It’s All Very Taxing: Why We Pay on April 15 and Other Tax Facts

Taxes remain one of the great contradictions of society. No one likes to pay them, but basic things like roads, police and fire departments, public schools, public parks, and thousands of other necessities wouldn’t exist without them. We spend a lot of time dreading the filing and paying of taxes, and seemingly more time waiting on any refund we might have gotten. However, we spend precious little time thinking about the basic facts of taxes. Why is Tax Day April 15? Does filing have to be complicated? How much of my taxes go to which programs? Today, we take a quick look at four of the more taxing questions.

1. Why is Tax Day on April 15?

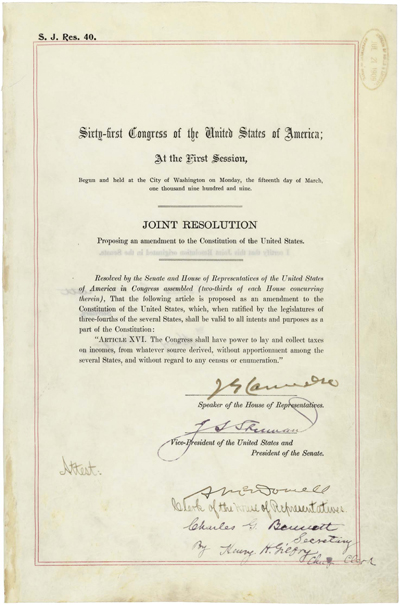

Tax Day has been fixed on or around April 15 since 1955. Income tax has been a constant since the Revenue Act of 1861, which went into effect to levy monies from income to help pay for the Union’s war expenses. If you made more than $800, you had to pay a three percent flat tax. That was repealed in 1871, but a new flat federal income tax law went into effect in 1894. The Supreme Court threw that one out, based on a claim that taxes needed to be tied into population distribution. The population question was eliminated by the 16th Amendment, which was passed in 1909 and ratified in 1913; the amendment allowed for an individual income tax regardless of population.

In 1913, the filing deadline was March 1. That was pushed to March 15 in 1918. During tax code reforms in the mid-1950s, the date got pushed again, this time to April 15. The basic reason is that, well, it takes a lot of time to do all the paperwork. Knowing that there’s a deadline down the road, it theoretically gives people all of January, February, March, and half of April to do their filing for the previous year. However, very few people do it as soon as the calendar turns (“As soon as I kick this New Year’s hangover, I’ll file my returns” is not a common sentiment).

2. When Did Electronic Filing Begin?

You might think of e-filing as a relatively recent innovation, but it’s actually been available since 1986. That’s right; 33 years ago, five tax preparers agreed to take part in the first e-file program. It waspretty complicated; the preparers used a Mitron, which was a machine that was basically a tape reader connected to a modem. The tape with the tax data would go into the Mitron; the data would then transfer via the modem to a different machine at the IRS called a Zilog. The Zilog read and reconfigured the data for the Unisys computer that the IRS had at the time. Like we said: complicated.

By 1987, the IRS began to allow electronic direct deposits so you could get your refund as soon as possible. The next year, they shed the complicated Zilog system in favor of IBM Series I. With the continuing evolution of electronic communications and the internet, half of all returns were e-filed by 2005. The IRS stopped mailing out 1040s in 2010, making them and other forms available online.

3. Isn’t This All Simpler in Other Countries?

In a word, yes. A number of countries have what we call “return-free” taxes. That is, the equivalent of the IRS does your taxes for you ahead of time, sends you a verification form to make sure everything is correct, gives you time to make sure it’s right, and then you send it back. That’s how it works in Spain, Denmark, and Sweden. Japan and the U.K. use “precision withholding,” which are regular withdrawals that take care of what you owe while accounting for your charitable contributions.

While some complications stem from the fact that our tax system tries to be fair and observe that differences in income can affect how people are taxed, that’s only part of the issue. In the U.S., efforts to make your filing easier, and even free, have been undermined by lobbying. Intuit, the makers of TurboTax, has spent $20 million in lobbying in the past 10 years to keep things the way they are. Confusing legislation exists right now that would ban the IRS from making their own free tax-filing software available, keeping private companies like Intuit and H&R Block in control. The legislation would require the companies to make free software available to everyone that makes under $66,000 a year, but that could be a problem for people who file jointly, depending on the specificity of the rules. It’s safe the say that filing won’t get much easier anytime soon.

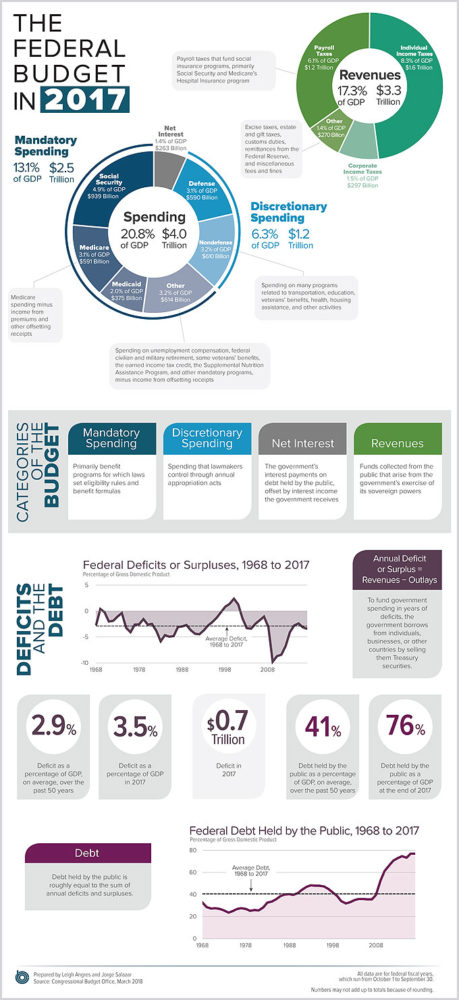

4. Where Exactly Does Our Tax Money Go?

This is a perennial question, but it got a lot more attention recently when rapper Cardi B asked about it on her Instagram in March. A number of outlets, like CNBC, rushed to provide answers and statistics. Citing the Peterson Foundation, the article indicated that about half of our discretionary spending (the spending that lawmakers control with appropriations) from tax revenue goes into defense, which was roughly $6.11 billion in 2017. For context, the Foundation notes thatU.S. defense spending is “more than China, Saudi Arabia, Russia, United Kingdom, India, France and Japan [defense spending] combined.” In other discretionary funds, six percent goes into education, with another six going into Medicare and related accounts. When we examine what is spent on “mandatory spending,” which are programs that have been set by laws, that goes to things like science, agriculture, transportation, social security, health care, and anti-poverty accounts like SNAP.

Like them or not, taxes, simply put, are how we pay for things in America. Different countries may have different priorities and programs, but they typically push toward the same rough equivalent, which is an overall attempt to provide services and security to citizens. Whether we pay in March or April, whether we file on paper or on a computer, taxes always come due.

Featured image: Shutterstock

50 Years Ago This Week: Abolishing Poverty

This Post editorial by Stewart Alsop from 50 years ago visits a theme that is still a concern today: pervasive poverty, and how to solve it. Alsop examines — and then quickly rejects — the idea of a guaranteed basic income. The debate continues today. Some economists support this extensive safety net, and others dismiss it.

There is a lot Alsop got wrong: he hoped the “Vietnamese War” would end quickly (it didn’t), that public assistance would soon wind up in the ash can (it hasn’t), and that Lyndon Johnson was a cautious politician (he wasn’t). Whether he was right on the dangers of a guaranteed income are still being debated, and are unlikely to be acted upon anytime soon.

After Vietnam — Abolish Poverty?

By Stewart Alsop

Originally published December 17, 1966

WASHINGTON: It may seem foolishly early to be thinking about the end of the war in Vietnam, and what will come after it. But all wars end someday, and already the Government’s leading thinkers are thinking hard and long about the role of Government in the postwar period. To judge from the way they talk, they are thinking more and more seriously about an idea which at first sounds both madly extravagant and faintly ludicrous. The idea is to abolish poverty once and for all by putting a floor under the income of all American citizens. “The way to eliminate poverty is to give the poor people enough money so that they won’t be poor anymore.” says one Government thinker. “If the war ended, we could do that very easily with the money we’re now spending in Vietnam.” The official Government standard for poverty — a four-person, nonfarm family with an income of $3,130 or less per year — now applies to about 17 percent of the total U.S. population. To give these poor people “enough money so that they won’t be poor anymore” would cost somewhere between $12 billion and $15 billion a year — well under the $2 billion a month that Vietnam is now costing. For about two percent of the Gross National Product, in other words, poverty could be abolished in the United States. All American citizens, as a matter of right, would be entitled to a minimum, non-poverty income. And this is where the proposal begins to sound faintly ludicrous. For “all American citizens” would include the drunks and the drug addicts, as well as bad people, immoral people and just plain lazy people. At first blush, it seems wildly unlikely that any administration will risk a proposal that would reward the undeserving poor as well as the deserving poor. No politician wants to be accused of taxing honest citizens in order to subsidize worthless citizens in the purchase of booze or reefers.

And yet the idea of a national minimum-income guarantee is a perfectly serious idea all the same, which is already being seriously debated by serious men. As always in the Johnson Administration, those in official position are reluctant to be quoted by name for fear of infuriating the President. But there are plenty of men still in the Government who agree with such recently departed officials as Joseph Kershaw, provost of Williams College, and Prof. James Tobin of Yale. Kershaw was until recently chief economist with Sargent Shriver’s Office of Economic Opportunity, and Professor Tobin was formerly a member of the Council of Economic Advisers.

Kershaw says confidently that the minimum income guarantee is “the next great social advance…. In the long run it’s inevitable, it’s got to come.” In a recent magazine article which has attracted much attention among Government economists, Tobin argues with conviction that “the upper four-fifths of the nation can surely afford the two percent of Gross National Product which would bring the lowest fifth across the poverty line.”

The basic idea for a minimum-income guarantee was first put forward by Prof. Milton Friedman, who is the chief economic idea-man for — of all people — Barry Goldwater. Friedman called for a “negative income tax,” to be administered by the Internal Revenue Service, to take the place of all federally subsidized relief for the poor. Friedman must have been surprised, and possibly appalled, when his idea was seized upon, and enthusiastically elaborated, by liberal economists like Tobin.

Tobin gives this illustration of how the scheme might work: “The Internal Revenue Service pays the ‘taxpayer’ $400 per member of his family if the family has no income. This allowance is reduced by 33% cents for every dollar the family earns. . . . At an income of $1,200 per person the allowance becomes zero. . . . At some higher income . . . the present tax schedule applies.”

Tobin, Sargent Shriver and others who have interested themselves in the idea point out that although the scheme would cost a lot of money it would save a lot of money too. Direct public assistance to the poor — federal, state and local — now amounts to about $5.5 billion, and the trend is sharply up. The minimum-income guarantee, in theory at least, would consign the present immensely complex system to the ash can. Virtually all economists, left, right and center, seem to agree that the ash can is where that system belongs.

It is a bad system for several reasons. First, there is the “man in the house” rule. The Aid for Dependent Children program is the biggest of the federally subsidized plans. Under the program, as administered in most areas, aid can be provided to a family only if there is no employable male in the household. The result, as Tobin points out, is that “too often a father can provide for his children only by leaving both them and their mother.” He calls this incentive to the disintegration of family life “a piece of collective insanity.”

Moreover, the “means test” tends totally to kill all initiative. The idea of the means test is that a family will get public assistance only to the extent that it cannot pay its own way. In practice, the result is that a poor man who earns $1,000 toward the support of his family doesn’t profit by a penny, since the $1,000 is subtracted from his relief checks. Under the “negative income tax” system, he would keep part of every dollar he earned.

The means tests and other complicated bureaucratic requirements of the present system tend to turn the social workers who administer the programs, willy-nilly, into part-time spies and policemen. In Negro ghettos, hatred for the administrators of the relief programs is almost universal.

There are, of course, plenty of objections to the whole idea of a universal floor under incomes, quite aside from the vast cost. A program with a price tag of $12 billion to $15 billion might crowd out the “structural” programs — preschool education, job training, slum clearance and the like — which are designed to help the poor escape from poverty. “You’d be treating the symptoms of the disease,” says one critic of the idea, “while letting the disease itself get worse and worse.”

Enthusiasts for a minimum-income guarantee counter that a good doctor treats the symptoms as well as the disease. But the deepest and most instinctive opposition to the idea derives from “the Puritan ethic.” By the standards of conventional morality, it is just plain wrong that a man — especially a bad man or lazy man — should be paid money which he had done nothing to earn by the sweat of his brow. This is why, even to many who like the idea, it seems highly unlikely that Lyndon Johnson will ever buy it.

Lyndon Johnson will certainly not buy the idea while the Vietnamese war continues. He is a cautious politician, and he may never buy it, even if the war ends. But Lyndon Johnson is also a man very conscious of his place in history, and the President who abolished poverty in the United States would certainly occupy a rather capacious niche in his country’s history.