Wit’s End: What’s My Love Language? You Don’t Want to Know

Around the holidays, in a year no one could take actual journeys, some of my family members embarked on a journey of self-discovery. One minute they were sitting around the table sharing dumb videos on TikTok; the next minute, they were all experts on their personal “love language.”

They’d stumbled upon an online quiz based on the book The 5 Love Languages. In it, marriage counselor Gary Chapman claims that couples often failed to understand each other’s ways of “expressing and receiving love.” A husband might show his devotion by spending an entire Saturday replacing a broken toilet. The wife might feel hurt that it’s their wedding anniversary and her “surprise gift” is an eyeful of plumber’s butt.

The idea is that, if you know another person’s “love language,” you can tailor your loving behavior so they won’t end up hating you. The online quiz comes in versions for couples, singles, teens, and others.

My husband, 20-something stepdaughter, and preteen daughter took the quiz. After answering a series of questions, they were scored on how much they valued five things: quality time, receiving gifts, physical touch, words of affirmation, and acts of service. The one they valued the most was their “love language.”

Incredibly, after nine months of enforced lockdown, all three of them placed a high value on quality time.

“My main love language is being close to the people I love!” one of them chirped happily across the table.

“Mine too! I feel most loved when my loved one is by my side.”

“My other love language is physical touch. Ideally, I am physically close to the people I love all the time, never more than a room away. I love that!”

As I listened from the kitchen, my blood ran cold. I loved my family, but at this point, togetherness was not at the top of my list. My main love language at the end of 2020 was a solo ticket to Hawaii and $10,000 cash. What I truly desired was a game show jackpot: a fun, life-changing prize for me and me alone!

“Mom! You should take the quiz,” someone called gaily from across the room.

“No. That’s okay. I really have to scrub this tile with a grout brush and . . . can these preserves.”

In truth, I was afraid to take the quiz. The numbers wouldn’t lie; the probing questions would reveal too much. Deep down, my family already suspected I had the “love profile” of a pleasure-seeking misanthrope who wanted to be left alone much of the day. Though I loved being a wife and mom, it could be too much of a good thing, especially now.

Who was going to give me hot stone massages during a shutdown? Who was going to make sure I didn’t grow a thick, dark unibrow like Bert the Muppet? Who was going to utter four of my favorite words — “Pick out a color” — when I needed an hour off to flip through magazines and get my toenails done? Who was going to swing by my Mexican restaurant table and utter six more of my favorite words: “Looks like you need more chips”?

Not these jokers, the ones I lived with. Their love languages included “Mom bringing me a ham sandwich in my room” and “Mom spending an hour every day talking me through Common Core math, a subject she neither likes nor understands.” Every day, I tried to give them the things they loved. No wonder they all gave togetherness high marks!

As for my own preferences, honesty did not seem the best policy. The quiz might dangle things in front of me that I could not pass up, like the ringing silence of profound solitude. What would my family think of that?

I wasn’t about to prove, decisively, that they were all nicer than me.

Eventually, in deep secrecy, I took the quiz. I answered as truthfully as I could, but some of the questions confused me. Many of the choices involved receiving small gifts, or surprise gifts, or thoughtful, just-because gifts. Would I prefer an expensive gift to, say, having someone fold the laundry?

Who the hell would be giving me all these gifts? Trying to imagine this sort of life was a mind-bending exercise. My children were past the age of showering me with drawings, crude pottery, and necklaces made with beads and string. Their gifts to me were now abstract, like “going to church without whining.”

My husband was not a smooth-talking seducer with a diamond in a velvet box in his breast pocket; he was more the toilet-installing type. The task of buying me something seemed to intimidate him a little. I had strong opinions about clothes, jewelry, and pretty much everything else. How could he hope to get it right? Three times a year, he dutifully coughed up a gift, but we were both happier if he did jobs around the house and I shopped for myself.

Because receiving gifts befuddled me, I scored lowest in that love language: a measly 3 percent. My next lowest score, at 17 percent, was quality time. I had a middling interest in physical touch and words of affirmation.

But my highest score by far, at 37 percent, was acts of service. “Absolutely anything you do to ease the burden of responsibilities weighing on an ‘Acts of Service’ person would speak volumes,” the quiz explained. “The words he or she most wants to hear: ‘Let me do that for you.’”

My 12-year-old daughter came upon me pondering these insights. “You finally took the quiz!” she said. “Let me see your results.”

She spent a minute studying my scores with sharp eyes. Then, with a tween’s trademark bluntness, she summed them up: “So, your love language is people being your servant.”

“Don’t tell anyone else about this,” I said.

Then I gave her five dollars to scram.

Featured image: ploy2907; BackWood; Anna Frajtova; Farah Sadikhova; Simakova Mariia / Shutterstock

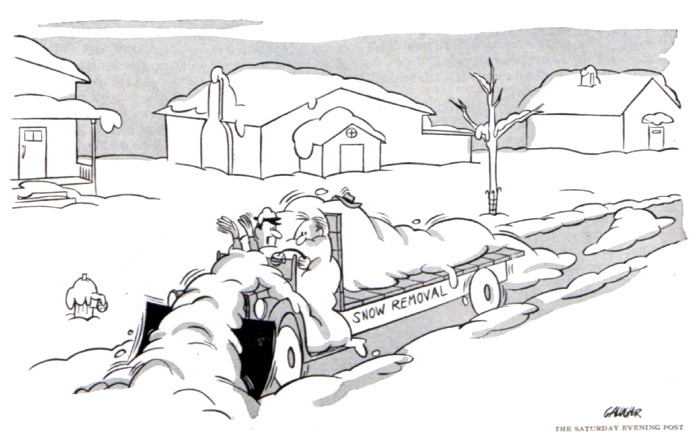

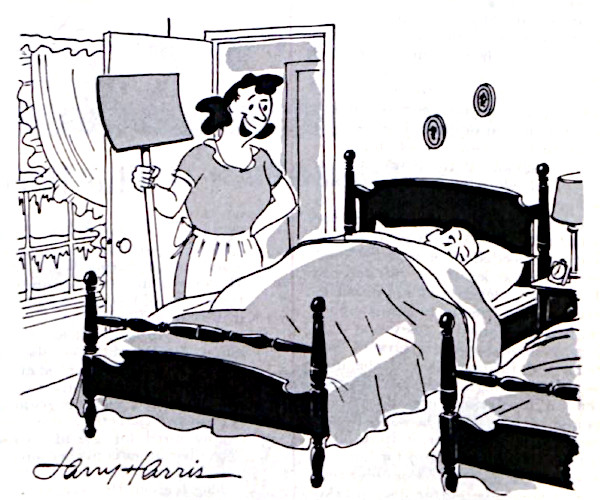

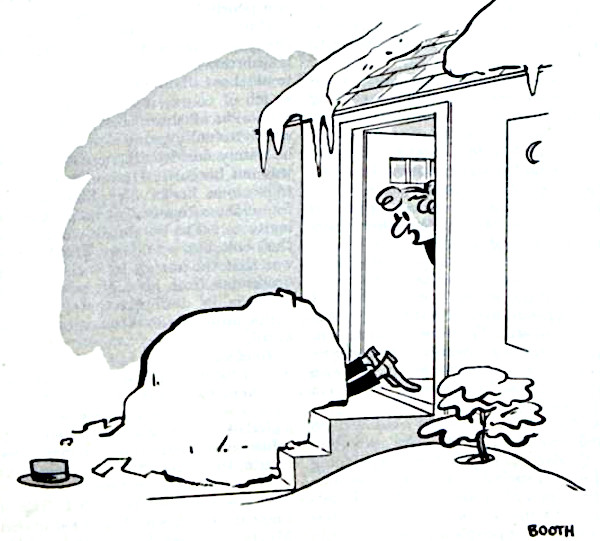

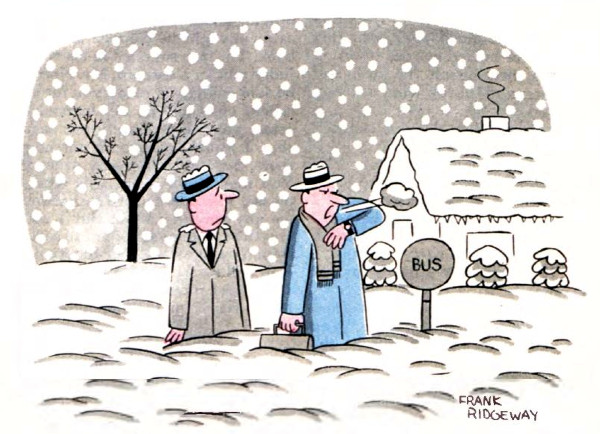

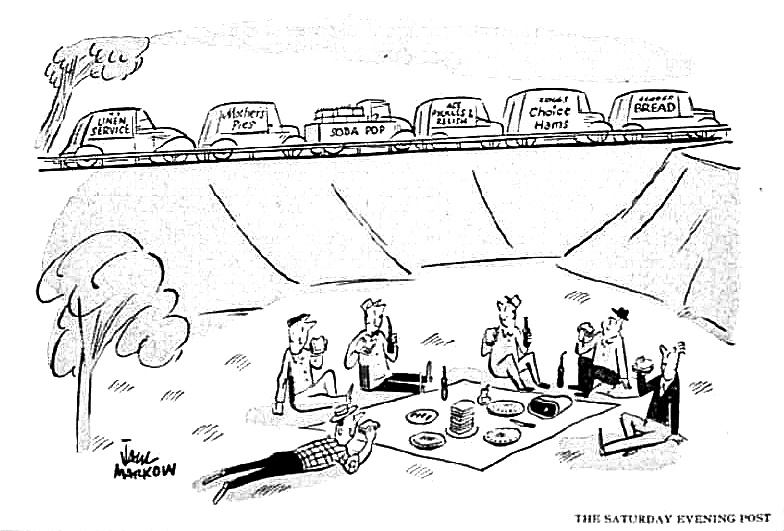

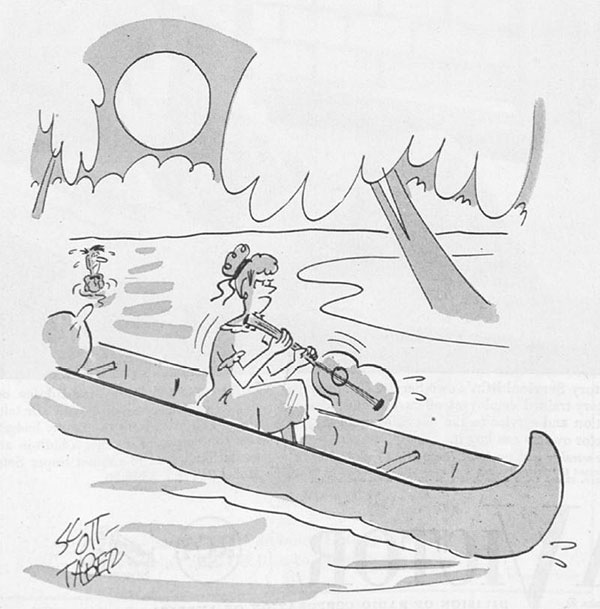

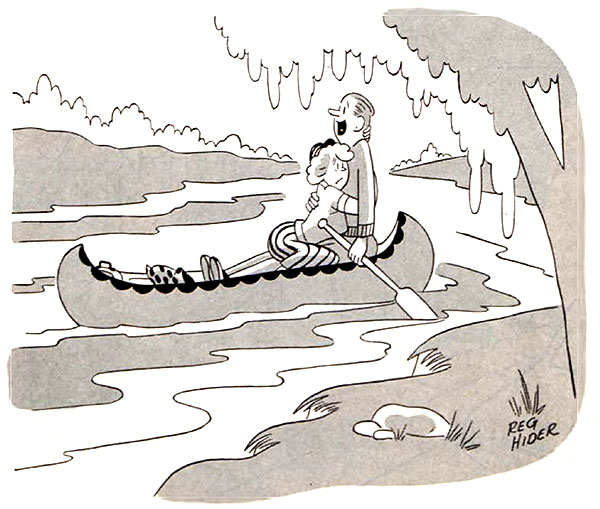

Cartoons: That’s Snow Funny

Want even more laughs? Subscribe to the magazine for cartoons, art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

Gallagher

December 15, 1951

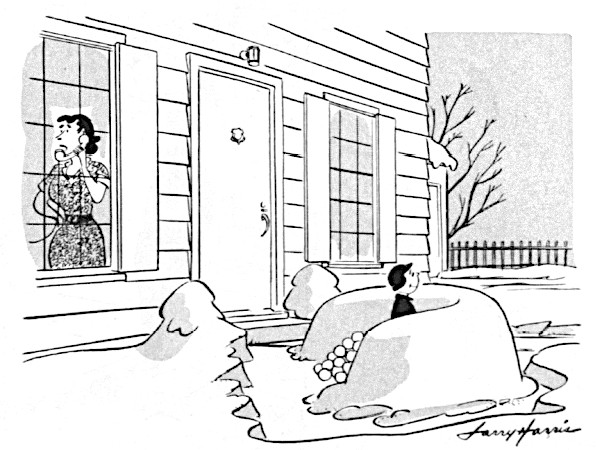

Larry Harris

December 4, 1954

George Booth

November 29, 1952

Frank Ridgeway

November 20, 1954

Larry Harris

November 17, 1951

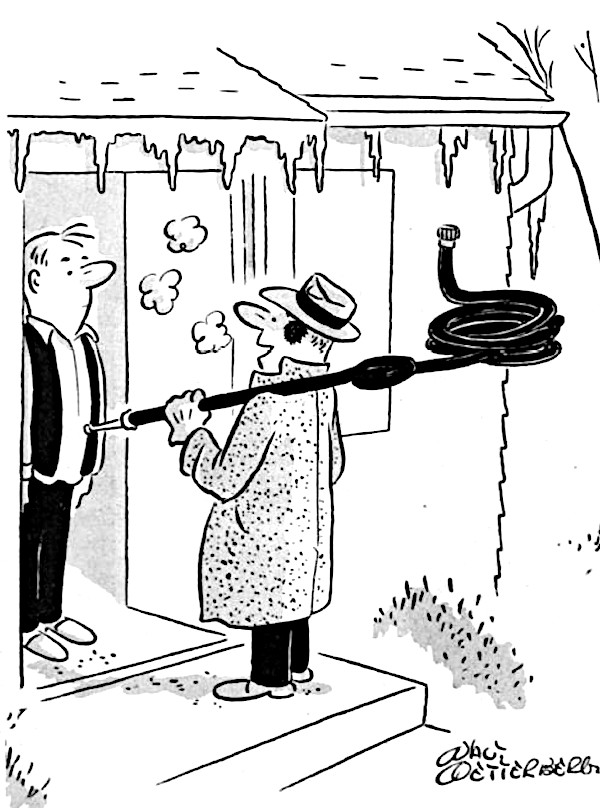

Walt Wetterberg

November 17, 1951

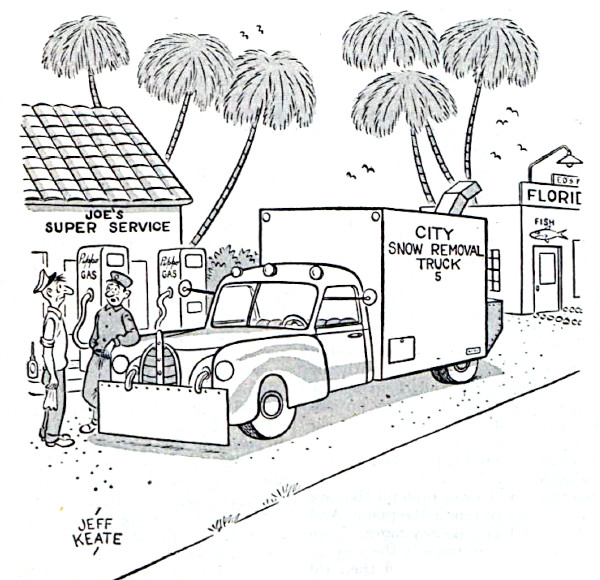

Jeff Keate

February 10, 1951

Chas. Cartwright

February 10, 1951

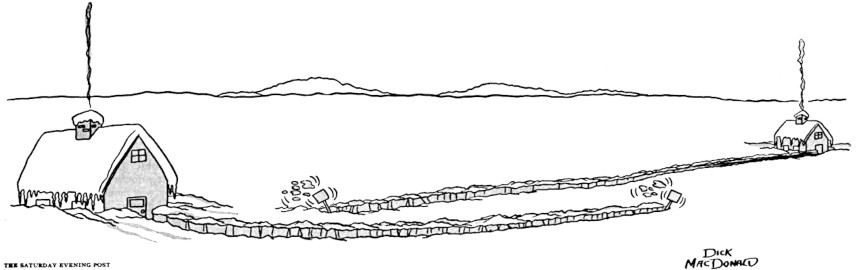

February 6, 1954

Larry Harris

February 2, 1952

Al Johns

January 19, 1952

Henry Boltinoff

December 15, 1951

Want even more laughs? Subscribe to the magazine for cartoons, art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

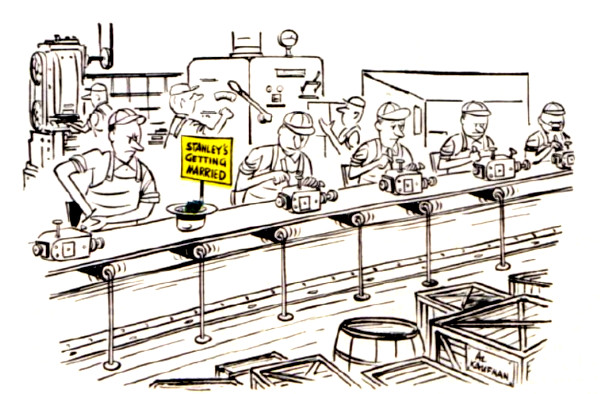

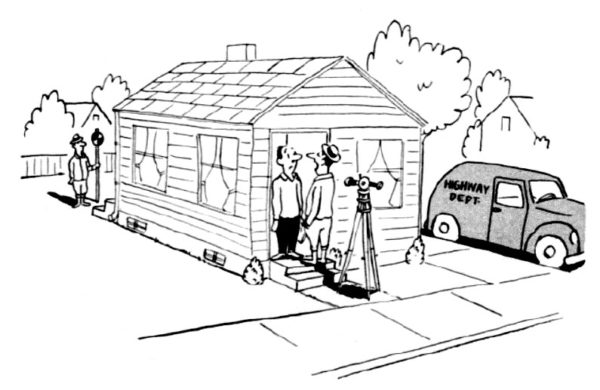

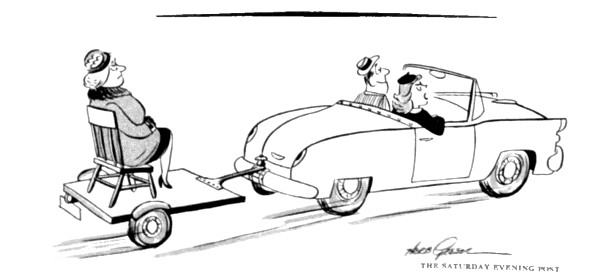

Cartoons: Working Stiffs

Want even more laughs? Subscribe to the magazine for cartoons, art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

Brad Anderson

November 20, 1954

Irwin Caplan

November 19, 1955

Dave Hirsch

October 8, 1955

September 3, 1955

Joseph Zeis

August 20, 1955

Mischa Richter

December 15, 1951

February 27, 1954

Want even more laughs? Subscribe to the magazine for cartoons, art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

Wit’s End: In 2020, a Pet Dragon Is Role Model of the Year

I never wanted to own a bearded dragon. It seemed like the kind of pet Morticia Addams would have: a scaly reptile that hulked inside a tank, one yellow eye fixed on you with hostile indifference.

I preferred likeable forms of animal life, like dogs and kittens. I might, in theory, enjoy an exotic bird, but a lizard held no emotional or aesthetic appeal.

When I was a kid, the bearded dragon’s close relative, the horned toad, often darted across our front porch in the summer. Sometimes we’d catch one and see if we could make it shoot blood out of its eyes: an evolutionary trick to ward off predators. When a coyote attacks the horned toad, one writer explained, “a stream of nasty-tasting blood squirts from the lizard’s eyes, straight into the coyote’s mouth. The coyote steps back, shaking its head from side to side in disgust.”

It never occurred to me to bring one of these things inside the house. My room was a sanctuary of books, toys, and the flowery sundresses I favored. Lizards belonged outside where they would eventually get run over by a car, whatever. Now, where was my rose-patterned tea set?

But suddenly, it was 2020 and I had a daughter of my own. When school and sports shut down in March, she turned to animal shows to pass the time, including a charismatic YouTuber who talked about her bearded dragon, Fitz.

For a tween living under house arrest, it could be worse, I figured. My 11-year-old was not watching Kardashian makeup tutorials or listening to the unbelievably vulgar songs climbing the pop charts. (Seeing the lyrics, I stepped back, shaking my head side to side in disgust.)

Inevitably, though, she began lobbying for her own “beardie.” Though she’d always seemed like a laid-back Californian, suddenly she was giving commanding PowerPoint presentations, selling the idea like a dot-commer to a room of venture capitalist billionaires. She handed out summaries of her research and held Q&A sessions to address our concerns.

Basically, she wore us down. When we green-lighted her idea to buy a newly hatched bearded dragon from a breeder downstate, she burst into tears of joy. It had been a hard slog, but victory was hers!

We met the baby beardie at a FedEx center by the airport, where it had been shipped overnight in a small box. Vaguely jealous that it was still allowed to travel, we signed the papers and took it home. It was a tiny, slender thing, four inches long from tip to tail. We placed it in a well-lit tank, outfitted with its own furniture like a condo.

And so began a new phase of our lives: cohabiting with a reptile. In a stressful and contentious year, when everyone had reverted to their lizard brains, how bad could an actual lizard be?

In fact, the dragon was a model of poise and dignity. It spent a lot of time basking on a rock under a sun lamp. It ate coleslaw mix and live crickets, rousing itself from days of torpor to snap them up with astonishing speed. It often sat in my daughter’s palm or on her shoulder, and seemed to enjoy baths in the bathroom sink.

We could tell when the lizard was nervous because her white underbelly turned splotchy and black. Simple tricks — like papering over the glass tank to reduce visual stimulation, or leaving her alone to furtively poop in her food dish — cheered her up.

If only humans were so simple! Instead of changing color when stressed out, I dashed off angry letters and bought things I didn’t need on the Internet. Perhaps I, too, was overstimulated and should turn off my phone? Life in 2020 was unsettling to both me and the beardie, but her primitive emotions were easier to manage. She was a pro at finding satisfaction in the little things, like munching freeze-dried mealworms or watching the dog leave the room.

On my Zoom calls for work, people frequently asked about the lizard. Everyone was either getting a new pet or thinking about getting one, spooked by the ringing emptiness of their apartments or alarmed that their children spent 15 hours a day on screens. All over town, people were hauling home puppies, gerbils, parakeets, ferrets, snakes, and white mice and giving them 2020 names like Gaslight and Desesperación.

In a tough year, we found, living with animals was therapeutic. Lizards had been around 300 million years. To paraphrase a Victorian writer describing the Mona Lisa, our beardie was “older than the rock on which she sat.” As we humans gripped the rail of the roller coaster that was 2020, our lizard reminded us of a different reality: impassive, ancient, and unchanging. The natural world was not our silly world, and it took the long view.

So many things in 2020 made me step back, shaking my head in disgust, but when I look at our bearded dragon these days, I think: “She’s kind of cute.”

Featured image: ifong / Shutterstock

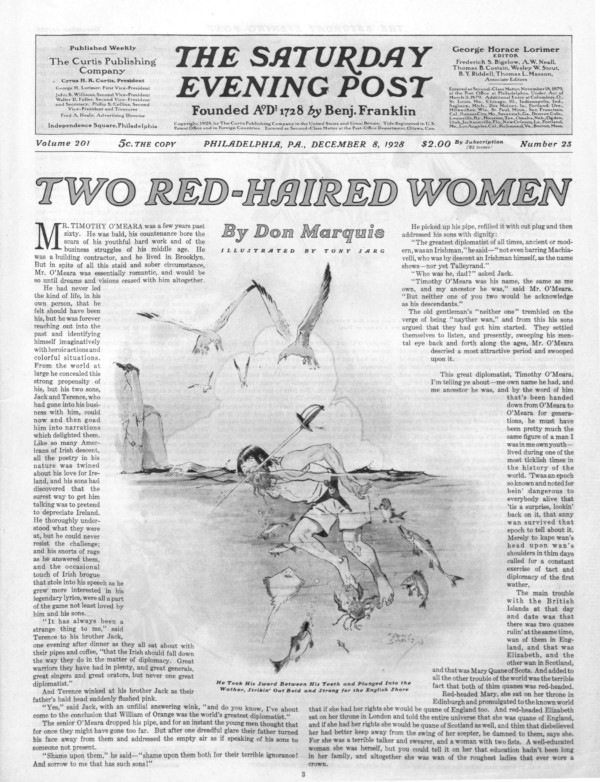

“Two Red-Haired Women” by Don Marquis

Don Marquis was most famous for creating Archy and Mehitable, the iconic comedic cockroach-and-cat duo. However, he was also a frequent contributor to The Saturday Evening Post, writing short stories and columns for the magazine throughout his career. “Two Red-Haired Women” finds Marquis at home in his humorist roots, telling the classic tale of Mary Queen of Scots and Queen Elizabeth from the perspective of a historically inaccurate — yet wildly entertaining — Irish-American father.

Published on December 8, 1928

Mr. Timothy O’Meara was a few years past sixty. He was bald, his countenance bore the scars of his youthful hard work and of the business struggles of his middle age. He was a building contractor, and he lived in Brooklyn.But in spite of all this staid and sober circumstance, Mr. O’Meara was essentially romantic, and would be so until dreams and visions ceased with him altogether.

He had never led the kind of life, in his own person, that he felt should have been his, but he was forever reaching out into the past and identifying himself imaginatively with heroic actions and colorful situations. From the world at large he concealed this strong propensity of his, but his two sons, Jack and Terence, who had gone into his business with him, could now and then goad him into narrations which delighted them. Like so many Americans of Irish descent, all the poetry in his nature was twined about his love for Ireland, and his sons had discovered that the surest way to get him talking was to pretend to depreciate Ireland. He thoroughly understood what they were at, but he could never resist the challenge; and his snorts of rage as he answered them, and the occasional touch of Irish brogue that stole into his speech as he grew more interested in his legendary lyrics, were all a part of the game not least loved by him and his sons.

“It has always been a strange thing to me,” said Terence to his brother Jack, one evening after dinner as they all sat about with their pipes and coffee, “that the Irish should fall down the way they do in the matter of diplomacy. Great warriors they have had in plenty, and great generals, great singers and great orators, but never one great diplomatist.”

And Terence winked at his brother Jack as their father’s bald head suddenly flushed pink.

“Yes,” said Jack, with an unfilial answering wink, “and do you know, I’ve about come to the conclusion that William of Orange was the world’s greatest diplomatist.”

The senior O’Meara dropped his pipe, and for an instant the young men thought that for once they might have gone too far. But after one dreadful glare their father turned his face away from them and addressed the empty air as if speaking of his sons to someone not present.

“Shame upon them,” he said — “shame upon them both for their terrible ignorance! And sorrow to me that has such sons!”

He picked up his pipe, refilled it with cut plug and then addressed his sons with dignity:

“The greatest diplomatist of all times, ancient or modern, was an Irishman,” he said — “not even barring Machiavelli, who was by descent an Irishman himself, as the name shows — nor yet Talleyrand.”

“Who was he, dad?” asked Jack.

“Timothy O’Meara was his name, the same as me own, and my ancestor he was,” said Mr. O’Meara. “But neither one of you two would he acknowledge as his descendants.”

The old gentleman’s “neither one” trembled on the verge of being “nayther wan,” and from this his sons argued that they had got him started. They settled themselves to listen, and presently, sweeping his mental eye back and forth along the ages, Mr. O’Meara descried a most attractive period and swooped upon it.

This great diplomatist, Timothy O’Meara, I’m telling ye about — me own name he had, and me ancestor he was, and by the word of him that’s been handed down from O’Meara to O’Meara for generations, he must have been pretty much the same figure of a man I was in me own youth — lived during one of the most ticklish times in the history of the world. ’Twas an epoch so known and noted for bein’ dangerous to everybody alive that ’tis a surprise, lookin’ hack on it, that anny wan survived that epoch to tell about it. Merely to kape wan’s head upon wan’s shoulders in thim days called for a constant exercise of tact and diplomacy of the first wather.

The main trouble with the British Islands at that day and date was that there was two quanes rulin’ at the same time, wan of them in England, and that was Elizabeth, and the other wan in Scotland, and that was Mary Quane of Scots. And added to all the other trouble of the world was the terrible fact that both of thim quanes was red-headed.

Red-headed Mary, she sat on her throne in Edinburgh and promulgated to the known world that if she had her rights she would be quane of England too. And red-headed Elizabeth sat on her throne in London and told the entire universe that she was quane of England, and if she had her rights she would be quane of Scotland as well, and thim that disbelieved her had better keep away from the swing of her scepter, be damned to them, says she. For she was a terrible talker and swearer, and a woman with two fists. A well-educated woman she was herself, but you could tell it on her that education hadn’t been long in her family, and altogether she was wan of the roughest ladies that ever wore a crown.

Whichever wan of them finally won out as undisputed quane of England, it went without sayin’ that she would claim Ireland too. Everywan always claimed it. None of them foreigners could ever get it into their heads that all Ireland ever asked for was to be let alone in peace and quietness, so that she could fight out her troubles for herself. Fire and sword and the bloody Sassenach was doing their terrible work in Ireland at the very moment I’m speakin’ of.

In the old and ancient days a thousand years before the time I’m tellin’ ye of, as ye would know yourself if ye were not both stuffed to the ears with ignorance and misinformation, Ireland was the world’s greatest country, givin’ her light and learnin’ to all the nations that gathered at her feet.

Most countries has but enough royal blood in thim to have but wan king and wan quane at a time, but in Ireland it’s always been different. There was the king of Ulster and the king of Connaught, the king of Leinster and the king of Munster, and over thim all was the high king of Ireland. And there was a lot more families that would have been sittin’ on thrones thimselves if they but had their rights. And all these kings of Ireland, being proud and unconquerable heroes, was naturally opposed to each other gettin’ away with annything; and that’s how the foreigners was always gettin’ in.

This Timothy O’Meara I’m tellin’ ye about — my ancestor he was — would have been high king of all Ireland himself if he had but had his rights. But you two are willfully ignorant and unworthy of the remarkable men from whom ye sprang, and I don’t know why I’m taking the trouble to enlighten ye.

Time and again Timothy O’Meara rallied his countrymen against the Sassenach, but always they came again, because there was so many of thim. And after years of warfare, during which he had become the most skillful swordsman the world has ever seen and the most sagacious and strategical general, he says to himself wan day, he says:

’Be damned to all this! It’s gettin’ us nowheres at all, at all! As soon as I have wan tin thousand of thim English well whipped and sit down to me bit of porridge and bacon, there’s another tin thousand of thim landed. ’Tis time to try diplomacy.”

And he sat down on the shore of Ireland, a figure of a man like Conachur MacNessa or Finn MacCool himself, and combed his red beard through his fingers, and looked over toward the shore of England and cogitated. And he took off his helmet and scratched the place on top of his head that was growin’ just a trifle bald, as was the premature way with me own hair, and he thought and thought.

“If I could but meet a king of England and talk this matter over with him, face to face and man to man, aquel to aquel and king to king, we might strike a bargain,” says he. “But with no lesser man below the rank of king will Timothy O’Meara bandy words. And I don’t like talkin’ it over with a quane. Women is the divil.”

If he had wan weakness in the world it was a weakness for women. By his appearance as well as his mental qualities and the great fame of his eloquence and warlike deeds, he was always and forever enslavin’ women, and scarcely knowin’ that he’d done it. But after he had seen the plight they was in, and their sufferin’s for love of him, his ginerous heart would always begin to pity the poor craytures and he would be aisy and reassurin’ with thim, and thin, if he wasn’t careful, they’d wrap him around their little fingers. And I hope that I’ll never find out that either wan of you has inherited that tendency.

“I don’t like it — her being a quane instead of a king,” says he. “But somebody’s got to save Ireland. So here goes!”

And with that he took his sword between his teeth and plunged into the wather, strikin’ out bold and strong for the English shore. I was always a great swimmer, and this Timothy O’Meara, me ancestor, was as much at home in the wather as Manannan mac Lir himself.

“Tact,” says he, rollin’ in the seas and spoutin’ wather like a porpoise — “tact is what will save Ireland. Tact and diplomacy!”

Hand over hand he clambered up the rocky coast of Cornwall — as ye’ve seen me, yourselves, go up the framework of a building — and then he batted the sea gulls away from his eyes and shook the salt wather from his beard, and borrowed the first horse he seen and galloped off. Early next mornin’ he was in London, and a surprisin’ city it was to him, what with the crowds and leanin’ houses and high towers and royal troops and all thim bannered palaces; but he was The O’Meara of that time, better than anny of thim, and he would not show his surprise to the Sassenach. He paused but long enough to trim his beard and dress himself in the latest style, and well before noon he set off to the quane’s palace.

’Twas no trouble at all for him to identify that same. If the two of ye were not sunk deep in ignorance and illiteracy, which ye are, ye would know that Quane Elizabeth’s palace in that day was the most splendid and stately edifice ever erected by anny monarch annywheres outside of ancient Ireland. Through all the outer magnificence strode Timothy O’Meara with his head up, and that in his eye that forbade a question by anny underling. Past the courts and guards and fountains tannin’ wine, and all the enginery and paraphernalia of great and royal luxury he went, till he came to a flight of broad steps that led upward to a most magnificent hall.

And all over thim steps, and at the top of thim, in front of the big gilded doors that led into the hall of state, was a crowd of the most risplindent courtiers on guard — English they was, most of thim, but with a sprinklin’ of Scotch and a few Spaniards and Frinch, and two or three Irish — bad cess to the traitors! Knights and baronets, earls and dukes and princes, ginerals and admirals, by the gay and splendid look of thim, with their jewels and velvets, that’s what they was, no less.

“And who are ye,” says wan swaggerin’ sprig of nobility, with his hand on his sword hilt as Tim laid hold upon the big door, “that thinks he can crash the gate of the quane’s own hall, without lave or likin’ from annywan?”

“I’m The O’Meara,” says Tim, and he gave the young popinjay a backhand swipe that tumbled him down the stairs. None of us O’Mearas has ever had great patience with empty impertinence, then or now.

Fifty swords were out in a second and they ringed him round.

“I’m here from Ireland,” says Tim, “to see the quane of England. If diplomacy was not me intintion I’d cut me way through youse. But if there’s anny of ye wishful for a little sport, now’s the time to spake up. Diplomatist though I be, I’m the man for ye!”

Siviral of thim proved to be wishful, and in less than ten minutes he decimated three of thim Englishmen with a Scottish claymore, and then he accommodated an aquel number of Scotchmen with an English broadsword, and thin he took in his fist wan of thim Spanish rapiers and gave a fencin’ lesson to a Frenchman, and then he says:

“Gintlemen, what man is the master of the British Islands at any form of fencin’ with anny kind of soord?”

“The O’Meara is!” says they all, with wan hearty voice.

“’Tis well ye English and Scotch know it,” says Tim. “But is there anny Welshman here has his doubts?”

But if there was anny Welshman there, he said nothing disputatious about it. And just then the lord chancellor flung open the big door to the quane’s hall, and he says:

“And what’s all this racket of weapons out here? Have ye no more sinse than to be scrapin’ steel almost in Her Majisty’s very prisince?”

“’Tis I that am the responsible party,” says Tim. “And who might you be?” says the lord chancellor. “I’m The O’Meara,” says Tim. “So!” says the lord chancellor. “The boldest rebel in Ireland! I’ve heard of ye!”

“I’m no rebel,” says Tim, “but a free man. And were I not here on a diplomatic mission I’d bloody your mouth for ye.” But as it was, he remembered his tact and did nothing but twist the old boy’s whiskers a swipe or two.

“Stop your blattin’, ye old goat,” sings out Quane Elizabeth to the lord chancellor from her throne, “and bring The O’Meara to me, if ’tis he indeed that has his clutches on you. ’Tis long I have wanted to meet that impudent warrior!” Timothy O’Meara — my ancestor he was — walked up the hall to where the quane set on her throne, and he made her the bow that anny gentleman of breedin’ makes to a lady, but divil the bit did he kneel to her, and he stood and looked her in the eye and she sat there and looked back at him.

“Ye’re the bold rebel, Timothy O’Meara,” says Queen Elizabeth.

“I’ve heard ye’re no coward yerself, Your Majisty,” says Tim.

“Do ye know anny reason why I should not have your head struck from your shoulders?” says the quane.

“Siviral,” says Tim. “Such as?” says she. “Faith,” says he, looking pointedly at her own red hair, “if ye had the same love for red hair in a man that I have for red hair in a woman, ye’d never think of it,” says he. “Besides which, ’twould be to the great detriment of me neck.”

“That’s what they all say,” says the quane.

And with that, they smiled at each other, and all the guards and courtiers and dukes and counselors that was gathered about smiled also. A high-tempered and imperious woman was this Quane Elizabeth, and there was something free and commandin’ in her that caught the fancy of me bold Timothy from the start. Not that she was anny great beauty; her nose was a trifle too long for that, but there was the divil’s own intelligence in her eyes, and a humorsome way about her mouth, and a kind of dangerous element about her altogether that made her fascinatin’ to Timothy O’Meara at wance, for he was wan of thim men that seeks out the prisince of peril for the pure enjoyment of facin’ it. Thim intelligent women has always had a great fascination for meself; and there was manny a beautiful woman that loved Tim O’Meara that he cared less for than Queen Elizabeth, for all her long nose and bad manners and the way she painted her face. As for Tim, there was never yet the woman looked at the big lad without her imagination was stirred, nor was she ever quite the same woman afterward.

“And for what do ye come here so bold and proud, with your neck so stiff and your hand upon your sword?” says the quane.

“I’m here as the discendant of the ancient kings of Ireland, rightful and historical,” says Timothy O’Meara — “them that had their high seats on the hill of Tara and was the masters of war and wisdom. I bear word to ye from the green island that’s never been conquered yet, and the word I bring is that ye might as well quit tryin’! For a thousand years we’ve been assaulted and tricked and massacred by the bulcheens of the world — the Dane, the Norman and the Sassenach — but we’re still strong-hearted in the field and fightin’ back. And in a thousand years from now, if there’s wan heart still beatin’ there, ’twill be a heart that’s free and strong, aven though it beats alone against a million tyrants. Ye cannot conquer us, quane, but ye can take away thim troops off a people that was never yours and never will be; ye can do that free and ginerous without conditions, and ye’ll find a ginerosity springin’ up to equal yours, and after while ’tis Ireland may forgive ye and be your friend.”

“’Tis I that am the quane of Ireland!” says Elizabeth.

’Twas on the tip of The O’Meara’s tongue to rejoin with heat, but he remembered his diplomacy in the nick of time, and all he said was: “Some dirty, lyin’ old fool of a prime minister has been stuffin’ thim beautiful ears of yours with nonsinse and falsehoods, Your Majisty.”

Quane Elizabeth sat and thought, and frowned at him and sized him up, the while she picked her teeth with the end of her scepter, for good manners was only an occasional practice with that quane. Then she sent everywan else from the room, and she says:

“Mr. O’Meara, in me heart I know ye’re not far wrong. But ’tis wan of the obsessions of this people of mine that the ruler of England should be the ruler of Ireland too. ’Twould not be so aisy as ye seem to think — doing what ye ask. But if I was to take the risk and give up Ireland to ye, tell me this: What would ye give me in return?”

“Annything ye want,” says Tim. “Scotland’s what I want,” says she. “’Tis yours in six weeks,” says Timothy, “if ye’ll give me but half the men ye have blunderin’ about Ireland, and I’ll take a few hundred of me own Irishmen that has learned thim English the rudiments of fightin’.”

Annything else?” says the quane. “France, if ye’d like it,” says Tim. “Annything else?” says the quane, speakin’ but little above a whisper this time, but with that tilt of the head that says:

Well, what about it?

Tim, he was wan of thim unfortunate men that’s cursed with a knowledge of what ye can do and when ye can do it, and he stepped up to the throne and dropped his arm about her. But he only kissed her wance or twice, rememberin’ his diplomacy just in time, and not wantin’ to commit himself with irrevocability.

“Tim,” says she, “can’t ye forget Ireland and stay in London for a while? I need men like yoursilf. Ye should be commander of me armies and admiral of me navies and prime minister of all me councils, and if there’s annything more than that ye might want, ye’d have but to put the name on it, Tim.”

Tim thinks quick and diplomatic to himself, wonderin’ whether it would be for the benefit of Ireland if he married her, or whether that would work out to the detriment of both Ireland and himself in the long run. “Marriage,” says he, tentative and judicial, and risking another kiss on her for the sake of Ireland, “is wan of thim yes-and-no games, Your Majisty.”

“Who said annything about marriage?” says she, twisting loose and frowning on him. “Be damned to marriage! The Maiden Queen was I born and the Maiden Queen will I die. I’m a broad-minded woman, with very few prejudices, but the wan strong prejudice I have is against a quane gettin’ married. What I was thinkin’ of was, maybe we might be engaged for a while.”

“I hear Your Majisty’s already been engaged a good deal to a lot of these noble gazabos,” says Tim, “including King Philip of Spain and siviral dukes.”

“Thim others is but statecraft, Timothy,” says she. “There’s little that’s personal in thim. With you and me ’twould be far different.”

“Well, now then, Your Majisty,” says Tim, “ye put me in mind of a funeral I noticed this morning as I came past Westminster Abbey. They told me they was buryin’ that part of the Duke of Norfolk from his collar down, and the part of him from his collar up is exposed to the wind and weather on Temple Bar; and between the two, where his neck ought to be, there’s three companies of royal halberdiers. Separations like that must be painful, followin’ a long engagement like yours and his was.”

“He wasn’t executed because he was engaged to me, Timothy. He was executed because of high treason. He went and proposed matrimony to that Mary Stuart, who calls herself quane of Scotland.”

And when she mentioned Mary Stuart’s name there came an expression on her face that made Tim more diplomatic than ever about getting himself engaged to her.

“And Scotland,” he says, getting back to where they was, “is yours, Your Majisty, within two months after ye’ve evacuated Ireland.”

She pushed him away from her, and she gave him a long look and she laughed.

“Ye trade too fast, Mr. O’Meara,” she says. “The way of it will be this: Me troops will leave Ireland the day after I’m crowned quane of Scotland at Edinburgh, with Mary Stuart’s head in a basket at me feet.”

And move her from that decision he could not, neither with the power of reason nor with the blandishments of his magnetic and affectionate personality. For three days, off and on, they debated that point, while she entertained him royal at her palace, but at the end of that time she was just as firm and fixed as at the beginning: Ireland she would not give up to him till first he’d conquered Scotland for her. And on the morning of the fourth day he leaped on his horse and galloped north to scout the ground over alone.

Through sun and moon and rain he galloped, day and night, commandeerin’ cattle in the quane’s name as he needed them, up the middle of England and through them Cheviot Hills, keepin’ his strategical eye peeled for military positions as he rode; and ’twas on an afternoon of blowin’ wind and streaks of sunlight through the clouds he topped a ridge and looked across land and wather upon the tall town of Edinburgh, wavin’ her plumes of smoke a dozen miles away.

And betwixt the sight of that and the reach of his mind there came the whistle of feathers and the scream of a bird, and right in the air forninst his station a falcon stooped with a whir of silver bells and struck all his blades into the red life of a heron. But no time had Timothy to think of thim rumpled feathers, for with a shout and a rattle of hoofs, a lady all in green stormed up the rise before him on a white palfrey, and a man, ridin’ after her, bent from his saddle and snatchin’ at her bridle.

“Ruthven!” she cried, and lashed out at him with her riding whip. And with that both reined their horses to a prancing stand.

“I have my Lord Murray’s orders never to let ye ride alone,” says the man, sullen and black.

“That for my Lord Murray’s orders!” cries the woman, and with the word she gave her horse the spur and was on him like the spring of a wildcat. Twice she cut him on the face, while the air danced with the forefeet of horses and the man swayed in his saddle; and if it had been a blade instead of a whip ’twould have been the fellow’s finish that instant. Back staggered his horse, and he caught his dropped reins again in one hand and laid the other on his dagger.

“Ruthven!” she cried again, and raised her whip once more. But me bold Tim spurred between them.

“Will ye draw steel on a lady!” he roared, whirlin’ out his sword with the word. The man let go the dagger and out with his own sword. Timothy O’Meara — me ancestor he was — was too distinguished a swordsman to trifle with a foe just for the mere pleasure of it, and now the blood of the ancient chiefs of Ireland was singin’ through him, and with one neat backhand sweep he sent that fellow’s head rollin’ down the hill and his horse galloped off with the rest of him.

“’Twas a good blow,” says the lady.

“I misdoubt,” says Tim, lookin’ after the horse, “but that I was a trifle hasty with him. But ’tis not in me character to see a man offer insult to a lady.”

“’Tis no great matter,” says the lady; “there’s plenty more where he comes from — sons and fathers and cousins.”

“Who was he?” says Tim.

“Wan of them Ruthvens,” says she. “They’re always in trouble. And who are ye, me bold knight?”

“I’m The O’Meara,” says Tim, “from Ireland.”

“I’ve heard of ye,” says she, “as who in the world has not? I’m Mary Stuart,” she says.

“The quane of Scotland?” he says.

“And France,” says she. “And England, too, if I but had me rights.”

“Be gosh,” says Tim, rash and impulsive, and clean forgetful for the moment of all his diplomacy, “but I’ll make ye quane of England the day ye say the word. And yes,” he says, says he, “and on top of that, the quane of Ireland too.”

For I had been lookin’ hard at her, and her at me, and it had come over me with a rush —

Mr. O’Meara suddenly checked himself, his bald head flushing, and gave his attention to his pipe but no notice at all to his two sons, who were grinning broadly and ironically at him. He cleaned his pipe with elaborate care, lighted it again and resumed.

Timothy O’Meara had been looking hard at her, as she at him, and it had come over him with a rush that if Ireland was to have a quane, this woman was the quane for Ireland. Red was her hair, and it was blowin’ in the wind — a brown red the most of it, but with streaks of gold red twisted through it — and hazel was her eyes, but there was glints of gold in them, too, and through that quane’s white skin ye could mark at times the leap and circlin’ of her blood. A golden woman she was, and there was the sparkle of red wine in her, too, and there’s been no language known to any bard could tell her beauty nor the wild intoxication from it — nor no harper to sing it, neither, since the old and ancient days when we chanted of the only woman that was ever more beautiful than she, and that was Deirdre herself, the Troubler of Ireland and the world.

“No man,” says he, “could look at ye, Quane Mary, and not want to give ye all the kingdoms of the earth.”

“Wan kingdom at a time,” says she, and laughed; and if he had not been already hers that laughter would have finished him. And as for her — I will keep back no secrets from ye — he had upon her the usual and instantaneous effect that he had upon all mortal women everywhere and always. “From what I’ve heard of ye,” says she, “and what I’ve seen myself, I think ye could make me quane of England in good earnest.”

“There’s but wan thing I ask of ye, Quane Mary,” says Tim, all his diplomacy coming back to him again, “and ’tis that when ye’re quane of England ye’ll let Ireland go her own way, alone and free. And I think ye’d better sign a paper to that effect before I put ye on the throne.”

“I’ll sign it the day I’m crowned in London,” says Mary, “and that’s a good deal to give up to you, Mr. O’Meara, for the fact is that I’m quane of Ireland by rights now, and I’ll have the double right when I’m quane of England.”

“Now, now, now,” says Tim, “don’t talk to me like that, or I’ll think there’s more honey than wisdom on thim lips of yours. We can’t deal on thim terms at all, at all,” says he.

With that she give him a look out of her eye. “And isn’t there anny other terms you and me could deal on, Timothy O’Meara?” says she. And with that look there went a smile.

Now Tim was wan of thim unfortunate men, as I’ve tried to show youse, who knew by instinct what wan of thim looks and wan of thim smiles called for — unfortunate, I say, because his impulses was forever gettin’ into the way of his diplomacy. He slipped his arm around her and lifted her from her horse to his own.

“Moira,” he says, “if anny woman in the world could make me forget me juty to Ireland, ’twould be yourself!” And with that he kissed her wance or twice. “But no woman could,” says he. And with that he kissed her again. “Not aven you,” says he. And what more was said and done in the next few minutes, he was always too much of a gentleman to tell annywan, and your father will lave it to your own imaginations.

“There’s wan other thing I would dearly love to have, Timothy darlint,” says she afther while, when she was back on her own horse again, “and that’s me Cousin Elizabeth’s head in a basket.”

“We’ll see about that, Moira,” says Tim, aisy and tactful, not wishin’ to commit himself to annything. And with that the rest of her huntin’ party, which she had outridden and lost, came jinglin’ up. ’Twas to Holyrood Castle they went, and there Quane Mary entertained him free and royal for three days. ’Twas on the second day the quane proposed marriage to him.

“I hear Your Majisty is married already,” says Tim, diplomatic.

“Didn’t ye hear that terrible explosion last night?” says Mary. “That was me husband getting himself blown up with gunpowder, out in the suburbs. He was always a clumsy fellow, that Darnley.” And she stooped down and fixed wan of the rugs on the floor. “Mary Livingstone,” she says to a lady in waitin’, with a kind of mist in her eyes, “you girls have got no affection for your quane! I have always to be straightenin’ out this rug for mesilf.”

“Your Majesty knows we love you,” says Mary Livingstone, with a curtsy, “but ye must remember we have not the same motive as yourself for rememberin’ what that spot on the floor is. There’s times when we forget just where it was Davy Rizzio was stabbed.”

“Nobody loves me,” says the quane, lookin’ at Tim, “neither man nor woman.”

If the whole court hadn’t been there, Tim would have showed her that minute she was wrong, as who wouldn’t? But he kept hold of his diplomacy.

“Your Majisty,” says he, being careful to call her that in public, “I’ve heard some talk that the Earl of Bothwell would be your next husband.”

“Why, I thought that the Earl of Bothwell had met with a fatal accident!” says the quane, looking surprised and speakin’ to a group of them noblemen standin’ about. “Lindsay,” she says, “or Douglas, or some of you that’s not too near related to him, won’t you be so kind as to go and bring the quane the very latest news about the Earl of Bothwell?” And six of them bullies started out of the room at once, lickin’ their chops. “Remember, now,” she calls after them; “bring back to me nothin’ but the very latest news of what poor Bothwell’s fate has been!”

And with that she turned a dazzlin’ smile on Tim, as if to say obstacles to their matrimony seemed to be eliminating themselves.

“And now,” says she, lookin’ around on the rest of the gentlemen, “is there anny wan else present I’ve promised to marry?”

“Your Majisty mentioned it to me wan day,” says the Lord of the Isles, feelin’ unaisy of his neck, “but I got the idea Your Majisty was just havin’ wan of your bursts of mirriment.”

“What,” says she; “is the man tellin’ me he don’t want to marry me? Speak up,” she says: “do ye want to marry me or don’t ye?”

“I’m willin’ to let bygones be bygones, please Your Majisty, if you are,” says the Lord of the Isles.

“Never in the world,” says Mary, turning a bright and beautiful pink, “was such an insult offered to a quane before in broad daylight, and her sittin’ on her throne. Don’t,” she says, covering her face with her hands”don’t anny of you gentlemen be too cruel with the man that uttered it, for ’tis plain he’s not sane and accountable for his actions. And don’t,” she says, peeking through her fingers—”don’t be too slow with him, neither!” And the wans that led him out wasn’t.

“Timothy O’Meara,” says she to him, “I’ll have a word in private with ye,” and gave him one of them looks and dismissed the court. Wan word in private between them two always led to another, and so on and on, in the way of love and logic. But at the end of two days’ discourse betwixt thim of this and that, there was wan thing that Quane Mary was just as fixed and firm about as at the beginning: She would sign no paper givin’ up Ireland to him till first he’d set her on the throne of England. And on the morning of the fourth day, wonderin’ about manny things, Tim got on his horse and rode away.

And he hadn’t rode many miles before it came to him like a flash that there was a good many diplomatic disadvantages in his situation along with the diplomatic advantages of it. “Suppose either wan of thim quanes should get the notion,” says he to himself, “that I’ve been makin’ love to the other wan, and each of thim after wanting the other’s head that way?” An’ he couldn’t deny to himself that, although he’d been careful not to commit himself to nothing much, yet at the same time he’d given both of thim a bit of encouragement. “I’m betwixt love and honor,” says Tim to himself, “and I’ve got to step aisy.” But the main point of honor with him was which wan of thim would herself he doing the most honorable thing for Ireland.

“They’re both of thim kind o’ foxy, too thim quanes,” says Tim to himself. ’Twas running through Tim’s mind ’twould be the better stroke of diplomacy if he could but get the promise of both of thim regardin’ Ireland before he handed another crown to either wan of thim.

If Ireland was out of the question he’d have married Mary in a minute, and be damned to Elizabeth, as annywan would. But thinkin’ how much him and Mary was in love with each other made him sorry for Elizabeth, too, and the more he thought of it the more he pitied her, and he says to himself he’ll have to be extra kind to her when he sees her, to make up to her for what she don’t know about, and ’tis just this kind of tinder-heartedness that kept me in trouble all through me youth.

And ’twas thus he was revolvin’ love and diplomacy around in his head when he rode into London early one mornin’ and sent word in to Queen Elizabeth to get out of bed and slip somethin’ on; he wanted to speak with her at wance.

“And how is Scotland, Timothy?” says Quane Elizabeth, sittin’ on the side of her bed with a cup of morning tay in her hand, flappin’ a pair of blue mules on her feet.

“’Tis still there,” says Tim, diplomatic and noncommittal.

“I suppose you didn’t see that Mary Stuart, now, did ye?” asked the quane.

“I did get a glimpse of her,” says Tim, still tactful.

“Tell me, Timothy,” says the quane very confidential; “what does the woman really look like?”

“There’s but one woman in the known world, Elizabeth, who has any advantage on her in the way of looks,” says Timothy, seein’ that this was not wan of thim times when a diplomatist could afford to be entirely frank.

“And who may that woman be?” asks Elizabeth, cocking her intelligint eye at him over the top of the taycup.

“’Tis yourself,” says Timothy O’Meara, telling the most outrageous and audacious lie that ever left the lips of mortal man. But he pardoned himself, for ’twas for the sake of Ireland.

“You’re full of blarney,” says she, giving him her hand to kiss; but she was not ill pleased, at that.

“They do be sayin’ in Scotland,” says Tim, throwin’ out a feeler to see if any of her spies had been busy, “that she’s in mournin’ for a husband and planning to marry another wan.”

“Be damned to the woman!” says Elizabeth suddenly, throwing her cup and saucer against the wall. “I don’t like her! There’s manny reasons why I don’t like her, but one of the chief ones is she’s always gettin’ married! Marriage! Marriage! Marriage! What way is that for a quane to be conductin’ herself? ’Tis not dignified! ’Tis a kind of a reflection on all us Maiden Quanes. A quane ought to be far and away above all that matrimonial nonsense!”

For days he discoursed with Elizabeth and debated, but he could get no further with her than the wan word: “Make me quane of Scotland first, and after that Ireland’s free,” and on top of that she was forever urging him to enter into wan of thim formal engagements she was so fond of. Back he rides to Edinburgh, and ’twas similar with Mary. “Make me quane of England first,” she says, “and I’ll see that Ireland’s no more bothered”; and on top of that she was continually suggestin’ matrimony. And afther half a dozen of thim trips, commutin’ back and forth, Tim says to himself: “I’m spendin’ me life on horseback, but I’m not gettin’ annywheres!”

And then wan day the inspiration come to him that if he could get the two of them near together and let aich wan of them get the idea he was maybe getting a little interested in the other, the jealousy arisin’ out of that would lead to both of them offerin’ better terms for Ireland, for the sake of holdin’ onto himself. So he says to Elizabeth that he’s concocted a scheme that will give her Scotland without great warfare, but there’s a conference between her and Mary necessary first. And he speaks similar to Mary.

And ’twas thus he arranged the most extraordinary meeting of royalties and nobilities for the purpose of negotiations the world has ever seen. Quane Elizabeth comes north with twinty thousand men, in pride and splendor, and pitches her tent in a valley in the Cheviot Hills, and Quane Mary comes south with twinty thousand men and camps on the other side of the valley, and Timothy, who was to be president of the conferences, seats himself on a mountain overlooking both of them.

And both them quanes brings all their courts and all their counselors and earls and dukes, and their ladies with them, and the tents and pavilions was all of silk and cloth of gold and there was feastin’ and frolickin’ and tournaments and dances and sports, and the blowin’ of trumpets and the squeal of pipes, and cannon boomin’ all day and all night long in royal salutes, and nobody but the two quanes and Timothy knew what ’twas all about, and only Timothy knew the rights of it, for ’twas long before anny of this nonsinse about open diplomacy began to be chattered about the world.

Tim, he wasn’t in no hurry, and the feastin’ and the parties went on and on for weeks before the negotiations started; and the word that there was something momentous doing in England spread all over Europe. And King Philip of Spain marches in wan day off his ships with ten thousand troops, and tells Elizabeth he’s with her through thick and thin, and then takes the same word to Mary. And the next day there’s a burst of French horns, and the Juke of Alencon arrives with ten thousand men and says his brother, the king of France, would like to be reprisented too. And the Emperor of Austria and the Czar of Russia and the King of Prussia was the next that come troopin’ over the hills with their drums beatin’ and their banners flyin’. And with every fresh arrival there’d be a shout from all that soldiery and the thunderin’ clangor of ten thousand bung starters beatin’ on casks as more wine was opened, and the smell of the barbecued oxen was wafted across the wathers as far as Norway and Sweden, and all thim Scandinavian kings and nobility sniffed it and came along too. And Tim O’Meara sat on the top of his mountain and looked down on the valleys round about him and rubbed his hands and he says, “By the saints,” says he, “I believe I’ve started something!”

Ye talk about diplomacy! Never was there so much of it gathered together in wan spot, before nor since. And ’twas Timothy O’Meara was the man that had the key to it all. Everywan could see that he was in the confidence of both of thim quanes, though nobody but himself knew to what extent, and everybody courted him.

“Mr. O’Meara,” says the Duke of Alencon to him wan day, “ye could do worse for yourself than be commander in chief of the armies of France, under command of an enterprisin’ young king like mesilf. And if ye’d arrange a marriage betwixt the Maiden Queen and me, that’s what I’d make ye.”

“But ’tis your brother is King of France,” says Timothy.

“He’s not feelin’ so well these days,” says the duke, twistin’ his mustache to hide a smile, “and the bettin’ is three to wan he won’t live out the year.”

“Mr. O’Meara,” says the King of Spain, “I’ve been engaged to Quane Elizabeth, off and on, for three years, but still she dodges the altar. The day you get her there for me Mexico is your own.”

“I’ll think it over, Philip, me lad,” says The O’Meara.

And ’twas much the same with all of them kings and princes. Some of them wanted wan quane, and some of them the other, some of them this and some of them that, and sooner or later every wan of thim came to Tim. And thim two quanes kept him busier and busier. As yet, they hadn’t met each other, but their jealousies was runnin’ higher day by day, and aven hour by hour.

And the diplomacy kept gettin’ thicker and thicker and thicker, with more and more of them monarchs puttin’ their plans and combinations up to him, until he was himself, in his wan person, the repository for all the statecraft of Europe. And what with all that buzzin’ in his head, and breakfast with Elizabeth, and lunch with Mary, and a drink or two with Spain and Austria, and tay with Elizabeth, and a drink or two with Norway and Sweden, and dinner with Mary, and card parties and dances, and late suppers with both thim quanes, and constant and continual love-makin’, and new plans for Ireland formin’ every day, the thoughts in Timothy O’Meara’s head was whirlin’ faster and faster.

Faster and faster spun the diplomacy, round and round, inside of him and outside, but no matter how fast it spun he kept himself the master of it, and he said: “There’s wan thing that must not be! This diplomacy must not sink annywheres to the level of vulgar intrigue.”

And then things took a turn that began to make him a little uneasy. Each of them quanes got the notion at the same time she ought to be provin’ to him how he had the first place in her affections.

“Timothy, darlint,” Mary would say to him, “why did ye not drop in to tay yesterday? I had the Duke of Hamilton executed just to please yourself, thinking maybe you’d heard the false rumor that he was to be married to me. Ye’re neglectin’ me, Tim; ye don’t love me like ye did!”

“Mavourneen,” Tim would say, “it’s me that am plannin’ statecraft for ye day and night, and ye say that to me!”

“And when will these conferences begin?” says she. “And when am I going to be quane of England?”

“Lave the diplomacy of it to me, darlint,” says Tim.

And he’d be getting notes from Elizabeth that said: “Timothy dear, ye’ve been absent from me nearly twinty-four hours, and ’tis well I know politics is not all ye’re talkin’ to Mary Stuart these days. I’ve planned a party for your especial benefit tomorrow evening, and ye must not fail me. The Earl of Essex will be beheaded — him that was wance engaged to me — and afther that there will be dancing.”

Tuesday it would be Essex to the block, and Wednesday it would be her old favorite, the Earl of Leicester, and Thursday it would be Sir Walter Raleigh. And Quane Mary runnin’ through the Scotch nobility in the same way, beginnin’ to work out of the earls in the Lowlands up through thim chiefs of the Highland clans.

For a while these executions was no great moment to Timothy in thimselves; he took thim philosophical, saying to himself: “There’s another Englishman gone, and that’s that,” or, “There’s another Scotchman!” For the most of thim were no friends of Ireland. But as it went on and on he began to wonder if ’twasn’t a bad habit thim two quanes was formin’ for thimselves, and a habit that might lead to dangerous consequences for himself in the long run. The date set for that conference betwixt the two quanes, and their first meetin’ with each other, was comin’ nearer and nearer, and the nearer it came the less aisy was it for Timothy to know exactly what was the best thing to do with all thim diplomatic situations he’d made himself the master of.

’Twas on the day before the wan the conference was set for that Elizabeth said to him:

“Timothy, me love, I’ve got joyous news for ye.”

They were sitting in her royal pavilion, and Tim was getting a bit unaisy, for ’twas in his mind that he was overdue on the other side of the valley at Mary’s encampment.

“What’s the news, Elizabeth, me life?” says Tim, kissin’ her tenderly on the back of her neck and thinkin’ of Mary all the time. And terrible sorry he felt for Elizabeth, too, and that was the occasion of his tenderness.

“’Tis just this, Timothy,” says she: “I’ve decided to break me lifelong rule against matrimony — for wance annyhow and marry ye!”

And with that she slipped a diamond ring onto his finger. Tim, the poor divil, he didn’t dare to show his face for a minute, so he grabbed hold of her and squeezed her, and hung his countenance over her shoulder.

And pretty soon she says: “Ye don’t say annything, Timothy.”

“I’m speechless,” says Tim — “speechless with delight.” And then he says: “’Twill be just as well to keep it secret for a few days, darlint, till we get some of these diplomatic matters settled.”

And he got away from there as quick as ’twas decently possible, for he wanted to think over all the implications and complications of this new matter. If he was to be king consort of England he could rule that country and assure Ireland a square deal, but his heart was sore in him at the thought of Mary Stuart and giving her up like that.

And he stepped into the long tent where the lads in their white jackets was busy, and put his foot on the brass rail, for ’twas there the royal boys hung out of an afternoon; and he called for a glass of usquebaugh with a drop of bitters in it.

“Ye look sad, Tim,” says Philip of Spain, edgin’ over toward him. “What’s eatin’ ye?”

“Ain’t women the divil, Philip?” says Tim, diplomatic and noncommittal.

“More especially thim red-headed wans,” says the Duke of Alencon, tactless and partially inebriated. And the Czar of Russia, who was wan of thim Asiatic savages with knowledge of no European language, so that he had to do his drinkin’ through an interpreter, came over and declared himself in. And in a minute there was a dozen of them clustered around Tim at the kings’ end of the bar, and the mere dukes and earls down at the other end was edgin’ up as near as etiquette would sanction, with their ears open.

And wan thing led to another, what with the latest anecdotes and everybody wantin’ to buy, until inside of an hour there was less discretion among thim than ye would think possible in the case of such seasoned diplomats. And as for Tim himself, the poor lad, inside of him was wan big heartbreak at the thought of losin’ Mary Stuart, and it kept getting worse and worse the more he tried to drown it; and yet, on top of everything there was swimmin’ the thought that maybe ’twould be the best thing for Ireland did he become king of England and protect her.

“What’s the jam ye’re in, Timothy, me boy?” says Alengon. “Ye know damned well that I’m with youse, money, troops or annything else.”

“I know ye are, juke,” says Tim, “but ’tis wan of thim cases where nayther money nor troops will suffice.” And he sighed.

“’Tis women,” says the King of Norway. And the King of Prussia nodded sympathetic, and they all had another wan.

“None of us would mention no names,” says the King of Spain.

“Of course not,” says Tim. “Ye’re all gintlemen, aven if ye are kings.”

And pretty soon Philip of Spain led him aside and says: “Tim, give me the lowdown. What’s due to break, in the way of diplomacy? Don’t let me be caught unawares, Timothy.”

“Things looks bad, Phil,” says Tim, speakin’ out of his heartbreak rather than his diplomacy.

“If hell pops annywheres, slip me the word quick, and I’ll know what to do,” says Philip. “I’ll take no risks. I’ll turn me guns onto the Frinch at wance. These peace conferences is always dangerous.”

“I’ll do that same,” says Tim. And wan after another, every monarch present led him aside private and put substantially the same question to him, and got the same answer. “If hell pops,” says Alengon, “I’ll cut loose on the right flank of the English at wance.” And so on, each naming his favorite enemy; and then they all went back to drinking with one another, the same as these modern peace conferences, and Tim sighed and went to see Mary.

Her being a female and feminine woman, it was natural the first thing she would notice would be the diamond ring on Tim’s finger.

“Oh, Timothy, darlin’,” she cries out, slippin’ it off before he had time to resist her, “’tis the first thing ye ever gave me!” And with that she put her arms around him. “It’s sweet, it is!” she says. “’Tis my engagement ring.”

“Mary, me love,” says Timothy, “’twas me own mother’s wedding ring” — and he was about to say that for that reason he couldn’t give it to anyone, not aven to her, but before he could get that far with it, Mary says, says she: “Oh, Timothy, that makes it all the sweeter.”

So Tim thinks to himself that he will get it away from her again pretty soon with some pretext or another. But talking about this, that, or the other thing, political and personal, it clean slipped away from his mind, and when he left there late that night it was still out of his mind. The trouble was there was so many political complications in Tim’s mind at this time that he had very little room there for anything else, and with both of them girls he had most desperately tried to postpone this conference that was coming tomorrow until he should get the opportunity to meditate more profoundly on the situation. But nayther one of them was willing for any more postponement. Each one of them wanted that other crown as soon as possible and each one of them wanted Tim united with her in the holy bonds of matrimony.

And the next afternoon Tim sat alone at the table in the conference tent before ayther one of thim arrived, with considerable apprehension on the inside of him. One of thim came in through one door and one of them came in through the other, and both of thim had their crowns on, and aich of thim had a tea-party smile on her face, but what was underneath that smile Timothy trembled to think of.

They bowed formal to each other, with that smile, and Elizabeth was the first to speak. “You’re Mary Stuart,” says she.

“And you’re Elizabeth Tudor,” says the other wan. “I’ve often heard Mr. O’Meara speak of ye.”

“Girls,” says Tim, “sit down. And we’ll be getting on with our statecraft.”

But, as ill luck would have it, the first thing that Elizabeth noticed was that ring. “Statecraft be damned!” she cried out, pointing to it. “Mary Stuart, where did ye get that diamond ye’re wearin’?” “’Tis wan of the crown jewels of Scotland,” says Mary. “Ye lie!” says Elizabeth. Mary drew herself up proud and regal.

“Ye speak to me like the daughter of Anne Boleyn, that everywan knows was never married legal to your father, the king.”

“Ye answer me like David Rizzio’s mistress,” says Elizabeth, “that everywan knows was wance married legal to me Cousin Darnley.” And with that they stood and looked at aich other in such a way as ye could feel the silk walls of that tent crackin’ and snappin’ with electricity, whilst they themselves turned every color of the rainbow.

“Now then, ladies “Tim says.

But they both turned on him. “As for you, Tim O’Meara “says Elizabeth, and choked with rage. “As for you ⎯ “says Mary. ’Twas in that instant that the red hair of Tim O’Meara began to show streaks of gray. And slowly they turned back toward each other.

And ’twas then that Timothy O’Meara caught the sudden inspiration which was wan of the greatest strokes of diplomacy the world has ever seen. With thitn two redheaded queens still locked in that terrible look, each strugglin’ for the word that would say her feelin’s, Tim backed quietly out of that tent and in a minute was standing at the door of the barroom.

“Boys,” he cried out to all them royalties and notabilities, “hell has popped!”

Startled, they dropped their glasses, and as they turned their faces toward him the thing he saw plainest and always remembered was twenty pairs of eyes sticking out like the eyes of snails.

“Hell’s popped!” he says again, and was out of there and took his way to his mountain. And he was scarcely there before he heard the drums beatin’ and the trumpets blowin’, and in a minute more the rattle and crash of musketry, and then began the roar of cannon. And in all the valleys and slopes beneath him there was the flash of steel and rollin’ billows of fire and the reek of smoke and the shoutin’ of men and the thunder of hoof beats. “The world’s at war,” says Tim — “all but Ireland!”

And for three days he set on his mountain, lookin’ down upon that strife, while reenforcements swarmed in from all sides, from all over the world, thinkin’ to himself with every charge and every volley that there went another hundred foreigners who would never trouble the freedom of Ireland. For ’twas the crown and glory of his great stroke of diplomacy that while the rest of the earth was at war and too busy to think of Ireland, out of that turmoil he would snatch the freedom of his native land.

And on the fourth day he took his way back home with the news that Ireland was free. And whilst he was organizing a stable government there, he died in camp. But before he died he got a note from Elizabeth in which she said: “Timothy, I have conquered Scotland and am now queen of the same, and I would sind ye the red head of that Mary Stuart by this same messenger, if I did not know that ye are more interested in auburn hair like me own than in plain red. A great manny of me counselors are urging me, now that Scotland and Mary Stuart are out of me way, to go after Ireland and Tim O’Meara, and go afther thim hard. But old frindships is not so easy forgot as all that, and if it was in your mind to come over to London and visit the Maiden Quane, I have no doubt that somethin’ could be fixed up satisfactory to England, Ireland, yoursilf and me. Think it over, Timothy, me dear.”

And Timothy wrote an answer in which hesays: “My dear Elizabeth, Ireland and me will stay whare we are.” And the shame and sorrow of it all was that with his death the fruits of all his diplomacy was dissipated because his successors was lunkheads, and the Sassenach came back again with fire and sword.

But there’s nothin’ can take away the fame of his merits, and if I ever hear either wan of you whisperin’ again that Ireland never had a diplomatist, I’ll take bothav youse acrost me knees and larrup ye well, as I am still able to do, praise God!

Illustrations by Tony Sarg, © Copyright The Saturday Evening Post

Cancelling Satellite Radio: Siriusly Painful

Attempting to get out of a relationship with a subscription service these days often requires chatting with a robot designed to thwart your intentions either by talking you out of quitting or by upselling you to a more premium product. What follows is a lightly edited transcript of a chat that took up the better part of an hour with the maddeningly polite “Jointy” at SiriusXM.

Jointy: Hi, my name is Jointy. Thank you for contacting SiriusXM. I hope you’re healthy & fine.

You: I want to cancel please.

Jointy: That’s unfortunate to hear that you are considering cancellation. May I know the reason of cancellation to serve you better?

You: I’m not ‘considering’ canceling. I am cancelling. My car lease is ending.

LONG PAUSE

Jointy: May I know when exactly the lease is ending?

You: I’d rather not say. Let’s make this easy and skip all the questions.

Jointy: Do you have any vehicle active with Trial?

You: I don’t know what you mean by Trial.

Jointy: Let me check the Account. Do you have any plan to buy vehicle in near future?

You: No.

LONG PAUSE

Jointy: If you have any plan in near future then I have some exciting offers for you.

You: I just want to cancel please.

Jointy: Should I process the cancellation of subscription now or on the next renewal date?

You: Now.

VERY LONG PAUSE

Jointy: Okay.

LONG PAUSE

You: Are we done?

Jointy: I’m working on it. While proceeding to cancellation, I see your Account is eligible for the Essential Streaming so that you can listen online on your mobile, computer, Alexa, Google device, tablet, etc as Streaming is independent of the Radio. So let me cancel the Radio and activate Essential Streaming.

You: Sure, if there’s no fee.

Jointy: No problem.

LONG PAUSE

You: This is taking a long time. I have dinner plans. Are we done?

Jointy: I’m processing the cancellation.

LONG PAUSE

You: Do I need to standby? Or can I disconnect?

LONG PAUSE

Jointy: Today I cancelled your service. You have a remaining credit of $9.02 which may be used for other transactions today, or in the future. Any remaining balance may be refunded to you upon request.

You: I’d like to ask that it be refunded.

Jointy: A confirmation of this transaction will be sent to the email address on file, for your account within 5 days. I will be happy to process refund for you.

You: Thank you!

Featured image: Ico Maker / Shutterstock

Eugene Field Helped Craft America’s Sense of Humor, Then We Forgot Him

When Eugene Field died in 1895 at age 45, fellow authors and friends hastened to share their fond memories of the humorist and poet. He was a hilarious prankster and a heavy drinker with an impressive book collection, but, most of all, he was a loyal friend.

Field was born 170 years ago on September 2, 1850, although he reportedly told people his birthday was September 3rd if they were late to wish him a happy birthday, just so they wouldn’t feel too bad about it.

Even though more than 30 elementary schools around the country have been named after the prolific writer, his literary renown has scarcely held up to the household-name status he enjoyed during his life. As a poet, he crafted the most popular children’s poems and lullabies of the era, including “Little Boy Blue,” “Wynken, Blynken, and Nod,” and “The Sugar-Plum Tree,” all of which were published in this magazine or its affiliated children’s magazines. As a newspaperman, Field garnered a national following for his witty columns documenting people and the arts, first in Missouri, then in Denver, and finally at the Chicago Daily News.

His column “Sharps and Flats” ran in the latter paper six days a week for the last 12 years of his life. By at least one account, he was the most popular columnist in the country during that time. Of a young Rudyard Kipling, Field wrote that “he has been flattered to an amazing degree since he woke up one morning and found himself famous” and that “there may be … twenty newspaper reporters in New York City capable of doing as good work as Mr. Kipling has done; at the same time, they have not done it and Mr. Kipling has.” Field gushed over a World’s Fair exhibit on Hans Christian Andersen, writing of “that dear heart which beat in unison with the simplicity, the truth, the candor, the enthusiasm, the wisdom, and the pathos of childhood!”

Field was also known for his scathing and sardonic quips on politicians of the day. In 1883, he wrote, “Grover Cleveland seems to have suddenly and completely dropped out of sight. Perhaps he is rehearsing Santa Claus for a Sunday-school celebration next Christmas. These politicians are queer people.” Writing for the Denver Tribune, he offered whimsical advice for all children aspiring to go into politics: “If you neglect your education and learn to chew plug tobacco, maybe you will be a statesman some time. Some statesmen go to Congress and some go to jail. But it is the same thing, after all.” One can imagine that Field would have found no shortage of bon mots to pen on the Progressive Era of American politics, had he lived to see it.

A few years after his death, Francis Wilson memorialized the writer in a biography published in this magazine as “The Eugene Field I Knew,” writing, “Field’s mind and heart were wide open to the sunshine of humor and the joy of laughter.” Sometimes this candidness expressed itself in wild antics, as when Field reportedly pranked a posh Thanksgiving dinner party by exploding the turkey with a firecracker: “He wasn’t invited back.”

Field’s close friend George H. Yenowine wrote for the Post several years later on “The Serious Side of Eugene Field,” claiming he had received the former’s last written letter. Yenowine noted that Field wrote his correspondence in six different colors of ink, depending on the tone of a given letter. He was also known to spend hours embellishing the margins with drawings and designs. In his letter to Yenowine two days before his death, Field went on excitedly about many projects he was looking forward to, before finishing the missive with a characteristic confession: “Irving Way has been wanting me to do the preface to the volume of Anne Bradstreet’s poems which the Duodecimo will publish; but Anne is a tough, uncongenial old bird, and I hesitate to tackle her. I suppose that one is justified in putting off a task he feels he cannot do well.”

Although Field’s prominence in the American literary canon has waned, his influential effect on humorists into the 20th century, such as John T. McCutcheon, Mark Twain, and even — tangentially — Molly Ivins, is undeniable. Don Marquis professed that he read “Sharps and Flats” every day. In his 2001 biography, Eugene Field and His Age, author Lewis O. Saum claims that Field created the newspaper column, and yet much of the writer’s work from the Chicago Daily News was lost forever: “We knew him very well for something like a half-century. Then, recalling little other than something labeled ‘calamitously sentimental,’ we averted our gaze.”

Field’s irreverent approach to constructing the record of the day can be remembered as a quaint, but formative, addition to the uniquely American voice; the oversized role he played in holding a mirror to the country and its politics at such a precarious time as the late 19th century has received a fraction of the attention it deserves.

Featured image: Buffalo Evening News, December 3, 1895

Wit’s End: Oh, Give Me A Home Where the Buffalo Roam

Recently, I ran across a phrase I’d never seen. It was in the title of a book by Utah-based survivalist Joel M. Skousen: Strategic Relocation: North American Guide to Safe Places. According to Amazon.com, the fourth edition of Strategic Relocation “considers future threats that most other people fail to see” — including natural disasters, pandemics, stock market crashes, and nuclear war — and highlights out-of-the-way places where one might ride out society’s collapse.

In what now seems like prescient timing, the paperback came out in January 2020.

My family has no immediate plans to strategically relocate. But after years of raging wildfires, power shortages, and rising costs of living, we’ve come to doubt that California is our forever home. As we mull our options, the phrase “strategically relocate” has a nice ring to it. It makes people fleeing, abandoning ship, making a run for it, and ghosting sound like they’re soldiers executing a brilliant military plan.

In fact, this year, absconding is on-trend. People are pouring out of San Francisco, New York, and other cities that are struggling after months of shutdown. As writer James Altucher observed, this is in part because “[b]usinesses have realized that they don’t need their employees at the office,” and high-speed bandwidth allows millions of desk jockeys to Zoom from home.

People who can work anywhere have shown a sudden hankering for country living. Instead of being three blocks from The Apple Store, a futuristic winter-white temple of tiny computers, they long to be “home on the range, where the deer and the antelope play.” Tired of being bombarded with words so discouraging they cannot be printed in a family magazine, they dream of a land of blue skies where “seldom is heard a discouraging word.”

The collective wish for greener pastures is even showing up on Instagram, where a style called “cottagecore” is a top trend of 2020. Photos show young women wearing hairstyles straight out of “Little House on the Prairie,” and clad in “flowy dresses, floral patterns, flower crowns, and vintage style hats,” as one article put it. Tranquil pursuits like baking and gardening abound, as if the student-loan-and-hookup generation has strategically relocated to a simpler time, when tinder was a bundle of sticks used to light a cast iron stove.

When you think about it, strategic relocation is about as American as it gets. Before the first European settlers showed up, nomadic tribes like the Blackfoot, Cheyenne, and Comanche strategically relocated to track buffalo across the great plains. In 1620, a group of English Puritans strategically relocated to a rock in what is now Massachusetts. After the Civil War, the descendants of enslaved people picked up and strategically relocated to wherever they hoped they could find a better life.

Over the centuries, waves of immigrants strategically relocated to our shores, including my maternal great-grandparents and my dad. Once you turn eighteen, strategic relocation is a way of life: first for college, later for jobs, and lastly when you commit a serious crime and need to leave to the country or fake your own death.

Even our literature is full of strategic relocators. At the end of The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, the teenaged hero decides to “light out for the Territory,” away from the civilizing influence of the Widow Douglas. (After an exciting journey down the Mississippi River with his friend Jim, life at home feels a bit too “cottagecore” for Huck.)

I’m well aware that, if I move, it will make for some awkward moments. Californians are the most disliked strategic relocators, always blowing into other states and acting like Angelina Jolie on the red carpet. We arrive with a long list of unreasonable demands: six dozen white roses (and a single blood-red rose) in our dressing room; bottled water that has been vibrated by the sound of a Tibetan gong and absorbed its healing frequencies; servants to take care of our dogs; a bunch of new, annoying rules we just made up.

But I plan to be the exception: a California transplant whom people don’t hate. I grew up in a small town where getting one’s own truck was a rite of passage. I know how to say hello to the old guys who meet every morning at the donut shop, and how to inquire after the bank teller’s kids. I will not try to make everyone do yoga or urge you to swap out your burgers for green smoothies.

If anyone asks where I relocated from, I’ll reply, strategically: “I’m just happy to be here.”

Featured image: Migrant family heading to the American West, 1886. (National Archives)

The Upside of Hypochondria