The 15 Best Motown Movie Moments

superThe Motown sound was radio gold, and it turned out to work well in movies too. Berry Gordy Jr.’s record label turned out soul, R&B, and funk hits that have been used to set the tone in a host of movie scenes over the years. When a Motown song plays in your favorite movie, it’s hard not to sing and dance along. Here are 15 of the most memorable Motown movie moments.

1. “Good Morning Heartache” by Diana Ross in Lady Sings the Blues

Uploaded to YouTube by Diana Ross

Diana Ross sings Billie Holiday’s famous song in Motown’s biopic of the legendary jazz singer. She was nominated for an Oscar, and the soundtrack repopularized Holiday’s music as it hit number one on the Billboard chart.

2. “It’s So Hard to Say Goodbye to Yesterday” by G.C. Cameron in Cooley High

Uploaded to YouTube by Boys II Men

G.C. Cameron’s version of the soul song didn’t make much of a splash upon release in 1975, but its use in the funeral scene of Cooley High made it a cultural touchstone. Many others sang “It’s So Hard to Say Goodbye to Yesterday” over the years as a goodbye song, and Boyz II Men made a radio hit out of it in 1991.

3. “Superstition” by Stevie Wonder in The Thing

Uploaded to YouTube by Stevie Wonder

It’s the perfect song to turn up (even when a recent gunshot victim is yelling to turn the music down), and it’s the perfect song for a foreboding scene hinting at a strange presence on an Antarctic research camp.

4. “Ain’t Too Proud to Beg” by The Temptations in The Big Chill

Uploaded to YouTube by The Temptations

Although its soundtrack is chock full of Motown hits, The Big Chill’s best musical moment comes as the group of friends finds solace in dancing to an old song during a difficult time. The song was included in American Film Institute’s “100 Years … 100 Songs” program in 2004.

5. “I Just Called to Say I Love You” by Stevie Wonder in The Woman in Red

Uploaded to YouTube by Steve Wonder / Universal Music Group

Stevie Wonder’s 1984 megahit was the best-selling Motown song ever in the U.K. Gene Wilder’s film “The Woman in Red” included other original Wonder songs, like “Love Light in Flight” and some duets with Dionne Warwick.

6. “The Tracks of My Tears” by The Miracles in Platoon

Uploaded to YouTube by Smokey Robinson – Topic / Atlantic Records

After serving in the U.S. Army in Vietnam, Oliver Stone wrote a script called Break that he struggled for decades to get made into a movie. When he was finally successful, the film Platoon was roundly praised for its realistic portrayal of the Vietnam War, both in terms of horrific combat and scenes like this one that show companionship wrought from the conflict.

7. “Nowhere to Run” by Martha and the Vandellas in Good Morning, Vietnam

Uploaded to YouTube by Martha Reeves & The Vandellas – Topic / Universal Music Group

Robin Williams’ kooky performance as an Army radio deejay during the Vietnam War earned him his first Oscar nomination. The movie’s soundtrack is a spirited list of ’60s pop music, and it includes Martha and the Vandellas’ hit “Nowhere to Run.”

8. “Do You Love Me” by The Contours in Dirty Dancing

Uploaded to YouTube by The Contours / Universal Music Group

Baby Houseman gets her first taste of dirty dancing, watermelon in hand, at a secret staff party in the Catskills. The Contours were an early Motown success, and Dirty Dancing renewed their popularity in 1987.

9. “Ball of Confusion” by The Temptations in Sister Act 2: Back in the Habit

Uploaded to YouTube by The Temptations / Universal Music Group

Whoopi Goldberg trains a choir of nuns to perform Motown hits in Sister Act. In the sequel, they’re seasoned soul sisters with a heavenly Temptations routine that more than does the song justice. Kathy Najimy and Mary Wickes are comedy gold.

10. “Baby Love” by Diana Ross and the Supremes in Jackie Brown

Uploaded to YouTube by The Supremes / Believe SAS

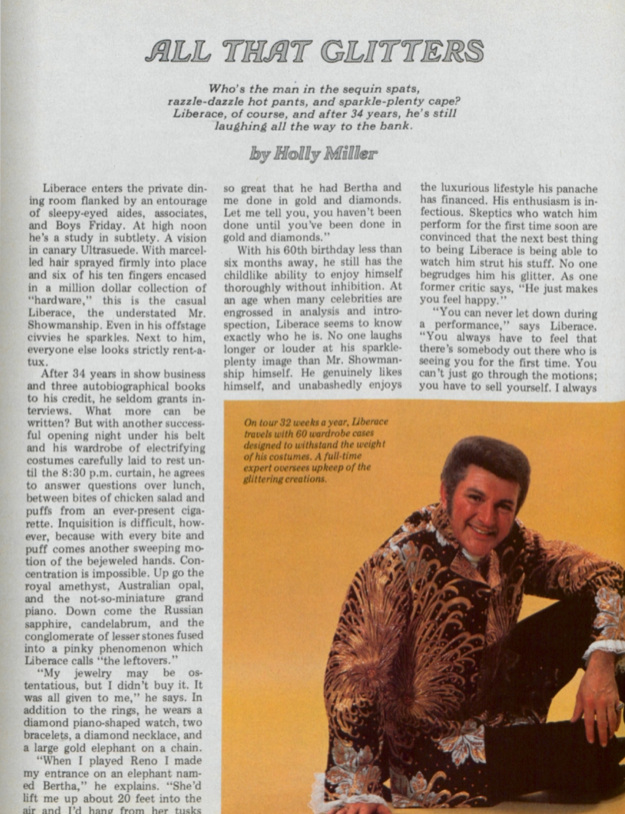

Quentin Tarantino’s love of funk and soul music is on display in this 1997 tribute to blaxploitation films. Hattie Winston serenades an aloof Robert De Niro with a classic Supremes song in full royal blue sparkling garb in a short but memorable scene.

11. “Machine Gun” by The Commodores in Boogie Nights

Uploaded to YouTube by The Commodores / Universal Music Group

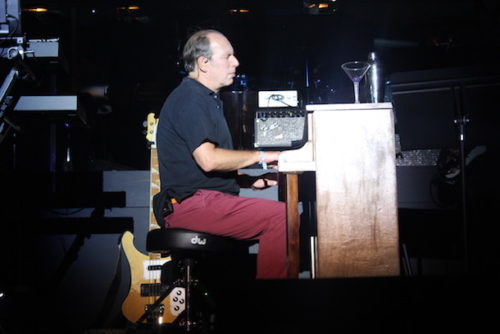

The Commodores’s dynamite clavinet instrumental was used widely as a theme in the 1970s and 80s (as well as Beastie Boys’s “Hey Ladies”). Porn star Dirk Diggler shows off his disco moves in his new platform shoes to the song in Paul Thomas Anderson’s chaotic Boogie Nights.

12. “Ain’t No Mountain High Enough” by Marvin Gaye and Tammi Terrell in Stepmom

Uploaded to YouTube by Movieclips

The 1999 drama about a family being ripped apart and mended back together uses one of Motown’s best duets. As a woman who has just received a cancer diagnosis along with news that her ex-husband will remarry soon, Jackie reconnects with her children by lip syncing Marvin Gaye’s and Tammi Terrell’s hit.

13. “Let’s Get It On” by Marvin Gaye in High Fidelity

Uploaded to YouTube by Marvin Gaye / Universal Music Group

In his breakout film role, Jack Black sings Marvin Gaye’s sensual masterpiece “Let’s Get It On.” The song has been used in countless commercials and movies to set a sexy tone, but never was it sung quite like it was by the Tenacious D frontman.

14. “Super Freak” by Rick James in Little Miss Sunshine

Uploaded to YouTube by Movieclips

Unbeknownst to the rest of their family, junior beauty pageant hopeful Olive and her grandfather prepare a dance routine to Rick James’s risqué funk hit about a “very kinky girl” that you “don’t take home to mother.”

15. “I Want You Back” by Jackson 5 in Guardians of the Galaxy

i

Uploaded to YouTube by The Jackson 5 – Topic / Universal Music Group

The old school soundtracks of the popular Marvel franchise feature several Motown hits, but the most iconic among them is perhaps “I Want You Back,” playing to a dancing Baby Groot in his adorable resurrection scene.

Featured image: Shutterstock

Wit’s End: They’ve Turned the Soundtrack of My Youth into Muzak

Read more from Maya Sinha’s column, Wit’s End.

I was in a department store, shopping for items the Victorians called “unmentionables,” when a 1992 song from the British band The Cure began to play.

From hidden speakers, under the bright retail lights, lead vocalist Robert Smith — a pale Goth in eyeliner, lipstick, and a tangle of ink-black hair — sang the opening bars of “Friday I’m in Love.”

This song was deeply familiar from my high school and college years. Back then, Smith was a romantic figure: a moody, sensitive rebel who fronted an alt-rock band. Though he strove to look three-quarters dead, he would not be caught dead in the women’s underwear section of the flagship store in a suburban mall.

Yet here he was in 2020. A wave of cognitive dissonance crashed over me. Why was the store piping in The Cure, a poignant reminder of my vanished youth? Was nothing sacred?

For Americans born between 1965 and 1980, the generation known as Gen X, this is now a common experience while shopping. We select lettuce from a superstore crisper to the rapturous vocals of Belinda Carlisle in “Heaven Is a Place on Earth” (1987). We try on sensible shoes to the late Dolores O’Riordan of the Cranberries singing “Linger” (1993). Checking our tween into the orthodontist’s office, we’re assailed with INXS’s darkly urgent “Devil Inside” (1987) or REO Speedwagon’s earnest “Keep On Loving You” (1980). We gas up our SUVs to the sound of giddy infatuation in Sting’s “Every Little Thing She Does is Magic” (1981).

Decades later, these 1980s and 1990s pop songs still pack a wallop. In a recent essay, Gen X writer Meghan Daum wrote that she’s stopped listening to four decades of pop music, songs that evoke so many bittersweet memories that she now avoids them “as if avoiding pain.”

These one-time radio hits are powerfully evocative, Daum writes, because music “embeds itself into our emotions, often burrowing far deeper than the memories of the events that spurred those emotions. From there, the songs we love become the half-life of our emotions. They are whatever’s left of whatever was going on at the time.”

For people in their 40s and 50s, pop songs conjure memories of childhood, junior high, high school, summers, friends, significant others, college, jobs, holidays, weddings, divorces, and family events. Just little things like that. No biggie.

But if you’re trying to avoid the pain (or mixed feelings) these songs evoke, too bad: The hits of 1980-1999 are playing on continuous loop at the grocery store, a cavernous building you disconsolately roam four times a week. Good luck buying organic peanut butter without crying, Mom! Have fun picking out dog food while tears of regret and forever-lost chances burn your eyes!

The cruel irony of listening to bouncy pop songs from junior year while tossing headache medicine and nutritional supplements called Change-O-Life into the shopping cart is apparently lost on the corporate overlords who devised this torture. Why have they done this, desecrating our memories by canning our music?

Piping music into public spaces was the brainchild of U.S. Army Major General George O. Squier, a renowned inventor who devised a means of playing phonograph records over electric power lines. In 1934, after radio took off, Squier founded the Muzak Corporation, which piped commercial-free music into hotels and restaurants. “The music itself was newly recorded versions of popular songs, but now produced with purposefully mellow, orchestral arrangements,” historian Peter Blecha wrote in 2012.

Research in the 1940s showed that music could influence behavior, and during World War II, Muzak was used to motivate factory and military workers. In the postwar years, the goal shifted to keeping customers in stores, with “soothing, saccharine sounds being pumped into dentists’ offices, grocery stores, airports, and shopping malls all across the nation and overseas,” Blecha explains.

On their journey to the moon in 1969, Apollo 11 astronauts calmed themselves by listening to Muzak. Back on Earth, however, soporific versions of hit songs became known as “elevator music.” In 2011, Mood Media announced that it had acquired Muzak for $345 million, adding to its portfolio of commercial music services for retailers, hotels, restaurants, gyms, and banks. Now supplying music for 470,000 commercial locations around the globe, the company was “delivering unique experiences to millions of people daily.”

Suddenly, elevator music was out; nostalgic pop playlists were in.

In 2020, music still affects shoppers’ moods, but not necessarily in a good way. We Gen Xers feel vaguely insulted when the soundtracks of our youth are cynically used to sell us things. We are this close to buying everything we need online, having it delivered by drones, and listening to our 1980s playlists when we want to, how we want to, in our own homes!

Retailers should take a page from video game designers, who similarly want to keep players engaged for as long as possible. The Legend of Zelda games have gorgeous, critically acclaimed soundtracks, setting the bar for ambient music that’s enjoyable for people of all ages. Why can’t we have original mood music in stores? (Attention, composition majors! A nation turns its lonely eyes to you.)

Until that day, I’ll have to listen to The Cure while going about my mundane errands, draining the music of all meaning. It makes me want to protest in some small but visible way, perhaps by wearing head-to-toe black, dying my hair with shoe polish, and piercing my earlobe with a nail.

By the time I get out of a store that’s recycled my memories to sell toothpaste and dish soap, I’m feeling a little Goth myself.

Featured image: Robert Smith of The Cure, 1985 (AF archive / Alamy Stock Photo)

We Are the World: 10 Things You Didn’t Know

The 1985 American Music Awards made history for a few reasons. Lionel Richie won six awards, Prince took home three, and Michael Jackson was shut out. But that was just the opening act. Later that night, Richie, Jackson, and a number of other artists finished cutting a record that turned out to be a massive worldwide hit while throwing a focus on a humanitarian crisis. Here are 10 things you didn’t know, or maybe didn’t remember, about “We Are the World.”

1. It Followed the Lead of Band Aid.

“Do They Know It’s Christmas?” by Band Aid at Live Aid (Uploaded to YouTube by Live Aid 1985

The first big charity single of the 80s was “Do They Know It’s Christmas?” Released under a supergroup named Band Aid that was organized by Bob Geldof (of The Boomtown Rats and star of the film Pink Floyd’s The Wall) and Midge Ure, the song featured members of U2, Wham!, Culture Club, Duran Duran, and a number of other stars from the UK. Geldof would perform on “We Are the World” as part of the chorus and later organize Live Aid and Live 8 with Ure.

2. Harry Belafonte Provided the American Spark.

Belafonte had the notion to put together a similar charity record using the biggest stars in America. Belafonte pitched the idea to music manager Ken Kragen, who took the idea to his clients, Kenny Rogers and Lionel Richie. They brought in Stevie Wonder and producer Quincy Jones. Jones recruited Michael Jackson. By then, the momentum was unstoppable.

3. Michael Jackson and Lionel Richie Did the Writing.

The official video for We Are the World. (Uploaded to YouTube by USAforAfricaVEVO)

To record a charity song … you have to have the song. Richie and Jackson teamed up, working on it for a week. Jackson took a version to Jones and Richie that included instrumentation and a chorus. They ended up reaching their final version of the song on January 21, 1985. Recording began the next day at Lion Share Recording Studio, which was owned by Rogers. The final night of vocals with soloists and the group chorus was set for the A&M Recording Studios in Hollywood after the AMAs when everyone would be in one place and would be more easily assembled and managed.

4. Prince Was Supposed to Be There.

While accounts vary as to why Prince ultimately wasn’t involved, the original plan had been to feature a section with he and Michael Jackson trading parts with each other. One story goes that Prince had to bail overzealous bodyguards out of jail after the AMAs, an event that was later parodied on Saturday Night Live in a sketch featuring Hulk Hogan and Mr. T as the bodyguards and Billy Crystal as Prince. Regardless, Prince and the Revolution did contribute a separate song to the We Are The World album, a number titled “4 the Tears in Your Eyes.”

5. And Madonna Wanted to Be.

For her part, Madonna was just making her commercial breakthrough, having just hit #1 for the first time with “Like A Virgin.” Jackson invited her, but her management advised her to decline because she’d have to cancel dates on her “Virgin Tour.” The thought was that, as a somewhat new artist with a big fresh hit, she needed to stick to the plan. It ended up working out for her, as her next single “Material Girl,” hit #2, and “Crazy for You” would replace “We Are the World” at #1 later in the spring.

6. One Sign Solved a lot of Problems.

When the artists began to gather, they found a sign on the studio door that read, “Check your egos at the door.” It was a funny and humbling reminder that the group was gathered for a larger purpose. It must have worked; while there were individual debates about how to sing certain parts or conferences over how to deliver certain lines, the group worked together all night, completing the song by the following morning.

7. The Cast Represented Multiple Generations.

The assembled array of talent was pretty incredible and spanned a number of genres, styles, and decades. Belafonte and Ray Charles were something of the elder statesmen. Jackson, Wonder, Smokey Robinson, and Diana Ross were among those that came up at Motown in the 60s and early 70s. Bob Dylan was, well, Bob Dylan. Bruce Springsteen, Steve Perry, and Lindsay Buckingham, among others, represented the rock side, for example, while Rogers, Willie Nelson, and Waylon Jennings brought in the country. In all, more than 45 voices are heard on the track, with 21 having identifiable solo bits. The wide net led to some genuinely thrilling, unique moments, as when Dylan and Charles sing together.

8. Why in the name of the Blues Brothers was Dan Aykroyd There?

The way that Aykroyd himself tells the story, it was purely by accident. Though Aykroyd did have a music background as “Elwood Blues,” one half of The Blues Brothers with the late John Belushi, he basically wound up at the recording session by happenstance. Aykroyd was looking for a money manager and spoke to a talent manager that asked him if he wanted to join the group. So he did.

9. The Impact Was Immediate.

The single, credited to USA for Africa, hit stores in March; the initial pressing of 800,000 copies sold out in days. The single would go on to sell 8 million in the U.S. The song and the album would generate more than $75 million toward famine relief. The song has been updated at various times and used for other purposes, such as relief in Haiti.

10. The Impact Continues.

Pink Floyd reunited with Roger Waters at Live 8 for global action against poverty. (Uploaded to YouTube by Pink Floyd)

The one-two punch of Band-Aid and USA for Africa provided the launch-pad for Geldof’s Live Aid, the first of the mega-charity concerts; held in London and Philadelphia, it was broadcast to nearly 2 billion people on July 13, 1985. The “World” session also gave Willie Nelson the idea for Farm Aid, the concert series aimed at helping farmers in America.

Remarkably, the “World” song and album still generate money for the charity today. It kickstarted a wave of charitable projects as well. The contemporaneous “Tears Are Not Enough” by a similar Canadian supergroup called Northern Lights (which included Bryan Adams, Neil Young, Joni Mitchell, Anne Murray, and Geddy Lee of Rush, among others) was also included on the album. The heavy metal community put together their own famine-relief record, Hear’n Aid, the following year; it featured artists like Ronnie James Dio and members of Judas Priest, Quiet Riot, Motley Crue, and more, while boasting an ensemble of lead guitarists in addition to the vocalists. A wave of further singles continued throughout the 80s, targeted at a variety of issues. “That’s What Friends Are For” by Wonder, Dionne Warwick, Elton John, and Gladys Knight was a #1 hit for AmFAR (American Federation for AIDS Research), while “Sun City” by Artists United Against Apartheid brought together artists from rock, rap, punk, jazz, funk, Latin, and world music to shine a light on the problems in South Africa. Charitable singles still abound, with the most recent high-visibility project being Lil Dicky’s star-filled “Earth” from 2019.

The Laziest Musical Instrument in the World

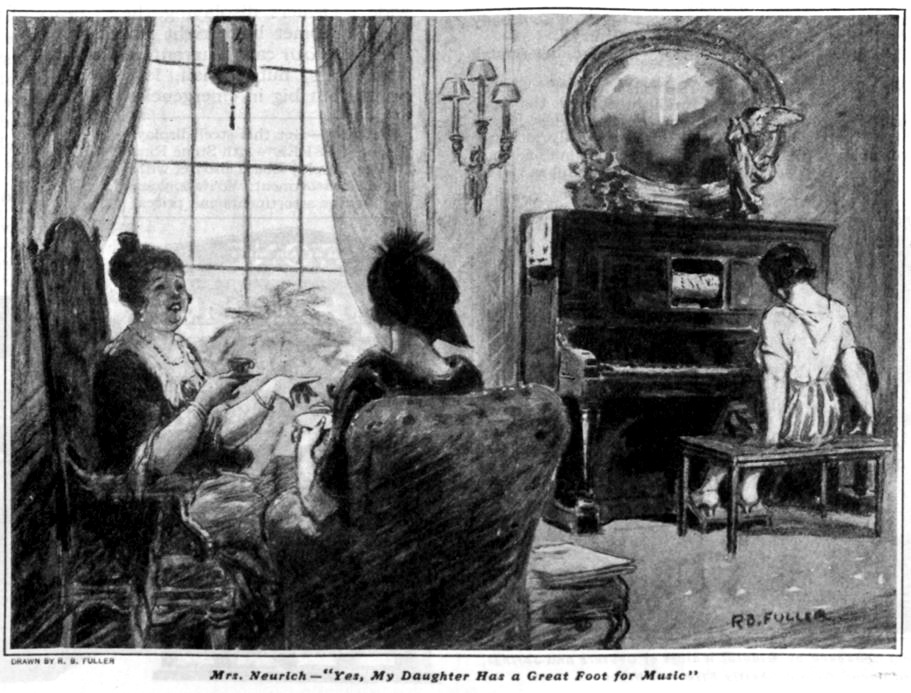

You’re an ambitious hostess in a turn-of-the-century, middle-class home. Your dinner guests have finished their mutton pies and cream pudding and they’re bouncing off the papered walls from the café noir. You’d planned to keep them entertained with some trendy parlor games, but charades isn’t going to cut it for this crowd. They need music, a group sing-along of “Sweet Adeline” or “Wait Till the Sun Shines Nellie,” but there isn’t a pianist in the bunch.

What’s a dilettante to do?

Enter the player piano. For the first time in history, attractive music filled homes without the need for a learned (human) player. With a steady pump of the foot pedals, or treadles, your piano could play itself, the black and white keys moving as if fingered by a poltergeist. Your dinner guests have a grand time and the party is saved, thanks to pneumatic technology.

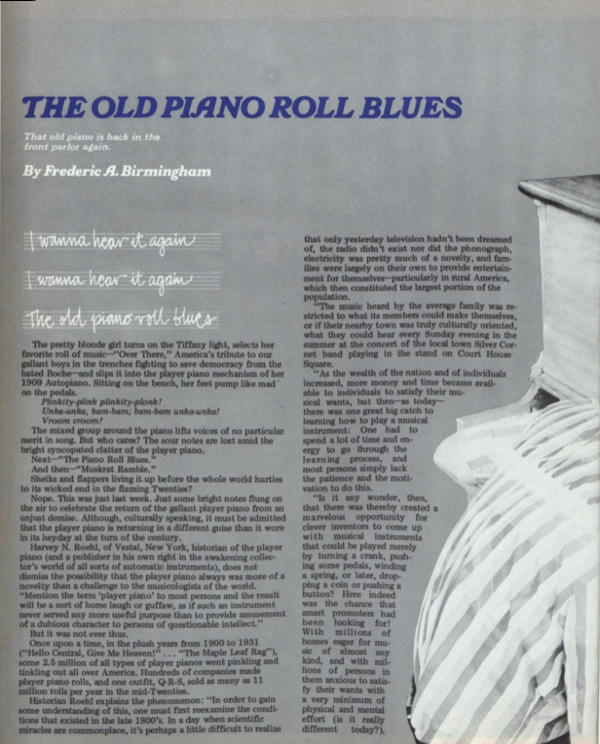

Though the player piano is understood now as an obsolete oddity — a short-lived steampunk quirk of simpler times — the instrument was a revolutionary step forward for bringing music into new places at the dawn of the 20th century. Piano rolls, the perforated “code” of the player piano, also remain as unique historical record of the stylings of iconic pianists of the period.

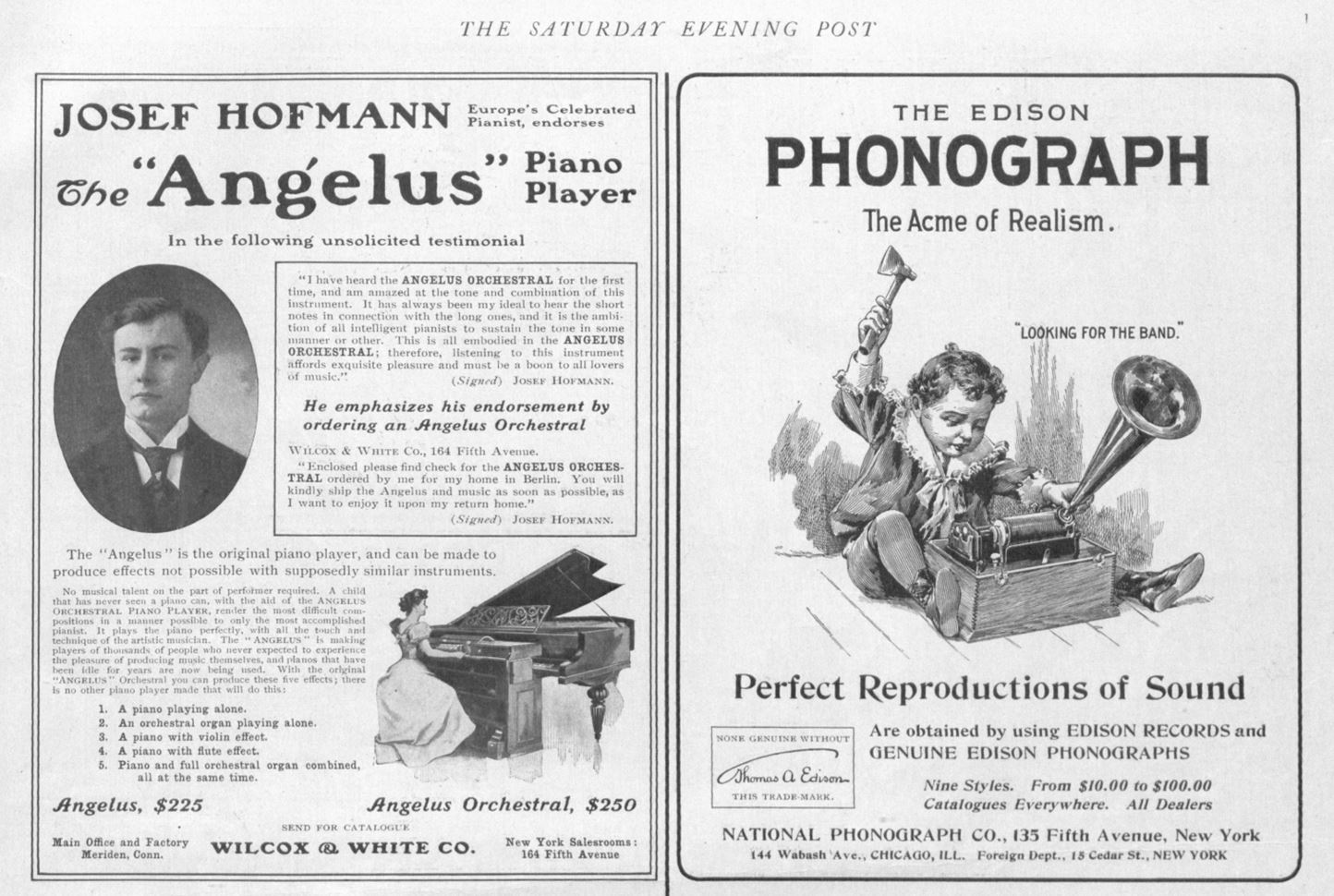

In 1901, piano manufacturers began advertising a contradictory claim in this magazine to anyone who ever longed for marches and ragtime music in their very own abode. The promise was that even the least practiced musical amateur could turn out perfect tunes with their new technology. At once, companies like Wilcox & White or The Cable Company insisted that there was “no musical talent on the part of the performer required” and yet “it enables you to play with the interpretation of the composer.”

So, which was it?

In reality, the operator did little more than power the musical device, adjusting its speed, as it rendered tunes from piano rolls in full splendor on the piano. It was live music — technically — but the “pianist” needn’t know the first thing about how to play. Before radios and record players increased music access to every corner of the country, the player piano brought professional music to consumers for a steeper price ($250 in 1905, equivalent to about $7,300 in 2019).

The first automated piano players were not the built-in models that instrument enthusiasts readily recognize today. They were an entirely separate piece of furniture, like the Angelus Orchestral, that the operator placed before their piano. These piano players (as opposed to player pianos) were developed and sold in the 1890s and in the first decade of the 1900s, and they played 65 keys instead of the full 88. Sitting behind the piano player and pressing a foot pedal or turning a crank would apply pressure to a bellows that runs a pneumatic motor — not unlike the early vacuum cleaners of the 19th century — and felt-tipped rods would strike down on the keys in accordance with the rolling paper guide.

Within a few years, manufacturers were moving the player mechanism into the piano, and the resulting streamlined instrument became more marketable. Historian Harvey Roehl said in this magazine in 1975, “As the wealth of the nation and of individuals increased, more money and time became available to individuals to satisfy their musical wants, but then — as today — there was one great big catch to learning how to play a musical instrument: One had to spend a lot of time and energy to go through the learning process, and most persons simply lack the patience and the motivation to do this.”

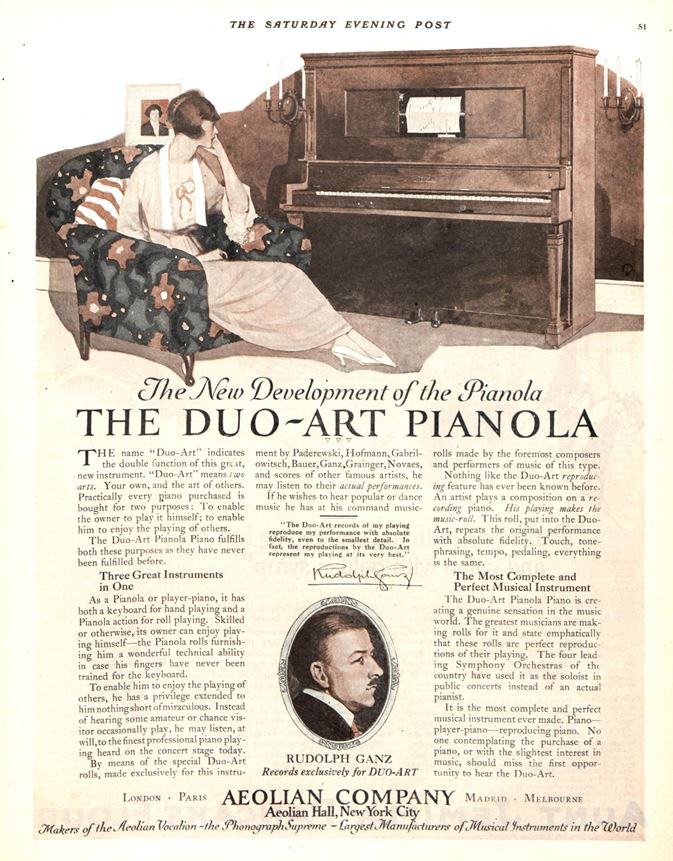

Dozens of companies began manufacturing player, or “reproducing,” pianos, but one company made its name synonymous with them: the Aeolian Company. Their product’s moniker — pianola — became interchangeable with player pianos in the years leading up to the first World War. In 1909, Aeolian claimed they had fought 17 infringements on their precious trademark, what Joseph Fox in American Heritage called “a piano and something more … a musical word for a musical object: quite perfect.”

Player pianos — especially the pianola — held full-page, color ads in the teens and twenties promising to “give your brains a holiday” or “hear Paderewski play his famous minuet” or even to aid in teaching your children music. Depending on who you asked, the mechanical piano was either a dismal metaphor for the decline of artistry or an exciting tool for democratizing the classics.

In Laurel and Hardy’s The Music Box (1932), the bumbling pair struggle to deliver a piano to a second-floor apartment, battling stairs, pulleys, and an unfortunately-located water feature. When they finally get the instrument to its rightful room, they discover it’s a player piano. The owner storms in, declares “they are mechanical blunderbusses!” and takes an axe to it, pausing to salute, of course, when the piano starts rolling the national anthem. In 1952, Kurt Vonnegut’s first novel, Player Piano, depicted the machine as a symbol of automation and dehumanization in an increasingly industrialized world.

It wasn’t only an apparatus for the unartistic, though. For some, the player piano gave way to a new kind of art: crafting impossible compositions.

Among the European creative scene in the 1920s that included James Joyce, Igor Stravinsky, Pablo Picasso, and Ernest Hemingway, New Jerseyan George Antheil gained a reputation as an enfant terrible of music. When he conceived his Ballet mécanique while living in an apartment above Shakespeare & Company in Paris, he called it “the first piece of music that has been composed OUT OF and FOR machines, ON EARTH.” The score called for 16 player pianos, xylophones, bass drums, a tam-tam, a siren, and three airplane propellers. Impossibly, the player pianos were all to be synchronized. Since this could only be done in theory, Anthiel settled for one player piano in live performances of his “ballet,” its keys emanating a futuristic cacophony more akin to Kraftwerk than Stravinsky. When he took his not-quite-realized performance to Carnegie Hall, the audience was nearly blown away by the propellers and he was laughed out of town.

Conlon Nancarrow, an offbeat musician and American expatriate, found the player piano in the 1930s, and he also saw it as a tool for taking his music beyond the confines of human capability. Nancarrow acquired a machine to cut his own piano rolls in the ’40s, and he used it to compose avant-garde music that defies the speed and dexterity of human hands. His compositions, like “Study for Player Piano No. 37” and “No. 40” sound like dueling pianos in some otherworldly cabaret — not exactly the kind of fodder for after-dinner sing-alongs.

As expected, most consumers weren’t using their player pianos to delve into the oeuvres of experimental sound. They wanted to keep up with popular musical trends and play ragtime and classical greats in their own home. Since the German Welte-Mignon company developed a machine that allowed pianists to record directly onto a piano roll in 1904, American companies competed fiercely to get the top performers into their offerings. Zez Confrey’s “Kitten on the Keys” was popular, as were rolls made by Percy Grainger and George Gershwin. Aeolian boasted that Josef Hofmann and Harold Bauer made rolls exclusively for the Duo-Art Pianola.

Millions of piano rolls were produced in the early century, many of which have been archived by the Stanford University Piano Roll Project. Their head librarian, Jerry McBride, says these rolls hold a unique — though controversial — significance in sound recording history. “Mahler made rolls, Camille Saint-Saëns,” he says. “There are a handful of rolls by Debussy, and these are the only recordings we have of Debussy playing his own solo piano music. That’s all we have of Debussy playing piano, which is amazing.”

One reason McBride finds them exciting is the potential to study piano-playing styles of the past. “A number of pianists who were recording at that time would have learned piano around the mid-1800s,” he says, “so we can look at these rolls to understand how piano was played in the 19th century, which is quite different than how it’s played today.” McBride notes that a surprising tendency of early century pianists was to add notes and expressions that deviated from the score, unlike the strict playing we’ve come to know. “They were much freer with their approach to interpretation than today,” he says.

The part music archivists can’t agree on is how important these rolls are in understanding piano playing of the past. On one hand, the rhythm and notes on them are precise replications, and sound recordings of the time are scratchy and low-quality. On the other hand, piano rolls can’t express tempo and dynamics of the music as precisely. These were often marked onto the roll by a bystander musician. According to the Pianola Institute, “Duo-Art rolls are more akin to portraits than to photographs, but a portrait can often be the more telling of the two.”

Still, a Rachmaninoff piano roll is sure to be more enjoyable and lively than one of his 1919 recordings with Thomas Edison.

But sound recording got better. In the 1930s, the phonograph, radio, and the Great Depression delivered death blows to the player piano, and it became a memory as quickly as it had spread throughout the nation.

The player piano never completely went away, though. In fact, you can still turn your piano into a self-playing one (for north of 2,700 dollars) if you’d like, and this time around, you can control the songs with your iPad. If, somehow, you still have a player piano that plays paper rolls, you can still buy those too, from Artie Shaw to Britney Spears. The company that produces them, QRS, has been in business since 1900, and they’re proud of their historical trade. Their website claims, “the piano roll has lasted longer than any other standard for recording and reproducing music, and an 80-year-old roll will still sound the same today as the day it was punched.”

We have progressed considerably in sound technology in 100 years, though. These days, if you find yourself with antsy houseguests, there’s no cause for alarm if you don’t have a classic Duo-Art Pianola in the parlor. Just blurt out, “Alexa, play ‘Scott Joplin’s New Rag,’” to get the party started.

Featured image: QRS advertisement from February 4, 1922 issue of The Saturday Evening Post

The 25 Greatest TV Themes of All Time Part 2: Spoken-Word

Read Part One of our look at the Greatest TV Themes here.

Read Part Three: The 40 Greatest Animated TV Series Theme Songs here.

How do you determine the greatest TV show themes of all time? It’s a daunting task. Consider that, in 2016, more than 1400 shows ran on prime-time television in the United States; more than 400 were original scripted programs. And that doesn’t include streaming. Most of those shows have some kind of introduction with music, stretching the line even further. Tom Morello of Rage Against the Machine, suggested that bands should be considered for the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame on the basis of “impact, influence, and awesomeness,” so we’ll use a similar criteria of catchiness, memorability, and appropriateness for the shows. We’ll also be breaking this list into three distinct categories: live-action, spoken-word/voice-over, and animated intro themes. A few months ago, we brought you the greatest live-action themes. Today, we bring you part 2: spoken-word/voice-over themes.

Honorable Mention: Forever Knight (1992-1996)

The opening to Forever Knight (Uploaded to YouTube by ArcoFlagellant)

While not quite great enough to make the list, the opening of Forever Knight does show what a good spoken-word intro does. The best of them establish a premise, which is why they’re so pervasively used in science-fiction, fantasy, and horror programming; they clue the audience into what the show is all about so they can hit the ground running. Forever Knight does that, letting you know that Nick was “brought across” (that is, turned into a vampire) centuries ago while giving you some insight into the ongoing plot.

25. Highlander: The Series (1992-1998)

The opening to Highlander (Uploaded to YouTube by Manticore Escapee)

Based on the cult classic film starring Christopher Lambert, the series gave us Adrian Paul as the immortal Duncan MacLeod (the cousin of Lambert’s Connor from the films). The show proved popular enough the it generated both live-action and animated spin-offs, and Duncan eventually joined Connor on the big screen in 2000 before returning in a television film in 2007. The spoken-word intros changed frequently over the years, adding nuances of plot and situation.

24. Xena: Warrior Princess (1995-2001)

The opening to Xena: Warrior Princess (Uploaded to YouTube by ShakiAldi)

The wildly popular Xena (Lucy Lawless) spun out of Hercules: The Legendary Journeys, a surprise 1994-1999 hit. The two series ranked among the most highly rated syndicated shows in the world during their runs. An unapologetic female action hero on the air during a time when there were precious few, Xena appealed to multiple audiences. The show contained plenty of action, frequently delivered with a nod and a wink. The over-the-top narration set the stage perfectly.

23. Knight Rider (1982-1986)

The opening to Knight Rider (Uploaded to YouTube by NBC Classics)

“A shadowy flight into the dangerous world of a man . . .who does not exist.”

Sounds pretty cool, right? David Hasselhoff played Michael Knight (originally Michael Long, a policeman who was shot and presumed dead, but had his face fixed and a new identity given to him by the Knight Foundation). Knight’s partner was KITT, an artificially intelligent talking car voiced by William Daniels (of St. Elsewhere and Boy Meets World). The introductory narration is provided by Richard Baseheart, who played Knight’s patron, Wilton Knight; the character died in the first episode, but his voice remained.

22. Kung Fu (1972-1975)

The intro to Kung Fu (Uploaded to YouTube by videoblast)

The Kung Fu intro pulls the trick of using dialogue from the show, but it does it in a way that explains the training and journey of Kwai Chang Kane (David Carradine; interestingly young Kane in the intro is played by David’s younger brother and fellow actor, Keith). With this set-up, you understand a bit more about Kane before he went to walk the Earth.

21. Hart to Hart (1979-1984, plus eight made-for-TV movies)

The opening of Hart to Hart (Uploaded to YouTube by TheWraith2006)

Created by novelist Sidney Sheldon, Hart to Hart worked off of the same vibe as Dashiell Hammett’s The Thin Man: rich couple solves crimes. Robert Wagner and Stefanie Powers played the Harts, while Lionel Stander played their assistant, Max (who also delivered the voice-over). The show proved popular enough that it returned for a series of TV-movies in 1993; Stander appeared in the first five before his death in late 1994.

20. Quantum Leap (1989-1993)

The various openings of Quantum Leap (Uploaded to YouTube by TVNostalgia)

Quantum Leap didn’t have the voice-over intro right away, but it did acquire one in season three. Not only does it explain the premise (Dr. Sam Beckett is leaping from body to body across time, trying to set things right), but it also strikes a plaintive note of danger (telling us that Beckett just one day hopes to leap home). The final episode contained one of the great “down” endings in TV history, as a final title card tells us, “Dr. Sam Beckett never returned home.”

19. Buck Rogers in the 25th Century (1979-1981)

The season two intro Buck Rogers in the 25th Century (Uploaded to YouTube by Jack Taylor)

Buck Rogers is one of the longest-running science fiction heroes in popular culture, having first appeared in the 1928 novella Armageddon 2419 A.D. by Philip Francis Nowlan. Since then, Rogers has appeared in comics, novels, film serials, TV series, and theatrical movies. NBC’s TV series launched with a theatrical film that featured a theme song, “Suspension” by Kipp Lennon. That melody was used in the instrumental theme for the TV series. The film’s opening narration by William Conrad was edited down for the first season; in the second season, a new voice-over was delivered by Hank Simms.

18. Battlestar Galactica (1978-1979)

The intro for Battlestar Galactica (Uploaded to YouTube by NBC Classics)

“There are those that believe that life here . . . began out there.” Such are the words of John Colicos, who also played recurring antagonist Baltar. Certainly, BSG is the only show with a voice-over that references the Toltecs and the Mayans. The narration gives you air of mysticism before the soaring theme by the great Stu Phillips crashes in.

17. Law & Order: Special Victims Unit (1999-present)

The intro for Law & Order: Special Victims Unit (Uploaded to YouTube by salehesam101)

With 458 episodes and counting, SVU will break the record for the longest-running American prime-time live-action series this month. Certainly the most successful spin-off ever, it makes the list because of its own iconic opening passage. However, we just couldn’t place it above the original, which you’ll find later on the list. Dun-Dun.

16. The Flash (2014-present)

The various intros to The Flash (Uploaded to YouTube by Phantom)

When Mark Waid took over as writer on The Flash comic book in the 1990s, he took the character’s long-time nickname (The Fastest Man Alive) and ingrained it into the narration that opened each issue: “My name is Wally West, and I’m the fastest man alive.” While the 2014 CW series opted to go with original Flash Barry Allen as its lead, it kept the spirit of Waid’s narrations. Series star Grant Gustin reads the openings in character, which adjust for each season and the arc of that year’s plot. We also use this entry to give a special nod to the Flash’s fellow CW crimefighters, Arrow, Supergirl, and The Legends of Tomorrow, all of whom use a variation of this device.

15. Tales from the Darkside (1983-1988)

The intro and ending to Tales from the Darkside (Uploaded to YouTube by TheSpace163)

Created by Night of the Living Dead director George Romero, Tales from the Darkside was a horror anthology series. Among the many legendary writers who contributed scripts or allowed their work to be adapted were Stephen King, Clive Barker, Harlan Ellison, Robert Bloch, and John Cheever. Romero wrote the opening and closing narrations himself; the lines were performed by Paul Sparer, best known for his work in soap operas like Another World. “Until next time, try to enjoy the daylight.”

14. Farscape (1999-2004)

The four intros to Farscape (Uploaded to YouTube by Farscape)

An Australian-American production that combined the forces of The Jim Henson Company and Hallmark Entertainment, Farscape remains one of the most off-beat science fiction series ever made. Action-packed, frequently hilarious, and put together with a mixture of CGI and Henson creature creations, Farscape tells the tale of John Crichton (Ben Browder), an astronaut who ends up on the other side of the universe and on the run from a fascist army with his collection of alien companions. The intros quickly explain the plot and premise via Browder’s narration, and were updated each season to reflect ongoing changes to the plot. Most notable? Season four’s “Look upward, and share the wonders that I’ve seen,” a grand tease for Crichton’s return to Earth.

13. Babylon 5 (1993-1998)

The five intros for Babylon 5 (Uploaded to YouTube by High Lord Baron)

Sci-fi classic Babylon 5 might be the ultimate expression of the changing introductory voice-over. In each of the first three seasons, a different actor from the show did the narration, with the dialogue changing to reflect the evolution of the story. The most telling change from the first two seasons to the third was the switch from “Babylon 5 was our last, best hope for peace” to “Babylon 5 was our last, best hope for peace. It failed. In the year of The Shadow War, it became something greater: our last, best hope for victory.” Season four included the majority of cast delivering alternating lines of narration, while the final season altered the intro into a collage of dialogue from across the series, ending with a game-changing moment from the previous season finale.

12. The A-Team (1983-1987)

The intro to The A-Team (Uploaded to YouTube by TalkerOne)

A perfect marriage of narration and theme song, the intro to The A-Team captures the story with precision (“In 1972, etc.”) before launching the music with a fusillade of bullets and a literal cannon blast (from the TV-movie pilot). Veteran composers Mike Post and Pete Carpenter composed the main theme, which puts nearly everyone immediately in mind of the flipping jeep.

11. The Incredible Hulk (1977-1982)

The opening of The Incredible Hulk (Uploaded to YouTube by philo1978)

The second live-action Marvel Comics-inspired series of the ’70s (the first being the short-lived Amazing Spider-Man), The Incredible Hulk turned into a hit that ran for five seasons and a handful of TV movies. The theme by Joe Harnell sounds very of its time, but it’s definitely emotive. The narration gives you everything you need to know about Dr. “David” Banner (though other reasons have been posited for the name switch, it was because the producers thought that the alliteration of “Bruce Banner” was too comic-booky; just imagine a comic book character’s name sounding like it came from a comic book), including Bill Bixby’s rather famous line about being angry. The narration was provided by Ted Cassidy (yes, Lurch from The Addams Family). Actual Hulk actor Lou Ferrigno has spent the last decade-plus providing the voice of The Hulk in the various films of the Marvel Cinematic Universe, including the recent Avengers: Endgame (“So many stairs!”).

10. The Six Million Dollar Man (1973-1978)

The intro for The Six Million Dollar Man(Uploaded to YouTube by kelly86410)

“Better . . . stronger . . . faster.” “Gentlemen, we can rebuild him; we have the technology.” You know that the voiceover is a stone-cold classic when it produces multiple quotable lines. Richard Anderson, who plays Oscar Goldman, the boss of the titular bionic man, Steve Austin (Lee Majors) handles the monologue. The Six Million Dollar Man was a huge hit, spawning merchandise, a spin-off (The Bionic Woman), TV movies, and an entire generation of kids that made “chug-chug-chug-chug” noises when they bounced on a trampoline.

9. Charlie’s Angels (1976-1981)

The Season 1 intro for Charlie’s Angels (Uploaded to YouTube by Charlie’s Angels)

Jack Elliot and Allyn Ferguson’s jazzy ’70s main theme became a classic when paired with the smooth, knowing narration of John Forsythe (Charlie himself). The “Once upon a time” opening gently mocks the “very hazardous duties” that female police officers were subjected to, trying to strike an empowering note. However, the show was divisive on that point, with some critics dismissing it as “jiggle TV.” Social critic Camille Paglia recently wrote that the show was an “effervescent action-adventure showing smart, bold women working side by side in fruitful collaboration.” The show proved exceedingly popular for a time, even with cast replacements. After an abortive late ’80s reboot failed to materialize, the show has since seen life as two theatrical films, a revival TV series, spin-off comics, and a pending return to the big screen.

8. The Outer Limits (1963-1965; 1995-2002 revival)

The 1963 intro to The Outer Limits (Uploaded to YouTube by Florin MC)

The Outer Limits wastes no time getting to the creepy. As the picture begins to fail, a voice tells us, “There is nothing wrong with your television set; do not attempt to adjust the picture.” Most often compared to its fellow anthology, The Twilight Zone, this series hewed more closely to science-fiction, whereas Zone cast a wider net. While the original series only ran for two seasons, the words of the intro have stuck around in popular culture ever since, meriting a Top Ten spot on the list.

7. Dragnet (1949-1957 on radio; 1951-1959; 1967-1970 revival)

The 1954 intro to Dragnet (Uploaded to YouTube by Mill Creek Entertainment)

Jack Webb played Detective Joe Friday across three mediums off-and-on for 21 years. He was the lead in the radio drama, the first TV series (and its spin-off film), and the series revival. From the radio through the second TV show, two ongoing narration pieces were used. The first was an announcer, letting you know that the story you are about to see is true (although the names have been changed to protect the innocent). The second element is Friday himself, setting the L.A. scene and introducing himself. The no-nonsense set-up is the ancestor of our next entry.

6. Law & Order (1990-2010; on cable somewhere at this precise moment)

The spoken-word introduction to Law & Order (Uploaded to YouTube by Florin MC)

A franchise engine of the highest order (every pun intended), Dick Wolf’s Law & Order ran for 20 years while producing six direct spin-offs (with L&O in the name), indirect spin-offs like Conviction (the 2006 series), absorbing characters from other shows (Richard Belzer’s Detective Munch from Homicide: Life on the Streets), and sharing a fictional universe and ongoing character crossovers with programs like New York Undercover and the family of Chicago shows (Fire, P.D., Med, etc.). The iconic introduction, echoed on most of the shows that bear the Law & Order name (including SVU from earlier in the list), lets you know that the show will follow both the police (Law) and the prosecutors (Order). Dun Dun forever.

5. The Odd Couple (1970-1975)

The intro to The Odd Couple (Uploaded to YouTube by retrorebirth)

Certainly one of the greatest television comedy series, The Odd Couple was based on the film that was based on Neil Simon’s stage play. Starring Tony Randall and Jack Klugman, the series had the distinction of doing so well in summer reruns that its second-run performance became the deciding factor each time it was awarded a new season. At the close of its run, the show was given a genuine finale episode, wherein Randall’s Felix re-marries Gloria and moves out. Multiple remakes of The Odd Couple exist on stage and screen, including a gender-flipped play, a remake with an African-American cast, and, this is true, an animated take with dog and cat roommates (The Oddball Couple, which ran on ABC in 1975).

4. The Lone Ranger (1949-1957)

The intro to The Lone Ranger (Uploaded to YouTube by TeeVees Greatest)

Cue The William Tell Overture.

Narrator: The Lone Ranger!

Lone Ranger: Hi Yo Silver!

Narrator: A fiery horse with the speed of light, a cloud of dust and a hearty, ‘Hi Yo Silver!’ The Lone Ranger!

Lone Ranger: Hi Yo Silver, away!

Narrator: With his faithful Indian companion Tonto, the daring and resourceful masked rider of the plains led the fight for law and order in the early west. Return with us now to those thrilling days of yesteryear. The Lone Ranger rides again!

And scene. Do you really need anything else?

3. The Adventures of Superman (1940-1951 radio; 1952-1958 TV)

The intro for The Adventures of Superman (Uploaded to YouTube by MissingPieces4U)

Though the opening narration may have been imported in large part from the radio, they remain some of the most famous words in the history of popular culture. It’s all there . . . “Look! Up in the sky! It’s a bird! It’s a plane! It’s . . . Superman!” You get that he’s a “strange visitor from another planet.” You learn that he’s “faster than a speeding bullet . . . more powerful than a locomotive . . .” Basically every word of this is classic Americana. It’s like the super-hero Pledge of Allegiance. There is zero chance that you haven’t heard some part of this in the course of your everyday life.

2. Star Trek (The Original Series, 1966-1969)

The intro to Star Trek: The Original Series (Uploaded to YouTube by dinadangdong)

A perfect marriage of text, image, and music, the opening narration of Star Trek gives you everything you need to understand the show and a dose of otherworldly tunes to go with it. Alexander Courage composed the theme, and the immortal words are delivered by Captain James T. Kirk himself, William Shatner. It’s been repeated in films, covered by Patrick Stewart for the first live-action spin-off (Star Trek: The Next Generation), and completely assimilated by popular culture. Or did it assimilate us? Only the Borg know for sure.

AND . . . the Greatest TV Spoken-Word Intro belongs to . . .

1. The Twilight Zone (1959-1964; revivals from 1985-1989, 2002-2003, and 2019-present)

The intros to The Twilight Zone from 1959 to 2003 (Uploaded to YouTube by Tardis & Beyond)

Witness if you will, a TV series with a basic premise so powerful it’s spawned a legion of imitators and has been rebooted itself three additional times. Submitted for your approval, a show so gripping that people who saw individual episodes as children still remember the endings decades later. Amazingly, though the lines of the intro were tweaked across seasons, every iteration remains incredibly memorable. Part of that was the delivery of the show’s creator and host, Rod Serling, and part of it was Serling’s own talent for finding that cold space in your mind and squeezing. Not every episode was scary, and not every episode had a twist, but the intro let you know that you had to be ready for anything. It’s timeless, it’s iconic, and it’s our Number One.

Read Part One of our look at the Greatest TV Themes here.

Featured image: Pictorial Press Ltd / Almy Stock Photo.

Cartoons: Amusing Musicians

Want even more laughs? Subscribe to the magazine for cartoons, art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

Drucker

July 28, 1951

Bob Barnes

March 24, 1951

Ben Roth

March 10, 1951

Corka

March 10, 1951

Tom Henderson

March 3, 1951

RJ Wilson

February 27, 1951

Dave Seward

September 16, 1951

Want even more laughs? Subscribe to the magazine for cartoons, art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

30 Years Ago: Soundgarden Lit the Fuse for the Seattle Explosion

It’s been called “The Seattle Sound.” It’s also been called, much to the disdain of the musicians that hail from the Jet City, “grunge.” Inspired in varying fractions by the punk stylings of bands like Black Flag, the doomy riffing of metal acts like Black Sabbath, and the indie sensibilities of groups like The Pixies, the sounds that brewed in the Pacific Northwest in the 1970s and 1980s become one of the defining tones of the 1990s. A kind of conventional wisdom has gelled around the notion that Nirvana was the band the broke the doors open in 1991; however, the first band from that scene to make the move to a major label is also one that found enormous success, only to later lose their voice. That band was Soundgarden.

In all fairness, Seattle produced plenty of well-known musical acts in the decades prior to the flying of the flannel flag. The vocal stylings of The Fleetwoods and the surf rock of The Ventures emerged from the Seattle-Tacoma area in the 1950s. Jimi Hendrix made his mark after traveling to England to break through. Progressive metal band Queensryche formed in 1980 before becoming hitmakers a decade later. But the undisputed rock royalty that would have direct ties to the later “grunge” scene were Ann and Nancy Wilson, the sisters at the center of the massively successful (and still touring) Heart. Founded in Washington state before finding success in Canada and dropping their debut in 1975, Heart inspired a number of younger musicians with their musical prowess and work ethic, eventually becoming “big sister” and mentor figures to a number of stars-in-the-making.

The Seattle scene that became mythologized by MTV started forming in the ’80s. Brothers Andrew and Kevin Wood put together Malfunkshun, a rock band noted for their humor and Andrew’s glam vocals and magnetic stage presence. The Melvins, led by singer-guitarist Buzz Osborne and second drummer Dale Crover, formed in Montesano in 1983; the band applied the heaviness of Black Flag to the varied tempos of their music. A year later, Green River debuted, boasting a line-up that included future members of Mudhoney and Pearl Jam.

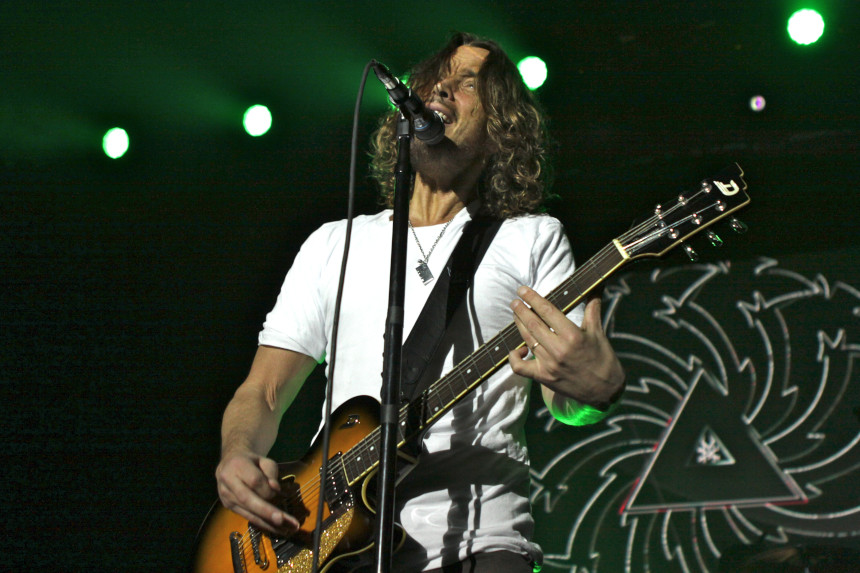

It was in this environment of furious musical activity that Soundgarden formed. The 1984 line-up featuring Kim Thayil on guitar, Hiro Yamamoto on bass, and Chris Cornell on . . . drums? It may seem hard to believe now, but one of the most charismatic vocalists of all time started off behind the kit; he was the singer then too, of course, but he wouldn’t emerge from behind the drums full-time for another year. The nascent band, along with Green River, was among the early signees to local label Sub Pop.

Soundgarden began to grow their fanbase from Screaming Life and the follow-up EP, Fopp. Though primed for a swing at the major labels, Soundgarden opted to sign with California indie SST Records, the home of Black Flag. The resulting album, 1988’s Ultramega OK, earned positive attention, garnered MTV airplay for the video “Flower,” and enabled the band to tour the U.S. and Europe. The album would eventually be nominated for a Grammy in the Best Metal Performance category.

Flower by Soundgarden (Uploaded to YouTube by Sup Pop

After the success of OK, the band made the difficult decision to sign with a major label. When A&M took them on, some of the original fans took umbrage to their hometown heroes leaving the indies behind. Nevertheless, the band found itself on a steadily upward trajectory. When their major label debut, Louder Than Love, dropped in September of 1989, they found themselves with an album in Billboard’s Top 200. Tours with Voidod and Guns ‘N’ Roses followed.

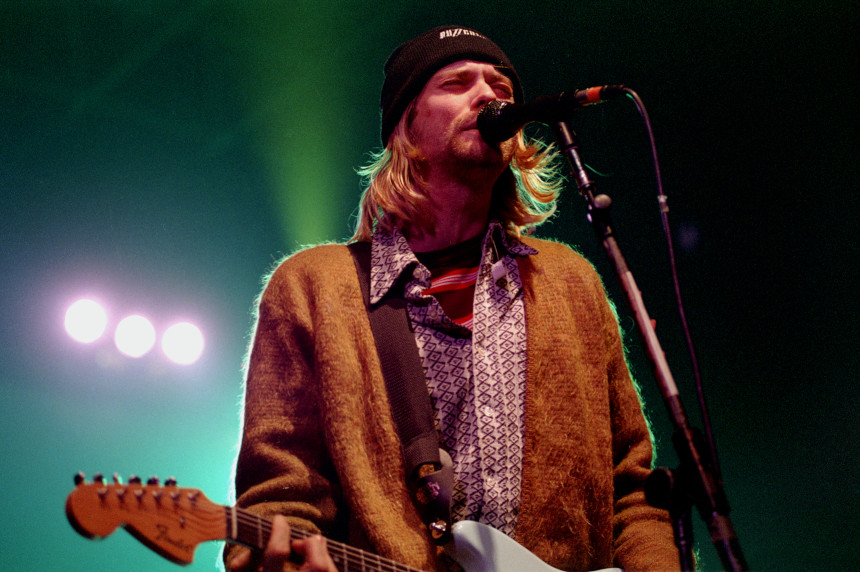

Soundgarden’s emergence threw a spotlight on the scene that Sub Pop had helped cultivate. Bands like Nirvana and Mudhoney had gained studio experience while honing their craft.

1990 and 1991 brought enormous upheaval to music. After several years of hair-metal dominance, alternative stalwarts like R.E.M. and Jane’s Addiciton and significant hip-hop artists like Ice Cube began to get more attention. In March of 1991, the introduction of the Nielsen SoundScan tracking system dramatically altered the make-up of the charts; previously, Billboard chart placement turned on phone calls and reports from stores, which frequently included mistakes and outright fabrications. The new system tracked the cold hard data of sales alone, and that shook up the traditional perception of what genres were popular. At the same time, MTV’s proliferating number of shows that focused deeply on genres, like Headbanger’s Ball (metal), Yo MTV Raps! (hip-hop), and 120 Minutes (alternative), allowed a greater number of acts to be seen.

In the midst of this, a serendipitous wrinkle arrived on the scene via Hollywood. Cameron Crowe had written for Rolling Stone as a teenager and had transitioned to the successful screenwriter of Fast Times at Ridgemont High and the writer/director of Say Anything. Along the way, he married Nancy Wilson of Heart. Crowe set his new film, Singles, against the backdrop of the city’s vibrant music scene, inspired in part by the community he witnessed in the wake of Malfunkshun singer Andrew Wood’s death via overdose in March of 1990. Filming commenced in March of 1991. The movie featured a number of musicians from the city in visible roles, notably Ament, Gossard, and Eddie Vedder as the other members of Matt Dillon’s band, Citizen Dick. Cornell wrote some tunes to go along with some fictional song titles, and Soundgarden and Alice in Chains both appear performing in the film. The studio, however, wasn’t quite sure how to market it, so it wound up sitting on the sidelines for months. While the film waited, the music didn’t.

In the fall of 1991, Nirvana released the video for “Smells Like Teen Spirit,” and there was an explosion of interest in Seattle. As it happened, Soundgarden, Alice in Chains, and Pearl Jam all either had albums out or ready to go. Nirvana’s Nevermind raised all boats. Facelift, the debut disc by Alice in Chains, had been released in 1990 and grown steadily, but it surged again with the Seattle association. Nevermind, Soundgarden’s Badmotorfinger, and Pearl Jam’s Ten all arrived within one four-week period. The Alice in Chains and Soundgarden releases would sell more than two million copies each, while Ten and Nevermind went on to sell a stunning 13 and 30 million worldwide, respectively.

The Seattle bands hadn’t opened a door for alternative rock; they’d torn down a wall. Coupled with the new touring vehicles like the Lollapalooza tour and steady airplay on MTV, alternative rock exploded. Veterans like the Red Hot Chili Peppers would take Nirvana, Pearl Jam, and Chicago’s Smashing Pumpkins out as opening acts while a signing frenzy began as major labels began to look for the “next Seattle” or the “next Nirvana.” In the summer of 1992, the soundtrack to Singles was released three months before the film; though the music had been selected and included long before the breakthrough occurred, the disc’s inclusion of Soundgarden, Alice in Chains, Pearl Jam, Screaming Trees, Smashing Pumpkins, and more powered it to double-platinum status.

For the next few years, the bands enjoyed huge success. Soundgarden’s Superunknown sold more than twice as many albums as Badmotorfinger, as did Alice in Chains’ Facelift follow-up, Dirt. The two bands and Pearl Jam would appear on the Lollapalooza main stage. Nirvana found themselves anointed as a kind of post-punk Beatles; the media and many fans viewed them as the figureheads of the scene. Unfortunately, Nirvana’s singer/guitarist Kurt Cobain succumbed to his combination of depression and addiction, and took his own life in April of 1994. Cobain’s death took the winds out of the sails of the alternative explosion. Later wave bands like Bush and Weezer had big successes, but the genre had lost its most visible frontperson.

Today, it’s hard to look back at the scene without melancholy. Original Alice in Chains vocalist Layne Staley died from an overdose in 2002, and Cornell would take his own life in 2017. The raw power and creativity of the music was driven in part by the real issues afflicting the musicians themselves; that honesty was an integral component of why they connected with audiences. While some may regard the Seattle explosion as a phase or a snapshot in time, the pervasive nature of music and video streaming services allows new generations of fans to discover these bands and their songs on a continually recurring basis. Even as the musicians leave us, their songs, more powerful than a fad or passing interest, will continue to endure.

Featured image: Brian Patterson Photos / Shutterstock.com.

The Stooges Set the Stage for Punk 50 Years Ago

No matter how you cut it, 1969 will always be one of the most significant years in music: Woodstock. Altamont. The Beatles play in public for the last time. The Who record Tommy. Johnny Cash plays San Quentin. Diana Ross and The Supremes split. It was year of wall-to-wall classic albums, from Led Zeppelin, Yellow Submarine, and Neil Young appearing in January to Let It Bleed by The Stones and the Jackson 5’s debut in December.

Tucked in among those timeless records was another release that would have a seismic impact, its influence growing as time went on. Joining The Sonics, Velvet Underground, and MC5 as a forerunner of punk, The Stooges unleashed their self-titled debut 50 years ago – yes, 50 years ago — this week, completing a foundation for punk rock that would be built upon by the New York Dolls, Patti Smith, The Ramones, Blondie, and Television.

The Stooges formed in 1967 in Ann Arbor, Michigan, near their Detroit contemporaries MC5, and they indulged in a loud and rude brand of garage rock that’s since been dubbed proto-punk. The core of the band was brothers Ron and Scott Asheton on guitar and drums, respectively, Dave Alexander on bass, and Jim Osterberg on vocals. Osterberg would be credited as Iggy Stooge on the record, but the world would soon come to know him as Iggy Pop.

The Stooges (Uploaded to YouTube by RHINO)

The Stooges soon built a reputation for intense live performances. The extremely limber and often shirtless Pop twisted his body to the music, frequently smearing himself with peanut butter and other foods, leaping off the stage, crashing into equipment, and even cutting himself. The sound of the band ran from bluesy grooves to pummeling rock, sometimes within the same song. Tunes like “I Wanna Be Your Dog” leaned heavily on three distorted guitar chords while incorporating sounds like sleigh bells and a one-note piano. When Danny Fields from Elektra Records went to scout the MC5, he saw The Stooges, too; he signed both bands.

While the intensity of the band powered their sound, it was the totally bonkers stage presence of Pop that helped cement them as iconic. Even before the first album dropped, tales of their shows were legend. Henry Rollins, former lead singer of hardcore punk legends Black Flag and The Rollins Band, grew up idolizing Pop. In a hilarious pair of videos, he recounts playing with Pop on multiple occasions throughout the ‘90s; he regards “Jim Osterberg” and “Iggy Pop” as almost two separate beings, saying, “Jim is cool; Iggy is like this terrifying monster of rock and roll.” Rollins also recalled on a VH1 special that Pop was “to my knowledge, the first guy to go off the stage into the crowd.” Alice Cooper, upon seeing Pop for the first time recalled, “I went, who is this guy? I thought I was the freakiest guy out there.”

Brian Eno said (possibly apocryphally), that not that many people bought 1967’s The Velvet Underground & Nico, but everyone that did started a band. In the case of The Stooges, they got John Cale from The Velvets to actually produce their first record. That Stooges sound was uniquely primitive and primal, and Cale managed to get that feel on the record.

As was the case with that first Velvet Underground album, The Stooges didn’t set the world on fire. Sales were modest and reviews weren’t glowing, but were frequently tinged with grudging respect. Writing for Rolling Stone at the time, Edmund O. Ward gave this classic summation: “Their music is loud, boring, tasteless, unimaginative and childish. I kind of like it.” The follow-up album, 1970’s Fun House, worked much the same way. The band earned a significant fan in David Bowie; Bowie, along with Pop, would produce the third album, 1973’s Raw Power, which featured the addition of guitarist James Williamson to the line-up.

Though the records sold poorly, they found an audience among nascent musicians, many of whom would coalesce around the New York City punk scene in the years that followed. Bands like The Ramones, Blondie, and Television were influenced by The Stooges, and Pop befriended many in that New York scene. The Stooges became a forerunner of the New York Dolls and those aforementioned acts that emerged, alongside Talking Heads and others, as the cornerstone of American punk rock. In the documentary Punk Attitude, Thurston Moore of the band Sonic Youth said that Pop never even realized that The Stooges had sold any records until he moved to New York and met bands like The Ramones that he had influenced, “which was shocking for him.”

The Stooges are inducted into The Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. (Uploaded to YouTube by Rock & Roll Hall of Fame)

Over the years, The Stooges served as an influence to musicians across a multitude of genres, notably punk and metal. Kurt Cobain of Nirvana called Raw Power his favorite album. Reunions occurred here and there with musicians moving in and out of the band, and live albums being released, but the band didn’t go back into the studio together again until 2007’s The Weirdness. By that point, The Stooges had been playing and touring together consistently again since 2003. In 2010, the band was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. The Stooges disbanded for good in 2016 following the deaths of the Asheton brothers and Mackay; Williamson and Pop felt that should be the end. That same year, Jim Jarmusch’s documentary about the group, Gimme Danger, was released.

The Stooges were never the biggest band, but they proved that you didn’t have to be. They played hard, lived rough, and became major influences on multiple generations of players. They got to see their music drive other bands, and then they came back to play alongside them for years. When Billie Joe Armstrong of Green Day inducted the band into the Rock Hall, he read a list of roughly 100 bands that counted The Stooges as an influence while admitting that there were legions more. Iggy sang “Raw power got a magic touch,” and he was absolutely right.

Featured image: Shutterstock.com

The Week of Peak Disco

Can you pinpoint the exact moment that a musical movement peaks? It’s easy to define music to nonspecific eras: you have the British Invasion, the early 1990s Alternative Explosion, and so on. However, the unassailable peak of disco happened the week of July 21, 1979, when the top six songs in the U.S. (and seven in the Top Ten) were classified as disco tunes. Over the following few weeks, every trace of the style would vanish from the charts. This is the story of a genre’s rise, greatest moment of triumph, and fall.

An exact date for the creation of disco is impossible to pin down, but we can trace its development from earlier decades to the 1970s. One significant step in the genre’s development was the ongoing slate of private parties hosted by New York DJ David Mancuso at his home starting in 1970. Mancuso’s approach was copied by others; as his own “The Loft” became the epicenter of a new dance culture, it spread into other private parties and clubs. The Loft was notable for the blended audiences that it attracted; no barriers were placed on ethnicity or sexuality, and the music had to be danceable and generally celebratory.

The sound of disco came from a variety of places. Motown R&B played a part, as did the soul stylings of groups from cities like Philadelphia, like The O’Jays and The Stylistics. Producers like Tom Moulton pushed the record format when it came to dance, extending single lengths by using 12” vinyl and innovating the remix approach that added or enhanced elements of songs. The psychedelic soul sound associated with later Temptations records and the funk of George Clinton’s Parliament-Funkadelic added other ingredients to the brew.

The O’Jays perform “Love Train” (Uploaded to YouTube by the O’Jays)

From a cultural standpoint, the shift from the 1960s to the 1970s opened the door for new things. As the counterculture movement died off and Vietnam continued, economic uncertainty plagued the country. The ongoing social turmoil became a crucible for new and reinvented forms of music, including the evolution of heavy metal, punk, hip-hop, and disco. In the book Beautiful Things in Popular Culture, Simon Frith said, “The driving force of the New York underground dance scene in which disco was forged was not simply that city’s complex ethnic and sexual culture, but also a 1960s notion of community, pleasure and generosity that can only be described as hippie. The best disco music contained within it a remarkably powerful sense of collective euphoria.” Soon dance records that broke in the clubs found success on the radio and in record stores, adding some early fuel to the movement.

“Rock the Boat” by The Hues Corporation (Uploaded to YouTube by The Hues Corporation / RCA Victor)

On the charts, a number of songs that could arguably be classified as disco emerged as hits in the very early 1970s. Among these were “Love Train” by The O’Jays (1972) and “Love’s Theme” by Barry White’s The Love Unlimited Orchestra (1974). When “Rock the Boat” by The Hues Corporation hit #1 in May of 1974, many declared it to be the first disco #1, though others held up “Love’s Theme” (which topped the charts in February) as the first. Regardless of which was “first,” it was evident that the style had a place on the charts and was primed to grow. Carl Douglas’s “Kung-Fu Fighting” and George McRae’s “Rock Your Baby” also hit #1, with “Rock” having the added distinction of being the first disco #1 in the U.K. The success of disco rolled into 1975, with landmark tracks like Van McCoy’s “The Hustle” and the commercial breakthroughs of Donna Summer and KC and The Sunshine Band.

“Night Fever” by The Bee Gees (Uploaded to YouTube by beegees)

The popular acceptance of the form took it into more mainstream clubs and into film and television. A 1976 New York magazine article inspired the disco-driven 1977 film Saturday Night Fever. The already popular Bee Gees had turned their attention to more dance-oriented sounds by 1975, and the trio had created hits like “Jive Talkin’” and “You Should Be Dancing” (1976). The Bee Gees agreed to craft songs for the film; those tunes, as well as songs they wrote for others and contributions from different acts, would form one of the best-selling soundtracks in history. The success of the Oscar-nominated movie and the soundtrack (over 16 million albums sold) remarkably elevated the profile of the genre to even greater heights.

Between 1977 and 1980, roughly 22 songs that fit into the disco genre hit number one on the Billboard Hot 100. These included obvious numbers like “I Will Survive” by Gloria Gaynor and “Dancing Queen” by Abba, as well as critically acclaimed pieces “Don’t Leave Me This Way” by Thelma Houston (a cover of a Harold Melvin & The Blue Notes song, Houston’s version won a Grammy for Best Female R&B Vocal Performance in 1977).

“Don’t Leave Me This Way” by Thelma Houston (Uploaded to YouTube by Thelma Houston)

Despite the popularity of the form, there were definitely dissenters. One of them was Steve Dahl, a rock DJ who lost his job at Chicago’s WDAI when the station switched from a rock format to disco. Dahl was hired by WLUP and worked hard to stir anti-disco backlash. After promoting a few events, Dahl participated in a promotion at Comiskey Park, home of the White Sox. Disco Demolition Night on July 12, 1979, encouraged fans to bring disco records to the double-header between the Sox and Tigers where the discs would be blown-up in center field. The event got out of hand early when fans that couldn’t get into the sold-out affair broke into the stadium anyway. Beer, firecrackers, and albums rained on the field throughout the first game. After the crate of records was detonated between contests, thousands of fans rushed the field. Police were called, and eventually the White Sox had to forfeit the game (it’s the last American League behavior-forfeit on record). While many, like Dahl, dismissed the circumstances of the event as harmless fun gone out of hand, others like Rolling Stone writer Dave Marsh expressed that a lot of the hostility toward disco included bigotry toward black, Latino, and gay artists and fans.

“Hot Stuff” by Donna Summer (Uploaded to YouTube by Donna Summer Universal Music Group

Despite the anti-disco sentiment, a few days after the Comiskey Park incident, the Billboard Charts reflected the week of peak disco. Seven of the Top Ten were disco tracks, including: “Bad Girls” by Donna Summer (#1); “Ring My Bell” by Anita Ward (#2); “Hot Stuff” by Summer (#3); “Good Times” by Chic (#4); “Makin’ It” by David Naughton (#5); “Boogie Wonderland” by Earth, Wind, & Fire with The Emotions (#6); and “Shine A Little Love” by Electric Light Orchestra (#8). ELO, like Blondie, weren’t a traditional disco band, but did release songs that employed the sound. Despite this high, disco was about to hit its inglorious low.

“My Sharona” by The Knack (Uploaded to YouTube by The Knack / Universal Music Group)

On August 25, “My Sharona” by The Knack began a six-week run at #1. Critics typically lump The Knack in with “new wave” rock acts that also included multi-genre stylists Blondie, Elvis Costello, and others. Disco would continue to dot the charts for a while, but the cultural backlash caused many artists to simply relabel themselves as “dance.”

When MTV kicked off in 1981, it effectively killed disco for good in two ways. The first is the unfortunate reality that that the network played very little in the way of black artists in its early days. The second is that the channel embraced bands that were already making videos or working overseas (where the “video clip” format was already popular), resulting in a massive push for predominantly white, new-wave-related bands and English bands. Everyone seems to know that the first video played on MTV was “Video Killed the Radio Star” by The Buggles, but the next nine were from Pat Benatar, Rod Stewart, The Who, Ph.D., Cliff Richard, The Pretenders, Todd Rundgren, REO Speedwagon, and Styx. Black artists wouldn’t break through on the channel until the massive success of Michael Jackson and Prince in the following two years forced the network to catch up.

Gloria Gaynor’s “I Will Survive” enjoys ongoing life in other media and sporting arenas. (Uploaded to YouTube by Gloria Gaynor / The Orchard Enterprises)

Today, disco culture is a staple of films and TV, as seen in everything from Boogie Nights to Pose to The Martian (Matt Damon’s character may have hated it, but Jessica Chastain’s loved it). The musical style has adapted and integrated into a variety of genres, including EDM and hip-hop, where sampled hooks are still regularly mined from disco classics. Package tours of disco artists continue to circulate. The influence is felt in a number of popular songs of the past few years, among which are Daft Punk’s “Get Lucky” (which features Nile Rodgers of Chic), “Uptown Funk” by Bruno Mars, and “Can’t Feel My Face” by the Weeknd. Disco may never have a proper, world-dominating comeback, but it never truly went away. It’s fair to say that no matter how you try to kill it, it will survive.

3 Questions for David Crosby

David Crosby’s rise to fame was plagued by drug and alcohol use and a fiery temperament that burned a lot of bridges. A new documentary, David Crosby: Remember My Name, opening in theaters in July, takes us through his incredible triumphs and low, low points, from The Byrds to Crosby, Stills, and Nash and beyond. Now, after overcoming the addictions that nearly killed him, a liver transplant, and multiple heart surgeries, the 77-year-old is on the road again and happy. “It’s really strange to have the best part of your life near the end,” he says. “I’m glad [producer] Cameron Crowe gave me no place to hide in the film. We wanted to do an honest portrayal of a human being not a shine job.”

He believes music can change minds. At every show, he performs “What Are Their Names,” which includes the following lyrics:

I wonder who they are

The men who really run this land

And I wonder why they run it

With such a thoughtless hand

What are their names

And on what streets do they live

I’d like to ride right over

This afternoon and give

Them a piece of my mind

About peace for mankind

Peace is not an awful lot to ask

Jeanne Wolf: People call you a survivor. I like to think of you as an unstoppable artist-adventurer.

David Crosby: I’m not exactly unstoppable, but the truth is, I think I must be the luckiest guy I know. I was supposed to be dead 20 years ago, and here I am just having a blast. I’ve done four records in four years and I’m halfway through a fifth one. I didn’t do it to prove anything. I just did it because I had the songs and it was fun. I think it has to do with your attitude about life. If your whole concern is your physical exterior, getting old is kind of hard. If you’re concerned with your heart, your mind, and your soul, it is pretty much fun.

When I’m on stage, I’m the happiest guy in the world. I never sing anything exactly the same. I’m always winging it. It’s like having your own rocket ship. You can feel this total freedom and the joy of the connection that you have with the other musicians. This magic that you’re making together is freakin’ wonderful.

Then you eat a piece of pizza and try to sleep on a bus.

Looking back, we went through some tough times inside Crosby, Stills, and Nash. We were all competing with each other. The result was some really good music, but there was never the kind of joy making it that collaborative effort has. If you’re working with somebody for the same aim, it’s a joy, but not if you’re going, “I’m better than you are.”

Now my son, James Raymond, produces my records and plays with me in all my gigs. He’s the keyboard player and my best writing partner. So it’s really pretty wonderful. His mom put him up for adoption when he was born. I knew he existed but I didn’t know how to find him. Then when he was 30 he found me. He got ahold of me and he was so nice. You know those meet-ups usually go badly, but he gave me a clean slate, gave me a chance to earn my way into his life.

JW: People are still curious about your years of self-destruction and addiction. Do you get weary of talking about it?

DC: I learned to be able to tell my story because it can help other people who are trying to deal with addiction. You start in the meetings. Then, people come to you and say, “My brother or my son or my wife or my lover is in such deep trouble — what can I do?” I can usually help, but the truth is, you can only do it yourself, even if people are sympathetic and supportive. Sometimes they lock you up and that’s the only way you get straight. You have no choice if you’re in prison. That’s what finally happened to me. But when you get out, good luck if you haven’t figured things out for yourself.

I do think that the hard things that you go through shape you and, in many cases, make you better. I don’t know anybody I like that isn’t covered with scars. I think that after you’ve gone through something really tough, then when you see somebody else going through something tough, you have compassion.

JW: Your songs have been anthems for change. Can lyrics really make a difference?

DC: Music is a really wonderful thing for transmitting ideas, and ideas are the most powerful stuff on the planet. People like me come from the troubadours in the Middle Ages in Europe carrying the news from town to town. Right? And the town criers. “It’s twelve o’clock and all is well!” or “It’s twelve o’clock and you elected that guy to be president!” Most of our job is to take you on emotional journeys and make you boogie. But if your government starts shooting down your children when they’re at college protesting legally and unarmed, as they did at Kent State, you have to sing about it. And we did. That’s the witness part. Short of that, I think you have to be really careful about how you do it because I don’t like the people who just adopt the cause of the week.

Most of my songs come to me at night at home. We always have dinner together as a family, and then I go to build a fire and I smoke some pot. I take a guitar off the wall and I play and I see where it goes. Very often, I will find a new piece of music. The other way that happens is, I get a flash of some words that I like. That’s the thing I learned from Joni Mitchell, who told me, “Write everything down, otherwise it didn’t happen.”