Post Artists: John Falter Captures American Moments

See all Post Artists Videos.

Featured image: “Lunch Counter” by John Falter (SEPS)

Gallery: Heartwarming Christmas Traditions

Christmas is a season outside of time. Each holiday is new and fresh while at the same time connecting u to every other Christmas we’ve ever known. So each holiday season brings with it not just joyful moments but a generous helping of the past.

Norman Rockwell

December 25, 1948

J.C. Leyendecker

December 24, 1938

George Hughes

December 6, 1958

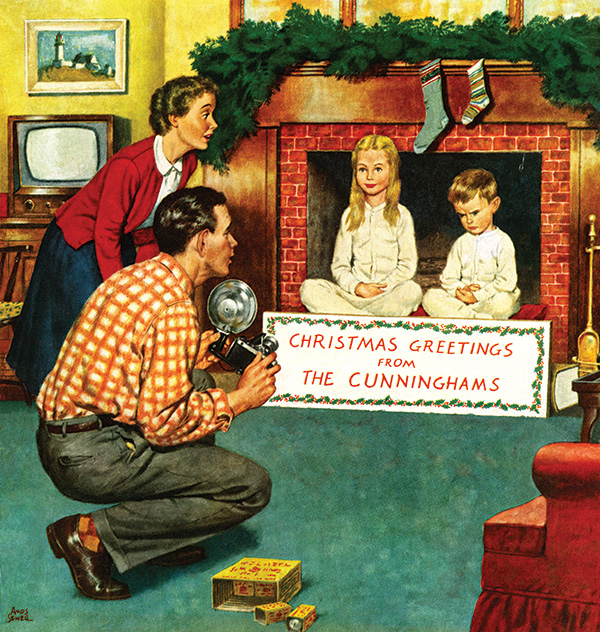

Amos Sewell

December 11, 1954

Richard Sargent

December 7, 1957

Christmas planning can be a joy, but it often veers towards comedy. In the hands of Post cover artists, the experience is presented in equal parts delight, misery, and silliness.

Constantin Alajálov

December 23, 1950

George Hughes

December 1949

Richard Sargent

December 19, 1959

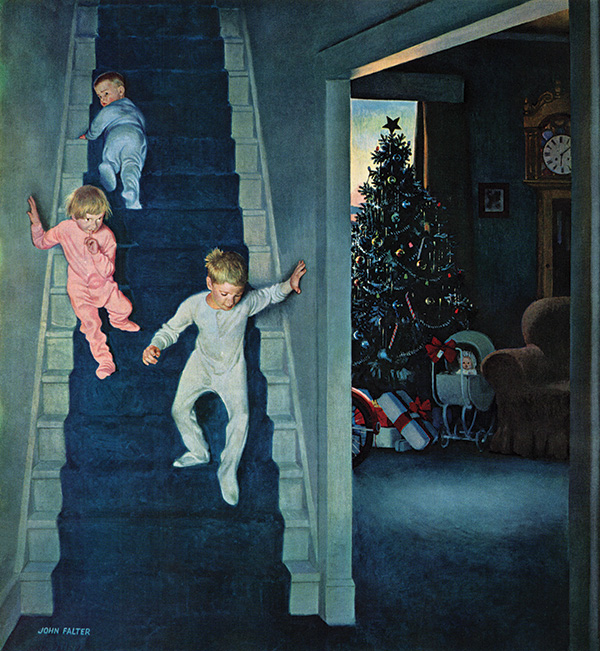

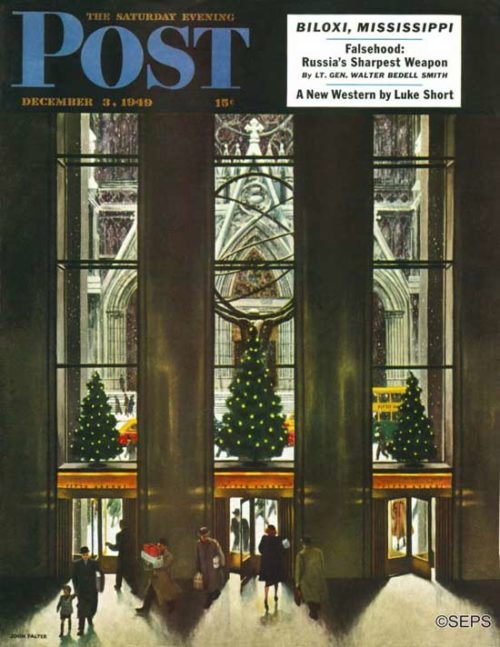

If the windup to Christmas is hectic and exhausting, John Falter’s cover reminds us what an amazing spectacle the holiday is to children. In their cautious, pajama’d descent down the staircase at first light, one can almost feel their joy that, after weeks of longing and anticipation, the magical day has finally arrived.

John Falter

December 24, 1955

Ben Kimberly Prins

December 27, 1958

This article is featured in the November/December 2019 issue of The Saturday Evening Post. Subscribe to the magazine for more art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

Featured image and artwork: SEPS.

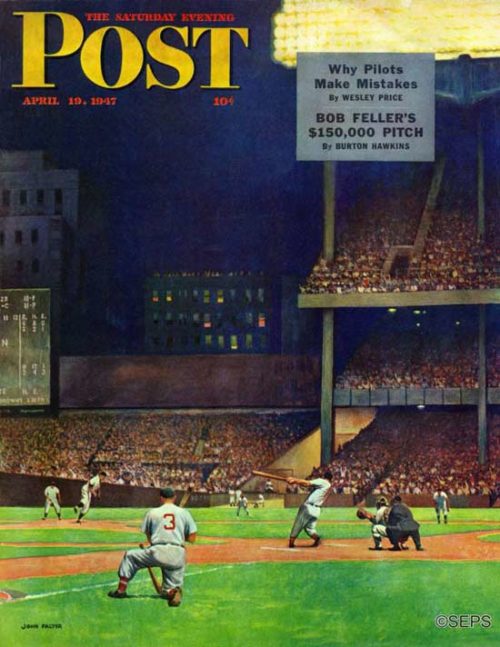

Cover Collection: Baseball

From luminaries like Stan the Man and Yogi Berra, to kids playing sandlot ball, The Saturday Evening Post knew no equal when it came to great baseball covers.

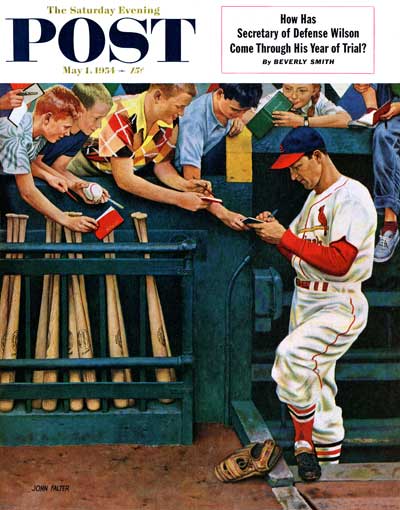

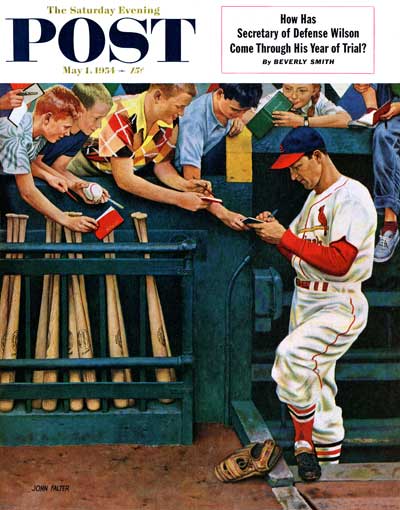

John Falter

May 1, 1954

Not only did these St. Louis kids have to miss school (awww!), they had to sit and pose with Stan the Man Musial. What a rough life. The lucky youngsters wound up with forty Musial autographs. “Wow!” one said in awe. “Will we clean up selling these at school!” We’re sure at least one of them has wished he’d kept it.

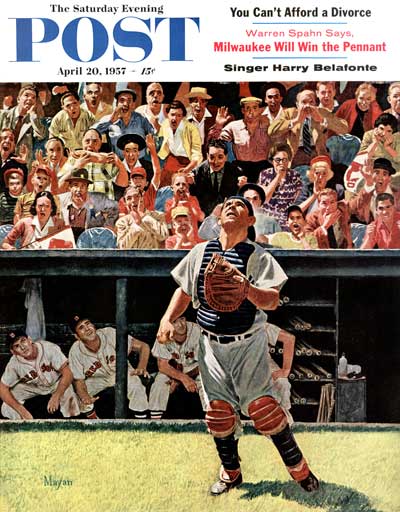

Earl Mayan

April 20, 1957

Who doesn’t love Yogi Berra? Long before he became famous for maiming the English language, Berra was catcher for the New York Yankees. Artist Earl Mayan got him to pose in Yankee Stadium for this cover. Love the fan faces! The editors informed us they were friends of the artist and “were real nice-looking people till he asked them to look like baseball fans.”

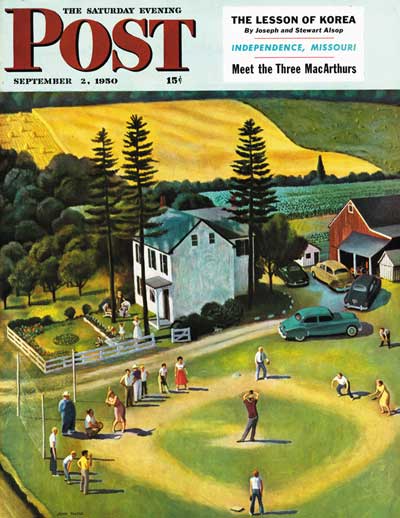

John Falter

September 2, 1950

While we admire the pros, there’s nothing like a family baseball game. It’s 1950 and Uncle Baldy can’t decide whether to pitch or throw to Aunt Sally in the yellow dress on second base and catch the guy out. We have to say Aunt Martha’s batter’s stance is interesting. The editors speculated that the umpire was selected “because he has a natural chest protector”. Well, a natural belly protector, anyway.

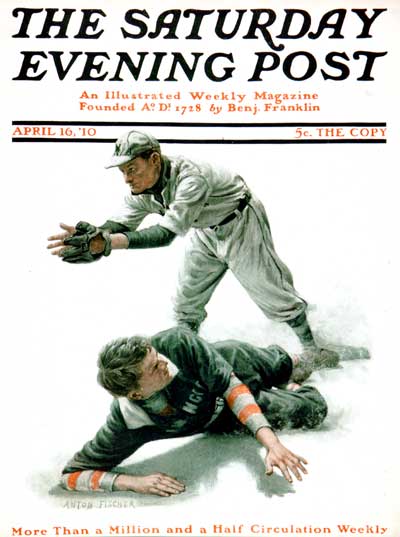

Anton Otto Fischer

April 16, 1910

It’s no surprise that they played baseball in 1910, as we see in this cover. What surprised us was the artist – none other than Anton Otto Fischer. Mostly famous for his masted ships rolling over foaming waves, Fischer also was great at painting people. This slice-of-landlubber-life captures the action perfectly. Interesting catcher’s mitt!

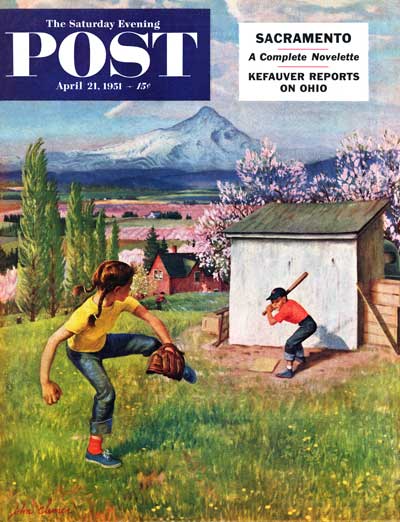

John Clymer

April 21, 1951

Artist John Clymer was known for his beautiful landscapes. Sure, he manages here to paint Oregon in all its spring glory, pink blooms, Mount Hood and all. But the eye is drawn here to the fine pitching form of Miss Pigtails and the concentration of the batter. The trees may be budding and the grass greening, but kids’ thoughts turn to baseball. It must be spring!

Descriptions by Diana Denny.

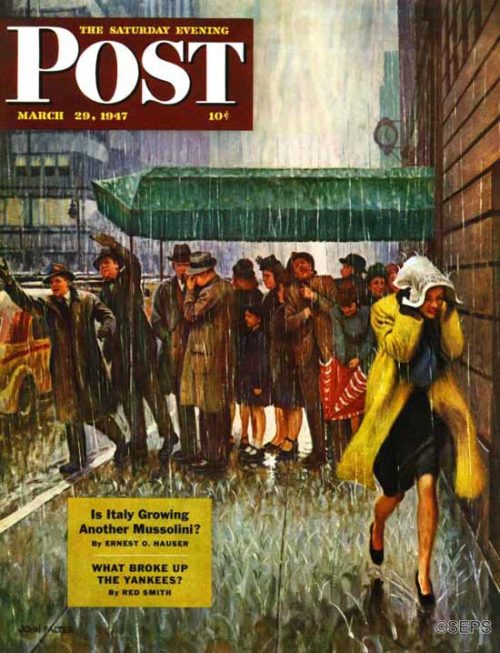

Cover Collection: March Winds

Whether it’s warm and balmy or frigid and sleeting, the March winds do blow! Here are a few covers showing that this month definitely comes in like a lion.

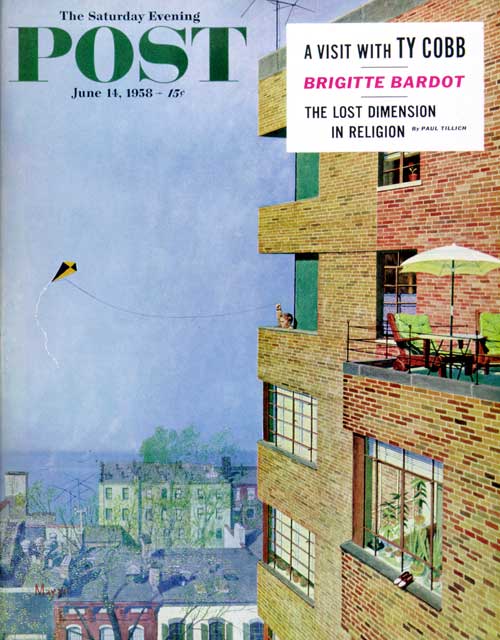

Earl Mayan

June 14, 1958

Post cover artists loved initiative, and who shows that better than the youngster in this 1958 cover? Lacking a green field to run in, the boy flies a kite from his hi-rise balcony. He might envy the kids with room to run, but those kids could envy a heck of a launching pad.

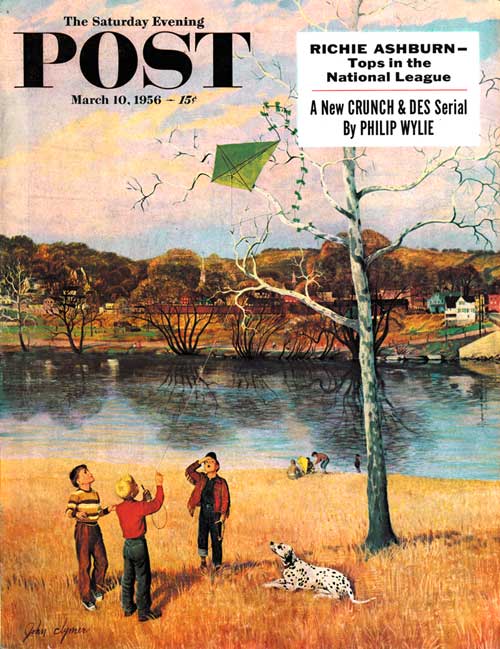

John Clymer

March 10, 1956

Having less luck kiting are the boys from this March 1956 cover. Now this is a pickle. How are those boys going to get the kite out of the tree? Does this remind anyone of Charlie Brown and his “kite-eating tree”?

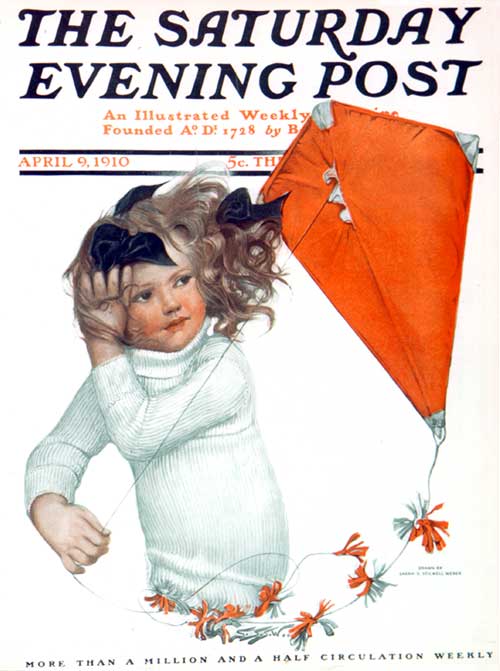

Sarah Stilwell-Weber

April 9, 1910

This pretty lass may be having a bad hair day but a great Kite Day! This is one of the many beautiful Post covers by Sarah Stilwell-Weber that depicted charming children doing everyday things.

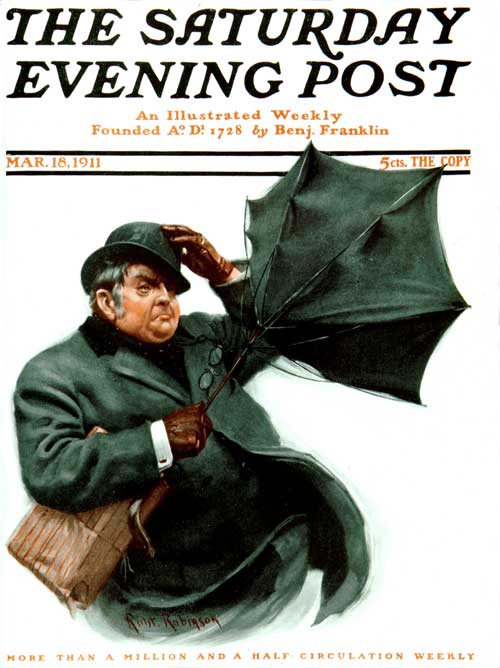

Robert Robinson

March 18, 1911

Holding on to your hat and umbrella at the same time is tricky in high winds. Everyone has had the “inside-out” umbrella experience at one time or another, and this gent from a 1911 cover shows us how frustrating it can be. Do you know what’s really frustrating? That the danged umbrellas still do this!

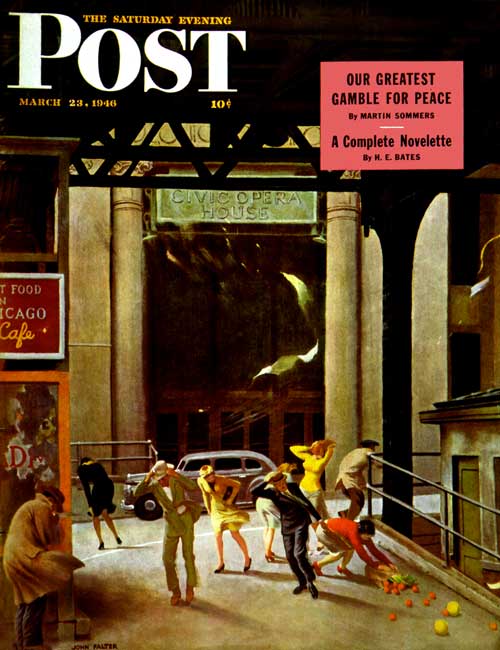

John Falter

March 23, 1946

They don’t call it the “Windy City” for nothing. In this March 1946 cover, the wind is howling down the Chicago River and creating a wind tunnel in front of the Civic Opera House. Hats and skirts are in serious danger, not to mention the poor lady trying to hold on to a bag of groceries. Talk about a bad hair day.

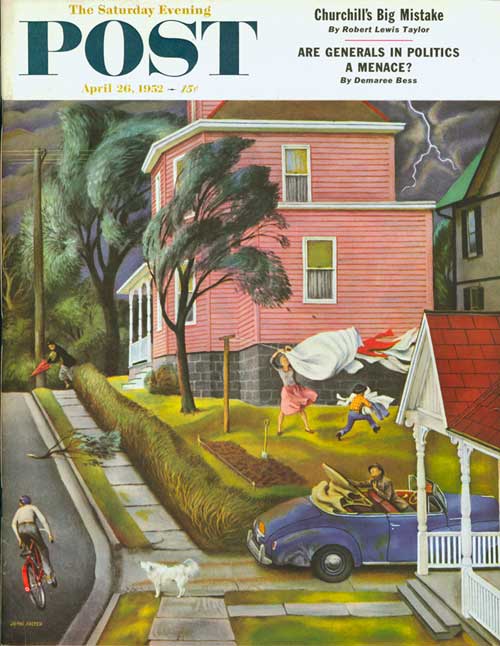

John Falter

April 26, 1952

The March winds blow! Artist John Falter went to a small town in the Midwest for this 1952 cover of big storm brewing. The trees are practically bending over, a woman and child are rushing to get the laundry off the line, and a man is putting up the top on his car (quickly!). The panic even seized the white dog in the foreground, who just rears his head back and howls.

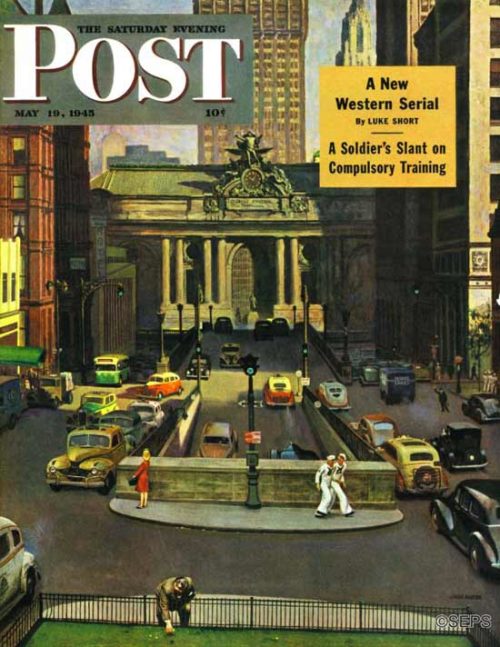

Cover Collection: Tremendous Trains

Whether you’re a die-hard train buff, a transportation geek, or merely a weary commuter, trains have long played a major role in American life. These covers — from as early as 1901 — reflect our love affair with locomotives.

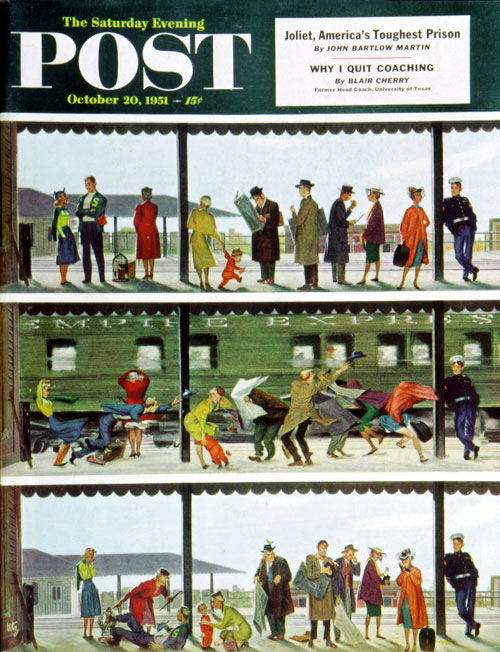

Thornton Utz

October 20, 1951

The top panel of this painting by Thornton Utz shows a well-dressed group of commuters waiting for the Empire Express. Notice the lady in red on the near left with her caged canary. Scene Two: Skirts and hats are flying as the Express roars by. The poor kid on in the letter sweater crashes into the birdcage. The third panel shows a disheveled lot, to say the least. Do you see what happened to the befuddled canary?

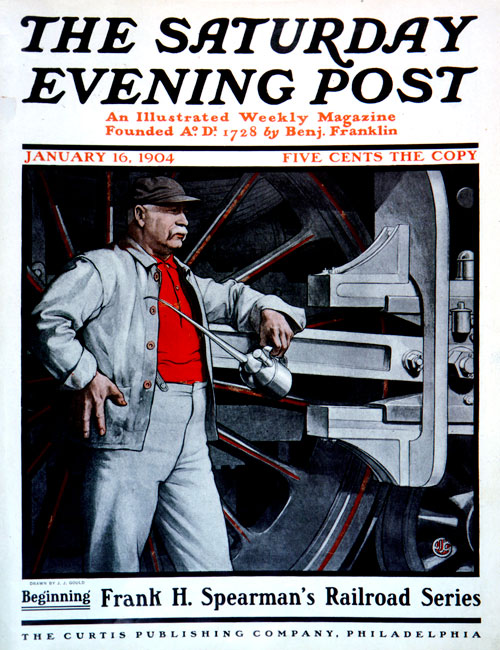

J.J. Gould

January 16, 1904

Train buffs love this turn-of-the-century railroad engineer. Standing by the mighty mechanical monster he conducts, he poses for artist J.J. Gould.

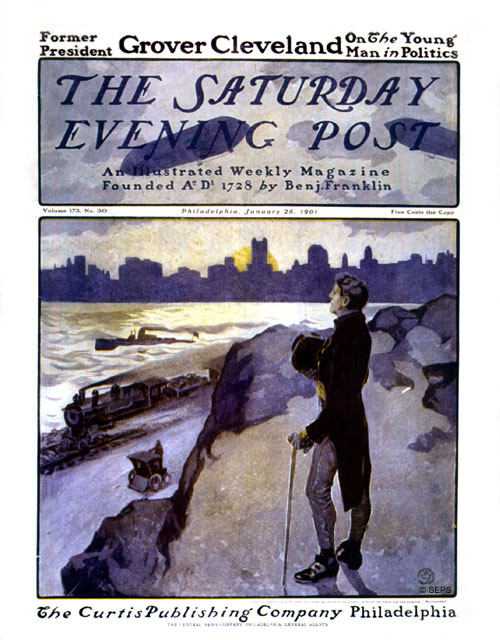

George Gibbs

January 26, 1901

As far back as 1901, trains have graced our covers. Horseless carriages, ships and trains – what will they think of next? A cityscape in the background completes this bow to modernity. The quote below the cover art says: “Bowing respectfully to the past, and rendering justice to the present, we salute the future and true progress. – Montalembert”.

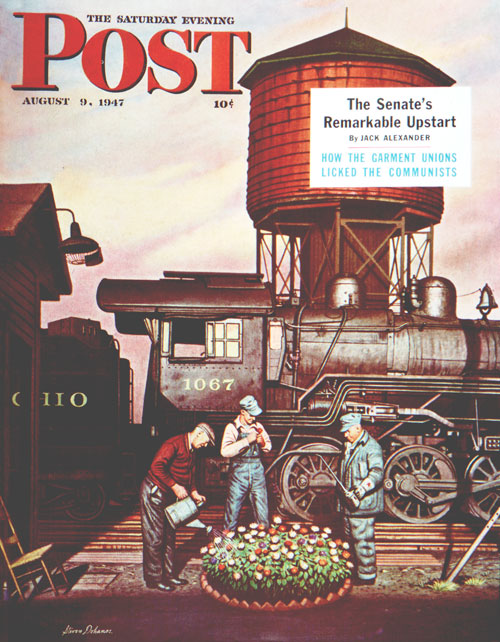

Stevan Dohanos

August 9, 1947

We love this cover by artist Stevan Dohanos from 1947. The editors noted that the artist had actually worked on the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad for a few years. “He checked loads and tracks, beginning a ten-mile hike at 6:30 every morning. He came to think highly of the switchyard men, because in their shacks he could get warm.” Dohanos painted this in his hometown of Lorain, Ohio.

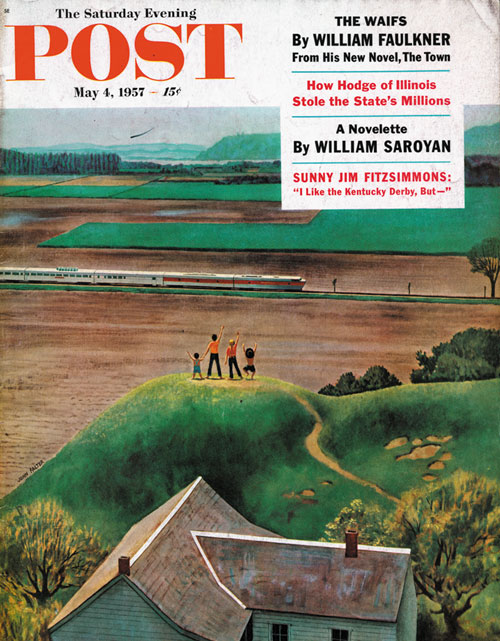

John Falter

May 4, 1957

John Falter, when a child, used to listen to freight trains chugging up a nearby hill and worry about whether they’d make it. Our scene is Missouri, the Missouri River and Kansas beyond. This time we are in Missouri, looking at Kansas in the distance. This time the kids are waving clear across the river to the train. Or maybe they just know somebody in Kansas to wave to.

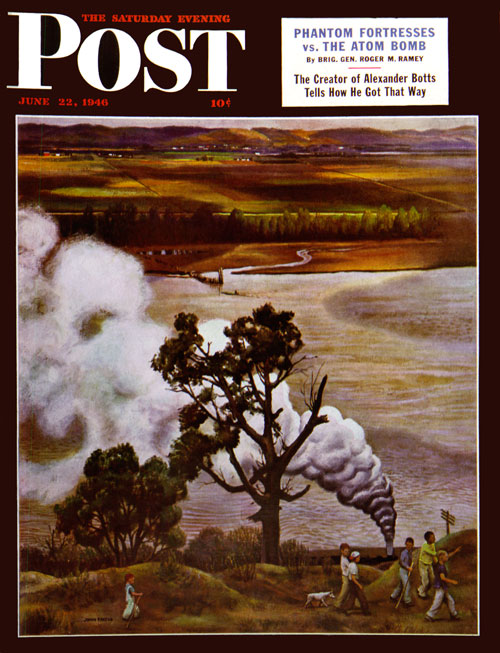

John Falter.

June 22, 1946

Artist John Falter did 129 Post covers, and this is a good example of why. Belching smoke along the mighty Missouri River, this steam engine doesn’t warrant a glance from the boys walking by. They also are probably unaware they are using a route once used by Lewis and Clark. You are in Kansas, looking over into Missouri in this one.

Descriptions by Diana Denny.

News of the Week: Failed Resolutions, Big Asteroids, and the Right Way to Make Snow Cream

Lose Weight! Exercise! Save Money!

So here we are at the end of January. Dumped your New Year’s resolutions yet?

According to one study, 80 percent of all resolutions fail by February. If you assume that number is a little on the high side, even 60 percent would still be a big number. I would guess that a lot of the failure isn’t because people are weak and don’t have willpower; it’s because they make unrealistic, vague resolutions (“I’m going to lose weight!”) instead of smaller, more concrete ones (“I’m going to stop eating cupcakes for dinner!”). I also think a lot of people don’t actually make a decision to stop their resolutions; they just forget about them or organically fall into old habits.

I’m happy to say that I’m still holding firm with my resolutions, which will remain a secret, because when February rolls around and I’ve abandoned them I can deny everything.

2002 AJ129

I don’t want to alarm anyone, but there’s a 0.7-mile-long rock traveling 67,000 miles an hour and it’s heading toward Earth.

The asteroid, with the catchy name 2002 AJ129, is going to pass really close to us on February 4. It will come within 2.6 million miles of Earth, and NASA, which has declared the asteroid “potentially hazardous,” says that’s actually too close for comfort. Luckily, it’s not going to hit us or cause any other problems.

Here’s what NASA has for a plan if an asteroid is going to make a direct hit. It’s not incredibly comforting, but at least it doesn’t involve calling Bruce Willis.

Forgot Your Password? Click Here

In other near-apocalyptic news, remember a couple of weeks ago when the state of Hawaii sent out a false warning that missiles were headed toward the Aloha State? This week, it was revealed that the reason why it took Governor David Ige a while to correct the error on social media was because … he forgot his Twitter password. Other officials (and even ordinary citizens) had already tweeted a correction by that time, but it still took 38 minutes for an official correction to go out.

By the way, the lesson from this isn’t “Officials should remember their Twitter passwords,” it’s “Officials shouldn’t rely on Twitter to tell people of a possible nuclear war.”

RIP Bradford Dillman, Ursula K. Le Guin, Dorothy Malone, Naomi Parker Fraley, Hugh Masekela, and Connie Sawyer

Bradford Dillman was a veteran actor who appeared in movies like Compulsion and The Way We Were and many TV shows, such as Court Martial, Dr. Kildare, and Murder, She Wrote. He died last week at the age of 87.

Ursula K. Le Guin was an acclaimed fantasy and science fiction writer known for such works as The Left Hand of Darkness and the Earthsea series of books. She died Monday at the age of 88.

Dorothy Malone played the mother on Peyton Place and won an Oscar for her role in Written in the Wind. She also appeared in movies like The Big Sleep, the Dean Martin/Jerry Lewis comedy Artists and Models, and Basic Instinct. She died last Friday at the age of 92.

It was revealed in 2016 that Naomi Parker Fraley was the real model for Rosie the Riveter, the iconic, strong woman seen on WWII posters by artist J. Howard Miller, even though other women made the claim over the decades and confused everyone. She died Saturday at the age of 96.

Here’s the equally famous Norman Rockwell Rosie the Riveter cover from the Post, which featured another Rosie, a 19-year-old phone operator from Arlington, Vermont, named Mary Doyle Keefe. During the war, Rockwell’s painting and his “Four Freedoms” toured the country raising money for war bonds.

Hugh Masekela was an influential jazz musician and anti-apartheid activist from South Africa known for many solo albums, playing the Monterey Pop Festival in 1967, and touring with Paul Simon for Simon’s Graceland album. He died last week at the age of 78.

You’ve seen Connie Sawyer dozens of times on TV and in movies, even if you didn’t know her name. She didn’t start acting until she was in her 40s (she is often credited as “old lady”) and appeared in everything from The Andy Griffith Show, Seinfeld, and The Office to films like When Harry Met Sally, Out of Sight, and Dumb & Dumber. She died Sunday at the age of 105.

The Best and the Worst

The Best: My favorite story this week has to be about Clarence Purvis, who has lunch with his wife every single day. You say that doesn’t sound too special? Watch Steve Hartman’s On the Road segment below and you may think differently.

The Worst: Nielsen has stopped using paper diaries to gather its ratings information. Now, you may wonder why they didn’t stop using paper diaries a decade or more ago in this age of computers, but I was happy to see that they lasted this long. I’m sure no one else cares about this, but I’m a little sad that yet another paper thing is going away (paper can also be used to keep track of your Twitter password).

I’ve never met a Nielsen family before (and I bet you haven’t either), but my family was an Arbitron family for a week when I was a kid. They were another TV and radio ratings company. We got a paper diary in the mail and since I was the one who watched the most television, my mom told me to keep track of what we watched. I’m pretty sure I just put down all of my favorite shows, whether I watched them that week or not, because I didn’t want them to get canceled.

This Week in History

FDR Begins Fourth Term (January 20, 1945)

The inauguration for Roosevelt’s fourth term was a more low-key event than usual because of World War II. The ceremony took place on the White House’s South Portico lawn.

Roosevelt died just three months later and was succeeded by Harry Truman.

Apple’s “1984” Commercial Airs during Super Bowl (January 22, 1984)

Most people think the commercial that introduced the Macintosh computer aired only once, during the 1984 Super Bowl. However, it actually aired one other time, on a local TV station in Twin Falls, Idaho, a few weeks earlier — on December 31, 1983, so it would qualify for the year-end awards.

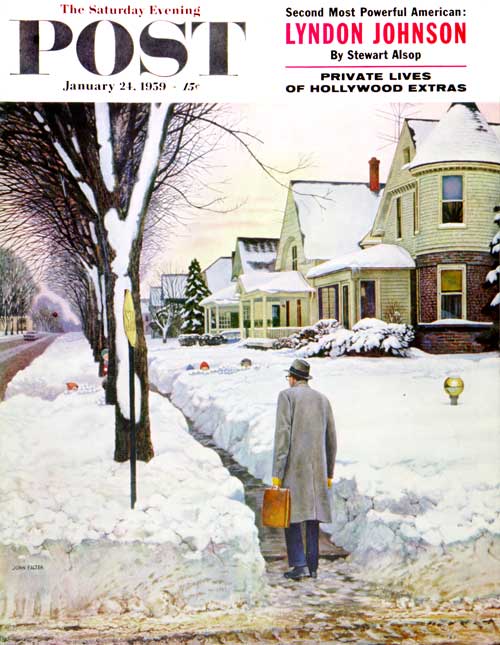

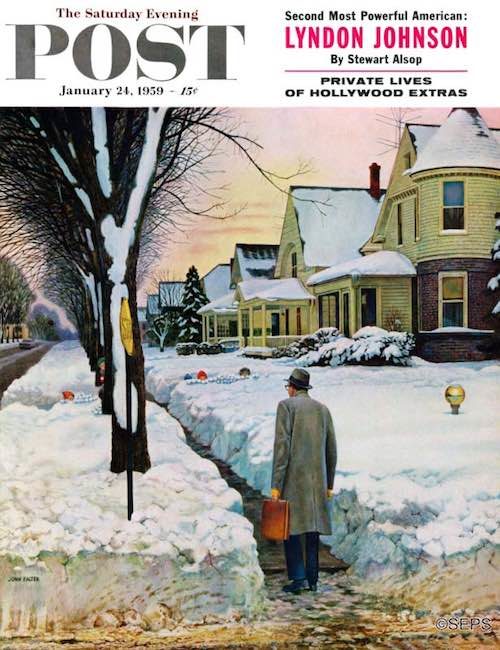

This Week in Saturday Evening Post History: Snowy Ambush (January 24, 1959)

John Falter

January 24, 1959

This cover by John Falter is one of my favorites, even if I didn’t understand what was going on until I saw the picture in a larger size (and even then it’s brilliantly subtle). There’s a reason the man with the briefcase is hesitating before going down the sidewalk, and it’s not fear of slipping.

How to Make Snow Cream

The Falter cover above features a lot of something you need to make the Southern and Canadian dessert known as Snow Cream: snow. No, not something that looks like snow or has the same consistency as snow; I mean actual snow that you probably have in your backyard or on your front stoop this very moment. This recipe includes sweetened condensed milk and vanilla.

I don’t know if I’m going to make it anytime soon, but you can’t help but love a recipe that includes as an ingredient “8-12 cups of fresh, white, new-fallen snow.”

Next Week’s Holidays and Events

60th Grammy Awards (January 28)

Neil Diamond, who this week announced that he was going to stop touring because he has been diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease, will receive this year’s Lifetime Achievement Award. It airs Sunday at 7:30 p.m. on CBS.

National Puzzle Day (January 29)

To celebrate the day, maybe you can try to crack these puzzles from the January 18, 1873, issue of the Post. Or maybe try to figure out copy editor Andy Hollandbeck’s Logophile Language Puzzlers. I just want to know why Diane stole a stereo.

Cover Collection: Winter Mischief

The days are short, but that doesn’t mean a shortage of fun! The mischievous kids featured on our vintage covers know how to make the most out of a fresh snowfall.

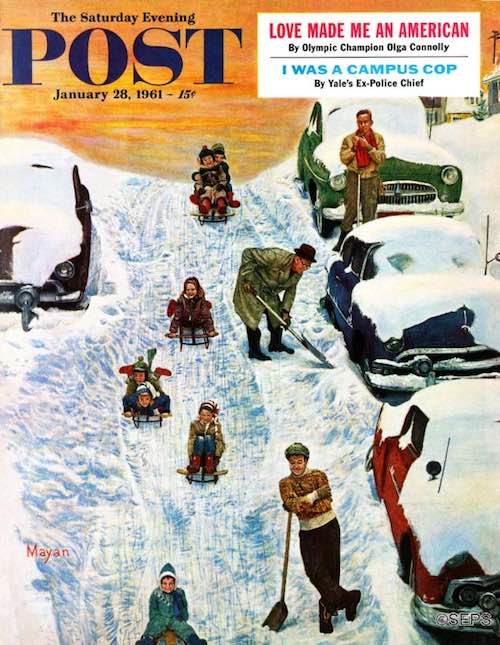

Earl Mayan

January 28, 1961

A blizzard zeroed in on Icicle Avenue last night, and this morning—gangway!—the sleds are taking over. This is the sort of weather that makes a person appreciate the sled’s advantages over the automobile. For instance, a sled doesn’t need antifreeze or windshield scrapers. There are no speed or age limits for sledding. Sleds are easy to start, even on the coldest mornings. (Especially on the coldest mornings.) You can drive a sled no-handed, and if you run into a snowdrift, why, what could be more fun?

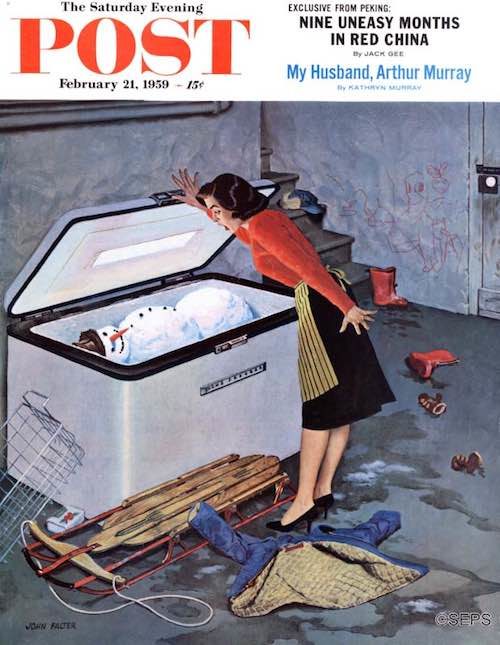

John Falter

February 21, 1959

For a split second mother thought she saw a real man lying there, stark and grinning. Readjusting her senses (mothers get to be fast readjusters), she thought, Oh, come now, one doesn’t fin d real men in freezers, does one? This is a snowman, I fear. Next thing on the agenda is to remove Mr. Smiley from his mausoleum. As mother icily summons her son and they messily lug sections of Smiley out the basement door, mother can reflect upon how funny this will seem to her week after next. Alternate plan: artist John Falter says there is a pile of displaced freezer food off stage at the left; why not lug that outdoors to keep cool and save funny Mr. S. for papa to enjoy, and remove, when he comes home? In that case, papa could reflect that a father’s work is never done

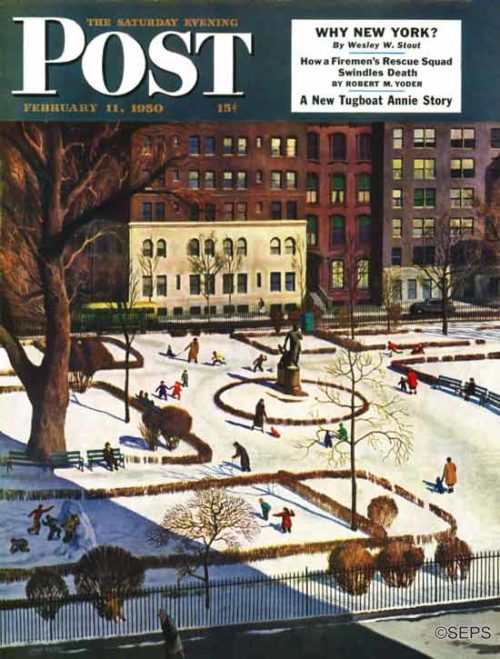

John Falter

January 24, 1959

This hard working man’s tactical problem is whether to cross the street in a flanking movement, or charge the foe and take what is coming to him, which is plenty. What would artist John Falter himself do? He says, “This scene (except for that ornamental ball, which I contributed) is a pleasant, typical Midwestern town I recently visited, named Bad Axe, Michigan.” He says, “I would charge the foe. I think.”

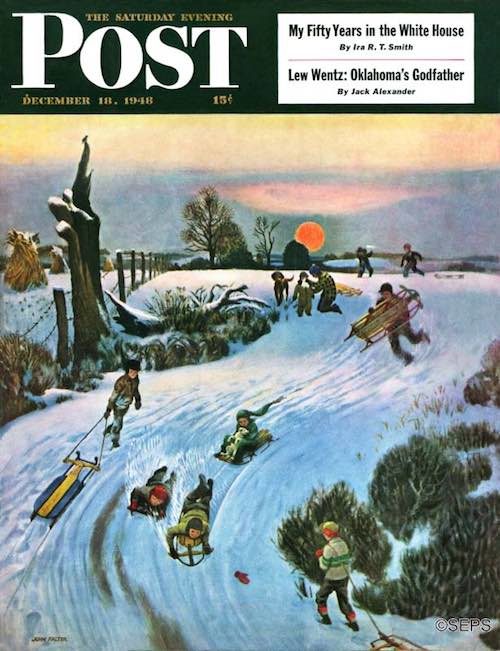

John Falter

December 18, 1948

John Falter’s sledding hill is an imaginary one he designed as a boy, long before he had any idea of becoming an artist. Where he grew up in Nebraska, the countryside was fairly flat. When Falter was the age of some of the boys in his picture, he used to imagine a hill like this one—steep enough, long enough (although you can’t see that part) and with a sporting curve near the start of the runway. He got around to painting the scene last fall while visiting Atchison, Kansas, when the temperature was ninety. The blue-and-tan sled belongs to a boyhood friend—and the friend’s son. Falter recalled it from his own childhood; it was still in good shape.

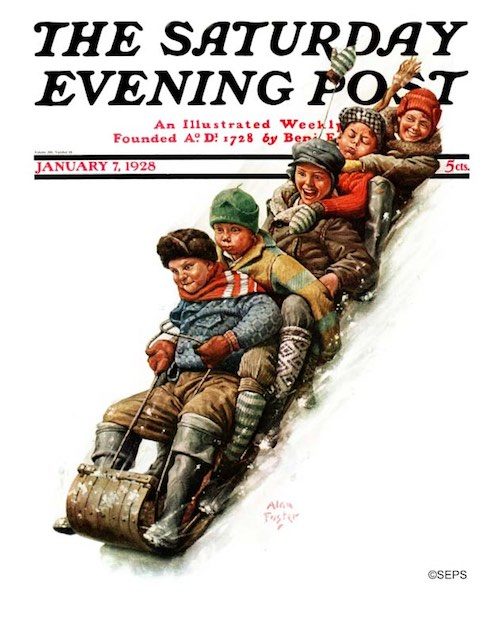

Alan Foster

January 7, 1928

Why sled alone when you can quintupple the fun? Many of Alan Foster’s 30 covers for the Post were joyful and Rockwellian in nature: kids playing sports, going on a hayride, or getting in trouble in school…or making the most of a snowy day. About three-fifths of these kids seem to be having a blast; the others aren’t so sure.

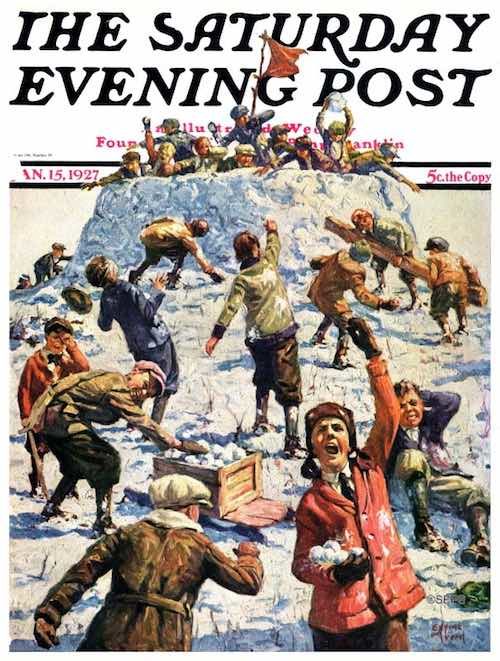

Eugene Iverd

January 15, 1927

Based on this tumultuous snowy scene, it’s unsurprising to find out that this artist grew up in Minnesota. George Erickson, who painted under the “brush name” Eugene Iverd, was one of the best-known illustrators in the 1920s, painting for Campbell’s Soup and The Saturday Evening Post. This particular painting reminds us of Lord of the Flies, even though Golding’s book wasn’t published until 1954, 27 years later. (Maybe Iverd’s painting inspired him.)

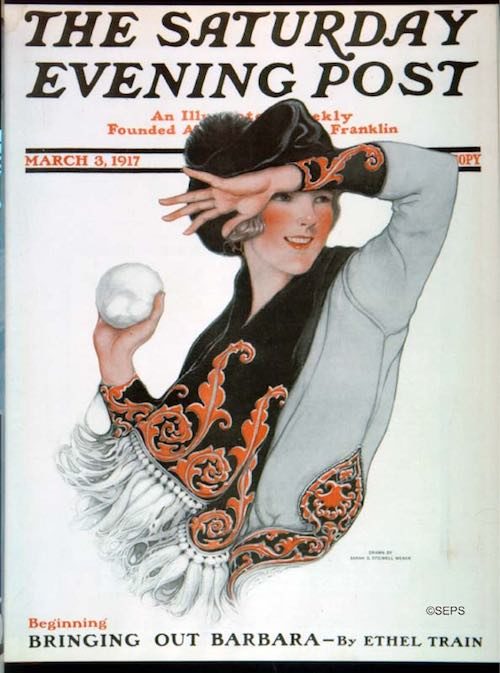

Sarah Stilwell Weber

March 3, 1917

Artist Sarah Stilwell Weber was particularly adept at creating movement and flow that gave the impression of coming and going. You had the distinct impression that the subject would dance off the page in the next moment (or nail you with a snowball). She was one of the first female cover artists for The Saturday Evening Post, completing her first cover in 1904.

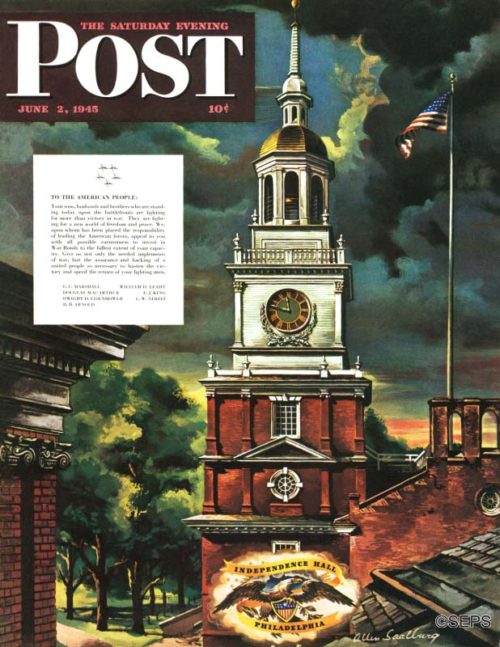

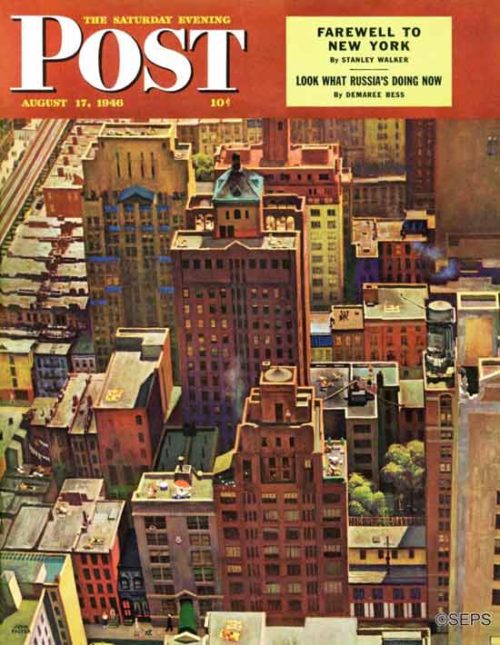

Cover Gallery: Summer in the City

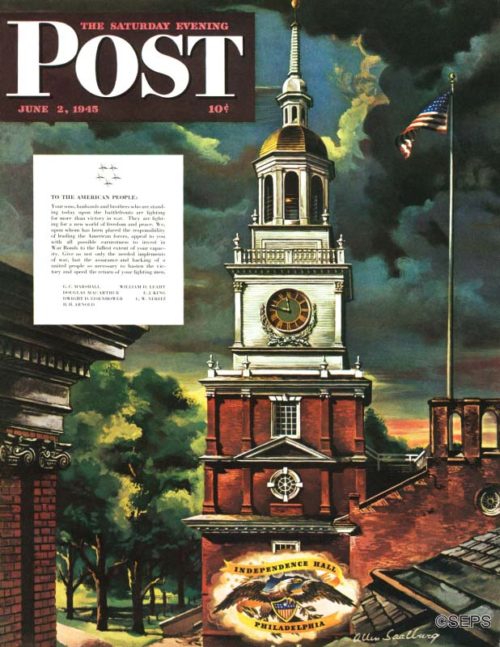

Allen Saalburg

June 2, 1945

Independence Hall, more than any other structure, is a symbol of American perseverance and love of liberty. Saalburg’s painting is a view of Independence Hall looking west. The building at the left is The American Philosophical Society, The Post’s original offices were directly behind the trees in the left foreground.

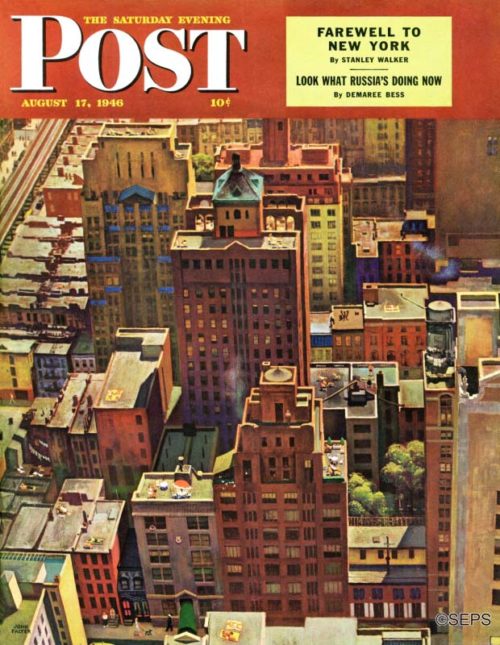

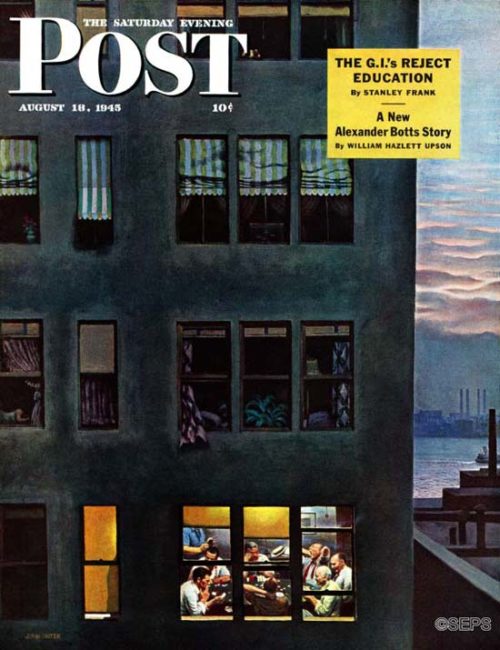

John Falter

August 17, 1946

This 1946 view is from the fifty-fourth floor of the Chrysler Building, looking south. There were sun bathers on almost every roof, stewing, frying and boiling in the early afternoon sun.

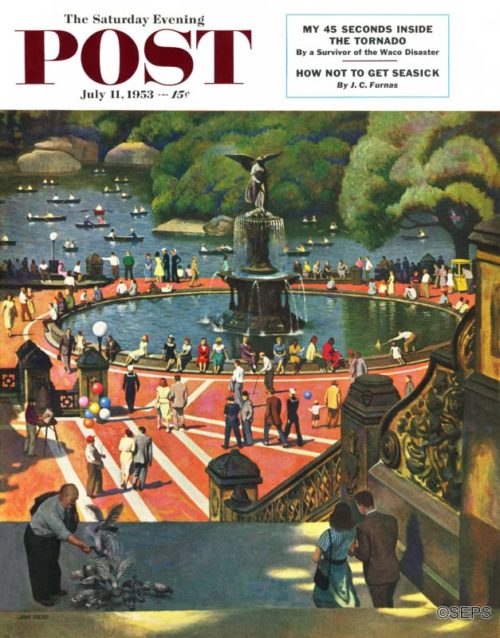

John Falter

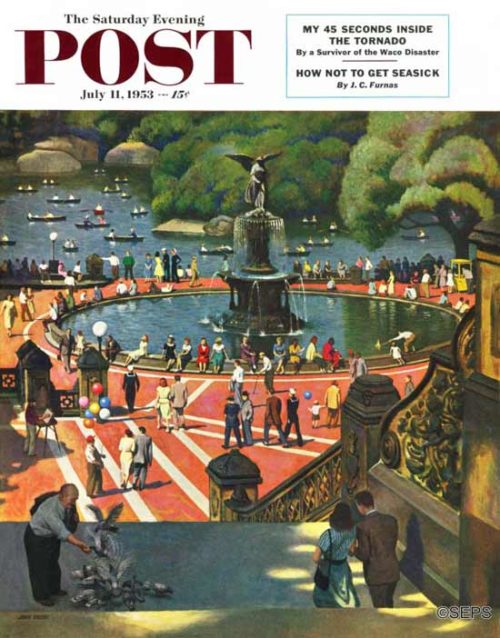

July 11, 1953

In New York’s famous wilderness, Central Park, you can hike, boat, bicycle, ride horseback, woo a wife, climb small mountains, get lost in small woods, and on the zoo trail meet many wild animals including people who make faces at monkeys. If you don’t think New Yorkers get more exercise than country people, buy some liniment and see how far you can trudge in the park without crying, “Help! Taxi!”

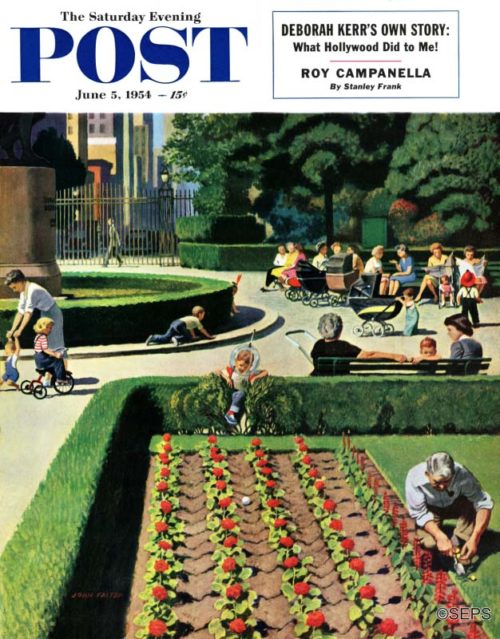

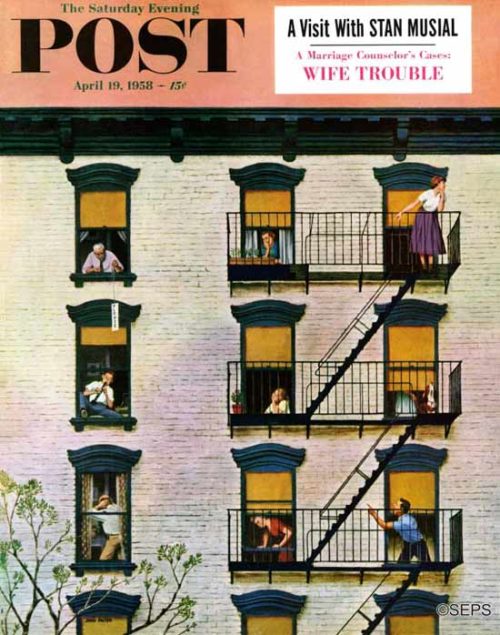

John Falter

June 5, 1954

Down out of the city’s cubbyholes come the inhabitants to enjoy some fresh air and automobile fumes. On second thought, ignore that glum remark, for actually these folks are having a swell time.

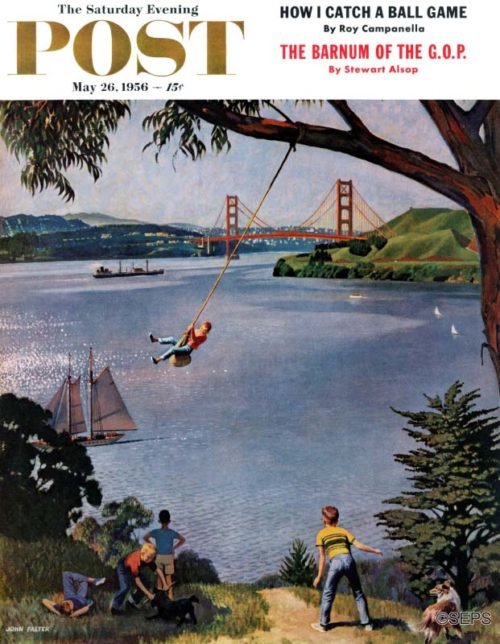

John Falter

May 26, 1956

When artist John Falter was risking his boyhood, he used to take off on a bag swing from the roof of a shed, part of his joy being to see if he could avoid demolishing his bones against the shed on the way back. Recently when Falter was strolling along Belvedere Island, admiring the grace of Golden Gate Bridge across the azure bay, he happily discovered that modern kids still relax in the mellow old hair-raising way.

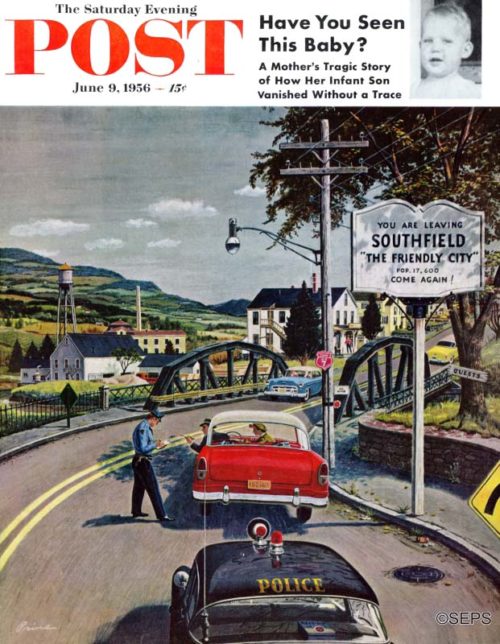

Ben Kimberly Prins

June 9, 1956

See the sociable traffic officer of Friendly City chatting warmly with strangers from a distant clime. The amiable man has even got out of his car to ask them their names and where they may be from. Will he hospitably invite them to pause awhile and be personally greeted by an official of the municipality? What is he writing for them—a complimentary ticket to the policemen’s ball? In any event, the travelers in Ben Prins’ genial scene will always carry an emotion in their hearts for Southfield, and if they ever return, will pass through at greatly reduced speed, the better to enjoy the changing beauty of its traffic lights and the curving artistry of the paintings on its pavements—and, to be sure, the better to see whether their old friend in blue is still there.

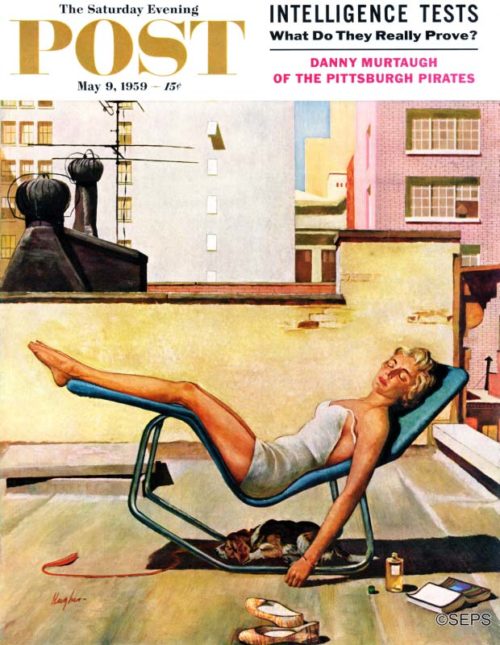

George Hughes

May 9, 1959

The day is Sunday, and this is a midtown Manhattan beach scene. As our fair lady enjoys a exposure to sunbeams, she should take care lest it degenerate into erythema solare, an inflammation of the skin.

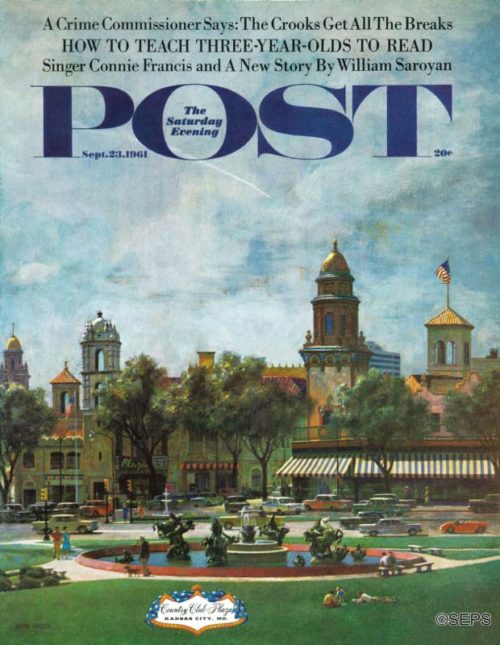

John Falter

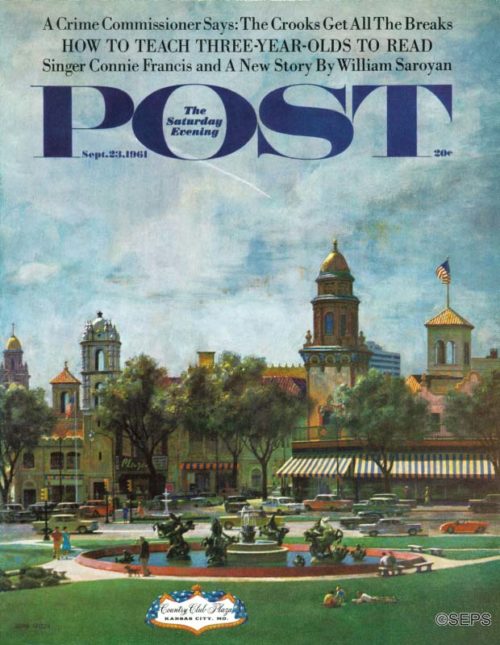

September 23, 1961

Our cover scene is in Kansas City, “the gateway to the Southwest,” and you are looking at the intersection where U.S. 50, gateway to the Country Club Plaza shopping center, crosses J. C. Nichols Parkway. This elegant community of shops was conceived and built by Jesse Clyde Nichols (1880-1950), to whom the fountain in the foreground is a memorial. The scene appealed to artist John Falter because the Old World architecture seemed to symbolize our nation’s roots—which is not to deny the notion expressed by lyricist Oscar Hammerstein in Oklahoma! that “everything’s up-to-date in Kansas City.”

Cover Gallery: Tee Time

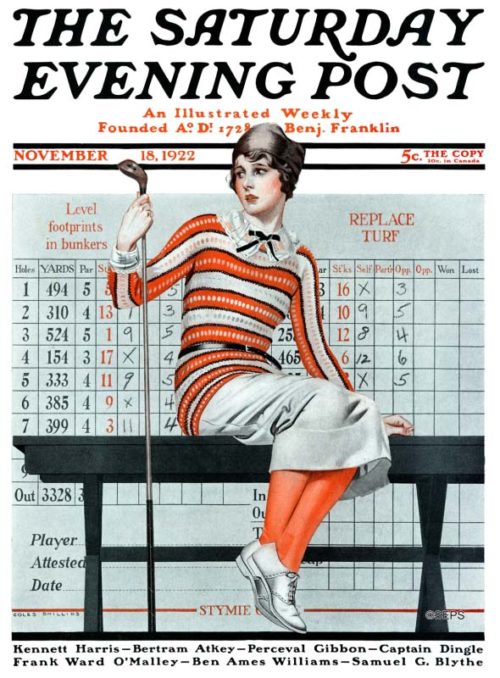

Coles Phillips

November 11, 1922

Coles Phillips began drawing when he was just six years old. Phillips caught his big break as an artist after drawing only the ankles and feet of a person’s body while working at an “assembly-line” advertising firm. His depictions were so detailed that national companies wanted to identify him. Phillips is now recognized as the singular artist of his generation who invented the “fade away” style. His models, like this first-time lady golfer, brought such an elegant grace to the twentieth century’s rising tide of wealth and parties.

Charles A. MacLellan

September 22, 1923

Charles A. MacLellan started creating art for the Post during a time when narrative illustrations dominated the covers. His most memorable covers were those with children, typically boys. Often these boys were in some kind of trouble, but it’s the kind of trouble that makes their viewer smile. In his portraits of women, MacLellan nearly always drew them in action and often gave his models a prop, such as this woman holding a golf club—as well as a divot showing she couldn’t quite do it right.

John E. Sheridan

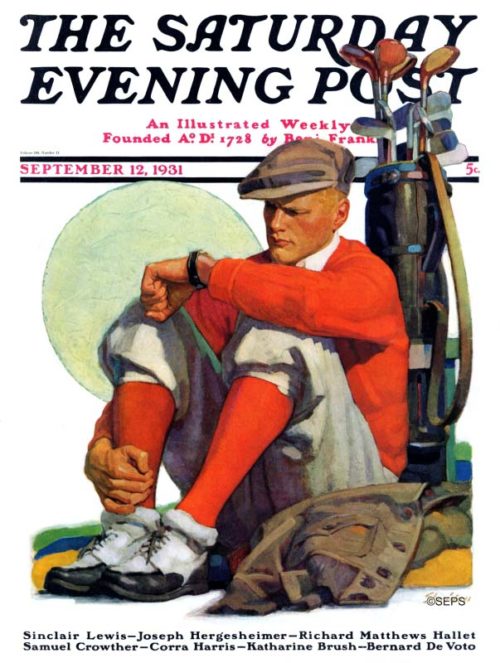

September 12, 1931

John E. Sheridan’s 14 covers for the Saturday Evening Post ran from 1918 to 1939. The covers are mostly sports related. The artist chose to focus on the greatness of American institutions such as baseball and the military, or in this cover’s case, golf. The artist’s style became less and less popular on the cover as other Post artists gained national recognition. Toward the end of his career, Sheridan accepted a teaching position in New York City at the Cartoonist’s and Illustrator’s School, also known as the School of Visual Arts. Today, his work is remembered as era-defining American sports and military.

Penrhyn Stanlaws

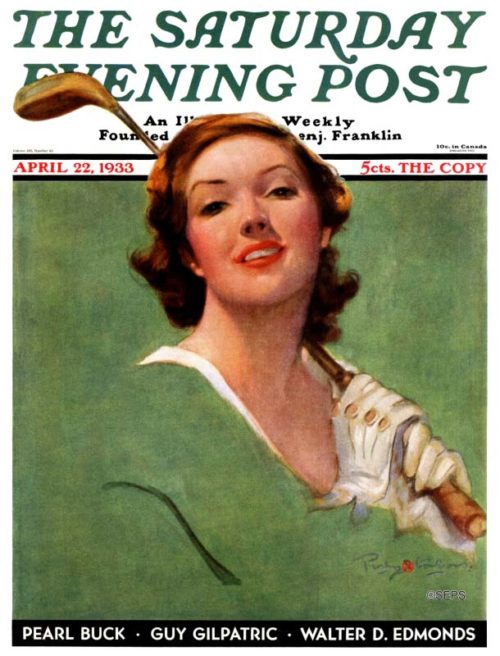

April 22, 1933

Penrhyn Stanlaws’ first cover with the Saturday Evening Post was in July 1913. He typically painted women dressed in their finery, and as color started making its way into many illustrations, Stanlaws usually added a singular element to punctuate the piece. The element, like this woman’s golf club, let the viewer explain the action on their own terms. His brush often added a soft illusion that gave a dreamy appeal to the characters he portrayed.

John Falter

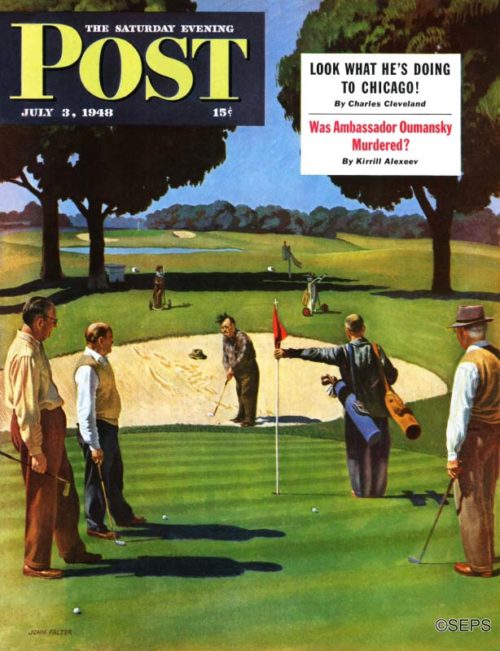

July 3, 1948

The men John Falter used as models for his golf painting will be surprised at what has happened to the course. The golfers were playing a course near Phoenix, Arizona. Falter added trees he thought would look more general. Falter thinks all the men he painted are giants of industry, and we would identify them but for the fact that Falter probably moved faces and figures around. The trouble with a picture like this is that it leaves everybody wondering if the sand-trapped gent got out. If an artist can take liberties with the scenery, then we can give you the ending. He laid that shot right into the cup, making the rest of them look like amateurs.

Constantin Alajalov

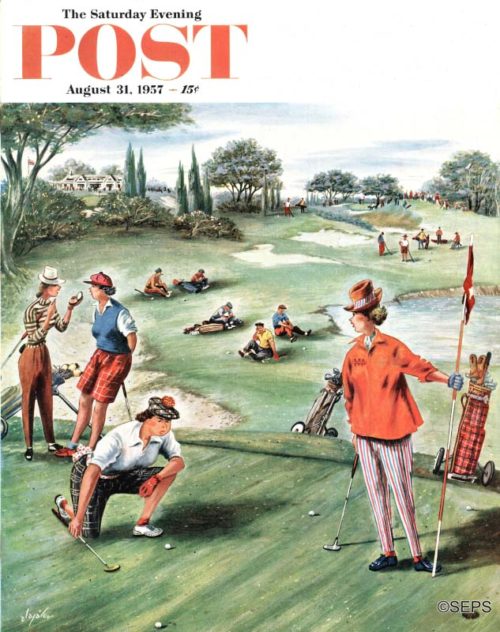

August 31, 1957

Men play golf too intensely; it is unhealthy to get all lathered up about how many swats it takes to get a ball in a hole. Linksmen should sit down occasionally and soothe their nerves by contemplating the loveliness of nature—the placid ponds, the golden sands, the enchanting wilderness beyond the fairways. Oh, let’s change the subject. Alajalov wants to say that while those ladies are slow-pokes all right, some men golfers are even slower pokes—in fact, some women poke the ball faster than most men. He also wants to say that he didn’t design those clothes; he sketched from life and saw the pantaloons two fairways away. Alajalov plays golf, but when asked about his score, he said to tell you that his voice faded away because of telephone-circuit trouble.

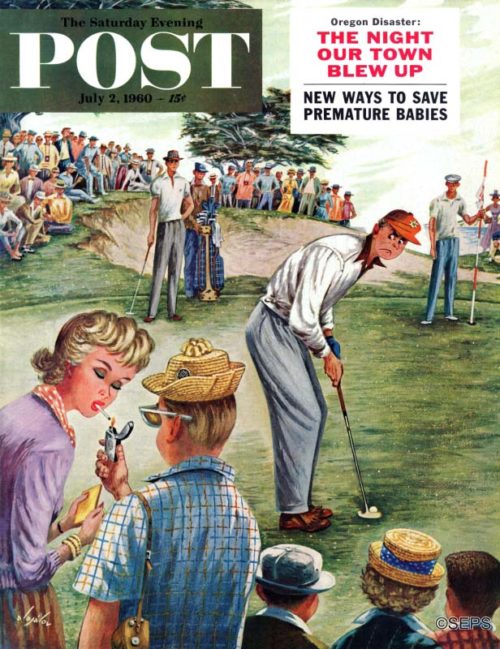

Constantin Alajalov

July 2, 1960

“Golfe” was outlawed during its infancy in Scotland because too many archers, on whom the defense of the land rested, were golfing when they should have been on the archery range. Today it’s possible to play golf and shoot arrows (or daggers, at least) simultaneously; witness the baleful glare of the sourpuss on our cover. Artist Constantin Alajalov, who shoots in the high 80’s, sympathizes with sourpussses whose games are sabotaged by Sunbonnet Sam and his ilk. Sam is the so-and-so in the foreground who is loudly striking up an acquaintance while our jittery’ golfer asks himself, Isn’t that the chowderhead whose noisy, blankety-blank camera shutter cost me a stroke on the last green? Which helps explain why certain golfers appear to have a stroke every time they drop a stroke.

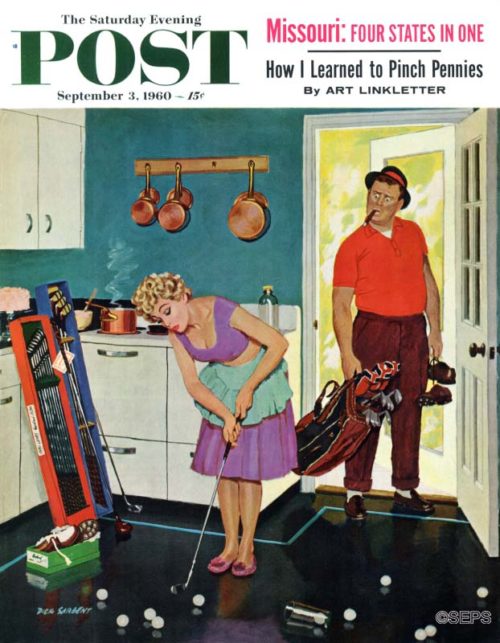

Richard Sargent

September 3, 1960

Question: “Is this the right way to hold the stick, dear?” Answer: “Oh, my achin’ back!” Male golfers have had to put up with this sort of thing ever since Mary, Queen of Scots, became addicted to the game more than four centuries ago. It’s unlikely, of course, that our cover lady will sink many long putts with the iron she’s holding. But there’s nothing wrong with her approach. (See cake at left, designed to repair her husband’s crestfallen expression and aching back.) Artist Dick Sargent informs us that we are in debt to his wife, Helen, whose example inspired this week’s cover. Mrs. Sargent splurged on a set of golf sticks a year ago and at last count had played a total of fifty holes. The total number of swings the lady took to play those holes is not a matter of public record.

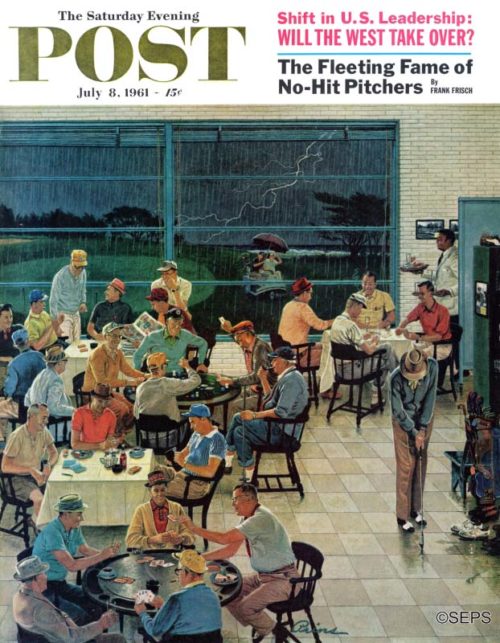

Ben Kimberly Prins

July 8, 1961

How do you like that? On Saturday afternoon-prime time at any golf club-comes the deluge. Well, that’s par for the course, we suppose, and the course in this Ben Prins cover belongs to The Dunes Club of Myrtle Beach, South Carolina. That wave in the background is a fringe of the Atlantic Ocean. not the crest of an oncoming flood. The three-wheeled vehicle under the umbrella is what is known as a caddy car, and its occupants are either fair-weather athletes scurrying toward the indoor recreation of the nineteenth hole, or spirited souls bent on challenging their fellow duffers to a game of motorized water polo. At any rate they’re not slowing down at the putting green. The weather being what it is, they’re probably less concerned about sinking putts than about sinking, period.

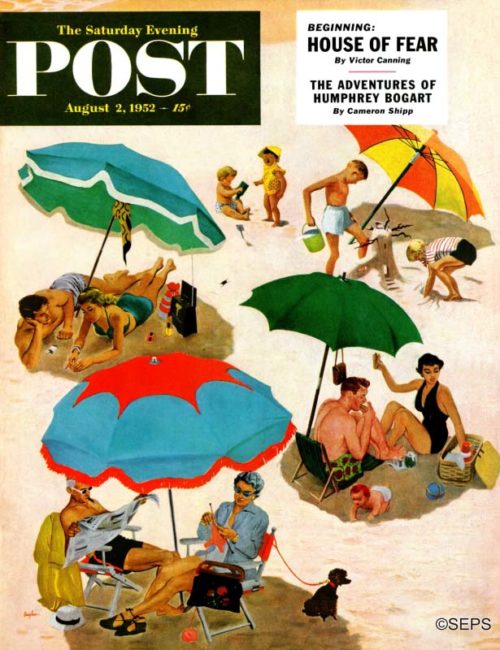

Cover Gallery: A Day at the Beach

These beachgoers on the covers of the Post are having the dream summer vacation.

Ellen Pyle

August 7, 1926

The Saturday Evening Post was the first magazine to accept Ellen Pyle’s work after her husband’s death in 1919. “The girl I am most interested in painting is the unaffected natural American type,” Pyle said in her 1928 interview with the Post. Her children often posed as models for Pyle’s paintings, but it was her brilliant use of color and loose, broad brushstroke style that made her one of the Post’s most recognizable female artists.

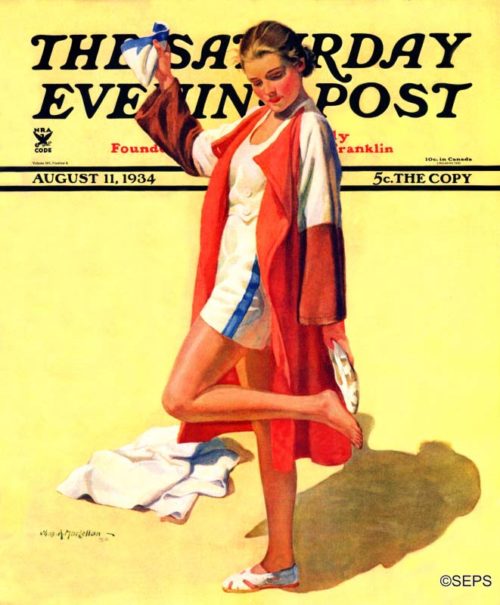

Charles A. MacLellan

August 11, 1934

Charles A. MacLellan started creating art for the Post during a time when narrative illustrations dominated the covers. His most memorable covers were those with children, typically boys. Often these boys were in some kind of trouble, but it’s the kind of trouble that makes their viewer smile. In his portraits of women, MacLellan nearly always drew them in action and often gave his models a prop, such as this woman and her beach clothes.

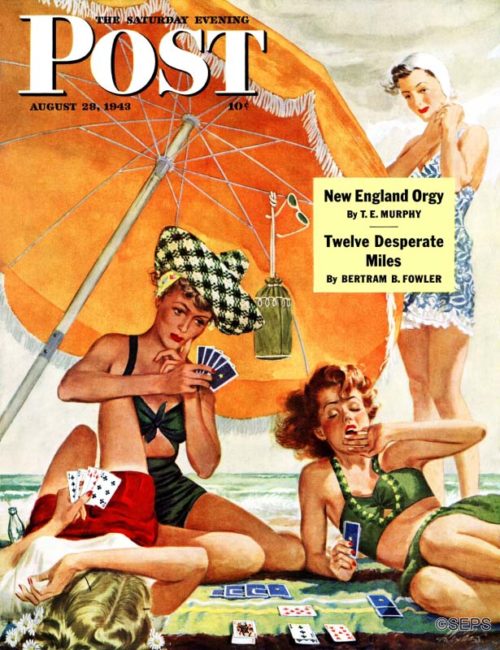

Alex Ross

August 28, 1943

This is one of six covers that Alex Ross painted for the Saturday Evening Post. All of his covers featured beautiful women, but this beach scene is the only one that doesn’t focus on a single girl. This 1943 cover does follow Ross’ usual style, however, because the women don’t appear to be over-joyed about their card game.

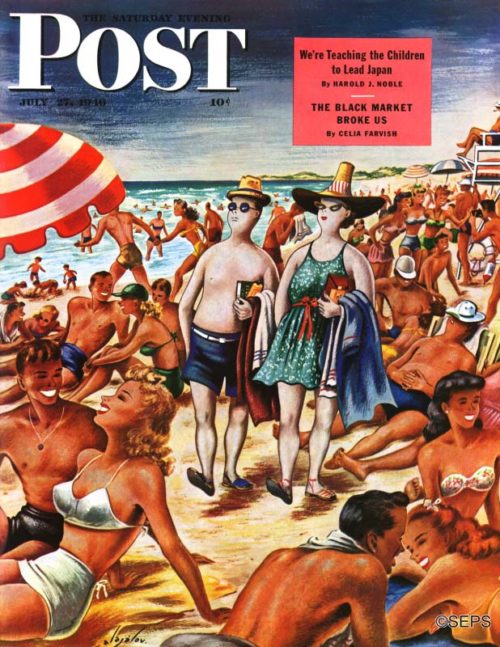

Constantin Alajalov

July 27, 1946

Constanin Alajalov’s painting of the new arrivals picking their green and embarrassed way through the tanned regulars, could have been made on any beach in the country. For that feeling of outstanding pallor is well known from coast to coast, and there is no lotion for it, except that in a few days you can sneer at even later arrivals. Alajalov made his sketches in Palm Beach, Florida, when the Northerners were arriving last winter.

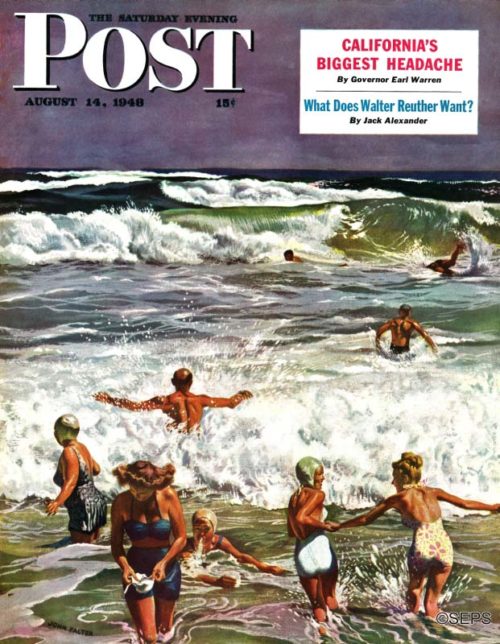

John Falter

August 14, 1948

Artist John Falter’s setting for his surf-bathing cover is Ogunquit, Maine. He made his first sketches while spending the summer in Maine, but didn’t get around to painting until last winter. By that time the lucky lad was in Phoenix, Arizona. The hotter that Arizona sun got, the more fondly the artist thought of Maine’s cool air and cool spray. So he went to work on a picture of Maine as remembered in the Southwest. The pretty girl in the left foreground, just emerging and shaking out her hair, often appears in Falter’s cover paintings. But doesn’t get a model’s pay for her work. She is Margaret Falter. John’s wife.

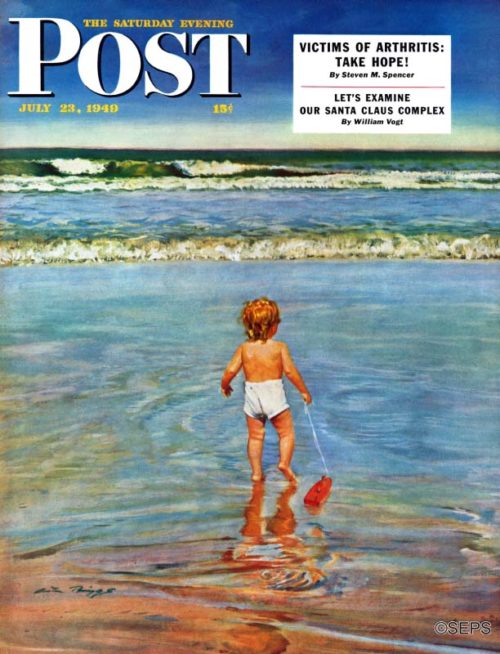

Austin Briggs

July 23, 1949

Don’t worry about the tiny cover girl who is going down to the awesome sea with her eight-inch ship. Just as Austin Briggs, who was vacationing at Folly Beach, Charleston, South Carolina, spied the seagoing tot, her mother let out a yelp and splashed into the foam after her. Now there, thought Briggs prophetically, could be my first Post cover.

George Hughes

August 2, 1952

In the winter, people buy sun lamps to get sun, and in the summer they buy beach umbrellas to keep the sun off. Well, have a wonderful time, folks; build your sand castles and your dream castles; let the cool winds and the hot dogs renew you; and don’t even let the annoyment creep in if that boy’s radio prevents your hearing the sweet nothings he whispers to his girl. Now turn the page, before the kids start throwing sand.

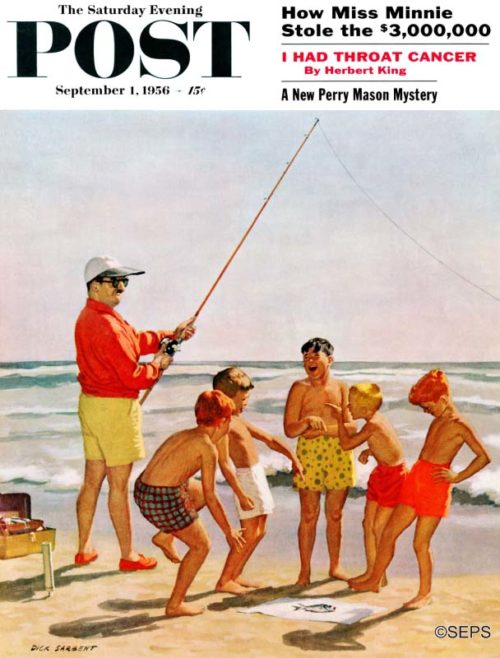

Richard Sargent

September 1, 1956

Mr. Rodney Fischer, an eminent metropolitan banker who is accustomed to being treated with deep respect, is not being. If that is a sardine he has caught, it may cop the surf-casting championship, for it is indeed of great size. But the boys’ happy faces and the man’s apoplectic face indicate that it is a small sample, or child, of something more ambitious. Mr. F. should set his rod in the gadget Dick Sargent has painted behind him, and lie down and relax his bile; if he goes to sleep, he may catch something decent. While he stands up, his blinding raiment must terrify all the fish who are old enough to think.

Cover Gallery: Salute to the 50 States

From the lighthouses of Maine to the majestic Cascades of Oregon, The Saturday Evening Post has represented every state on its cover. Here are 50 of our favorites.

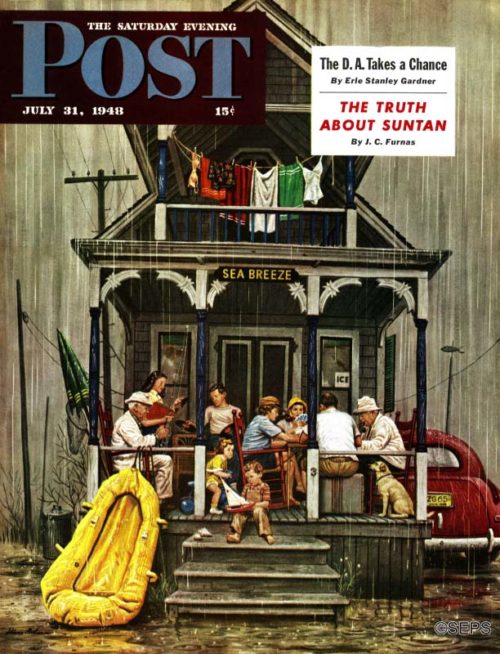

Rainy Day at the Beach

Stevan Dohanos

July 31, 1948

This lonely, wet house surrounded by raindrops and telephone poles would fit right in at Ft. Morgan Beach, Alabama, the narrowest strip of land with nothing but sand, sea grass, and a handful of houses.

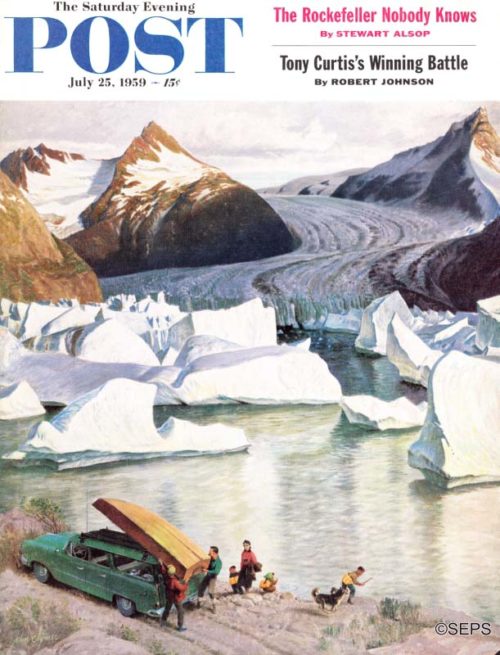

Portage Glacier

John Falter

July 25, 1959

One overheated July day when artist John Clymer was motoring in Alaska he paused at this spot at Portage Glacier. People came and boated around beside the small bergs. Next day, when John returned to sketch, a change of wind had blown Mother Nature’s chopped ice over against the glacier, and the sketching spot was as hot as Tophet. The artist says no, he did not go over and take a ride on the glacier.

Prospector

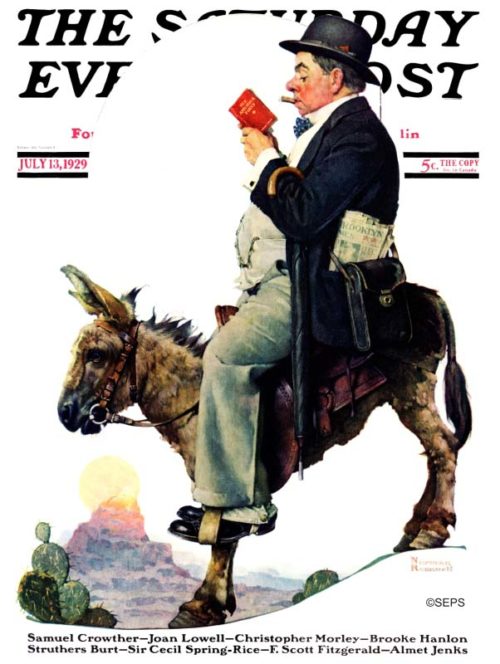

Norman Rockwell

July 13, 1929

Rockwell portrayed many forms of transportation in his Saturday Evening Post covers. People traveled by car, train, boat, airplane, soapbox, and stilts, but there was only one way to observe the mountainous terrain of the West successfully – on the back of a mule. When Rockwell traveled through the West, he preferred to tickle his audience with human-sized details, rather than its awesome magnificence.

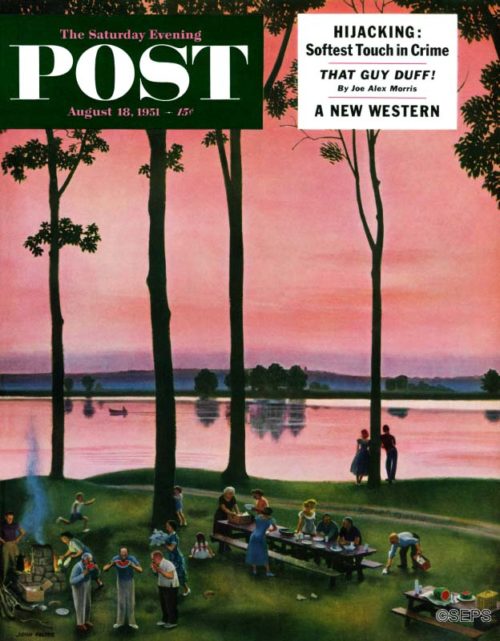

Evening Picnic

John Falter

August 18, 1951

Sometimes Nature rains on a picnic; sometimes she is just neutral; and sometimes, as in this mood caught by John Falter’s brush, she glories in the occasion herself, painting a magic sunset, smoothing the waterways into mirrors, tempering the temperature, even arranging for watermelons to be at their most luscious ripeness.

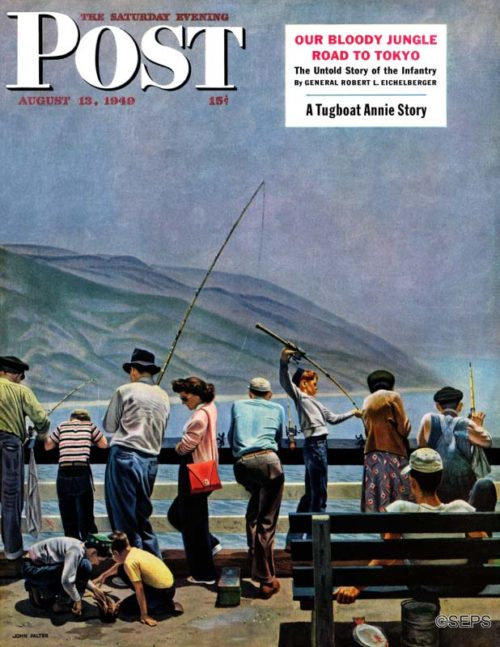

Santa Monica Pier Fishing

John Falter

August 13, 1949

On the long fishing pier at Santa Monica, California, tourists from all over the United States stand packed together like sardines while they try to catch fish. Many of the fishermen go through their routine calmly and expertly; occasionally a greenhorn flies into a tizzy, yelps for the landing net and hauls in a dwarf flounder or something else depressing. Artist John Falter was non-committal about whether he caught anything—besides a Post cover.

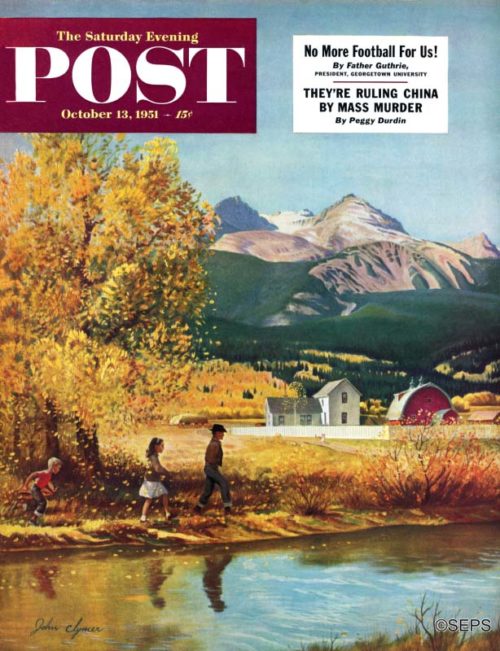

Colorado Creek

John Clymer

October 13, 1951

John Clymer, unable to put all of America on one canvas, settles for a mountain valley in Colorado, where pines and cottonwoods are waging a color battle in the foothills of the Rockies, while up beyond the timber line the slanting sun rays play a red-and-violet game of tag.

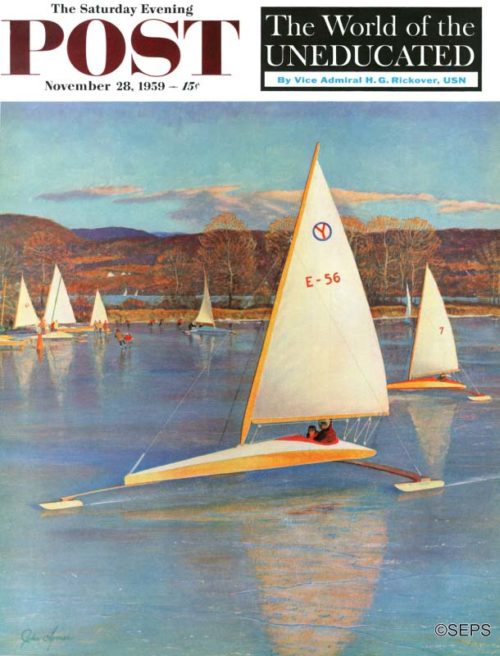

Sailboats

John Clymer

November 28, 1959

Hollanders started putting runners on boats circa 1750. Early United States ice- boaters appeared on the Hudson, where they raced New York Central trains. In 1959, ice-yacht clubs were likely to spring up wherever it didn’t snow too much but where water turned hard in winter. The original caption from 1959 claims this to be Lake Warren, Connecticut, but modern searching could find no such lake. Perhaps it’s Lake Waramaug, near the town of Warren.

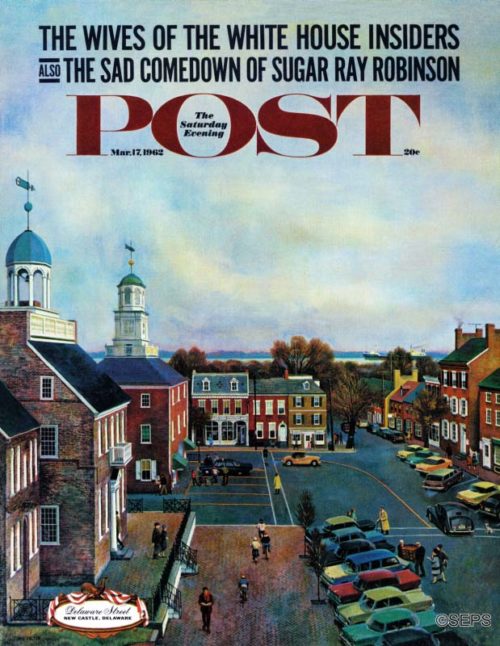

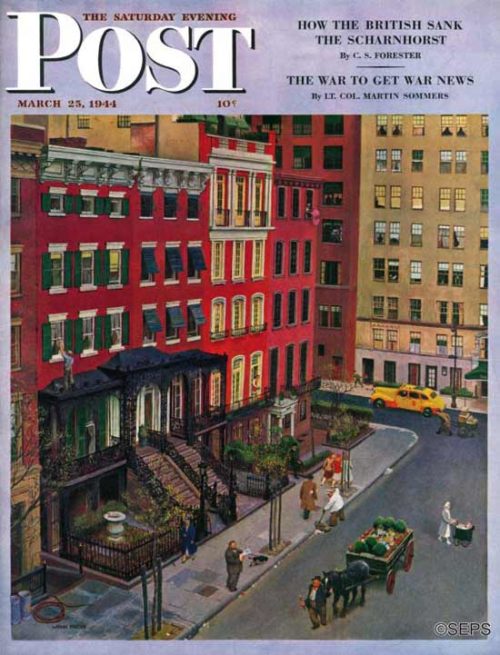

Town Square, New Castle, Delaware

March 17, 1962

New Castle, on the busy Delaware River, is six miles south of the state’s largest city, Wilmington, and two miles off the main highway. Once it was Delaware’s capital. Founded in 1651, it was William Penn’s landing place when he came to America in 1682. Penn is thought to have spent a night in the house at the extreme right of our cover. The spire atop the Court House (left foreground) was used as the center of a twelve-mile radius in part of the 1763-67 survey—to settle a boundary dispute—that resulted in the Mason-Dixon Line, which later played a key part in United States history.

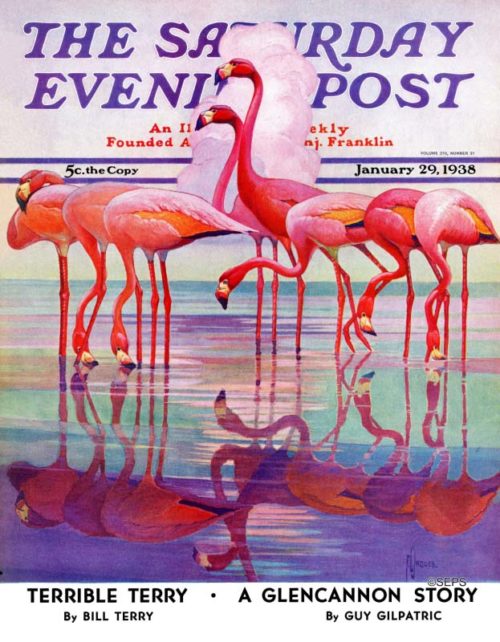

Pink Flamingos

Francis Lee Jacques

January 29, 1938

In the early 1800s, Florida was home to hundreds of thousands of Flamingos. By the turn of the century, the wild birds were all but gone from the state, eradicated by egg and feather collectors. In recent years, the birds seem to be making a slow comeback in the Everglades, a vast improvement over the plastic, front-lawn variety.

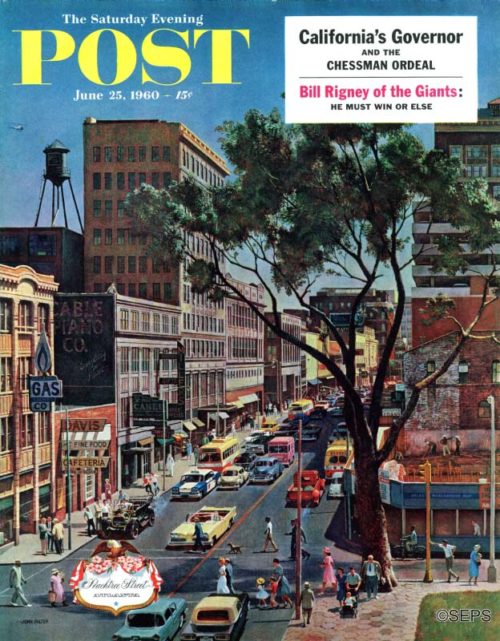

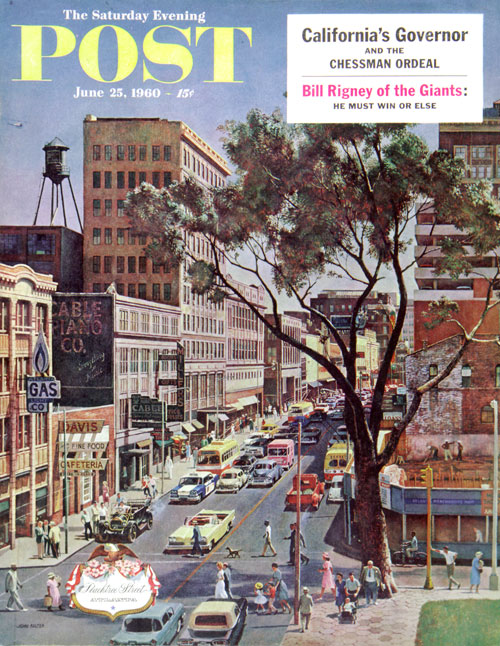

Peachtree Street, Atlanta

John Falter

June 25, 1960

John Falter depicted Peachtree Street at the Harris Street intersection, looking south toward Five Points. The gentleman on crutches at lower left is Ernest Rogers, who was an Atlanta Journal columnist and the popular “Mayor of Peachtree Street.”

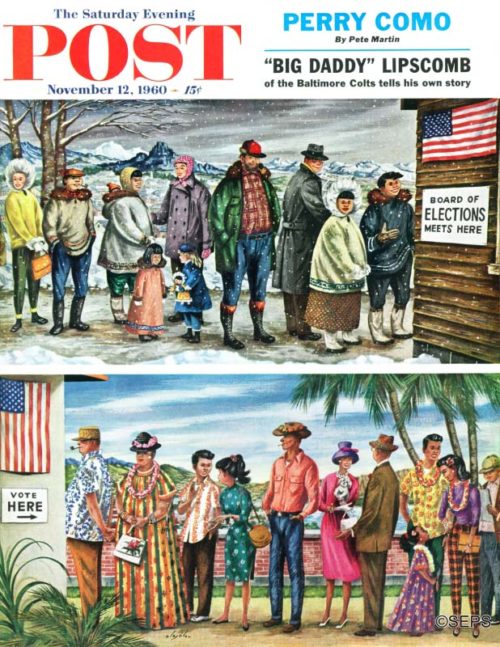

First Vote in the New States

Constantin Alajalov

November 12, 1960

We couldn’t find a cover dedicated solely to Hawaii; here it must share billing with Alaska, the other “new” state in 1960. Cover artist Constantin Alajalov shows the citizens of each state waiting in line to vote in the 1960 presidential election (Nixon v. Kennedy—Kennedy won). Alajalov earned his voting rights the hard way. He was born in Rostov, Russia, and arrived in New York in 1923. Naturalized citizen Alajalov has produced a lighthearted scene, but his underlying message gives us pause: This amalgam of people living together in harmony is bright evidence of the democratic way of life they’re voting to preserve.

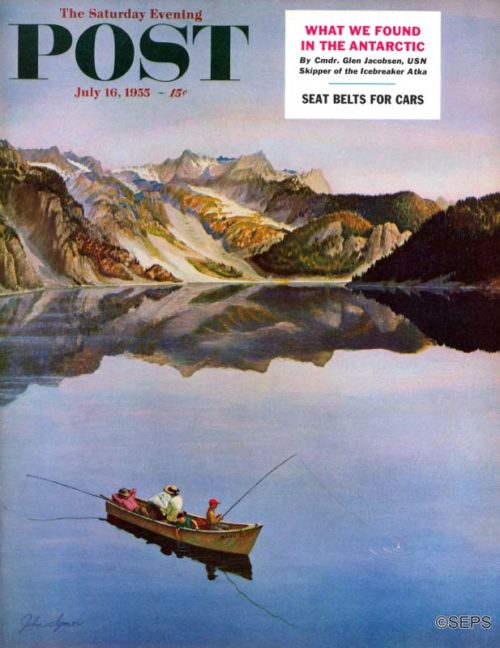

Fishing on a Mountain Lake

John Clymer

July 16, 1955

In America’s Western skylands are many jewel lakes, set in the gold and silver of clasping peaks. This looks to be in the vicinity of Sawtooth National Forest, but which mountain lake is anybody’s guess.

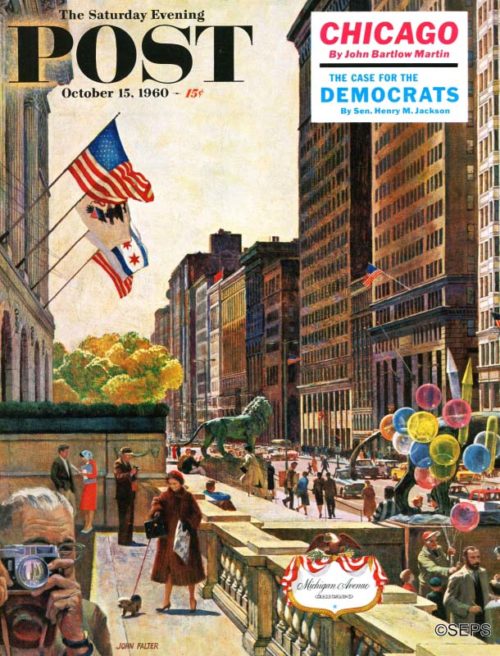

Michigan Avenue, Chicago

John Falter

October 15, 1960

The standard picture-post-card view of Chicago is of Michigan Avenue, looking north toward the Tribune Tower and Wrigley Building. Artist John Falter gives us instead a southern exposure of this elegant avenue—with the Wrigley Building and environs reflected in the camera lens at left. Behind the lofty buildings on the right is the Loop; facing them are the Art Institute, set in Grant Park, and Lake Michigan. The whiskered gent with sketch pad is the late Louis Sullivan, Frank Lloyd Wright’s mentor and an architect who helped reshape the face of this frisky city. (Sullivan had an office in Orchestra Hall, the second building from right.) We thought we had spotted another eminent Chicagoan, Al Capone, in the foreground. But Falter assures us we’re imagining things.

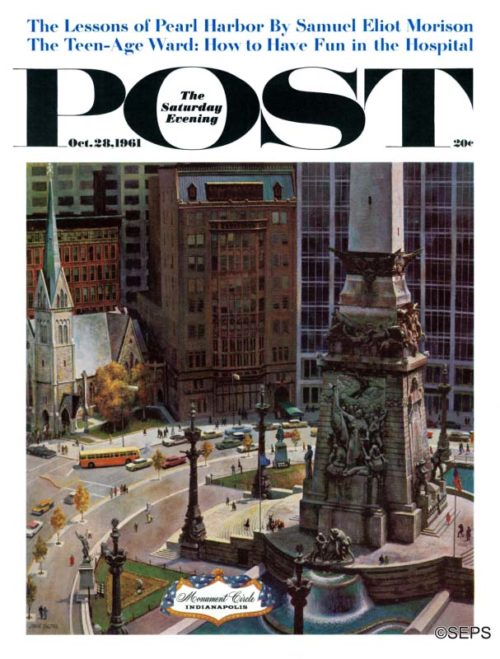

Monument Circle

John Falter

October 28, 1961

Monument Circle takes its name from the limestone memorial to soldiers and sailors at its center. And the circle is at the very center of Indianapolis, which is right in the middle of the Hoosier state. Artist John Falter discerned a faintly French flavor in this scene — perhaps because Indianapolis was planned on the pattern of Washington, D.C., which was laid out by a Frenchman. But consider the English Gothic architecture of Christ Church Cathedral at the left, the vaguely Tudor air of the neighboring Columbia Club, and the bluntly modern design of the Fidelity Building. French, English, or just plain American, the circle suits a city with a half-Greek name.

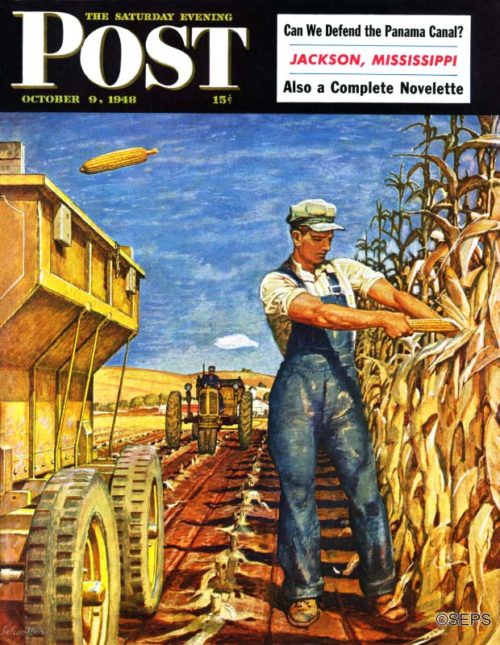

Corn Harvest

Mead Schaeffer

October 9, 1948

This Mead Schaeffer cover shows corn being picked by the “bang-board” method, which allowed a man to throw ears into the wagon without looking, because they would bang against a high board at the far side of the wagon and drop in. By 1948, most big farms used mechanical corn pickers, including the Lawton, Iowa, farm of Louis Peterson, the setting of this picture. The mechanical picker had already been used on much of the field, as the rows of stubble indicate, but the day Schaeffer was there, the machine was busy elsewhere. Farmer Peterson needed a little corn for his hogs. He got it the bang-board way—and Schaeffer got this cover.

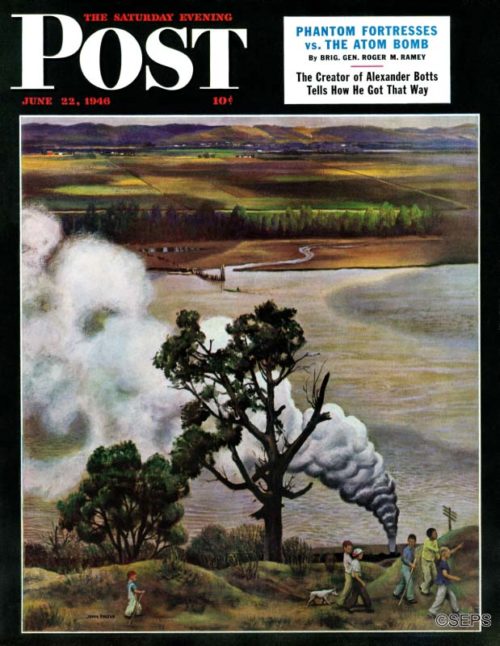

Steam Engine Along the Missouri

John Falter

June 22, 1946

You are looking across one of the great rivers of America—the Missouri. You are in Kansas, gazing across into Missouri. The town in the distance is Armour Junction. Those flat fields across the way are likely to disappear when the Missouri gets one of its expansive moods. John Falter painted the scene when he visited a farm his father had just bought—painted it, in fact, from a bedroom window in the farmhouse. He had paints and brushes, but no canvas, so painted this one over an old picture that came with the house. The tagalong lad bringing up the rear of the little expedition—Lewis and Clark used the same route—is Falter’s nephew.

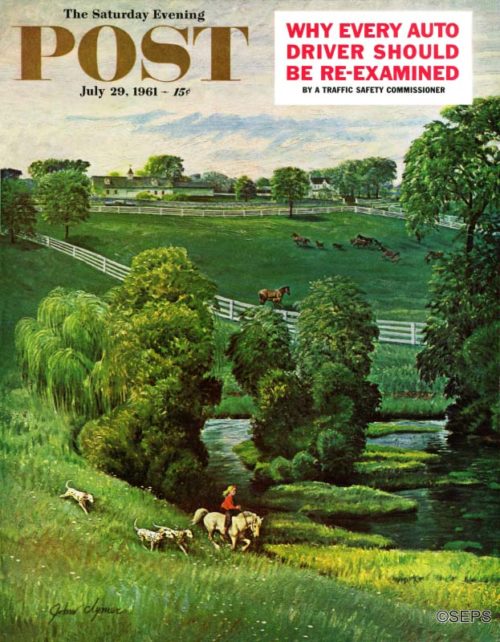

Green Kentucky Pastures

John Clymer

July 29, 1961

Our cover is a composite of scenes observed by artist John Clymer near Lexington. There may be gold—a future Derby winner, that is—among the foals behind the fences of that paddock. But none of the foals seems in a hurry to be over the fence and romping with Goldilocks and her three Dalmatians or thundering down the homestretch at Churchill Downs. Perhaps the reason is that the grass down here doesn’t always seem greener on the other side. This is Bluegrass country.

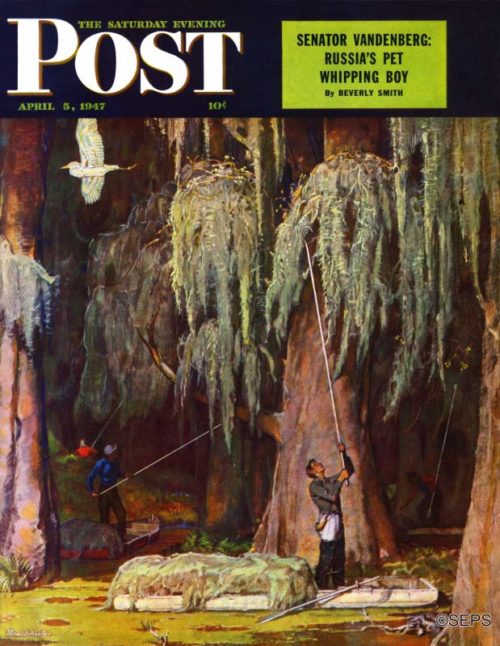

Spanish Moss Pickers

Mead Schaeffer

April 5, 1947

Artist Mead Schaeffer contributes another to our series of regional covers with a scene he sketched south of New Orleans, in the bayou country. Near Lafitte, Louisiana, he watched a harvest distinctive to the South. Moss pickers were hauling down boatloads of the beautiful Spanish moss that festoons trees in the South; the moss was dried and used in upholstering.

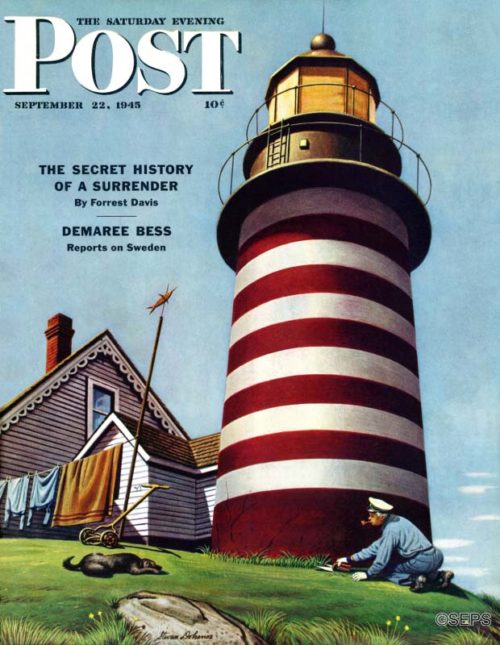

Lighthouse Keeper

Stevan Dohanos

September 22, 1945

The lighthouse on the cover is the West Quoddy Light, Lubec, Maine, but the lighthouse keeper is pruning the grass at Sankaty Light, Nantucket, a neat trick that can happen only in the world of art. What happened was that artist Stevan Dohanos made his preliminary sketches of the West Quoddy Light the summer before. The next year, to freshen his memory on lighthouse detail, he journeyed up to the Sankaty Light. It turned out the Sankaty Light had “a very strong personality of its own,” and wasn’t much good as a source of information on the situation in West Quoddy. However, they were cutting the grass at Sankaty Light, and Dohanos liked that touch of domesticity, so he included it.

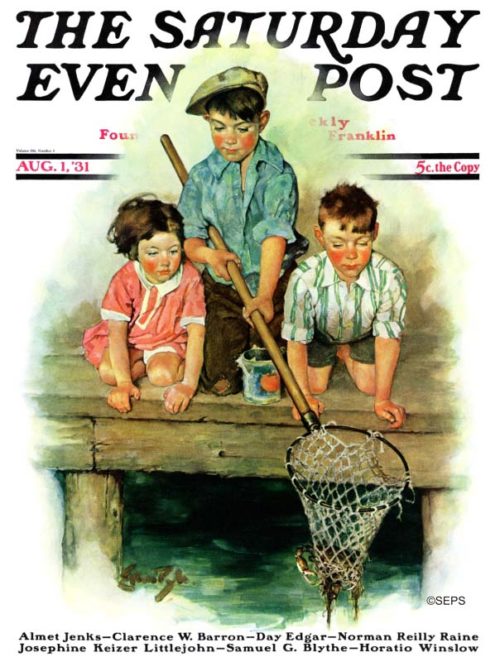

Crabbing

Ellen Pyle

August 1, 1931

The Chesapeake Bay makes a great location for crabbing, with more than 7,000 miles of shoreline and plenty of piers to dip your net. Any good Marylander knows what to do with that fat crab, but these kids don’t look so sure.

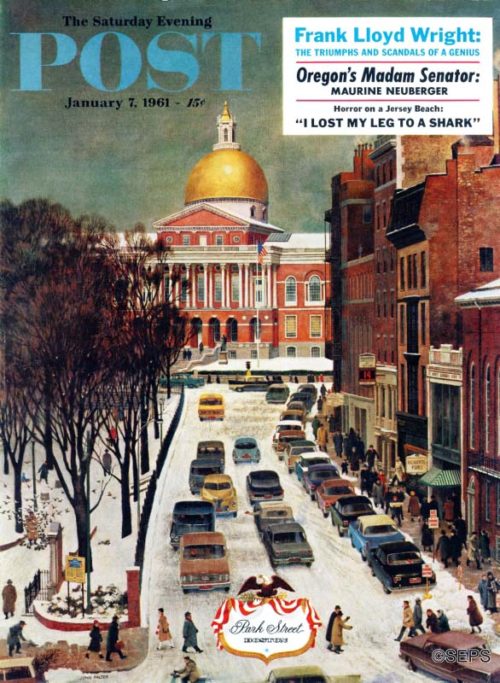

Park Street, Boston

January 7, 1961

Welcome to historic Park Street circa 1961, looking north toward the gold-domed State House. To the left, Boston Common; to the right, the Old Granary Burial Ground, where lie Paul Revere, John Hancock and Samuel Adams. That’s Park Street Church in the foreground; its site is known as “Brimstone Corner.” The yule tree being carted off at lower left indicates that Christmas no longer is banned in Boston, as it was when the Puritans held sway. As for the 1913 Pierce Arrow approaching from the right, artist John Falter tells us it originally belonged to Boston astronomer Percival Lowell, brother of poet Amy Lowell.

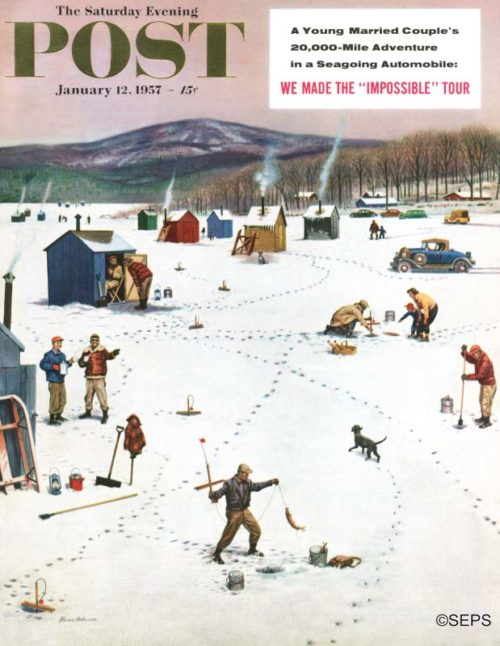

Ice Fishing Camp

Stevan Dohanos

January 12, 1957

These shacks, which sit over fishing holes on the ice, are as cozy as living rooms, though less roomy, and they smell deliciously of coffee with occasional whiffs of kerosene.

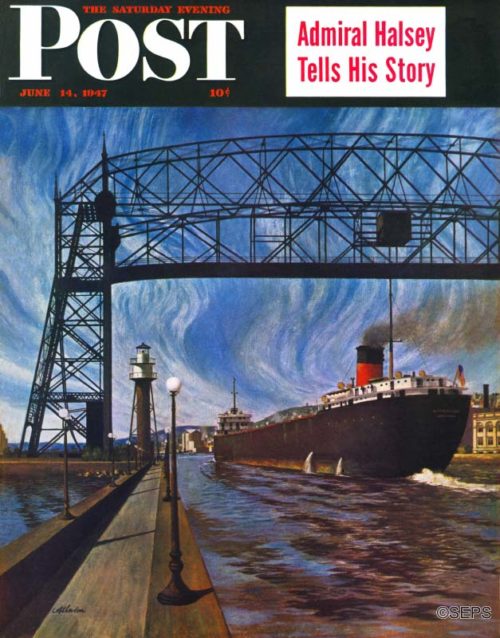

Ore Barge

John Atherton

June 14, 1947

John Atherton’s cover painting is a view of the husky city of Duluth. This is the ship canal through which ore boats moved out to begin their travels in the Great Lakes. The ore came from the great Mesabi Range. Atherton chose a moment when the bridge had lifted to let one of the ore boats pass below.

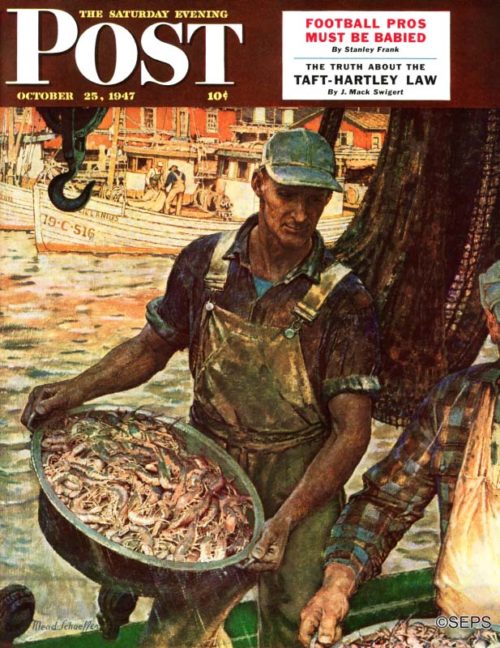

Shrimpers

Mead Schaeffer

October 25, 1947

Mead Schaeffer turned south to Biloxi and its shrimp-fishing fleet. As one who sees shrimp most often in a cocktail, served pretty sparingly, the artist was slightly staggered by the size of the fleet and the volume in which they bring shrimp to the packing houses.

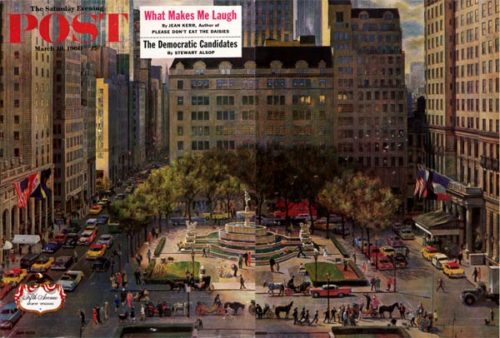

Kansas City

John Falter

September 23, 1961

Spanish architecture in Missouri? If such a state of affairs seems peculiar, consider that the unpredictable Show Me state even has a town named Peculiar (pop. 458), some twenty miles south of here, on U.S. 71. Our cover scene is in Kansas City, “the gateway to the Southwest,” and you are looking at the intersection where U.S. 50, gateway to the Country Club Plaza shopping center, crosses J. C. Nichols Parkway. This elegant community of shops was conceived and built by Jesse Clyde Nichols (1880-1950), to whom the fountain in the foreground is a memorial. The scene appealed to artist John Falter because the Old World architecture seemed to symbolize our nation’s roots — which is not to deny the notion expressed by lyricist Oscar Hammerstein in Oklahoma! that “everything’s up-to-date in Kansas City.”

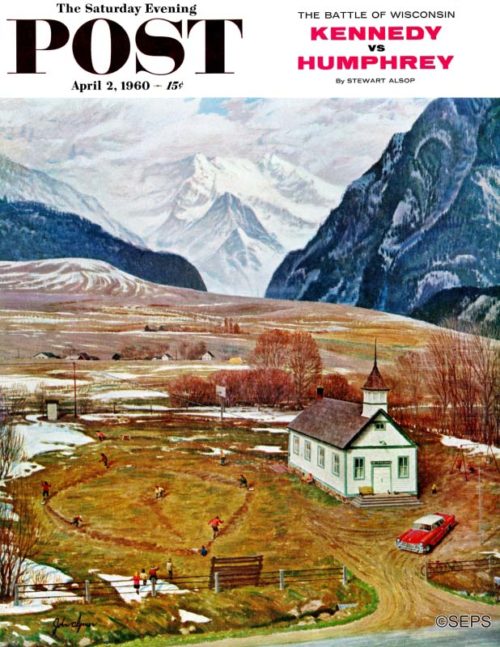

Recess at Pine Creek

John Clymer

April 2, 1960

It’s recess time in Pine Creek, Montana. Artist John Clymer had often passed this one-room schoolhouse en route to nearby Yellowstone National Park, thinking each time that it belonged on the cover of the Post. Clymer confesses that in order to get the part of the Absaroka Mountains on the canvas, he had to turn the schoolyard around.

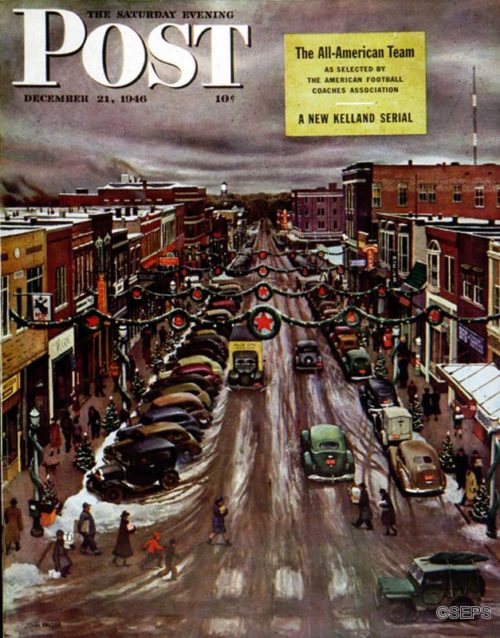

Falls City, Nebraska

John Falter

December 21, 1946

As a setting for his picture of the last-minute Christmas rush, John Falter chose the town where he spent his boyhood: Falls City, Nebraska. The finished job is a mixture of paint and recollection. That water tower in the distance, for example, was a favored roost for Falls City boys on hot summer nights. They liked to sleep there. City authorities met in some alarm — the surrounding platform is seventy-five feet above ground — and forbade it. Falter had no trouble recalling the Christmas rush. As a boy, he worked in his father’s clothing store on this street. A good many customers bought new outfits for the holidays, and young Falter was the pants runner — he ran trousers from the store to the tailor’s, to get them shortened. Only customers appear in this painting. But the artist’s sympathies doubtless are with those on the selling side of the counter.

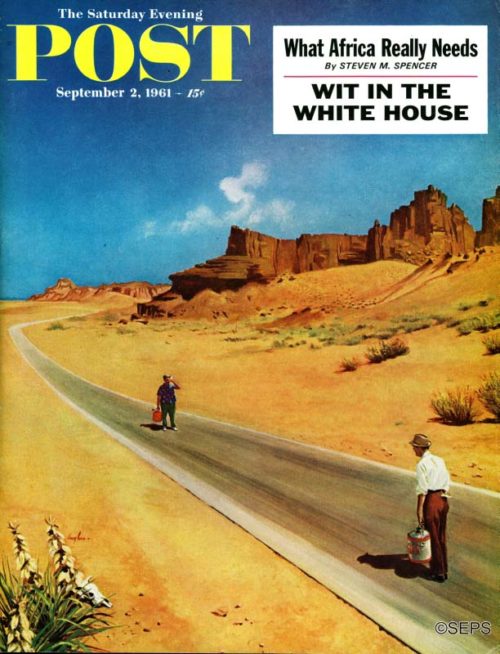

Out of Gas

George Hughes

September 2, 1961

The setting of this depressing encounter is not fifty miles from nowhere. This is nowhere. Artist George Hughes pieced together the landscape from some of the more desolate terrain of the Southwest, where the skies are not cloudy all day and where seldom is heard a discouraging word. Both pedestrians on our cover have, however, been subjected to some rather discouraging words: Exactly 2.6 miles in either direction is a fuelless automobile, and in each automobile sits a wife who was ignored earlier in the day when she suggested, “Don’t you think we’d better stop? The sign at that station says, Last Gas for 40 Miles.” And you should have heard the discouraging mutterings when these chastised males discovered that their spare-gas cans were drier than a sun-baked skull.

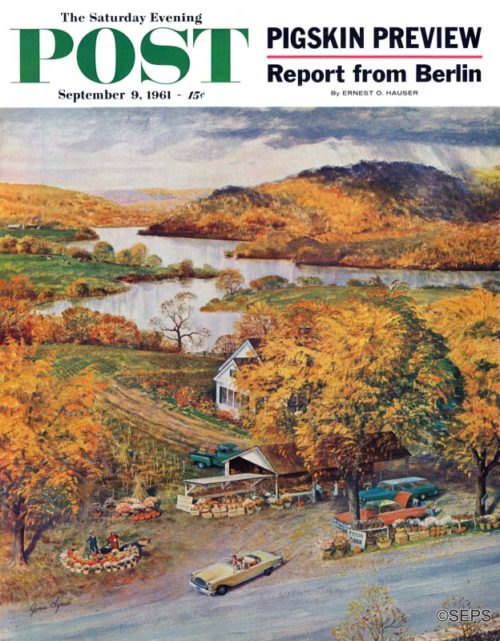

Roadside Vegetable Stand

John Clymer

September 9, 1961

What is more inspiring than the New England countryside in the fall? Indeed, the autumnal delicacies on sale in the foreground of John Clymer’s pumpkin-colored scene inspired us to turn to our bookshelf, where we found Henry David Thoreau saying, “I would rather sit on a pumpkin, and have it all to myself, than to be crowded on a velvet cushion.” (Although there’s no denying that pumpkins are more advantageously used in pies, soups and puddings.)

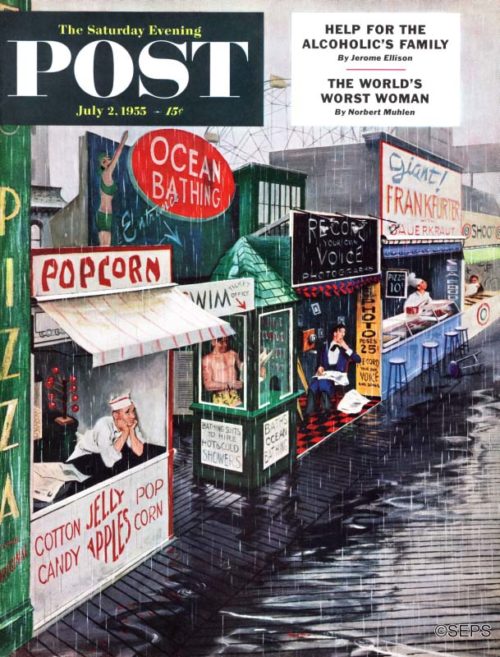

Rain on the Boardwalk

George Hughes

July 2, 1955

True, these poor fellows on Mr. Hughes’ boardwalk are heart-rending, also 5,000 souls sardined into nearby cottages, but as oceans are useless without water, can’t everybody resolve to observe this as Be Kind to Rain Week?

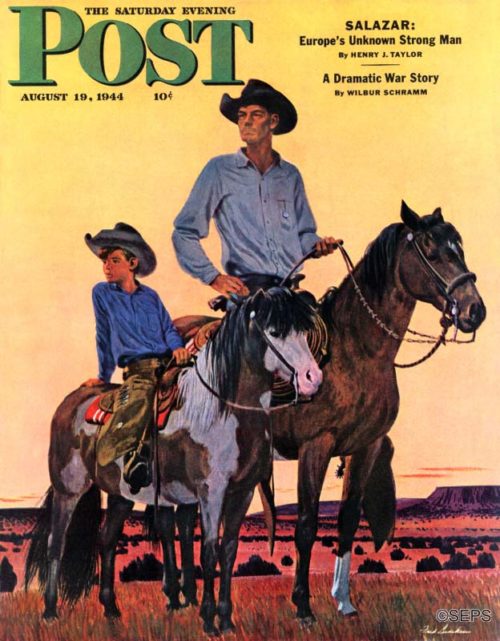

Surveying the Ranch

Fred Ludekens

August 19, 1944

Although Fred Ludekens lived most of his life in California, this scene has a distinctly New Mexican flavor. Ludekens never worked from photos and didn’t use models. Not one to limit himself to just one subject, Ludekens also painted interior images to accompany a Robert Heinlein story about interplanetary travel, which also appeared in the Post.

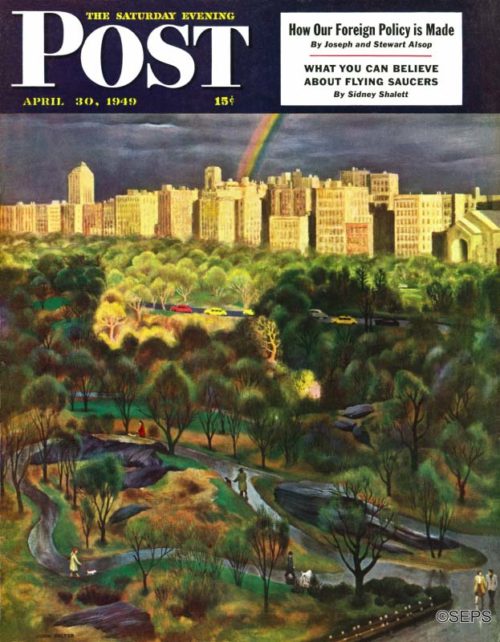

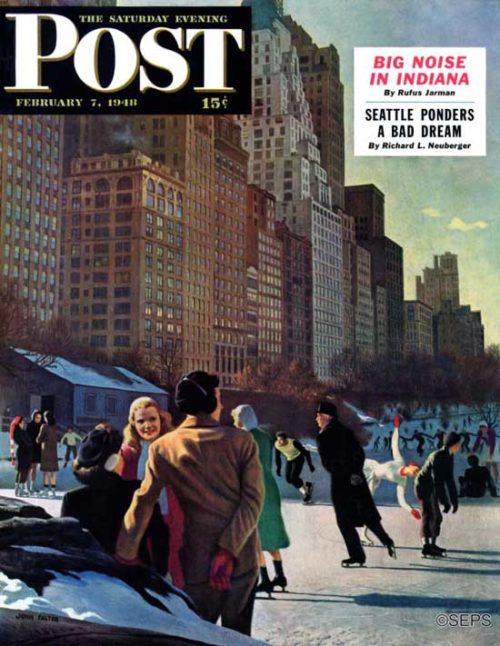

Central Park Rainbow

John Falter

April 30, 1949

When John Falter’s cover painting was accepted, there was lightning trickling down the sky beside the rainbow. Presently the Art Department began to worry—do lightning and rainbows ever show up at the same time? The ever helpful Weather Bureau was asked to look at the Post‘s storm—which has just doused midtown New York and is rumbling away beyond Central Park’s man-made ramparts. “Fair and cooler,” was the comment. “But we never saw a streak of lightning in such bright daylight. Of course, where weather is concerned, anything can happen.” So the picture was delightninged, leaving only that sign of clearing weather, a patch of blue sky large enough to make a sailor a pair of breeches.

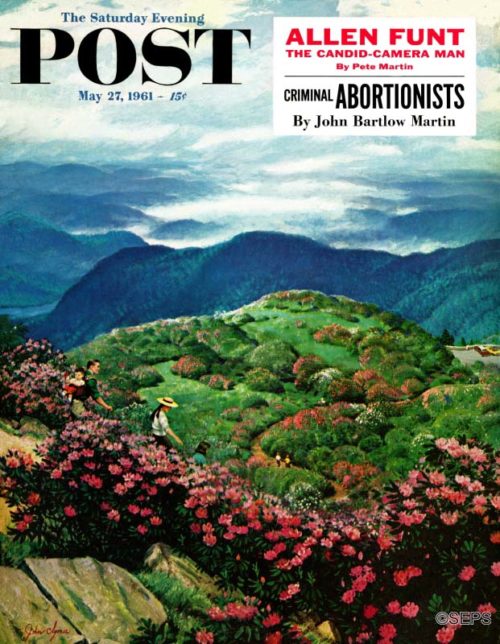

Appalachian Rhododendrons

John Clymer

May 27, 1961

Catawba rhododendron thrives in many sections of the southern Appalachians, but rarely is it so brilliantly beautiful as here at Craggy Gardens, along the Blue Ridge Parkway near Asheville, North Carolina. Our scene shows the trail to Craggy Pinnacle. “Sections of the trail wind through ten-foot-high rhododendrons,” artist John Clymer said. “And the ground is carpeted with the rich-pink petals of the flowers that have fallen.” Clymer’s painting is a preview of a coming attraction: These floriferous slopes look their best in mid-June, as they did in the days when the Catawba and the Cherokee held sway in the Carolinas.

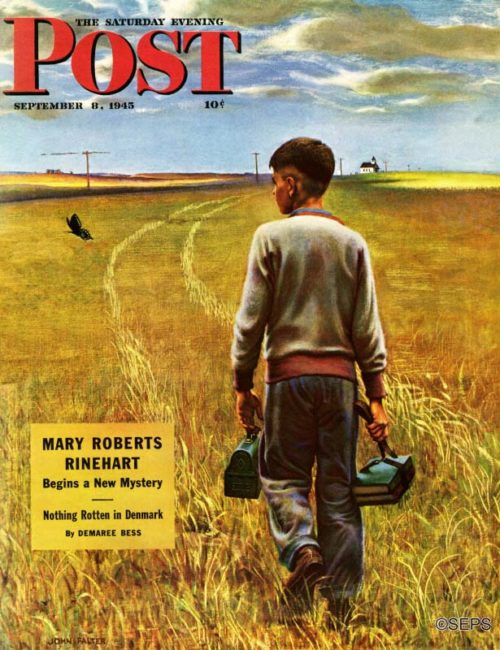

Amber Waves of Grain

John Falter

September 8, 1945

John Falter’s ” back-to-school ” cover shows a lad with a new haircut crossing the fields to a country schoolhouse. This is one that we’re not 100% sure is in North Dakota, but the scene landscape looks decidedly North Dakotan. If you’re from the state, let us know if you disagree.

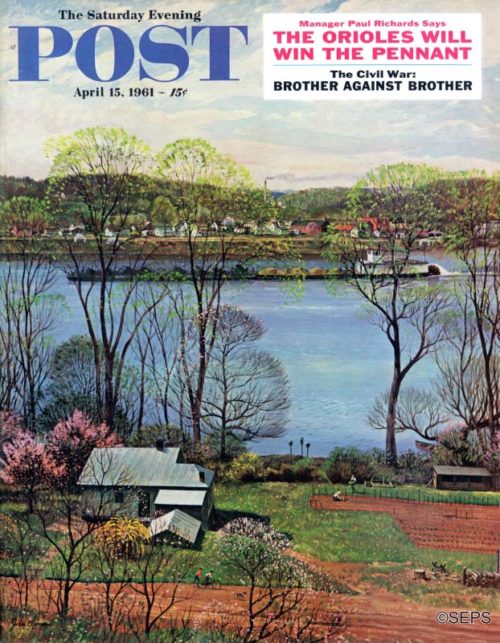

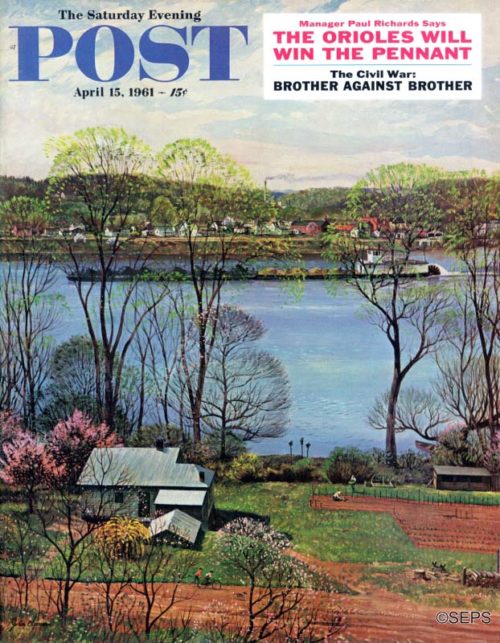

Ohio River in April

John Clymer

April 15, 1961

Heading down the Ohio is a venerable stern-wheeler, push-towing barges loaded with coal and gravel. Cargo by the tens of millions of tons is shipped up and down the Ohio in this manner each year, between Pittsburgh, at the confluence of the Allegheny and Monongahela, and Cairo, Illinois, where the Ohio empties into the Mississippi. (The watershed of the Ohio reaches into fourteen states.) Artist John Clymer formed his riverscape by piecing together the water’s-edge scenes that appealed to him most. The near shore is West Virginia; the far shore is Ohio.

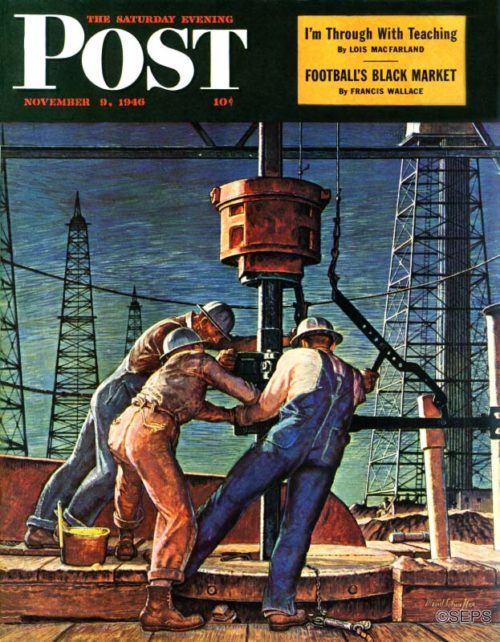

Drilling for Oil

Mead Schaeffer

November 9, 1946

Artist Mead Schaeffer and his wife worked near Oklahoma City, Oklahoma, for Schaeffer’s oil country cover—if you can call it ” working.” Had they come to town on a vacation, they couldn’t have had more of a social whirl. Their plane arrived just before sunrise and, much to the Schaeffers’ surprise, the fire chief’s red car was waiting. So was the mayor, who read a proclamation declaring them welcome and offered a key to the city. The Schaeffers found every minute they could spare had been booked for social engagements, and this was true throughout their stay. It was by all odds the warmest reception the Schaeffers have met in their travels working on Post covers, and they went away as impressed with Oklahoma courtesy as with Oklahoma oil.

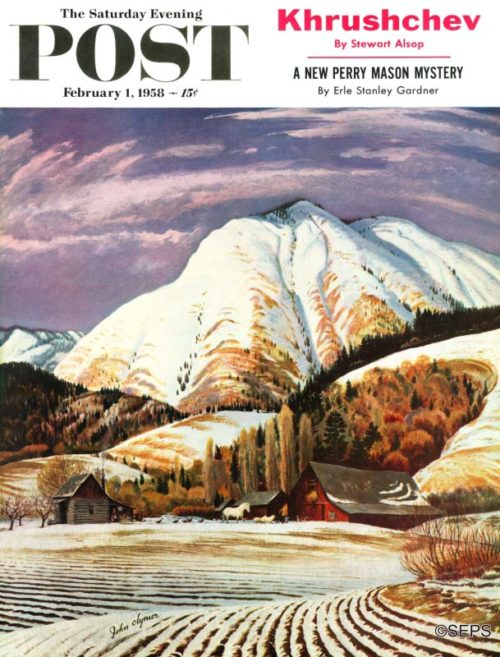

Cascade Mountain Farm

John Clymer

February 1, 1958

At length there’ll come a south-breeze day when the snow on the big hills will give Mr. Frost the heave-ho and begin rollicking down from the skylands in rejoicing cascades. That last word fits in here fine, come to think of it, for John Clymer’s scene is in the Cascade Range.

Independence Hall, Philadelphia

Allen Saalburg

June 2, 1945

In 1945, Independence Hall was just across the way from the Post. Allen Saalburg’s painting is a view of Independence Hall looking west. The building at the left was The American Philosophical Society. The Post‘s offices were directly behind the trees in the left foreground.

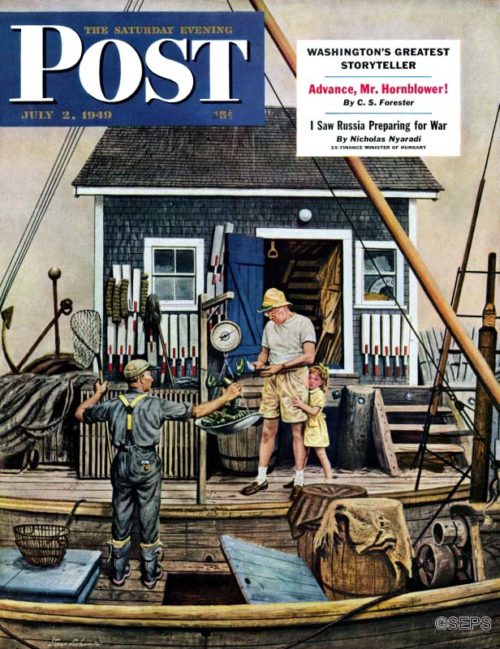

Buying Lobsters

Stevan Dohanos

July 2, 1949

The vacationer in the picture has been caught with that combination of mouth-watering smile and grimace of pain common to human beings when about to pay for a lobster. As for the little girl, you may be too old to recall that the first sight of a lobster is enough to scare the daylights out of anybody. After the first taste, fear vanishes.

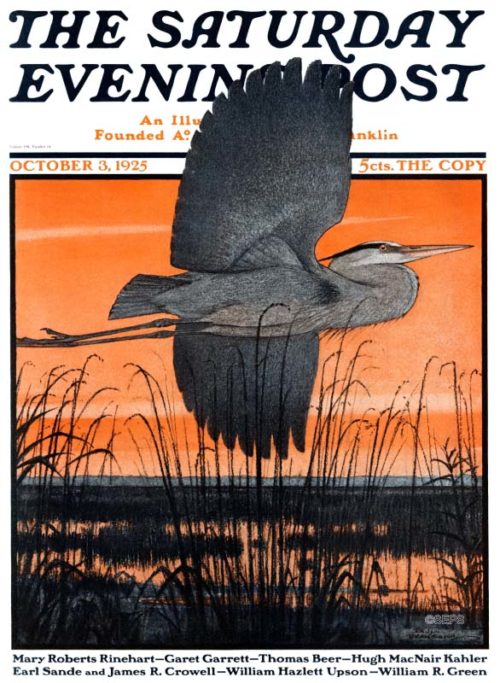

Marsh Bird

Paul Bransom

October 3, 1925

South Carolina has 344,500 acres of salt marsh, the most of any state on the east coast. This regal bird looks as though he’s happy to claim every last one as his own.

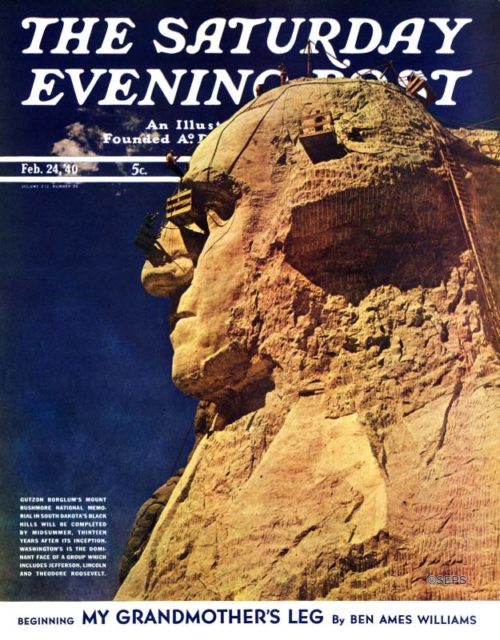

Mt. Rushmore

Lincoln Borglum

February 24, 1940

A photograph instead of an illustration was quite the departure for the Post at the time, but there was important information to document: Mt. Rushmore was scheduled to be completed later that year, so they took the opportunity to capture the monument during its final phase of creation.

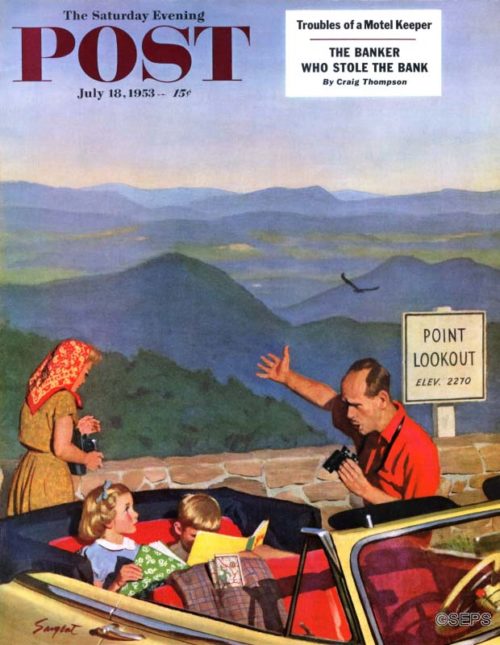

Point Lookout

Richard Sargent

July 18, 1953

Papa has been steering the bus for three days toward Point Lookout, and, having finally made it, is he not justified in decrying the little ones’ disinterest in lookouting? On the other hand, for three days the kids have been peering at interminable scenery; so now that the car has quit jiggling and reading is possible, what is more dutiful than rejoicing in the new hooks that papa bought them to read? Of course, modern readers may long for the days when children were glued to books and not phones.

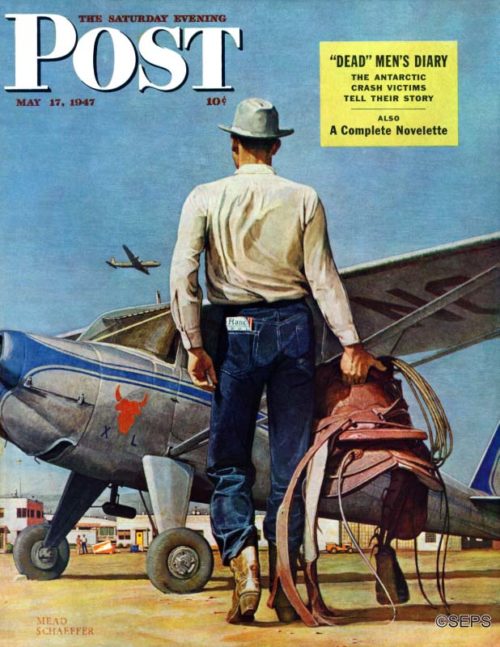

Flying Cowboy/ Airport at Amarillo, TX

Mead Schaeffer

May 17, 1947

“The cowboy carrying his pet saddle to his plane is an everyday sight in the West,” artist Mead Schaeffer wrote when he delivered this painting. “Many a rancher lives in town and commutes to his ranch or ranches by air. The tableland makes landing fields all through the West, and because of the long distances involved, the West takes to planes the way the East takes to cars. Many a business engagement, even luncheon engagements, are kept this way.” One of the flying ranchers, Lee Bivins, was Schaeffer’s model. The background is the airport at Amarillo, Texas.

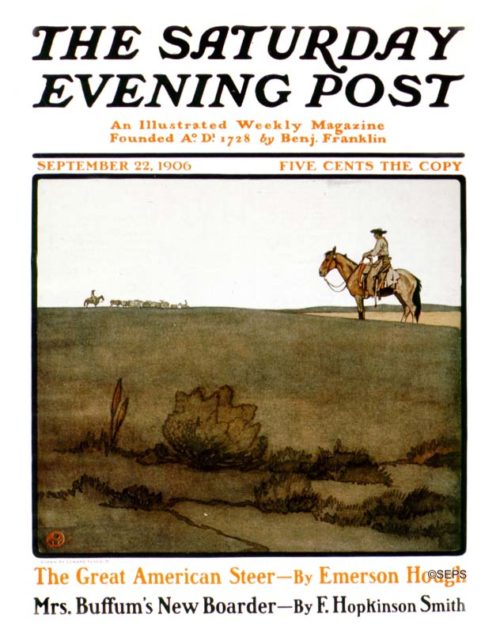

Cowboy

Edward Penfield

September 22, 1906

Artist Edward Penfield is considered the father of the American poster and was an important figure in the field of graphic design. You can see Penfield’s development of the use of simple shapes and limited colors in this work. Are we sure this is Utah? No, but we can’t be too far off the mark.

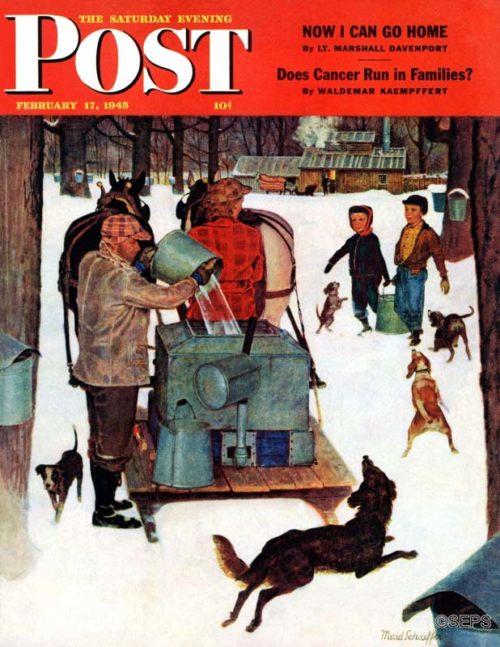

Maple Syrup Time in Vermont

Mead Schaeffer

February 17, 1945

The models are Arlington, Vermont, neighbors of artist Mead Schaeffer’s, Mr. and Mrs. Jim Edgerton and their children. The Edgertons owned one of the best sugar bushes—a bush is a grove of sugar trees—in that section. The shed in the background is the boiling-off house. Vermont farmers can, and do, argue for hours and days over what is the best time to tap. The season starts as early as February and may end as late as April.

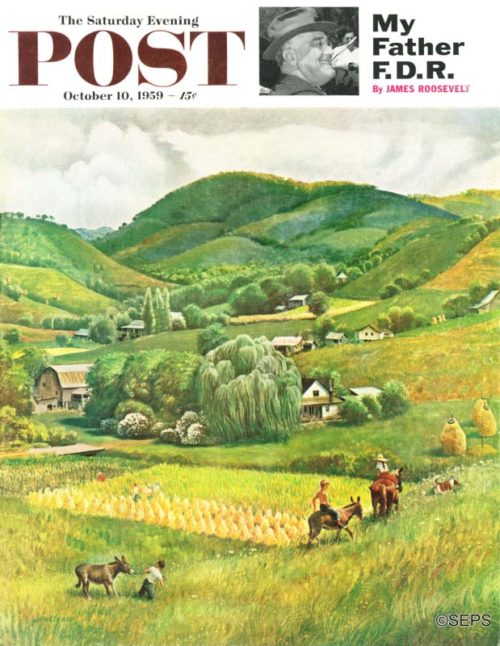

Blue Ridge Burro Ride

John Clymer

October 10, 1959

When those green highlands are seen from afar, they are blue, as highlands are wont to be. Hence, long ago somebody had an inspiration and named them the Blue Ridge Mountains. In the foreground you see a stationary burro, a detail which painter John Clymer probably considers a still life. It’s a pretty fair bet that fifteen minutes from now the animal will still be still.

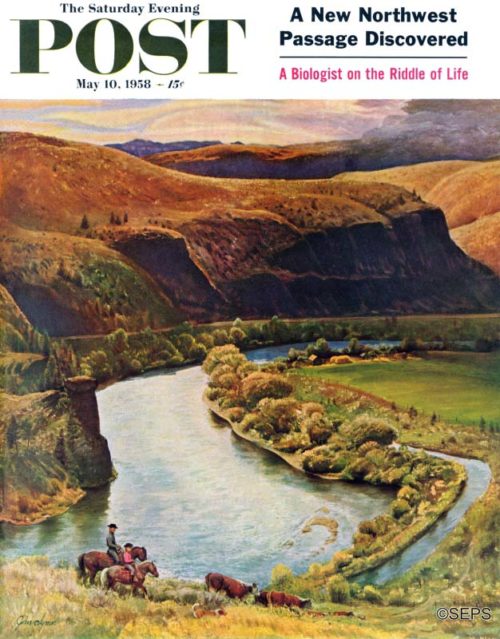

Yakima River Cattle Roundup

John Clymer

May 10, 1958

This is the Yakima River in Washington, not far from artist John Clymer’s boyhood home in Ellensburg; here, one side of the stream (see irrigation canal) is for farming, and the other side for looking. At this river bend Clymer and his father often fished for trout and, furthermore, caught same. In case this lovely spot gives you ideas about temporarily leaving home, just off the bottom of the cover is U.S. Highway No. 10.

Ohio River in April

John Clymer

April 15, 1961

Heading down the Ohio is a venerable stern-wheeler, push-towing barges loaded with coal and gravel. Cargo by the tens of millions of tons is shipped up and down the Ohio in this manner each year, between Pittsburgh, at the confluence of the Allegheny and Monongahela, and Cairo, Illinois, where the Ohio empties into the Mississippi. (The watershed of the Ohio reaches into fourteen states.) Artist John Clymer formed his riverscape by piecing together the water’s-edge scenes that appealed to him most. The near shore is West Virginia; the far shore is Ohio.

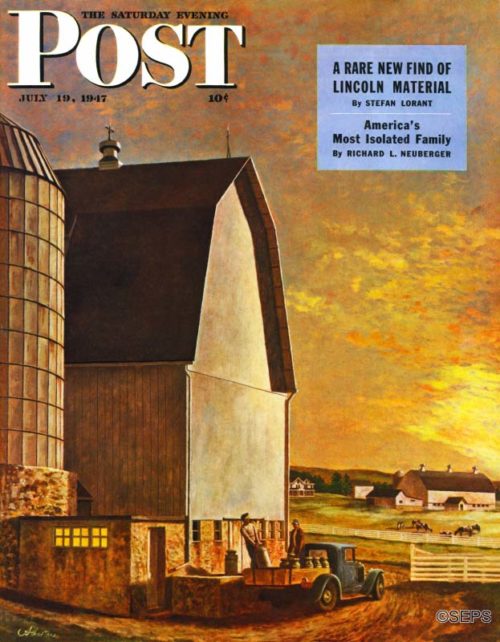

Dairy Farm

John Atherton

July 19, 1947

Artist John Atherton paints an early morning scene in the rich dairy country of Wisconsin, where if all cows are not contented they are hard to please. It’s a section as sleek as its cows, where life has a very high butterfat content. The farm Atherton chose is near New Glarus, in Green County, a town settled in 1845 by Swiss from Glarus, Switzerland.

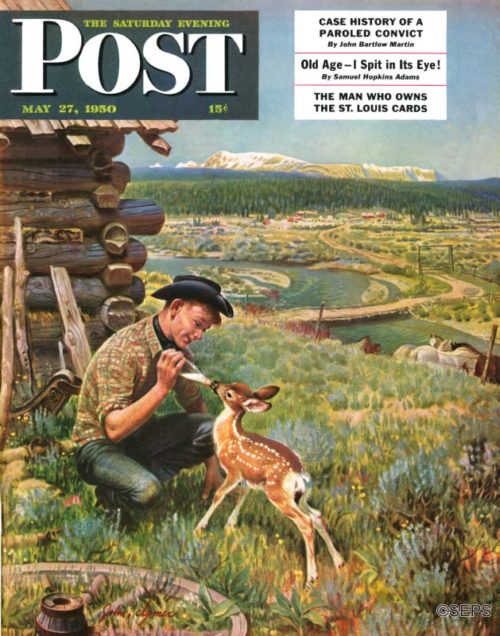

Feeding Fawn Near Flowering Field

John Clymer

May 27, 1950

Boys everywhere have pets; this variation of the pleasant practice is taking place in Wyoming. John Clymer kindheartedly omitted from the landscape the typical haystacks with ten-foot fences around them to persuade horses, cows, elk and high-jumping deer to go elsewhere in search of meals.

News of the Week: McEnroe’s Comments, Martha the Dog, and the Man Who Predicted Selfies

Serena Williams vs. John McEnroe

John McEnroe is known for saying things. He used to be known for yelling things, but he’s quieter now, though probably no less opinionated.

During an interview with NPR about his new memoir, But Seriously, the 7-time Grand Slam Singles winner said that if 23-time Grand Slam Singles winner Serena Williams played with male tennis players, she probably wouldn’t be in the top 700. Of course, this is the part of the interview that everyone has latched onto — which is probably good for book sales — and it got a reaction from Serena herself on Twitter (where everyone releases official statements now, apparently).

Dear John, I adore and respect you but please please keep me out of your statements that are not factually based.

— Serena Williams (@serenawilliams) June 26, 2017

I've never played anyone ranked "there" nor do I have time. Respect me and my privacy as I'm trying to have a baby. Good day sir

— Serena Williams (@serenawilliams) June 26, 2017

Serena gets points for using the phrase “Good day, sir.” We need to use that more.

Now, to be fair to McEnroe, it’s not like he brought this up out of the blue to insult Serena. He simply said during the interview that Serena Williams was the best female tennis player of all-time (in fact, he has said that Serena is one of the best athletes in history, period), and the interviewer asked him why he had to say “female” and not just “best” including men. What an odd thing to ask. Men and women are different (I realized this the first time I went to the beach) and that also extends to professional sports, too. Why can’t we talk about how good or bad an athlete is by separating them into different categories when the very sports themselves separate them?

Even Serena (and it’s funny how we simply call her by her first name, that’s how iconic she is) said during an interview with David Letterman that she couldn’t beat a man, someone like Andy Murray, because the women’s game is different than the men’s game. Men are stronger and faster. So I don’t think we can say that McEnroe is “wrong,” and he certainly wasn’t being misogynistic.

I do take issue with the number 700 though. She wouldn’t have a chance against someone ranked so low that nobody knows who he is? With her serve and mental strength, I bet she’d be in the match.

And the World’s Ugliest Dog Is …

There seems to be two types of dogs that compete in the World’s Ugliest Dog contest in Petaluma, California, every year. They’re either big and slobbering or goofy or small and, well, rat-like. This year’s winner is Martha, a 3-year-old Neapolitan Mastiff that weighs 125 pounds and clearly falls into the former category.

Come on, she’s not really ugly, she’s just … droopy.

RIP Gabe Pressman, Michael Bond, and Michael Nyqvist

Gabe Pressman was a legend of New York news, starting out his six-decade career at several newspapers, including the Newark Evening Sun and New York World Telegram and Sun before moving on to a long TV career at WNBC in New York. Except for eight years in the 1970s where he worked for WNEW, he was with WNBC from 1956 until his death. The Emmy-winning journalist died last Friday at the age of 93.

Michael Bond was the author who created Paddington Bear. He also was the author of a series of novels featuring Detective Monsieuer Pamplemousse. Bond died earlier this week at the age of 91.

Michael Nyqvist was so good at playing the bad guy, in movies like Mission: Impossible — Ghost Protocol and John Wick. He also played the lead in the Swedish Girl with the Dragon Tattoo movies and appeared in a cool sci-fi ABC show a few years ago, Zero Hour, that really should have lasted longer. He died Tuesday at the age of 56.

World Asteroid Day

It’s funny how we go about our lives and hardly ever think about what’s going on in the skies above us. I don’t want to alarm anyone, but there’s a chance an asteroid could hit us.

Today is World Asteroid Day, which is a good day for scientists and world leaders to think about doing something about the problem. NASA actually has a Planetary Defense Coordination Office, which sounds like an organization from a sci-fi movie. Last December a NASA scientist warned that the world really isn’t 100 percent ready for an asteroid or comet hitting our planet, though we are getting better at it. It’s probably best not to think about it.

In related news, CBS’s Salvation, a new summer series about a group of scientists who band together to stop an asteroid from hitting the earth, premieres on July 12. Perhaps you’ve seen one of the 50,000 commercials for it that the network has been running every day for the past two months?

People Really Dig Salvador Dali

It doesn’t seem fair to have no control of your body after you die. There you are, in the ground resting, your life on Earth over and done with, and all of a sudden people are digging you up and bringing your body back to the surface so they can examine it.

That’s what’s happening to surrealist artist Salvador Dali, whose body is going to be exhumed by order of a Spanish judge to settle a paternity suit brought by a woman who claims to be his daughter. The woman says that Dali had an affair with her mother, who worked as a nanny near Dali’s home.

Dali’s estate is worth hundreds of millions of dollars, but the woman says it isn’t about the money, it’s about finding out who she is and revealing the truth for her mother.

The Best Game Shows of All-Time

Well, look at this: an internet list that isn’t terrible.

Newsday has picked the 25 best game show of all-time, and it’s really a well-balanced list. Yes, I could argue — and I will argue — that shows like Love Connection, Deal or No Deal, and The Dating Game don’t deserve to be on any kind of best game show list, I’m impressed that most of the list is taken up by truly great, classic shows like The Price Is Right, To Tell The Truth, Password, The $64,000 Question, Jeopardy, Wheel of Fortune, and What’s My Line?

To replace the shows that shouldn’t be on the list I’d probably add Remote Control, Tic Tac Dough, Truth or Consequences, Scrabble, maybe Blockbusters, and how about Battle of the Network Stars, which came back to ABC last night?

We need more game shows on television. Just get rid of talk shows like The View and celebrity shows like Access Hollywood and they’ll be plenty of room.

Charles Schulz Predicted Selfies

The frequent Saturday Evening Post contributor was ahead of his time in many ways, including when it comes to picture-taking.

https://twitter.com/Peanuts_comics/status/878993191705296896

This Week in History: Jack Dempsey Born (June 24, 1895)

The world heavyweight champion boxer actually wrote an article for the August 29, 1931, issue of The Saturday Evening Post, on what happened behind the scenes before his losing battle with Gene Tunney.

This Week in History: Korean War Begins (June 25, 1950)

This Week in Saturday Evening Post History: “Peachtree Street” by John Falter (June 25, 1960)

John Falter

June 25, 1960

If I wasn’t a writer I’d want to be an artist or cartoonist, but I don’t have the skill for it. Even my stick figures look kinda funny. I mean, I can’t even begin to understand how John Falter created the way that he created, the mix of color and shadow, the way he gets the perspective right. There’s so much going on in this picture, so many places to look and explore, that it’s rather mesmerizing.

July Is National Ice Cream Month

With that Falter cover you know that I have to link to a recipe for peach ice cream, right? It’s from Southern Living and it’s officially called Summertime Peach Ice Cream. It looks easy to make too, just evaporated milk, condensed milk, half and half, sugar, and vanilla instant pudding mix.

Oh, and peaches. Don’t forget the peaches.

Next Week’s Holidays and Events

International Joke Day (July 1)

Here’s my favorite joke:

Knock-knock

Who’s there?

Interrupting cow.

Interrupting co …

MOOOOOOOOO

Wimbledon Begins (July 3)

Because she’s pregnant, Serena won’t be able to play the 700th man in the world or anyone else, but McEnroe will be one of the commentators when the tennis tournament kicks off on Monday, a week later than usual. You can watch the action live on ESPN (and on tape on Tennis Channel at night).

Independence Day (July 4)

In between the eating of burgers and the watching of fireworks, take a look at this collection of classic Saturday Evening Post covers that celebrate the day.

Cover Gallery: American Bridges

From San Francisco to Louisville to Pennsylvania, the beauty and grandeur of America’s bridges is on full display in these gorgeous covers.

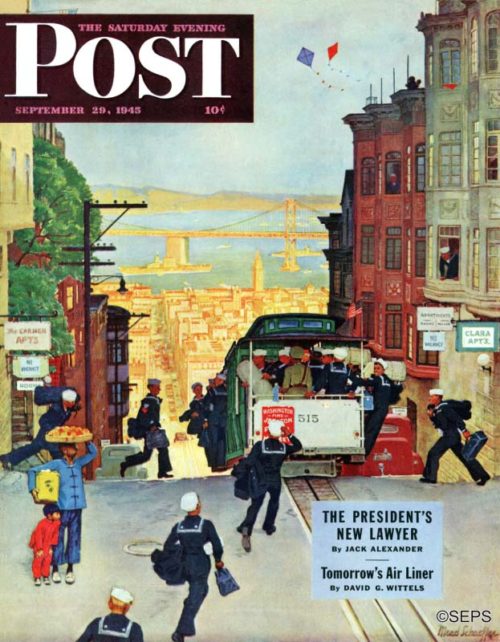

Mead Schaeffer

September 29, 1945

In August of 1945, the city of San Francisco announced plans to dismantle its famous cable car system. The Post was in the thick of the uproar that followed. Mead Schaeffer’s September 29 cover helped “touch off an explosive burst of civic pride” that ultimately saved the cars, as writer Elmont Waite recounts in this article published five months later.

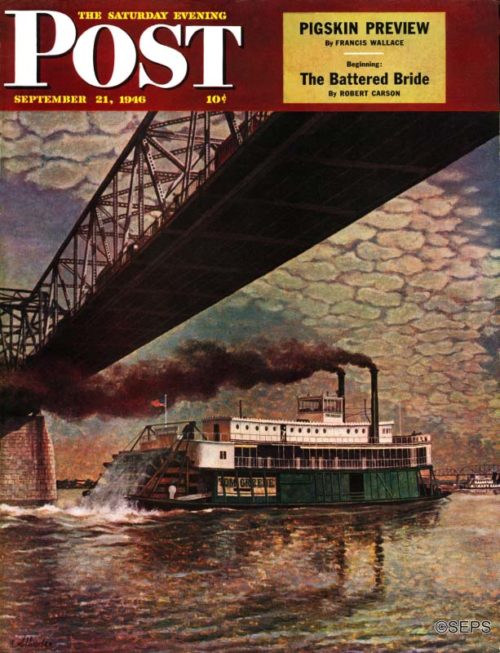

John Atherton

September 21, 1946

John Atherton painted his picture of the stern-wheeler at Louisville, Kentucky, where the Ohio rolls along on its way to join the Mississippi. Atherton enjoyed his stay in Louisville, but lost one of his illusions. A Vermonter, the artist went to Kentucky prepared to find that people there take things pretty easy. He had no sooner taken a preliminary squint at the river boat than a bustling Kentuckian took him in hand and arranged for the artist to work from a barge, which afforded a much better view. While relaxing at lunch, Atherton remarked that the job would take some little time, as he had to do a good deal of wandering up and down the river, in search of the proper site. A second energetic Kentuckian immediately put a car and driver at Atherton’s disposal, so the artist could cover more territory in less time. The motorized painter came back convinced that Kentucky is full of expediters.

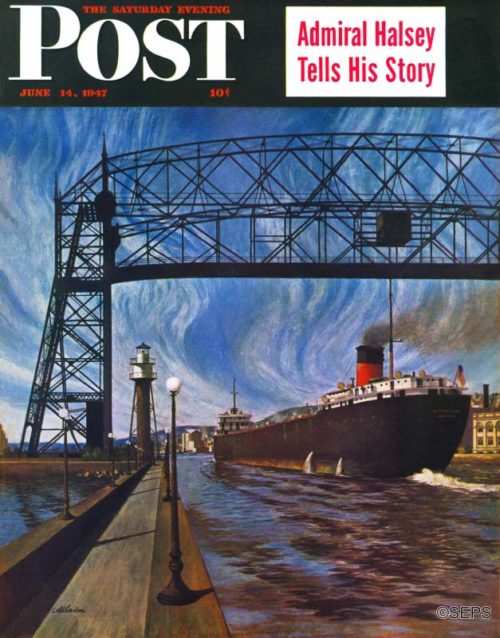

John Atherton

June 14, 1947

John Atherton’s cover painting is a continuation of our family album of American regions. This time he moved north, to the Paul Bunyan country, and thousands will not need to be told that the cover is a view of the husky city of Duluth. This is the ship canal, through which ore boats move out to begin their travels in the Great Lakes. The ore, of course, comes from the great Mesabi Range. Atherton chose a moment when the bridge had lifted to let one of the ore boats pass below. The trip to Duluth is one the artist had hoped for many years to make; he remembered being there as a boy of six, when he was deeply impressed. Not by Duluth’s Bunyanesque role in American industry, however, but with its excellent facilities for sledding.

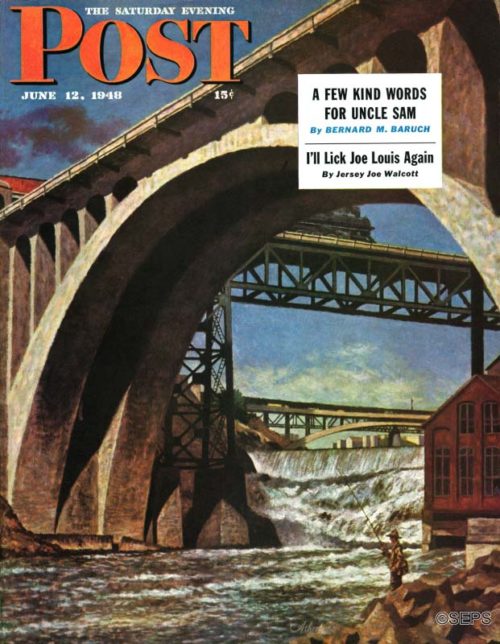

John Atherton

June 12, 1948

John Atherton’s cover painting is another page in our album of American localities; this time the scene is Spokane, and you are looking at the Monroe Street bridge, which is crossed overhead by a railroad bridge. Atherton lived in Spokane in his high-school days, and used to fish at the foot of these falls. In fact, when he needed a model for the fisherman, he dug out a photograph of himself at eighteen. It was the start of a lifelong devotion to fishing, not because Atherton himself had great luck in this river, but because he watched others haul out beautiful fish there—one rainbow trout that weighed nearly ten pounds. Atherton’s grandfather was an early settler and built a flour mill at the falls—the first in that region, Atherton believes.

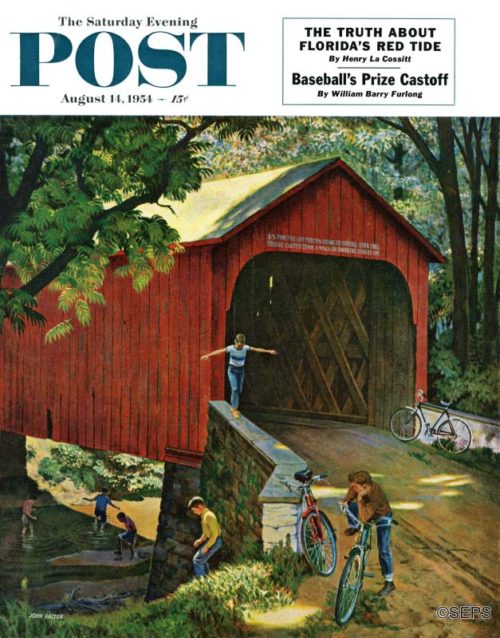

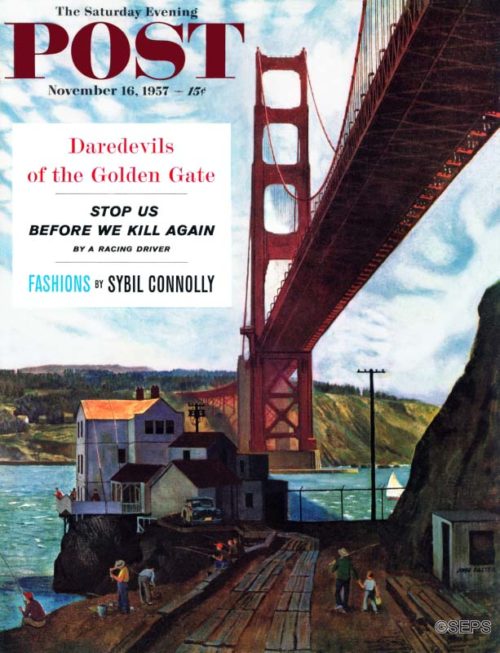

John Falter

August 14, 1954

A lazy summer day, a covered bridge, a crick or creek to play with, and a snake—how can one better define bliss? John Falter painted that bridge from life; its warning of “$5 fine for… smoking segars on” is an old rural Pennsylvaniaism, not a sample of the way the artist himself organizes words.

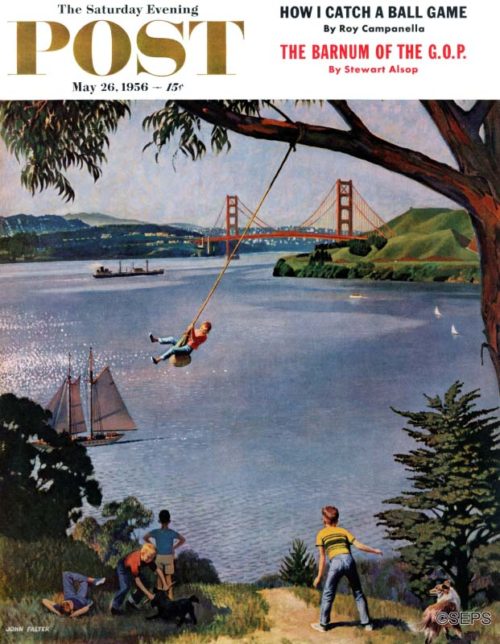

John Falter

May 26, 1956

When John Falter was strolling along Belvedere Island, admiring the grace of Golden Gate Bridge across the azure bay, he happily discovered that kids still relaxed in the mellow old hair-raising way. Falter’s cliffside home was two blocks to the right of his painting.

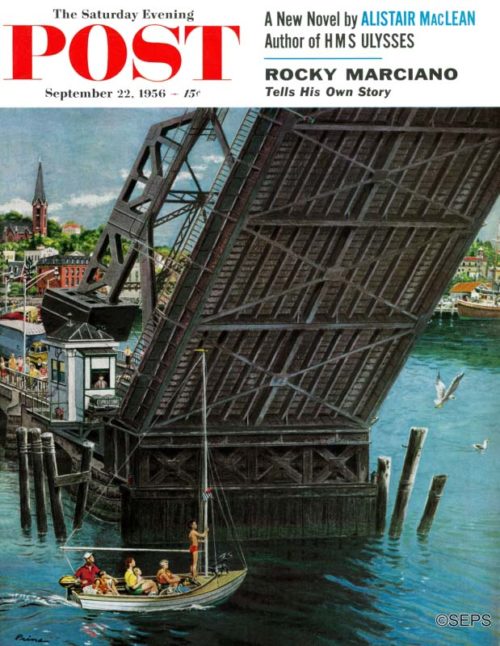

Ben Prins

September 22, 1956

Illustrator Ben Prins sat beside a drawbridge for three hours to watch it move, and it never moved a muscle, nothing wanting to go through but a gull. Finally, the kindly bridge tender, saying he’d better test the thing for shimmies anyway, waited till auto traffic was light and flapped it up and down for art’s sake. As no boats were visible, the motorists must have feared the man had gone on a bender.

John Falter

November 16, 1957

To the left across the water: San Francisco, plus the New York Giants. The house is a lighthouse and the cables keep it from taking off for a sail someday. John Falter, who said he was something less than a superb sailor, had helped crew sailboats out through the Gate a few times, and usually had been delighted to regain dry land.

News of the Week: Two Spaces vs. One, Boomers vs. Millennials, and House Hunters vs. Vintage Homes

A Typing Controversy

Like a lot of people of a certain age, I took a typing class in high school. I hated it and didn’t do well, which always makes me chuckle because now I actually type for a living, every single day. I think what I disliked at the time was having to sit a certain way, holding my hands in a certain position, endlessly recording the events of all good men who come to their country’s aid. Like a kid who just wants to play the guitar instead of learning chords or how to read music, I just wanted to type. Also, my teacher looked a lot like Larry Fine of the Three Stooges, and that distracted me.

One thing I remember from typing is you needed to put two spaces after a period. But that’s not really true online, and that has a lot of people who still like to put in two spaces a little, well, irritated. In this piece at Mel, amusingly titled “For the Love of God, Stop Putting Two Spaces after a Period,” John McDermott explains in detail why you should now only put one space after a period. In this follow-up piece, McDermott explains how a lot of people didn’t like to be told to put only one space after a period and let him know it in often colorful, vulgar terms (and often using only one space after a period).

I’ve never really thought about how many spaces come after periods in print books and magazines and newspapers. It does really stick out when I get an e-mail where someone uses two spaces. Now I’m going to really notice it, and it’s probably going to drive me batty.

Boomers vs. GenXers vs. Millennials

Every generation complains about the generation that preceded them. Millennials blame Generation X for everything, Generation X blames Boomers for everything, and Boomers blame The Silent Generation, who then blame The Greatest Generation. At least I think that’s how it goes. It’s hard to keep track of who is named what when and why.

I have a slightly different take. I’m a GenXer, and I’ve never blamed Boomers for anything. It never occurred to me to blame Boomers. Instead, like any normal GenXer or Boomer, I complain about Millennials.

BuzzFeed has the results of a poll conducted by the Ipsos firm that found out what older people and younger people think they should do to be considered an adult. The topics range from living at home and doing your own laundry to paying your own bills and having an annual medical checkup.

Shouldn’t all of these numbers be near or at 100 percent? Not every category for every age group, of course, but some of these numbers seem low to me. Only 39 percent of people aged 35–54 consider cooking for themselves more than twice a week to be a sign you’re an adult? Only 43 percent of those aged 18–34 think getting no financial support from their parents is a sign you’re an adult? Only 16 percent of everyone polled gets a flu shot? I’d love to see a similar poll taken in 1980 or 1960.

Some of the results shock me, but not as much as finding out that the word adult is now used as a verb.

And the Tony Nominees Are …

I could go into detail about this year’s Tony nominations. About how this person or this show got a lot of nominations or how this person was snubbed or what the nominations mean. But I haven’t seen any of the shows, don’t really know much about the shows, and I’ve never been to a Broadway show. But here’s the list of this year’s nominees. You probably know more than I do.

The awards show will air June 17 on CBS.

Strike Averted!

Three weeks ago, I told you about a possible writers strike that was about to hit Hollywood. But now we don’t have to worry about it because the two sides came to an agreement at the last minute on Tuesday. It’s a three-year deal that gives writers more money (including increases in residuals), expanded contract protection, and changes to healthcare.

Now, if you were actually hoping for a Hollywood strike, you might be in luck: An actors strike could be next.

Frozen in Time

Whenever I watch House Hunters I get a little irritated, for two reasons. One, I don’t really believe that the show is completely honest. The setups seem staged, and everything is a little too scripted (and a 2012 investigation seems to back up that theory). Second, I hate when the couples are shown an older home, maybe a midcentury home with its original rooms and design and appliances, and the first thing that comes out of their mouths is “we have to tear this out!” I hate that. Those homes should be owned by people who want to keep most of the original features intact.

Like the people shown in this Wall Street Journal piece titled “Life Inside a Time Capsule.” It’s about people who buy older homes and decide to keep them the way they’ve always been, almost like living their lives the way the previous owners lived theirs decades ago. The slideshow is terrific, even if some of the designs of the ’70s homes may disorient you for a moment.

RIP Florence Finch, Norman T. Hatch, Colonel Bruce Hampton, Lorna Gray, Trustin Howard, Leo Thorsness, and Bruce Hall

Florence Fitch was a World War II hero whose bravery wasn’t even known to the public until decades later. She actually died on December 8 at the age of 101, but her family didn’t make the announcement until this week.

Norman T. Hatch had a connection to World War II as well. He was a Marine cinematographer whose shocking footage of a battle in the Pacific won him an Academy Award in 1946. He died April 22 at the age of 96.