How to Look at a Norman Rockwell Picture: Part 5 — Light and Color

Read all of art critic David Apatoff’s columns here.

This is the fifth in a series of columns on how to appreciate the artistic side of Norman Rockwell’s paintings. See Part 1 on Rockwell’s use of hands, Part 2 on his use of black and white, Part 3 on how he leads your eye, and Part 4 on his interaction with the great artists in history.

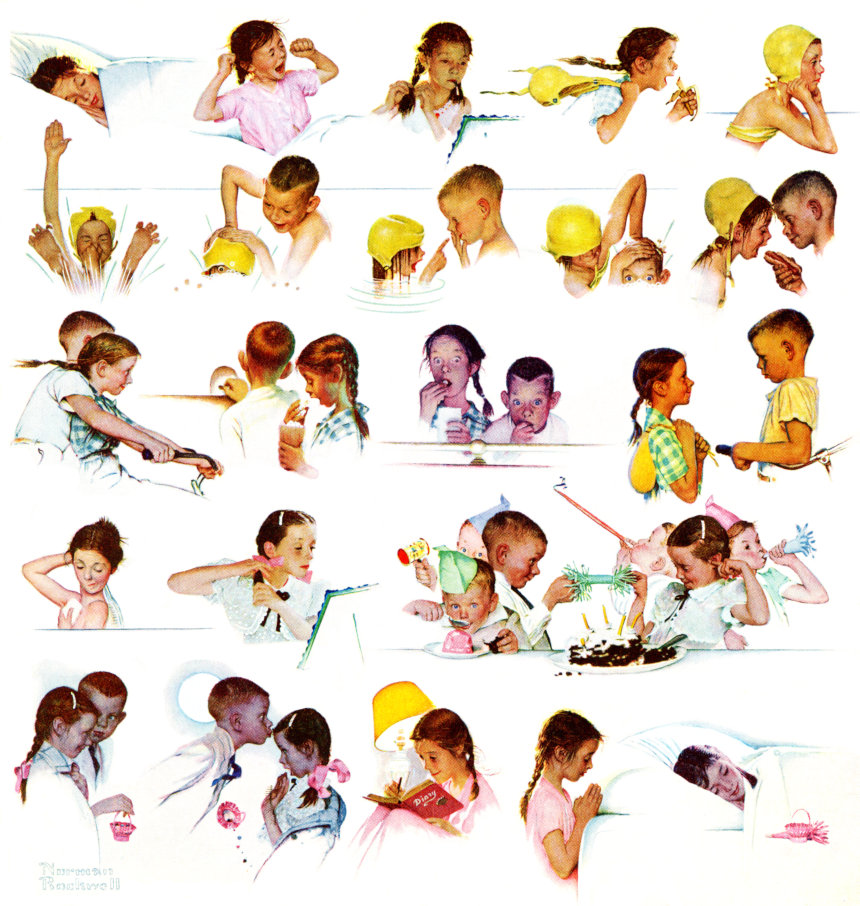

You couldn’t be blamed for thinking that this painting, entitled “A Day in the Life of a Girl” is about a day in the life of a girl.

But if you look closely there’s a second subject staring you right in the face: that subject is “light.”

Rockwell could easily have painted each event in the same consistent light. Instead, he spent a great deal of effort capturing light’s subtle changes throughout the day. Light is a separate character in this painting, as important as the girl.

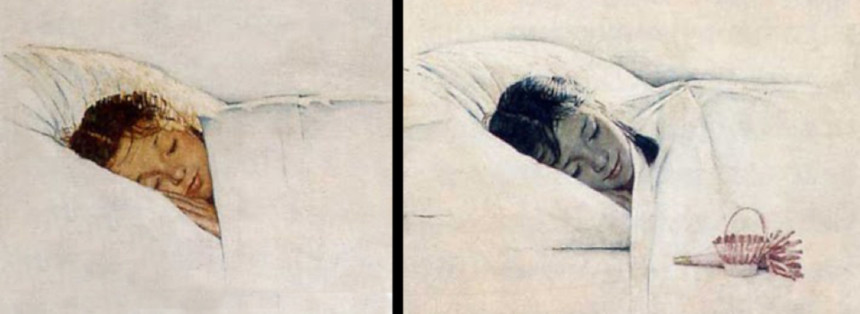

For example, compare the girl at the beginning and end of the day. Rockwell saw that the morning sun illuminates the full range of color in her skin and hair, with emphasis on warm colors such as red, orange and yellow. Moonlight, on the other hand, diminishes the color spectrum and creates cool colors such as blue and gray.

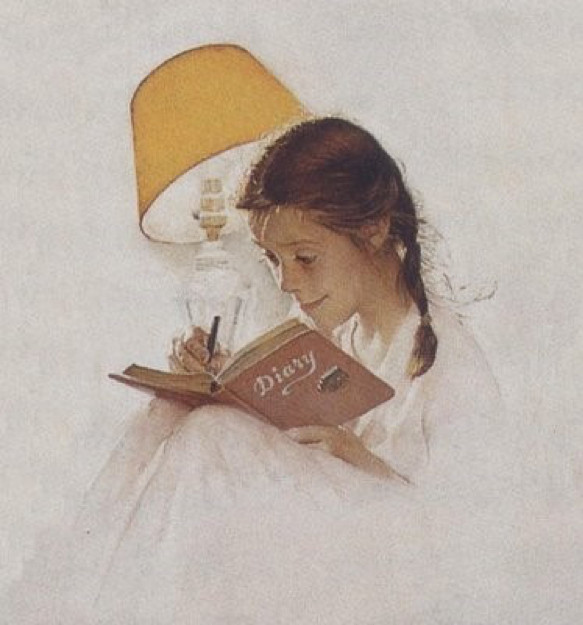

Next, notice how Rockwell captures the way artificial light from a bedside lamp looks different from natural light:

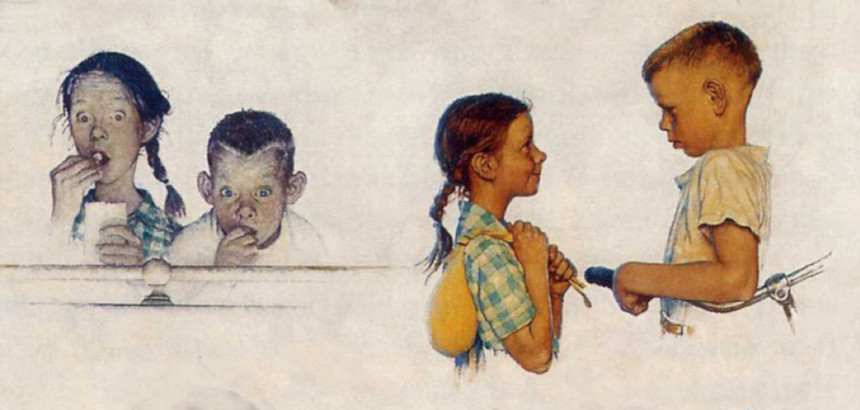

And electric light from the bedside lamp looks very different from the electric light of a movie theater marquee (below):

The sharp-eyed Rockwell can even distinguish between two different kinds of theater lighting: he paints the light from the marquee (above) differently from the way he paints the light from the silver screen (below). Then, after the movie ends and the children step out into the golden glow of the late afternoon sun, the light transforms their color completely:

Painting the effects of light required as much artistic skill and observation as painting the girl. This brilliant painting could just as well be called, “A day in the life of light.”

Artists have always been inspired by light; it is the magic ingredient, the source of what we perceive as color. Rockwell may have been a commercial illustrator who painted entertaining magazine covers for a corporate employer, but he was simultaneously a gifted artist, solidly within the artistic tradition that regards light as a source of wonder. (In a previous column I compared Rockwell to the famous impressionist Monet, who painted the same haystack several times to show that color looks different at different hours of the day.)

If you want to appreciate the artistic side of Rockwell’s work, look for the ways in which his paintings celebrate the qualities of light.

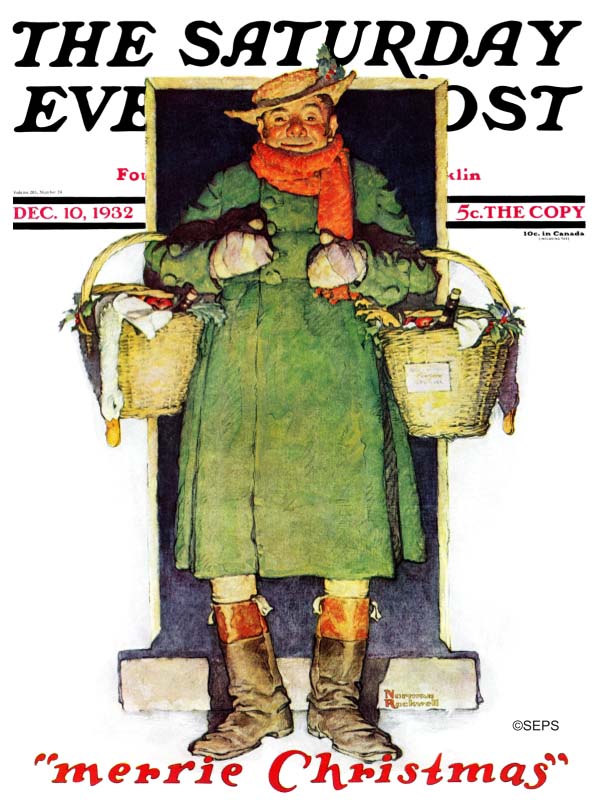

For example, why does the lighting of this fellow in the doorway look so warm and welcoming?

The source of light is from the ground up, rather than from the normal top down. Also, the light has an unusual warm glow. This is because the light is coming from a crackling fire in a fireplace. Rockwell doesn’t need to paint the fireplace for us, he can imply a fireplace using light.

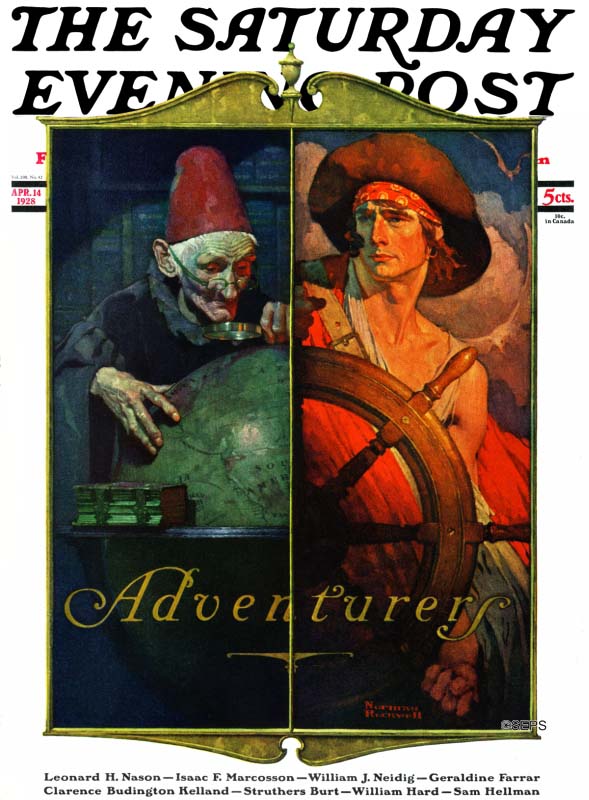

In the next example, Rockwell uses color to contrast an ancient scholar at night in his study with a bold young explorer sailing into the dawn.

Rockwell didn’t have to clutter up his painting by showing additional objects, such as a black sky with stars and a moon, in order to set the scene. He was able to explain to viewers that it is night because he understood the palette of moonlight.

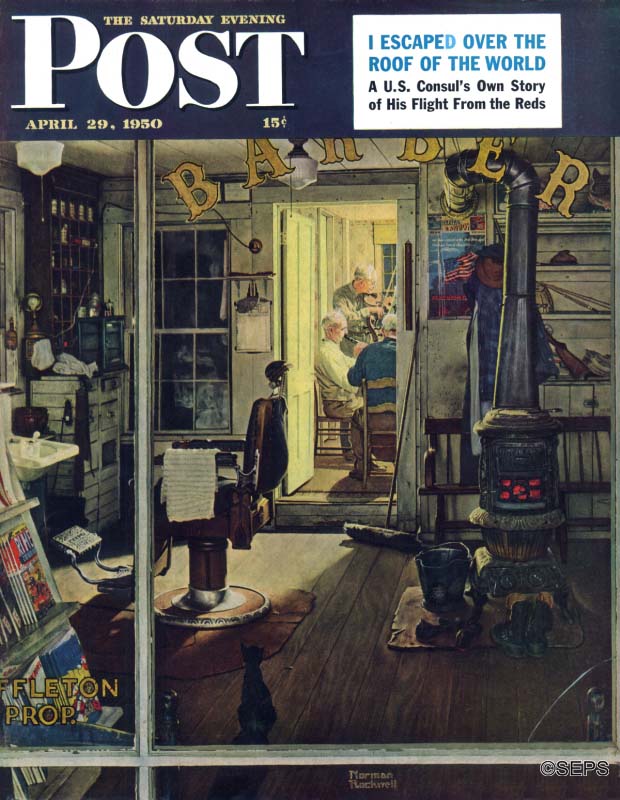

Finally, it’s important to emphasize that the artistic role of light goes beyond having the keen eye and technical skill to reproduce shades of light accurately. Light can also play a major emotional and psychological role in art. For example, look at Rockwell’s Post cover of a group of amateur musicians playing together after hours in the back of a barbershop:

Why didn’t Rockwell paint the entire scene in a well-lit room so he would have more space to show all those warm, folksy details and facial expressions for which he was famous?

The answer is that it was psychologically more effective to use a narrow sliver of light to reveal a partial glimpse of the beating heart of the picture. The joy of this picture is that these musicians are playing for their own private pleasure, not performing publicly. Their shining time together is surrounded on all sides by the darkened place of business, which makes this a more powerful, emotionally moving painting.

All this was achieved with color — one more example of how the mastery of light made Rockwell an excellent artist.

Featured image: Norman Rockwell/SEPS.

Considering History: Remembering the Founding Fathers, Flaws and All, on the Fourth of July

This series by American studies professor Ben Railton explores the connections between America’s past and present.

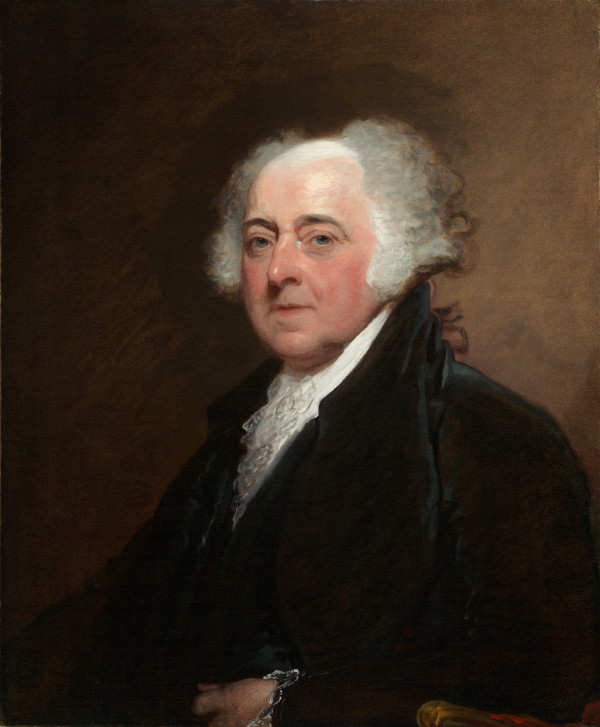

On July 4, 1826, John Adams and Thomas Jefferson, America’s second and third presidents and two of the most famous and influential founding fathers, passed away within a few hours of each other. More than just a striking historical fact and one final interconnection between two friends and rivals whose lives and careers had often intertwined, Adams and Jefferson’s July 4 deaths offer a succinct illustration of how much the founders had already become, half a century after the Declaration of Independence, mythic figures with larger-than-life identities and stories.

Those myths are not without merit: the Declaration, Revolution, and Constitution were bold and impressive achievements, and a core group of figures played significant roles in all of them. As I argued in last year’s July 4 article, however, the Declaration also contains a hidden history that reflects darker and more divisive Revolutionary realities of slavery and hypocrisy. Similarly, founders like Adams and Jefferson were complex men, multi-layered historical figures whose flaws as well as their successes have a great deal to teach us about their period and America.

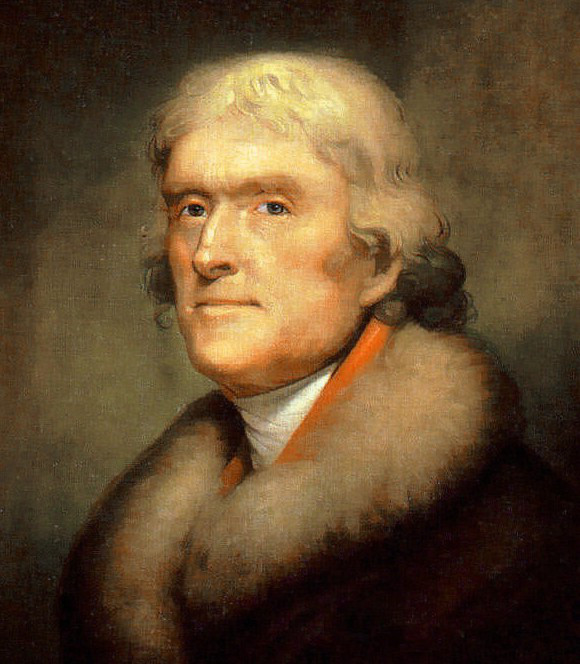

Jefferson’s worst failings are well known, and indeed have come to be defining aspects of our collective memories of him. Yet those flaws go deeper than the alleged (and historically likely, per both uncovered DNA evidence and the vital work of scholar Annette Gordon-Reed) repeated sexual assaults on one of his slaves, Sally Hemings. They also entail racist views of African Americans that become even more hypocritical when seen in light of those personal actions — views illustrated by the cut Declaration paragraph on slavery and the “foreign people” it had “obtruded upon” the colonists, but developed at much greater length in his Notes on the State of Virginia (1785).

In one especially striking extended passage from Notes, Jefferson expounds at length on all the factors that make “the blacks … inferior to the whites in the endowments both of body and mind.” He remarks upon their “very strong and disagreeable odor,” their “want of forethought” and “transient griefs,” and their imaginations that are “dull, tasteless, and anomalous.” And he concludes, with particular hypocrisy for a lifelong slaveowner, that “This unfortunate difference of color, and perhaps of faculty, is a powerful obstacle to the emancipation of these people.” While that “perhaps of faculty” indicates an attempt at scientific nuance, the passage as a whole reflects a man unable or unwilling to learn the human truths of the enslaved African Americans all around him.

When it comes to John Adams’s flaws, there’s a general sense that he was one of the most elitist of the founders, a die-hard Federalist who at times feared the general public and its potential for disorder and sedition more than he sought to protect them in our framing documents. That’s a simplified but not inaccurate description of Adams’s overall political philosophies, yet I would argue that it hides a deeper flaw: as his impassioned legal defense of the British soldiers accused of murder at the 1770 Boston Massacre reveals, Adams’s elitism was also racially and culturally charged.

Defending the soldiers was Adams’s job as a young Boston lawyer, and one that he performed with fervor, particularly in an eloquent court monologue that helped win an acquittal for many of the accused. In the course of that statement, Adams deployed a series of stereotypical and bigoted images of the massacre’s first victim, Crispus Attucks. Attucks, Adams argued, had “undertaken to be the hero of the night” through his “mad behavior,” but exemplified instead the event’s “motley rabble of saucy boys, negroes and mulattos, Irish teagues and outlandish jack tars.” Given that Attucks was not only a mixed-race individual but also a fugitive slave, Adams’s language reveals the links between Revolutionary elitism and the same kinds of racist hypocrisy embodied by Jefferson.

So these famous founders weren’t just flawed — they were flawed in ways that reveal some of the exclusionary, white supremacist elements of the nation’s origins. Their vision of who was American — or at least who was most fully and definingly American—was certainly part of the Revolutionary era, and has continued to echo ever since. But it’s not the only side of the era, nor of these men and their lives and legacies. There are also genuinely inspiring sides to both Adams and Jefferson that embody our nation at its best.

Some of Adams’s most inspiring moments are directly tied to his marriage, and through them to his wife, the deeply impressive historical figure Abigail Smith Adams. Thanks to the work of historian Sara Georgini and the entire Adams Family Papers staff at the Massachusetts Historical Society, we have unparalleled access to materials like John Adams’s letters, many of which were exchanged with Abigail as the two were separated for more than a decade before, during, and after the events of the Revolution.

Those letters are justifiably famous for striking individual moments: John’s eerily accurate July 1776 predictions about future Independence Day celebrations; Abigail’s March 1776 letter imploring her husband and his fellow framers to “Remember the ladies” in their deliberations. But what the letters as a whole reveal more deeply are the sacrifices made by the founders during their decades of service to the nation for which they were fighting. That’s especially clear in an emotional July 1776 letter when John, having learned that his family had been suffering from smallpox without his knowledge, writes,

Do my Friends think that I have been a Politician so long as to have lost all feeling? Do they suppose I have forgotten my Wife and Children? … Or have they forgotten that you have a Husband and your Children a Father? What have I done, or omitted to do, that I should be thus forgotten and neglected in the most tender and affecting scene of my Life! Don’t mistake me, I don’t blame you. Your Time and Thoughts must have been wholly taken up, with your own and your Family’s situation and Necessities. But twenty other Persons might have informed me.

Thomas Jefferson had many important and influential moments throughout the Revolution as well as during its aftermath; he drafted the Declaration of Independence and served two terms as president. But to my mind it’s his philosophical, legal, and intellectual work over those same decades that offers his most inspiring contributions to that new America.

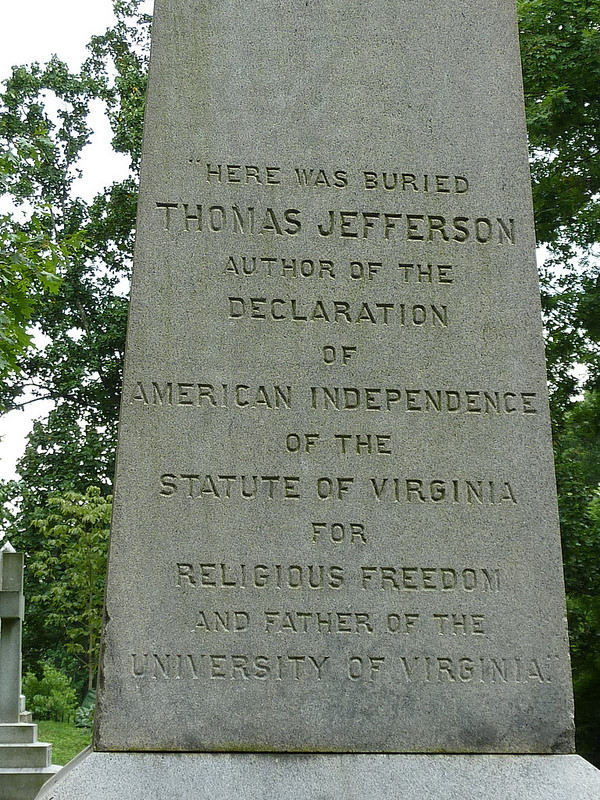

Exemplifying that vital work was Jefferson’s drafting of the 1786 Virginia Statute for Religious Freedom. This law, a key predecessor to the First Amendment’s protections of religious freedom, guaranteed that all Virginians “shall be free to profess, and by argument to maintain, their opinions in matters of religion, and that the same shall in no wise diminish, enlarge, or affect their civil capacities.” Jefferson put that philosophy in action through his professed support for Islam and Muslim Americans as part of these new civic communities. And a few decades later he created a community where such religious and intellectual freedom could flourish, founding the nation’s first non-sectarian public university, the University of Virginia, in 1819.

Jefferson wanted both the statute and the university memorialized on his tombstone (along with the Declaration), a moving illustration that as of July 4, 1826, such civic contributions remained critically important. The two towering figures who died that day left legacies that include some of America’s more divisive and bigoted histories to be sure. But they also contributed, through their lives and their ideas, to the founding of American ideals as well as the nation. Critical patriotism requires us to remember all these sides to Adams, Jefferson, and America on the Fourth of July.

Featured image: John Adams and Thomas Jefferson (Detail from postcard published by The Foundation Press, Inc., 1932. Reproduction of oil painting from the artist’s series: The Pageant of a Nation. Collection of the Virginia Historical Society, Library of Congress)

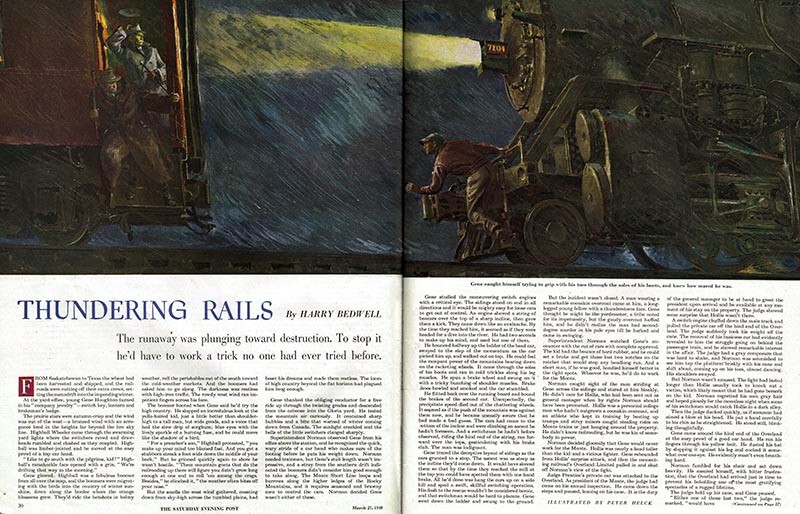

The Art of the Post: The Artist Who Loved Trains

Read all of art critic David Apatoff’s columns here.

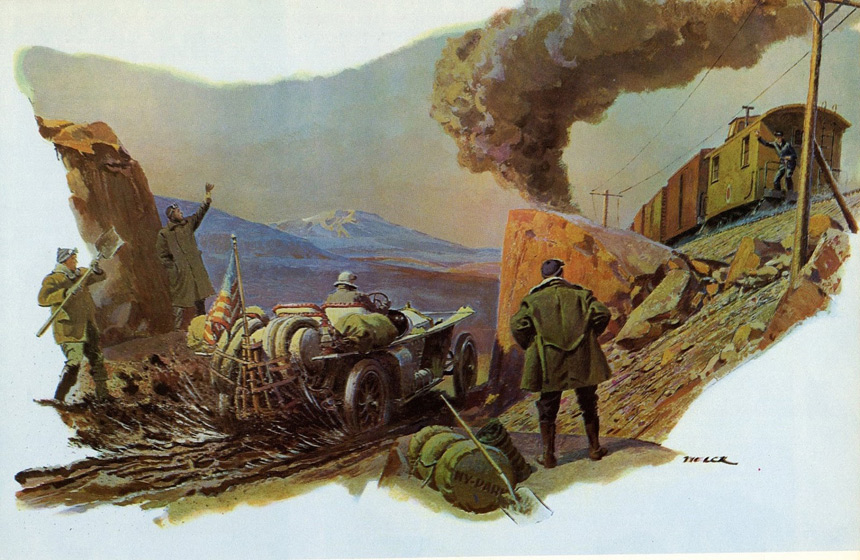

Some artists specialize in painting landscapes. Some focus on painting portraits. Peter Helck painted trains.

Helck found as much excitement and inspiration in trains as other artists found in love stories. An article about Helck in American Artist magazine said, “he paints [railroads] with authenticity and with a dramatic power which expresses the romantic appeal these things have for him. He is passionately fond of locomotives; they are frequent subjects of his canvases.” Helck put it more bluntly: “[I’ve been] wacky over steam locomotives all my life.”

Helck was born in New York City in 1893. By the time he was 10 years old, he was spending his allowance each week on the model trains at Coney Island. His first art jobs were working for the art departments of local stores. As his reputation grew, he graduated to illustrating for magazines such as The Saturday Evening Post. Publishers spotted his special talent for painting machinery and industrial equipment, so when an assignment called for a picture of machines such as trains or old cars, Helck became the first artist they called.

At age 30, Helck moved to a large farm in Boston Corners, about 100 miles north of New York City. On his farm he had room to store his growing collection of battered old cars and tractors. When he wasn’t painting, he enjoyed working on them in his barn.

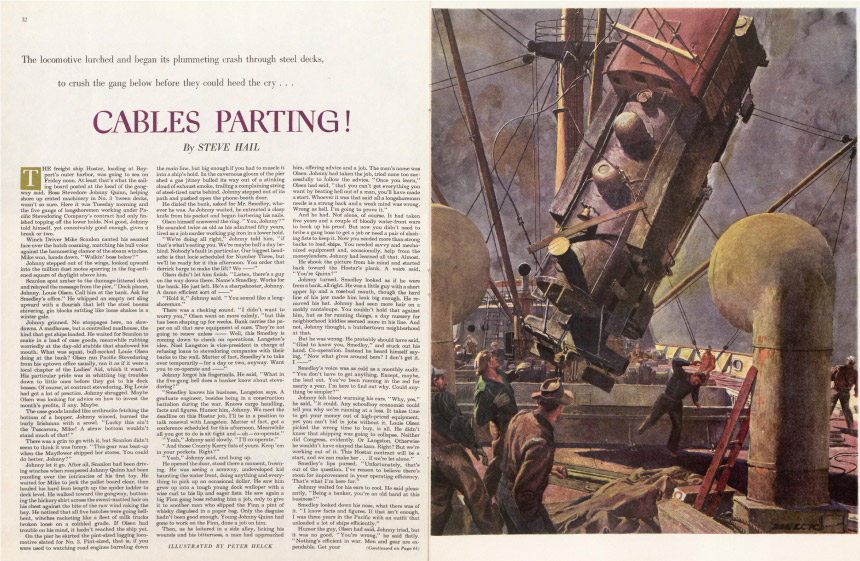

One of Helck’s favorite things about illustrating trains was that he occasionally wrangled permission to ride in the engine cab of real trains, sketching details and getting a sense for the experience. While illustrating the story “Thundering Rails” for the Post (March 27, 1948) Helck was able to ride in the engine cab of a train to Albany, New York.

He recalled breathlessly, “I got to work in an atmosphere gloriously dense with soot and smoke and generously affording the dramatic night lighting effects of which I never tire.” Of course, sometimes he forgot to ask permission. More than once he was kicked out of a train cab for trespassing.

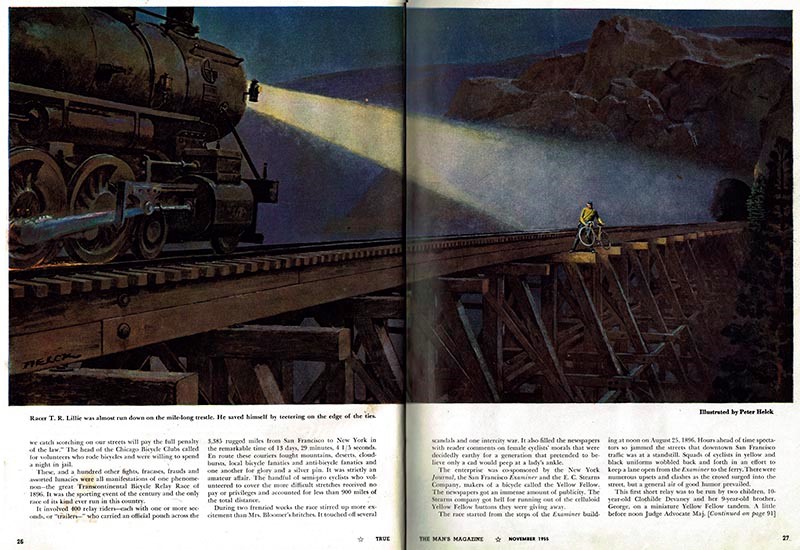

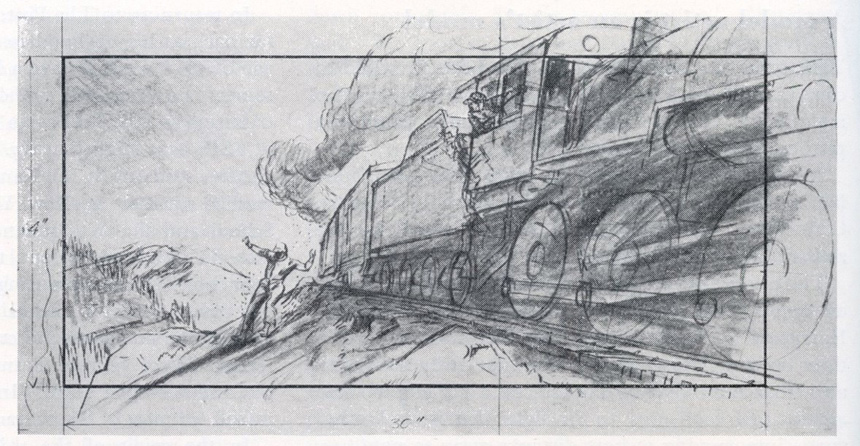

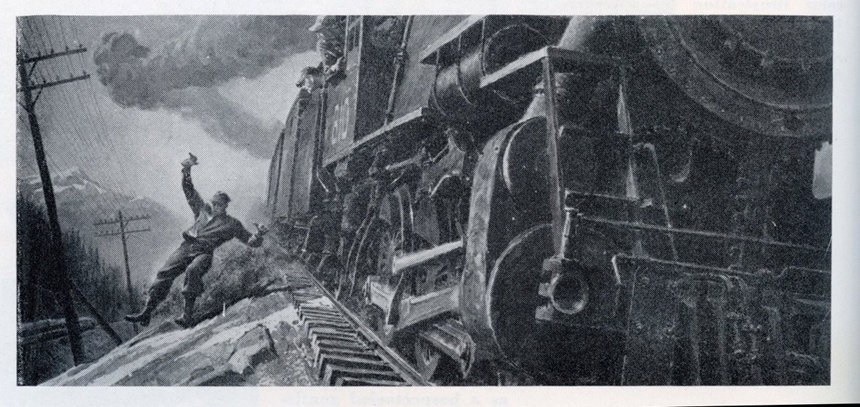

He also ran into trouble because he sometimes made the train, not the people, the star of his painting. As you can see from the following preliminary sketches for the story, “Screaming Wheels,” (The Saturday Evening Post, February 19, 1949) Helck started out by giving the starring role to the train, leaving a only a minor role for the human (who was supposed to be the center of the story).

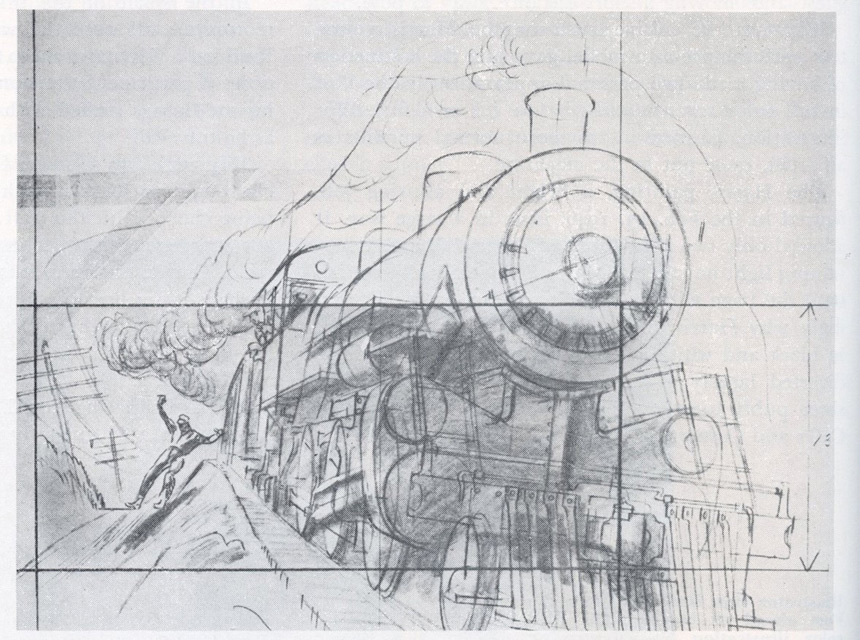

In the next drawing, Helck was nudged into increasing the importance of the man jumping off the train. Still, the train remained too prominent, so you can see how Helck cropped his beloved train to diminish its role even further.

Here is the final version as it appeared in The Post, with the train veering off to the side and the man in the central role.

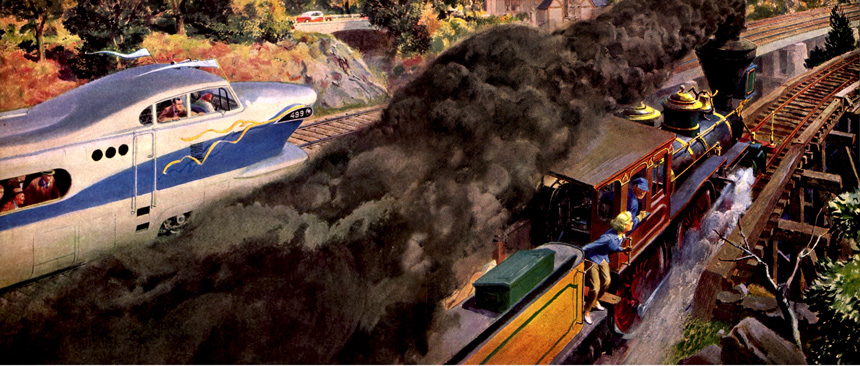

For another assignment, Helck painted a locomotive with smoke belching from the smokestack. When he delivered his finished painting, a junior account executive didn’t care for the dirty smoke, so he rejected the painting. He instructed Helck to take it back and paint a cleaner version minus all the smoke. However, when the art director saw the cleaner version, he was livid. He called Helck and asked him to restore the smoke, grumbling, “I was out of the office, sick, and that so-and-so went over my head. If I send it back will you put the guts in it again?”

Because Helck understood trains from top to bottom, he was even able to imagine how a falling locomotive would look. Obviously, no one could suspend a massive locomotive mid-air for Helck to paint, but he could project one in his mind. What other illustrator could pull off such a feat?

Most artistic traditions have been shaped over thousands of years. Artists in ancient Greece and Rome studied the human body and developed conventions that were passed down by artists through the ages. Renaissance painters made great strides in learning how to paint fabric and metal surfaces. Hundreds of generations have explored different approaches to painting the human face.

But trains were different. Trains were still relatively new when Helck was born, so he could not rely on generations of artistic solutions. Artists were still shaping the basic traditions for painting the speed, power, smoke, and other features of a locomotive. Helck’s love and enthusiasm for trains made him well suited for inventing and popularizing their images.