Walter Winchell: He Snooped to Conquer

If he is remembered, the journalist and radio man Walter Winchell evokes a few different types of memories. Baby boomers might recall the narrator of the 1959 series The Untouchables. Their children might have caught the HBO biopic Winchell that starred Stanley Tucci as the fedora-donning gossip columnist. Younger people likely won’t recognize the name Walter Winchell at all. But consider this: every time you guiltily click on a link promising a juicy scoop on a washed-up actor, Winchell is somewhere, smiling.

In his heyday, Winchell commanded a collective audience of about 50 million Americans — two-thirds of the adult population in the 1930s. As biographer Neal Gabler claims in American Heritage magazine, anyone walking the streets on a warm Sunday evening in any city in America at the time would hear Winchell’s staccato voice through successive open windows on their way, giving updates on the war in Europe or a famous couple who might be “infanticipating.”

Making and breaking celebrities and politicians in his syndicated columns and radio broadcasts, Winchell built a complicated legacy. Though he often leveraged his platform to give a voice to everyday Americans, Winchell’s lifelong quest for popularity became his own undoing.

A new PBS American Masters documentary, Walter Winchell: The Power of Gossip, offers viewers a new look at how, for better or for worse, Winchell created “infotainment.” The documentary tracks the gadfly’s rise during the Great Depression and his slow decline in the McCarthy era, with Whoopi Goldberg as narrator and Stanley Tucci reprising his role as Winchell.

Director Ben Loeterman says that he was drawn to Winchell’s story as a sort of explanation of the current state of news media: “I think understanding the origins of how news is shaped and delivered and the importance of story, that has become absolutely part of journalism today, started in that sense, I think, with Walter Winchell.”

Winchell’s career arc can be simply understood with his own words: “From my childhood, I knew what I didn’t want: I didn’t want to be cold, I didn’t want to be hungry, homeless, or anonymous.”

In his early years reporting Broadway gossip at Bernarr Macfadden’s New York Evening Graphic (a tabloid commonly called the “Porno-Graphic”), Winchell learned that “the way to become famous fast is to throw a brick at someone who is famous.” He quickly made enemies, namely the Schuberts, who banned him from their theaters. Winchell secured a hefty readership, though, with his euphemistic claims about Jazz Age New Yorkers. Soon enough, he was rubbing elbows with Ernest Hemingway, Al Capone, and plenty of others who feared and respected his power of the press. He regularly attended Manhattan’s Stork Club, where anyone who was anyone knew to find him.

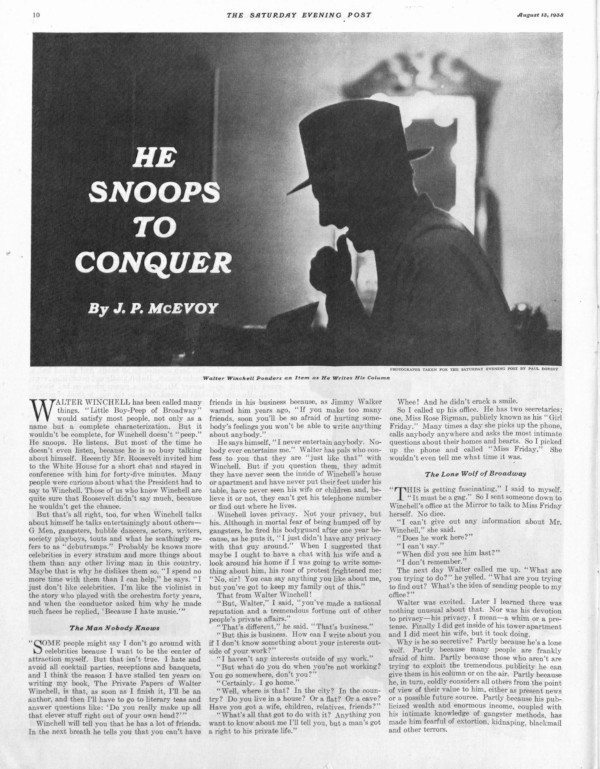

J.P. McEvoy turned a journalistic eye onto Winchell and his brand of “personal journalism,” writing the profile “He Snoops to Conquer” in this magazine in 1938. “Because he was fearless, talented, tireless and tormented by an unappeasable itch for success,” McEvoy wrote, “he arrived at his present peak — where he lives in a state of ingenuous surprise that he has arrived and a gnawing fear that he cannot remain.” Winchell was making about $300,000 a year at the time, between movies, radio, and his column at the Daily Mirror, which was syndicated to thousands of papers across the country. He had become famous for, among other things, coining provocative slang many called “New Yorkese.” H.L. Mencken, in The American Language, noted Winchell’s introduction of several words and phrases into the lexicon. Reno-vated (divorced), obnoxicated, Hard Times Square, intelligentleman. A young couple might be cupiding or “makin’ whoopee.”

Winchell’s reports weren’t limited to celebrity gossip, though. He was an early, outspoken critic of Nazism, taking shots at Hitler as a “homosexualist” called “Adele Hitler” (“he put a hand on a Hipler … ”) and regularly blasting antisemitic Nazi propaganda. When a German-American man named Fritz Kuhn began rallying Nazi sympathizers, first in the Friends of New Germany and later in the German-American Bund, Winchell found a nearer target for derision (“the SHAMerican”). Kuhn thought of himself as a sort of “American Führer,” organizing youth camps and rallies with the growing Bund in the ’30s. Right before more than 20,000 Nazis and Nazi sympathizers descended on Madison Square Garden in 1939 for George Washington’s birthday, Winchell tore into “the Ratzis … claiming G.W. to be the nation’s first Fritz Kuhn … There must be some mistake. Don’t they mean Benedict Arnold?” Winchell was delighted when Kuhn was sentenced to prison for embezzlement that year, writing about how the warden would be “the chief sufferer.”

At the start of President Roosevelt’s first term, Winchell praised the president as “the nation’s new hero,” sparking a close relationship with the administration that would prove fruitful for both of them. Years later, Post editor and former Roosevelt liaison Ernest Cuneo wrote all about how prominently Winchell had figured into their strategy to get FDR a third term (“Look, Walter,” I wanted to say, “you are the Third Term campaign.”).

Winchell was taken with President Roosevelt — and perfectly happy to act as a patriotic mouthpiece for the New Deal and American intervention in the war — but after Roosevelt left office, the gossip reporter found himself politically stranded. In 1951, Winchell affronted African-American performer Josephine Baker when he failed to defend her allegations of racism at his beloved Stork Club. Then, in 1954, he frustrated public health efforts by incorrectly announcing on his broadcast that a new polio immunization “may be a killer,” contributing to a dangerous anti-vaccination backlash. Winchell was really sunk, however, after he aligned himself closely with Joseph McCarthy and Roy Cohn.

“If he thought there was a star he could hitch himself to,” Loeterman says, “that was more important than the politics or any of the rest of it.”

Winchell transferred his disdain for Nazism into the anti-Communist witch hunts of the ’50s. He had vocalized his opposition to communism throughout his career, but McCarthy and Cohn made him an honorary member of a new — doomed — club. As Gabler put it, “he would lose because his populism had transmogrified into something cruel and unmanageable, just as his detractors had charged. Once a lovable rogue, Walter Winchell had become detestable.” He had brief stints on television in the ’50s, but nothing stuck. Winchell’s newspaper and radio routines were things of the past, and he had cultivated too much public distrust.

Although he faded from the public eye, Winchell’s mark was already made: the “welding” of news and entertainment. Two years after his death, People magazine was launched, and no shortage of commentators and gossips have haunted our screens and papers since. Kurt Andersen wrote in the Times about the evolution of Winchell’s personal journalism, “As star columnists leveraged their columns to accumulate personal celebrity and their personal celebrity to generate more readers, the market for their sort of journalism grew.”

If Winchell isn’t remembered, then he ought to be, if only so that we can more clearly understand that clickbait has a snappy, five-foot-seven predecessor who was one of the most famous men of his time.

Featured image taken by Paul Dorsey, The Saturday Evening Post, August 13, 1938

Remembering Titan of Journalism Pete Hamill

Legendary journalist Pete Hamill died yesterday at age 85. The illustrious writer was described as a “quintessential New York journalist” for his decades of work in The New York Post, The Daily News, The Village Voice, Esquire, The New Yorker, Playboy, and The Saturday Evening Post. He published short stories and novels too, along with a memoir and books of essays.

In newspapers, Hamill became known for his plainspoken columns, giving on-the-ground perspective of culture and justice in his home city. For this magazine, he travelled Europe in the early ’60s, sending back celebrity profiles and stories of crime and labor disputes.

Hamill’s knack for skillfully undressing New York City was clear in one of his earliest stories for the Post, “Explosion in the Movie Underground,” printed on September 28, 1963. Years before the New Hollywood era of cinema was declared, Hamill documented the experimental filmmakers working on the streets of New York. He was skeptical of some of the “amateurish and ill-conceived visual essays” that were being produced, but he described the guerrilla directors and their makeshift moviemaking with the kind of sincere, closeup reporting that was a hallmark of his work.

In another Post story, “The Great British Train Robbery” (September 19, 1964), Hamill covered the largest (at the time) cash robbery of all time, in which 15 men stopped a Royal Mail train and took off with more than 7 million dollars. He detailed the puzzling case of the 1963 Great Robbery and subsequent “Great Jail Break” that left British police scratching their heads and the public oddly impressed and intrigued.

Journalists and editors mourned Hamill’s passing. New York Daily News columnist Mike Lupica tweeted “As Pete once said of another New Yorker, it’s like a hundred guys just left the room,” and former New York Times writer Clyde Haberman tweeted “the world just became a far less interesting place.” Daily News reporter William Sherman wrote in an e-mail that Hamill was about the fastest writer he ever saw: “He had an preternatural understanding of the city and its people from the top hats on Fifth to the longshoremen on 12th at the River. He knew how to listen, which he advised us beginners as most important.”

In a phone call, Gay Talese recalled meeting Hamill while covering prizefighter José Torres in the late ’50s. “I’ve been living in New York for 75 of my 88 years,” he said. “I’ve known so many different writers, from poets to playwrights to journalists, and Hamill was a combination of all of those things, and he had the capacity for and time for friendship. I felt he was one of my best friends.” Talese said that Hamill’s life crisscrossed the lives of both the writing profession and nightlife: “I knew him when he was and wasn’t drinking and I couldn’t tell the difference because he was always a nice guy … he lived an extraordinary life.”

Hamill expressed his opinions on the Post in no uncertain terms soon after it folded in 1969 in a column in The Village Voice. He had visited the deserted offices on Lexington Avenue and gave a close account of the magazine’s downfall: criticism coupled with credit where credit was due for what he saw as the interesting work done in the ’60s. “At the end,” he wrote, “with the magazine collapsing around them, the Post editors finally saw fit to commission Norman Mailer to write something for them. It will never be printed by the Post.”

Hamill’s journalistic world of pounding out copy on a typewriter and throwing cigarette butts on the floor may be long over, but his intense passion for the truth, and his tendency to take to the streets to find it, is a lasting inspiration in every newsroom.

Featured image by David Shankbone, edited via the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license, GNU Free Documentation License, Version 1.2.

Remembering the Fallen of World War II

One of the most searing scenes of the 75th Anniversary of D-Day ceremonies last year was at the Normandy American Cemetery on the bluff overlooking Omaha Beach. Beautiful in its way, the grass in the 172.5 acres so green it might be in a Technicolor movie, the chalk white crosses and Stars of David on the graves — more than 9,380 — lined up in a symmetry that is breathtaking.

Beneath each cross and star lies a fallen serviceman, a G.I. we honor — every day, I hope, but especially on Memorial Day, the day set aside each year to remember the fallen. Rightly so, as the inscription on one marker puts it:

Into the great mosaic of victory

This priceless jewel was set.

So, too, the fallen in the Luxembourg American and Memorial Cemetery — 50.5 acres in Luxembourg, with 5,076 graves — one of the white crosses there marking the final resting place of General George S. Patton, “Old Blood and Guts.” He led his Third Armored Division 100 miles on icy roads in bitter cold weather in December 1944 to break the German encirclement of Bastogne in The Battle of the Bulge.

The deadliest U.S. battle of World War II, fought when the war in Europe was supposed to be over.

The surprise German attack had just started the day I approached the entrance to the Chicago Daily News Building on December 18, 1944, in hopes of getting a job as a copygirl at the Chicago Daily News. The Allied retreats each day, before the eventual advances, made up the headlines my first weeks there. Newspapers were all around me, editions delivered by copyboys coming up from the press room with the latest edition every couple of hours, distributing them to the various news desks and editors. Big black headlines were followed by stories with the details, notably the siege of Bastogne, which the Germans surrounded early on in the fighting.

Because the German attack pushed a long, deep curve in the Allied lines before the tide turned, it came to be known as The Battle of the Bulge. The daily battles, artillery shellings, and tank attacks left those rows of white markers in the Luxembourg American and Memorial Cemetery.

The war in the Pacific was equally costly.

It came into my life the morning of February 1. When I came to work I was told not to report to my usual post at the city desk but to go to a far corner of the city room, a square of four empty desks. On the cleared top was a stack of copy paper, a pair of scissors, a glue pot, and a streamer of Associated Press (AP) copy.

The streamer was not a story but a list of names of the men the Allies had just rescued from a Japanese P.O.W. camp in the Philippines — a military operation so dramatic, daring, and dangerous it came to be known as “The Great Raid.” A raid so dramatic, daring, and dangerous that John Wayne led the rescue mission in the 1945 film Back to Bataan. In a story in the late edition, AP put it this way:

SIXTH RANGER BATTALION CAMP, LUZON — (AP) — There is a long, dusty, twisting land near here which should become a war monument, for today it bridged two worlds. It leads across the plain toward the death camp where 513 prisoners of war were rescued by American Rangers and Filipino guerrillas.

To get the names of the rescued men out to their loved ones as quickly as possible, AP was listing them as they received them, not taking time to put them in alphabetical order. That was what I was to do.

I cut the names of the men apart, long narrow strips, and laid them out on the desk top. When a deadline approached, I reached for the glue pot and made a wide strip down the center of a sheet of copy paper, and stuck the names down. I remember that while they were secure, the glue did not reach the ends … and I can still see those ends curling up.

Copyboys would come for the list for the next edition and regularly bring me a new AP streamer with its list of names.

I finished just after lunch and settled in at my regular post at the city desk, ready to answer calls of “Copy!” and take stories to the copydesk or get clips from the library. And when things grew quiet late in the afternoon, I had time to read the latest edition, just dropped off at a nearby news desk.

Amongst all the happy photos of local families beaming at family pictures of their rescued sons or husbands, boyfriends or brothers, were the first stories about the men and the toll their years in the POW camp had taken.

There were those so weak, emaciated, a Ranger could carry two men on his back. Some limped from beriberi. The legs of some were scored by tropical ulcers and other diseases, and there were those who looked up helplessly from litters.

They talked in low tones of Japanese brutality and the Death March of Bataan, of the final terrifying week of bombing and bombardment that hit Corregidor, of men dying like flies, of disease, of ten hours daily in prison camps, under the hot sun in fields, or waist high in water of rice paddies under hard eyes, of frequent beatings and shootings.

They recalled when 10,000 men at the Cabanatuan prison camp used to spend all day strung out in line for a canteenful of water from one of the camp’s four spigots.

Now, they lined up for a supper of boned chicken, peas, beans, fruit salad, jam and cocoa — a veritable banquet after the starvation fare of the Japanese prison camp.

Invited to ask for more and eat all they want, one of the men said, “Where we come from they put you in the guardhouse if you asked for more.”

It was only with time that I realized each name on those AP streamers — soon a narrow slip of paper on the cleared top of the dark green metal desks — was the name of a man who had not only survived a Japanese POW camp but the Bataan Death March, one of the most horrific episodes of the war. So named because 10,000 of the 76,000 men who had surrendered when Bataan fell to the Japanese died during the five-day, forced march —66 miles in jungle heat to the Japanese prison camps. Some guards took the men’s canteens and emptied them of water so they would have nothing to drink. Others killed, bayoneted, and beat men who tried to get a drink from the gushing artesian wells they passed.

And so, while I don’t remember the names I alphabetized that day, I remember the men whose names were on those narrow slips of paper with the ends curling up — what they endured in their service to their country.

One of the survivors, Glenn Frazier, gave an account of the horrors in the Ken Burns documentary for PBS The War. It appears in the companion book, Frazier saying:

I saw men buried alive. When a guy was bayoneted or shot, lying in the road, and the convoys were coming along, I saw trucks that would just go out of their way to run over the guy in the middle of the road. And likewise the rest of the trucks, and by the time you have fifteen or twenty trucks run over you, you look like a smashed tomato. And I saw people who had their throats cuts because [the Japanese] would take their bayonets and stick them out through the corner of their trucks at night and it would just be high enough to cut their throats. And I saw men beaten with a rifle butt until there just was no more life in them. I saw Filipino women [who tried to bring us food or water] cut. Their stomachs were cut open. Their throats were cut. I saw Filipino and Americans beheaded just with one swipe of a saber.

An officer who’d been keeping track of the cut-off heads he saw as he passed stopped counting at twenty-seven lest he go mad.

Soon the headlines moved on again. This time, to Iwo Jima. The Marines landed there February 19.

The flag raising atop Mount Suribachi as they took control of part of the island would become one of the most famous pictures of World War II, or any war, for that matter. It would win the Pulitzer Prize for AP photographer Joe Rosenthal, go on to become a huge bronze statue — the centerpiece of the United States Marine Corps War Memorial in Arlington, Virginia — and an array of U.S. postage stamps through the years.

Many a headline reported the battle, the progress, the fierce resistance the Marines encountered, before the fighting ended March 26. But it was only when I read the book Flags of Our Fathers by James Bradley, son of one of the flag-raisers, that I fully appreciated what the Marines faced.

“The Marines fought in World War II for forty-three months,” Bradley said. “Yet in one month on Iwo Jima, one third of their total deaths occurred. They left behind the Pacific’s largest cemeteries: nearly 6,800 graves in all, mounds with their crosses and stars.”

Someone chiseled these words outside the cemetery on Iwo Jima:

When you go home

Tell them for us and say

For your tomorrow

We gave our today

Featured image: Marines raising the American flag on Iwo Jima, February 23, 1945 (photo by Joe Rosenthal / public domain)

Americans Should Not Fear the Media

This past year was a landmark year for ordinary citizens in the news. Without the hurricane survivors, student protestors, mass shooting victims, and sexual abuse survivors who agreed to speak to reporters, our understanding of some of the most important issues of the day would be murky at best. By giving firsthand accounts of what happened on the ground — or on the casting couch — before reporters arrived at the scene, citizen sources perform an important public service. But behind every citizen we see in the news is another story — about their interaction with journalists and the repercussions of their decision to go public — that audiences rarely know much about.

Occasional glimpses behind the scenes are telling — and troubling. A hurricane survivor bawls out a journalist in a video that goes viral. Student gun-control advocates later face cyberharassment and conspiracy theories.

I’ve spent the last 10 years interviewing ordinary people about what it feels like to become the focus of news attention. I spoke to victims, heroes, witnesses, criminals, voters, experts, and more. All were private citizens. Their stories raise important questions for journalists and audiences, and for anyone considering speaking to a reporter. They also hold important clues about media trust at a moment when online disinformation is a major concern, and public confidence in mainstream news has reached an alarming low.

Journalists control how people’s stories are told to the public: what is included, how it is framed, and who is cast as the hero or the bad guy.

Understanding how non-journalists see the news media is an essential step in rebuilding public trust. One of the most striking lessons I learned from speaking to citizen news sources is how differently they tend to see journalists from how journalists tend to see themselves. My interviewees mostly thought of journalists not primarily as citizens’ defenders against powerful people and institutions, but as powerful people and institutions in their own right.

Journalists seem powerful to ordinary citizens for several interrelated reasons. The first is that journalists have a much larger audience than most people can reach through their social networks. Journalists can be gatekeepers to publicity and fame. But, most importantly, they control how people’s stories are told to the public: what is included, how it is framed, and who is cast as the hero or the bad guy.

Those decisions can have favorable or destructive consequences for the people they are reporting about — consequences that are magnified online. And yet, journalists seem to dole out those benefits or damages pretty cavalierly.

To many non-journalists, the news media’s relationship to the public seems fundamentally unequal, and potentially exploitative. Ordinary people who make the news experience that inequality firsthand. Even when journalists are compassionate, friendly, and professional, the structure of the encounter usually feels lopsided.

News subjects are usually more deeply invested and involved in newsworthy events than journalists. That’s why journalists seek them out. Subjects were there when the shots rang out or were on intimate terms with the deceased. They feel these are their stories.

And yet, journalists swoop in to gather what they need in a process that feels both invasive and mysterious. Often, people decide to speak to reporters because they see it as an opportunity to address the public about an important issue, or enjoy the benefits of publicity. But the price of inclusion in the news product is control over how their story is told. Journalists quickly move on to the next story. Subjects stay on the ground to clean up the rubble and bury the dead — and manage the impact of the news coverage on their lives.

At a time when everything is googleable, that impact is exacerbated by online publication in two main ways. The first is that mainstream news articles perform very well in online searches. Old articles, once relegated to basement archives, now pop right up when you search for someone’s name and stay there possibly forever. Speaking to the press about sexual harassment, for example, was always risky. Today it brings with it the prospect that anyone googling you in the future — employers, landlords, students, dates — will know about that episode in your life.

Cyberabuse is the other big problem. Studies find online harassment is increasingly common. The controversial issues and breaking news events that thrust ordinary citizens into the media spotlight tend to trigger strong sentiment. That has long been true, but, before the internet, it took more effort to contact people named in news stories. Today we consume news on the same devices we can use to contact those people. Many of my interviewees reported receiving social media messages from strangers — some supportive, some abusive — as well as seeing themselves become fodder for online commentary. Not all news stories trigger digital blowback, but I have found that controversial stories almost always do.

Despite the unforeseen consequences of their news appearances, most of my interviewees liked the reporters who wrote about them and felt they had benefited from the experience overall. But in most cases, that one positive experience appeared to do little to shake their negative attitudes toward the news media as a whole.

For example, a woman I’ll call Ruby, who had survived a gang shooting in Harlem, described the reporter who had interviewed her as “gutsy, friendly, honest.” But she thought he was the exception to the rule.

That reporters don’t always take unethical advantage of their position was a welcome discovery to some interviewees, but it was not nearly as salient as the feeling that they always could.

Caty (another pseudonym) summed up the sentiment well. A New York City restaurant owner, she believed her business, threatened with closure, had been saved by a sympathetic news article. On the surface, hers was a classic story of a journalist defending a citizen against an oppressive bureaucracy. Caty was grateful to the newspaper and the reporter. But our interview ended like this:

Q: Is there anything else you think I should know?

Caty: My biggest thing is, the press has so much power. They should know the power they hold, and they should be ethical. The doctor is there to take care of a patient, over anything else. The press is there to tell the truth. And that’s been lost.

To many of the people I have interviewed, like Caty, the news media was a powerful entity that hulked over the citizenry. It was supposed to look out for citizens but often took advantage of them instead.

In short, it was a bully.

That helps explain why, shocking as it may seem, people may find it cathartic to see a news subject lash out at a reporter, whether it’s a hurricane survivor, a congressional candidate … or even the president of the United States.

The idea that many citizens feel like David to the news media’s Goliath may be hard for journalists to stomach or believe. It is the exact opposite of how journalists normally think of themselves. In their view, the news media works and fights on behalf of the people. Journalists are David, facing down the powers that be in the name of the citizens.

And yet, if news institutions want to regain long-waning public trust, they need to address the widespread perception that the news media is more interested in serving itself than the public. They would do well to highlight not just their accuracy, but their care, empathy, and ability to listen to the little guy.

This article is featured in the January/February 2019 issue of The Saturday Evening Post. Subscribe to the magazine for more art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.