.

We learned in elementary school that the apostrophe is used primarily for two things: to indicate that a letter or letters were omitted (as in don’t and she’ll) and to show possession. As it turns out, these might not be two separate cases at all historically.

For decades, a popular theory on how apostrophe-S came to indicate the possessive in English was that it was a shortening of his used in a way we don’t anymore. Long ago, if you were, for example, taken by some swindler on the street, you might (as the theory goes) tell the story of being fooled by “that slubberdegullion his trick.” “Slubberdegullion his” was then contracted in print, probably to mimic how it would have sounded in speech, so that we have “that slubberdegullion’s trick.”

But that theory isn’t so popular anymore. More recent scholarship focuses on how certain nouns in Old English (genitive masculine and neuter nouns, to be technical) were made possessive by adding –es to them. Merriam-Webster uses the example of cyning, the Old English word for king, which in the possessive was cyninges. So the king’s speech in Old English would have been the cyninges spæc. According to this theory, the E was dropped (because it was not to be pronounced) and the apostrophe inserted to show its absence.

All this removing of letters points to how the punctuation mark got its name as well: The Greek apo “off, away from” was combined with strephein “to turn” to create apostrephein “avert, turn away” — apostrophos prosoidia was a mark showing where a letter had been “turned away” from its usual position. This was borrowed (and shortened) into Latin apostrophus, and eventually came to English (through Middle French) as apostrophe, a punctuation mark showing where a vowel had been omitted because it was not to be pronounced.

Though vowels are the more common letters dropped in contractions, these days any letter or letters might be replaced by that curly little gremlin. (Y’know what I’m sayin’?)

But even before apostrophe had made its mark as, well, a punctuation mark, it had found a life in literature — especially in theater. This type of apostrophe is more literal: It’s a literary device in which a character “turns away” from who they’re talking to in order to speak either to someone else (often someone who is not present) or to a personified inanimate object (O happy dagger!) or abstract concept (Be fickle, fortune!).

Which means that if you’re having a problem with a possessive and you try talking your punctuation into behaving, that’s technically an apostrophe to an apostrophe.

On usage: I mentioned in the beginning that apostrophes primarily served two purposes: to show an omission of letters and to indicate the possessive. You can read primarily as almost exclusively. The apostrophe is not used when you’re making a word plural except in two very specific cases:

- When you need to pluralize a lowercase letter referred to as a letter. A complex algebraic equation, for example, might contain three a’s and two i’s. The apostrophe keeps readers from confusing them with two-letter words. (Did you notice how the letters are italicized, too? That’s a convention from book publishing that you won’t find in newspaper writing, so the apostrophe is quite necessary for clarity there.)

- Many publications call for an apostrophe to pluralize do in the phrase do’s and don’ts — many, but not all; this is a matter of house style and not English grammar. That extra apostrophe aids in quick understanding and avoids the possibility of confusion with the Spanish word for two.

Happy punctuating!

Featured image: TungCheung / Shutterstock

In a Word: Can an Aunt Be Avuncular?

Managing editor and logophile Andy Hollandbeck reveals the sometimes surprising roots of common English words and phrases. Remember: Etymology tells us where a word comes from, but not what it means today.

At its driest, the word avuncular means “of or pertaining to an uncle.” Both the words avuncular and uncle come from the Latin avunculus (literally “little grandfather”), which in ancient Roman times was specifically one’s maternal uncle — one’s mother’s brother. (A paternal uncle was a patruus.)

But that’s just the technical meaning; when we call someone avuncular, we usually mean that they’re kindly and genial, perhaps a bit indulgent. An avuncular person always has a smile and a kind word, and maybe a bad joke that they’ll laugh at even if no one else does.

That sense of avuncular is based on a specific stereotype. There are plenty of uncles who aren’t the slightest bit avuncular in this metaphorical sense. To name a few: Hamlet’s Uncle Claudius, Simba’s Uncle Scar (Claudius’s animated, anthropomorphic analogue), and Harry Potter’s Uncle Vernon. Exactly where the stereotype of the jolly uncle comes from is unclear, but the metaphorical sense of avuncular has been well established in the language and isn’t likely to change anytime soon.

Of course, any discussion of the word avuncular always leads to one question: Is there an equivalent adjective that refers to an aunt? The answer: Of course!

Like uncle, our word aunt traces back to Latin, to amita — but that word specifically designated a paternal aunt. When English was scrounging around for the female equivalent of avuncular, it stuck to the same maternal side of the family. In Latin, one’s mother’s sister was called a matertera, from which we derive the word materteral (or sometimes materterine). All those front-of-mouth consonants and those two sharp Ts don’t exactly roll off the tongue like the more melodious avuncular, so it’s easy to see why the word hasn’t become popular. It doesn’t even sound like a compliment.

So while there is an auntie equivalent to avuncular, the word is ugly and rarely used. It also doesn’t have a common metaphorical sense like avuncular does.

Does that mean — to answer the question posed in the headline — that it’s okay to call your kind, indulgent aunt (or any such woman) avuncular? Probably. Dictionary editors place no explicit gender limitation on the word’s use. And you wouldn’t be alone doing so; a Google search for “avuncular woman” does yield results, but not many.

But if the woman you’re calling avuncular knows where the word comes from, she might not be thrilled with your word choice. It’s probably best, then, if you choose a clearer, less troublesome adjective. It shouldn’t be too difficult; English is full of them.

Featured image: Anatoliy Karlyuk / Shutterstock; hat tip to Ammon Shea of Merriam-Webster for turning me on to marterteral.

In a Word: Fermenting or Fomenting?

Managing editor and logophile Andy Hollandbeck reveals the sometimes surprising roots of common English words and phrases. Remember: Etymology tells us where a word comes from, but not what it means today.

Presidential candidate Joe Biden sent many people rushing to the dictionary on Monday when he accused the president of fomenting violence. Foment isn’t a very common word; is it the right one to use here? What does it mean? And is it anything like ferment?

Foment has long been used to mean “incite” or “stir up,” but it began its life in English in a more mundane way. Though some usage mavens recommend restricting the word ferment to the culinary sphere, it has long been used metaphorically to mean “agitate, cause unrest,” making it as valid and useful as foment in some political discourse.

These two near-synonyms can confuse even the best writers, but there are some key differences in how they should be used.

But first, a little word history:

Like many English culinary terms, ferment was adopted from French, but it goes back to the Latin fermentum, “leavening agent (such as yeast).” When something ferments, it changes organically: bread dough rises, bubbles rise to the top of a brewing ale. Though the word entered English only in the “leavening” sense in the late 14th century, the active change of fermentation opened it up to metaphorical meanings — “agitate, cause unrest” and “to develop organically” — during the English Civil War in the mid-17th century. Today both the literal and metaphorical uses are well-attributed.

You might call foment a physical therapy term — if the phrase physical therapy had been in use half a millennium ago when foment appeared. It too traces back to Latin, to fomentum “warm application, poultice.” When foment found its place in English in the late 14th century (again via French), it referred to the therapeutic use of heat — especially through hot liquids. For example, after a long, hard day, a worker might be advised to foment his sore muscles. But muscles aren’t the only thing that can get heated up, and by the early 1600s, foment also referred to heating up a crowd, that is, inciting or instigating them. Today, its early therapeutic sense is more or less obsolete.

Fermentum and fomentum — I wouldn’t be surprised to learn that ancient Romans confused these words as often as we confuse their Modern English equivalents. But it’s more difficult these days because the metaphorical meanings of ferment and foment can, at times, seem to apply equally to the same situation, and one word may seem more or less appropriate depending only on which side of an argument you fall on.

But there are a few guidelines that can help you find the right word in your own writing:

- Foment always has a negative connotation. No one ever foments peace, love, and understanding.

- Foment is always a transitive verb, meaning it requires an object. Someone foments something, or something is fomented by someone, but something doesn’t foment itself.

- Foment implies an active participant, an agitator. If you’re describing a change — rising political unrest, for example — without someone actively aiding it, you probably want ferment.

- The metaphorical sense of ferment doesn’t need that active participation. An idea or an urge might ferment (“develop naturally or unaided”) in a person before exploding to the surface.

- Which is not to say that ferment can’t also have an active fermenter, though this usage is probably best restricted to writing about food and drink.

- If you’re still confused, remember that you don’t have to use either of them in your own writing. English has a wide array of synonyms to choose from.

Featured image: rangizzz / Shutterstock

In a Word: The Luck of the Hapless

Managing editor and logophile Andy Hollandbeck reveals the sometimes surprising roots of common English words and phrases. Remember: Etymology tells us where a word comes from, but not what it means today.

In 1967’s “Born Under a Bad Sign,” Albert King sang, “If it wasn’t for bad luck, you know I wouldn’t have no luck at all.” We can all empathize with the sentiment today, but for speakers of Middle English, it was more literal: They really had no luck at all.

That is, they didn’t have the word luck, which comes from a Middle Dutch luc and wasn’t common until the late 15th century, the early days of Modern English. What they did have, though, since around the 13th century, was the word hap, adopted from the Old Norse word happ meaning “good luck, chance.” And although hap is rather uncommon on its own today, it’s the lexical link among a number of other common words. Perhaps you’ll recognize some of them.

See what I did there?

Perhaps was coined by adding the Latinate prefix per- “by” to hap “chance.” This combination of Latin and Norse roots makes perhaps a hybrid word, which historically some language snoots have eschewed. Maybe that’s why Shakespeare chose instead to have Hamlet use a totally Latinate alternative in his famous soliloquy: “To sleep, perchance to dream.” Or maybe he just thought it sounded better.

We can call someone who is unlucky or unfortunate hapless — literally “without luck.” The opposite of hapless isn’t hapful but, at least originally, something more recognizable: happy. In most European languages, the modern word that means “happy” began as a word meaning “lucky,” and Modern English is no different.

(Tangent: Gesælig was the Old English word for “happy,” but it underwent rapid and varying development and wound up as our modern silly. This left a hole in the language that was filled by both happy and glad. A deep dive into the tortuous history of silly is a topic for a later column.)

The bad luck that follows the hapless can often lead to an unfortunate event — a mishap, which relies on the prefix mis-, meaning “bad.” And it’s no coincidence that a mishap happens. The verb happen was coined by adding the –en suffix. It originally indicated that something “occurred by chance,” but by the end of the 14th century it just meant “to occur.”

The evolution of English can, at times, seem rather haphazard — that is, characterized by randomness or disorganization, from hap + hazard “risk,” which stems from a French dice game. But sometimes the patterns and connections make perfect sense are right there in front of us. We just have to notice them.

Featured image: Everett Collection / Shutterstock

In a Word: When Potpourri Was Rotten

Managing editor and logophile Andy Hollandbeck reveals the sometimes surprising roots of common English words and phrases. Remember: Etymology tells us where a word comes from, but not what it means today.

Long ago, Spanish cooks developed a slow-cooked stew made of mixed meat and vegetables which they called olla podrida — that’s “rotten pot” in English. No one is entirely sure why that name was chosen; the leading theory is that the slow-cooking process mimicked decomposition.

At any rate, the stew must have been pretty scrumptious, because when the French got a taste of it, they started making it too, but they didn’t call it olla podrida. They translated the name of it literally, calling it pot pourri, French for “rotten pot.”

Both pourri and podrida trace back to the Latin putrescere “to grow rotten,” which is also the root of the English adjectives putrid and putrescent, which refer to decomposition.

The mixed-meat stew pot pourri — along with its name (later pot-pourri and potpourri) — found its way to England in the early 17th century. For English diners, the salient feature of the stew (which one assumes smelled pretty good) was that it was a medley of meats — its putrid past falling by the wayside. By 1750, people were creating new medleys of good-smelling items — primarily dried flowers and spices — and calling it potpourri as well.

The word continued its trek into the metaphorical, and in 1855 we find the first use of potpourri to mean “a miscellaneous collection,” in that case a collection of music. Today, it’s a regular category on Jeopardy! that almost never leads to a clue about decomposing meats, much less rotten pots.

Featured image: Mac Nishimura / Shutterstock

In a Word: The Wisdom and Stupidity of Sophomores

Managing editor and logophile Andy Hollandbeck reveals the sometimes surprising roots of common English words and phrases. Remember: Etymology tells us where a word comes from, but not what it means today.

For better or worse, students are resuming their studies this month, whether at home on a computer or actually going back into the schools. Those beginning their second year of high school or college will be sophomores, a longstanding label with an odd history.

It begins with the Greek sophos, meaning “wise” — a root that appears in philosophy (“love of wisdom”) and Hagia Sophia (“holy wisdom”). In ancient Greece, Sophists were people who would teach students in exchange for payment. Though they taught a number of subjects, Sophists were most recognized for teaching young men the tricks of rhetoric — that is, they taught people how to argue.

Sophists were widely condemned by philosophers of the day (including Socrates and Aristotle), who proclaimed that Sophists and their students were more interest in arguing than in acquiring knowledge. It’s this view of sophistry that came through classical writings and colored our modern definition of sophist (not capitalized): a pedant or dissembler, someone who argues circuitously or deceitfully.

There was also an archaic variant of the word sophist that was a bit less harsh: sophumer basically meant “arguer.” Sometime during the mid-17th century, that word was chosen to describe a student in their second year at a university. It might have even been used in jest at first; the existence of the know-it-all teenager who constantly argues is so widespread that it’s a cliché. (The adjective sophomoric describes this sort of naive overconfidence in one’s knowledge.)

By the end of that century, whether intentionally or simply from a misunderstanding of the word’s history, sophumer drifted into sophomore under the influence of the Greek moros “stupid” — also the root of the word moron.

Sophomore, then, breaks down into the Greek roots sophos and moros, “wise” and “stupid,” making it an oxymoron — as well as etymologically related to the word oxymoron. Whether any individual sophomore partakes more of the former or the latter is entirely up to the student.

Featured image: n_defender / Shutterstock

In a Word: Beauty and Strength in Calisthenics

Managing editor and logophile Andy Hollandbeck reveals the sometimes surprising roots of common English words and phrases. Remember: Etymology tells us where a word comes from, but not what it means today.

When I was in grade school, back in the 1980s, nothing elicited a groan in our daily physical education classes like the word calisthenics. Historically, calisthenics is a collection of exercises that use the body’s own weight as resistance — think push-ups, sit-ups, and burpees — so little is needed in the way of equipment, maybe a bar for balance or some chin-ups. To my younger self, though, calisthenics were practically a punishment: straightforward exercise for the sake of exercise instead of one of the many more fun and interesting forms of physical exertion we could have been enjoying, like dodge ball, an obstacle course, or even square dancing.

What I didn’t know then (though it would scarcely have altered my opinion) was that many of those calisthenics exercises were ancient, that I was doing the same moves Greek and Roman soldiers had done millennia before to prepare their bodies for battle.

Though the exercises themselves are well aged, that word calisthenics is today not even 200 years old. The first part of the word is from a Latinized version of the Greek kallos, “beauty,” making it etymologically related to the “beautiful writing” we call calligraphy. Add to this the Greek sthenos, meaning “strength,” and you have a description not of what calisthenics is but what it was meant to do.

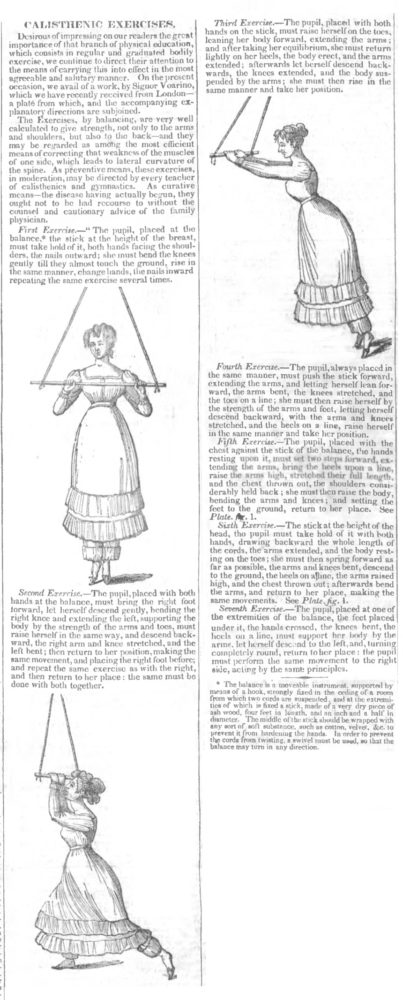

Though the type of exercises we think of as calisthenics have been around since ancient times, the concept called calisthenics — exercises of “beauty and strength” — was developed during the 1820s. They were targeted specifically toward women, for whom other types of exercise were considered too strenuous. As the name implies, calisthenics were employed not only to help women build strength but to help maintain the beauty standards of the day: a nice figure, proper poise, and graceful movement.

Like any other exercise fad (jazzercise, anyone?), calisthenics found its way into the public eye in all manner of ways. We even published calisthenics exercises in the Post. The following clip comes from our April 14, 1832, issue. Notice how the gender of the “pupil” is assumed:

Of course, in our more enlightened times, calisthenics are for everyone, much to the disdain of gymnasiums full of groaning P.E. students.

Featured image: Bojan Milinkov / Shutterstock

In a Word: Gladiators with Gladioluses

This week’s In a Word comes from Zoe Hanquier, the Post’s editorial intern for the summer of 2020. As always, remember: Etymology tells us where a word comes from, but not what it means today.

The word gladiator doesn’t tend to spark comforting images — bloodied bodies, the crumbling Colosseum, a brooding Russell Crowe. To most, the July-blooming flower gladiolus doesn’t come to mind, despite the etymological and historical connection between the two.

Both words share the Latin root gladius, which means “sword.”

We first find the word gladiator in English — taken directly from Latin — in the mid-15th century, meaning “Roman swordsman” or “fighter in public games,” but the practice of gladiatorial fighting started centuries earlier. Historians believe the first gladiator battle happened in the 3rd century B.C. as part of a funeral ceremony to honor a distinguished aristocrat. But soon, gladiators, who were often slaves or prisoners, were fighting to the death in the Roman Empire for the entertainment of thousands.

The word gladiolus arrived in the 1st century. Coined by Pliny the Elder, a Roman naturalist and author of Naturalis Historia, gladiolus literally means “small sword,” referring to the sword-like leaves of the gladiolus species Pliny knew. The flower is part of the iris family and is associated with 40th wedding anniversaries, honor, and infatuation.

Some believe that gladiolus blooms were thrown onto victorious gladiators as celebration, much like the bouquets gifted at the end of performances today. The Dutch continued this tradition into the 1950s and ’60s with successful athletes, but the practice petered out. However, Dutch road bicycle racer and 1978 world champion Gerrie Knetemann is rumored to have invented the phrase de dood of de gladiolen — “death or the gladiolus” — in the ’70s, referring to Roman history and Dutch practice. Louis van Gaal, Dutch trainer of the Manchester United football team, famously said “it is death or the gladiolus,” meaning “all or nothing,” in reference to a difficult match his team later won in 2015. Gaal is credited with bringing the phrase to English.

Gladiolus has changed some since its original naming. Old English shortened it to gladdon, although that word now refers more specifically to a different plant — the “stinking iris” or “roast beef plant,” named for its odor. But we find it returning to its Latin root as gladiol in the mid-15th century — around the same time gladiator was cementing its place in English.

Today, the flower is mostly known as a gladiolus, but there are variations. A few plant-lovers refer to a single flower as a gladiola. Some call a bouquet of them gladiolas, others gladioluses or gladioli. Smart florists skip the linguistic debate in favor of glads.

Regardless of what you call them, you can enjoy their colorful bloom this month and perhaps imagine victorious gladiators being showered with them.

(Andy Hollandbeck; Shutterstock)

In a Word: Getting to the Guts of Nausea

Managing editor and logophile Andy Hollandbeck reveals the sometimes surprising roots of common English words and phrases. Remember: Etymology tells us where a word comes from, but not what it means today.

It’s one of those little coincidences of language evolution that the word nausea — which has the word sea in it right there in plain English — comes from a word referring to sea-sickness. But it isn’t the –sea part of the word that marks its maritime beginnings.

Ancient Greek sailors (and probably those who failed to become sailors) probably noticed early on that the movement aboard a ship on rough seas could sometimes lead to that sickening feeling. That ship was called, in Greek, naus, and so they called that uncomfortable sensation nausia, literally “ship sickness.” This became nausea in Latin, and referred specifically to seasickness to the ancient Romans.

The word eventually made it into English, unaltered from the Latin (probably because it was used in medicine, and Latin was long the language of the educated). Perhaps strangely, the word never seems to have been restricted to seagoing sickness in English. Since it entered the language in the early 15th century, English speakers have been using it to refer to gastric queasiness whether it occurred on land, sea, or (later) air.

That Greek naus is the root of a number of other common English words related to the sea — like nautical and nautilus — and (at least metaphorically) to sailing, including the last syllable of astronaut and cosmonaut.

Featured image: Shutterstock

Logophile: So Much to Love

The word logophile stems from the Greek roots logos “words” and philein “to love” — a logophile is someone who loves words. But there are so many things in this world to love! Can you match up these other –philes with the objects of their affection?

Match the Word with the Thing Loved

-

- An anthophile loves …

- An ailurophile really appreciates …

- A chionophile is keen on …

- A cinephile quite enjoys …

- A cynophile just adores …

- An oenophile can’t get enough of …

- A pogonophile treasures …

- A selachophile is enchanted by …

- A selenophile prizes …

-

- beards

- cats

- dogs

- flowers

- the moon

- movies

- sharks

- snow

- wine

Answers

- d

- b

- h

- f

- c

- i

- a

- g

- e

This article is featured in the January/February 2020 issue of The Saturday Evening Post. Subscribe to the magazine for more art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

Featured image: Shutterstock