Read all of art critic David Apatoff’s columns here.

This is the third in a series of columns about how to recognize the “art” in a Norman Rockwell painting. See Part 1 on Rockwell’s use of hands and Part 2 on his use of black and white.

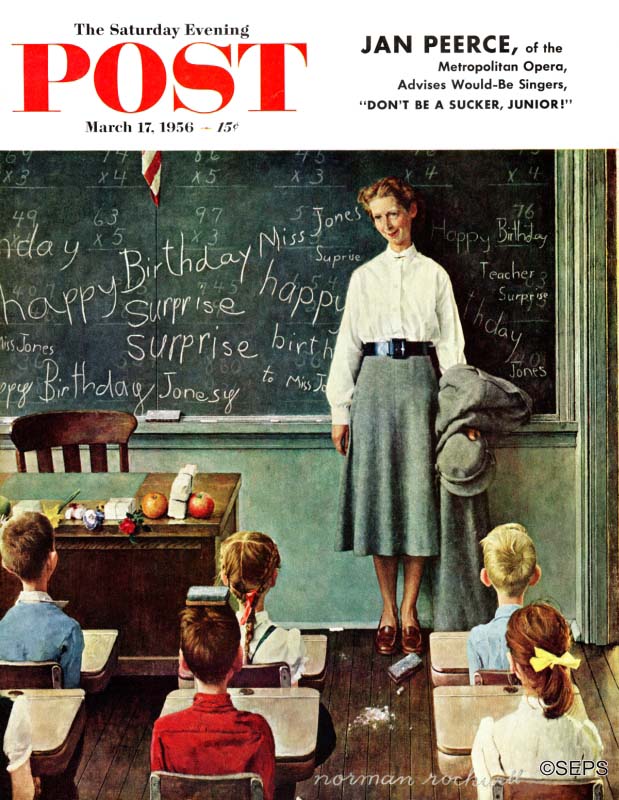

When you look at this charming painting of a teacher being surprised by her students, the first thing you notice is the teacher standing against the blackboard. You start with the expression on her face and then pull back, looking for clues about what’s happening. Next you read the words on the blackboard and learn that this is a birthday surprise. Then you gradually notice the rest of the details. The gifts on her desk, the personalities of the individual children, the chalk dust on the floor from the children scampering back to their seats before the teacher walks in.

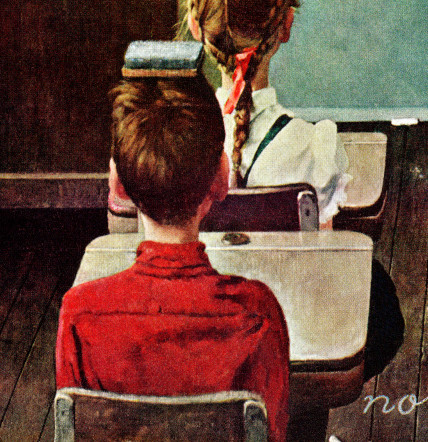

If you started looking at the picture from a different spot — for example, the class clown balancing the eraser on his head…

…or the chalk dust on the floor…

…this painting would make little sense at all. You’d wander around the page at random before eventually stumbling across its meaning.

How did you know to view everything in the proper sequence? The answer is because Norman Rockwell used a painter’s tools to lead you around the painting in exactly the order he wanted. He established all the priorities for you.

When we read a book, we follow a clear set of rules: for readers of English, we start at the top of the page and read from left to right, working our way to the bottom. Along the way, we follow the traffic signals provided by punctuation. But artists work with a very different set of rules to guide us in “reading” a painting. Certain visual elements demand priority attention. Our eyes are naturally attracted first to bright colors, or to high contrasts between extreme colors (for example, when an artist places black next to white). Certain shapes cause our eyes to move in a particular direction, or at a particular speed. Certain subjects, such as human faces, seem to grab our attention. On the other hand, some devices signal us to leave less important parts for later: subdued colors, soft boundaries, earth-colored tones and other devices don’t compete for our attention, so artists use them for backgrounds.

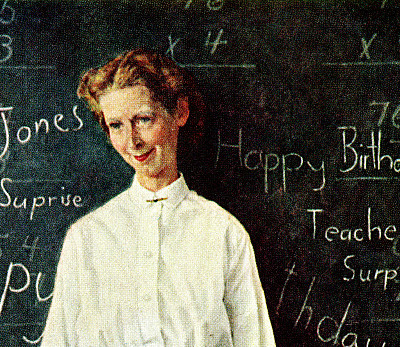

Returning to our painting of the teacher standing in front of the class, Rockwell starts us with the teacher by contrasting her stark white shirt against the blackboard.

Notice that a few of the girls in the classroom are also wearing white, but they don’t compete for our attention because their white dresses aren’t as noticeable. Why? Because they are contrasted against light brown and pale green colors, not black. Rockwell also gives the teacher visual priority by making her the largest object in the painting. It helps, too, that hers is the only face in the painting — we only see the backs of the heads of the students. We aren’t conscious that Rockwell is doing it, but he walks us through every step of that painting, telling us how long to linger and where to turn next.

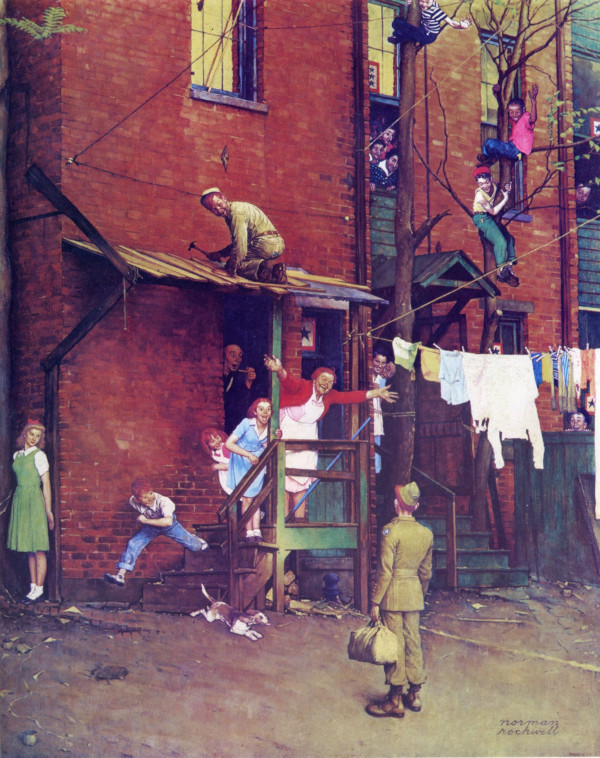

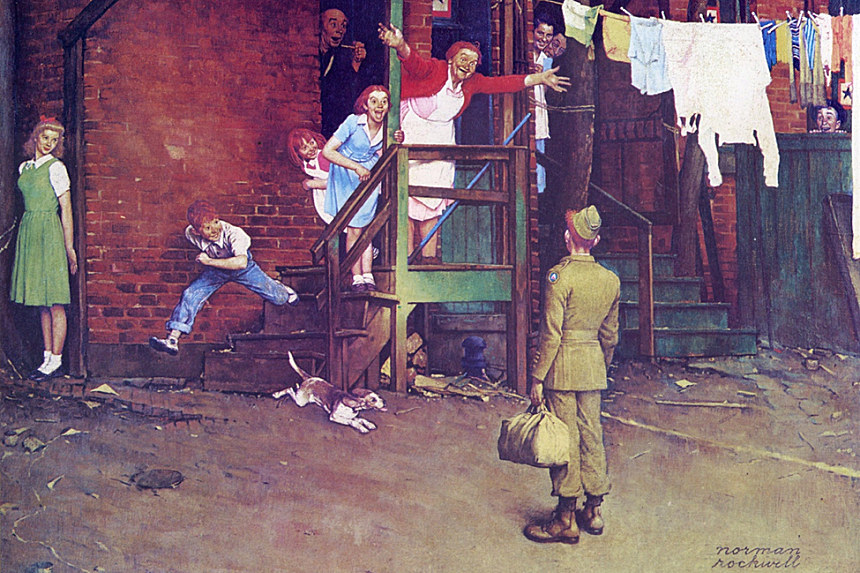

In this next painting of a soldier returning home from the war, Rockwell takes control in a very different way.

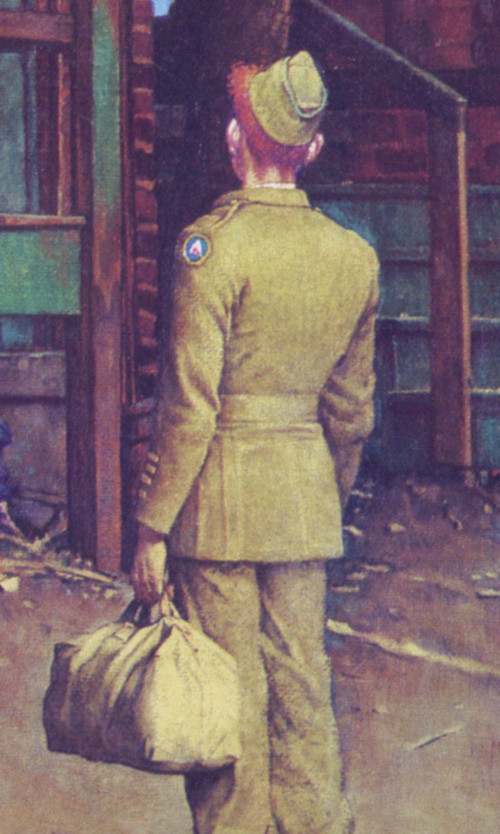

Unlike the school teacher, here the center of attention is a tiny part of the picture, with his face turned away from us:

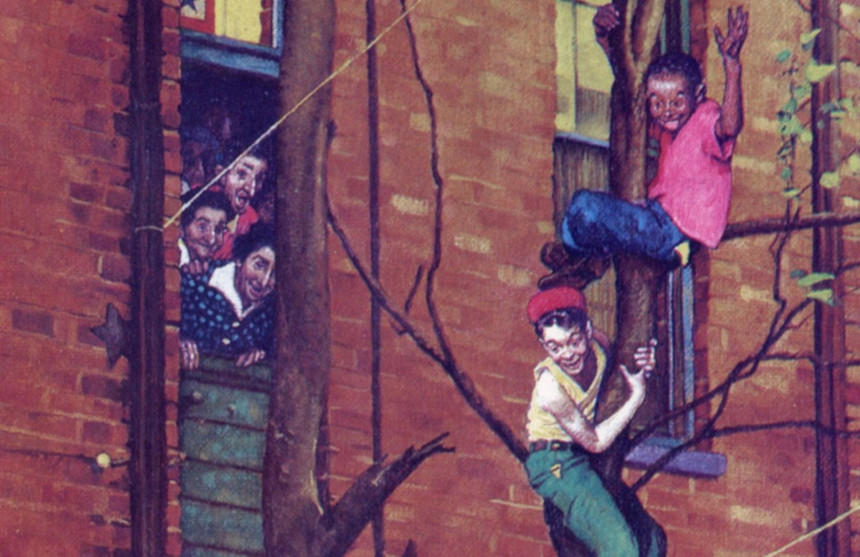

So how does Rockwell do it this time? How does he orchestrate a picture with eighteen figures in it? He achieves it by employing the eyes and faces of others. Seventeen characters in the painting are all focused on just one thing: the eighteenth character. We don’t see the soldier’s face, but he is surrounded almost 360 degrees by excited people looking directly at him:

No matter where you look in this painting, the faces of those characters lasso you and drag you back to where Rockwell wants you to look: at the homecoming soldier who makes everything else in the painting make sense. Small and inconspicuous, he is the glue that binds the whole painting together.

And there is a lot to bind. There may be as many as a dozen different stories going on here. If Rockwell were a writer, he would have to explain to us which of these characters are the soldier’s family, and which is his shy sweetheart waiting to see how her returning soldier feels. The deft Rockwell establishes that by giving the soldier’s family members distinctive red hair, a wonderful storytelling tool. A writer might spend a paragraph describing the soldier’s emotions, but by making the soldier so small, Rockwell the psychologist shows us how overwhelming the sights and sounds of home are. This is an excellent example of how visual story telling can be more profound and subtle than words. The picture would not be nearly as powerful if Rockwell hadn’t staged it to give us the view over the soldier’s shoulder.

Staging a painting is important because our eyes can’t absorb everything in a picture at once. Our eyes see things, and perceive meaning, in stages. Writers tell stories in orderly sentences and paragraphs that are designed to present a narrative in linear form. But great artists such as Rockwell can unfold a narrative just as well — sometimes better — using visual elements.

All images by Norman Rockwell, © SEPS

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

l’ve always been in awe of Norman Rockwell. Having lived in New England off and on for many years I’m fascinated by how he has gained even more popularity over time. He was definitely blessed with his understanding of his art form. Another unique thing about Norman Rockwell is his use of lower case letters in his name!

The best part of it, and the part which really took me, is “the sweetheart,” as the writer refers to her. But I don’t agree that she’s “the sweetheart.” Her posture makes it obvious that she yearns to be that, but she’s obviously very young, probably not eighteen, and the posture tells us that she’s had a crush on him for many years, but isn’t at all certain that he’ll reciprocate. To me, it’s by far the best, most subtle detail of this brilliant piece.

Thank you for part #1, 2 and 3.

Now I can look at his astonishing pictures with more awareness. Thank you so much.

Love the article! I am a HUGE fan of Norman Rockwell! Over the past 40 years I have collected so many items with his paintings, from miniature playing cards to joining a figurine membership club. Enough to fill three (3) cabinets. Have never been to the museum which is on my bucket list to visit one day. Saturday Evening Post, you’re the best. Thank you for so many years of enjoyment of Norman Rockwell.