Remembering the Fallen of World War II

One of the most searing scenes of the 75th Anniversary of D-Day ceremonies last year was at the Normandy American Cemetery on the bluff overlooking Omaha Beach. Beautiful in its way, the grass in the 172.5 acres so green it might be in a Technicolor movie, the chalk white crosses and Stars of David on the graves — more than 9,380 — lined up in a symmetry that is breathtaking.

Beneath each cross and star lies a fallen serviceman, a G.I. we honor — every day, I hope, but especially on Memorial Day, the day set aside each year to remember the fallen. Rightly so, as the inscription on one marker puts it:

Into the great mosaic of victory

This priceless jewel was set.

So, too, the fallen in the Luxembourg American and Memorial Cemetery — 50.5 acres in Luxembourg, with 5,076 graves — one of the white crosses there marking the final resting place of General George S. Patton, “Old Blood and Guts.” He led his Third Armored Division 100 miles on icy roads in bitter cold weather in December 1944 to break the German encirclement of Bastogne in The Battle of the Bulge.

The deadliest U.S. battle of World War II, fought when the war in Europe was supposed to be over.

The surprise German attack had just started the day I approached the entrance to the Chicago Daily News Building on December 18, 1944, in hopes of getting a job as a copygirl at the Chicago Daily News. The Allied retreats each day, before the eventual advances, made up the headlines my first weeks there. Newspapers were all around me, editions delivered by copyboys coming up from the press room with the latest edition every couple of hours, distributing them to the various news desks and editors. Big black headlines were followed by stories with the details, notably the siege of Bastogne, which the Germans surrounded early on in the fighting.

Because the German attack pushed a long, deep curve in the Allied lines before the tide turned, it came to be known as The Battle of the Bulge. The daily battles, artillery shellings, and tank attacks left those rows of white markers in the Luxembourg American and Memorial Cemetery.

The war in the Pacific was equally costly.

It came into my life the morning of February 1. When I came to work I was told not to report to my usual post at the city desk but to go to a far corner of the city room, a square of four empty desks. On the cleared top was a stack of copy paper, a pair of scissors, a glue pot, and a streamer of Associated Press (AP) copy.

The streamer was not a story but a list of names of the men the Allies had just rescued from a Japanese P.O.W. camp in the Philippines — a military operation so dramatic, daring, and dangerous it came to be known as “The Great Raid.” A raid so dramatic, daring, and dangerous that John Wayne led the rescue mission in the 1945 film Back to Bataan. In a story in the late edition, AP put it this way:

SIXTH RANGER BATTALION CAMP, LUZON — (AP) — There is a long, dusty, twisting land near here which should become a war monument, for today it bridged two worlds. It leads across the plain toward the death camp where 513 prisoners of war were rescued by American Rangers and Filipino guerrillas.

To get the names of the rescued men out to their loved ones as quickly as possible, AP was listing them as they received them, not taking time to put them in alphabetical order. That was what I was to do.

I cut the names of the men apart, long narrow strips, and laid them out on the desk top. When a deadline approached, I reached for the glue pot and made a wide strip down the center of a sheet of copy paper, and stuck the names down. I remember that while they were secure, the glue did not reach the ends … and I can still see those ends curling up.

Copyboys would come for the list for the next edition and regularly bring me a new AP streamer with its list of names.

I finished just after lunch and settled in at my regular post at the city desk, ready to answer calls of “Copy!” and take stories to the copydesk or get clips from the library. And when things grew quiet late in the afternoon, I had time to read the latest edition, just dropped off at a nearby news desk.

Amongst all the happy photos of local families beaming at family pictures of their rescued sons or husbands, boyfriends or brothers, were the first stories about the men and the toll their years in the POW camp had taken.

There were those so weak, emaciated, a Ranger could carry two men on his back. Some limped from beriberi. The legs of some were scored by tropical ulcers and other diseases, and there were those who looked up helplessly from litters.

They talked in low tones of Japanese brutality and the Death March of Bataan, of the final terrifying week of bombing and bombardment that hit Corregidor, of men dying like flies, of disease, of ten hours daily in prison camps, under the hot sun in fields, or waist high in water of rice paddies under hard eyes, of frequent beatings and shootings.

They recalled when 10,000 men at the Cabanatuan prison camp used to spend all day strung out in line for a canteenful of water from one of the camp’s four spigots.

Now, they lined up for a supper of boned chicken, peas, beans, fruit salad, jam and cocoa — a veritable banquet after the starvation fare of the Japanese prison camp.

Invited to ask for more and eat all they want, one of the men said, “Where we come from they put you in the guardhouse if you asked for more.”

It was only with time that I realized each name on those AP streamers — soon a narrow slip of paper on the cleared top of the dark green metal desks — was the name of a man who had not only survived a Japanese POW camp but the Bataan Death March, one of the most horrific episodes of the war. So named because 10,000 of the 76,000 men who had surrendered when Bataan fell to the Japanese died during the five-day, forced march —66 miles in jungle heat to the Japanese prison camps. Some guards took the men’s canteens and emptied them of water so they would have nothing to drink. Others killed, bayoneted, and beat men who tried to get a drink from the gushing artesian wells they passed.

And so, while I don’t remember the names I alphabetized that day, I remember the men whose names were on those narrow slips of paper with the ends curling up — what they endured in their service to their country.

One of the survivors, Glenn Frazier, gave an account of the horrors in the Ken Burns documentary for PBS The War. It appears in the companion book, Frazier saying:

I saw men buried alive. When a guy was bayoneted or shot, lying in the road, and the convoys were coming along, I saw trucks that would just go out of their way to run over the guy in the middle of the road. And likewise the rest of the trucks, and by the time you have fifteen or twenty trucks run over you, you look like a smashed tomato. And I saw people who had their throats cuts because [the Japanese] would take their bayonets and stick them out through the corner of their trucks at night and it would just be high enough to cut their throats. And I saw men beaten with a rifle butt until there just was no more life in them. I saw Filipino women [who tried to bring us food or water] cut. Their stomachs were cut open. Their throats were cut. I saw Filipino and Americans beheaded just with one swipe of a saber.

An officer who’d been keeping track of the cut-off heads he saw as he passed stopped counting at twenty-seven lest he go mad.

Soon the headlines moved on again. This time, to Iwo Jima. The Marines landed there February 19.

The flag raising atop Mount Suribachi as they took control of part of the island would become one of the most famous pictures of World War II, or any war, for that matter. It would win the Pulitzer Prize for AP photographer Joe Rosenthal, go on to become a huge bronze statue — the centerpiece of the United States Marine Corps War Memorial in Arlington, Virginia — and an array of U.S. postage stamps through the years.

Many a headline reported the battle, the progress, the fierce resistance the Marines encountered, before the fighting ended March 26. But it was only when I read the book Flags of Our Fathers by James Bradley, son of one of the flag-raisers, that I fully appreciated what the Marines faced.

“The Marines fought in World War II for forty-three months,” Bradley said. “Yet in one month on Iwo Jima, one third of their total deaths occurred. They left behind the Pacific’s largest cemeteries: nearly 6,800 graves in all, mounds with their crosses and stars.”

Someone chiseled these words outside the cemetery on Iwo Jima:

When you go home

Tell them for us and say

For your tomorrow

We gave our today

Featured image: Marines raising the American flag on Iwo Jima, February 23, 1945 (photo by Joe Rosenthal / public domain)

Considering History: The Lessons of Memorial Day’s Decoration Day Origins

This series by American studies professor Ben Railton explores the connections between America’s past and present.

As is the case with too many American holidays, the meaning of Memorial Day has gradually evolved away from its more serious themes and toward more frivolous details: the start of summer (and the summer blockbuster season), a long weekend, barbeques and pool openings, sales. While all our national holidays would benefit from a return to their focal subjects and commemorations, it seems particularly important that we do so with a holiday dedicated to the memory of those American men and women who have sacrificed their lives in our military conflicts and wars across the centuries.

Yet there is an additional layer to Memorial Day’s forgotten histories: the holiday’s origins, in the immediate aftermath of the Civil War, as Decoration Day. And better remembering Decoration Day does not simply help us further contextualize our contemporary Memorial Day celebrations — it illustrates some of the worst and the best of Reconstruction, race, and American history and identity.

Decoration Day’s precise historical origins remain somewhat uncertain and debated, but historian David Blight has convincingly traced them to a specific community and post-war moment: formerly enslaved African Americans in Charleston, South Carolina placing flowers on the graves of Union Army soldiers in May 1865 (less than a month after the Civil War’s conclusion). As Blight has argued, from this striking singular moment, a wider tradition arose over the next few years, with both African Americans and others decorating soldiers’ graves throughout the nation’s many Civil War cemeteries.

One of the clearest representations of this evolving Decoration Day tradition can be found in a short story, Constance Fenimore Woolson’s “Rodman the Keeper” (1880). Woolson’s titular protagonist is a Union veteran working at a Civil War cemetery in an unnamed Southern state, “keeping” the graves of Union and Confederate casualties alike. The story as a whole traces his complex relationship to a dying Southern veteran and the veteran’s bitter daughter, but at its heart is Rodman’s observation of a group of African Americans decorating Union graves. “One morning in May,” Woolson writes, “the [town’s] whole population of black faces went out to the national cemetery with their flowers on the day when, throughout the North, spring blossoms were laid on the graves of the soldiers.”

As the phrase “throughout the North” reflects, by the late 1870s the local and somewhat informal Decoration Day tradition had begun to evolve into a formalized national commemoration, one that Woolson refers to in her text as “Memorial Day.” While that evolution partly built on the kinds of local and African American celebrations that Woolson’s story features, it also too often illustrated a more troubling national trend: the move, with the end of Reconstruction, away from memories of slavery and activism for African American rights and toward the kinds of unifying, white supremacist narratives reflected in the deification of Robert E. Lee.

A May 1877 speech in New York City exemplifies that national shift. For many years the Brooklyn Academy of Music (BAM) had presented a Decoration Day speech, generally featuring Union veterans and former abolitionists. But in 1877, BAM invited instead Roger A. Pryor, a former Confederate general who had moved to the city after the war and become a prominent Democratic politician and opponent of Reconstruction. Pryor’s Decoration Day address offered that perspective on recent American history, calling Reconstruction a “dismal period … devised to balk the ambition of the white race.” Yet he also sought to revise his audience’s understanding of “the cause of secession,” and in so doing to contribute to the national shift away from memories of slavery and race and toward the Confederate sympathies of the developing Lost Cause narrative.

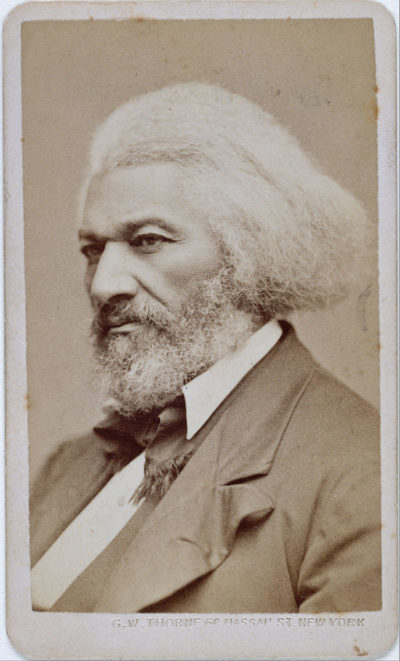

Such shifts likewise changed the meaning of Decoration (and subsequently Memorial) Day, away from African American commemorations of the Civil War and abolition and toward a broader and more conciliatory emphasis on white soldiers and heroism from both sides of the conflict. Yet that narrative was not and is not the only way to remember and celebrate the holiday and its meanings, and in his May 30, 1871 Decoration Day address at Virginia’s Arlington National Cemetery, Frederick Douglass offered a distinct, impassioned, and inspiring rejoinder to such revisionist histories and argument for the holiday’s vital national significance.

In his short speech, entitled “The Unknown Loyal Dead,” Douglass seeks to honor “the solemn rites of this hour and place,” to give voice to the cemetery’s “silent, subtle and all-pervading eloquence, far more touching, impressive, and thrilling than living lips have ever uttered.” He notes that, “We are sometimes asked, in the name of patriotism, to forget the merits of this fearful struggle, and to remember with equal admiration those who struck at the nation’s life and those who struck to save it, those who fought for slavery and those who fought for liberty and justice.” And he offers a potent challenge to that perspective and reminder of the war’s (and thus the holiday’s) central subjects, concluding,

But we are not here to applaud manly courage, save as it has been displayed in a noble cause. We must never forget that victory to the rebellion meant death to the republic. We must never forget that the loyal soldiers who rest beneath this sod flung themselves between the nation and the nation’s destroyers. If today we have a country not boiling in an agony of blood, … if now we have a united country, no longer cursed by the hell-black system of human bondage, if the American name is no longer a by-word and a hissing to a mocking earth, if the star-spangled banner floats only over free American citizens in every quarter of the land, and our country has before it a long and glorious career of justice, liberty, and civilization, we are indebted to the unselfish devotion of the noble army who rest in these honored graves all around us.

Memorial Day represents an opportunity to remember all those American soldiers who have given their lives for their country. Yet there is a particular significance to remembering not just this group of Civil War soldiers, but also and especially the holiday that first commemorated them and the American community that initiated that holiday. If the shift away from Decoration Day too often reflected a frustrating abandonment of that community, we can return to those crucial American histories by better remembering Memorial Day’s origins.

Featured image: A 1883 political cartoon by Bernhard Gillam shows politicians and others in a cemetery on Memorial Day, each seeming to mourn at gravestones bearing the names of their political losses. (Library of Congress)

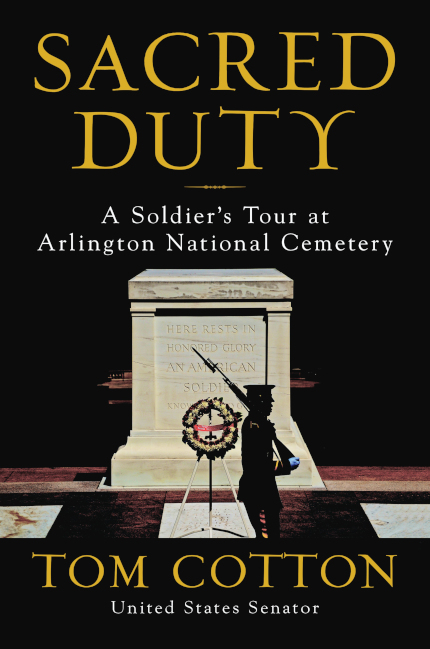

Sacred Duty

Every headstone at Arlington tells a story. These are tales of heroes, I thought as I placed the toe of my combat boot against the white marble. I pulled a miniature American flag out of my assault pack and pushed it three inches into the ground at my heel.

I stepped aside to inspect it, making sure it met the standard that we had briefed to our troops: “vertical and perpendicular to the headstone.” Satisfied, I moved to the next headstone to keep up with my soldiers. Having started this row, I had to complete it.

One soldier per row was the rule; otherwise, different boot sizes might disrupt the perfect symmetry of the headstones and flags.

I planted flag after flag, as did the soldiers on the rows around me. Bending over to plant those flags brought me eye-level with the lettering on those marble stones. The stories continued with each one. Distinguished Service Cross. Silver Star. Bronze Star. Purple Heart. America’s wars marched by. Iraq. Afghanistan. Vietnam. Korea. World War II. World War I. Some soldiers died in very old age; others still were teenagers. Crosses, Stars of David, Crescents and Stars. Every religion, every race, every age, every region of America is represented in these fields of stone.

I came upon the grave site of a Medal of Honor recipient. I paused, came to attention, and saluted. The Medal of Honor is the nation’s highest decoration for battlefield valor. By military custom, all soldiers salute Medal of Honor recipients irrespective of their rank, in life and in death. We had reminded our soldiers of this courtesy; hundreds of grave sites would receive salutes that afternoon. I planted this hero’s flag and kept moving.

On some headstones sat a small memento: a rank or unit patch, a military coin, a seashell, sometimes just a penny or even a rock. Each was a sign that someone—maybe family or friends, perhaps even a battle buddy who lived because of his friend’s ultimate sacrifice—had visited, and honored, and mourned.

For those of us who had been downrange, the sight was equally comforting and jarring—a sign that we would be remembered in death, but also a reminder of just how close some of us had come to resting here ourselves. I left those mementos undisturbed.

After a while, my hand began to hurt from pushing on the pointed, gold tips of the flags. There had been no rain that week, so the ground was hard. I questioned my soldiers how they were moving so fast and seemingly pain-free. They asked if I was using a bottle cap, and I said no. Several shook their heads in disbelief; forgetting a bottle cap was apparently a mistake on par with forgetting one’s rifle or night-vision goggles on patrol in Iraq. Those kinds of little tricks and techniques were not briefed in the day’s written order, but rather get passed down from seasoned soldiers. These details often make the difference between mission success or failure in the Army, whether in combat or stateside. After some good-natured ribbing, a young private squared me away with a spare cap.

We finished up our last section and got word over the radio to go place flags in the Columbarium, where open-air buildings contained thousands of urns in niches. Walking down Arlington’s leafy avenues, we passed Section 60, where soldiers killed in Iraq and Afghanistan were laid to rest if their families chose Arlington as their eternal home. Unlike in the sections we had just completed, several visitors and mourners were present. Some had settled in for a while on blankets or lawn chairs. Others walked among the headstones. Even from a respectful distance, we could see the sense of loss and grief on their faces.

Once we finished the Columbarium, “mission complete” came over the radio and we began the long walk up Arlington’s hills and back to Fort Myer. In just a few hours, we had placed a flag at every grave site in this sacred ground, more than two hundred thousand of them. From President John F. Kennedy to the Unknown Soldiers to the youngest privates from our oldest wars, every hero of Arlington had a few moments that day with a soldier who, in this simple act of remembrance, delivered a powerful message to the dead and the living alike: you are not forgotten.

The Thursday before Memorial Day is known as Flags In at Arlington National Cemetery. The soldiers who place the flags at every grave site in the cemetery belong to the 3rd United States Infantry Regiment, better known as The Old Guard. Since 1948, The Old Guard has served at Arlington as the Army’s official ceremonial unit and escort to the president.

I walked through Arlington for Flags In with The Old Guard in 2018. “What better way to show the nation and our fellow soldiers that we care and we never forget,” observed Colonel Jason Garkey, the regimental commander. As we walked along streets named for legends like Grant and Pershing, he added, “This mission is really important for The Old Guard, too. It’s the only day of the year when the whole regiment operates together. It gives all my soldiers—all my mechanics and medics and cooks—a chance to come perform our mission in the cemetery.”

Flags In carries a special meaning for our citizens, too, judging by our conversations that afternoon. Col. Garkey greeted every civilian who approached us. Most were curious about the soldiers they saw walking across the cemetery. As he explained Flags In and The Old Guard, without fail they expressed their fascination and gratitude. In Section 60, we encountered families and friends paying early Memorial Day visits to their loved ones. Col. Garkey thanked them for their sacrifice, and they thanked him for his service and for remembering their fallen heroes. He never mentioned that those were his soldiers or that he had planted flags that day at the graves of his own friends and mentors.

My turn at Flags In came in 2007 during my own tour at Arlington. I had joined The Old Guard a couple of months earlier, after serving a tour in Iraq with the 101st Airborne Division. My path to The Old Guard was unusual—like my journey into the Army itself.

It began the morning of 9/11 in a law-school classroom. In those days before smartphones, we did not learn that America was under attack until class ended, almost an hour after the first airplane hit the World Trade Center. But my life changed in that moment. I knew the life I had anticipated in the law was over.

I wanted to serve our country in uniform on the front lines. I finished school and worked for a couple of years to repay my student loans, time I also used to get prepared physically and mentally for the Army. It took my recruiter by surprise when I told him that I wanted to be an infantryman, not a JAG lawyer. To his credit, he signed me up and shipped me out, setting me on the path to Iraq. After more than a year in training, I joined the 101st in Baghdad in 2006, taking over a platoon of Screaming Eagles.

We conducted raids, laid in ambushes, dodged roadside bombs and sniper fire, and sorted out the dead in a vicious sectarian war. And at the end of that tour, to my surprise, the Army gave me orders to The Old Guard, even though I had not applied to the all-volunteer regiment. I knew The Old Guard was a special unit. The regiment has some of the highest eligibility standards in the entire military. Old Guard alumni were among the most squared-away soldiers I knew in the Army. And the mission set—not only conducting daily funerals in Arlington, but also world-famous ceremonies like presidential inaugurations and state funerals—called for the Army’s best soldiers, performing at the highest levels. I looked forward to the assignment and I felt honored while serving at Arlington.

But I did not fully appreciate our nation’s special reverence for The Old Guard and Arlington until years later, when I entered public life. A political newcomer, I spent the early months of my first campaign introducing myself to Arkansans, telling them about myself and what I hoped to accomplish for them. The most common question I got was not about Iraq or Afghanistan or about iconic Army institutions like Ranger School. No, the most common question, by far, was about my service with The Old Guard. The same holds true today; when I speak around the country to new audiences, questions about The Old Guard outnumber all the others. Likewise, thousands of Arkansans visit me each year in Washington. When I ask them about the highlight of their trip, Arlington tops the list.

The Old Guard embodies the meaning of words such as patriotism, duty, honor, and respect. These soldiers are the most prominent public face of our Army, perform the sacred last rites for our fallen heroes, and watch over them into eternity. The Old Guard represents to the public what is best in our military, which itself represents what is best in us as a nation.

As Old Guard soldiers, we viewed the funerals through their eyes as we trained, prepared our uniforms, and performed the rituals of Arlington. We held ourselves to the standard of perfection in sweltering heat, frigid cold, and driving rain. Every funeral was a no-fail, zero-defect mission, whether we honored a famous general in front of hundreds of mourners or a humble private at an unattended funeral.

Although funerals are The Old Guard’s highest-priority mission, the regiment also performs in ceremonies around the capital almost every day. From welcoming foreign leaders at the White House and the Pentagon to honoring retiring soldiers at Fort Myer, The Old Guard represents the discipline and skill of all soldiers. Among its ranks, The Old Guard boasts world-class musicians, the military’s most elite color guard, and the Army’s premier drill team. They carry the Army story and values to worldwide audiences and the smallest gatherings alike, always with pride and precision.

Arlington National Cemetery and The Old Guard transcend politics. We live in politically divided times, to be sure. Yet the military remains our nation’s most respected institution, and the fields of Arlington are one place where we can set aside our differences. Which itself is something of a historic irony, because our national cemetery was birthed in the most divisive time in our nation’s history, when Americans killed each other on such a mass scale that a farm across the river from our capital became the graveyard for those war dead. Perhaps because of those bloody origins, Arlington National Cemetery emerged from the ashes of the Civil War as a place dedicated to healing, reconciliation, and remembrance.

What the Old Guard does inside the gates of Arlington is a living testament to the noble truths and fierce courage that have built and sustained America. We go to great lengths to recover fallen comrades, we honor them in the most precise and exacting ceremonies, we set aside national holidays to remember and celebrate them. We do these things for them, but also for us, the living. Their stories of heroism, of sacrifice, of patriotism remind us of what is best in ourselves, and they teach our children what is best in America.

On the eve of the war that transformed this farm into a national cemetery, President Abraham Lincoln pleaded for unity in his First Inaugural. “Though passion may have strained, it must not break our bonds of affection,” he acknowledged, while appealing to the “mystic chords of memory, stretching from every battle-field, and patriot grave, to every living heart and hearthstone, all over this broad land.” In our days, as in his, passions can no doubt strain our bonds of affection, but those mystic chords of memory still stretch from the patriot graves of Arlington across our great land, calling forth yet again “the better angels of our nature.”

For the fallen and their families, The Old Guard honors their service and sacrifice. For us, the living, The Old Guard embodies our respect, our gratitude, our love for those who have borne the battles of a great nation—and those who will bear the burdens of tomorrow. No one summed up better what The Old Guard of Arlington means for our nation than did Sergeant Major of the Army Dan Dailey. He recalled a moment with a foreign military leader while driving through the cemetery to lay a wreath at the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier. “I was explaining what The Old Guard does and he was looking out the window at all those headstones. After a long pause, still looking at the headstones, he said, ‘Now I know why your soldiers fight so hard. You take better care of your dead than we do our living.’ ”

From the book “Sacred Duty: A Soldier’s Tour at Arlington National Cemetery” by Tom Cotton. Copyright © 2019 by Thomas B. Cotton. Reprinted by permission of William Morrow, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers.

Featured image: U.S. Army.

Six Fun (or Frustrating) Facts about Thanksgiving and Other Federal Holidays

When it comes to federal holidays in America, most people don’t think much about them unless they’re happy for an extra day off of work. But behind the list of dates on your job benefits form are Congressional oversight, rules, compromises, and, occasionally, bitter feuds. With Veterans Day and Thanksgiving, November boasts two federal holidays; Martin Luther King, Jr. Day was also signed into law by President Ronald Reagan 25 years ago this month. In appreciation of those dates, we’re taking a look at a few things you might not know about your federal holidays.

1. There are Ten Official Federal Holidays

Federal holidays receive their designations from the U.S. Congress. Their jurisdiction includes federal institutions and their employees, and the District of Columbia; individual states and cities usually map their own observances onto the various holidays so that schools or other entities may be closed. The ten holidays by their official names are: New Year’s Day; Birthday of Martin Luther King, Jr.; Washington’s Birthday; Memorial Day; Independence Day; Labor Day; Columbus Day; Veterans Day; Thanksgiving Day; and Christmas Day.

2. MLK is the Newest Day

The most recently created federal holiday is the Birthday of Martin Luther King, Jr., commonly referred to as Martin Luther King, Jr. Day or abbreviated as MLK. The first bill to suggest the holiday went before Congress in 1979, but missed passage by five votes. The issue gained traction with the public, generating petitions and endorsements from celebrities like Stevie Wonder. Debate became incredibly contentious in the Senate; when North Carolina Senator Jesse Helms led opposition to the holiday and produced a document that he claimed contained proof of King’s association with communists, New York Senator Daniel Patrick Moynihan threw the papers on the Senate floor and stomped on them. On November 2, 1983, President Reagan signed the bill, with observances set to begin in 1986; however, some individual states resisted implementing the day as a paid holiday for years. Arizona’s resistance lost the state a chance to host Super Bowl XXVII. MLK wasn’t acknowledged as a state holiday in South Carolina until 2000.

3. It’s Still Washington’s Birthday

It’s widely believed that George Washington’s birthday was simply combined with Abraham Lincoln’s birthday to create President’s Day. Despite the name being in common use on calendars, President’s Day really only exists at state levels. The official federal name remains Washington’s Birthday; however, depending on your state, you could live a place that celebrates that, Presidents’ Day, President’s Day (note the apostrophe moved), Presidents Day (note the lack of apostrophe) or Washington’s and Lincoln’s Birthday. Colorado and Ohio call it Washington-Lincoln Day, Alabama throws in Thomas Jefferson, and Arkansas chooses to also recognize Daisy Gatson Bates, the newspaper owner and civil rights leader that advised and the aided the students known as the Little Rock Nine.

4. Columbus Day is Falling Out of Favor at the Local Level

Of the ten federal holidays, Columbus Day continues to be the one that generates the most controversy. Apart from the fact that Columbus never actually set foot in what is now the United States, much more has been learned and understood about his poor and violent treatment of the people of Central America. Though there is strong support in some quarters for keeping the holiday as is, particularly among many Italian-Americans who view it with a sense of pride, many states and cities have begun dismissing or replacing the holiday. Florida, Hawaii, Vermont, South Dakota, and Alaska not only do not recognize it, but have replaced it with Indigenous People’s Day. Iowa and Nevada don’t recognize it, but have state laws on the books to “proclaim” it; it is also not an official holiday in Oregon. As of 2017, more than 55 major American cities proclaim Indigenous People’s Day instead of Columbus Day. The United Native America group actively campaigns to drop it at the federal level.

5. Memorial Day and Veterans Day Are Not the Same Thing

The U.S. Department for Veterans Affairs, as you might expect, says it best: “ Many people confuse Memorial Day and Veterans Day. Memorial Day is a day for remembering and honoring military personnel who died in the service of their country, particularly those who died in battle or as a result of wounds sustained in battle. While those who died are also remembered, Veterans Day is the day set aside to thank and honor ALL those who served honorably in the military — in wartime or peacetime.” The placement of Veterans Day on November 11 is owed to the Armistice that ended World War I on that date in 1918; in fact, the day was called Armistice Day until a change was made by Congress in 1954. The history of Memorial Day, and its origins as Decoration Day, was covered by our Saturday Evening Post archivist Jeff Nilsson in 2009.

6. And You Thought Family Thanksgiving Could Be Contentious . . .

Almost since the founding of the United States, the government has called for national days of prayer or the giving of thanks. Obviously, this tradition goes back to the pilgrims, but actual government recognition started with a proclamation from George Washington in 1789; he designated a Thanksgiving Day for the 26th of November. For decades after, Thanksgiving Days were declared off and on, with state and territorial governors making declarations as well. In 1863, in the midst of the Civil War, Lincoln declared another national Thanksgiving Day, fixing it on the last Thursday of November.

That day held for the most part until 1939. Then, President Franklin D. Roosevelt, upon advice from department store

magnate Fred Lazarus Jr, decided to take advantage of a five-week November and designate Thanksgiving as the next-to-last Thursday of the month. The idea was to promote more shopping and commerce to help combat the lingering effects of the Great Depression. Prior to that time, it was considered unseemly to promote holiday shopping before Thanksgiving, and this would give both shoppers and businesses an extra week. Republicans in Congress objected, and discontent broke across state lines, with 23 states acknowledging Roosevelt’s date and 22 sticking to the last Thursday; Texas decided to take both days off. After two more years of disagreement, both houses of Congress passed a joint resolution that made Thanksgiving the fourth Thursday of November; that meant that in some years it would be the last Thursday, and other years it would be next-to-last, depending on how the calendar fell. FDR signed the bill on December 26th, 1941, enshrining Thanksgiving Day as an official federal holiday.