North Country Girl: Chapter 63 — Chocolate, Bars, and Bears

For more about Gay Haubner’s life in the North Country, read the other chapters in her serialized memoir.

My tenure as secretary to Kathy Keeton, publisher of Viva and associate publisher of Penthouse, had been a wild mouse of a ride. The man who hired me tried to coerce me into sex, I had been an ignominious failure as a fake Penthouse Pet, and now I had attained almost human status in Miss Keeton’s eyes by finding and returning a $50,000 bauble her jeweler had dropped in her office’s white shag carpet.

There were few beings Miss Keeton deigned to speak to civilly: Bob Guccione, Pets, Viva ́s art director Rowan, her jeweler, the Rhodesian Ridgebacks, and advertisers, existing and prospective. For everyone else, Miss Keeton had perfected a look and attitude that relegated them to the status of bad waiters, or even bad busboys. If you were a mere editor, she had the ability to speak to the air in front of you while simultaneously staring through you.

But for the first time Kathy looked in my direction when she tossed off her demands and occasionally said please and thank you as if she might mean it. A few days following the affair of the missing tennis bracelet, she popped her head into my cubicle.

“Gay. I recall that you had some writing in your background. Would you be interested in doing an article for Viva?”

This reward for the return of the bracelet was almost as good as the diamond stud earrings I had been hoping for.

“Oh yes, Miss Keeton! I’d love to!” I gushed, praying that the assignment would not be something like “How to Find Your Own G-Spot” or “Are You Bi-Curious?” or any other supposedly erotic claptrap that would lower me even further in the eyes of Viva’s editorial staff.

The article I was to write was not about sex. It was about the next best thing: chocolate.

Viva’s advertising department was desperate to have something in the magazine they could tote around to media buyers at ad agencies that said “Look! No more penises! We’re not hardcore porn, just a regular woman’s magazine!” The delusional saleswomen wanted Viva to run an article on chocolate, in the hope that they could lure Nestlé or Hershey’s into the magazine. They convinced Kathy, who dropped into the next editorial meeting to strongly suggest that a story on “The Joy of Chocolate” be published ASAP. The editors, equally delusional in their belief that they were independent, balked at such froufrou subject matter appearing in their magazine. My sole ally, managing editor Debby Dichter, hinted to Miss Keeton that I would probably love to write the piece.

But the idea for an article for chocolate had banged around Kathy’s head too long, and had morphed into something else entirely, something consistent with Kathy’s belief that the Viva readers were all versions of her.

“Gay, don’t include any rubbish, no Godiva, ghastly stuff. I want only the top end, the most exclusive purveyors of chocolate.” I had my title: “Haut Chocolate.”

This writing assignment made me happy, but it did not make me any new friends. Viva’s editors, who tended to be politically to the left of Castro and who were never quite on my side to begin with, hated having the ad staff dictate what articles should run in the magazine. The fact that I was writing this puff piece — Miss Keeton’s secretary! — made it even worse.

What made up for my pariah status was the discovery that when you work for a magazine, you get free stuff.

All it took was a few phone calls and I had boxes and boxes of beautifully crafted and utterly delicious truffles and pralines from Teuscher and Neuchatel and other European chocolatiers messengered to me. I made a small uptick in my reputation by personally delivering each box to a different Viva editor. Then I called and requested more gift-wrapped boxes of chocolates to photograph for the article.

I did not fare as well with the ad saleswomen. Beverly Wardale, the alpha female of that wolf pack, showed up at an editorial meeting shaking the layouts of my article.

“What the bloody hell is this?” she demanded. “These companies don’t advertise! You can’t even buy these bloomin’ chocs anywhere except Fifth Avenue and Switzerland!” The editors all cut their eyes at Kathy, and Beverly, realizing that the article had Kathy’s chocolaty fingerprints all over it, departed in a huff, tossing the pages behind her.

***

I had been at Viva long enough to accumulate a week’s paid vacation, but I had not accumulated the money to pay for a trip anywhere, unless it was via subway. My artist boyfriend, Michael and I were pretty much living on my $12,500 secretarial salary. The monthly check he received for his illustrations in Esquire magazine went right back out the door in the form of child support for his two kids back in Chicago.

Michael was starting to get illustration assignments from astute art directors who recognized his uncanny ability to capture personality in his portraits. He did not draw caricatures; he drew character. Michael’s genius was his ability to express in a few black lines and a charcoal wash the inner person. Michael could see, wanted to see, below the skin, past the face one presents to the world, and he looked with equal parts of empathy and curiosity.

Michael approached everyone with a wide open heart and whip-smart intelligence. He wanted to know what made them tick, what they liked, what motivated them. He was able to find common ground with anyone: he could talk sports, art, music, books, and movies, and was always more interested in your opinion than his own. I never introduced him to a single person who did not want to be his friend.

Both Viva and Penthouse were too slick, too air-brushed to have any use for Michael’s intellectual style of drawing. I dragged him and his portfolio up there anyway, and had him meet as many of the staff as I could buttonhole in a loop about the office. Michael’s charm turned out to be more effective in redeeming my reputation than a $100 box of truffles.

Even Viva’s editor, Gini, regarded me with a less jaundiced eye after she met Michael. Her own boyfriend, Bill Plympton, was also a cartoonist and illustrator, although a considerably more successful one than Michael.

My first friend at Viva, Debby Dichter, had long been a fan; she may have had a small crush on Michael. One night at dinner, Michael confessed to her, “I feel terrible” (he did, Michael was really really good at guilt) “that I can’t afford to take Gay on a vacation. She deserves it,” and he looked at me as if I were the moon and the stars.

Although I had mentioned our lack of funds to Debby on the few occasions it was my turn to complain about something, to please Michael Debby now sprang into action.

“My family has a house on Cape Cod, in Wellfleet. You could use it. It wouldn’t cost you anything.”

Michael and I set off in a borrowed car to a borrowed house, which turned out to be the perfect Cape Codder: an elegant two-story modern home, all glass and wood, set on a thickly treed lot, no neighbors in sight. I was thrilled, as was Michael, until it started to get dark.

Michael peered into the crepuscular forest and shuddered.

“There’s nobody around. What do you think is out there?”

“Owls, sleeping chipmunks…”

“Bears?” asked Michael. Up till now, to Michael a bear meant a burly man wearing a football helmet (or his young baseball playing relative, a Chicago Cub). I had grown up in a town that was a regular commute for bears; the classy Hotel Duluth had The Black Bear Lounge, as one had once wandered through the lobby, a bear in search of a beer in a bar.

“Michael, the closest bear is probably in the Boston zoo.”

“There are other big animals though,” worried Michael, as dusk erased the space between the trees, leaving only a few birches glowing like skinny ghosts. “Like ah, moose…moose and…”

“And squirrel?” I said in my best Boris Badenov voice. It didn’t help. Michael turned on every light in the house, including the garage and the back door. The master bedroom, with its big windows and woodsy view, was on the ground floor, too close to marauding squirrels; we slept in the attic, sharing a twin bed under the gleam of a Tinkerbell nightlight.

Michael was much happier in Provincetown, with its paved streets, stores, restaurants we couldn’t afford, art galleries that were not yet open for the season, and bars. He especially liked one bar that offered a 10:00 a.m. happy hour to accommodate the fishing crews. We ended up spending most of the day in that bar, a day I had planned on visiting the famous Cape Cod dunes, my goal a pilgrimage to the primitive (no electricity, no running water) shacks where Norman Mailer, Jackson Pollock, Eugene O’Neill, and Tennessee Williams had created masterpieces. Michael had agreed to this plan, but it was now almost three o’clock and I had reached my tolerance for day drinking.

We arrived at the dunes at the exact moment when the western light casts a weird spell over the lunar landscape, flinging deep violet shadows across that treeless spit of land, flattening everything out, and warping perspective; it was like being in a real-live Mystery Spot. We could see one shack on top of a nearby dune; after a half-hour trudge through the sand, the shack actually seemed farther away.

Michael turned around. The only sign of which direction we had come from were our footprints, slowly filling in with sand.

“We’re lost!” Michael freaked out. Outside of that gray, dilapidated cabin, which was either a block or a mile away, there were no man-made objects in sight.

I could not take this seriously. “At least there’s no bears,” I ribbed him. Michael looked at me as if I were a heartless monster who had lured him to this death trap.

“C’mon Michael, you have got to be kidding.” He wasn’t. “Cape Cod is like a mile wide here. It’s impossible to get lost, we walk one way and we hit the sea, the other and we hit Highway 6.”

“Or we could just walk in circles till we die.” I gave up, took Michael’s hand and, turning our backs to the setting sun, we returned to the parking lot and then on Michael’s insistence, back to the Fisherman’s Arms. He desperately needed a drink.

By the end of the week, Michael had spent so much time in that bar that he was practically an honorary fisherman, having charmed even the crabby old lobstermen. He justified his bar tab by the fact that when I came to pick him up after my solo visit to the Pilgrim Spring or retracing Thoreau’s Cape Cod walks or bird-watching at the kettle ponds, he was not allowed to leave without a flounder or haddock or pair of lobsters for our dinner. I gave a silent thanks to the gay waiters at Arnie’s back in Chicago for teaching the lowly coat check girl how to bone a Dover Sole and crack open a lobster.

North Country Girl: Chapter 57 — Broken-Hearted in Chicago

For more about Gay Haubner’s life in the North Country, read the other chapters in her serialized memoir.

My accidental career as a part-time model and part-time pornographer for Oui, a men’s magazine, paid the bills, including my half of the rent on the Art Nouveau apartment my illustrator boyfriend Michael and I now shared, and I was even stashing a bit of money in my bank account.

I had enough saved that after two winter-y months of dragging my modeling portfolio through Chicago blizzards and howling hawk wind, showing up at go-sees with chapped cheeks, runny mascara and frozen feet, I put one of those icy feet down and told Michael we had to take a vacation someplace warm, like the rest of civilized Chicago did. Michael looked horrified at this extravagance; I don’t think his own parents, who had met in a camp for displaced persons at the close of World War II, ever took Michael and his brother on a family vacation.

“I’ll pay for the whole thing,” I mollified him, and set about looking for the cheapest tropical vacation package I could find. A sympathetic travel agent sent us to a “resort” on a tiny off island of the Bahamas, a trip that required one jet, one Piper Cub, and one ancient powerboat that chugged for hours through the waves at the perfect angle to completely soak us and our luggage.

Cheapskate Key had a tetherball, a small sailboat, and a bar. The tetherball and Sunfish were included with the price of the room, the bar was not. The bar was where Michael retreated, after getting smacked in the face with the tetherball, stranded out in the ocean on the Sunfish (that was my fault, how hard can it be to sail a little boat, I thought?), and being sick to his stomach at the only tourist attraction on the island: watching the fish cannery dump its chum into the shark-infested waters at sunset.

By the end of the week, I was tanned and rested, Michael was pale and suffering from a seven-day hangover and anxious to get back to work and his kids. He had run up a stupendous bar tab. One by one, I tore out all my American Express travelers’ checks, signed them, and handed them over to the hotel manager. “Do you have any money?” I asked Michael, who pulled out a few crumpled ones, which got us on the airport bus to the El and then back home to Burton Place, where Michael swore he would never leave the city again.

Winter eventually eased Chicago out of its icy grip, and spring and summer smiled on the new lovers. Michael and I were creating a sweet, cozy life together, tucked away in our Hobbit apartment. We were much richer in love than money and rarely went out, even for a cheap curry. I tried to make us romantic dinners in a kitchen that contained a sink, a small fridge, and a stove, but absolutely no counter space, drawers, or cabinets. I guess artists are not supposed to cook.

At night, Michael searched the Chicago TV stations for old black and white movies; he was a great fan of Frank Capra and cried every time he heard Jimmy Stewart say, “Zuzu’s petals.” We cuddled and kissed on the sofa, watching Mr. Deeds go to Washington or Sergeant York go to war or Lillian Gish and Robert Mitchum face off in The Night of the Hunter. My young dream of love, being half of a couple that needed nothing and no one but each other, had come true, except it was with a different Michael.

I was finally allowed to meet Michael’s kids who were both adorable moppets, even though the younger kid left the front door open and my little Yorkie Groucho ventured out into the Chicago night, never to return, and the older one took my bike out for an unauthorized spin, making it less than a block before a bigger kid shoved him off and stole it. All was forgiven. I was crazy about their father, whose “I love yous” and kisses soothed and tingled me at the same time.

In the midst of all this bliss, on a day I thought I looked especially cute in a Betsy Johnson pink-flowered minidress bought from a toothpick-chewing guy who sold designer clothes out of the trunk of his car, I flounced into the Oui offices to drop off my newest brilliant submissions and pick up a small check. The moment I walked in the door, I intuited something weird in the atmosphere, like the oxygen had been sucked out, or someone had set a small fire. Everyone in the office had a different odd expression, from grim death on the secretaries’ faces to editor Gerald Sussman’s ape-like grin as he bounced about on his tiny feet.

John beckoned me into his office. “We’re moving to Los Angles,” he said.

“Who? You? Oui?” I sounded like a deranged songbird. “What’s happening?”

“Everyone’s going. Well, the editors, art directors…” John rambled on, stacking up papers without looking at them, talking about how unhappy his wife was about leaving her friends and her family, how he’d have to buy a car, find a place to live. He worried if there were any fellow poets in L.A., that most unpoetic of cities, or just television studios and endless freeways.

Yes, yes. But what about me?

“I can still write for you though? We could mail stuff back and forth?” I tried to plant a look on my face that was both writerly and too cute to turn down.

John shook his head. “Not going to work. It would take too long, everything’s going to be crazy after the move…”

I handed him my hysterically funny short humor pieces, my best yet, and hoped that he would wait until I left to toss them in the bin. John found my check in a drawer and said, “I’m sorry.”

I autopiloted the walk home, my head full of mental arithmetic and plans: how much money was in my bank account, rent, electric, phone, what conventions were coming up, what photographers I hadn’t seen for a while.

Big events in my life never arrive by themselves, they insist on bringing along a friend.

My news — no more writing assignments, no more Oui modeling jobs, and we can say goodbye to our pal and neighbor, George, who was headed for L.A. with the rest of Oui’s art department — went unheard by Michael, who was waving a letter in my face.

“Esquire! Esquire magazine! They want me to illustrate Harry Crews’ column!”

Crews was a southern humorist who wrote about moonshine, coonhounds, hunting for squirrels, and bass fishing; his column in Esquire was called “Grits.”

Michael was a Chicago Jew who hated the outdoors, was afraid of trees, and had never seen a grit. Somehow an art director had decided these two would be perfect together. Michael was holding a contract from Esquire for a year’s worth of illustrations.

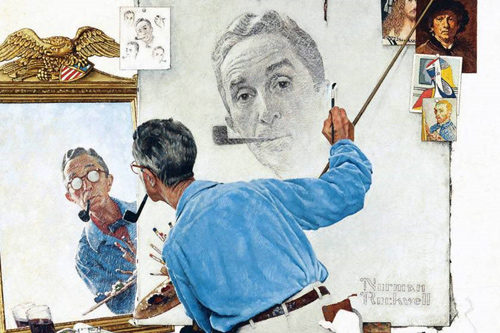

For Michael, this recognition from New York, from a magazine famous for its art and design, was the celestial sign he had been waiting for all his life, the confirmation he was following in the footsteps of his idols, Norman Rockwell and J.C. Leyendecker.

I was so happy for Michael that I could put aside my disappointment at the early death of my own writing career. After his first burst of exhilaration, however, Michael turned moody; one day I caught him brooding over a drawing, pencil posed unmoving over the paper, sad songs from Derek and the Dominos filling the apartment.

“C’mon,” I said as I kissed and stroked his balding head. “Let’s go out! Indian food. My treat.” I got a mumbled “Okay,” and Michael flipped the record over and went back to not drawing.

It was not the romantic, celebratory dinner I had imagined. The curry house was our special place, where I had first realized that I had fallen in love with this funny looking guy who made me laugh and claimed to adore me. He didn’t look so adoring now, as he shoved his vindaloo around his plate with a piece of naan and called the waiter over for his fourth Kingfisher beer. My attempts at happy conversation fell flat. I ate, and Michael drank in silence until he announced, “I’m moving to New York.”

Why was everything and everyone leaving for the coasts, after Chicago had finally generously bestowed on me a boyfriend, a semi-steady income, and a love nest apartment that was like living in a work of art?

“And me?” was my first and only thought. “Am I going with?” I asked.

Michael looked down and said, “I don’t know,” which was not the answer I had hoped for. My eyes prickled; I felt betrayed and angry and abandoned. In my mind I was shouting, “I didn’t want this! You wanted this! You told me you loved me!” but “I don’t understand,” was all I could say.

Michael did not understand either. We spent miserable hours that night plumbing his swirling thoughts and emotions: He loved me, felt desperately guilty about leaving his kids; he was worried about earning enough to pay child support and live on; he was moving to an unseen studio apartment sublet from a friend of a friend; and back, always returning to “I love you Gay, it’s just…”

The bottom line was he had to move to New York. That was all he knew and all he could deal with at the moment. We did not talk about my own crushed and battered feelings. And I was too self-centered and selfish to understand how leaving his adored children to follow his art was tearing Michael apart; his separation from his sons would be a wound he never recovered from. How could he leave his kids in Chicago and take his Playboy model girlfriend with him to New York?

In between our unhappy discussions of his tortured psyche, Michael packed up his apartment and said goodbye to his kids, weeping harder than they did and promising to fly them to New York as often as possible. I wandered up and downstairs, trying to stay out of the way of this family disunion. I picked at the few possessions I had kept with me over all the moves of the past three years and wondered what to do next. It would break my heart even more to live with just the memory of Michael in that magical Burton Place apartment, even if I could have afforded it on my own.

Suddenly I didn’t want to be in Chicago at all. I didn’t want to drag my portfolio around town in the freezing, blustering winter and the soupy, sticky, summer, or fight off handsy photographers, or murder my feet standing for hours on the cement floor of the convention center passing out brochures for power tools.

I called my old friend Mindy in Minneapolis, gave her my abridged story, and asked if I could stay with her for a few weeks.

I had last seen Mindy on her one and only visit to Chicago when I was still living with James, whom she took a deep dislike to after he offered her a Quaalude while I was in the shower and hinted that a threesome would be fun. Since then we kept touch through sporadic phone calls and lines scribbled inside funny greeting cards.

My friends are all generous spirits. Even though we had not spoken for months and months, Mindy said yes, come on up, she had room for me.

Michael and I said our goodbyes amid floods of tears. “What the hell am I doing?” Michael wept. I wondered that too. I gave him Mindy’s phone number and address and we parted, Michael off to conquer the illustration world in New York, me to do who the hell knew what in Minneapolis.

North Country Girl: Chapter 55 —A Chicago Courtship

For more about Gay Haubner’s life in the North Country, read the other chapters in her serialized memoir.

The best advice my mother ever gave me was, “Don’t get involved with anyone who has more problems than you do.” After James, with his morbid fear of gaining weight and getting old, who detested the idea of marriage and who had rejected his own child twice, who had lost his fortune and then his mind, I was determined to go out only with normal, problem-less men. Yet the next guy I dated turned out to have an unsavory fetish and a brain-damaged daughter. And Michael Trossman, an artist who flirted with me at a drug-soaked party, had an ex-wife, two kids, and a very complicated love life. Count me out, I thought. But work and loneliness and life conspired to bring me back to Michael and his bohemian digs at 155 Burton Place. A week after the MDA party where Michael and I met, Ann Geddes called me.

“You’ve got a booking at Oui, if you want it. It’s fully clothed, and it’s for promotional material, not anything in the magazine. I think you should take it.”

Oui was a Playboy publication, part of that great empire that devoured pretty young women who were desperate for money or fame. It was meant to appeal to younger readers, guys who grew up sneaking looks at their dad’s not-carefully-enough-hidden collection of Playboys, and who might otherwise be lured over to the more explicit Penthouse magazine.

Playboy’s Playmates were supposed to look like the girl next door if she ran around naked. The Playmates were posed cuddling a puppy or looking at a daisy; you couldn’t tell if they were getting ready to have sex or to bake cookies.

Oui ran racier photos of real and fake European girls, on the assumption that European equals sophistication equals hotter in the sack, girls wearing nothing but wooden shoes or holding a strategically placed baguette. Oui had no investigative journalism, no high-brow fiction, no interviews with presidents and movie stars. It was just pages and pages of sultry, nude women in berets interspersed with arch, sarcastic humor, painfully modeled after National Lampoon and falling short, and sensational, often fraudulent, articles such as “Is This the Man Who Ate Michael Rockefeller?”

My modeling job for Oui was to pose as the shortstop on an imaginary Oui all-girl baseball team. My uniform was a white and red pinstriped, deeply V-necked shirt and frighteningly small shorts that struggled to cover my butt.

It was my new pal George who handed me my baseball outfit and mitt. He had just been transferred from Playboy to Oui, where he was now the creative director. George had specifically requested me for this shoot.

Oh crap, I thought, here’s a guy who has already seen me naked, given me drugs. I was pretty sure where this was going and I pondered how to keep George at arm’s length and still be the nice, obliging model he would want to book again.

But George was all business in the photo studio, with the exception of darkroom pot breaks. There was not even flirtatious banter. When George came over to pose me, instead of doing it by placing one hand on a breast, the other on my butt like every other photographer did, he held me gently by the elbow.

First I stood with a baseball bat cocked on my shoulder while the photographer shot me from above. George shook the Polaroid, shook his head, probably at the unremarkable view down the front of my shirt, and then repositioned me. I bent over from the waist, baseball mitt on the patch of Astroturf, waiting for that groundball, my upside down face in an idiotic grin and my tight, tiny shorts riding even farther up my behind. George yelled “That’s it!” and we were done.

While signing my modeling voucher, George said, “Oh, we’re having a barbecue tonight, why don’t you come?”

I had planned to go home to my un-air-conditioned apartment, feed Groucho, my dog, drink copious amounts of iced tea, and read a book. But free food, free drinks, free drugs, pretty or smart people partying in those gorgeous apartments…“George, thanks, I’d love to.”

That evening the party was on the roof, the soundtrack was Curtis Mayfield, and while thankfully there was no MDA, the pot was strong. I climbed the ornate cast iron spiral stairs, which wobbled beneath me, and was greeted by a modest view of Chicago’s Near North neighborhood on one side, on the other the Cabrini Green housing project, as scary as Tolkien’s towers. Above this mundane cityscape stretched a twilight sky streaked with Technicolor reds and yellows in the west, deepening in the east to violet blue punctuated with a single star.

George escorted me over to Michael Trossman, who twinkled like that lone star. “The sky looks like a Maxfield Parrish,” I said.

“I knew you guys would get along,” said George proudly. Michael, the incurable romantic, had fallen out of love with Fred’s wife and in love with me.

“I can’t believe you’re a Playboy model,” Michael said. This, although technically true, required narrating my life story over several beers, hot dogs, and joints, a tale that featured how I had landed in Chicago, swept off my feet by James Rodgers.

When I was finished, Michael looked discouraged. “I’m not rich. I make art. It’s hard for me to come up with money for my kids each month.” The unspoken accusation of gold-digging stung. If I were a gold-digger I was the world’s worst: the only gold I had dug in my two years with James was the flimsy GAY pendant about my neck, one bracelet with a clasp for a promised charm that was never bought, and a chain necklace that turned out not to be gold at all.

So I let Michael kiss me. And then, in complete opposition to Anita Loos’ claim, it was just as easy to fall in love with a poor man as a rich one, although it took me a while. There was so much in Michael Trossman that reminded me of my original Michael, my first true love: the sly hidden intelligence, the European background, the moody, thin-skinned sensitivity, even though in looks he resembled him not at all: M. Trossman looked like a young Saul Bellow, M. Vlasdic like a young John Lennon.

Michael Trossman was the Romantic Artist; he had to be either madly in love or reeling from heartbreak. Just as LSD had been the philosopher’s stone that transmuted my teenage infatuation with Michael Vlasdic into a melding of souls, MDA was the elixir d’amour that sent Michael Trossman into a whirlwind of romance, buffeting him from Ronny’s girlfriend to Fred’s wife, to me, his new fixation.

After my escape from a semi-suicidal James and my refusal to play dominatrix in California, I believed I was through with men. I obviously had bad judgment or bad luck when it came to boyfriends. I was determined to spend my nights in my own bed, alone except for Groucho toothlessly drooling on my pillow. But it seems that the minute you decide you don’t want something, life insists that you do.

Michael courted me. He drew funny caricatures of me, signed “To my small girl” with XXX and OOO underneath. He was an enthusiastic amateur musician; he dragged his guitar out of the closet and sang love songs in goofy, off-key voices. Michael took me through his extensive record collection, peering up at me through his glasses to see if I liked what he liked; after years of living in a disco desert, I melted to English art rockers (Queen, Genesis, 10cc) and thrilled to the clamor and riot of punk (The Ramones, The Clash, Television). We sat close together on his couch listening to music, with the soft light beaming through the wall of translucent glass bricks, smoking pot, not needing to talk. I felt my shoulders loosening up and my heart thawing as “I’m Not in Love” filled the Art Nouveau living room.

I am most grateful to Michael for introducing me to music that had been right under my ears: the Chicago blues. Not a chorus or a chord of that soul-trembling sound had ever infiltrated my yuppie Near North enclave. Lightnin’ Hopkins, Hound Dog Taylor, Howlin’ Wolf, Muddy Waters, all alive and playing the blues just a few miles south of us, a whole new world to explore.

A few miles north of Burton Place was Wrigley Field. “I don’t really like sports,” I protested as Michael shoved me into an uptown El on a balmy September day.

Michael shook his head and kissed me and said, “But it’s the Cubs. The Cubbies! The only pro team named after a baby animal.”

As we stood in line for the bleacher seats, a man worked his way down the crowd, handed Michael a plastic razor, and muttered “Gillette Day.”

“Hey,” I sputtered. “Don’t I get a razor?”

“Um, they’re men’s razors.” That was annoying. I challenged the razor guy to describe exactly what made a razor suitable for a man but not for a woman. Why couldn’t I shave my legs with the razor he was passing out to the men? Beaten down, Mr. Gillette grudgingly handed me a razor, and flush with victory, I ordered “Make sure the rest of the women get one too,” and the three other women in line cheered. Michael congratulated me on my tiny feminist victory with a sweet nuzzle on the neck and led me out to the wonders of The Friendly Confines, Wrigley Field.

Coming up from the dim ticket area was like ascending into a different world. The sky stretched out above in an open expanse rarely seen in Chicago. The field was a lush green that every Duluth dad sowing grass seed or smearing sheep shit over his front lawn could only dream of. Across from us, stately and still unlighted, rose the grandeur of Wrigley Stadium, as noble a piece of Chicago history as the Rookery or the Museum of Science and Industry. We found places to sit in the full sun of the bleachers, and Michael pulled out a slightly grimy Cubs cap for me. “My son’s,” he apologized. I put on the cap and bought two beers in waxy cups from the vendor, and then we rose for the National Anthem.

I had yet to give my heart completely to Michael, but that day I fell in love with baseball, played as it should be, during the day, in plein air, even though the Cubs managed to blow a six-to-one lead over the Mets, much to the disgust of the raucous, filthy-mouthed, beer-soused bleacher bums around me. Michael was drinking at the rate of a beer an inning, but I slowed my own consumption after a long, winding, desperate search for the ladies’ room, which was situated as inconveniently as possible. I was sober enough to be alarmed when, in a late inning, I watched a tiny white sphere head skyward at the same time I heard the resounding crack of bat against ball. The sphere arced high and long, then plunged bleacherward as if it had been launched directly at me, getting bigger and closer until it suddenly dropped between my feet; I managed the one semi-athletic achievement of my life catching the ball on the bounce.

I started to say, “Would your kids like…” to Michael when a chorus started up: “Throw it back! Throw it back!” The offending ball had been homered by a Met. Michael shook his head, and I feebly tossed away the only baseball I have ever caught; it dropped into the ivy that enrobed the bleacher wall and may still be there to this day.

Squashed on the El with a thousand resigned Cub fans commiserating another loss, Michael teased out of me that my favorite food was Indian. That night he took me out to dinner, refusing to let me so much as leave the tip. A baseball game and dinner and I knew that he rarely spent a penny on himself, always busy hustling illustration jobs to pay rent and child support. Michael reached across the stained tablecloth and held my hand, and my heart gave an almost painful pang. How could a cheap curry and Kingfisher beer feel more romantic than champagne and steak Diane?

This was a new experience; I had never been wooed before. I made up my mind in the first 45 seconds of meeting a guy if I was going to sleep with him or not, and I had always stuck to my guns. Michael insisted that it wasn’t the MDA talking; he really had fallen in love with me. And as summer died away, the MDA parties with the rotating bedmates at Burton Place went from weekly to monthly and then never again, miraculously without any divorces, break-ups, or stabbings.

But in addition to his fun, funny, creative group of Burton Place denizens, who I adored and who seemed to like me (although maybe they were just glad to have me around since they were running out of wives and girlfriends for Michael to fall in love with), Michael had an ex-wife and two kids. His visitation schedule with his sons was erratic; sometimes he knew when they were coming, sometimes he called to warn me off, and sometimes I would be at his door and hear piping voices and pounding footsteps from above, my signal to turn around and go home.

Michael and I were alone one day at his place when there was a knock on the ground floor door and a woman’s voice yelling “Michael?” Panic shot through Michael’s face; he gestured me toward the bathroom, pushed me inside and shut the door before I realized what was happening. It was his ex-wife making a surprise visit in hopes of finding him with cash in hand. Those Art Nouveau apartments, all curves and rounded corners, carried sound beautifully; sitting on the tile floor I could hear every word she shrieked:

“A Playboy model? Really? I hope you know better than to have her around our sons.” Oh boy, I thought. What the other models had warned about posing for Playboy was true. I could get Rabin and Abbas to sit down over hummus and pita and the newspaper headline would read “Playboy Model Wins Nobel Peace Prize.”

Michael spent thirty seconds defending me before emptying his pockets and easing his ex-wife out the door. He released me from the bathroom, wearing such a miserable, guilt-ridden face I had to kiss it and make it all better. Michael’s German-Russian heritage meant that he did guilt as intensely as he did romance, and he had just locked the woman he claimed to love in the bathroom.

I hugged that big-nosed, balding man, knocking his geeky horn-rimmed glasses askew, and the magic cloak of love settled around me, a feeling identical to, yet complete different from, the one sparked by a tender, tenuous kiss with my first Michael, seven years before.

I tried to say, “I love you.” I could not speak the words; it felt like my giddy heart was swelling all the way up my throat. I had fallen for Michael: he was only slightly crazy, and so talented and funny that I was able to overlook the baggage of his two small children and had almost stopped noticing that he was not good-looking.

North Country Girl: Chapter 33 — The End of Childhood

For more about Gay Haubner’s life in the North Country, read the other chapters in her serialized memoir. This is the last chapter in the series.

Michael Vlasdic’s mother, the German professor, was always obliging; that summer, she taught a full load of classes, leaving Michael’s house delightfully parent-free for hours and hours. I loved Michael. I never wanted to leave his arms. To be with him, I had spent the past six months fretting over my personal monthly calendar — is it safe to have sex this day? The day after? After every “safe” day I was convinced I was pregnant and doomed right up until my trusty body proved otherwise.

Now the 60s made a further encroachment in Duluth: Planned Parenthood came to town. Until then, the only doctor I knew was my pediatrician, Dr. Bergman, who had seen me in my white Carters undies and examined me for pinworm.

The girl grapevine went into full swing. “I heard if you’re sixteen you can get birth control at Planned Parenthood and they don’t tell your parents,” said a wide-eyed Wendi Carlson. I was one of their first customers. I was so desperate to have as much sex as possible with Michael, to be free of the tyranny of the menstrual cycle, that I turned up at their downtown office and bravely asked to see a doctor. I was ushered into the exam room of a very nice woman doctor, another thing I had only seen on TV. I cringed through my first pelvic exam, even though the nice doctor complimented me on my “textbook cervix.” When my legs were back together and on the ground, the doctor handed me a prescription that read “To regulate flow” and told me to come back in a year.

I had drugs and Michael and his empty house and no more worries about being knocked up. It was a fun summer. I tried to be mindful of the time on my work day when I had to punch in at The Bellows at four to make sure that those idiots who showed up for a steak dinner at five would have a fresh crisp salad. But we were insatiable. One afternoon, as I felt Michael poking me in the leg, ready for a third bout, I raised my kiss-swollen face up off the bed and saw to my horror that it was a quarter to four. Michael was pulling me down; of course he didn’t understand why I had to be at The Bellows on time. Unlike everyone else I knew, Michael did not have a summer job. He refused on principle to work for the man. “Who cares if you’re a few minutes late?” he grumbled. “It’s not like you’re doing anything important.”

The real German, I was determined to keep the salads running on time. I threw on my clothes, not bothering to wash. Michael grudgingly offered to walk me the ten minutes down to The Bellows. Walk? I need to go at a quick trot to get there on time.

I was two blocks away from the restaurant, waiting at the corner to cross the busy-for-Duluth Superior Street. Traffic finally slowed as a bus pulled up and stopped. I started to dash across the street, certain Michael was beside me. But he had seen the car behind the bus veer left to go around it. I did not. I felt a bang and landed on the hood of a cab, looking into the horrified face of the driver. The next thing I knew I was on the ground and Michael was standing over me, red-faced and sobbing, as the bus driver and the cab driver both shot out of their vehicles. I assured everyone I was fine, and got up to continue on to work. No one was going to let that happen; I was guided over to the curb by several hands and forced to sit. Soon an ambulance showed up, and even though I was still protesting — who would make the salads and defrost the shrimp? — I was loaded inside. Before they shut me in, I called over Michael, who bent over me for my last words, which were to call The Bellows and explain that I had been hit by a car.

At St. Luke’s Hospital I was X-rayed and palpitated and asked if I knew the name of the president and what day of the week it was. I did, and nothing was broken; when my father showed up (who had called him?) they were ready to release me. I pulled my jeans on over the yellow and purple bruise that covered my left leg from knee to hip, pushed myself off the examination table and fell over. I could not put any weight on that leg.

My father drove me home in silence, then helped me onto the living room couch, the first time he been in the house since the day he left. He stayed until my mother finally bustled in, furious at having been summoned home by some stupid kid thing, and even angrier that my dad got to act the part of the responsible parent. As soon as he was gone, she lit in to me: how in the world does anyone get hit by a car? Couldn’t I see it coming? She was also suspicious of where I had been all that afternoon; it was July, I was not doing homework at Michael’s house.

In a few days I had recovered enough to lean against the big stainless steel sink at The Bellows, peeling shrimp and cracking oysters; and to figure out ways to make love on Michael’s narrow bed without his weight, however slight, on my injured thigh. Michael kissed the bruises, fading into less corpse-like shades, and told me how sorry he was, how he had just been about to warn me when I went teacups over kettles on the hood of the taxi. He did not feel badly enough to go out and look for a job himself; I kept working and kept spending my paycheck on drugs.

Summer ended and that golden age of youth, senior year, started. Saturdays were still reserved for Michael and acid, but every Friday I was with my friends in the White Delight, cruising up and down Duluth, in search of where the action was. Our senior year parties became wilder, more abandoned, with more booze, more drugs, and dozens of kids in various stages of intoxication. We huddled around house-sized bonfires on the lake shore, tossing empties into the flames and laughing hysterically at nothing. We smashed into the Anderson’s basement; the crescendo of “Stairway to Heaven,” still new to our ears, made conversation impossible and unnecessary.

There were a few casualties. Betsy James had a fight with her boyfriend, and took off on his motorcycle; he found her a block away pinned under it, with a broken leg and a large patch of her skin left on the asphalt. Craig Whiteman, one of East’s few greasers, polished off a six-pack of Grain Belt at a party and accepted a dare to break into old lady Congdon’s mansion. No one knew that Dorothy Congdon was a champion skeet shooter who slept with a loaded shotgun beside her.

My band of sisters grew closer together as high school graduation neared. We had forged a sacred bond, at a time when our hearts and souls were soft and malleable, and our feelings strong and blood hot. Our friendship was built on years sharing our teenage loves and disappointments, laughing, drinking, sometimes crying, and always caring deeply. We knew that college and jobs, new lovers and new friends, would soon disrupt the centrifugal force that kept us together, though we vowed not to let that happen.

Michael and I also believed with the fervor of a religion that we were destined to be forever together, the fever dream of first love. But while I had despaired every time my period was half a day late, Michael romanticized the possibility of us having a baby. He longed for an addition to his tiny two-person family and got all misty-eyed listening to Crosby, Stills, and Young’s “Our House.” We shared a dream of a small apartment in Minneapolis, filled with sex and drugs, college textbooks and cats, where we would fall asleep in each others’ arms, but my dream definitely did not include a baby.

While my heart was sworn to Michael, the rest of me was stirring with other desires. Being safely on the Pill turned a key in my mind, which opened up a new world of sexual possibilities. Emily Dickinson wrote “There is no frigate like a book, To take us miles away,” and for years books had been my only escape from my stolid small town life and boring middle-class family. I could get lost again and again in the exploits of Bilbo Baggins and Gandalf, Arthur and Merlin, Dorothy and Alice, and all those other plucky young heroines. Then I discovered that drugs could shanghai my mind, transport me to different realms. Now I realized that there was another vehicle that could take me away on adventures: my own body.

I started looking at other boys with a hungry curiosity. What would it be like having sex with them? How would they smell, how would they touch me? Would the sex be better or just different? And maybe just different would be exciting enough. According to Time magazine, which still made its weekly appearance in our mailbox, the sexual revolution was in full swing. I was a willing recruit to any revolt. Even my own mother, still pretty at thirty-seven and post-divorce slim, had seduced a former stalwart of the Catholic Church and father of six, and was busy trying to get him to dump his wife and marry her.

The culture, my body and mind, and the nice people at Planned Parenthood were all encouraging me to expand my sexual horizons; the only reason not to was that Michael, my sensitive, moody lover, would be hurt. So I never told him about the others. I was callow and callous, and from a distance of many years, I can see that I was not the adventuress I thought I was — just an asshole.

There was Jonathan, who had been making me laugh since seventh grade advanced math. He was a behind-the-scenes stagehand for all our aspirational high school plays, painting flats, adjusting the lights, and cracking up everyone in earshot. The plays our high school put on were ancient chestnuts, chosen for their ability not to offend anyone: starting with “My Three Angels” (misspelled on every poster as “My Three Angles”), about a trio of fugitives from Devil’s Island, through “You Can’t Take It With You,” with its cast of thousands.

That play provided my one chance for glory on the stage. I had been trying out in vain for a part in one of East’s plays since I was a sophomore. Our creepy drama teacher Mr. Canfeld had given every single leading role for the past three years to milquetoast Grace Myers; rumor had it that she let him feel her up. On my ninth audition for him, Mr. Canfeld felt sorry for me, ignored my lack of acting ability, and cast me as Olga, the White Russian countess, who shows up in the final act to deliver her three lines. After our second and closing performance, cast and crew gathered in somebody’s parent-less house for one of the epic theater parties. Drunk and high, Jonathan and I were talking, then giggling like lunatics, then kissing. We locked ourselves in a bathroom so we could take some of our clothes off. As I had hoped, it was different and it was fun, like taking a roller coaster ride together. Miraculously, Jonathan and I became better friends.

One sub-zero Saturday night, Michael Vlasdic and Needle both sick with the flu, Roger and I ended up alone, driving aimlessly around Duluth in search of a party. Sitting next to him on the front seat, like boyfriend and girlfriend, I realized I liked his craggy profile and scooted over a little closer, feeling a pleasurable tingling. When Roger put his arm around me, a bolt shot through my body to where his hand rested on my shoulder; we both felt the electricity through our winter woolens. Without saying a word, Roger steered for Skyline Drive, the favorite parking place for Duluth teens. We stretched out as much as we could in the back seat and committed our double betrayal, he of his friend, me of my soulmate. When we were done, we felt a bit bad and swore it could never happen again. But it did, and it was furtive and secret and thrilling.

I had always had a little crush on handsome, sleepy-eyed Jack France, who showed up occasionally at Open Mind meetings to read his angsty poetry. He was like me, a flitter among groups, a smart athlete who got high. Now I side-eyed him in Mr. Burrows’ class, where he sat alone in the back, gazing out the window. I wondered what it would be like to kiss him.

I found out on a yellow Bluebird bus making its bumpy way back from Telemark, Wisconsin, after a day of spring skiing. Nancy Erman had organized a school ski trip, one of the last hurrahs of our senior year. We skied stripped down to sweaters and blue jeans, luxuriating in the sunshine that was almost warm. There was such joy in the day, in our forever young bodies that we sent hurling recklessly down the slopes, again and again, until the lifts slowed and stopped and it was time to go home. Jack and I had skied together that day, and it didn’t take much wrangling on my part to end up sitting next to him on the tot-sized school bus seat. Jack shook out a package of Lucky Strikes from his pocket and lit a cigarette. Then we kissed. I thought I was the world’s best, most experienced seventeen-year-old kisser; I was knocked for a loop. Jack’s kisses shrunk the entire world down to the two of us, nothing but slightly chapped lips and gentle exploring tongues and the taste and smell of tobacco which reminded me of fall’s burning leaves. On the bus, in parkas and long johns and snow-soaked Levi’s, there was nothing more we could do than kiss, and the kisses were everything.

Jack and I never went any further. For years, every time we ran into each other, Jack and I would end up in dark corners where we shared those deep soulful kisses, sometimes for hours, until he took off one autumn on a solo cross-country bike trip to Seattle, where he leapt off the George Washington Memorial Bridge.

Being with Jonathan, Roger, and Jack was fun, it was sex with no agenda, no strings attached. It wasn’t about love, or negotiating a relationship, or even about my desperate desire to be thought of as pretty and sexy and cool.

I was beginning to regret the plans that Michael and I had made, that we’d go off together to the University of Minnesota in Minneapolis and live happily ever after. I was going to spend my first year in a dorm; he would stay with a friend of his mother’s who had offered him almost free rent and board. Eventually we would find an apartment and move in together. In the pleasant mist of these daydreams, I didn’t think about how we would pay the rent; his mother had no money, I knew neither of my parents would subsidize my living in sin, and Michael had never shown the slightest desire to find a job. I had left the salad and the shrimp at The Bellows behind; my vast restaurant experience got me hired as a waitress at The Flamette, where despite my dropping a full glass pitcher of maple syrup my first day and my inability to carry more than two plates at a time, I was making enough to buy drugs and squirrel away some spending money for college.

East High had no guidance counselors to talk to about universities; the only adult who had spoken to me about college was my grandmother, who offered to pay my tuition if I went to St. Scholastica, a Catholic woman’s school right there in Duluth. No thank you.

I filled out the application for the University of Minnesota, wrote the essay, tore out and filled in a check for $15 from my mother’s checkbook (she had finally gotten her own bank account), and sent the package off to Minneapolis, never doubting that I would get in and never considering applying to any other schools. The housing catalog that came with my acceptance letter featured a brand new, co-ed dorm, the only dorm that allowed 24-hour visitation from the opposite sex — as long as you had your parents’ permission. I checked the box for Middlebrook Hall on my housing form, forged my mom’s name on the permission slip, and fell into a fantasy of unlimited sex with unlimited college boys, with an occasional guest appearance by Michael Vlasdic.

For once the reality matched the daydream. My perky, adorable, All-American college roommate, Nancy Lowe, went back to her suburban home every weekend to work at the local pizza place and have sex with her own boyfriend, leaving me a wonderfully empty dorm room for entertaining. I was sandwiched between boys; at Middlebrook Hall the sexes alternated floors. My new friend Liz Hepper, who I had met in her dorm room closet, where she was chugging a bottle of Southern Comfort, introduced me to a herd of funny, smart boys from her hometown of Rochester, including a pharmacy major who had very good drugs. There were so many boys in my dorm, and they were all so interesting and cute. And out on the huge campus there were 20,000 more, surrounding me in class, eating dinner in the cafeteria, napping or reading or throwing Frisbees on the still-green campus lawns.

Despite all our plans, despite my absent roommate and the 24-hour visitation, despite how much I thought I looked forward to the first time I could sleep with him, entwined and spooned and inhaling his sweet spicy scent, Michael and I never spent a single night in my skinny dorm bed.

Before the first week of college was out, I called Michael and broke up with him, in the worst way possible, over the phone.

There was another important phone call that first month of my freshman year. My mother called to tell me that she was moving to Colorado Springs. She did not tell me that she was moving in pursuit of the ex-Catholic father of six, who had finally left his wife; he had also left Duluth to live on a small ranch in Colorado. I was instructed to come back home that weekend to box up anything I did not want sold or thrown out; my mother and sisters were downsizing from a six-bedroom stately home to a two-bedroom apartment.

I wandered through 101 Hawthorne, most of the rooms already empty of furniture. Almost everything was gone from my old bedroom, where I had spent so many nights tripping, transfixed by the golden glow from the streetlight streaming through the trees. A few summer clothes hung in my closet; I put them in my suitcase, looking forward to catching some boy’s eye in my cute Indian-print sundress in the spring.

I went back down to the TV room, where our bookshelves were, and where two large cardboard boxes sat gaping. “Put what you want to keep in one,” said my mother. I pulled from the shelves the books that had been my youthful frigates: Alice’s Adventures, the Tennile drawings only slightly defaced from Crayolas wielded by my sister Lani. The Wizard of Oz. The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe. The Fairy Tales of Hans Christian Anderson, minus “The Little Mermaid” and “The Little Match Girl.” I opened up the books Michael had given me, The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings trilogy, each frontispiece signed “I love you” illustrated by his round smiling face. My heart gave a small twist as I stowed them in the moving box. Next came the never-paid-for plays of William Shakespeare, three heavy tomes, The Histories barely cracked. I added The Guide to Minnesota Fauna and Flora, which had been handed to me by the outdoorsy old lesbian who had dragged me around Duluth’s fields and woods. Here was Angelique and the Sultan, with steamy seduction scenes on every page, never returned to Kathy O’Dell. A ragged paperback sci-fi novel, The Blind Spot, that I had read three times in a row, on that trip to Mexico, lacking any other English-language reading material that was not dental-related. And of course the fruit of my junior year with Mr. Burrows, the two volumes of American history and literature, typed out night after night, with my name printed on the spine in gilt letters.

I sealed my cherished books up in a moving box and told my mother that was all I wanted shipped to Colorado. That Christmas break, in my mom’s ticky-tacky Colorado Springs apartment, I sat in the living room, hemmed in by our old furniture: the mahogany dining table for six, the gold and cream French Provincial sofa and matching end tables, and the immense cabinet TV. I opened a cardboard box identified as “Gay’s Books” in black marker. It contained stained Junior League cookbooks, several years of Reader’s Digest Condensed Books, a collection of Harold Robbins paperbacks, a single addendum to the World Book, dated 1960, and a battered Webster’s dictionary. My childhood was gone.

North Country Girl: Chapter 29 — A Teenager in Love

For more about Gay Haubner’s life in the North Country, read the other chapters in her serialized memoir. The Post will publish a new segment each week.

My first date with Michael Vlasdic had a few glitches. Duluth teen culture was car culture. With your friends a car was a party on wheels. With a boy a car was a bubble of privacy, a place to make out, WEBC on low, heater on high, the windows opaque with steam. I, however, had only a learner’s permit; to get that required just a multiple-choice test on road rules, the kind of test I aced every time. I had barely squeaked through drivers’ ed, the instructor constantly taking over control and slamming on his brakes because I was unable to gauge distances between the car I was driving and everything else, other cars, pedestrians, curbs. I also had difficulties telling the brake pedal from the gas pedal. My sweating, pale instructor assured me that all I needed was more practice, but every time my mother let me take the wheel it ended quickly in shouts and tears. I was idiotically optimistic that when I took the road test in December, when I turned sixteen, I would magically pass, but for now taking the family car was verboten.

Michael Vlasdic lacked both a car and a father. His mother was originally from Latvia

(a country I knew only from volume L of my old World Book encyclopedia, which identified it as one of the Soviet Socialist Republics) and had moved to Duluth to teach German at the university. She was stately and Old World polite, with a solid-looking helmet of dark hair, and always in a boxy wooly suit, thick beige nylons, and sensible shoes. The missing deadbeat dad was in Mitchell, South Dakota; Michael once proudly showed me a postcard of a large yellow structure that proclaimed Greetings from the Corn Palace! that his dad had sent him. In lieu of money, I guess.

I had met a few kids without fathers, but a family without a car? Where could Michael and I go on our first date? You could not enter the London Inn parking lot on foot. You’d be a laughingstock.

On the phone Michael said, “Why don’t you come over here and we’ll listen to records?” I did not have a better idea, so that Saturday I walked the twenty minutes over to Michael’s house. His mother was out for the night. His mother was out a lot.

Michael and his mother lived in a small up-and-down duplex filled with books and cracked oil paintings in gilded frames, dark heavy furniture, more books, jewel-toned oriental rugs, potted plants, and more books. There was also the standard big cabinet hi-fi in the living room. Since there was no parent in the house, Michael and I went to his room to listen to music and so Michael could smoke a joint, which he did leaning precariously out the window. He offered me a hit, but I was afraid if I had my usual pot-induced coughing fit while straddling the windowsill I would plummet to the ground and that would be a hell of a first date.

We started talking, about music (we liked the same bands! Of course in 1969 every kid was devoted to Steppenwolf, Cream, Jimi Hendrix) then books (Michael had read The Lord of the Rings three times to my twice). A current of tingly magnetism drew us closer and closer together, and then there was a lot of kissing. Seated kissing, with our arms propped straight as crutches on Michael’s narrow, neatly-made bed, then lying down kissing, with arms wrapped around each other, bodies close enough together that I could feel him harden. Michael reddened with embarrassment, got up to take off his glasses, and we kissed some more.

Time played its elastic tricks: it stopped while we were kissing, then hurried forward, the clock rushing to eleven, my curfew, and I had to leave, with still the twenty minutes to walk home. Michael and I untangled, he found his glasses, but it was impossible for us to part. He walked me back to my house, through the still and silent streets, a thousand stars on a moonless Minnesota night twinkling down at the new lovers. Michael was bookish and shy, a proto-hippie like me, and charmingly unaware of how good-looking he was. On that walk we shared what secrets and history sixteen- and fifteen-year-olds could have accumulated. We marveled that the universe had contrived to bring us together, two pieces fitting into place in the cosmic jigsaw.

We kissed as long as possible in front of my house; I was just beginning to put the horrors of July 21st behind me. If my mother should have appeared in the doorway and started yelling, I felt I would die. I pushed Michael away, slipped into my sleeping house and floated up the stairs. In bed, I wrapped my arms around myself, imagining it was Michael who held me, I thought of the dirty books hidden away underneath me; the pages I had carefully dog-eared didn’t begin to describe the sweet ache I felt, a longing I knew Michael felt too. I wondered how long it would take us to go all the way.

It took a week. The following Saturday, up in his room, his mother attending another university faculty beanfest, our clothes half off and “Whole Lotta Love” urging us on, Michael told me he loved me. “I love you too,” I said, and it turned out those really were magic words, words that made it imperative that we get rid of the rest of our clothing immediately. It was Michael’s first time and I wished it were mine too. “Making love” and “having sex,” are such awful phrases for what we did. We were two young animals, playful, tender, funny, considerate, with wildly responsive teen-age bodies we smashed together as closely as possible. It was as if the two of us had invented sex, sex that was as transcendent and addictive as any drug.\

Adorable, innocent Michael did not have a condom, since he was even more unwilling than I was to go into a drugstore and ask for a package of rubbers, which in those days were kept locked up on a high shelf in the back of the storage room to extend the embarrassment of the foot-shuffling, eye-averting teenage boy waiting at the counter. (One particular wisenheimer druggist liked to yell out, “What size, buddy?”)

After our first time, I called an emergency sex consultation with my girlfriends, held in Linda Laurence’s basement. While taking sips from Linda’s parents’ collection of Bols after-dinner drinks (crème de menthe, crème de cocao, peach brandy, cherry kirsch, and other stomach-churning flavors) and everyone but me smoking cigarettes, we discussed how I could have as much sex as possible without getting pregnant. Alternative methods were suggested and met with peals of laughter, some real, some forced; these ideas were quickly discarded. Some of my gang did have boyfriends who braved the druggist’s stink-eye and the wait of shame at the Tru-Value Pharmacy, but you don’t ask your boyfriend if he can spare a rubber so some other guy can get laid.

We pooled our collective knowledge and misinformation about the female reproductive system. Linda plucked a calendar off the wall and we huddled over it, guessing at those days that might be safe and days I should definitely keep my panties on.

Pregnancy was the dark looming cloud that hung over rapturous teenage sex: everyone knew of the senior girl who had been sent off to a home for unwed mothers, returning after six months thin and wan and without a baby or a boyfriend. But despite regular scares, no one in our gang got pregnant or had any tragedy befall us. While we had scrapes and accidents, heartaches and breakups, for the three years of high school we lived in a teen fairyland, where we could have sex and not get pregnant, drive drunk in cars with no seatbelts without going through the windshield, and hop on and off moving freight trains without losing a leg.

Besides being considerate enough to go out almost every Saturday night, Mrs. Vlasdic thoughtfully taught class two afternoons a week. If it were the right day of the month Michael and I would dash from school to his house for the world’s quickest quickie. When Mrs. Vlasdic walked through the door at four o’clock, she’d find Michael and me at the dining table, fully clothed, surrounded by homework, and drinking tea. She had to have known what was going on.

My own parents had briefly met Michael and felt no reason to be alarmed: his mother was a university professor and Michael seemed too painfully shy and nerdish to be any threat to my already sullied honor. And at that point, my family was spinning apart.

After buying the big, impressive Hawthorne Road house, my dad spent less and less time there. My mom was taking a full-course load at the university, her youthful dreams of being an actress whittled down to a prospective career as a speech therapist. My younger sisters Heidi and Lani would have been latchkey kids, except we never locked our doors in Duluth; after school they walked the three blocks home together, let themselves in, and headed straight for the TV.

But even at its emptiest, my house was firmly off-limits for sex. I was haunted by the horrifying memory of Doug Figge trying to cover his balls with his hands, like Adam suddenly aware and ashamed of his nakedness. I wouldn’t feel safe having sex in my own home if both my parents were in Idaho.

On the Saturday nights Mrs. Vlasdic selfishly stayed home, we hopped in a car driven by Roger or Needle, Michael and I clutched together smooching in the back seat. We’d drive around Duluth for hours, the guys smoking pot or searching for someone to sell them pot.

I luxuriated in my membership in two high school groups: my gang of loyal, funny, raucous girlfriends, and the druggies of East High, whose numbers increased daily. We proclaimed our allegiance to the counterculture with long hair, fringed jackets, wire-rimmed glasses, beads, and bellbottoms. My pal Wendi Carlson became a fervent pot smoker and made it her life’s mission to teach me to inhale. She was even more disappointed than I was that I was still unable to draw the tiniest puff inside my lungs.

A member of the druggies was cute Stan Lewis, a year behind me, who showed up at all the parties with weed. Stan and I would find each other at these parties and swap what little we knew about psychedelics. Could you really get high from morning glory seeds or nutmeg? What was the difference between LSD, mescaline, and psilocybin? When you’re tripping, do you need someone straight around in case you freak out? How much did these drugs cost and where could we get them? I thought of Joe Sloan, who would soon be back in Duluth for Christmas, which reminded me of Doug Figge and the astronaut, so I lied and told Stan I didn’t know anyone who had those kind of drugs.

Stan, a determined guy, went out and found someone who did, and for my sixteenth birthday he gave me a small blue pill that he said was mescaline, supposedly not as mind-blowing as LSD. He handed it to me in the parking lot of the London Inn. I immediately popped that pill in my mouth, washed it down with watery Coke, and thanked Stan with a friendly kiss on the cheek, which I now suspect was not what he was hoping for. I jumped into the White Delight on to Wendi Carlson’s lap and whispered in her ear what I had just done.

There were no empty houses that night so my sixteenth birthday celebration was a three-hour auto tour of residential Duluth with six of my best friends. It was early December, pre-broomball season, but there were frequent stops for peeing in the snow and return visits to the London Inn to see if any cute boys were around. Wendi kept pinching me hard and asking, “Are you tripping yet? How about now?” and I kept shaking my head no.

I was somewhere around Hawthorne Road, on the edge of my front lawn, when the drugs began to take hold. I was sober as Judge Erman when I climbed out of the White Delight and headed into my house; I had not a single drink on my birthday, waiting for the mescaline to kick in and transport my mind to Peter Max world.

Just as I was thinking that poor Stan had been swindled, I opened the door to my house and was blinded by the hot-as-the-sun kitchen lights. I stumbled and braced myself up on the wall, which was wildly tilting, while a galaxy of neon geometric shapes swirled around me. It took me a minute to realize that the low frequency rumble I was hearing was my mother asking me how my birthday was. I slid into the living room doorway and made small talk to the elongated monster with snakes for hands that was sitting on the TV couch. I finally escaped and made my way up to my room and tripped for hours, staring out into the night, where twinkling snowflakes and yellow streetlights and the deep blue of winter created a hypnotic tapestry. I twirled the dial of my melting bedside radio, WEBC having signed off for the night, searching for music and unfortunately hit on a horrible station out of Chicago that chose to play “D.O.A.” by Bloodrock at 2 a.m. I listened to the whole thing, perched on the edge of madness, switched the radio off, and hid under my blanket until I stopped hallucinating horrible, bloody car wrecks and finally fell asleep.

I couldn’t wait to trip again.