Why Is Our Country So Divided (and What Can We Do About It)?

The name of our nation claims we are united, but one could compile a history of America just by chronicling our civil conflicts. Starting with the clash over the independence movement, Americans have been bitterly divided over tradition, faith, morals, and the rights of people of color, women, the poor, immigrants, and other groups. And, of course, we are divided between political parties.

Today, there’s a deep gulf in American opinion, which seems to be growing wider and deeper.Back in 1994, a Pew Research Poll reported that the partisan split over racial discrimination, immigration, and international relations was 15 percent. By 2017, it was 36 percent.

Spencer Critchley, author of Patriots of Two Nations: Why Trump Was Inevitable and What Happens Next, says that behind many of our arguments lie polarized views of the world that go back to our earliest days.

Critchley explains that on one side are the followers of Enlightenment, who believe in science, reason, and the rule of law. It was enlightenment thinkers who framed our government and wrote our Constitution. Today’s followers of the enlightenment believe in a “civic nation,” founded on a social contract between the individual and the state. The citizen exchanges a measure of personal liberty for membership in a mutually supportive society.

On the other side are followers of the Counter-Enlightenment, who believe a focus on reason is too constraining. It doesn’t account for culture, art, tradition, spirituality — the elements that bring richness to life. This group believes in an “ethnic nation,” which is rooted in their race and culture. While this focus can appeal to bigots, counter-enlightenment people are not necessarily racist. In an interview with the Post, he said,“Many thoughtful people come from the counter-enlightenment world view.”

The gap between the two world views is so great that Critchley, a former campaign advisor to Barack Obama, says that it has created alienation and suspicion, helped on by politicians and the media playing on resentments. “Much of the division has been exaggerated,” he says. “A lot of money can be made by making people angry and afraid.”

Yet there are a considerable number of Americans who have embraced the extremes of ideology. At the far extremes of counter-enlightenment are white supremacists. At the other extreme are people who Critchley says believe in “identity policing, endless litigating, political correctness, and punishing people for not being ‘woke’ enough.”

Critchley, who considers himself part of the enlightenment crowd, is aware of how easy it is to dismiss the opposing points of view. He says, “We live lives of high rationalism most of the time. We think in terms of facts, logic, productivity. We tend to believe facts and logic explain everything.”

The two groups’ attitudes toward culture is significant, he adds. “Enlightenment people can become disconnected from any particular culture. This is part of what’s behind the ‘globalist’ charge. Sometimes that refers to the global financial elite, and sometimes it’s veiled antisemitism, but it can also point to this sense of cultural emptiness.” Critchley says that globalism is a concept that disconnects people from the symbols and traditions that shape their lives. Critchley compares it to the campaign to teach Esperanto, “the international language.” He wonders at “the idea that anyone would want to speak a language rooted in no culture at all.”

What is true in language is also true of history, art, and human psychology. Counter-Enlightenment people “would argue that people are inherently subjective and tied to a particular location.” Culture is crucial.

Says Critchley, “The Democratic party — I’ve seen it up close — is sometimes stuck in a science-driven world. They’re really good at using science and coming up with solutions.” But they can be oblivious to culture.

“A lot of liberals would be surprised that while more than 90 percent of Blacks consider themselves Democrats, only about a quarter would define themselves as liberal.” Critchley says that they need to recognize “there are many cultures alive in the Black community.”

The current level of social friction threatens to get out of hand. But the situation can’t be blamed on a polarizing president and the general tone of today’s politics, Critchley maintains. The ideological division is far older and runs far deeper, and will still be with us after this administration has gone.

Sooner or later, we must make the effort to reunite. The solution, Critchley says, is like dieting: “it’s simple but it’s hard.”

When talking with someone with a different perspective, he advises, “stop trying to make sense for a while, stop trying to correct them. Practice some awareness, compassion. And find some shared values.”

It will probably take some digging and the results may be surprising. “We must learn to respond to people in a more intuitive way,” Critchley says. “We must build trust. Connect first, debate later.”

Featured image: Map from the cover of Patriots of Two Nations: Why Trump Was Inevitable and What Happens Next by Spencer Critchley (McDavid Media, ©Spencer Critchley. All rights reserved.)

An Interview with James Brolin

James Brolin has won generations of fans since he first became a hit co-starring in Marcus Welby, M.D. His sense of humor and down-to-earth perspective on show business is front and center when he remembers with a laugh, “They gave me an Emmy and a Golden Globe for that role. There were tears just running down my cheeks in a scene where I was reading an emotional letter. I should have thanked salt water and menthol for helping me cry.”

Brolin’s imposing 6-foot-4-inch stature and craggy profile helped make him a star in a string of TV series and movies, from Hotel to Westworld, from Amityville Horror to Traffic. He reveals his biggest challenges were playing two real-life legends, Clark Gable in Gable and Lombard and Ronald Reagan in The Reagans.

He was delighted to score again in a juicy supporting role in four seasons of the popular CBS series Life in Pieces as Pop-Pop. “I loved that it was so real in dealing with family relationships,” Brolin says. “I didn’t know how much fun I’d have with a great cast.”

Next up for the 79-year-old is Sweet Tooth, Robert Downey Jr.’s new series based on the DC comic. Lots of young comic fans have already shared their enthusiasm for Brolin as the narrator. And at the top of his wish list is directing a movie based on the true story of Ruby McCollum, a wealthy African American who was convicted of killing a prominent Florida state senator in 1952.

Brolin is proud of the wide collection of characters he’s played, but he still jokes, “I’m Barbra Streisand’s husband and Josh Brolin’s father. Those are my important credits!”

Jeanne Wolf: Do you still have the same enthusiasm for acting after such a long, distinguished career?

James Brolin: My kids figured out that I’ve spent about 9,500 days on film and TV sets. I’ve been in heaven every one of those days. Every minute you put in makes you better than when you started. For me, the tough part was often what it takes to get ready. I was a shy guy when I was young, and that would come back in mental blocks. When I felt truly up the creek, I’d drive from L.A. to Bakersfield with a script and keep reading it aloud along the way. It’s a four-hour trip and I would go into a sort of alpha state, but by the time I got back, I knew every line.

Then there were times when I had doubts and fears about playing larger-than-life characters, like Clark Gable in Gable and Lombard and Ronald Reagan in The Reagans, even though the directors really wanted me. I had to be convinced. After a lot of hard work, I saw that they were right.

I kept saying I wasn’t right to play Gable in Gable and Lombard. And Sidney Furie, the director, kept saying, “You can do this. I’m putting you in the screening room and you’re watching Gable movies for two weeks. And so I did, and that changed everything in my mind. Sidney was right.

When I did the president, I’d be walking around my hotel room at three in the morning holding my computer watching clips of him and thinking, “I’m not this man. How do I become him?”

I also had my doubts about taking a supporting role in Life in Pieces, and it ended up being four rewarding years. I think I put a little of my own dad into that character, which is funny because when I said I wanted to be an actor, he went, “I’ve got a 10,000-to-1 bet against you.” Then, after I became successful and changed my last name from Brudelin, he made reservations using Brolin. Suddenly, he was Henry Brolin.

Actually, playing all those roles hasn’t been just for me. I’m trying to get butts into theater seats to really have fun for a couple of hours. You’ve got to keep the audience in mind whether you’re acting or directing. You can’t leave them bored. I feel that we’ve seen so many movies and TV shows go by that wowing people is tougher than ever. A film ends up like day-old bread from the bakery, worth half the price. You kind of have to go, “Okay, what’s next? What can I do better than I did before?” At my age, I have to swallow this pill of, “Will I ever work again and will it be worthwhile?” But I love being on the set. Making a movie brings together people who are the best enablers, so full of ideas and wanting to please. When I was directing, I’d give them a challenge and wonder how they pulled it off. They’d say, “I just gave you 30 percent more than you paid me for.” They don’t know any other way.

JW: You have many talents and things you love. Is that your personal secret to youth?

JB: As a teenager, up until I was 18, I would go to the UCLA library and wander through different sections. I didn’t love school, but I loved to explore things. I’d think, “Oh, photography, that sounds interesting.” I’d find a book and start reading it. And then I would just get bored, and go, “Okay, enough of that.” And I’d go to another section. Sometimes, I would be there all day and maybe delve into five different subjects. I could learn more in the library than sitting in classes.

I feel like I’m in a hurry now because there’s so much to learn. And there’s travel, not that we’re going anywhere during the pandemic, but there’s so much yet to see. You go to Google and type a city, like Tonga, in middle of the Pacific. And you go, “Man I want to go there,” but there’s no time.

It’s funny. A lot of people sat around at home during the pandemic wondering what to do. I feel like I don’t have time to do everything, and going to work would be a vacation. Right now, I’m studying to get my commercial pilot’s license. My dad was an engineer who worked on the Douglas DC-3, but he was never a pilot himself. I took my first flight at 18 and was hooked. I’ve been flying for 50 years.

And I’ve always loved cars. I just got a new Porsche, but basically I drive a Mini Cooper and, of course, my Raptor truck with the big tires. That’s the cowboy side of me.

And I’ve just bought a lot overlooking Malibu Lake that tilts at a 45-degree angle. They say you can’t build on it, but I’m going to put up a sweet little house there. And I’m doing workouts with the big wave surfer, Laird Hamilton. He puts me underwater in my pool with a 20-pound weight in each hand, and I have to get to the surface before I run out of air. I’m in the best shape ever. So life is good, and you’re invited to my 100th birthday, whenever that it is.

JW: You’ve been married to Barbra Streisand for over 20 years. What’s your secret?

JB: We really do have a wonderful time. We certainly are very different from each other, but being at home so long during the quarantine was proof of how happy we are to be together. I’ll tell you, things are never dull, and after we each do our thing all day, we are just glad to see each other. That doesn’t mean we don’t pick at each other like people do, but we have an instant laugh about it. Or you go off in the corner, and when you come back, pretend like nothing was ever wrong in the first place.

After practicing in two other marriages, I got it down pretty good. Barbra corrects me and I push her, but she backs me up in all of my passions, from flying to directing. I appreciate the extraordinary things she’s done, but people would be surprised at how simple the things we love are. When you decide that this is a lifetime deal, you think of ways to make each other’s life better. You don’t expect everything to be perfect, but it’s perfect because you trust each other and you are there.

JW: What’s in the future for you and your family?

JB: Barbra really believes in leaving a legacy, so she’s been tied up writing a book about her life and career. There have been a lot of false stories about her, and she’s setting the record straight. She’s a truthmonger.

But I’m easy, and my mother was easy. When I decided I wanted to become an actor, Mom said, “Whatever you want to do, just go for it. I’m with you.” You’ve got to roll with the punches a little bit. Give people a little room. If you get a dog from the pound and he bites you, give him a little food and a little love, and don’t forget that someday he might still bite you again.

I don’t know how I’ll be remembered. Maybe as Josh Brolin’s dad. I watched him through all his ups and downs. As a father I was there to catch him if he fell. In the meantime, I couldn’t advise him. If I insisted on anything as Josh was growing up, he would either disappear or just be totally angry. It didn’t work like it does in a movie. During the pandemic, he’s been Mister Dad, staying at home and changing diapers, but he’ll soon be busy again. We’re all just proud and waving at him as he passes by.

This is the full version of an interview that ran in the September/October 2020 issue of The Saturday Evening Post. Subscribe to the magazine for more art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

Featured image: Photo by Gilles Toucas

The Heartland and the Myth of the “Real” America

In 1958, The Saturday Evening Post published a series called “The Changing Midwest” that attempted to document the transforming towns and cities of the “once-isolated midlands” of the U.S. In an interview with a banker from Rushville, Indiana, the Midwesterner puts it plainly: “The old days are gone.”

It’s a sentiment that has been expressed in various ways for decades, but at its heart lies a question: What exactly were the “old days”?

In her recent book The Heartland: An American History, Kristin L. Hoganson uncovers histories of the so-called “flyover states” that challenge prevailing conceptions that the center of the country could ever be reduced to a homogenous, provincial set of Americans. As a historian with a background in U.S. foreign relations history, Hoganson contends that “America’s heartland” is as misunderstood as it is steeped in complicated, multicultural history with global reach. Rather than hailing as the “once-isolated” lands of American mythology, Hoganson says the Midwest has played an important role in the story of globalization, and our failure to understand its checkered — sometimes unsettling — past is a detriment to our country’s future.

In our interview, Hoganson discusses her book, what we might be forgetting about the “old days,” and how American misunderstandings of the Midwest have brought us to our current political landscape.

The Saturday Evening Post: In your book, you focus a lot on this myth of the “heartland.” You write, “the more entrenched the myth became, the more natural it seemed. The more distant its origins, the easier it became to forget that it did not arise from solid historical and geographical analysis, but rather from the stuff of political need.” What is the myth of the heartland, and what “political need” did it arise from?

Kristin L. Hoganson: By the heartland myth, I mean the sense of the rural Midwest as a quintessentially all-American place: as local, insulated, and isolated; as the ultimate national safe space. This seems to make sense because of geography. The Midwest seems buffered from the rest of the world because of its position in the middle of the country. But the Midwest, like the rest of the United States, has never been walled in or off. There has never been a fixed essence that we can regard as a national heart. The political need that you mentioned is the nationalist desire for some kind of core, for a sense of who the American people are at heart. But of course, the heartland of myth doesn’t represent the nation as a whole. It overemphasizes the whiteness and insularity of the United States. The seemingly nationalist need that the heartland myth fulfills might better be understood as a white nationalist desire to separate insiders from outsiders; to make exclusionary claims about who and what count as fundamentally American. The heartland myth does a great injustice not only to the United States but also to the people it purports to depict, because it distorts their history and hides far more fascinating stories.

The origins of the term “heartland” are early 20th century. A British geographer, Sir Halford Mackinder, coined the word to refer to a locus of power. In opposition to naval theories that focused on the control of sea lanes as the key to geostrategy, he theorized that whoever controlled the Eurasian heartland would control the world. The term entered wide circulation in the United States during World War II in coverage of the fight for Europe. After 1945, the term continued to be used in reference to Eurasia, though with a focus on the Soviet threat. As the Cold War got colder, Americans began to apply the term to their own geographic center and capacity to wield power, as seen in references to the industrial heartland. Yet as the rise of long-range bombers and eventually intercontinental ballistic missiles fostered more anxieties about nuclear destruction, the term took on new meanings. In contrast to the hard-edged industrial heartland, which signified power, the soft-focus heartland came to signify Americana. This latter heartland became the heartland of myth: a repository for nostalgic yearnings, a place of innocence and national essence that had to be protected from outside threats at all cost.

SEP: How do you think that myth of the heartland aids politics today? Not necessarily Trump, but maybe any political program or politician that purports to understand the interests of Midwesterners.

Hoganson: The heartland myth lends itself to an exclusionary vein of nationalism by suggesting that there is a real America that is somehow threatened by the actual majority of the American people. The idea of the heartland as a buffered place also lends itself to the idea that the United States can achieve security by walling itself off from the rest of the world. And the idea of the heartland as a vulnerable place hides the role of the United States in forging the modern world and the tremendous global power it has exercised. My point is that there is no going back to the heartland of myth because it never existed in the first place. And to those who are attached to the myth, I’d say that the history I uncovered is actually far more interesting and epic.

In a time of talk about building walls, hypernationalism, that understanding of place is very relevant to those kinds of discussions. In terms of rhetoric, I think what my book argues against is a sense of victimization. I would refer specifically to Trump’s rallies, including in Ohio. I think, rhetorically, what is happening in some of those speeches is an effort to say, “The rest of the world has taken advantage of you.” That “we are victims of the rest of the world and we’re finally going to stand up to the rest of the world.” A major point of the book is to think of the impact of the rest of the world on places that may not have been considered to be points of encounter, such as the rural Midwest, but also to recognize that the rural Midwest has been a place of power. That it’s not just a story of victimization; it’s a story of colonialism and empire. The exercise of power, including in small, Midwestern towns, and the ways those residents have benefitted from global systems of power, and how they have been very active in advancing U.S. power.

In the book, one of the people I trace is William McKinley. Not President William McKinley, although he too comes from Canton, Ohio, small-town Midwest, and was the archimperialist of the turn of the 20th century. But the McKinley I trace was a congressman who made several around-the-world trips to the U.S. colonial outposts in the Philippines, he took Caribbean cruises where he visited the U.S. colonies in Puerto Rico and the base in Cuba, the Panama canal. He was an arch proponent of U.S. empire-building as well as an arch proponent of global governance at a time when the United States was the rising power on the world stage. It’s important for people to recognize the ways the United States has exercised power globally and to understand that contemporary feelings of victimization really distort the overall history of the Midwest in the world. Part of it is an urban story, but it’s also in less likely places, like the rural places I write about.

SEP: You write about reckoning with the past, and Americans and Midwesterners reckoning with their own past as something that hasn’t really happened. What do you think that would look like? Have we begun to in any way?

Hoganson: I think that’s what people are doing right now. That’s a lot of what this spring-summer 2020 moment in history is all about: asking hard questions about the nation. Why have we fallen so short of our principles and capacities and how can we achieve justice, equality, and inclusion? My book is part of this larger effort. It pushes us to go beyond misleading mythologies, however comforting they may be to some, to understand more boggling, disconcerting, and even deeply troubling aspects of U.S. history. We will never get to a better place without understanding where we’ve been all along.

I think the book does two things. It helps explain part of the country to the flyers-over who have, at least in recent years, looked down on the rural Midwest, in an effort to make that flattened sense of place more 3-D for those who have dismissed the rural communities at the center of the country. But I also wrote it for people who live in those communities who I think in many cases have not fully appreciated their own community histories. In part, I think that’s because in historical scholarship other parts of the country have gotten a lot more attention than the Midwest. It’s been considered by historians recently as an overlooked part of the country. We’re in the middle of a time of revival of interest in Midwestern studies and Midwestern history. So, I think for people who call this part of the country home, there has been a certain disconnect from their past because of the comparative dearth of scholarship. And the scholarship that has existed on the rural and small-town Midwest has tended to be inward-looking and focused on smaller-scale stories of daily life without as much attention to bigger narratives and issues of power.

SEP: How did researching the Midwest differ from some of the other topics you’ve written about?

Hoganson: I uncovered so many unexpected threads while I was researching the book that I could not possibly follow them all. It was really hard to let some of them go. I also wanted to signal that the stories I tell in my book are not the whole story – I unearthed countless intriguing leads that I could not pursue. So the “archival traces” that start each chapter are a way of pointing to paths not taken and leads not followed. They are also about the excitement of conducting historical research – of uncovering nuggets that raise more questions than they answer; that make you want to know more; that remind you how strange and unexpected the past can be and what an emotional wallop it can pack.

As for what made the research different than my previous books, I am a newcomer to agricultural history, so it was a revelation to learn about things like the application of phrenological principles to pigs and the racialization of cows and bees. Learning about economic ornithology – relying on birds for insect pest control prior to the development of synthetic pesticides – was also an eye-opener for me. So was the discovery that students from China, India, and the Philippines who had traveled to the United States to study agriculture made Midwestern land grant colleges hotbeds of anticolonial activism prior to World War I.

As all this suggests, I was staggered to discover how much evidence of global interconnection could be found in agricultural journals and reports. I also benefited tremendously from advances in digitization. The Illinois Digital Newspaper Collections – which are free to search, browse and download – contain millions of pages of searchable text that enabled me to track topics such as the UFO sightings that accompanied the rise of long-distance balloon competitions and support for global governance through the Inter-Parliamentary Union.

SEP: You wrote: “Since the beginning, the seeming locality of the Midwest has served colonialist politics, having originated in colonial denial.” Can you explain what colonialist politics you’re referring to? And what that colonial denial might be?

Hoganson: Locality did not exist in the Midwest until the pioneers – who had by definition come from someplace else – invented it. They did so in large part through the local histories they wrote, which established their place claims vis-à-vis the Native people they forcibly displaced. The idea of the rural Midwest as one of the last local places has hidden enmeshments in colonialism and empire. The history of the Kickapoo diaspora figures largely in the book as one example, but there are plenty of other examples, including histories of bioprospecting, military aviation in the barnstorming era, and piggybacking on the British Empire.

SEP: You moved to Champaign, Illinois from Boston to teach at University of Illinois. What was that experience like for you on a personal level?

Hoganson: I’m a sixth-generation Midwesterner, with family ties that go way back in Wisconsin, Ohio, Indiana, and Michigan. But I grew up in exile, mostly on the East coast. Even though I used to visit relatives in the Midwest as a kid and my first full-time job was in Chicago, I have to confess that I bought into stereotypes about flyover country. You can imagine my surprise when I turned on the radio upon moving to Champaign and got the weather forecasts for China, Argentina, and Brazil. I realized I had no idea where I’d landed. The book came from the disjuncture between my expectations and what I discovered upon arrival. I realized that all the books I’d been reading on globalization assumed that there were particular places of connection, and the corn belt was not one of them. Moving to Champaign made assumptions about urban globality and rural provincialism visible to me in ways that they hadn’t been when I was teaching in Boston.

SEP: The first chapter is about the Kickapoo people, who were removed from Illinois in the nineteenth century. So, how was the experience of researching the history of a largely erased group of people?

Hoganson: As a relative newcomer to Native American history, I was astounded to learn about the vast geographies traversed by the Kickapoo people in the nineteenth century. These stretched from the present-day Detroit-Windsor area, a historic homeland of the Kickapoo Nation, to the straits of Mackinaw, present-day Indiana, Illinois, Wisconsin, Iowa, Missouri, upstate New York, Washington D.C., Florida, Texas, Arizona, Kansas, and Oklahoma. People with Kickapoo names were performing on the streets of London in the 1850s as part of a traveling show.

Some Kickapoos moved to Coahuila, Mexico in the nineteenth century for respite from the pervasive anti-Indian violence they encountered in the United States, for a place of their own, and for the ability to move freely across space. One of the accounts that most moved me in the course of my research is that of Kickapoo people who lived under the international bridge between Eagle Pass, Texas and Piedras Negras Mexico, literally on the U.S.-Mexican border, before their U.S. citizenship rights were acknowledged in the 1980s. Their experiences may seem out of place in an account of the U.S. heartland, but Kickapoos have been heartlanders since before that term existed. Their claims to place precede the borders that have walled Indigenous people in and out.

Featured image: Farmer Raymond Coin at his 240-acre farm near Bemidji, Minnesota (Photo by Bill Shrout, March 18, 1961, issue of The Saturday Evening Post, ©SEPS)

3 Questions for Michael Caine

For The Saturday Evening Post, I’ve talked to the biggest and the best — the world’s most interesting, influential, and talented famous faces. I’m always asked about favorites. Right at the top of that list is Michael Caine. The best storyteller: He can mesmerize a table of A-listers like nobody else. A spectacular actor: Caine brings charisma and truth to a character with a mastery that only a few screen stars possess. Fans across generations adore him, yet this legend has a relationship with fame that is straightforward and down to earth. In his books and in person, he shares a sly wisdom that always leaves me laughing and thinking.

At 87, he’s still ready to step in front of the camera to play parts he can’t resist. You’ll see him in the upcoming Tenet, an action epic with a twist of time traveling from Christopher Nolan, who considers Michael a good luck charm as well as acting genius, and Best Sellers, a bittersweet comedy about an cranky, aging author. I’ve often asked Michael, with all that’s come his way, how much does he credit hard work and how much does he bow to good fortune? He says, “I gave God a hand.”

Jeanne Wolf: You seem to slip so effortlessly into every character you play but I know how very serious you are about your work. Does the intense dedication pay off as you hide the effort?

Michael Caine: If you’re watching me in a movie and you say to your companion, “Isn’t Michael Caine a wonderful actor,” then I’ve failed. You shouldn’t be noticing the acting. You should be wondering what’s gonna happen to the guy I’m playing. The art is to make yourself disappear.

There are actors who hold up a mirror and say, “Look at me.” I hold up a mirror and say, “Look at you!” My acting should be so human that you say, ”How did he know that about me?” What you should get from my performance, to quote Edmond Wilson, is a “shock of recognition.” I want people to see me on the screen me and say, “I am him.” They know if they met me in the street, I’d talk to them. I wouldn’t be in a limousine flashing by with two blondes and a bottle of champagne. Although, mind you, that’s not a bad idea.

When actors are nervous, it can screw up a scene because it will make the audience feel uncomfortable. I’m often kidding and joking right up to the minute when they call “action.” With me you feel comfortable because I make it look like it’s a walk in the park. But that can be a double-edged sword. It’s like watching Fred Astaire dance. People may think, It’s a breeze. I could do that. Believe me, it isn’t as easy as it looks. It’s like a sort of drug in a way. It’s getting it absolutely right and knowing you’ve done it and you couldn’t do it any better. Sometimes I say to the director, “If you want it any better, you’re gonna have to get someone else cause I can’t do it better than this.” And if you get to that stage, you know, it’s great.

JW: You’ve written a book about acting, yet you’ve said that watching films and doing films was your own best teacher. So what do you tell your young co-stars about what you’ve learned?

MC: I always used to ask old successful actors for advice. Every single one of them said, “Give up acting.” So I say to young actors, “Don’t ask me for advice. The worst thing is it’s free. If you had to pay for it, it might be worth something.”

Early on I took everything because I had no money and I came from a very poor family. Once I started making movies, I thought no one was going to offer me another one so I always took the next one. Finally, I realized I could stop that. From then on, the mistakes I made in choosing roles were genuine mistakes. I thought it would be a good movie and it wasn’t. That was that. But then you get to another period where you don’t have to work. I only do things that I absolutely cannot refuse. I could not refuse Phillip Noyce offering me The Quiet American. I couldn’t refuse being Austin Powers’s father, or Sandy Bullock’s beauty mentor, and, of course, the butler in Batman. One thing now is I don’t get the girl, I get the part. When I used to get the girl, she’d be the most beautiful. Now I get the most beautiful part.

JW: You have a wonderful marriage. You and Shakira Baksh have great joy together. Has experience taught you how to savor your rich personal life?

MC: I live life to the fullest every day. I believe in that. That’s my basic philosophy. Because this is not a rehearsal. This is the show. We’re not opening next Thursday; this is it, we open today. However old you are I think you have to make the most of your life. And I do. There isn’t a day passed where I don’t try to do something. They nearly retired me once, but I came back.

I have this photograph on my sideboard in my dining room. There are three achievements. There’s one of my holding an Oscar. There’s one of the Queen knighting me with the sword actually touching my shoulder. The other is me standing at the top of Sydney Bridge in Australia after an arduous climb.

I wasn’t a success until very late in life. I never made my first big proper movie until I was 29. I was already set in a very concrete way into the person I was going to be, so nothing ever fazed me. Maybe it started with my mother. My father, who was my role model, went away to the war in 1939. I was six. My mother didn’t say, “Oh, now I have to look after you on my own.” She said, “Now Michael, you have to look after me.” So she made a small man of me. I became my father, which stayed with me for the rest of my life. Looking back, I always figure that I’ve been very, very lucky, and I’m just in awe of how lucky I have been — not what I’ve done. That’s why I don’t gamble. I haven’t got any luck left.

This is the full version of an interview that ran in the July/August 2020 issue of The Saturday Evening Post. Subscribe to the magazine for more art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

Featured image: Denis Makarenko / Shutterstock.com

When Someone You Love Is Behind Bars

For many Americans, the crisis of mass incarceration is a daily encumbrance. These are the children, wives, boyfriends, grandmothers, nephews, and friends of the 2.3 million people who are locked up in the United States. Journalist Sylvia A. Harvey has spent time with family members of incarcerated people — having been a family member of one herself — and her recent book, The Shadow System: Mass Incarceration and the American Family, tells their stories in intimate detail.

Although many in this country still look at full prisons and see criminals rightly serving their sentence, Harvey maintains, as many others have, that the price we pay for so much incarceration can be tracked through generations of wrecked communities. She writes:

When people are incarcerated, we as a society rarely consider the lives — and the people — left behind. But their former lives don’t simply vanish. For their children, those prisoners remain parents. The collateral effects of mass incarceration cut through the immediate fabric first, then penetrate the entire extended family for generations. The most fragile of those impacted are the children.

If you’ve never met someone affected by America’s prison system, Harvey believes you should read her book. In our interview, she paints a picture of what life can look like when someone you love is behind bars. The costs, financially and emotionally, of the highest incarceration rate in the world are paid heavily by the families of the disproportionately black and poor prison population. Harvey says that this isn’t inevitable, and that the patchwork of policies and programs around the country often point to what works better, if only we can find the political will to act on it.

The Saturday Evening Post: In your book, you write about how you’ve been affected personally by incarceration. Can you talk about that?

Sylvia A. Harvey: Yeah, I experienced parental incarceration from my father for about 27 years in different California prisons. What’s been important for me, having that experience, is being able to utilize that to see what’s happening around the country to 2.3 million families, people who are directly impacted now. My father spent 27 years in prison, and that’s been significantly helpful in thinking about how policies need to change and how families are being impacted.

SEP: How did you find the families whose stories you featured in this book?

Harvey: That was actually a task. What I started to do was to call organizations from each state that was of interest for some reason. So, I picked Mississippi because of what’s happening there in terms of race relations. It is not a progressive state, so to speak. So, to look at incarceration and its impact on families in a conservative state, in a place like that, it meant calling any organizations that worked with families impacted by that. There weren’t very many programs, so it was difficult. So then I called local churches, local organizations. It was literally looking at what kinds of organizations were in place at the grassroots level.

Florida was a little bit easier because they had more organizations that worked with this demographic. I started to go along on some of the visits they had in Florida with the Children of Inmates program, going along on some of those trips and sitting in the visiting room. From doing some of that preliminary reporting, I was able to determine which families were most suitable for the book.

SEP: Could you give a rundown of the three families you covered in The Shadow System?

Harvey: In Miami, I looked at a young man, a young black man, who has a murder conviction. So, what does that mean for a young person in Miami to have this kind of conviction, and what does that mean for his daughter? In Jackson, Mississippi, now we have a family where the father has been incarcerated for 39 years. So, what does it look like to have a life sentence and to have served almost 40 years of that sentence? Being able to look back on how that manifests in his family, his three children who are all black boys. In Louisville, Kentucky, I was focusing on returning citizens, and predominately white women who were impacted by the opioid epidemic, as they returned home. So, looking at issues across the country with different demographics.

SEP: What surprised you about how other people who have been affected by incarceration live and cope with that?

Harvey: I think, the availability of resources. So, in different states you have different resources. That was — I wouldn’t say shocking — but why I decided to write the book in this way, to focus on states that are not represented often, the states we don’t really think about. It was surprising for me to see exactly how incarceration manifests. Like, how you could serve as much time as the man in Mississippi did and be able to look at other states where they’re releasing people.

I was surprised by the difference in legislation, the difference in sentencing, and the difference in resources. In Jackson, there weren’t very many resources, but if you go to Miami, there’s this program where they’re literally taking these children and their families all over the state to visit their parents in prison four times a year. This is a resource that is state-funded, so why doesn’t that exist in other parts of the country? There’s a disparity in resources available, disparity in sentencing, disparity in visitation, depending on where you are in the country.

SEP: How did visitation differ from case to case, and what does that process look like?

Harvey: In the book, my focus is on family visitation. So, family visitation was something that was taking place in Jackson, Mississippi. Family visits in that state were three to five nights, where you could literally go on prison grounds in a small apartment or trailer that’s sort of set up to mimic the idea of being home. That’s the kind of visitation I focused on because it’s obviously the most progressive visitation, and I wanted people to be able to look at that and see what that means. It means these families are able to go and feel like they’re at home again. The mother who has three children and a husband who’s been incarcerated for 39 years is able to continue to build with her partner by having these visits. That’s pretty significant. I think it’s important to be able to look at that and see what that means, what that feels like, and why it no longer exists in some states but still exists in others.

SEP: What does visitation look like in other places where they don’t have those types of programs?

Harvey: It really depends, so in some states you’ll have visitation that is behind the plexiglass, no contact, and in some places you’ll have video visits. A lot of jails are turning to video visits only, which means you’re going to the jail facility but only using video. Some visits allow contact, but it’s limited contact, so you go to the jail or prison and, for the first, maybe 15 seconds, you’re able to greet the person, give them a hug or kiss or whatever, but there’s a limitation on the physical contact you can have. Some facilities will allow you to maybe hold hands but nothing more than that. It really differs from state to state, city to city, jail to prison, it’s a broad spectrum of what can and cannot take place.

SEP: You write about the people in Kentucky who have been affected by the opioid epidemic. Can you talk about how that crisis has been handled differently than drug epidemics of the past?

Harvey: Yeah, I would say that the 1980s war on drugs — all of that legislation — literally ensured that people of color were under attack. From that alone, they were overrepresented in jails and prisons. The Anti-Drug Abuse Act of 1986 was something that really put racial minorities in a chokehold. The thinking of criminality, the idea of looking at it as something people were doing and not something happening to people. We weren’t thinking about it in the context of a health crisis. And now, we’re looking at the opioid epidemic as a health crisis. Like, “how do we fix this? How do we help people?” That was not the narrative when we had the war on drugs during the crack epidemic. It was “let’s lock all of these people up,” and I think that’s been a huge distinction.

SEP: How have companies been profiting off the increase in incarceration?

Harvey: Financial exploitation of families by the prison industry is huge. We see that in phone calls, e-mails, videos, these are all services that we on the outside are able to access quite easily. That is not the reality for people who are incarcerated. They have to pay a really high rate for these things. In Jackson, one of the families paid $6.99 for her video call that was 15 minutes. What does that mean for those families to pay that every time they want to interact with their incarcerated loved one? In some counties, it’s up to 25 dollars for a 15-minute phone call. That exists. It’s a huge industry. The going rate for hundreds of counties is 15 to 18 dollars for a 15-minute phone call. Some of these costly rates are driven up hundreds of millions of dollars by concession fees. We would call them “kickbacks.” The phone companies are paying local and state prison systems in exchange for these exclusive contracts. So, as long as they’re getting this kickback, why give them free or cheap ways to communicate?

And on top of that, we also have commissary. This is like the prison retail market. So, inside these prisons, people still need access to things. If you get a small bar of soap or if you get limited food during lunchtime or dinner, you order extra from the commissary. It’s not always that the commissary is significantly higher, but it’s high when we think about the prisoners who are paying for this. If you make four dollars a day and then you have to pay four dollars for a fungal cream, then that is exorbitant for you. Families spent $1.8 billion on commissary in a year most recently, and that’s a lot of money for families to spend. [Prison Policy Initiative found that American families spent $2.9 billion on commissary and phone calls yearly in 2017.]

I think as long as that is happening, then families will be exploited. We have to think about why it is that we can charge that. We say, to a degree, that “they can’t have cell phones” because “we don’t know what they would do with these cell phones,” but a lot of this is just financial exploitation. Private companies have found a number of ways of making sure it’s profitable. These families want to stay in touch, and if they have to go in debt trying to, that’s what you do.

SEP: Who do you think should be reading your book?

Harvey: I would say, people who are not familiar with the concept of mass incarceration and how it is impacting this country; not only people who already care about incarceration. Everyone who wants to be informed and be good citizens should be reading this book. As humans, we need to be thinking about what our country is doing, in terms of policy, that is impacting specific demographics. We need to be thinking about why it’s impacting black, brown, and poor people at such a high rate, and what that says about how we feel about those people. It needs to be read far beyond the advocates, far beyond the reformists, far beyond the directly impacted, but by those who are not familiar with what is happening but should be. We can’t continue to allow willful ignorance; I think everybody needs to demand that we have an equitable system in this country. Everyone should be reading it, and especially those who aren’t familiar with how morally bankrupt our system is.

It’s easy to give out statistics, like, “hey, 2.3 million people are incarcerated, 555,000 of those people are locked up pre-trial, which means they can’t go home because they don’t have the money,” but if you haven’t had a friend or family member face that, then you don’t understand that. So it’s easy to say that, but what does that mean? What does that look like? If I tell you a story about a young man who faces this and what that means for him, then we’re like “huh, that that’s how that works.” So I think it’s important to use narrative and storytelling to illustrate how policy is impacting people. That way, we’re able to connect to the person and understand the policy behind that.

SEP: Speaking of pre-trial, you write quite a bit about people serving long prison sentences, but we have seen jailing in the short-term increase a lot in this country, especially in rural areas.

Harvey: In Louisville, a lot of the women I interviewed were actually from eastern Kentucky. So, it’s very rural, and there’s not a lot of access to rehabilitation programs or drug or alcohol treatment that goes beyond the seven days, so they were jailed and then released to this program, The Healing Place, that allowed them to have a longer stay to really deal with this drug or alcohol issue. One of the young women in the book served 18 days, and the 18 days she served in jail impacted her heavily because while she was in jail, her children were put into foster care. Once this woman got out of jail, she figured she’d pick up her kids, but you can’t just pick up your kids once they’re in the child welfare system. She spent less than a month in jail, but once she got out she had this huge battle ahead of her, because we’re looking at the Adoption and Safe Families Act, and how it impacts families of people who are incarcerated. So, she was now up against this clock. So they gave her a case plan saying she had to complete a drug and alcohol treatment program, get a job, make visits once a week. But with the treatment program she was in, she couldn’t leave for extended periods of time to make her visits. She was in violation of her case plan because of her treatment program. So there was this conflict between whether the Department of Human Services was considering what it means for this woman and people like her who are in these kinds of programs that have a lot of stipulations and limitations, because you’re supposed to be focusing on your recovery.

So, here’s a woman who — in less than one month — her life was turned upside down because her children were taken away from her. That could accelerate her addiction, and she could lose her house, her car, her job, and then she doesn’t have anything. So, it doesn’t have to be 20 years in prison. You could be in jail for a week and lose your job. A lot of people are living paycheck to paycheck, so there’s really just one step away from their lives falling apart. One step away from no car, one step away from homelessness.

SEP: What have you been seeing in jails and prisons with the recent pandemic? Some outlets have covered the lack of response in these facilities, and the kind of crisis that could create.

Harvey: I saw that in a jail where there were more than 600 cases, they were literally writing on their windows “help us,” like, “we matter too,” crying out to the public that even if they are in there and convicted of a crime, they don’t deserve to die there because the proper precautions haven’t been taken to make sure they’re not at a greater risk to contract this virus. And we’ve seen people contracting and dying from this virus in federal prisons. There was a man who had served 44 years and he was due out this year, and he just died from COVID-19 behind bars. All of the people who work in these facilities do come back to their communities. So if you don’t think that incarcerated persons are important or valuable or that their health should be considered, think about the people who work in these facilities. This is a public health threat. Some local governments are suspending jail times for low-level violations, or reducing arrests for minor offenses. Some places are releasing pre-trial detainees. We are seeing some things happening, but it’s not happening quick enough.

Featured image: Photo by Rayon Richards.

3 Questions with Patricia Heaton

Patricia Heaton has relived moments from her own life as a mother playing a TV mom on the hugely popular sitcoms Everybody Loves Raymond and The Middle. Now the Emmy and SAG Award winner is imitating aspects of her life again in the CBS comedy Carol’s Second Act. Dressed in scrubs, she’s is an empty nester pursuing her dream of becoming a doctor. “My own four sons are pretty much out of the house,” she says, “and I was wondering what might come next. So it’s been interesting to have this experience with Carol who’s working with interns who are half her age.”

Taking on a new role in her TV career made Heaton realize the potential in all of us to find ways to change direction. That led her to write Your Second Act: Inspiring Stories of Reinvention, due in bookstores in May. “I found stories of some really fascinating people who’ve reinvented their own new lives,” she says. “I think that the book will encourage and inspire a lot of people.”

Jeanne Wolf: Why are second acts so important?

Patricia Heaton: For people whose kids have left home or maybe they’ve retired, it can be a challenge to adjust to a new way of living. I want to encourage them to look inside themselves and to see where they’d like to be in the world at this stage. The world needs all of us. As for me, I’m in Oklahoma producing my first movie. Finding so many things to learn. It’s crazy. And, very important, for a couple of years now, I’ve been a celebrity ambassador for World Vision, which provides relief and aid to children and their families in nearly 100 countries.

JW: Does your sense of humor and having built a career on being funny on television help you cope with whatever life brings you?

“Most real comedy comes from pain. You try to find humor in the troubling situations.”

PH: I think especially in the darkest part and the most difficult times, you just must see the humor and the irony in crazy things that happen. Most real comedy comes from pain. You try to find humor in the troubling situations.

JW: Do you ever think, “I can’t believe the life I’ve led as the star of those iconic TV comedies?”

PH: Every single day I feel that way. I tried to make it in New York for nine years, and I couldn’t get arrested. It’s shocking to me even now that when I came to Los Angeles I didn’t have a car or an agent or a manager. It’s miraculous that I’m sitting there today, having done all the things I’ve done.

Even with success, I think my own ego was getting in the way. I finally realized I needed to step aside and let a greater power take control. I realized I needed to be pursuing it because it’s what God intended for me to do on this planet. And once that dawned on me, I kind of let go and said, “Okay, you lead me,” and things started falling into place.

Of course, an actor never wants to stop acting. It all started when I was in second grade, seven years before I lost my mom to a brain aneurysm. I told Sister Delrina I could sing the entire Color Me Barbra album, and I did for my class. But I know the truly important things in life are your family and friends. I think about what people will say at my funeral. Will it be that you had fabulous ratings and won some big awards? Or that you were a good and kind person. I hope it’s the latter.

This is the full version of an interview that ran in the May/June 2020 issue of The Saturday Evening Post. Subscribe to the magazine for more art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

Featured image: Joe Seer / Shutterstock.com

3 Questions with Patrick Stewart

Patrick Stewart looks absolutely splendid. He smiles at the compliment. “It’s a tribute to my peasant genes.” Stewart admits that being a self-declared workaholic is part of the secret to seeming more than a little like the Captain Jean-Luc Picard from 25 years ago. Now, he’s bringing him back for CBS All Access on Star Trek: Picard in a startlingly new take on the futuristic world.

Stewart made his debut in a school play at six and has never stopped working, on screens big and small as well in theaters around the world. At 79, he can look back on a career in which he’s played nearly every Shakespearean legend and a stunning array of memorable characters in too many movie and TV shows to count, but Sir Patrick is probably most proud of being knighted by the Queen. Stewart reveals that the biggest challenge he faced in his new venture was making sure that Star Trek moved into a future which reflects changes even Gene Roddenberry hadn’t imagined.

Jeanne Wolf: You had some very strong opinions about what you wanted Star Trek fans to see before you took on the challenge of a new series, didn’t you?

Patrick Stewart: I wanted diversity. Many years have passed since the last time I was on a Star Trek set. The world is a different place. So we find our beloved Picard in a life which bears no resemblance whatsoever to his service as a Starfleet captain.

“There’s always an improvement that can be made for humankind and society.”

As for taking on a new challenge, I have never thought of retirement. Sigmund Freud said, “The two most important things in a life if you want to be happy are love and work.” I am very blessed that I have the former, perhaps in ways I’d never have anticipated. However, the work has always been a bit more negative because I’m obsessive. People have said to me, “The problem with you is that you only know how to work, and when you’re not, you don’t feel as though you’re Patrick Stewart at all.” In a sense, that is true. With acting, when I first dipped my toe into that particular creative pool, I was delighted to discover that I could spend a lot of time not being Patrick Stewart, which gave me a great deal of satisfaction.

I sometimes look back and think, How did this all come about? All I wanted to do was be on stage reciting Shakespeare and nothing else, and then suddenly I find that I had become somebody that I still don’t quite know how to be.

JW: What has shaped you both personally and as an actor?

PS: I didn’t have an idyllic childhood, although I started doing some acting at a very young age. My education was over at 15. In the society that I grew up in, you went to work after that. It was usually in a factory, mill, or coal mine. That was where most of my family, after primary school, ended up — and quite a few of them went to prison as well. I was blessed to have one significant person standing at my side, my English teacher, Cecil Dormand. He’s 96 and still doing great. We still have wonderful conversations, and he talks to me like I’m 15 sometimes. Cecil was the one who encouraged me and pushed me in the right direction. We all need someone like that.

And I inherited something from my father. Actually he was an incredible man — a soldier, the most senior noncommissioned officer of the parachute regiment. There was always optimism in the things he expressed. That’s why I felt so connected to Jean-Luc Picard, because he always looked for a better way and improvements that could be made. I’ll never forget one fan letter I got from a police officer who said he loved his job but there were days when he came home stressed and depressed, feeling there was no future at all for any of us. That’s when he’d get out a DVD of Next Generation and watch it and be assured that he was wrong. There was a better world waiting for us. There’s always an improvement that can be made for humankind and society. That, I still passionately believe in, I just think it’s going to be a very difficult few years until we get to that place again.

JW: After some years together, you married singer and songwriter Sunny Ozell. What about love and marriage; has that become simpler even though she’s half your age?

PS: Yes. In the sense that I now think I understand the importance and significance of sharing life with one other person in particular. It’s a glorious gift. The communication between two people from massively different backgrounds like my wife and I brings out in me a reassurance and happiness that, quite frankly, I never thought I would experience. So much joy. Fun doesn’t begin to describe it. Joy would be closer to the experience.

—Jeanne Wolf is the Post’s West Coast editor

This is an expanded version of an interview that appears in the March/April 2020 issue of The Saturday Evening Post. Subscribe to the magazine for more art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

Featured image: Shutterstock

3 Questions with Alan Alda

Alan Alda isn’t exactly resting on his laurels, or resting at all for that matter. He received the coveted Screen Actors Guild Lifetime Achievement Award last year, to add to his seven Emmys, six Golden Globes, and an Oscar nomination for Best Actor in a Supporting Role for Martin Scorsese’s The Aviator. Of course, none of those overshadow his rise to stardom as “Hawkeye” Pierce in the ever-popular, darkly comic ’70s TV series M*A*S*H. He’s currently playing a lawyer in Noah Baumbach’s scorching Marriage Story, now streaming on Netflix, alongside Scarlett Johansson and Adam Driver.

The star has been out front in the battle to find a cure for Parkinson’s disease. He explains, “When I first knew I had Parkinson’s, I waited a couple of years to reveal it. I finally went public because I wanted to help remove the stigma. People who don’t want to admit they have it are holding back the progress we can make to cure the disease. If you get Parkinson’s, your life is not over.”

Jeanne Wolf: You play the voice of logic and kindness in Marriage Story as an attorney acting reasonable in the unreasonable atmosphere of a breakup.

Alan Alda: I didn’t need to do any research to play a lawyer. I’ve been through a lot of lawsuits. I love a good lawsuit. I’ve sued a few of the film studios (but I’m not saying what for). I think some of them thought I was too polite and wouldn’t take them on. You know I’ve always had that nice guy image, but that’s a bum rap. I get angry like everybody else.

JW: Your father, Robert Alda, was an actor. Did he want you to follow in his footsteps?

AA: My father encouraged me by discouraging me. He said, “No, don’t be an actor, it’s a hard life,” and then he tried to get me jobs. I guess I sort of paid him back by getting him parts in several episodes of M*A*S*H. That was fun. The only advice my dad gave me about acting that I can remember is, “Your legs will get tired, so always find a place to sit down.” It’s true. If you watch me on M*A*S*H, you’ll see how often I was sitting down with my feet up on the desk.

JW: I love that you’re working as hard as ever. What keeps you going?

AA: Number one, it has to sound like fun, and it has to seem like it will be a challenge because I don’t want to keep doing what I’ve done before. It’s like walking a high wire between two buildings and seeing if you can keep from falling off. It doesn’t always have to be in front of a lot of people. I’ve gotten as much of a kick out of performing in a small theater before a couple of hundred people as 20 million on TV or in a movie.

—Jeanne Wolf is the Post’s West Coast editor

This article is featured in the January/February 2020 issue of The Saturday Evening Post. Subscribe to the magazine for more art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

Featured image: Shutterstock.com

3 Questions with Henry Winkler

Henry Winkler has bookended his long career in Hollywood with Emmy-nominated performances. He was 27 when he got his first nom for Happy Days as the Fonz. Last year, at 73, he won an Emmy for his portrayal of the narcissistic acting teacher Gene Cousineau in the hit HBO show Barry, co-starring with Bill Hader.

Jeanne Wolf: Bill Hader has said he was nervous about auditioning with you for your part in Barry because he’s such a huge fan.

Henry Winkler: If he was nervous, I was petrified. I’ve seen Bill Hader for years on Saturday Night Live. He’s brilliant. I got my youngest son, who is a director, to literally coach me. I did the best I could and I made Bill laugh, but it wasn’t a slam dunk. There were weeks and weeks of waiting, sitting on the edge of your chair. Then you get the call that they want you. I’m jumping up and down and telling everybody. Then I go, “Oh my God I just got this great role but I don’t know how to act anymore. Why did I say yes?”

JW: Maybe the most surprising turn in your career was writing children’s books with co-author Lin Oliver. Your latest is Alien Superstar about Buddy Burger, an alien with six eyes who lands in Tinseltown. You take a few shots at the world of entertainment.

HW: If an alien ends up in Hollywood, what could be stranger than that? He becomes a star, and shows both sides of fame. We want kids to know that the reality is not what they see in the pages of a glossy magazine. Being a star is demanding, interpersonal relationships are hard, there’s body shaming — all the things I have gone through in my career. When I got famous that first season as the Fonz, I hardly left my apartment for a year. In those days I never imagined myself writing children’s books. Growing up, it was hard for me to even read because I had dyslexia, which wasn’t diagnosed until years later. Since then, I’ve done a lot of work to create awareness of it. Reaching out to kids and getting them into books is probably my greatest achievement.

JW: With all you’ve accomplished, do you ever have doubts about the future?

HW: I can take anxiety to where you literally see it leaving my body in a cloud. My biggest anxiety is: will I work again? I know what it’s like because after Happy Days, no one would hire me. It was like, “Oh, he’s got talent, but he’s the Fonz.”

In my mind I’m still physically 22. But the reality is I’m grateful for every knee bend. Men my age are waiting for the phone to ring, and I got an Emmy! I think I’ve flipped the numbers and I’m closer to the actor I wanted to be at 27.

—Jeanne Wolf is the Post’s West Coast editor

This article is featured in the November/December 2019 issue of The Saturday Evening Post. Subscribe to the magazine for more art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

Featured image: Shutterstock.

An Interview with Our September/October 2019 Cover Artist Robin Moline

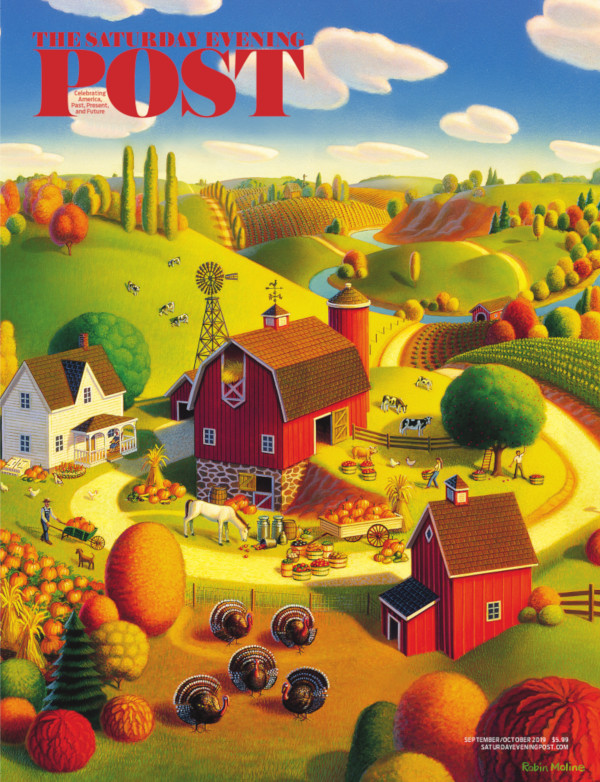

Saturday Evening Post: Can you tell us more about what inspired you to paint the image that appears on the September/October 2019 cover of The Saturday Evening Post?

Moline: This painting was originally commissioned for tapestry art, but I decided to go ahead and create an image that I could also sell for prints and as a stock image. So I basically went to town, put myself into the scene and tried to imagine what the look and the feel of that kind of day would be. The painting had to tell the story and transport the viewer there too.

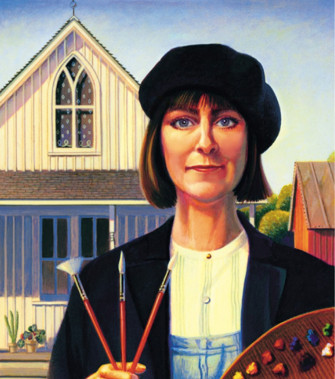

Post: You describe your style as “a surreal look with an often folksy twist.” Many of your illustrations pay homage to or are reminiscent of Grant Wood. I would describe them as “Grant Wood on acid.” What attracts you to that style of illustration?

Moline: I have heard my artwork described like that before. I’d like to think that I take Regionalism imagery and that folksy style and amplify the colors to make my artwork have a more contemporary feel. What attracted to me to this style is hard to say. I suppose first I always enjoyed painting landscapes from an early age and often they were of rural subject matter of places I’d been and farms I visited. When I first saw Grant Wood’s work I felt a connection maybe because they felt familiar and maybe because I always wanted to be in his paintings. I eventually bought a Grant Wood art book, studied it a lot, and decided I wanted to try to paint like that myself. So I did and eventually it has become what you see today.

Post: Who else are you inspired by?

Moline: There are other Regionalist artists’ work I also really love. Marvin Cone’s sensual landscapes of that same area in Iowa are spectacular. The color and movement in John Steuart Curry and Thomas Hart Benton’s work I always find inspirational. Other non-Regionalist artists that stand out are the whimsy, detail, and subject matter of Charles Wysocki paintings. Some of my early favorites were the surrealist Artists Henri Rousseau, René Magritte and Salvador Dalí and the romantic look and thermal colors palette of Maxfield Parrish. I of course enjoy a wide range of artists going back to other centuries as well. While on my honeymoon back in 1980 I saw Botticelli’s large scale paintings and was in total awe. Recently while in Italy I saw again the work of Pinturicchio and his mythological scenes and detail in Sienna’s Duomo; I could have looked at that artwork all day long. Of course there are plenty of other artists to draw inspiration from including many peers but the above stand out in the top tier.

Post: What media do you typically work in?

Moline: My traditional style is I paint on illustration board. I generally do an acrylic airbrushed underpainting then go in with fine tiny acrylic brushes to finesse the art and add detail and texture.

Post: How did you get started in your illustration career?

Moline: I pretty much decided to freelance right out of my college years at The Minneapolis College of Art & Design. I was lucky to start out when I did. There was a lot of local work and I was able to get a representative early on. In the ’90’s after I had established a more consistent style and fine-tuned my skills, I then looked for a national representative and broadened my field.

Post: How is painting for yourself different from painting for a client?

Moline: I do enjoy both. I love the challenge of working with a client and the problem solving involved, whether it be a book or magazine cover, an editorial, a poster, map, or product design. I always love seeing the end result when a client is involved because I am working with other creatives and my work gets to be woven into a bigger picture. I also don’t mind a deadline; of course the longer ones are more welcome. When I work on a painting for myself it’s hard to know when to stop, and that can be a problem. Also when I have a set client there is incentive to get the artwork done because I get paid sooner. So that’s a big motivation as trite as that might sound. Of course painting for myself I only have myself to please and I can experiment and not have a client expecting that specific look they are after based on seeing previous work.

Post: What is your favorite thing about being an artist?

Moline: Honestly being my own boss and working out of my home and not dealing with a commute is the best. Working with so many wonderful creative people I’ve met along the way and that there is always a challenge and rarely a dull moment. Being an artist has made me grateful that I have a way to express myself and that it has allowed me to expand my imagination. Hopefully through my work I can move others emotionally and intellectually and to be able to share some of my inner world and imagination.

Post: What’s the most fun thing you’ve painted?

Moline: That’s a hard one to pick over the 40 years of painting. So I’ll give you a few that achieved a few levels of satisfaction. The Farmer’s Market Stamp project stands out…I loved the art director and I had a luxurious long deadline. It was first thought that I’d be doing some of my signature landscapes, but in the end I was painting every kind of fruit, vegetable, food, and plant you might find at a neighborhood farmer’s market. It was definitely a job that evolved over time, but I enjoyed the whole process and it also included a trip for the unveiling ceremony in Washington, D.C.

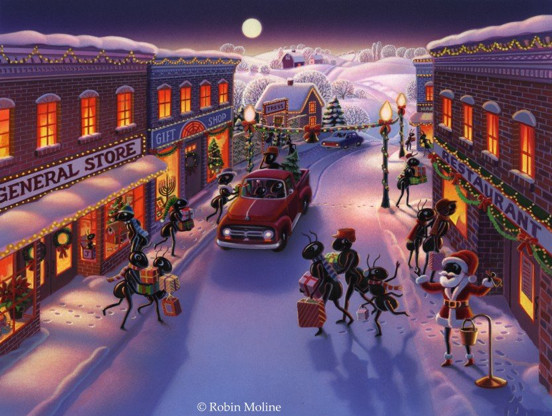

As far as landscape art goes I was lucky to work with HOK architects/engineering in the early ’90’s and did some big projects with them. The second was mural art for the new John Deere Pavilion in Moline, Illinois. The actual painting is a bit of a blur — the deadline was pretty fast considering the amount of painting involved, but the end results still please me to this day. I also fondly look back at an ongoing series I did for a high profile marketing group out in Hollywood called the Ant Farm. I created a group of ant characters for them that were pretty busy and active doing fun things mostly taking place out in L.A. Again, the clients were great to work with, too.

Post: What advice would you give to aspiring artists?

Moline: Patience and practice above all. You are not going to know your full potential, hidden talents, or fine tune your artwork right away. That takes time. Your artwork, as life itself, is an evolving process…and a gradual unveiling of yourself and your story. Don’t be afraid to experiment with different mediums and subject matter. You will make mistakes and you might disappoint those you work with now and then but you will learn from that. Don’t fear those periods of time when you don’t feel an ounce of creativity surfacing. When that happens, it will take time to observe and reflect and do whatever else you are being pulled toward…travel, read, relax and pick it up again when you are reenergized and the creative tap starts flowing again. Whatever you do don’t compare your work to others… if you are enjoying what it is you do and are growing as an artist, that is number one. Also accept that not everyone is going to like your art. Some will be critical, but if you love your work and you find a niche and even a few people love what you do as well, then you’ve made it. At that point smile and pat yourself on the back!

Post: Is there anything else you’d like Saturday Evening Post readers to know about your work?

Moline: Looking back on my career, a day that tickled me the most was when I was Googling some of Grant Wood’s work, my image came up and someone had mistaken it as his. Just last year I was asked to do a show down at the American Gothic House in Eldon, Iowa. That was another highlight of my career — to be standing in front of that house that had been parodied endlessly, and that my work that was on display inside was inspired by my favorite muse. I’ve told numerous people before that in fun I like to call myself Robin Wood. I think it has a nice ring.

To find out more about Robin and her work, visit robin-moline.pixels.com/.

Featured image: Robin Moline / SEPS.

3 Questions for Danny DeVito

After almost five decades in show business, Danny DeVito still gets a kick out of seeing himself on a movie poster. For the new live-action Dumbo, directed by Tim Burton, he’s sporting a top hat as the ringmaster of the circus that is home to the famous flying elephant. “I’m very at home in the center ring,” he laughs. “The part felt familiar because when I did Batman Returns with Tim I had a circus troupe.”

The Oscar nominee and Golden Globe winner has taken on roles of ordinary and extraordinary characters like no one else on screens big and small. He’s loveable even when what he does and says should make us cringe. Imagine encountering Taxi’s Louie De Palma in real life — especially in our politically correct environment. And then there’s Frank on It’s Always Sunny in Philadelphia: crude, rude, and funny as hell.

Now DeVito is working with Dwayne Johnson on the new Jumanji, and The Rock couldn’t help but gush about his newly minted co-star, saying, “The idea of Danny DeVito joining our cast was too irresistible.”

Jeanne Wolf: I just saw you on Michael Douglas series The Kominsky Method. Do you still go after the best parts, or do they come to you?

Danny DeVito: Both. But actors want to work. Maybe some are thinking about becoming big movie stars, but I always believed the best thing for me was to focus every day on trying to get a job. Moment to moment, you think to yourself maybe you’ll get lucky. Of course, for me, the big break was getting Louie de Palma in Taxi. You don’t know when it’s going to come, so you just want to be ready. What you live for as an actor is to get up there and be with other actors. Now I have the best gig in the world doing It’s Always Sunny in Philadelphia, which has been around a lot longer than Taxi. But every day I still call my agent and say four words: “Get me a job!”

But acting is not just a job, it’s a craft. My grandfather was a tailor. He could take a piece of cloth and make the most beautiful things. I like to think I’ve got some of that ability to take all the elements and work them into something beautiful, something that will grab people and entertain them. Also, I’ve gotten rid of my worst impulses by acting them out. It started with Louie. It’s like a license to kill. I was given this wonderfully diabolical, self-serving, self-centered character to play.

JW: Did you dare to dream as big as the films and TV shows that have made you a big star?

DD: When I was a kid I used to sit in front of the TV watching old movies and thinking I could do that but I couldn’t really tell my pals what I was planning. That would have been too tough. They would have said, “Danny what’re ya, nuts? Who d’ya think you are, Cary Grant?” So I had to keep my mouth shut. But I was learning about comedy.

My mother and father had what I guess you could call an explosive relationship. Everybody was always saying exactly what was on their mind. Sometimes, being funny was the best way to hold your own, and that can really develop your sense of humor. Now, I’ll do almost anything for a laugh. I don’t want to do any kind of dangerous stunts because I’m a chicken, but I will do anything if it is funny for the script. I’ve gotten thrown out of windows. I’ve been naked. I’ve puffed myself up in a fat suit with makeup. I’ve done everything.

JW: We’re in the middle of an immigrant controversy. Your family were immigrants.

DD: My grandparents came from southern Italy. They lived in cold-water flats in Brooklyn. My grandfather shined shoes. He didn’t have a skill. So it’s like a normal story for immigrants — coming here and not speaking English. They came because they had no money, not unlike the cases of the people from Nicaragua and from El Salvador who are coming to the border. And here we are in this big, beautiful country that has all these legends, like the Statue of Liberty, and it has all this land and is so wealthy. I would come here too. I would do whatever I could to try and get into the country.

But you can’t live in the past. What you gotta do is think of the future because what you’re doing right now is gonna be the good old days. If you sit around on your butt and don’t do anything, when you’re 90 you’re going to have no “good old days” to think about. You’ve got to do it now. You gotta get up and do something. Don’t sit around just listening to all the claptrap on television. Go out to the movies because going out to the movies is an experience in itself. Take a friend, go out to dinner. Don’t drink and drive, but have a good time.

Entertainment, that’s what we do. We are a release. You go into the movies and the lights go down and you become absorbed in the story. It’s like reading a good novel. It takes us from our reality and shows us, in our lives, something that we can hang our hat on and emulate. I like that people leave the theater and have a good smile on their faces.

An abridged version of this interview is featured in the March/April 2019 issue of The Saturday Evening Post. Subscribe to the magazine for more art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

Image Credit: Shutterstock.com

An Interview with John C. Reilly