The Art of the Post: The Rockwell Cover that Led to a Marriage

Modern art critics have often looked down their noses at Norman Rockwell’s realistic style of painting, dismissing his painstaking details as unnecessary and old fashioned. But for at least one person, the details in Rockwell’s painting led to a life-altering experience.

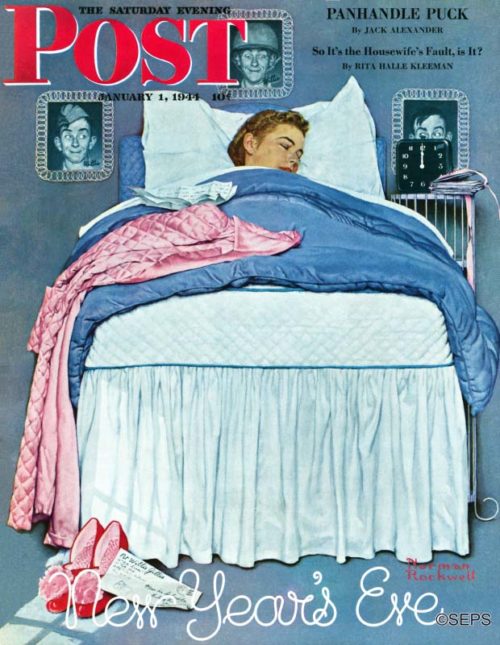

In this 1944 Post cover, Rockwell painted a pretty young girl asleep in bed at midnight on New Year’s Eve. Rather than go out partying, she dreams about her soldier boy overseas.

Rockwell literally selected the girl next door for his model. He asked his close friend and fellow illustrator, Mead Schaeffer, if Schaeffer’s sixteen-year-old daughter Lee would pose for the cover. Schaeffer lived just up the street from Rockwell in Vermont.

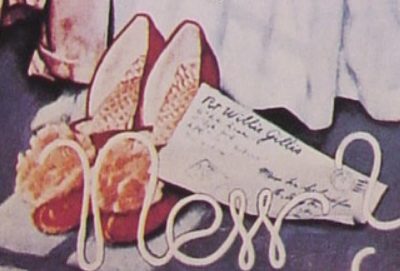

Ever the perfectionist, Rockwell also selected just the right details to tell his story. That clock on the bedside table shows us that it is midnight and the young girl is not out celebrating in those fancy party shoes. The photos of her boyfriend — none other than Rockwell’s favorite GI, Willie Gillis — on the wall tell us why. But do extra details such as the envelope on the floor really make any difference?

Rockwell was such a stickler for detail, when he painted that envelope he used Lee Schaeffer’s actual address. He assumed it would be too small and blurry to be legible when it was finally reproduced on the cover of the Post. The address was just one of the many details that Rockwell captured purely for his own satisfaction.

Unfortunately, Rockwell underestimated the resourcefulness of our young G.I.s. Soldiers were so smitten by the lovely Lee that they got out their magnifying glasses. Before long, letters started streaming in to Lee Schaeffer at home. Lee’s mother became quite upset with Rockwell for putting her daughter’s address on the cover of the Post. She made sure that all of Lee’s fan mail went unanswered.

But that’s not the end of the story. A few years later, a young veteran named Bob Goodfellow, recently back from serving in the U.S. Navy Reserve on Iwo Jima, saw the famous cover. Like others before him, he fell in love with the slumbering girl. But unlike other soldiers, Goodfellow had an advantage. His fraternity brother knew the Schaeffer family and happened to be dating Lee’s sister Patricia. Goodfellow kept pestering his fraternity brother to arrange an introduction, and finally his persistence paid off. The fraternity brother gave in and arranged a double date with Lee and Patricia in New York City. Goodfellow met Lee on a blind date on December 3, 1949. Goodfellow must have made a good first impression because he was able to wrangle an invitation to Mead Schaeffer’s New Year’s party. There, Lee introduced Goodfellow to her parents, he passed the test, and the courtship began.

Goodfellow and Lee Schaeffer were married on March 16, 1951, and they remain happily married in Vermont today. Next March will be their 67th anniversary. The famous Rockwell cover of the Post that started it all is framed and hanging on the wall above Goodfellow’s desk.

Many modern art critics have insisted that the tiny details in Rockwell’s paintings are pointless. They should keep their eyes and minds open. You can never tell where paying attention might lead.

The Art of the Post: Mead Schaeffer Paints America

Back before Google Maps gave us satellite images of every corner of America, there was Mead Schaeffer.

Schaeffer (1898–1980), whose cover illustrations appeared from 1942 to 1953, was one of the most highly regarded cover artists for The Saturday Evening Post. During World War II, he became famous for his war covers, but as the war ended, he needed to find a new theme. Soldiers were returning home to small villages and hamlets across the country, and the nation’s focus was returning once again to domestic life. Schaeffer’s wife, Elizabeth, who also served as his business manager and photographer, suggested that he paint a series of “regional covers” focusing on daily life in post-war America.

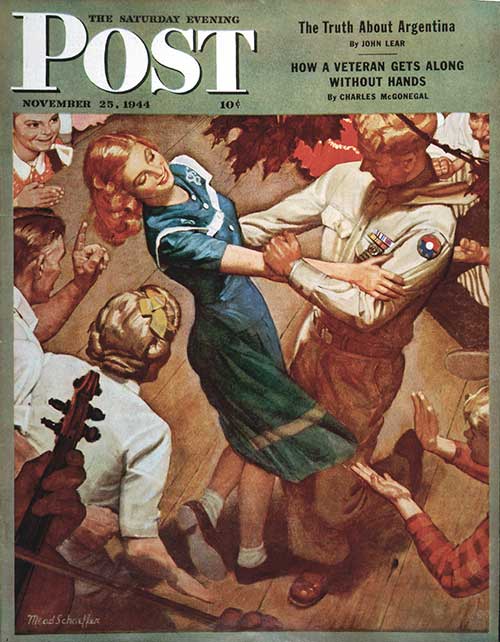

The Post jumped at the idea, and soon the Schaeffers were on the road, looking for scenes to feature on the cover of the magazine. His first cover in the series, published in November 1944, was a rural barn dance.

November 25, 1944

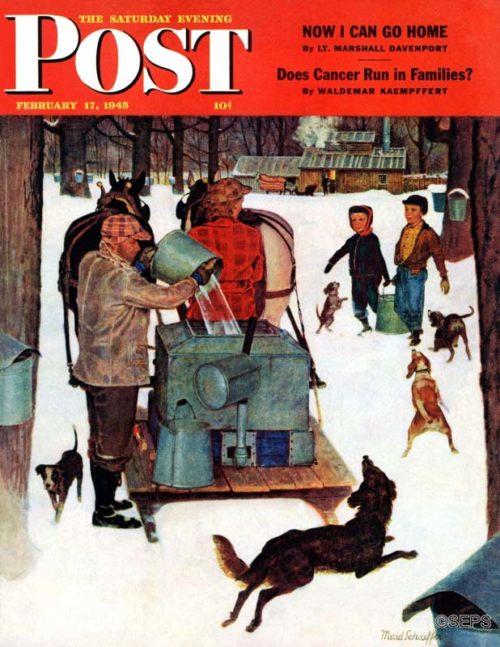

This was followed in February by a winter scene of Vermont citizens making maple syrup.

February 17, 1945

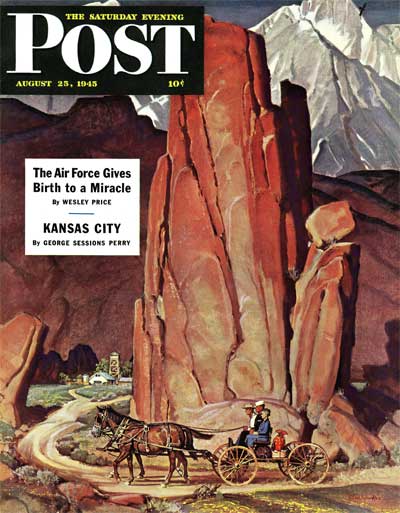

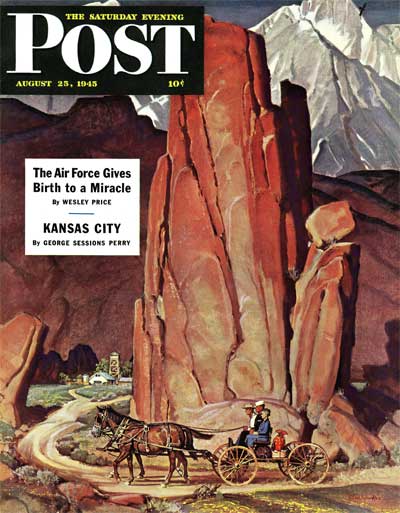

Next, he painted a sailor returning to his family ranch in Lone Pine, California.

August 25, 1945

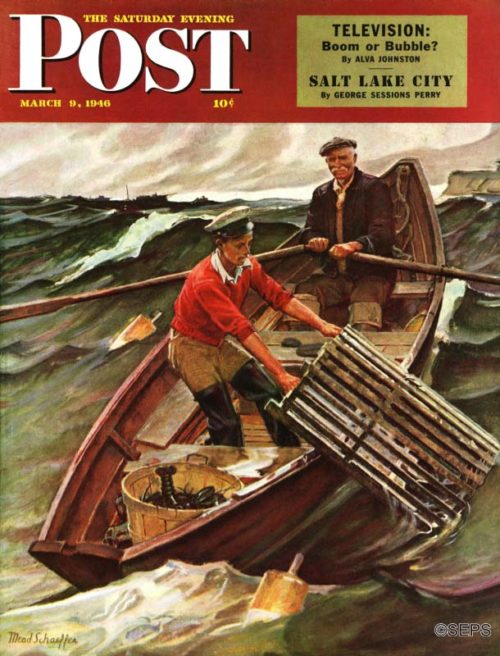

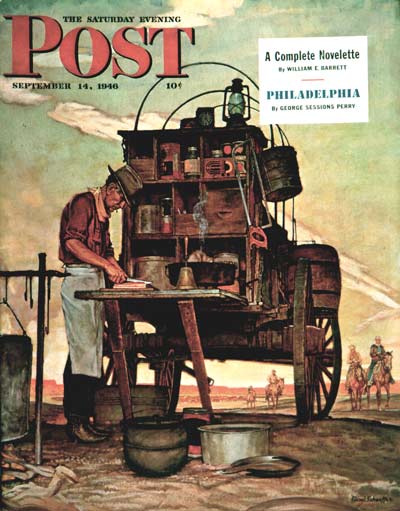

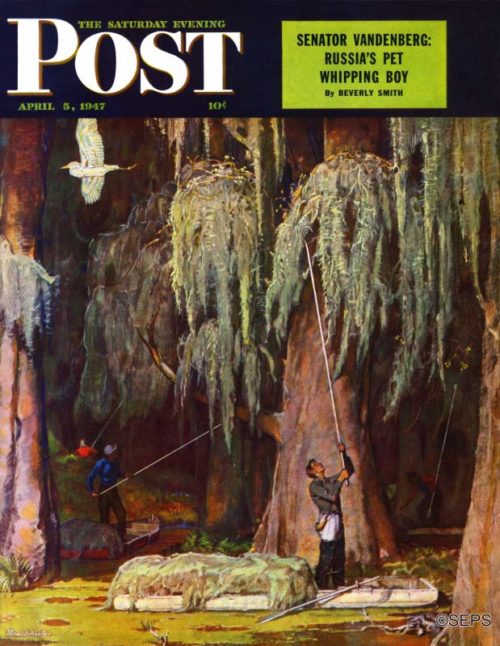

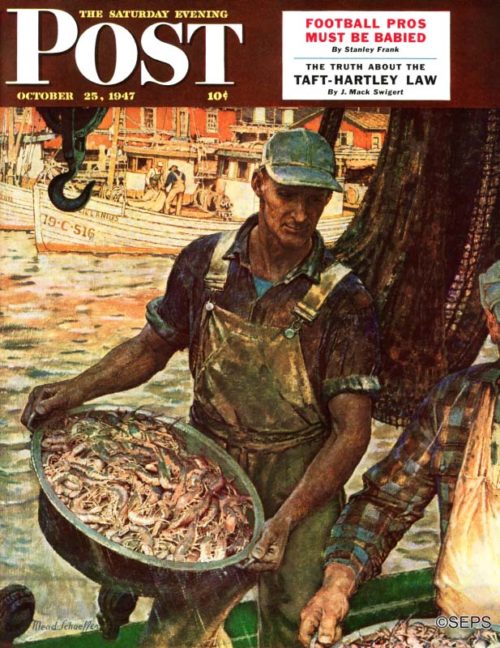

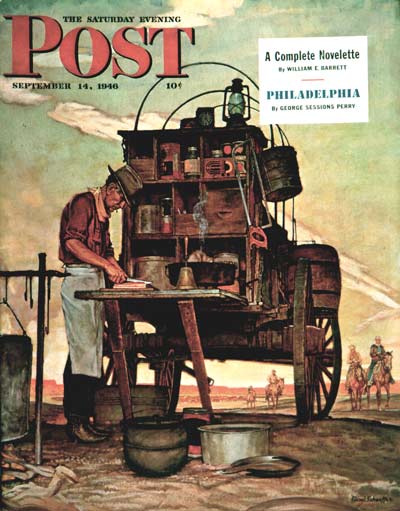

And in quick succession, he depicted a Maine lobsterman, a chuckwagon cook in Texas, moss pickers in Louisiana, and shrimpers in Mississippi.

March 9, 1946

September 14, 1946″

April 5, 1947

October 25, 1947

The Post called these covers “our family album of American regions.” Illustration expert Fred Taraba wrote in Masters of American Illustration that this series was designed to give viewers “a sense of the overall grandeur and diversity of the U.S.”

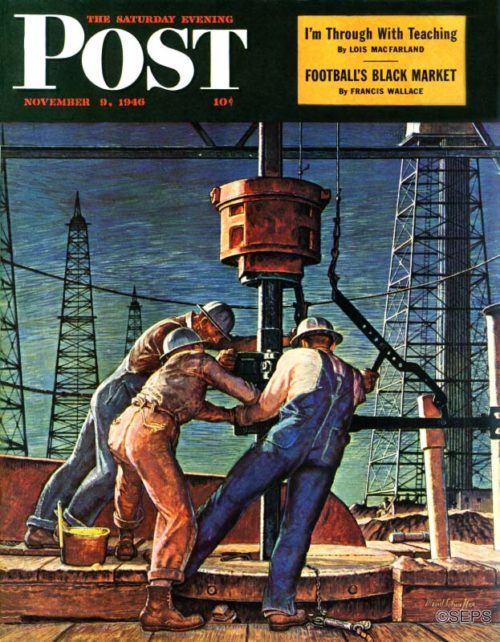

The regional covers became so popular that they created unexpected complications for Schaeffer: Communities began competing for his attention. When Schaeffer and his wife flew to Oklahoma City to paint workers on an oil rig, they were intercepted at the airport by a police motorcade, which gave them a tour of the city to show off possible sites for paintings. Local officials then escorted the couple to a plush hotel, where the mayor informed him the city would pay for all his expenses and transportation. The mayor next tried to set up a series of public appearances, but Schaeffer fended them off and spent a week painting on a grimy oil rig.

November 9, 1946

When he arrived in North Dakota to paint the Little Muddy River, Schaeffer was ushered into the capitol to meet the governor, who wanted to make sure his state would be well represented on the cover of the Post.

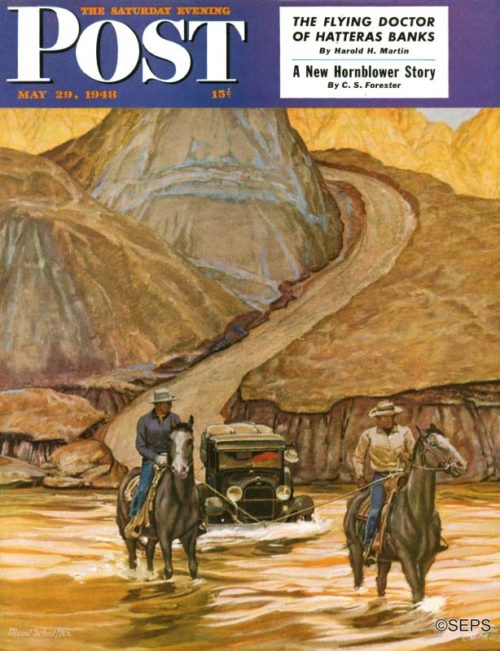

May 29, 1948

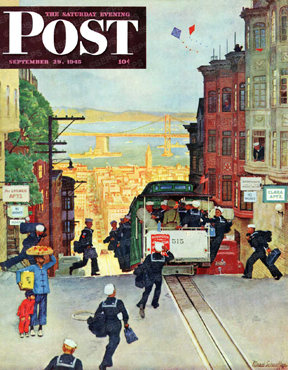

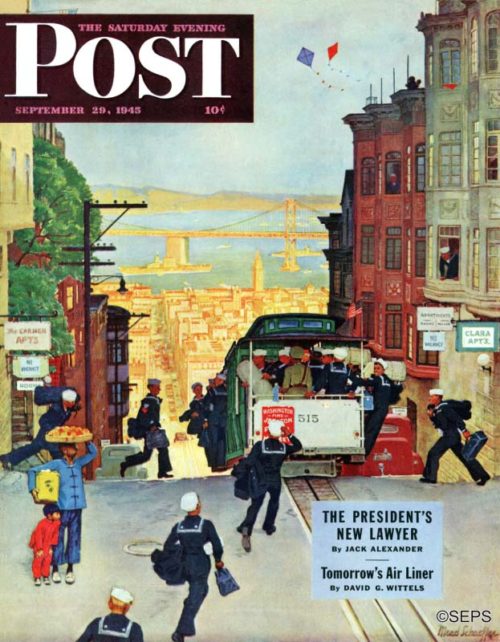

September 29, 1945

Schaeffer’s regional covers introduced a national audience to parts of the country they’d never seen before. TV only offered grainy black-and-white images, and there was no internet in those days, but Schaeffer’s sharp, realistic paintings gave the nation images to preserve in their memories. Most of all, delighted readers who lived in the region selected for the cover would go over every detail and write to the Post commenting on accuracy or making suggestions. They rarely found mistakes, thanks to Schaeffer’s passion for “getting it right.”

The Post was one of America’s most popular “general appeal” magazines, designed to be read by the country as a whole. And its weekly efforts to identify the largest common core of the country might have helped homogenize the nation. In later years, there was some concern that even the Post was becoming more eastern and elitist in its focus. That’s one reason why the magazine welcomed Schaeffer’s regional series. It was perceived as way of rejuvenating the Post’s nationwide outlook. Communities from all around America felt legitimized and important when they appeared in Schaeffer’s paintings on the cover of the Post.

Learn more about artist Mead Schaeffer.

See more of David Apatoff’s art columns.

Cover Collection: Farmers of the 1940s

In honor of National Farmer’s Day, we share some of our favorite illustrations of the people who worked the farms of America in the 1940s.

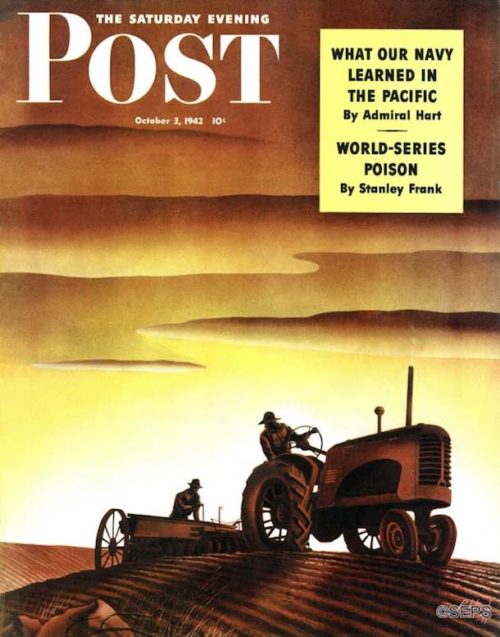

Arthur C. Radebaugh

October 3, 1942

In a year when many of the Post covers featured war-related images, this glowing, pastoral scene must have been a soothing one to readers. This painting reflects the regionalist style that was popularized by artists such as Thomas Hart Benton and Grant Wood. However, most of Radebaugh’s paintings were more futuristic; he created numerous illustrations for the airline and automotive industries.

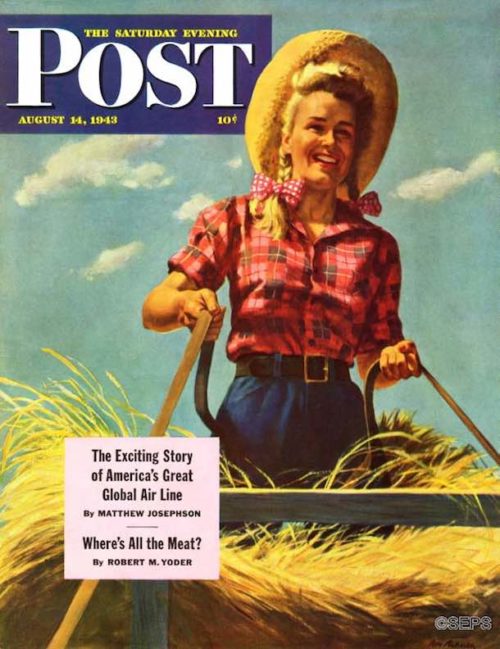

Ray Prohaska

August 14, 1943

Although he painted several interior illustrations for the Post, this was Ray Prohaska’s only cover. The woman atop the wagon with her straw hat, polka-dot hair ribbons, and plaid shirt is the quintessential farm girl. As with the previous cover, this happy scene gave readers a respite from the war.

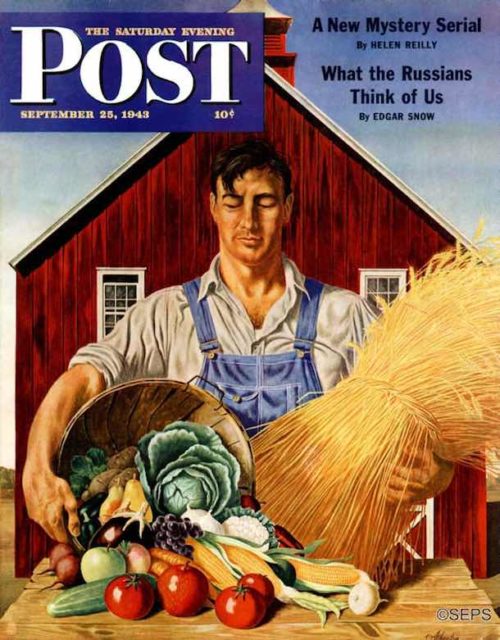

John Atherton

September 25, 1943

John Atherton painted 40 covers for the Post. Many were bold, architectural compositions of industry — steel mills, grain elevators, ore mines, and lumber yards. Atherton painted a number of more pastoral scenes, such as this farmer with his cornucopia of fruits, vegetables, and grains.

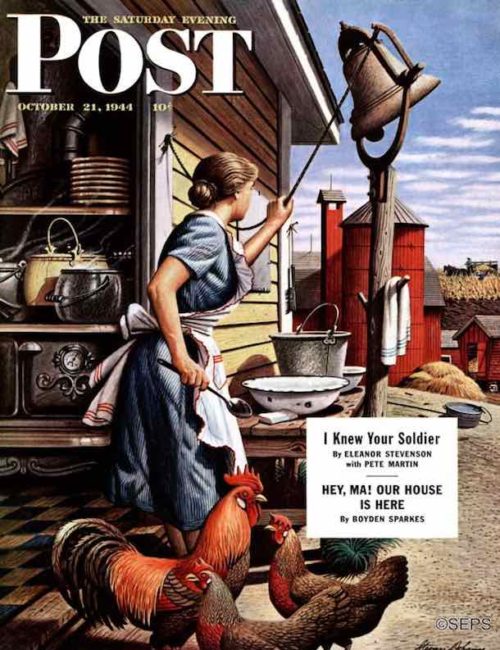

Steven Dohanos

October 21, 1944

Stevan Dohanos, inspired by Norman Rockwell’s talent, depicted everyday life in the 123 covers he created for the Post. Dohanos was also busy aiding the war effort by painting recruitment posters and wall murals for federal buildings. He also designed stamps for the federal government, starting during the Roosevelt administration, and staying in the profession the rest of his life.

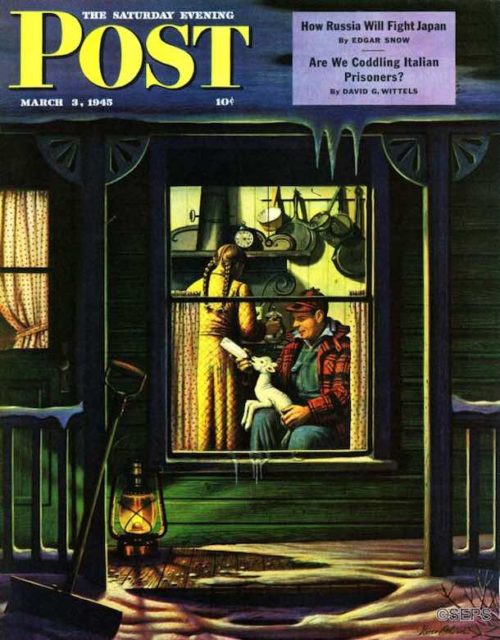

Stevan Dohanos

March 3, 1945

Stevan Dohanos made pencil studies of the lamb in this painting early in December on the farm of Raymond Platt, in Redding, Connecticut. Before he found his cover subject, however, he made a number of sketches in a drafty shed where lambs and ewes of all ages were quartered. “They stepped on my sketches and equipment; they pushed me all over the shed,” says Mr. Dohanos. “In fact, they acted just like people.”

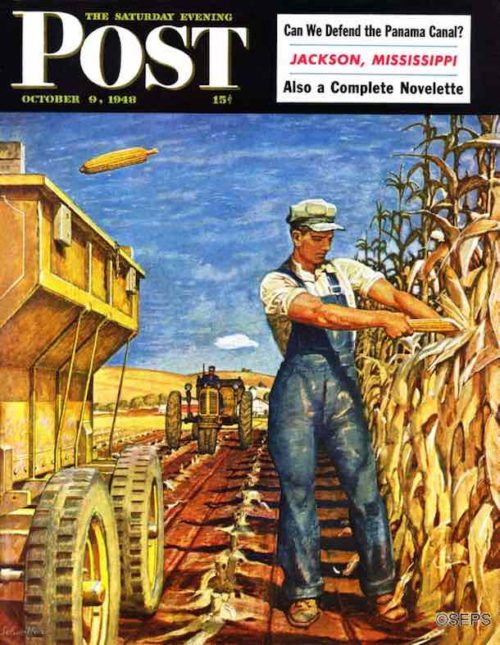

Mead Schaeffer

October 9, 1948

This Mead Schaeffer cover shows corn being picked by the “bang-board” method, which allowed a man to throw ears into the wagon without looking, because they would bang against a high board at the far side of the wagon and drop in. By 1948, most big farms used mechanical corn pickers, including the Lawton, Iowa, farm of Louis Peterson, the setting of this picture. The mechanical picker had already been used on much of the field, as the rows of stubble indicate, but the day Schaeffer was there, the machine was busy elsewhere. Farmer Peterson needed a little corn for his hogs. He got it the bang-board way—and Schaeffer got this cover.

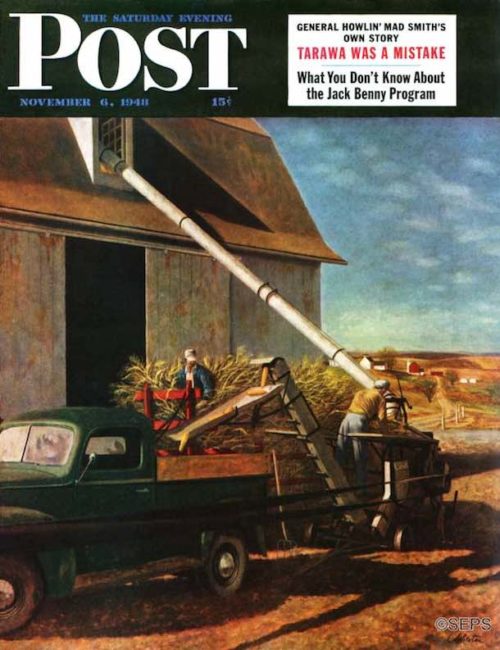

John Atherton

November 6, 1948

John Atherton’s cover painting depicts life on a farm near Madison, Wisconsin. The machine is a husker and shredder, which sends the husked ears of corn into the waiting truck, chops the stalk and blows the choppings into the mow, like hay. The power comes from a tractor offstage to the left.

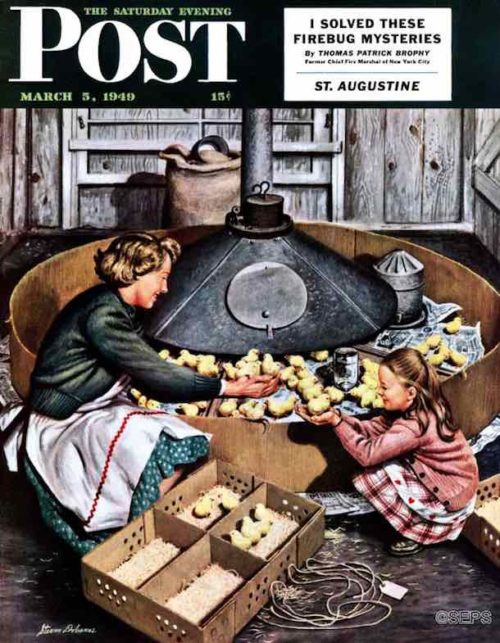

Stevan Dohanos

March 5, 1949

Stevan Dohanos felt apologetic about the request he made in a hatchery in Wallingford, Connecticut. “What I’d like to paint,” he said, “is baby chicks of one particular color. It’s a color people like to see on a bleak March day—a kind of pale lemon yellow.” It didn’t faze the hatchery men. “We’ve got about any shade you like,” they said, and began showing stock. The ones Dohanos chose—he thinks—were White Leghorns. The artist ended up pretty proud of his new knowledge. “That’s a coal-stove brooder,” he said professionally, “and technically correct. It has to be round. If it were square, you see, the chicks would get into the corners and crush themselves.”

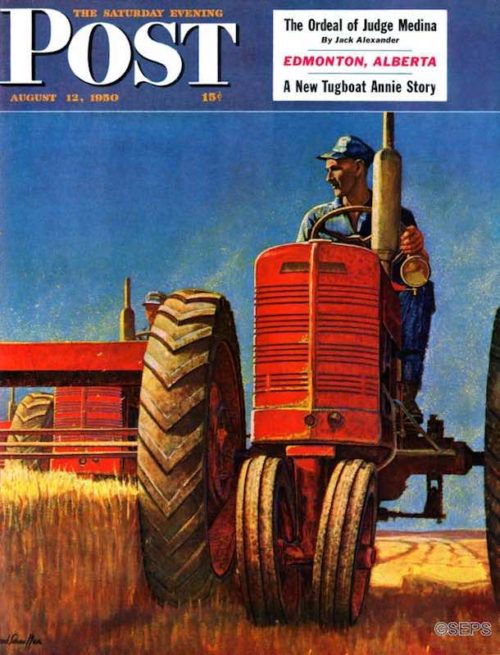

Mead Schaeffer

August 12, 1950

This cover is meant to coincide with the wheat harvest in the famous North Dakota-Minnesota Red River Valley. Artist Schaeffer, conditioned to small patches of Eastern wheat, was amazed by the endless golden seas of Midwestern grain. One day, in the fields, Schaeffer wondered where everybody’s lunch was coming from, and an airplane appeared, bringing same.

The Invention of Camouflage 100 Years Ago

Armies lost the ability to conceal themselves when the airplane appeared above the battlefields of World War I Europe, so soldiers came up with a defense against aerial snooping, and introduced a new word to the English language.

“Camouflage” by Will Irwin, September 29, 1917

It is pronounced, at present, French fashion, like this — “cam-oo-flazh.” In the theatrical business it signified makeup. The scene painters of the Parisian theaters carried it with them to the war and fixed it in army slang; for just about that time the armies of Europe began to introduce a new branch of tactics into warfare. By the end of the first year, most of the guns and motor transports used near the line were striped with greens, browns, dull yellows; sometimes with pinks and blues. But the stripes were not regular. All lines of union were wavy or broken. Nor did the colors meet each other sharply. For a little distance they were blended. It looked more, perhaps, as though someone had poured a few bucketfuls of paint, hit or miss, over guns and transports.

It is pronounced, at present, French fashion, like this — “cam-oo-flazh.” In the theatrical business it signified makeup. The scene painters of the Parisian theaters carried it with them to the war and fixed it in army slang; for just about that time the armies of Europe began to introduce a new branch of tactics into warfare. By the end of the first year, most of the guns and motor transports used near the line were striped with greens, browns, dull yellows; sometimes with pinks and blues. But the stripes were not regular. All lines of union were wavy or broken. Nor did the colors meet each other sharply. For a little distance they were blended. It looked more, perhaps, as though someone had poured a few bucketfuls of paint, hit or miss, over guns and transports.

This article is featured in the September/October 2017 issue of The Saturday Evening Post. Subscribe to the magazine for more art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

Cover Gallery: Hit the Slopes!

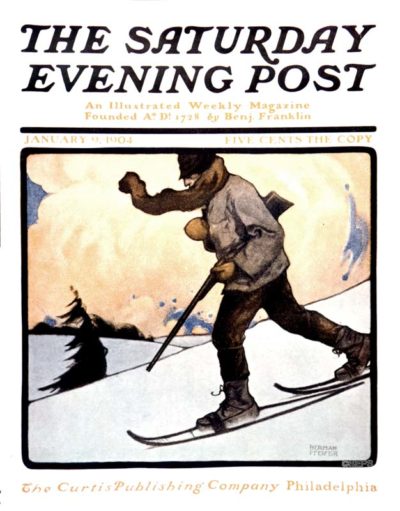

Heinrich Pfeifer

January 9, 1904

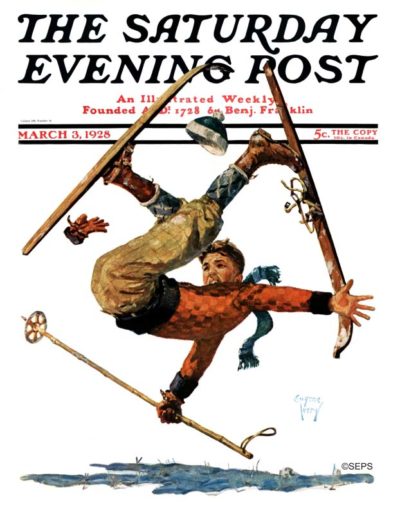

Eugene Iverd

March 3, 1928

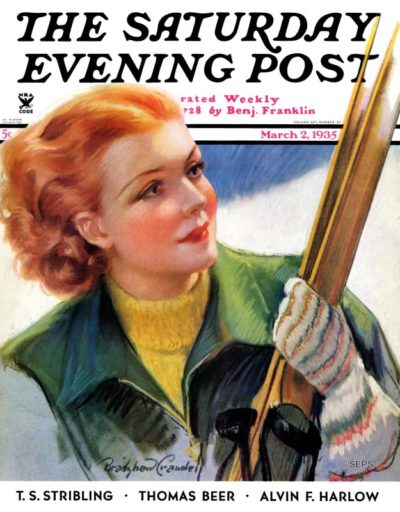

Bradshaw Crandall

March 2, 1935

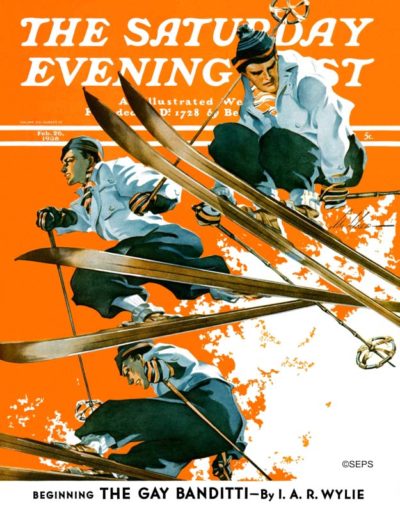

Ski Weld

February 26, 1938

Walt Otto

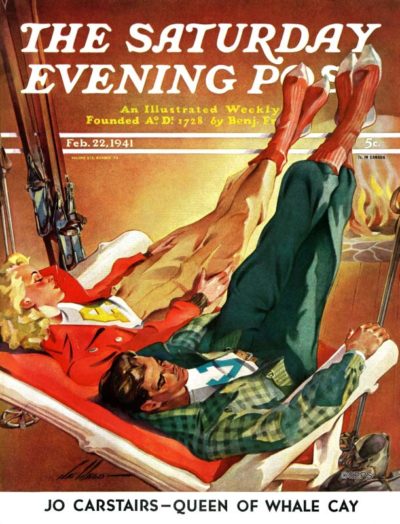

January 28, 1939

February 22, 1941

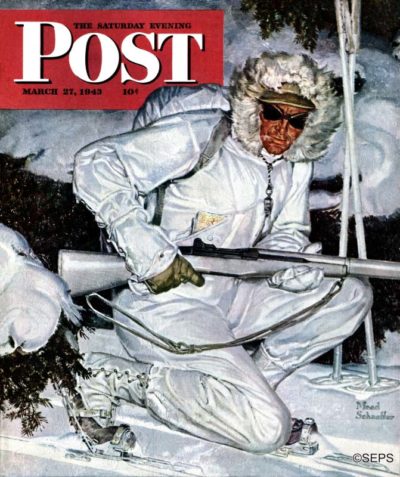

Mead Schaeffer

March 27, 1943

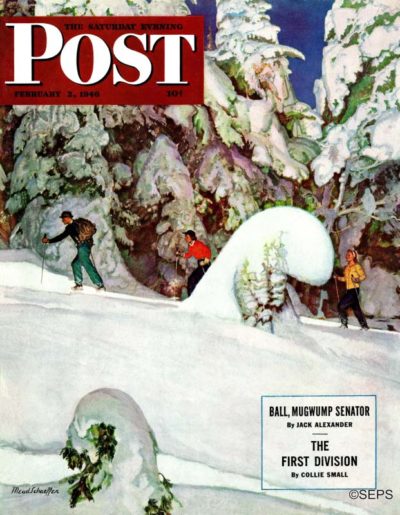

Mead Schaeffer

February 2, 1946

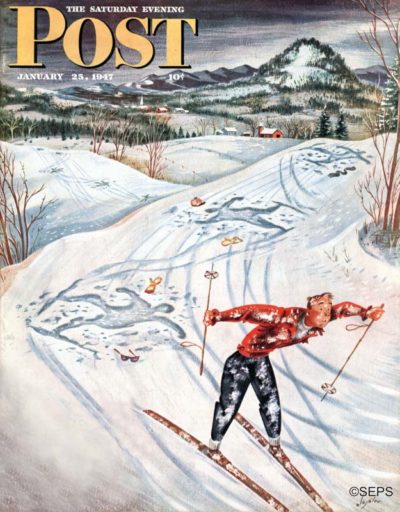

Constantin Alajalov

January 25, 1947

Norman Rockwell

January 24, 1948

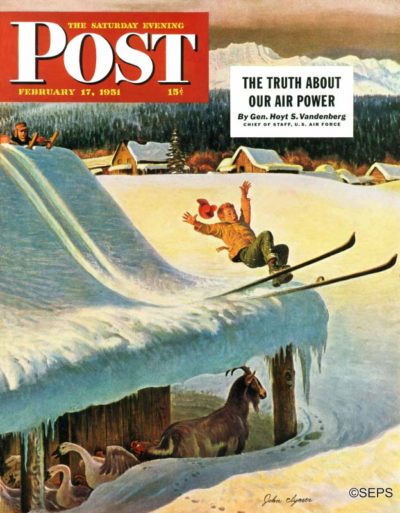

John Clymer

February 17, 1951

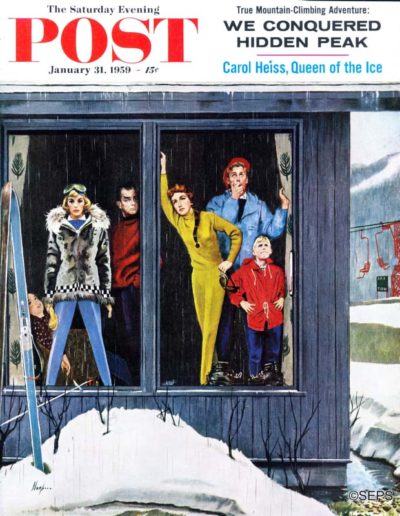

George Hughes

January 31, 1959

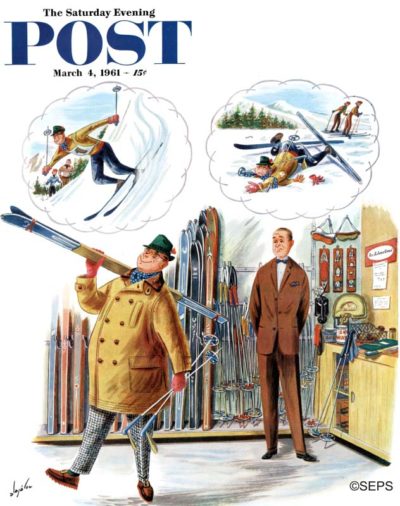

Constantin Alajalov

March 4, 1961

Cover Gallery: World War II

During World War II, the covers of The Saturday Evening Post illustrated many facets of the war, from the grit of battle to lighter moments on the home front. Many of the Post’s illustrators, including Norman Rockwell, Mead Schaeffer, and Constantin Alajalov, were there to evoke the most poignant and pleasing moments.

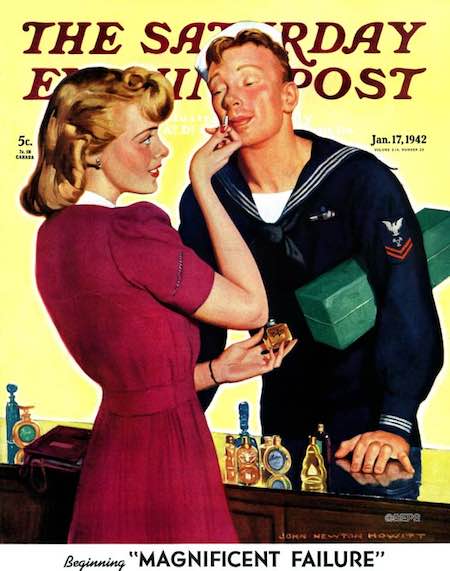

John Newton Howitt

January 17, 1942

America had just entered the war, passions still blazing from the attack on Pearl Harbor. It seems that other passions were blazing as well.

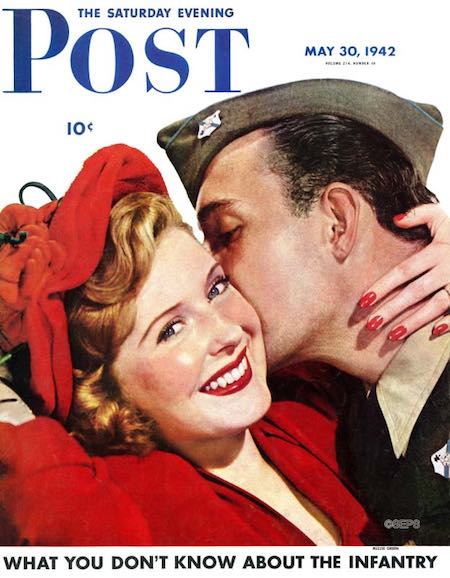

Ruzzie Green

May 30, 1942

This photograph by Ruzzie Green suggests that every soldier could come home to a gorgeous woman in red. The truth may not have been so glamourous, but it was still early in the war. Spirits – and hopes – ran high.

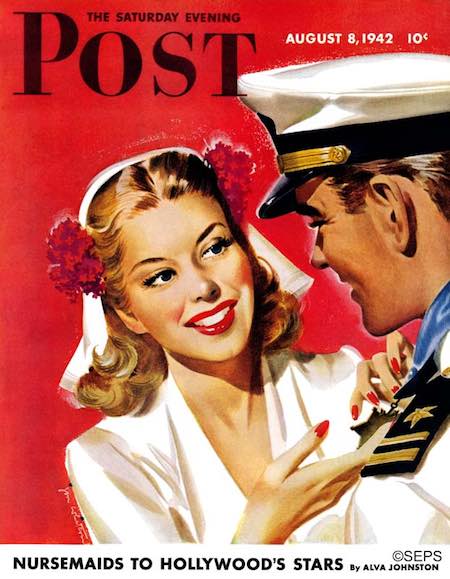

Jon Whitcomb

August 8, 1942

Illustrator Jon Whitcomb was a Lieutenant in the Navy during World War II, so he knew a thing or two about war, and the spoils therein. In addition to having a knack for illustrating beautiful women, he also served as a combat artist (who knew there was such a post?) in the South Pacific.

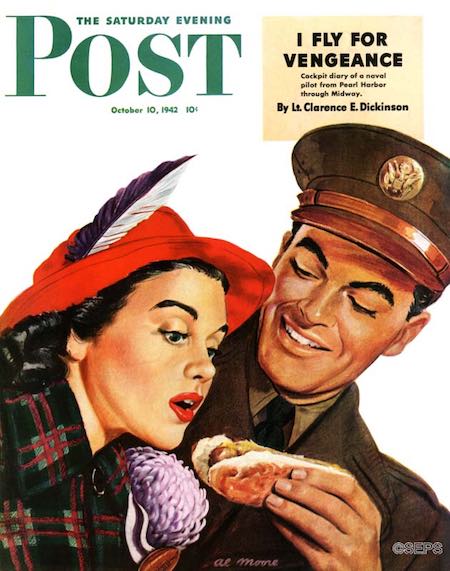

Al Moore

October 10, 1942

He thinks he’s being chivalrous, but she looks like she just spotted a worm on that wiener. Will she still take a bite?

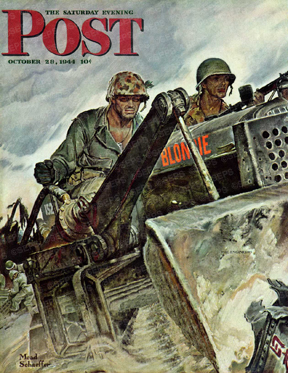

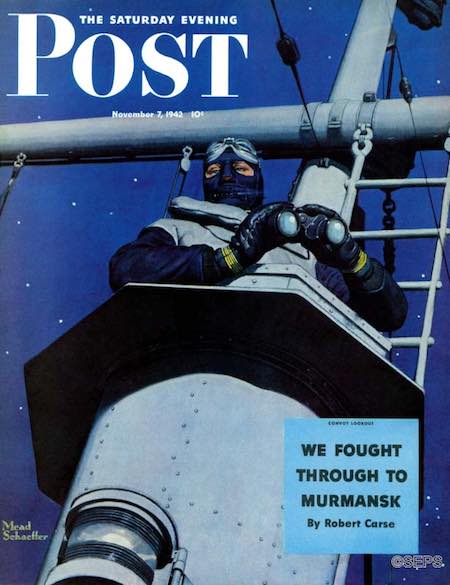

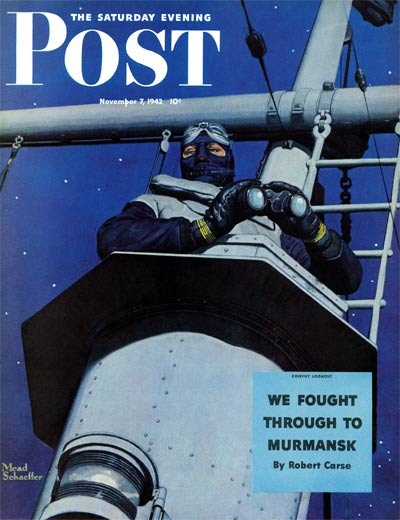

Mead Schaeffer

November 7, 1942

The Post’s war covers turned a bit more serious at the end of 1942, as American’s involvement approached the one-year mark. 1942 marked the beginning of a prolific period for artist Mead Schaeffer, who Illustrated 46 covers for the magazine.

George Garland

March 13, 1943

While women were not on the front lines in World War II, they played many critical roles, including volunteering with the Red Cross. The women (and men) of the Red Cross made enormous contributions during the war, both at home and overseas.

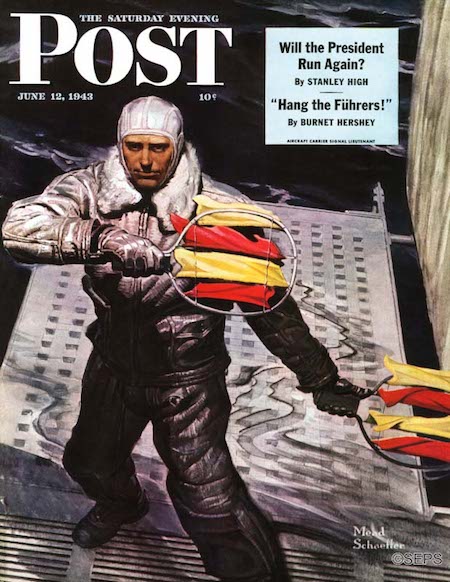

Mead Schaeffer

June 12, 1943

Early in his career, Mead Schaeffer created illustrations for Moby Dick and Les Miserables, so he was not unfamiliar with water or war.

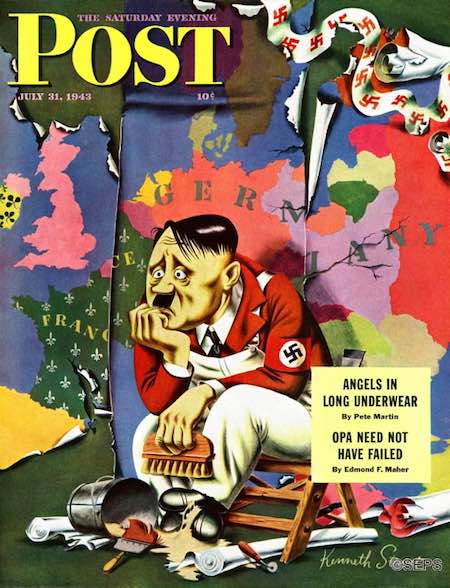

Ken Stuart

July 31, 1943

Prior to joining The Saturday Evening Post in 1943 as the art editor, Ken Stuart was an illustrator for the magazine, poking equal fun at Hitler, chickens, and children.

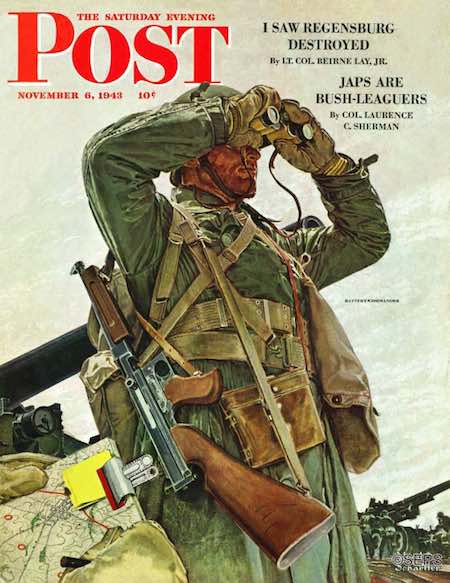

Mead Schaeffer

November 6, 1943

Mead Schaeffer often portrayed soldiers as ever-vigilant, as with this tank patrolman with his binoculars at the ready and his trusty Tommy gun by his side.

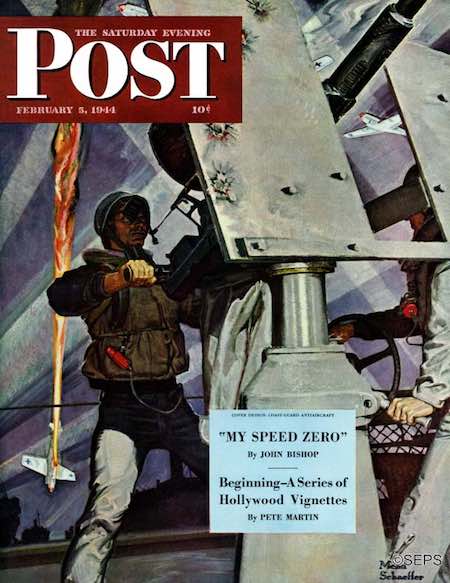

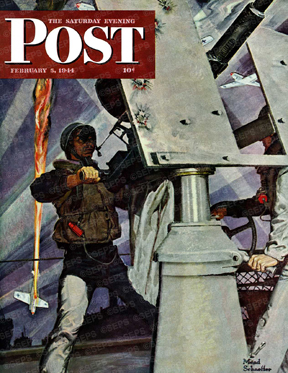

Mead Schaeffer

February 5, 1944

This soldier mans his anti-aircraft gun, with the evidence of his handiwork making a fiery red streak behind him.

Norman Rockwell

July 1, 1944

Norman Rockwell captures the emotions of a wounded veteran returning home.

Howard Scott

October 14, 1944

The war might be over, but this young man is ready for any enemies that might come his way.

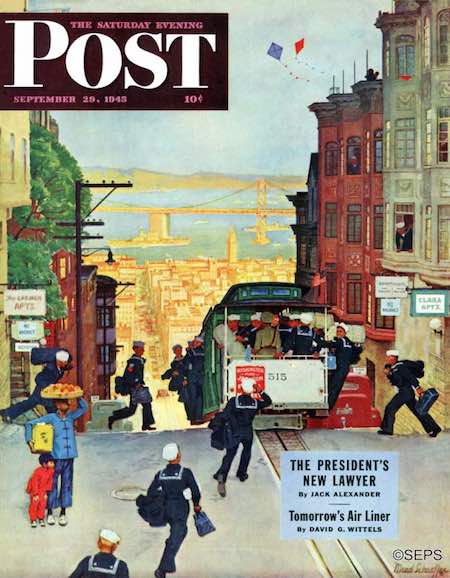

Mead Schaeffer

September 29, 1945

The war behind them, these servicemen are heading out for a night on the town in San Francisco.

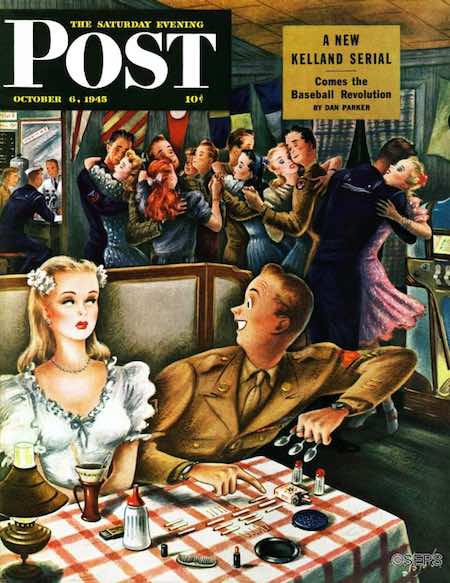

Constantin Alajalov

October 6, 1945

It looks like someone would rather be dancing.

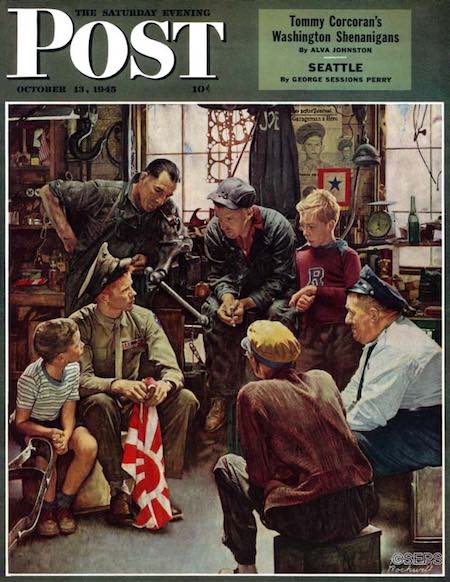

Norman Rockwell

October 13, 1945

A soldier’s friends and family sit, rapt, while the young man recounts tales of overseas adventures.

Mead Schaeffer

The child who sets out to be a career artist and skips the “starving artist” phase has a rare story indeed. But Mead Schaeffer’s ability was undeniable, his talents easily promoted. Born July 15th, 1898 to Presbyterian pastor Charles and his wife, Minnie, Mead grew up knowing he wanted a career in art. His work brought fame and fortune alongside a lifelong friendship with another American master, Norman Rockwell.

Born in Freedom Plains, New York, the Schaeffer family moved to Springfield, Massachusetts when Mead was a little boy. He graduated high school in 1917, and moved to Brooklyn, New York shortly after to attend the Pratt Institute.

At the Pratt Institute, Schaeffer studied under Harvey Dunn and Charles Chapman. His two mentors had started their own school, the Leonis School of Illustration, in 1915. The school’s philosophy followed that of their own teacher, the famed instructor Howard Pyle. Experiencing various art groups in the city, Schaeffer became acquainted with Dean Cornwell. Mead’s relationship with Cornwell led to Schaeffer’s first jobs producing illustrations for smaller magazines and publications. He graduated at the top of his class, already a working artist, in 1920.

Throughout Mead Schaeffer’s 20s, he worked for Dodd, Mead & Company, a publishing house for classic literature. Schaeffer provided illustrations for sixteen prominent works including The Count of Monte Cristo, Les Miserables, Typee, and Moby Dick.

On September 17th, 1921, Schaeffer married his wife, Elizabeth. They had two daughters, Consolle and Patricia. New York City soon became too cramped for the family. They moved to Rye, NY and then the artists’ colony at New Rochelle, NY where the artist first met Norman Rockwell. He later moved to Arlington, Vermont where he kept a studio in an old barn as Rockwell’s next-door neighbor.

Mead Schaeffer

February 5, 1944

Schaeffer was introduced to Saturday Evening Post editor Ben Hibbs through Rockwell. Schaeffer’s relationship with the Post resulted in a career spanning thirty years and 46 cover illustrations. Schaeffer became most famous for chronicling the military with authenticity.

Rockwell and Schaeffer set out to pitch an idea to the government about ads for war bonds, but they were rejected. Hibbs picked up the idea and sponsored their work through The Saturday Evening Post. Schaeffer spent 1942 to 1944 as a war correspondent. He flew in planes, rode in submarines, and toured with soldiers to get a feel for the soldiers’ experiences in World War II. His collection, including 16 Saturday Evening Post covers, went on a tour to 92 cities in the United States and Canada. The tour’s purpose was to drum up sales for war bonds.

After the war, in the summer and fall of 1947, the Schaeffers and the Rockwells took a two and a half month family vacation to the American West. The families were so close many works by both artists contain the other’s children as models. Schaeffer’s wife often took dozens of photographs from all angles while the artist studied the scene. After the trip, the artist studied his wife’s photographs and incorporated their view into his work. From all of his sketches and studies, the trip provided only six Post covers.

Over the course of a 30-year career, Schaeffer provided 5,000 illustrations to books, magazines, and advertisements. His last cover for the Post was December 26th, 1953. He spent much of his retirement sketching and fly-fishing, often taking trips to Puerto Rico. By the end of his career, Schaeffer had worked for The American, Good Housekeeping, Cosmopolitan, Scribners, Home Companion, Ladie’s Home Journal, Redbook, McCall’s, St. Nichol’s Century Magazine, and of course, The Saturday Evening Post.

He died of a heart attack on November 6th, 1980 while at lunch with his contemporaries at the Society of Illustrators in Manhattan. Today his works are on display at the USAA in San Antonio, Texas.

Covers by Mead Schaeffer

Corp of Engineers

Mead Schaeffer

October 28, 1944

San Francisco Cable Car

Mead Schaeffer

September 29, 1945

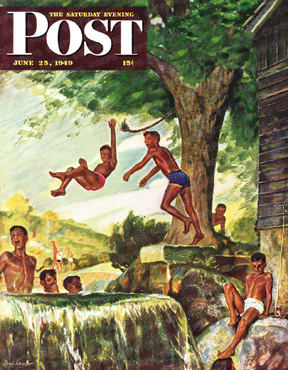

Swimming Hole

Mead Schaeffer

June 25, 1949

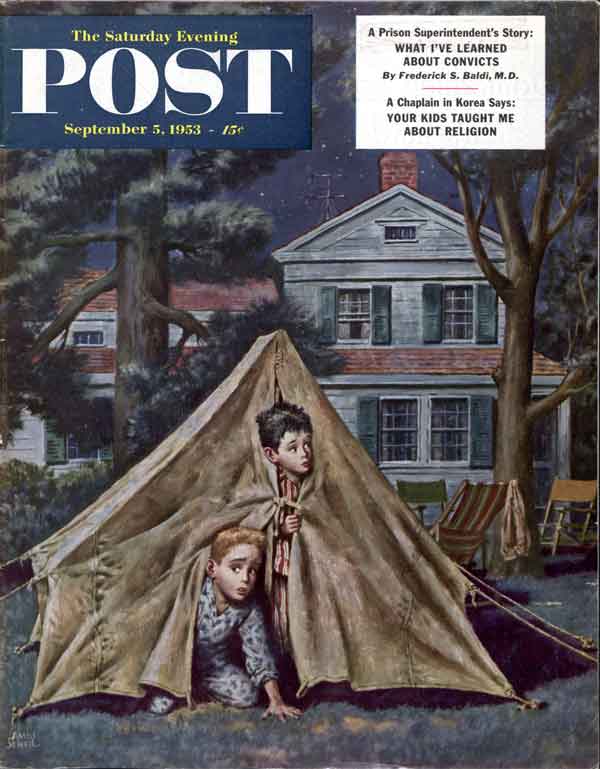

Beyond The Canvas: Camping and the American Experience

Amos Sewell

September 5, 1953 © SEPS

From cowboys to boy scouts, camping has long been an adventure for all ages. We camp to sightsee in national parks, play in the backyard, cattle drive across the plains, or vacation for fresh air.

For the last hundred years, The Saturday Evening Post has shown many ways in which Americans enjoy the outdoors.

Starting with Amos Sewell’s September 5, 1953 cover, Backyard Campers, two frightened little boys attempt to be tough enough to camp out all by themselves–even if aloneness means the isolation of being the only tent in a fenced-in, suburban yard just steps from the safety of their home.

Still, the little lawn campers are spooked by the foreignness of their own backyard in the darkness. If they get too frightened, they reason, they’ll plan a mad dash to the safety of the house, with warm beds and glowing nightlights for comfort. A rite of passage accomplished, if short-lived.

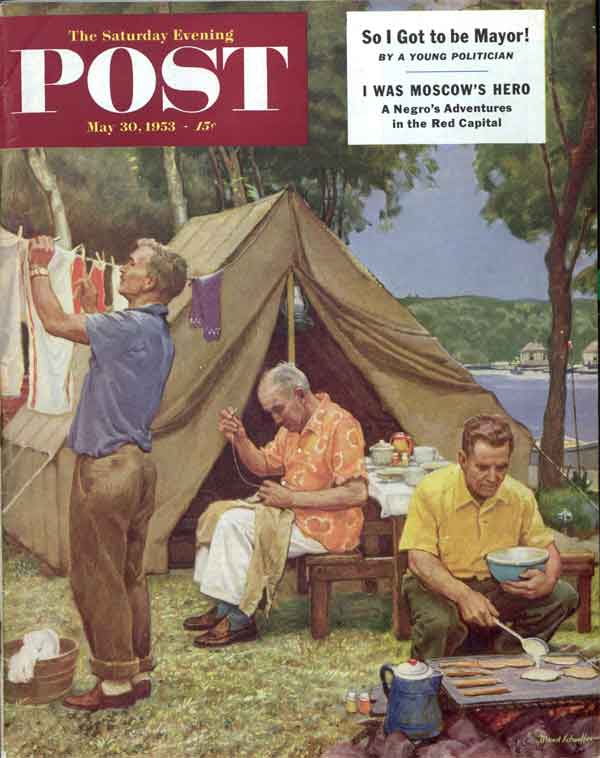

But camping isn’t just a backyard activity for little boys. As Mead Schaeffer shows, it’s a multi-generational bonding experience. His May 30, 1953 cover, Three Generations Camping, provides a more relaxed setting focused on socialization through outdoor enjoyment. The camping tradition turns boys still afraid of the dark into nature-tested outdoorsmen. In Schaeffer’s illustration, we see a whole family tending to their assigned tasks while a communal breakfast cooks over the griddle.

Mead Schaeffer

May 30, 1953 © SEPS

Speaking of campfire food, mealtime around an open fire is almost as much a right of passage as the act of camping itself. What’s a campout without a bonfire, after all? And what’s a bonfire without campfire food?

Flapjacks by J.F. Kernan, from the November 10, 1934 issue, shows a camper who’s preparing a fresh stack of pancakes over the fire. Meals are the best time for campers to rest from a day of hiking, fishing, trail riding, and general physical exertion. It’s a time to take the boots off, socialize with peers, enjoy the surroundings, and most importantly, replenish lost calories.

These three Post covers idealize the innocent notions of nighttime fears, the happiness of cooking over a fire, and the communal experience of enjoying the outdoors. However, unforeseen circumstance can cause immense frustration that is a far cry from the glossy memories of a good campout. The difficulty of correctly pitching a tent is a familiar, well-worn joke in our culture, as Thornton Utz shows us in Making Camp, from the July 19, 1958 issue. What a maddening mess!

Camping is integral in the American experience, and arguably the least expensive right of passage in this country. Even before smartphones and computers, people felt the need to escape the city and head for the hills, to breathe fresh air, experience wildlife up close, and live a little simply (if uncomfortably) even if just for a weekend. Along the way, The Saturday Evening Post has shared our nation’s appreciation for this truly American experience.

Thornton Utz

July 19, 1958 © SEPS

Mead Schaeffer

May 30, 1953 © SEPS

Amos Sewell

September 5, 1953 © SEPS

J.F. Kernan

November 10, 1934 © SEPS

Classic Covers: Mead Schaeffer

from September 14, 1946

Mead Schaeffer painted 46 covers for The Saturday Evening Post, and behind them often lurked intriguing tales.

A writer accompanied artist Mead Schaeffer out West in 1946 and found that “making one of these covers is a fairly complicated project, not unlike the shooting of a movie.”

“The LX ranch, near Amarillo”, Post writer Lewis Nordyke wrote, “covers some 75,000 unplowed acres, and has been used as a cattle range since the days of the Plains Indian, with never a complaint from the cattle.”

But when cover artist Mead Schaeffer set out to paint a chuckwagon scene, he “took a thoughtful look at the range and said it wouldn’t do for his purposes. The trouble with the range, he said, is that it didn’t look like a range.”

This puzzled “Dad” Robinson, who had been the ranch cook for almost sixty years. “If this don’t look like range, I’d sure like to know what range looks like.” The artist explained that sometimes “the real thing isn’t always paintable.” Schaeffer continued, “But it doesn’t matter. We can roll out the chuckwagon…and pick up the range somewhere else.” That’s the illustration business.

“His business,” the old cook was overheard to say, “Must be durned peculiar.”

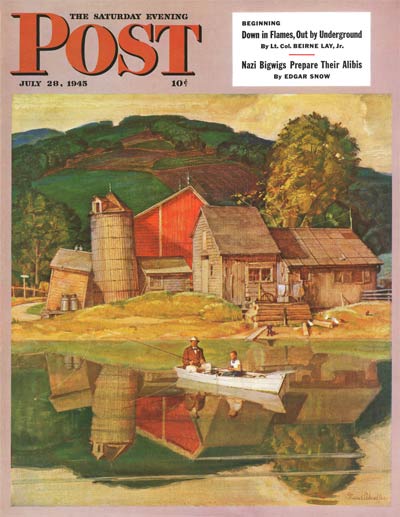

from July 28, 1945

In the mid-1940s, Post editors were running a series of covers as a sort of regional album of America, and readers never knew what part of this nation’s majesty they might view next.

Often the artist would have to do a cover months in advance, painting, say, a Christmas cover in June.

But this time, Schaeffer told editors, in August, “I started out for a day’s fishing on Schoolhouse Pond (Cambridge, New York), telling myself I would concentrate on my next assignment, a New Year’s Eve cover, as I cast for bullheads. The lure of a drowsy summer day did the rest,” and he painted this summer cover…in summer!

Post editors once described Mead Schaeffer as a fisherman who happened to also paint. The artist/outdoorsman was so enamored of the sport he moved from New York to Vermont after meeting Norman Rockwell, as this story by Holly Miller in a 1979 issue states:

from May 19, 1951

“I had no intention of moving from New Rochelle,” explains Schaeffer. “But when Norman and I finally met at that party, he mentioned he had just bought some property on the Batten Kill River in Vermont. I said, ‘You mean you’ve got a place on the greatest fishing river in New England?’ We went up before he even installed the heat.”

“Just before this picture was painted,” Post editors wrote of this 1951 cover (left), “the man was calmly trying to feed the trout another variety of fly and they were calmly ignoring his hospitality.

Suddenly, a countless family of Green Drake ‘nymphs,’ which previously had risen to the surface of the water to hatch, discovered that they had wings, and decided to zoom into the wild blue yonder.”

And to drive fish and fisherman alike crazy. The angler is attempting to tie an artificial Green Drake to his line.

Rockwell and Schaeffer became neighbors and close friends. They shared models. Rockwell’s sons would show up in Schaeffer paintings, and Schaeffer’s daughters in Rockwell’s.

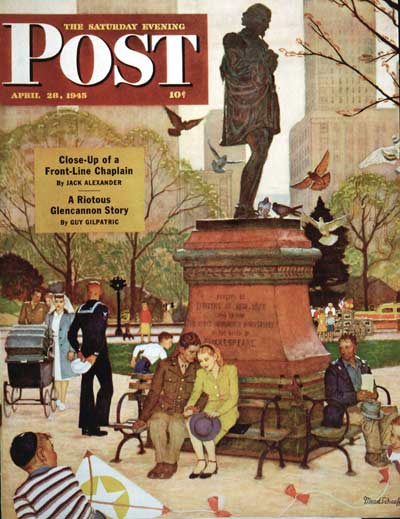

from April 28, 1945

The two families even traveled together, and Rockwell accompanied Schaeffer on many fishing trips. As he would be the first to admit, however, Rockwell was not much of an outdoorsman. Even though they fished together, Schaeffer joked: “Norman was lousy at it.”

Speaking of Schaeffer’s daughters, they appear in this painting. One is the young lady being romanced under the statue of Shakespeare and one is a nearby nurse. Schaeffer had to paint the Central Park scene twice.

Editors noted: “The first attempt, made in the thirty-two degrees below zero weather of Vermont, was ruined when the white-lead sizing used to prime the canvas froze and the paint flaked off.”

Would you believe the heavens once had to be scrambled for a Post cover?

from November 7, 1942

Schaeffer painted a gritty and realistic series of covers during WWII. The Navy found the first version of this cover a bit too realistic and asked the artist not to use it.

They felt the enemy might be able to calculate the Russian convoy route from the formation of the stars. The artist felt he owed it to the fighting men to strive for authenticity, but promptly reshuffled the constellations.

The Navy supplied the equipment and model depicted for this view of the crow’s nest of a PC boat. To get the personal feel of the scene, Schaeffer had a long talk at the New York Navy Yard with seamen who had stood the watch.

“The time of night portrayed,” the artist noted, “is the most dangerous and vulnerable in which to operate, as it is clear and starlit and the ships form silhouettes, making them perfect targets.”

from August 25, 1945

As in the case of the “Farm Pond Landscape,” this scene was meant to be a vacation for the artist. But it turned into another busman’s holiday. While in California, Schaeffer drove out to Lone Pine to see unusual rock formations.

He was quite content to admire this strange rock when darned if a buckboard didn’t come rolling around the bend. Perched aboard were a man, a woman, and a sailor. The sailor especially caught his eye.

“He was a big, rawboned youngster, obviously built for the saddle instead of a uniform.”

Thus, wrote Post editors of this 1945 painting, “Schaeffer’s breathing spell evaporated and he began to make sketches for another Post cover too good to pass up.”

Classic Covers: Lighthouses

Why are we so fascinated by lighthouses? Is it because they are so picturesque? Or because, if they could talk, what exciting and harrowing tales of the sea they could tell? Whatever the reason, two Post cover artists — Mead Schaeffer and Stevan Dohanos — loved them as much as the rest of us.

Lighthouses by Stevan Dohanos

Lighthouse Keeper

by Stevan Dohanos

June 26, 1954

“Here a Coast Guard man,” Post editors wrote in 1954 of the cover above, “is adding to his duties the task of guarding coastal waters against getting too crowded with fish.” The ever-ravenous gulls await whatever tidbits they can make off with. The lighthouse was unidentified.

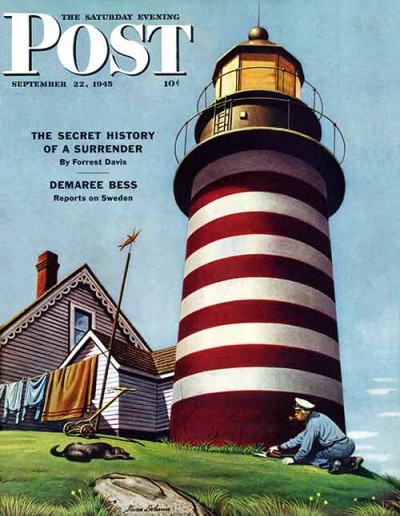

The candy striped tower (below) oversees a strait between the United States and Canada called Quoddy Narrows, looks much the same today as when Stevan Dohanos painted it in 1945.

The West Quoddy Light Keepers Association website fills us in on the intriguing history of this structure: The first tower, which was made of wood, “was built in 1808, by order of President Thomas Jefferson. The tower standing and operating today was built in 1857 and became operational in 1858.”

Lighthouse Keeper

by Stevan Dohanos

September 22, 1945

How did they illuminate the lighthouse in those days? The Light Keepers Association tells us it was “originally oil from sperm whales; to lard oil in the 1860s, to kerosene about 1880; to electricity in 1932.”

The artist took, well, artistic license, in painting this scene. Although the lighthouse was in Lubec, Maine, the lighthouse keeper trimming the grass was at Sankaty Light in Nantucket. Dohanos had made sketches of the striped West Quoddy lighthouse the year before, and because it was closer, went to the Sankaty Lighthouse to refresh his memory of the details. Turns out the Nantucket folks didn’t have much information on the Maine lighthouse. However, “they were cutting the grass at Sankaty Light,” editors noted, “and Dohanos liked that touch of domesticity or agriculture or whatever it is, so he included it.”

Mead Schaeffer’s Lighthouses

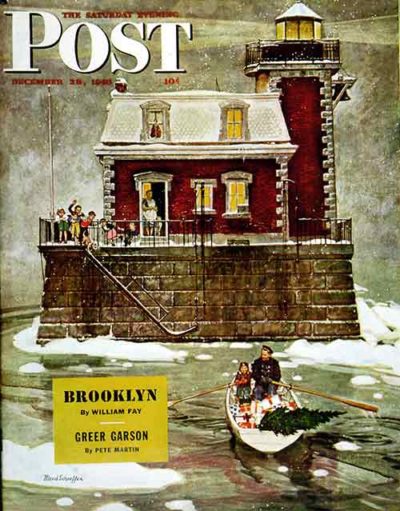

Christmas at the Lighthouse

Mead Schaeffer

December 28, 1946

Instead of resting on a strip of coastal land, this charming structure sits in the Hudson River between a town of the same name and Athens, on the other side. A large mud flat in the river stranded unsuspecting ships, so in 1873, construction began on the Hudson-Athens Lighthouse.

Today the lighthouse (at right) is an active aid to commercial ships and private boats in the Hudson River as it has been since 1874. (Photo courtesy of Hudson-Athens Lighthouse Preservation Society.)

The website for the Hudson-Athens Lighthouse Preservation Society includes floorplans and the history of the structure and its keepers. One of those, “Emil J. Brunner, kept the light from 1930 to 1949.” When Post cover artist Mead Schaeffer wanted to paint the scene, he asked Brunner and his family to pose.

“Artistic license allows for a dog (at the top of the steps),” writes Louise Bliss of the Preservation Society, “which was of course against Coast Guard rules, and there are too many children and there were no electric lights.” She’s right, the keeper and his wife had five children; the artist generously granted them eight. Intriguingly, Bliss noted, one of the little girls depicted, now grown of course, “comes to public tours in the summer and tells the tales of living on the lighthouse.”

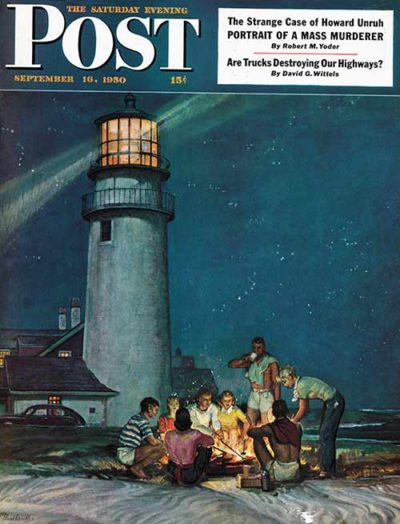

“Beach Bonfire”

by Mead Schaeffer

September 16, 1950

The cozy September scene (above) from 1950 is in Cape Cod, but there are perhaps 15 or so lighthouses on the Cape and the specific one was not identified. Perhaps a knowledgeable reader can let us know?

Classic Covers: World War II

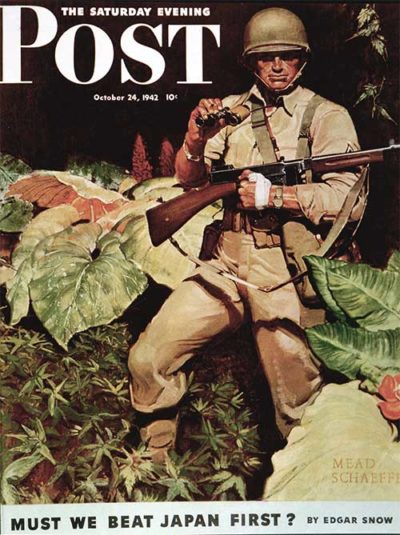

“Jungle Commando” by Mead Schaeffer

“Jungle Commando”

by Mead Schaeffer

From October 14, 1942

The great artist Mead Schaeffer (1898-1980) worked as a war correspondent for The Saturday Evening Post, depicting in cover after cover the daily life of the military man. Schaeffer worked hard for authenticity: he hitched a ride on a submarine, a Coast Guard patrol boat, and various aircraft for his over sixteen World War II covers.

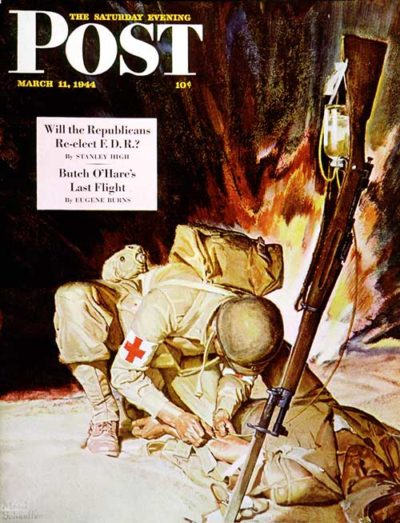

“Medic Treating Injured in Field” by Mead Schaeffer

“Medic Treating Injured in Field”

by Mead Schaeffer

March 11, 1944

This 1944 illustration, again by Schaeffer, is a striking reminder of the role of the brave medic in the midst of battle. Schaeffer felt honor-bound to depict the real world of the soldier. But a cover from later that same year, which we show below, depicts a more relaxed side.

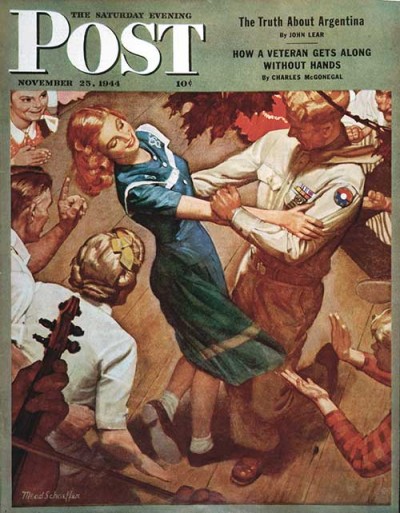

“Barn Dance” by Mead Schaeffer

“Barn Dance”

by Mead Schaeffer

November 25, 1944

A well-deserved break at a barn dance is the only war cover Schaeffer did showing a fun side of the times.

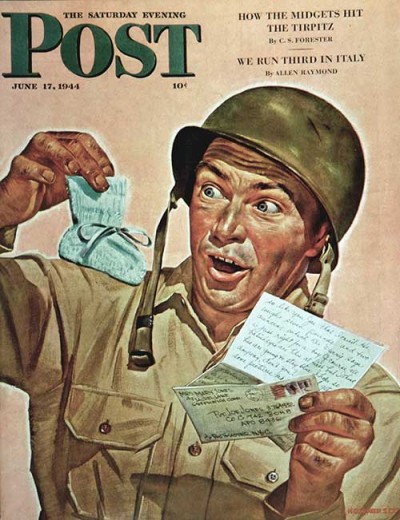

“Baby Booties at Boot Camp” by Howard Scott

“Baby Booties at Boot Camp”

by Howard Scott

June 17, 1944

Artist Howard Scott also did a number of covers during World War II—usually of the lighter side. A cover bound to make you go “awww,” the story here is clear: It’s a boy!

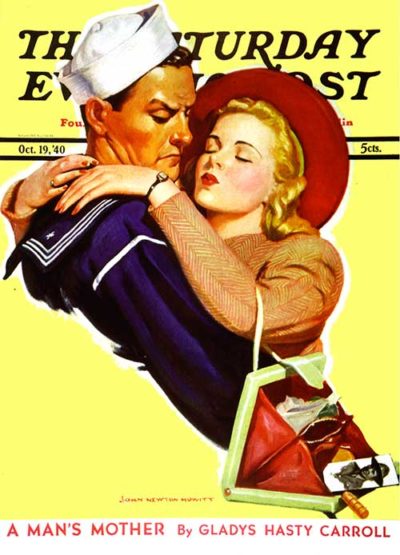

“Soldier or Sailor” by John Newton Howitt

“Soldier or Sailor”

by John Newton Howitt

October 19, 1940

This 1940 cover by artist John Newton Howitt shows a twist on the old saw about a sailor having a gal in every port. Tumbling from the lady’s purse is a photo of a soldier. Wartime is hell, buddy.

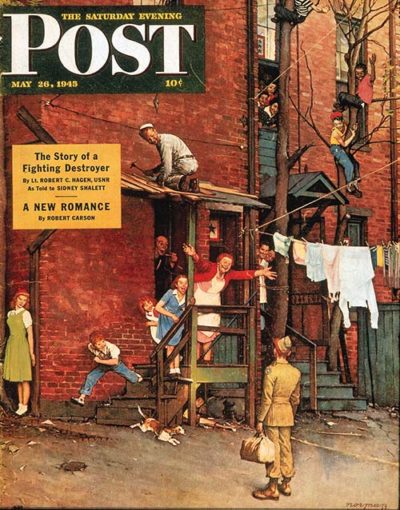

“The Homecoming G.I.” by Norman Rockwell

“The Homecoming G.I.”

by Norman Rockwell

May 25, 1945

“It was of course very gratifying for me when this painting was selected by the U.S. Treasury for the official poster of the Eighth War Bond Drive,” said Norman Rockwell. The family is rushing out to greet the returning soldier, including the dog and … could mother’s arms be open any wider? The whole neighborhood is delighted in the scene. Notice the shy girl next door waiting patiently to see her sweetheart. You can click on the cover for a close-up of this classic.

For more Rockwell WWII covers, see: “The All-American Soldier: Willie Gillis” and “Thanks Robert Buck, Good-bye Willie Gillis.”

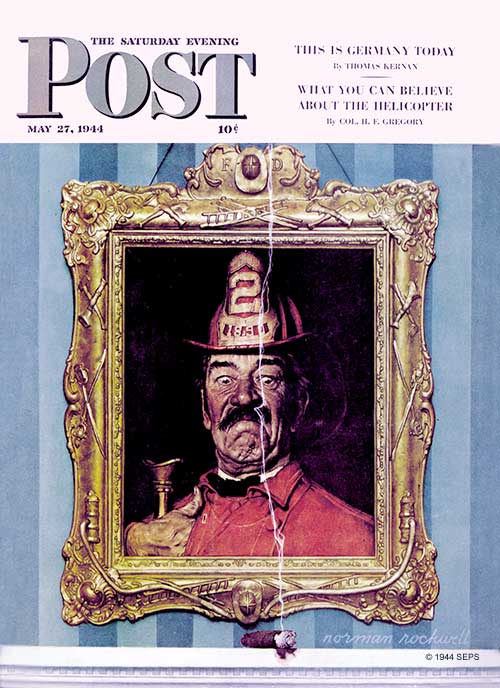

Rockwell’s Silly Side

What happens when a fireman (even in a painting) smells smoke or plumbers are turned loose in a fancy boudoir? Our favorite artist has the answers.

“The Fireman”

This may be the only known time when a picture frame inspired the painting that went into it. Rockwell found this unique frame while browsing through a junk store. Well, if you have an empty frame, you have to fill it, right? Carved into the old find were some artifacts of the fire-fighting profession: axes, ladders, and so on. It practically begged for an old-fashioned fireman to occupy it. So the artist conjured up this gent in the turn-of-the-century uniform, complete with a big, bushy mustache. In a fit of pure goofiness, he added a stiffly disapproving glare and displayed a lit cigar beneath the painting for picture-within-picture fun.

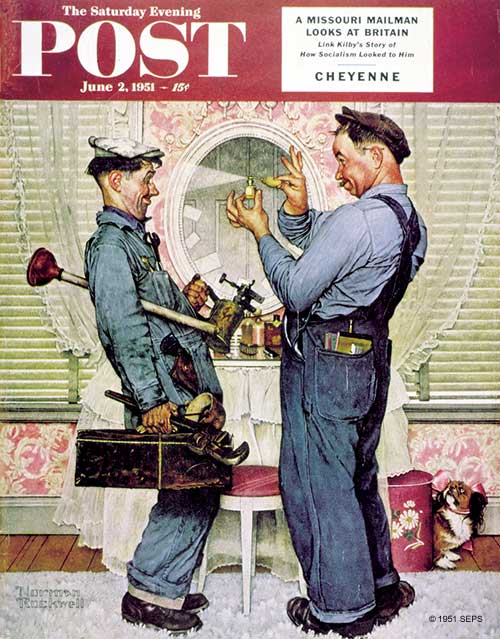

“The Plumbers”

For pure silliness, you can’t beat “The Plumbers” from 1951. Who but Rockwell would come up with a couple of working stiffs in a fancy boudoir? The homeowner is out for the day, but not the indignant, pink-bowed Pekingese. While crawling under dank sinks and unclogging who-knows-what is all well and good, why not have a little fun? “Here, Clyde, let me make you smell pretty!”

As usual, the details are terrific: look at that wallpaper, the grubby coveralls, and the plumbers’ tools (you can click on the cover for a closer view). These guys were actual plumber acquaintances of the artist, and they were asked to bring along their gear. Who else would have friends who looked like Laurel and Hardy?

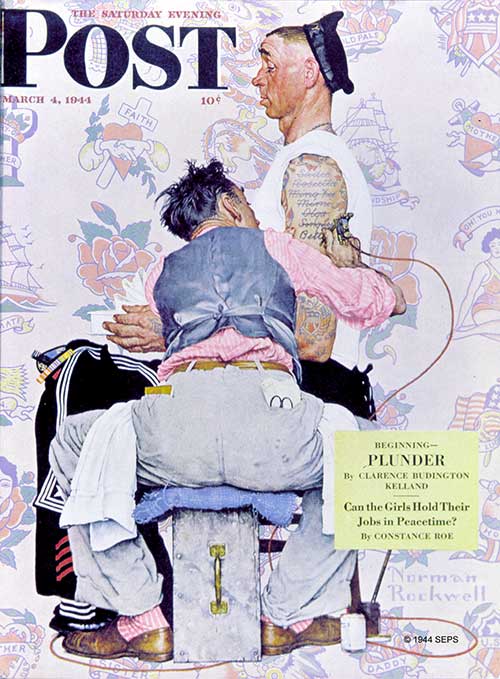

“Tattoo Artist”

During the WWII years, there were many, many serious Post covers with soldiers. If you look up artist Mead Schaeffer at Curtis Publishing, you’ll see armed paratroopers, jungle commandos, and military personnel in a myriad of war activities. Oh, speaking of Mead Schaeffer, he was a buddy of Rockwell’s and posed for this painting as the tattoo artist. He staunchly maintained that Rockwell made his posterior larger than in real life, which Rockwell denied. By the way, Mr. Schaeffer, I dig those socks. Apparently, the issue remains unresolved to this day. The sailor in the painting had apparently been in many ports, but Rosietta, Olga, and the rest are ancient history. This is a new port, and there is a new love-of-his-life. Rockwell even used a sheet of available tattoos as the background.

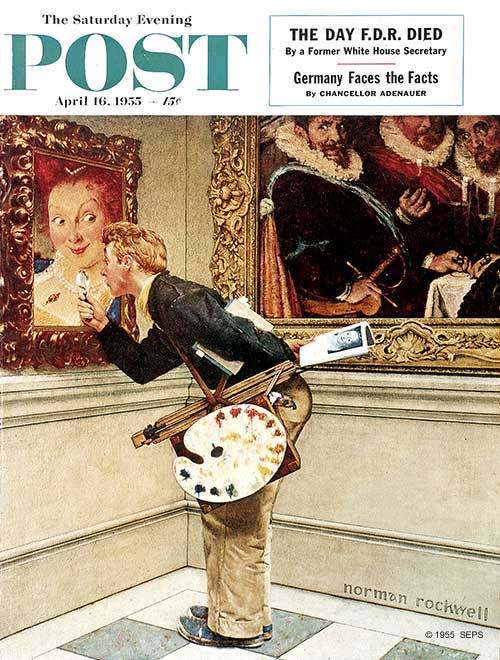

“The Critic”

The young art student is studying a painting that is studying him—an “unstill life,” if you will. Except for the frowning Dutch masters in the other painting, it is all in the family. The art critic studying a locket in the painting is Jerry Rockwell, the oldest son of the artist. The whimsical lady in the painting is his mother, Mary (Rockwell added flaming red hair for fun). Should the student notice the painting looking back at him or look over his shoulder to see the Dutch gents glaring at him, I suspect he would run screaming from the museum and take up another subject to study.

Classic Covers: By the Light …

… of the silvery moon? of a sparkling Christmas tree? of a glowing Jack-o’-lantern? The “star” in some paintings is not just the subject of the piece, but the lighting—a face lit by lamplight, a city bathed in sunshine, or the reflections of a snowfall. Post cover artists show intriguing use of light in all seasons—outdoors and some interesting, or even creepy, indoor lighting.

San Francisco is the city with the sunbathed background in the September 29, 1945, cover by artist Mead Schaeffer. Frisco was a jumping-off place during the war, and the sailors in the cover are all jumping onto a streetcar heading toward the Golden Gate Bridge. The angle of the sunlight and shadow is intriguing;

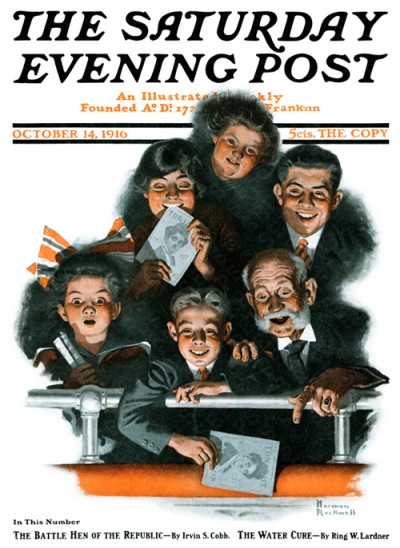

A good buddy of artist Schaeffer, a guy named Rockwell, knew a thing or two about lighting, and one of our favorite examples is from 1916. The whole family is watching a movie—notice the Chaplin programs. Rockwell, as we’ve said before, is all about faces, and their expressions are magical, enhanced by theater lighting.

One of the loveliest examples of lighting we found was the luminous glow of a Jack-o’-lantern in artist Pearl L. Hill’s November 1, 1924, cover. It’s hard to steal the scene from a pretty girl in a party dress, but the mean ol’ carved pumpkin is almost doing just that.

The light casts eerie shadows in J.C. Leyendecker’s December 1, 1934, cover. We doubt the cook in this cover planned it this way, but she couldn’t have picked scarier lighting for her spooky story. She seems like a good storyteller, but let’s hope the little boy (and cat) doesn’t have nightmares.

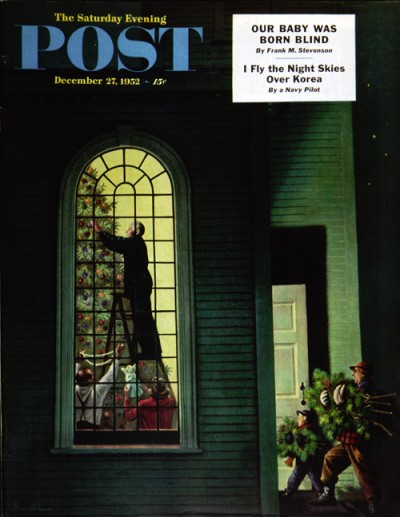

We love the way cover artist Stevan Dohanos plays with light in his holiday cover from 1952. We have a voyeuristic view into a church where the Christmas tree is being decorated, and just enough light is spilling from the door to show us the hardworking man and boy bringing in armloads of pine boughs. Love the too-tall Christmas tree, but we have to say lighting is the star of this one.

Gallery

Mead Schaeffer

September 29, 1945

Norman Rockwell

October 14, 1916

Pearl L. Hill

November 1, 1924

J. C. Leyendecker

December 1, 1934

Stevan Dohanos

December 27, 1952