Read all of art critic David Apatoff’s columns here.

This is the second in a series of columns about how to recognize the “art” in a Norman Rockwell painting. See Part 1 on Rockwell’s use of hands.

Whistler’s famous painting, Whistler’s Mother, is not really about Whistler’s mother.

The actual name of the painting is Arrangement in Grey and Black No. 1. As the title suggests, the purpose of the painting was to focus on the strategically placed dark and light elements in the picture. Art critic Kathryn Hughes wrote,

The subject is not Anna Whistler at all, nor is it Old Age, Wisdom or Regret or any of those other sententious one-worders that the High Victorians liked to affix to their drawing-room art. Rather, it is a commentary on… picture-making. Using a severely restricted palette, Whistler draws attention to the arrangement of large, simplified forms, so that the curves of the model’s face, dress and chair are grounded by the rectangles of the curtain, footstool and the floor.

Whistler believed in the modern art doctrine of “Art for art’s sake,” and was focused on the quality that artists call “value” — that is, the lightness or darkness of a color.

All great painters must learn to master the value of colors: the gradation of color from white to black, from light to dark. From the dawn of art, value has been one of the key organizing elements of painting. To control a painting and make the parts work well together, every artist must first decide which spot will be the lightest and which will be the darkest. Having established this, the painter can then relate all the middle values to these opposites.

As modern art became more abstract in the 19th and 20th centuries, “value” came out from behind the scenes and took center stage. Radical artists such as Whistler even made value the subject of a painting. His painting cares more about the dark and light shapes in his composition than the sweet old lady you think you’re seeing.

Norman Rockwell was never concerned with such abstract themes, right? He was really more interested in painting funny anecdotes for the cover of the Post, wasn’t he?

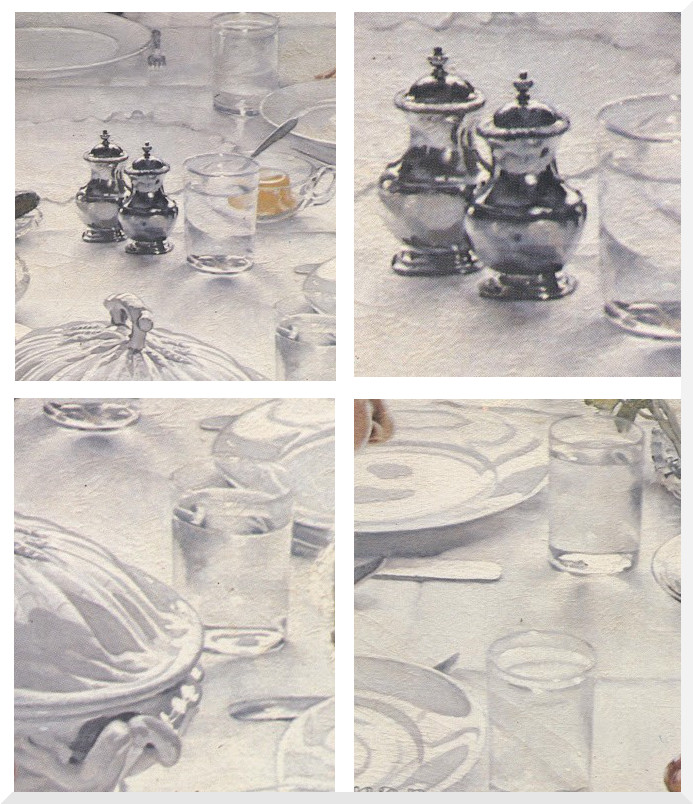

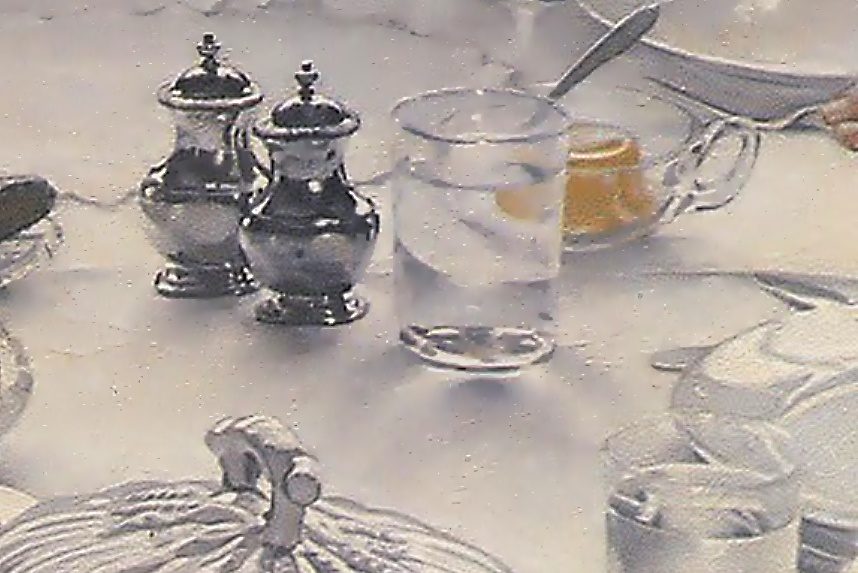

Well, it turns out that Rockwell was a master of value. Look at how he has stripped away almost all color in these paintings and focused on the subtle gradations of black and white:

These are virtuoso paintings in black and white, reinforcing that Rockwell was acutely sensitive to the range of “value” in his paintings, as much as the greatest fine art masters.

Why haven’t you seen Rockwell’s elegant black and white masterpieces before? Because they were hidden in plain sight, right smack dab in the middle of Rockwell’s famous painting of Thanksgiving that you’ve seen a dozen times:

It is true that Rockwell was also interested in “painting funny anecdotes for the cover of the Post,” and that misleads some people to think he was less of a fine artist. But if you look at the raw ingredients of art in his painting, Rockwell understood value just as well as Whistler. It’s just that Rockwell was able to focus on more than one goal at a time.

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

When are they going to give Norman Rockwell space on the walls of modern “art” museums? Trudging along a row of blurry, confusing canvasses at MOMA I finally saw something hanging beside the exit door that I understood and appreciated. It was a fire extinguisher.

When are they going to give Norman Rockwell space on the walls of modern “art” museums. Trudging along a row of blurry, confusing canvasses at MOMA I finally saw something hanging beside the exit door that I understood and appreciated. It was a fire extinguisher.