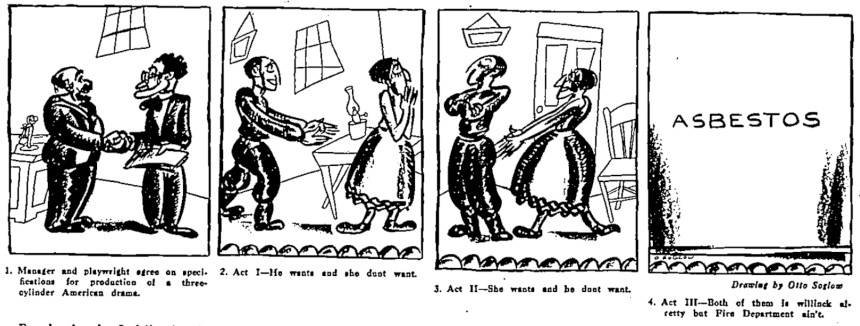

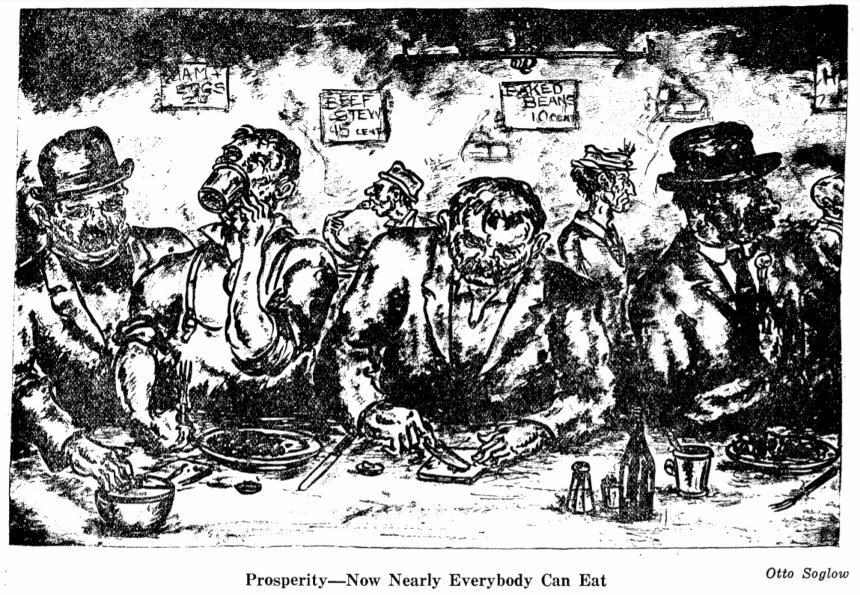

The Premier Pantomime Cartoonist

If you looked at a newspaper or magazine cartoon in, say, the 19th century, it might seem a little … off. The illustrations were packed with pen strokes, and captions were often comprised of two to four lines of wordy dialogue, resulting in the effect of a short conversation between two sketched characters.

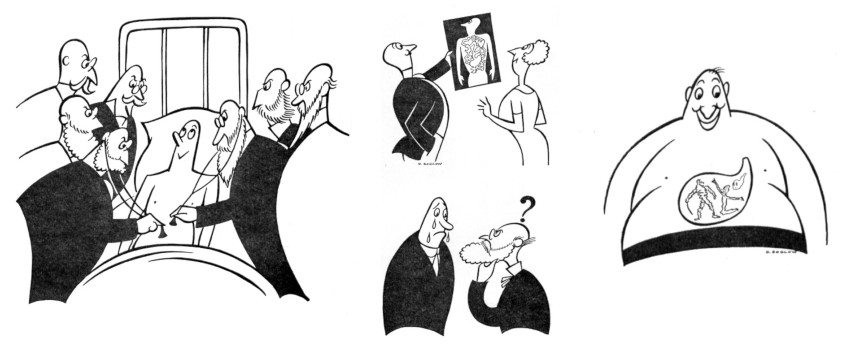

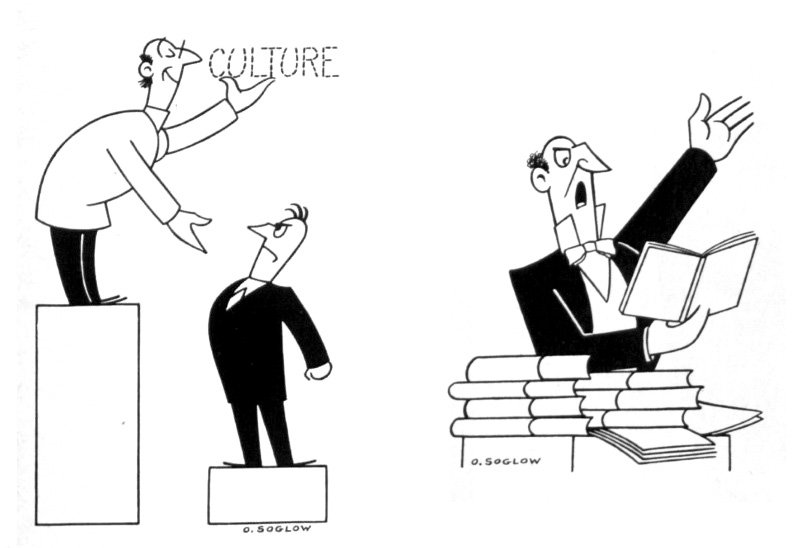

One of the cartoonists responsible for upending this style — and pioneering the kinds of strips we know today — was Otto Soglow, born on this day in 1900. At The New Yorker and, later, in this magazine and newspapers across the country, Soglow pared down lines in his illustrations, presenting a clean, minimalist rendering of whimsical characters. In the way of captions, uniquely, he often used very few or none at all, making a name for himself as a pantomime cartoonist with his popular strip The Little King, which ran for almost 40 years.

Soglow didn’t set out to become a cartoonist. A passionate performer, he dropped out of high school to pursue a career in acting. He worked as a shipping clerk, a packer, and even as a baby rattle painter before taking up illustrating professionally. In the 1920s, Soglow drew toons for the pages of radical New York publications like The New Masses and The Liberator. Influenced by the politics and aesthetics of the Art Students’ League, his work during this time depicted gritty cityscapes, working-class scenes, and socially-conscious themes.

In the August 1922 issue of The Liberator, which had published one of Soglow’s earliest illustrations the month before, the editors apologized for neglecting to credit him, saying “Soglow is to give the Liberator more of his strong work, so full of atmosphere, poetry, and sensitive observation.”

By the late ’20s, he was publishing toons and small illustrations in The New Yorker, alongside names like Peter Arno, Helen Hokinson, and James Thurber. In the magazine’s obituary for Soglow, the author noted that while his style was once busy with ink, it became purer over the years, eventually omitting all details except the most necessary: “There was nothing to distract the eye or the mind.” The New Yorker was also where Soglow introduced his most famous and enduring character: the little king.

In various weekly adventures for more than 40 years, Soglow’s “cartoon monarch” stumbled through silent, playful scenarios at the perplexity of his royal court. Far from a stereotypical depiction of a severe ruler, Soglow’s childlike king displayed no interest in power, but rather enjoyed simple pleasures like ice cream and zoo animals. While his barrel-chested guards smoked cigars, the short stubby sovereign blew bubbles out of a toy pipe. Soglow’s sight gags in his Little King strips — which were syndicated in papers around the country from 1934 to 1975 — were endearing nods to our better, more innocent, angels.

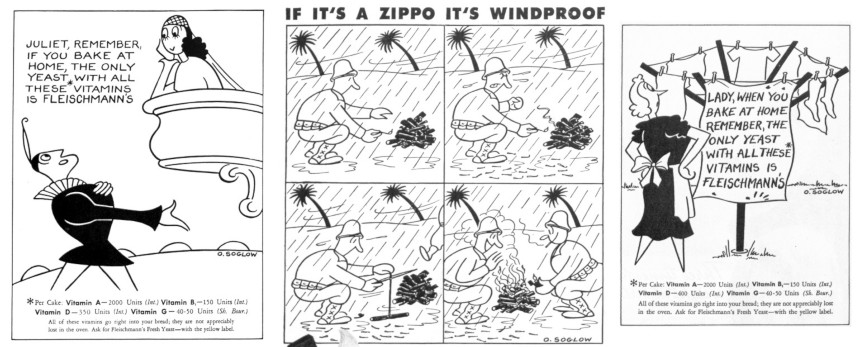

In taking his cartoons to a larger audience, the once-socialist Soglow struck a deal with newspaper magnate William Randolph Hearst. If this move wasn’t quite contradictory, his career quickly took a commercial turn as he began illustrating ads for Realsilk socks, Mutual Life Insurance Company, Fleischmann’s Yeast, Pepsi-Cola, oil companies, and others. His ads — of course, lacking the quaint charm of his other work — appeared in The Saturday Evening Post for decades. Soglow was also a staunch supporter of the war effort, designing propaganda posters and supporting art programs for soldiers.

Although he likely made a great deal of money illustrating and cartooning, Soglow never lost his desire to perform. New York newspapers in the ’30s and ’40s described him as a hit at parties, giving impersonations and magic tricks that rivalled Chaplin’s. Given his earlier penchant for the poetic and the critical, discerning audiences might be tempted to read some semblance of subtle geopolitical commentary into The Little King, but Soglow said that was baseless and “just plain silly.” As for the origin of the beloved character that graced funny pages for decades, he gave no deep, revelatory explanation; “He just happened.”

Soglow drew The Little King until he died in 1975. Although he isn’t remembered widely by the populace, the cartoonist is decidedly among the ranks of important New Yorker illustrators, and the magazine still uses his artwork in print and online. In a review of a new Little King coffee table book in 2012, Jeet Heer called Soglow “one of the central cartoonists of mid-century America.” Flipping through the comics of any paper in the country before and after Soglow, it would be difficult to disagree.

“Who Says I’m Uncultured?”/ “Let’s Keep the Filibuster,”The Saturday Evening Post, June 16, 1962, July 14, 1962

Remembering Titan of Journalism Pete Hamill

Legendary journalist Pete Hamill died yesterday at age 85. The illustrious writer was described as a “quintessential New York journalist” for his decades of work in The New York Post, The Daily News, The Village Voice, Esquire, The New Yorker, Playboy, and The Saturday Evening Post. He published short stories and novels too, along with a memoir and books of essays.

In newspapers, Hamill became known for his plainspoken columns, giving on-the-ground perspective of culture and justice in his home city. For this magazine, he travelled Europe in the early ’60s, sending back celebrity profiles and stories of crime and labor disputes.

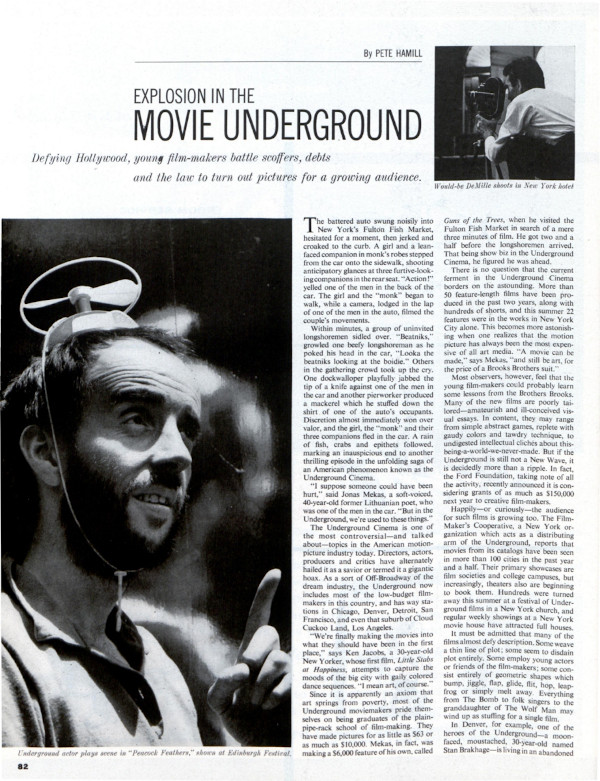

Hamill’s knack for skillfully undressing New York City was clear in one of his earliest stories for the Post, “Explosion in the Movie Underground,” printed on September 28, 1963. Years before the New Hollywood era of cinema was declared, Hamill documented the experimental filmmakers working on the streets of New York. He was skeptical of some of the “amateurish and ill-conceived visual essays” that were being produced, but he described the guerrilla directors and their makeshift moviemaking with the kind of sincere, closeup reporting that was a hallmark of his work.

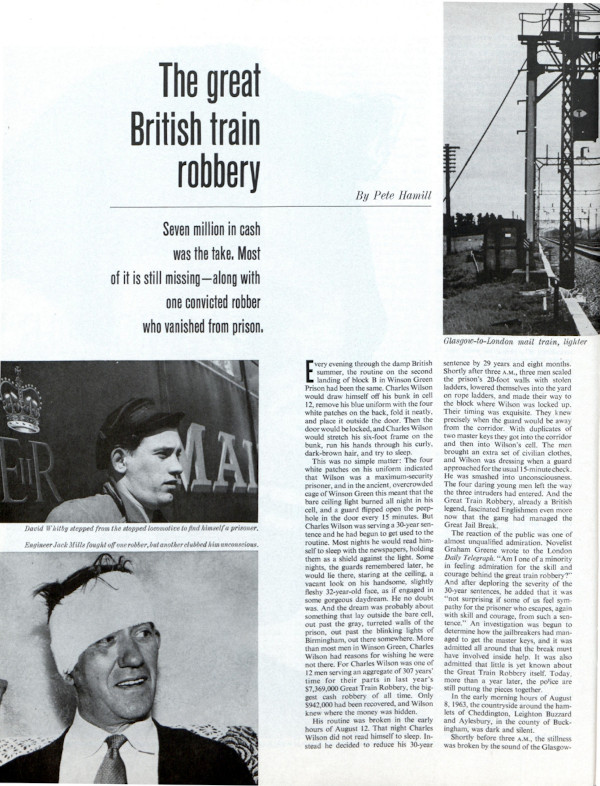

In another Post story, “The Great British Train Robbery” (September 19, 1964), Hamill covered the largest (at the time) cash robbery of all time, in which 15 men stopped a Royal Mail train and took off with more than 7 million dollars. He detailed the puzzling case of the 1963 Great Robbery and subsequent “Great Jail Break” that left British police scratching their heads and the public oddly impressed and intrigued.

Journalists and editors mourned Hamill’s passing. New York Daily News columnist Mike Lupica tweeted “As Pete once said of another New Yorker, it’s like a hundred guys just left the room,” and former New York Times writer Clyde Haberman tweeted “the world just became a far less interesting place.” Daily News reporter William Sherman wrote in an e-mail that Hamill was about the fastest writer he ever saw: “He had an preternatural understanding of the city and its people from the top hats on Fifth to the longshoremen on 12th at the River. He knew how to listen, which he advised us beginners as most important.”

In a phone call, Gay Talese recalled meeting Hamill while covering prizefighter José Torres in the late ’50s. “I’ve been living in New York for 75 of my 88 years,” he said. “I’ve known so many different writers, from poets to playwrights to journalists, and Hamill was a combination of all of those things, and he had the capacity for and time for friendship. I felt he was one of my best friends.” Talese said that Hamill’s life crisscrossed the lives of both the writing profession and nightlife: “I knew him when he was and wasn’t drinking and I couldn’t tell the difference because he was always a nice guy … he lived an extraordinary life.”

Hamill expressed his opinions on the Post in no uncertain terms soon after it folded in 1969 in a column in The Village Voice. He had visited the deserted offices on Lexington Avenue and gave a close account of the magazine’s downfall: criticism coupled with credit where credit was due for what he saw as the interesting work done in the ’60s. “At the end,” he wrote, “with the magazine collapsing around them, the Post editors finally saw fit to commission Norman Mailer to write something for them. It will never be printed by the Post.”

Hamill’s journalistic world of pounding out copy on a typewriter and throwing cigarette butts on the floor may be long over, but his intense passion for the truth, and his tendency to take to the streets to find it, is a lasting inspiration in every newsroom.

Featured image by David Shankbone, edited via the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license, GNU Free Documentation License, Version 1.2.

Remembering the Fallen of World War II

One of the most searing scenes of the 75th Anniversary of D-Day ceremonies last year was at the Normandy American Cemetery on the bluff overlooking Omaha Beach. Beautiful in its way, the grass in the 172.5 acres so green it might be in a Technicolor movie, the chalk white crosses and Stars of David on the graves — more than 9,380 — lined up in a symmetry that is breathtaking.

Beneath each cross and star lies a fallen serviceman, a G.I. we honor — every day, I hope, but especially on Memorial Day, the day set aside each year to remember the fallen. Rightly so, as the inscription on one marker puts it:

Into the great mosaic of victory

This priceless jewel was set.

So, too, the fallen in the Luxembourg American and Memorial Cemetery — 50.5 acres in Luxembourg, with 5,076 graves — one of the white crosses there marking the final resting place of General George S. Patton, “Old Blood and Guts.” He led his Third Armored Division 100 miles on icy roads in bitter cold weather in December 1944 to break the German encirclement of Bastogne in The Battle of the Bulge.

The deadliest U.S. battle of World War II, fought when the war in Europe was supposed to be over.

The surprise German attack had just started the day I approached the entrance to the Chicago Daily News Building on December 18, 1944, in hopes of getting a job as a copygirl at the Chicago Daily News. The Allied retreats each day, before the eventual advances, made up the headlines my first weeks there. Newspapers were all around me, editions delivered by copyboys coming up from the press room with the latest edition every couple of hours, distributing them to the various news desks and editors. Big black headlines were followed by stories with the details, notably the siege of Bastogne, which the Germans surrounded early on in the fighting.

Because the German attack pushed a long, deep curve in the Allied lines before the tide turned, it came to be known as The Battle of the Bulge. The daily battles, artillery shellings, and tank attacks left those rows of white markers in the Luxembourg American and Memorial Cemetery.

The war in the Pacific was equally costly.

It came into my life the morning of February 1. When I came to work I was told not to report to my usual post at the city desk but to go to a far corner of the city room, a square of four empty desks. On the cleared top was a stack of copy paper, a pair of scissors, a glue pot, and a streamer of Associated Press (AP) copy.

The streamer was not a story but a list of names of the men the Allies had just rescued from a Japanese P.O.W. camp in the Philippines — a military operation so dramatic, daring, and dangerous it came to be known as “The Great Raid.” A raid so dramatic, daring, and dangerous that John Wayne led the rescue mission in the 1945 film Back to Bataan. In a story in the late edition, AP put it this way:

SIXTH RANGER BATTALION CAMP, LUZON — (AP) — There is a long, dusty, twisting land near here which should become a war monument, for today it bridged two worlds. It leads across the plain toward the death camp where 513 prisoners of war were rescued by American Rangers and Filipino guerrillas.

To get the names of the rescued men out to their loved ones as quickly as possible, AP was listing them as they received them, not taking time to put them in alphabetical order. That was what I was to do.

I cut the names of the men apart, long narrow strips, and laid them out on the desk top. When a deadline approached, I reached for the glue pot and made a wide strip down the center of a sheet of copy paper, and stuck the names down. I remember that while they were secure, the glue did not reach the ends … and I can still see those ends curling up.

Copyboys would come for the list for the next edition and regularly bring me a new AP streamer with its list of names.

I finished just after lunch and settled in at my regular post at the city desk, ready to answer calls of “Copy!” and take stories to the copydesk or get clips from the library. And when things grew quiet late in the afternoon, I had time to read the latest edition, just dropped off at a nearby news desk.

Amongst all the happy photos of local families beaming at family pictures of their rescued sons or husbands, boyfriends or brothers, were the first stories about the men and the toll their years in the POW camp had taken.

There were those so weak, emaciated, a Ranger could carry two men on his back. Some limped from beriberi. The legs of some were scored by tropical ulcers and other diseases, and there were those who looked up helplessly from litters.

They talked in low tones of Japanese brutality and the Death March of Bataan, of the final terrifying week of bombing and bombardment that hit Corregidor, of men dying like flies, of disease, of ten hours daily in prison camps, under the hot sun in fields, or waist high in water of rice paddies under hard eyes, of frequent beatings and shootings.

They recalled when 10,000 men at the Cabanatuan prison camp used to spend all day strung out in line for a canteenful of water from one of the camp’s four spigots.

Now, they lined up for a supper of boned chicken, peas, beans, fruit salad, jam and cocoa — a veritable banquet after the starvation fare of the Japanese prison camp.

Invited to ask for more and eat all they want, one of the men said, “Where we come from they put you in the guardhouse if you asked for more.”

It was only with time that I realized each name on those AP streamers — soon a narrow slip of paper on the cleared top of the dark green metal desks — was the name of a man who had not only survived a Japanese POW camp but the Bataan Death March, one of the most horrific episodes of the war. So named because 10,000 of the 76,000 men who had surrendered when Bataan fell to the Japanese died during the five-day, forced march —66 miles in jungle heat to the Japanese prison camps. Some guards took the men’s canteens and emptied them of water so they would have nothing to drink. Others killed, bayoneted, and beat men who tried to get a drink from the gushing artesian wells they passed.

And so, while I don’t remember the names I alphabetized that day, I remember the men whose names were on those narrow slips of paper with the ends curling up — what they endured in their service to their country.

One of the survivors, Glenn Frazier, gave an account of the horrors in the Ken Burns documentary for PBS The War. It appears in the companion book, Frazier saying:

I saw men buried alive. When a guy was bayoneted or shot, lying in the road, and the convoys were coming along, I saw trucks that would just go out of their way to run over the guy in the middle of the road. And likewise the rest of the trucks, and by the time you have fifteen or twenty trucks run over you, you look like a smashed tomato. And I saw people who had their throats cuts because [the Japanese] would take their bayonets and stick them out through the corner of their trucks at night and it would just be high enough to cut their throats. And I saw men beaten with a rifle butt until there just was no more life in them. I saw Filipino women [who tried to bring us food or water] cut. Their stomachs were cut open. Their throats were cut. I saw Filipino and Americans beheaded just with one swipe of a saber.

An officer who’d been keeping track of the cut-off heads he saw as he passed stopped counting at twenty-seven lest he go mad.

Soon the headlines moved on again. This time, to Iwo Jima. The Marines landed there February 19.

The flag raising atop Mount Suribachi as they took control of part of the island would become one of the most famous pictures of World War II, or any war, for that matter. It would win the Pulitzer Prize for AP photographer Joe Rosenthal, go on to become a huge bronze statue — the centerpiece of the United States Marine Corps War Memorial in Arlington, Virginia — and an array of U.S. postage stamps through the years.

Many a headline reported the battle, the progress, the fierce resistance the Marines encountered, before the fighting ended March 26. But it was only when I read the book Flags of Our Fathers by James Bradley, son of one of the flag-raisers, that I fully appreciated what the Marines faced.

“The Marines fought in World War II for forty-three months,” Bradley said. “Yet in one month on Iwo Jima, one third of their total deaths occurred. They left behind the Pacific’s largest cemeteries: nearly 6,800 graves in all, mounds with their crosses and stars.”

Someone chiseled these words outside the cemetery on Iwo Jima:

When you go home

Tell them for us and say

For your tomorrow

We gave our today

Featured image: Marines raising the American flag on Iwo Jima, February 23, 1945 (photo by Joe Rosenthal / public domain)

Numbed by Media: Newspaper Reading as a Dissipation

Over 16,000 newspapers were feeding America’s hunger for news in 1900. People were becoming better informed, but Post editors worried the constant exposure to violence, injustice, and scandal in the papers was making Americans incapable of outrage.

The first peril of careless newspaper reading is that of being morally hardened by constant contact with the physical and spiritual evils of the world, without being called upon to any action with regard to them.

It requires a notable degree of moral culture to keep from becoming “used to” such things; and there are few things worse for us than to grow accustomed to men’s sufferings and their sins, so that these no longer evoke pity, or indignation, or any other emotion in us.

The great minds are those which show the least disposition to become familiar with wrong, so as not to feel indignation every time they see it. They have a moral freshness which is our right and normal condition. They never “get used to” good or evil.

It is very hard for us to keep this freshness of moral impression in our daily contact with what the newspaper tells us of the world’s evil. It is even harder not to be deceived as to the comparative weight of evil and goodness in the world. The newsgatherer is drawn naturally to the former.

—“Newspaper Reading as a Dissipation,” Editorial by Robert Ellis Thompson, March 11, 1899

This article is featured in the March/April 2019 issue of The Saturday Evening Post. Subscribe to the magazine for more art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

Featured image: Shutterstock

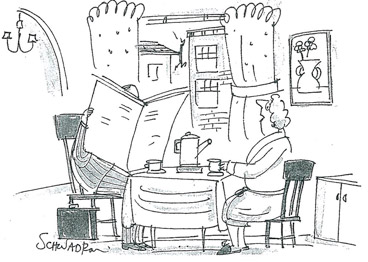

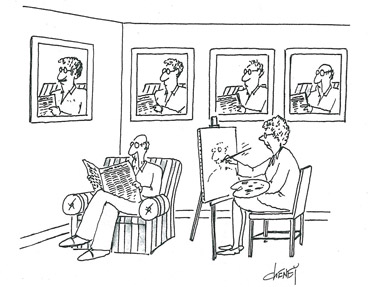

Cartoons: Newspapers

Sure, you like your e-reader or tablet now. But can you use it to line a birdcage? Can you rustle it irritatingly when your spouse annoys you? We think not.

"If newspapers disappear, how will I ignore you in the morning?"

"Sorry, dear, I thought you’d finished reading the paper."

"... and you needn’t be giving your paper those sarcastic twitches!"

"Gerald, how would I describe you if I ever had to report you to the missing persons bureau?"

"That's not what Dr. Jefferies meant by 30 minutes on the treadmill’!"