The Saturday Evening Podcast: The Days Before Pearl Harbor

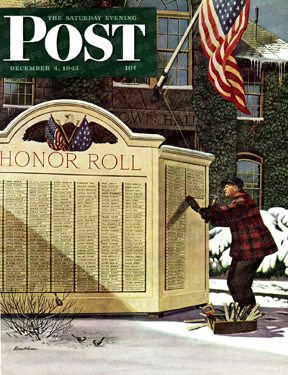

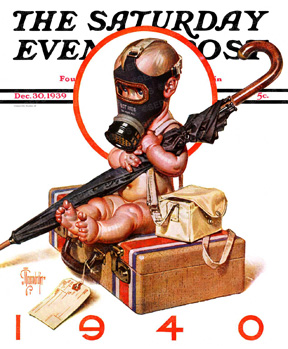

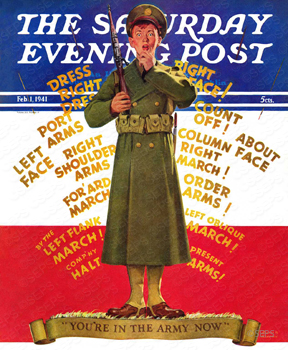

The attitude of pre-World War II America was quite different from the heroic era of the war years. The U.S. was still a modest, isolationist nation, with limited industry, a tiny army, and the hope that, by minding its own business, it could remain untouched by war. Although the December 6, 1941, issue of the Post shows a country at peace, the signs that war was spreading are evident throughout its pages.

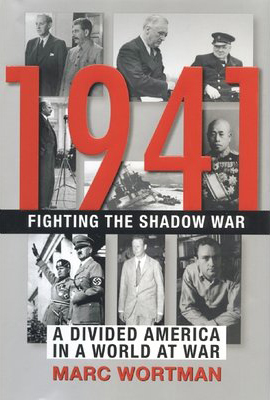

In this podcast, Jeff Nilsson interviews historian Marc Wortman. In his book 1941: Fighting the Shadow War, Wortman reveals the depths to which the United States had already been involved in World War II before the attack on Pearl Harbor. Dispelling the myth that the United States was a neutral nation caught flat-footed by the Japanese attack, Wortman shows how the U.S., through military deployments, the Lend-Lease Program, and actual confrontations with Axis forces, was “neck-deep in the war before December 7.”

Sound files excerpted in the podcast:

- News announcement of the Pearl Harbor attack, December 7, 1941, station unidentified

- NBC radio announcement of the attack on Pearl Harbor

- Eleanor Roosevelt speaking for the Pan-American Coffee Bureau Series, episode 11, December 7, 1941

- “Boogie Woogie Bugle Boy,” Andrews Sisters, 1941

- G. Wodehouse’s second broadcast on Reich Broadcasting Service, July 9, 1941

- “Moonlight Cocktail,” Glenn Miller Band, 1941

- “World News Today,” CBS radio, December 6, 1941

- Winston Churchill speech to Parliament, July 14, 1941

- Charles Lindbergh, America First Committee speech, Des Moines, Iowa, September 11, 1941

- “Chattanooga Choo Choo,” Glen Miller Band, 1941, the top song in the U.S. on December 7, 1941

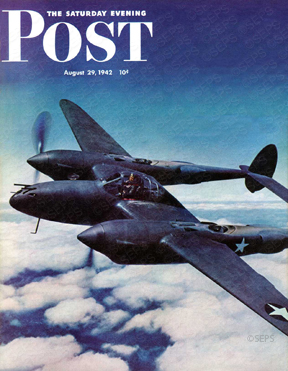

Featured image: By United States Air Force [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

News of the Week: Christmas in Connecticut, Culinary Lawsuits, and Comfort Food

Three Movies You Should Watch

Yes, it’s December, and the holiday season has officially begun. We all know what the greatest Christmas movies are. They’re the ones we’ve all watched a million times and watch every year: It’s a Wonderful Life (my favorite movie of all time), Miracle on 34th Street, A Christmas Story, Holiday Inn, the 97 versions of A Christmas Carol, and all of those TV specials where noses glow red and grinches steal. But I’d like to point you to three Christmas movies that are pretty terrific that you might not be aware of:

- Christmas in Connecticut (1945). This film, like all of the films on this list, is starting to become more known and popular thanks to annual showings on Turner Classic Movies. It stars Barbara Stanwyck as a Martha Stewart-ish columnist who actually knows nothing about the home or cooking and is only pretending to be married with a child. When her boss (Sydney Greenstreet) and a war hero (Dennis Morgan) come to her home for Christmas, chaos ensues! A really fun film.

- Holiday Affair (1949). A Christmas movie with hard-boiled Robert Mitchum might not scream “festive” at first, but he’s actually quite good in this comedy-drama. He plays a department store salesman who falls in love with customer Connie (Janet Leigh), which is a problem because she’s engaged to someone else. (Gordon Gebert, who plays Leigh’s young son, talked about his role at a screening in 2014).

- It Happened on Fifth Avenue (1947). Wouldn’t it be fun to break into a mansion owned by a millionaire who spends the holidays someplace else and have complete run of the place with your friends and your dog? That’s the premise of this comedy starring Don DeFore, Victor Moore, Ann Harding, and Alan Hale, Jr.

You can find out when these movies will be shown this month by checking out TCM’s schedule.

In This Corner …

I’ve been keeping you up to date on what’s going on with former America’s Test Kitchen host Christopher Kimball and his new venture, Milk Street Kitchen. The latest news is a plot twist to say the least.

The company that owns America’s Test Kitchen and Cook’s Illustrated has filed a lawsuit accusing Kimball of many things since he left to form the new company, including the poaching of employees and transferring to himself relationships with vendors. Now, lawsuits happen every single day, and it’s not really surprising. What is surprising, however, is that ATK has created an entire website devoted to the lawsuit! It explains why they’re suing, has the text of the complaint, and even has a chronology of what transpired, with copies of Kimball’s emails that supposedly show he did something illegal. This is all pretty stunning (I don’t think I’ve seen anything like it before), and like a lot of people I’m curious about how the site will affect the legal proceedings. It must be doubly odd because Kimball still hosts the weekly ATK radio show.

By the way, if you noticed, the URL of the lawsuit’s site is WhyWeAreSuingChristopherKimball.com. It can’t be a good feeling to see a website address that has your name and the word suing in it.

RIP Ron Glass, Fritz Weaver, Ralph Branca, Grant Tinker, and Jim Delligatti

By Raven Underwood [CC BY 2.0], via Wikimedia Commons

Fritz Weaver was an acclaimed actor on the stage, in film, and on television. He appeared in such stage plays as Baker Street (playing Sherlock Holmes), Child’s Play, The Chalk Garden, and Angels Fall. He made his film debut in 1964’s Fail-Safe and also appeared in Marathon Man, Black Sunday, Creepshow, and the Pierce Brosnan remake of The Thomas Crown Affair, along with TV shows like Armstrong Circle Theatre, The Man from U.N.C.L.E., Mission: Impossible, The Twilight Zone, Gunsmoke, Mannix, The X-Files, Law & Order, and the miniseries Holocaust. He passed away last weekend at the age of 90.

Bobby Thompson hit “The Shot Heard ’Round the World” in the final game of the 1951 National League championship series in which the New York Giants beat the Brooklyn Dodgers. The pitcher who gave up that famous home run, Ralph Branca, passed away last week. He was 90.

Grant Tinker was the head of MTM Enterprises in the 1970s. MTM stands for Mary Tyler Moore, whom Tinker was married to for several years. As head of the production company, he was responsible for shows like The Mary Tyler Moore Show, The Bob Newhart Show, Rhoda, and Phyllis.

As if that wasn’t enough, in the 1980s he helped save NBC by bringing us The Cosby Show, Cheers, Family Ties, The Golden Girls, Miami Vice, Remington Steele, and Night Court. He was also in charge of the TV department of the advertising agency McCann Erickson (which you might remember from Mad Men) in the ’50s and later was an executive with Benton and Bowles, where he got a sponsorship for his client Procter & Gamble on The Dick Van Dyke Show, where he met Moore. I should add that over the last five decades, he also had a hand in shows like Marcus Welby, M.D., I Spy, It Takes a Thief, Dr. Kildare, and Get Smart. That’s quite a track record.

Tinker passed away Wednesday at the age of 90.

Jim Delligatti? He invented the Big Mac! He passed away this week at the age of 98.

What Does Your Smartphone Say about You?

Do you use an iPhone? You might be a liar.

That’s one of the findings of this study from England’s Lancaster University. Researchers concluded that iPhone users tend to be female, younger, and extroverted, while Android users tend to be male, older, more honest, and more agreeable.

In related news, an ex-Google exec says that we’re all addicted to our phones and it might be time to kick the habit. If any of these cartoons look like a scene from your life, you might have a problem. Another good way to check if you’re addicted: Do you keep your phone with you all the time, even when you’re eating holiday dinner with your family? There you go.

La La Land

Sometimes a film comes along and people say, “They don’t make movies like this anymore.” But it’s usually not true. Whatever movie they’re talking about has probably been done a dozen times recently.

La La Land, the new film starring Ryan Gosling and Emma Stone, can really be described that way, though. He plays a pianist who falls in love with an aspiring actress in Los Angeles. That makes the film sound rather dull, so here’s a trailer that shows what the movie is all about. It seems to be a modern-day homage to the musicals of the ’40s and ’50s. I can imagine this being shown on Turner Classic Movies in 40 years.

I’m looking forward to this more than I am any Star Wars or Marvel movie. It opens in selected cities on December 9 and elsewhere later in the month.

This Week in History

Samuel Clemens Born (November 30, 1835)

Was the young Clemens — a.k.a. Mark Twain — an amusing scoundrel, a storytelling genius, or both?

Rosa Parks Arrested (December 1, 1955)

The National Archives has a fascinating record of the arrest of the civil rights icon after she refused to move to the back of a bus in Montgomery, Alabama.

Senate Votes to Censure Joseph McCarthy (December 2, 1954)

The senator’s attack on the U.S. Army was too much for his Congressional colleagues.

National Comfort Food Day

Comfort food is a form of nostalgia. It’s the food that reminds us of our childhoods or a good time in our lives. It’s a memory that figuratively warms us and foods that may literally warm us (even if those foods happen to be cold). Music and movies and TV shows and relationships can take us back to certain times in our lives, and so can food.

This Monday is National Comfort Food Day, and since it’s the holiday season, it’s a food holiday whose placement on the calendar actually makes sense. I don’t know what your personal favorite comfort foods are, but maybe they could include this Cowboy Beef and Black Bean Chili or this Rich Roasted Tomato Soup. Or maybe it’s a Red Velvet dessert that warms your heart. Or maybe a Classic Chicken Soup is all you need.

I like all those things. Which probably says a lot more about me than any smartphone could.

Next Week’s Holidays and Events

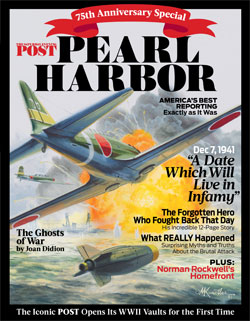

Pearl Harbor Day (December 7)

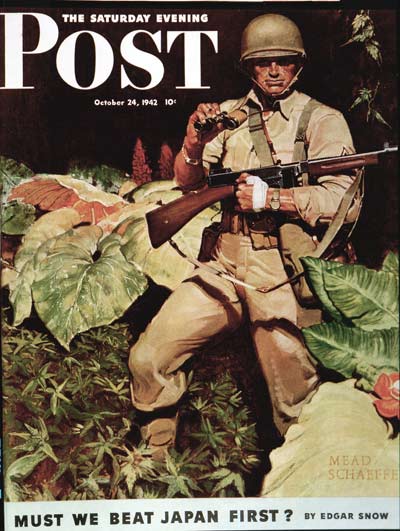

It’s the 75th anniversary of the attack on Pearl Harbor. Here’s an excerpt from a feature that ran in The Saturday Evening Post in October 1942, part of our Pearl Harbor special edition available in bookstores now.

Christmas Card Day (December 9)

Facebook may be hurting Christmas card sales, but maybe it’s something you should start doing again. I still send them out every year. So go out and buy some real cards and actually mail them to those you love, instead of sending a text or social media post to wish someone happy holidays.

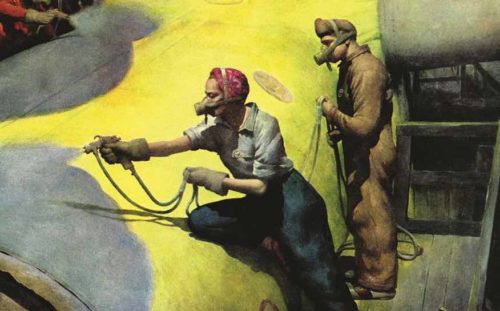

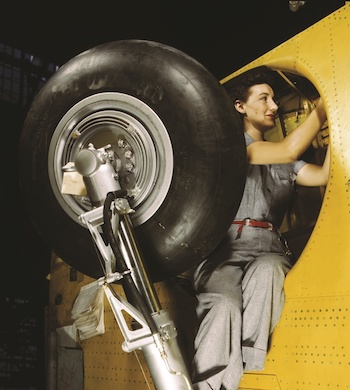

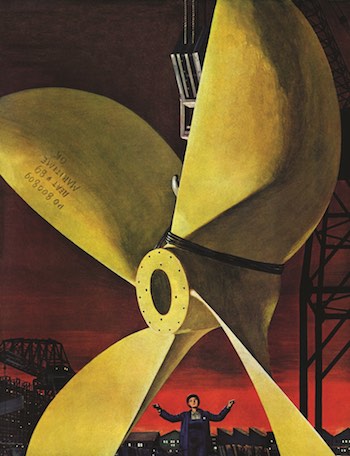

Surprise! Women Do the Heavy Lifting During World War II

After the bombing of Pearl Harbor in 1941, men went off to fight. Women became essential on the factory floor as industrial production soared to support the war effort. Read this excerpt, Surprise! Women Do the Heavy Lifting, from the print publication, Pearl Harbor: 75th Anniversary Special.

Originally published on May 30, 1942

Fuming over the sneak bombing of Pearl Harbor, Mrs. Clover Hoffman, diminutive and spirited mother of Cliff and Charlotte, twins aged 3½, reached a decision important in the task of defeating the Japs and the Nazis. Resigning her job as waitress in a San Diego restaurant, and parking the twins with her mother, Mrs. Hoffman presented herself at the employment office of the Consolidated Aircraft Corporation.

“I want to work on a bomber,” she told Mrs. Mamie Kipple, assistant employment director in charge of hiring the women who work in the company’s two sprawling plants.

“Why do you want to work on a bomber?” asked Mrs. Kipple.

“That’s something I can do to help bring Harry back.”

“Who is Harry?”

“My husband. He’s machinist’s mate on a destroyer at Pearl Harbor.”

“Have you ever worked in a factory?”

“No; but I can learn, if you’ll give me a chance.”

Like other aircraft manufacturers of Southern California, where half the country’s bombers and fighters first take wing, the Consolidated management, which began employing women for factory work last September, had a soft spot for Pearl Harbor wives and widows. The following day, Mrs. Hoffman, in trim blue jumperalls, was busily sorting and testing small parts in the blister department. A blister is a transparent plastic turret from which gunners aboard the huge

flying boats and heavy-bombardment bombers fight off enemy attackers.

Within a month, with nimble fingers and a will to learn, Mrs. Hoffman was rated as a veteran factory hand among the thousands of “Keep-’Em-Flying girls” helping to build planes in West Coast aircraft plants, strictly a man’s world until eight months ago. When they first appeared on the assembly benches, the women were “the lipsticks” to the men. Workers and bosses alike said, as did hard-boiled Bert Bowler, plant manager for Consolidated, “The factory’s no place for women.”

Now Bowler says, “They’re better than men for jobs calling for finger work. They will stick on a tedious assembly line long after the men quit. Women can do from 22 to 25 percent of the work in this plant as efficiently as men.” At the Inglewood plant of North American Aviation, Inc., with 1,100 women on the payroll, M.E. Beaman, industrial-relations director, goes further than that. “Women can do approximately 50 percent of the work required to construct a modern airplane,” he estimated. Douglas Aircraft, which started late in the employing of women in the factory, expects to have 40,000 on the payrolls of its four plants by the end of 1942. After a study of British plants, Douglas engineers think women may have to do 60 percent of the building of planes before the aircraft plants reach all-out production. Lockheed and Vega, with 2,000 women filtered into groups working on everything from radio wiring to tubing-detail assemblies — plumbing, in plain English — are hiring and training housewives and girls fresh out of school at the rate of 200 a week. Vultee, which pioneered the use of women in aircraft building one year ago, rates them as indispensable. At Seattle, the Boeing Aircraft Company launched courses for women factory hands on the first of the year. In Midwestern cities, all the major Pacific Coast plane builders except Lockheed and Vega are rushing supplementary plants in which approximately 50 percent of the work will be handled by women. By the end of the year, it is estimated that 200,000 housewives will have left their homes for the aircraft factories.

“If they’re not wives when they are hired, they soon will be,” laughed Mrs. Kipple. “Around San Diego the saying is, ‘If you want to find a husband, get a job at Consolidated.’ That’s how I found mine.”

“Work on planes is a natural for women,” a Consolidated engineer explained. “There are more than 101,000 separate and distinct parts in one of our bombers, counting rivets, and most of them are so light in weight that women can assemble and test them as easily as men. Better, in some cases.”

“Every woman we train for some simple step in aircraft work releases a man for a job calling for more experience,” pointed out Aileen Carmichael, assistant personnel director, who started as a clerk on the night shift, learned mechanics in a trade school, then took charge of hiring women for the new Vega factory. “You ought to talk with some of the girls on the assembly lines and see why they are here and what they say about the work. It will give you a lift.”

So I did. I talked with dozens of them above the din of the riveting and stamping machines. It was an eye opener, not only in wartime industrial readjustment but in devotion to purpose. In every plant, foremen who once dreaded the influx of “the lipsticks” told with enthusiasm how mixing women workers in the teams had stepped up both morale and the output of planes.

Kitchen Technique

“The main problem with women,” one foreman told me, “is to get them to take it easy for a while and not rush and worry about the work. So I tell ’em, ‘Just imagine you’re in a kitchen baking a cake instead of in a factory building a bomber.’

“Women workers handle the repetitive jobs without losing interest or a letdown in efficiency,” he continued. “I guess it’s because this is win-the-war work for them, while men are eager to get ahead personally. We team the women with the men because they learn faster from men than from women.”

In the Vega sheet-metal department, I watched Mrs. Mary Rozar, barely 5 feet tall, dressed in slacks and blouse, protected by a leather apron, absorbed in smoothing the edges of odd-shaped parts for Flying Fortresses. Mrs. Rozar appeared at the employment office when the Vega management announced it would give preference to wives and widows of men in service at Pearl Harbor and in the Philippines.

“I’m not a Pearl Harbor widow,” she told Miss Carmichael, apologetically, “but I’m a Pearl Harbor mother. My Johnny boy lost his life on the Arizona. I have another son, Earl, somewhere in Alaska with the United States Army. I want to help build planes.”

Upstairs, where hundreds of girls deftly connect and mark wires for the electrical-control assemblies, I noticed an attractive young woman with much poise who came in with the second shift and hit her stride in nothing flat. The foreman introduced her as “Jerry” Patterson.

“You don’t look like a factory worker,” I said.

“Maybe I don’t, and maybe I’m not, but I can put these assemblies together,” she replied. Her husband, Capt. Russell Patterson, was on Bataan Peninsula under General Wainwright, she said. The young Pattersons were living in Chicago, where he was an attorney when called to the service early in 1941.

“I tried working in a dentist’s office first,” she said. “That gave me no satisfaction, so I came out here, took the tests, and they put me to work on these assemblies. I haven’t heard from Russell, and I can’t get word to him, but every night I write half a page of a letter to tell him what I did that day to help finish a plane. I’m saving the letters for the day when General MacArthur goes back to the Philippines.”

At the Lockheed factory, one of the plant’s best woman spot welders is Mrs. Prisalla Maury. Her father is Col. Paul D. Bunker, in command of a coast-artillery unit at Fort Mills, “topside” of Corregidor. Across the narrow strait on the Bataan Peninsula, her husband, Major Thompson B. Maury III, was in a field-artillery unit that repeatedly hurled back the Japs. To most women, that might seem enough to do to beat the Japs. Not for Prisalla Maury, who, trained as a chemist, goes to the factory each morning, leaving four red-headed young Maurys, Richard, 6, Ann, 5, William, 2½, and Sarah, 1, at home with her mother.

“They need planes over there,” she declared. “This is the best thing I can do to help get them there.”

“She’s doing her share all right,” added John Ferguson, group leader of the spot-welding unit to which Mrs. Maury belongs. “She likes to stand on her own. If any man tries to help her, she shoos him off in a hurry.”

Two-Way Whistle

At Douglas, shortly after the first woman appeared on the assemblies, the men began whistling when an attractive young girl in bright-colored slacks and blouse walked down the aisle. The women held an indignation meeting. The following day, as the men spewed out of the plant for lunch, the girls were waiting for them. Every time a handsome young buck came through the door, they whistled and shouted, “Look at Tarzan! Isn’t he wonderful? Oh, Handsome!”

The whistling in the factory ended abruptly.

“Women are in the airplane plants to stay,” predicted Mrs. Kipple at Consolidated. “Our idea at first was they would step into the men’s shoes as the men were called for military service. They would build the planes and they would be the earners, until the men came back. But there will be a lot of jobs in the factory that the men will never get back. The women have demonstrated they can handle them better.”

Pearl Harbor Remembered: I Fly for Vengeance

Excerpted from a serialized article originally published October 10–24, 1942

This feature is included in Pearl Harbor: 75th Anniversary Special, a print publication highlighting articles, picture galleries, and editorials that appeared in The Saturday Evening Post before, during, and after December 7, 1941. This special edition is available for sale a shoptthepost.com.

You would damn well remember Pearl Harbor if you had seen the great naval base ablaze as we of Scouting Squadron 6 saw it from the air, skimming in ahead of our homeward-bound carrier. The shock was especially heavy for us because this was our first knowledge that the Japs had attacked on that morning of December 7. We came upon it stone cold, each of us looking forward to a long leave that was due him.

It wasn’t that we pilots didn’t sense the tension that gripped the Pacific. You could feel it everywhere, all the time. Certainly the mission from which we were returning had the flavor of impending action. We had been delivering a batch of 12 Grumman Wildcats of Marine Fighting Squadron 211 to Wake Island, where they were badly needed. On this cruise, we had sailed from Pearl Harbor on November 28 under absolute war orders. Vice Admiral William F. Halsey Jr., the commander of the Aircraft Battle Force, had given instructions that the secrecy of our mission was to be protected at all costs. We were to shoot down anything we saw in the sky and bomb anything we saw on the sea. In that way, there could be no leak to the Japs.

There was no trouble at all, and we headed back from the Wake errand with a feeling of anticlimax — all of us, that is, except one young ensign. The Wildcats had taken off for Wake at a point about 200 miles at sea, escorted by six scout dive bombers, and this ensign was in the escort. The mist was heavy, and once, looking down through it, he saw three ghostlike shapes that resembled ships. Immediately the scouting line closed in for a search, but found nothing. However, the ensign, rightly or wrongly, was convinced to the end of his life — not many days away — that what he had seen was Japanese warships. If he did, and if mist hadn’t hampered the search, the course of history might have been changed. As we steamed back toward Pearl Harbor, the rest of us gradually came to look upon the incident as just another scare.

Bad weather delayed us and we were getting home on Sunday instead of on Saturday, as planned. While the engines were being warmed up on the flight deck early on Sunday morning, my rear-seat gunner and radioman, W.C. Miller, a lad of 21 or 22, had a word for me as he stood on the wing and helped adjust my radio cord. He said that his four-year tour of duty was to end in a few days and that there was “something funny” about it.

“Mr. Dickinson,” he went on, “out of 21 of us fellows that went through radio school together, I’m the only one that hasn’t crashed in the water. Hope you won’t get me wet today, sir.”

“Miller,” I replied, “next Saturday we all go home for five months, so probably this will be our last flight together. Just stick with me, and the first thing you know we’ll be on the Ford Island runway. That’s all we’ve got to get by — this morning’s flight.”

Miller and I were both North Carolinians and had been flying together since I joined the squadron in April 1941. He was dependable and cool, the kind of man I like to have at my back when I’m in the air.

He climbed into the rear cockpit, faced the tail in his regular position, and the squadron was off; 18 planes flying in nine 2-plane sections; 72 eyes to scrutinize a 100-mile-wide corridor of ocean through which our carrier and its accompanying destroyers could follow safely. It was 6:30 a.m. When the squadron reached 1,000 feet, the prows of the vessels seemed to be making chalk-white V’s on slate. As we took off, the task force was 210 miles off Barber’s Point, which is at the southwest tip of the island of Oahu. Barber’s Point is about 10 miles west of Pearl Harbor.

Flying Straight into History

Several times on the way in I had Miller take a bearing with his direction finder on a Honolulu radio station, to be sure we were on the prescribed course. The last time he did it, it was about five minutes past eight and we were 25 miles or so off Barber’s Point. It seems amazing now, but they were still broadcasting Hawaiian music from Honolulu.

I noticed a big smoke cloud near my goal, then saw that it was two distinct columns of smoke swelling into enormous cloud shapes. But I paid little attention. Smoke clouds are familiar parts of the Hawaiian landscape around that season, when they burn over vast fields after harvest.

Four ships lay at the entrance to Pearl Harbor, one cruiser and three destroyers. I could tell they were ours by their silhouettes. Ahead, well off to my right, I saw something unusual — a rain of big shell splashes in the water, recklessly close to shore. It couldn’t be target practice. This was Sunday, and anyway the design they made was a ragged one. I guessed some coast-artillery batteries had gone stark mad and were shooting wildly.

I remarked to Miller, through my microphone, “Just wait! Tomorrow the Army will certainly catch hell for that.”

When we were scarcely three minutes from land I noticed something that gave a significant and terrible pattern to everything I had been seeing. The base of the biggest smoke cloud was in Pearl Harbor itself. I looked up higher and saw black balls of smoke, thousands and thousands of them, changing into ragged fleecy shapes. This was the explanation of the splashing in the water. Those smoke balls were antiaircraft bursts. Now there could be no mistake. Pearl Harbor was under air attack.

I told Miller and gave him the order, “Stand by.” Ensign McCarthy’s plane was 300 or 400 yards to my right. As Mac closed in, I was charging my fixed guns. I gestured, and he charged his. Mac signified, by pointing above and below, that he understood the situation.

When we were probably three miles from land, we saw a four-engined patrol bomber that we knew was not an American type. It was a good 10 or 12 miles away. Mac and I started for him as fast as we could go, climbing. We were at 1,500 feet, he was at about 6,000 feet. He ducked into the smoke cloud which loomed like a greasy battlement.

We darted in after him and found ourselves in such blackness we couldn’t see a thing. Not even then were we aware that the source of the smoke in which we hunted was the battleship Arizona.

Mac and I came out and headed back for Barber’s Point for another look. In a few minutes we were over it at 4,000 feet, flying wing to wing. A glance to the right at McCarthy’s plane was almost like seeing Miller and myself in a mirror — there they were, in yellow rubber life jackets and parachute harnesses, and almost faceless behind black goggles and radio gear fixed on white helmets. Mac’s gunner, like mine, was on his seat in his cockpit, alert to swing his twin machine guns on the ring of steel track that encircled him.

Things began happening in split-second sequences. Two fighters popped out of the smoke cloud in a dive and made a run on us. Mac dipped his plane under me to get on my left side, so as to give his gunner an easier shot. But the bullets they were shooting at me were passing beneath my plane. Unlucky Mac ran right into them. I put my plane into a left-hand turn to give my gunner a better shot, and saw Mac’s plane below, smoking and losing altitude. Then it burst into yellow flame. The fighter who had got Mac zipped past me to the left, and I rolled to get a shot at him with my fixed guns. As he pulled up in front of me and to the left, I saw painted on his fuselage a telltale insigne, a disk suggesting, with its white background, a big fried egg with a red yolk. For the first time I confirmed what my common sense had told me; these were Jap fighters, Zeros.

I missed him, I’m afraid.

A Casualty of the Zeros

Those Zeros had so much more speed than I did that they could afford to go rapidly out of range before turning to swoop back after McCarthy. Four or five more Zeros dived out of the smoke cloud and sat on my tail. Miller was firing away and was giving me a running report on what was happening behind me.

It was possibly half a minute after I had seen the Jap insigne for the first time that Miller, in a calm voice, said, “Mr. Dickinson, I have been hit once, but I think I have got one of them.”

He had, all right. I looked back and saw with immense satisfaction that one of the Zeros was falling in flames. In that interval, watching the Jap go down, I saw McCarthy’s flaming plane again, making a slow turn to the right. Then I saw a parachute open just above the ground. I found out later it was Mac’s. As he jumped he was thrown against the tail surface of his plane and his leg was broken. But he landed safely.

Jap fighters were behind us again. There were five, I should say, the nearest less than 100 feet away. They were putting bullets into the tail of my plane, but I was causing them to miss a lot by making hard turns. They were having a field day — no formation whatever, all of them in a scramble to get me, each one wildly eager for the credit.

One or more of them got on the target with cannon. They were using explosive and incendiary bullets that clattered on my metal wing like hail on a tin roof. I was fascinated by a line of big holes creeping across my wing, closer and closer. A tongue of yellow flame spurted from the gasoline tank in my left wing and began spreading.

“Are you all right, Miller?” I yelled.

“Mr. Dickinson, I’ve expended all six cans of ammunition,” he replied.

Then he screamed. It was as if he opened his lungs wide and just let go. I have never heard any comparable human sound. It was a shriek of agony. When I called again, there was no reply. I’m sure poor Miller was already dead. I was alone and in a sweet fix. I had to go from a left-hand into a right-hand turn because the fast Japanese fighters had pulled up ahead of me on the left. I was still surprised at the amazing maneuverability of those Zeros. I kicked my right rudder and tried to put my right wing down, but the plane did not respond. The controls had been shot away. With the left wing down and the right rudder on and only eight or nine hundred feet altitude, I went into a spin.

I yelled again for Miller on the long chance that he was still alive. Still no reply. Then I started to get out. It was my first jump, but I found myself behaving as if I were using a check-off list. I was automatically responding to training. I remember that I started to unbutton my radio cord with my right hand and unbuckle my belt with my left. But I couldn’t unfasten my radio cord with one hand. So, using both hands, I broke it. Then I unbuckled my belt, pulled my feet underneath me, put my hands on the sides of the cockpit, leaned out on the right-hand side, and shoved clear. The rush of wind was peeling my goggles off.

I had shoved out on the right side, because that was the inside of the spin. Then I was tumbling over in the air, grabbing and feeling for the rip cord’s handle. Pulling it, I flung my arm wide.

There was a savage jerk. From where I dangled, my eyes followed the shroud lines up to what I felt was the most beautiful sight I had ever seen — the stiff-bellied shape of my white silk parachute. I heard a tremendous thud. My plane had struck the ground nose first, exploding. Then I struck the ground; feet first, seat next, head last. My feet were in the air and the wind had been jarred out of me. Fortunately, I had jumped so low that neither the Japs overhead nor the Marines defending Ewa Field had time to get a shot at me.

I had come to earth on the freshly graded dirt of a new road, a narrow aisle through the brush to the west of Ewa Field, and had had the luck to hit the only road bisecting that brush area for five miles. Except for a thorn in my scalp, my only injury was a slight nick on the anklebone, where machine-gun bullets had made horizontal cuts in my sock.

My main worry was to get out of the parachute tangle and on to Pearl Harbor to stand by for orders. Afterward, I walked and ran for about a quarter of a mile to the main road, bordered by cane fields. I knew this was the way to Pearl Harbor. There were curious tremors underfoot. Those were the bombs. It seemed, too, as if many carpets were being beaten. That was machine-gun fire. Heavier overtones came from antiaircraft batteries not far off. I could orient myself by the smoke obscuring much of the sky. The nearer and smaller column tapered to earth nearby. So I knew that there on my right hand, possibly two miles away, was Ewa Field, the Marine air base. But five miles ahead, everything was blackly curtained by smoke.

The first automobile that came along, a blue sedan about two years old, was headed my way. I stepped out and signaled by waving my white helmet. The car rolled to a stop where I stood. A nice-looking gray-haired man was driving. The woman beside him, wearing a blue-and-white polka-dot dress, was stout, cheerful, and comfortable looking. They smiled cordially.

“I’m sorry, sir,” I said, “but I must have a lift to Pearl Harbor. I’ve just been shot down.”

The man accepted the urgency in my voice without, I think, really grasping the significance of what I had said. He reached behind him and opened a door. I got into a backseat crowded with picnic things — a wicker basket brim-full of wax-paper packages; a vacuum bottle, and a brown paper bag of bananas. On the floor was a bottle wrapped in a clean dish towel. The woman half turned her head and said that it was too bad they wouldn’t have time to take me to my destination, because they were going on a picnic.

“I’m sorry, ma’am,” I said, “but you have got to take me to Pearl Harbor.”

“But our friends are waiting for us. We are bringing the potato salad and they have the chicken.”

Japanese planes droned overhead. Taking a hand myself, I told her to look.

“Japanese planes? Those?”

“Yes, ma’am.”

Suddenly she became tender and solicitous. Had I really been shot down? Was I hurt? Would I like something to eat? I told her I was thirsty. That was true enough. My mouth was so dry it was an effort for me to speak. But all they had was a bottle of whisky — it was what was wrapped in that dish towel. I didn’t take any because I figured I would have to fly again that day. By this time we were approaching a few houses and a general store in the cane fields. As far as I was concerned, the war was going to have to wait until I had a Coke.

As we started off again, Jap planes were strafing the road with machine guns and cannon. Through the rear window I could see a low-flying Jap, his guns winking like malefic jewels. He missed us, but hit a sedan 50 feet in front of us, in which another couple were riding. Riddled with tiny holes and jagged cannon slashes, the sedan careened, turned over, and landed in a ditch in a cloud of yellow dust. As we sped on, we saw other bullet-torn automobiles that had either rolled or been pushed into ditches and fields along the way.

We got to Pearl Harbor just in time to see the big dive-bombing attack that was going on about 9:00 in the morning.

It was just 55 minutes since Miller had taken that final bearing by tuning in on the Honolulu radio station. The leaning column of smoke I had seen then was now close enough for us really to see its source.

There was so much smoke the sun was obscured and lemon-yellow gun flashes pierced the somber backdrop. Except for the fiercely burning Arizona, all the ships were letting go with everything they had — battleships, cruisers, destroyers, submarines, and little boats. The whole system of shore defenses was in action. From Fort Weaver, clear on the other side — where this couple with me had planned to spend a lazy day — the Army had angry guns shooting at the darkened sky. But where were all our planes, Navy and Army?

When we reached the southeast segment of the harbor, at the entrance of Hickam Field, I left the blue sedan and that admirable couple. I hope I thanked them adequately in my hurry. All over Hickam Field there were fires — answers to the questions in my mind about our planes. Rows of planes were blazing on the field. So were hangars, barracks, and other buildings. Guns were rattling and pounding around the field. Men were fighting fires.

Hitchhiking to War

I got another hop in a station wagon from a Filipino clad in sailor whites. Apparently he was a steward for some captain and had been sent ashore the day before to do some marketing. The floor of the station wagon was loaded with vegetables, and piled on top of them were about as many men as could squeeze in. All of us jumped out at Hospital Landing, except the driver, and joined a throng of a hundred or so soldiers, sailors, Marines, and civilian employees on the channel edge. What we saw then was so overwhelming that I felt as if something had me by the throat.

Thirty yards out in the channel, and seeming to tower over us, moved the vast gray bulk of an old-type battleship. She was traveling slowly, and on her deck, stretcher bearers were rushing to carry away the wounded, while steel was roaring skyward from her 5-inch antiaircraft weapons, her lesser cannon, and machine guns. Beyond her, at the far end of Battleship Row, lay the Arizona, the blackest sort of smoke belching from her broken, twisted wreckage amidships and forming fantastic, ominous shapes in the sky. One fighting top and tripod mast canted out of this incredible shambles. On all the ships in that double two-mile lane, guns were blasting at the planes. Yet all the terrific power of the biggest guns on those battleships was ineffective now. They were made to fight monsters like themselves, not a swarm of gadflies.

The ship near us was trying to get out to sea, and the Japs were trying to sink her in the channel, where her 29,000 tons of steel hull, machinery, and guns would choke Pearl Harbor and bottle up the fleet. There was a tremendous ear-splitting explosion. A bomb had struck on her deck close to one of her antiaircraft guns. Thirteen hundred men, I guess, were aboard the ship. Some were killed, more were hurt, but only one antiaircraft gun stopped firing. Everywhere I could see, the crew was well under control. For the first time in my life I was seeing a naval vessel in action, and I was just watching in that helplessness in which you find yourself caught sometimes in dreams. But this was real enough, and what was striking at the battleship was a newer weapon, my kind of weapon. Dive bombers.

All the time I was watching the attack I was trying to evaluate the ability of the Japanese as dive bombers. They had concentrated at least the equivalent of one of our own dive bomber squadrons in an effort to knock out the ship. Eighteen, possibly 20, planes took part, going at it one by one. They were so eager that bombs fell first on one side of the old battle wagon and then on the other. We on the landing had to throw ourselves flat before each explosion because the concussion was terrific. If caught standing, you would be knocked flat. Lying down on the concrete or on rocky earth, I had a frantic impulse to claw myself into the ground.

Dodging Death

The battleship got clear of the channel all right, and grounded on a point of land opposite the hospital. Just at that time I had turned about to watch the bombing attack on the destroyer Shaw, which was going on behind us. As I watched, a bomb tipped her bow, and after the explosion, fire broke out.

Just then a motor launch picked us all up and shuttled us across to Ford Island. A lot of damage had been done there. Three or four squadrons of PBYs, which are big patrol planes sometimes called Catalinas, had been massed on the point of the island. Only charred remains were left. I could scarcely believe what I was seeing. Hangars were afire, and their glass-wall fronts were black with holes. In front of the nearest hangar was the appalling wreckage of those Catalinas. There was nothing shipshape anywhere in sight. As we watched from the concrete ramp, there was a great flare across the channel, and a tremendous blast. The destroyer Shaw had blown up. Fire had reached her magazine. I saw a big ball of red fire erupt from her. It shot up like a rocket to about 400 or 500 feet. Spellbound, I saw it burst open from the middle. It was like a rotten orange exploding. The concussion knocked me on my face.

Someone yelled, “Here comes a Jap plane!” We swarmed into the undamaged hangar. Not one but a number of planes roared across Ford Island with their guns going. I was behind a steel column in that hangar.

In a few minutes I was on my way again, to the other side of the air field, where the carrier planes are based. The island is a little more than a mile long, and in places about three quarters of a mile wide. Right down its middle is a runway. Sprinting on that stretch of concrete, I saw that it was strewn with pieces of shrapnel, misshapen bullets from Jap machine guns, and empty cartridges that had fallen from their planes. I could guess, from the quantity of this stuff, that they had done a lot of systematic strafing here to keep our fliers on the ground. They love to strafe. It seems to be characteristic of them, a thing that has been noticed in many of the battle areas.

Marines at Ewa Field told me they saw a Jap gunner quit firing long enough to thumb his nose at them. Another Jap, while strafing the Marines, was moved to let go the handles of his gun, clasp his hands high above his head and shake them in that greeting with which American prize fighters salute their fans. Then he grabbed his guns and shot some more. This will help to explain why the United States Marines could hardly wait.

The Ties of Conflict

When I reached the other side of the air field, I could find only 3 of the 18 pilots with whom I had left the carrier about three hours before. Communications were pouring into the command center. I went to find out if the Japanese carriers had been located. My commanding officer, Lt. Cmdr. H.L. Hopping, was there. He had been able to get in with just a couple of bullet holes in his plane. Others of our squadron trickled in until we had about half our planes and pilots on the ground.

We were all so glad to see one another alive that it was a deeply touching scene. With a whoop of delight, I saw Earl Gallaher walk into the command center to report for instructions. Lieutenant Gallaher was the executive officer of Scouting Squadron 6. As flight officer, I was third in the squadron — that is, next to Gallaher, who was second in command. We shook hands in an effusive greeting and then just stood there for a few seconds, grinning at each other. There wasn’t time to say much. We were expecting to be sent after those Jap carriers as soon as they were located. So we went back to see what planes we could find, and managed to get together nine planes that we could man. We had bombs put on them and the rear guns manned.

Those of Scouting Squadron 6 who were present and accounted for finally decided to get a little sleep. We had our orders — to be up and standing by at 4:00 the next morning. We went to sleep on cots. The next thing I knew, it was 4 a.m., and I was dressing in the dark.

We got orders to take off immediately and fly out to the carrier. We didn’t think much of that idea. We thought considerably less of it as somewhere a gunner began shooting red-hot pin points into the overcast sky. He was directing his tracer bullets at the only point of light he could see overhead. Then it seemed as if every gun within a 10-mile radius was being fired. That lasted about 10 minutes, until, one by one, they discovered they were shooting at a star.

Commander Hopping was impatient to take off. Happily for us, it was daybreak by the time we started down the runway, and men on the destroyers down that way could see who was aloft. After flying in absolute radio silence some 80 miles to a rendezvous at sea, we found our carrier. She was out there with the task force, of course, and she was flying the biggest American flag that I had ever seen on a ship. It was her battle flag, flown only in battle. Seeing her out of sight of land, in fighting trim, we were more than ever grateful for the bad weather that had delayed our return from Wake.

Under normal conditions she would have been at her dock by 6:00 on Saturday night — and so would another carrier, the Lexington. On the maps of the harbor carried by the Japs, the data were so nearly up to the minute that the two carriers were shown where we ourselves had expected them to be — until that bad weather delayed us.

I have been attached to one ship or another for about a fourth of my life. Almost invariably, you develop a warm feeling for your ship, but for a carrier the feeling is deeper. When you fly as one of the air group of a carrier, no matter how confident you are of your ability as navigator, each time you actually find your carrier on an otherwise empty sea, your heart sings a little.

Everyone on the carrier was wild with curiosity, and the experiences of each of us were heard over and over, with flattering attention. We got a few scraps of information on what had happened to other members of our squadron. One had jumped a Jap fighter about the same time I was shot down and in the same area, near Barber’s Point. The Marines at Ewa Field had witnessed the action. Apparently, our man was doing a fine job and was getting the best of the Jap — a real test of his skill, because our scout bombers weren’t designed to outmaneuver fighters. He was so intent on keeping his fixed guns pouring bullets into the rear of his adversary that when the Jap pulled up the nose of his plane — possibly there was a dead pilot at the stick — and it lost forward speed, our man’s plane collided with it. Pilot and rear-seat man both jumped. But there wasn’t sufficient altitude, and their parachutes failed to open in time.

As we listened to stories like this one, a pattern of understanding soon formed, and we realized that revenge was going to be our job. We would have to get those Jap carriers somehow, somewhere, someday, and not waste time and hurt our personal efficiency by brooding over the deaths of our friends.

By Tuesday morning, after the task force had dropped into Pearl Harbor for oil and provisions, the hunt started again. The task force was in charge of Vice Admiral Halsey, who believes in action, and we knew we would do some real punching. We didn’t catch the carriers on this jaunt, but the area was infested with long-range Jap submarines and we potted plenty of them.

The Wednesday-morning scouting flight turned up several subs, and we were sent out to get them. I took off after one of them around noon, when our carrier was 200 miles north of Pearl Harbor. As my rear-seat man, I took along a lad named Merritt, who was about 21 years old. He turned out to be an extremely reliable radioman and gunner.

The sub had been 75 miles to the south when seen at 6 a.m., and naturally had had time to move elsewhere in the interim. I flew a big rectangle over the probable area. After about an hour I spotted her, lying on the surface, about 15 to 18 miles distant.

I headed for her, meanwhile radioing the carrier: “This is Sail Four. Have sighted submarine. Am attacking.”

I was about 800 feet off the water, and to make a good dive-bombing attack I would have to start from 5,000 to 6,000 feet, at least. So I began climbing, too, desperately hoping the sub wouldn’t submerge before I could unload. She didn’t, and as soon as I was within range, her deck guns began throwing shells at me.

“Is the bomb armed, Mr. Dickinson?” Merritt kept asking me. He was referring to the removal of the arming wires, which prepare the bomb to explode on contact. It is the pilot’s job to do this and the gunner’s job to remind him, lest the bomb fall a dud. This kid Merritt was getting his first chance for revenge and he was determined not to have a failure on his hands.

“Look here,” I finally said. “The bomb is armed. For God’s sake, relax. Maybe we can get this sub. Take my word for it, the bomb is armed.” At the same time, the carrier was calling me for a progress report. I replied that I would call in after dropping my bomb.

The Jap’s two deck guns fired at least 25 antiaircraft shells at me. I had had him in sight for almost eight minutes. Yet he had made no attempt to submerge. All he was doing was turning to the right a few degrees. Obviously, there was something wrong with him. Probably he was unable to submerge.

Now the Japs were firing a couple of machine guns too. The explosions from the antiaircraft guns occasionally washed a slight tremor into the plane.

I was getting nicely set when my gunner spoke again, “Is the bomb armed, Mr. Dickinson?” I dived.

All the way down I could see those heathens still shooting. When I was about 30 stories higher than the Empire State Building, I yanked the bomb-release handle. By the time I was able to pull out of the dive and turn so as to get my plane’s tail out of my line of vision, it was probably 15 seconds after the bomb struck. It dropped right beside the submarine, amidships. In about three quarters of a minute after my bomb struck, the sub had gone under.

Right after she disappeared, from her amidships, as near as I could tell, there was an eruption of oil and foamy water, like the bursting of a big bubble. Seconds later there was a second disturbance. Another bubblelike eruption of foam and oil churned to the whitecapped surface of the sea.

This time I saw some debris. I reported to the carrier what I had done and what I had seen. But I was careful to say that “possibly” the submarine had been sunk. You simply can’t be sure on such evidence.

“Looks like we got him, Mr. Dickinson,” chirped Merritt.

“Yes, I think we did.”

“That’s certainly pretty nice, huh?”

I said it sure was.

Attack on Kwajalein Atoll

We had one fairly uneventful cruise of 10 days, and then our carrier went out from Pearl Harbor again as part of a convoy escort. The convoy was carrying reinforcements to our garrison on a South Sea island base, which protected our supply line to Australia and had to be strong enough to withstand whatever the Japs might send from their islands. Except for those reinforcements, the Pacific route to Australia might have been cut, and men and supplies for any offensive would have to be brought clear around Africa.

We stood guard in the open sea while the reinforcements were being discharged, then departed. We got orders to be ready for action. Our task force had a real job to do.

On a day around the end of January, we altered our course and turned west toward the Marshall Islands, primed for an all-day attack. The Japs had called at Pearl Harbor on a Sunday eight weeks before. This was our first chance to return the call.

We got up early — about 3:00 in the morning. The anticipation of battle was a noticeable thing in the wardroom, something you could detect almost as plainly as you could smell the fragrance of the coffee, toast, and bacon. This middle-of-the-night breakfast was the climax of four or five days of tension, of worrying. Each man was challenging his own soul to tell him how he would measure up in battle. No man ever lived who got the answer in advance.

I was feeling a trifle smug because twice before I had been under fire. All of us who had been up at Pearl Harbor were exchanging glances; we were regarding one another with a certain comfort. We were, we felt, veterans.

I had put the first piece of fried egg in my mouth when I made a peculiar discovery: I couldn’t swallow. That piece of egg seemed to swell and turn into something the size of a tennis ball. I crammed my mouth with dry toast and washed it down with water. After puttering a bit with my knife and fork, I decided to call that piece of toast my breakfast and went to the ready room of Scouting Squadron 6.

We pilots took our places in 21 chairs arranged in seven rows of three. Time spent in the ready room is as much of a strain as flying. But after every scrap of data was down and digested, the seconds began to drag and minutes were like hours. Actually, of course, we hadn’t been there long. It still was night when finally we heard the telephone, and the talker relayed the order we’d been waiting for: “Pilots, man your planes!”

Scouting 6 had something like 175 miles to go to reach its objective, Roi Island, which is a part of Kwajalein Atoll. The scouts were going to attack; the bombers were coming along in reserve and to see how we made out. Then they were to seek an objective. Whoever came back from this raid, we knew, would be able to draw a better map of Kwajalein Atoll than the one we carried with us. Well, we would bomb whatever we could see.

After 30 or 40 miles, below we could see many islands. These were low-lying, circular reefs, and down there, 10,000 feet below, were many Japs, and we hoped the Japs were sleeping.

We had been told to make a glide bombing attack. In a dive attack you swoop down at the target at an angle of 65 to 75 degrees, but in a glide attack, you approach at an angle of no more than 55 degrees. Our skipper, Lt. Cmdr. Hopping, had labored mightily to get us ready for this morning’s work. Hopping was a brilliant tactician. He taught us a lot, and our squadron went into the war much better off for having been his. A graduate of the Naval Academy, class of ’24, he was a tall man — 6 foot 1 — and strong, and strong in his opinions too. But he was extremely hard to “fly on.” Men don’t fly with equal skill any more than they play tennis with equal skill. We were always a little leery when flying on Hopping, but we were devoted to him, and therefore afraid that he would get himself into a situation out of which he couldn’t fly.

We had climbed to 15,000 or 16,000 by the time we reached Roi Island. After about 15 minutes, far off to my right I saw my skipper starting to coast, taking the first division in. I saw their bombs exploding on the ground, saw fires erupt down there, and knew the skipper’s division was strafing hangars and field. But what I did not learn until later was that a Jap fighter was taking off from the airfield as our skipper was coming down at the head of his division.

Earl Gallaher, leading the second division, saw it happen. Seemingly, Hopping had pushed over too early. You really ought to have that angle of about 55 degrees as you come down on the target to give you the speed you need. And you do need it. A shallow angle won’t give you that extra push. We know that well now. As the skipper reached a low altitude he was still some distance from the island.

Instead of going in at 300 knots, or, better still, 350, he was doing no more than he could get with his engine, which was scarcely half what he needed. Passing over the island he was a low, clear target, and they concentrated on him. A Jap fighter, just getting airborne, came up on his tail. The skipper’s plane struck the water and went right under. Gallaher, diving, saw the whole thing plainly.

I took the third division in on the left of Gallaher’s. We made practically a simultaneous attack. I think our 12 planes arrived at the end of our glide with considerably more speed than those first six planes had had. Going in, I saw the angry flashing of the antiaircraft guns throwing stuff at us. But it is surprising how quickly you come to a state of mind which almost disregards AA fire. It doesn’t bother a pilot much more than lightning. It isn’t especially effective — yet — but more important to your self-control, as your enemy trains his big guns on you, is your utter absorption in the job you are doing. A man who has precious bombs to drop hasn’t time to be scared.

I had three, but I was saving my 500-pounder for dessert. What I released as I flew toward a bunch of buildings on the airfield were my two 100-pounders. After pulling out, I kicked my tail around, the better to see what damage I had wrought. My two bombs hit a building or a house.

My wing man, Lt. Norman West, who was flying just back of me, had startling luck. His load struck right next to the building I hit, but he got the jackpot. It must have been a storehouse for ammunition, probably TNT. It went up with a tremendous bang and a gigantic flare. An enormous smoke cloud came swelling after us. When that smoke thinned, there were no buildings left there. They had been leveled. That was quite gratifying.

Crossing the island, we scattered. I found myself well off the island, about 1,500 feet above the sea, completely entranced with one of the most glorious fireworks shows I had ever seen. The moon was gone and the first glowing hint of morning was in the east. All over the island there was an extravagant flowering of flame. Great white-and-pinkish-streaked fire shapes bloomed profusely, each for just an instant, as plane after plane went in and unloaded. The explosions were fiercely jagged, intensely bright. The Japs down below were getting more than a taste of Pearl Harbor.

I must have been a mile off the island, above the sea, just drunk with the fantastic beauty of this extraordinary dawn before I suddenly realized that for any antiaircraft gunner on the ground or any Jap fighter in the air I was just a cold turkey. Several thousand feet up I saw a couple of our planes. I pulled up the nose of my plane, shoved the throttle all the way forward, and went away from there, sensible again. As I breezed up alongside my friends and they fell in on either side of me, we all felt better.

We three had come together for mutual protection just in time. On my left-hand side, two Jap fighters — the first I had seen — were coming in to make an attack on us. They took turns making runs, but always both from the left. Had they known a little more about their business we would have been finished, because for some reason our rear-seat men were having a bit of trouble with their guns just then.

I had time to wonder what species of shark would get me for his breakfast when our rear guns got going and started shooting dark red lines at the Japs. They turned tail and ran. Apparently these two had never affiliated themselves with any suicide squadron.

Watching them climb up and away, I gave a sigh of relief that practically blew the cockpit open. Then they really did astonish us. Out of range, the two of them started doing stunts. They looped together and followed with an elegant slow roll. This went on and on. They just sat up there, well out of battle, and did what we call “flat-hatting,” a term for all kinds of stupid, show-off flying. They had been sent to fight us, but they just kept on waltzing in the sky. I can’t guess what was in their minds, unless they had agreed they weren’t going to risk their necks excessively for dear old Nippon.

I had just rendezvoused with two others of my squadron when a report came over the radio giving information we had been yearning to hear.

“Targets suitable for heavy bombs. Targets suitable for heavy bombs at Kwajalein anchorage.”

I recognized the voice and was satisfied that this was no wild goose chase. The voice had come from somewhere in the sky above. It was that of Commander Young, our group leader. We three immediately headed south.

Kwajalein anchorage was 40 miles or so from where we were, and everybody wanted to get there first. Targets for heavy bombs were what we all had been hoping for, and when mention of a carrier was added to the good news, that was like offering fresh meat to dogs.

Because we had to climb, we could do scarcely more than 130 miles an hour. I was leading my three-plane section. The pilot on my right, a big fellow, kept shoving his shoulders and arms forward in a pantomimed plea to me for hurry. That was Dobby — Ensign Dobson.

Lieutenant Junior Grade Kleiss was the other pilot. He has had a nickname ever since a day when he landed at the Hawaiian Marine base, Ewa Field, before it was fully paved. Kleiss had turned his tail up into the wind and his propeller was blowing up a lot of dust, which hid the plane from the man in the control tower. So, when Kleiss called, requesting permission to take off, by radio the reply came back: “Unknown dust cloud. From Ewa Field tower. Permission granted.” So he had become Dusty.

In no more than seven or eight minutes, we could see a vast ruffle of beach sand embroidered with lacy surf and touched here and there with green. Inside this ruffle was the lagoon, Kwajalein anchorage. Moored there in five or six symmetrical rows, as if on a chart, were more than a score of ships.

I saw one new cruiser, a row or two of big auxiliaries, an old light cruiser, tankers, a seaplane tender, three or four submarines and other ships. As we flew over the reef toward all these fine targets, I saw on the beach below us two great four-engined flying boats. They were temptingly exposed to strafing, but we had no time for that. All the ships were shooting at us as the wide atoll beach passed astern of our three planes.

It was broad daylight then, nearly 20 minutes to eight. Far below on the wide lagoon, the big new cruiser was winking at us with many glittering eyes. Time and time again as her 8 or 10 bigger antiaircraft guns let go, she seemed to be an angry mass of living flame. All told, that one warship probably had 30 or 35 guns shooting at us.

We had gone far apart to make the attack. I was on the left, Dobby in the middle, and Dusty on the right as we put our noses down and went into steep dives.

I was sighting at the deck of a tanker, of 12,000 tons I’d say, when I saw that all the while she’d been masking a richer prize. It was a thundering big Jap liner. She was about 17,000 tons. Poised aft, high up on her stern, was a seaplane. I wanted this liner. I pulled my nose up to hedge-hop the tanker and aimed right for the plane on the liner’s deck; aimed well, too, because my 500-pound bomb struck the stern, and the blast of it wrapped her in flame.

As I pulled out of my dive at 600 feet, the Jap liner was well on fire. I saw Dusty’s bomb land right on the big new cruiser, and a lot of Japs aboard her stopped shooting. Dobby’s bomb struck a submarine tied alongside a bigger ship, the tender. The sub blew up and sank so fast that the tender listed from the pull of lines and gangways.

Because of my passionate interest in what was going on, any concern for myself was simply crowded out of consciousness. It was as if somebody else were flying and I were watching. My best subject at the academy had been naval battles; I had such an interest in old sea fights that I would sometimes argue in the classroom with instructors and get my ears knocked down for stubbornly coming back lugging 11 books to support a point. Right there at Kwajalein anchorage, below, above, and all around me was a sea fight, and it wasn’t in any book.

War from a Box Seat

I’ll admit that if I find myself alone in a dark, creaky old house, I can scare myself near to death. But neither at Pearl Harbor nor afterward in action was I really scared. There is worry underneath, of course, and the nervous strain of it finally tells in subtle ways.

But battle is grand excitement. It is excitement beside which any other kind I’ve ever known seems diluted and lacking in the real flavor. This was the essence.

I hung around watching the show until the antiaircraft shells burst too close, then got out of Kwajalein. I was about 40 miles out over the water when Dobby and Dusty caught up with me. The three of us headed back to the carrier.

I was standing on the deck as our carrier was warped in to Pearl Harbor. I heard her cheered as she came around the island. The commander in chief of the Pacific, Admiral Nimitz, had passed the word around about our raid on the Marshalls. Work would stop on any warship the carrier passed, and men would crowd to the rail, even on the half-submerged wreckage of the Arizona. In impudent Tokyo broadcasts, the Japs had been asking the world, “Where’s the American Navy?” Well, now they knew where a part of it had been.

That was why there was something special in the cheers our admiral got, and hearing them was something special for any Navy man. We could see the admiral’s head and shoulders as he walked back and forth on his bridge high in the superstructure. Several times he raised his hand to salute friends greeting him from the dock. Afterward, we heard the admiral had tears in his eyes. I shouldn’t wonder if he had.

Footnote: Lt. Dickinson engaged in numerous additional air battles, sank another Japanese ship, ditched a plane in the ocean after running out of fuel, and must be regarded, by any account, as one of the great heroes of the war.

American Life after Pearl Harbor

To help us mark the upcoming 75th anniversary of the attack on Pearl Harbor, we asked you to share your memories and family stories of how life changed after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor. Here are the stories some of our readers have shared.

Do you have a memory or a family story you’d like to share about life after December 7, 1941? We’d love to hear it! Click here to find out how.

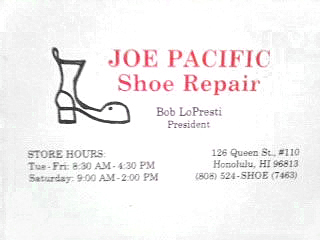

An Italian Cobbler in Hawaii

From Joe Pacific Jr.

On December 7, 1941, my dad, Joe Pacific Sr., was having breakfast in his house in Honolulu with my eleven-year-old half-sister when they heard the distant explosions. He had a house on his property that he rented out to an Army officer. On that December 7 morning, my dad went to the door of the rental house, knocked on it, and woke up the officer, saying, “Get up, you have a war to fight!”

Later that day, the government agents were at the door saying that they had to take my dad to the immigration station to “check his papers.” My dad had emigrated from Italy as a teenager. He learned how to repair shoes in the United States and worked as a shoe repair shop manager in New York City until the shop closed during the Great Depression in the early ’30s. Then he moved to Hawaii after seeing pictures of paradise in the theater. In Honolulu, he opened a shoe repair shop, Joe Pacific Shoe Repair, that is still in business with a new owner who kept the shop’s original name.

The government agents did more than just check my dad’s papers. During the war in Hawaii, citizens of German and Italian ancestry were rounded up and detained alongside the Japanese. They held him for three months, eventually moving him and other Italian, German, and Japanese detainees to a hastily constructed tent camp called Sand Island in the harbor of Honolulu. In fact, the first Japanese prisoner of war was held at the Sand Island Detention Center. The prisoner was a crewman from a midget sub that had been damaged on the day of the attack. My dad said that this POW kept burning his arms with cigarettes to try to kill himself, as it was a dishonor to be captured alive.

The Japs Were Poor Shots

From Barbara Holyoak

My uncle, Robert Morrison, was in the U.S. Navy and was stationed at Pearl Harbor. He was assigned to serve in the Navy postal department and was driving a postal truck at the time of the bombing. He picked up many of the wounded and transported them to safety. During the rescue mission, planes would swoop down on them, machine guns peppering bullets, forcing them to dash for shelter under the truck. He risked his life many times, but continued his mission to pick up and help the wounded to safety.

He said the Japs were poor shots. He was lucky.

Mistaken Identity

From Mildred Bailey

I am from Oahu, Honolulu and my daddy was in the Navy stationed at Pearl Harbor. We were taking him to his ship and just when we got to his gate to let him off, a Japanese plane flew over our heads — we were being attacked!

I was 5 years old and saw the big red sun on the plane wing.

Someone in the military police carried me under his arm, and the rest of my family ran to his jeep. We were rushed to a bomb shelter while bombs were dropping on the ships. I could see all the planes, fires, and damage starting.

We stayed in the bomb shelter for a long time and had to wear gas masks. When the all-clear signal blew, we left the shelter to see the damage and fires.

My daddy was safe!

When we got home, the military police were going from house to house rounding up the Japanese neighbors, where I was visiting my 5-year-old friend. The military police man asked my friend’s mother if I was her daughter, and since I wore a Japanese haircut, she said yes and I was taken with my friend and his family to a Japanese camp with barbed wire all around, into a camp house made like those the Germans used.

My family couldn’t find me when I didn’t return from my classmate’s home. They were told I was taken with the family to a camp during the Japanese round-up. My grandmother, aunt, and brothers had to get my birth record to prove that I was not Japanese.

I have not forgotten what I saw at Pearl Harbor. I am 80 years old now and the memories are still fresh today. I’m thankful that my family — my dad, uncles, and brothers — all survived.

Ragged Old Flag

From W. Neigh Gallagher

He fought on the beaches of Normandy and in the Battle of the Bulge to secure freedom for millions. His D-Day came on Saturday, October 8, 2016, when WWII vet Leon Wiseman died.

The men and women of the “Greatest Generation” are dying at 1,000 men and women a day. All are in their 90s and 100s now. Words like duty, honor, reverence, patriotism, loyalty, godliness, fidelity, and trustworthiness marked their lives.

Even in his later years, when blind, Leon recited to audiences (from heart) the words to Johnny Cash’s “Ragged Old Flag,” precious words memorializing the values he held dear.

Dad Got Serious

From Bright K. Newhouse Jr.

I was born in Fisher County, Texas, on April 11, 1931. On December 7, 1941, we were getting ready to go to church. We were listening to our radio on battery when the news came over the air waves: Pearl Harbor had been attacked by the Japanese. My dad got serious, and I knew it was important.

I will always remember that time for the rest of my life.

News in the Midwest

From Ellen Loken

On the first Sunday in December, my parents, sister, and I had finished eating supper, but remained at the table to listen to The Jack Benny Show. Halfway through the program, an announcer broke in to say that Pearl Harbor had been attacked.

My parents looked at each other. They had lived through World War I. Jean, 7, and I, 9, didn’t really understand at the time. On December 8, President Roosevelt declared war on Japan.

My dad became an air raid warden, though chances of enemy planes reaching north Minneapolis were nil.

Years later, while working and living in San Francisco, I became lifelong friends with a Japanese girl. She told me her family members had been truck farmers in Lodi, California; they were sent to a detention camp, and she had been born there.

A Neighbor Lost

From Nancy Lockwood

My mom, dad, younger brother, and I lived in Bedford, Ohio. I was 8 years old. It was a Sunday. I had been at church that morning. The big Philco radio in the living room relayed the message of the terrible bombing raid at Pearl Harbor.

The Leeks family lived next door. They had two older daughters, a son, Herbie, who was in the Navy, and a much younger daughter — 7-year-old Sally, who I played with. Herbie was stationed in Hawaii, and his parents spent a frantic day trying to find out if he was okay.

Monday was a school day, as was Tuesday when I walked home and saw a black car parked in front of the Leeks’ home. Two military men walked back to the car, and Sally ran out to tell me her brother had been killed on December 8 while he was helping repair the electric power in Honolulu.

My dad had been a member of the Ohio National Guard for most of my life. He had not been shipped to China the year before with most of the men in his unit because he had two children. They had been sent to help Chinese soldiers learn how to use American weapons as they resisted the Japanese army invading their country.

When December 7 happened, those guardsmen remaining became the home guard. For the duration of World War II, my dad monitored his assigned area of our town during blackout air raid drills. Every home quickly found ways to cover all the windows so no light could be seen by any potential bomber flying over the city, and lights inside were turned off. A flashlight or maybe a candle in a dark room was all we had to see by until the all-clear siren sounded.

Fear of being bombed, probably by German bombs, was constant. We played and went to school, but there was a sort of alert tension all the time. Few folks believed we could be reached by bombs so far from the Atlantic coast, but we were vigilant. After all, London had been bombed by V-2 bombers all the way from Germany. And the Cleveland area was where steel and tanks and planes were being made (and probably more stuff I didn’t know about).

Protecting Freedom Is a Family Business

From Mark Kintzley

Shortly before the Pearl Harbor attack on December 7, 1941, two of my mother’s five brothers (Bob and Louis Byron) had joined the Navy. They were both assigned to the repair ship USS Vestal.

My Uncle Louis narrated the attack on Pearl Harbor to one of his sons, who recorded the narration. At the time, Louis was long retired and in the late stages of Parkinson’s disease.

The USS Vestal was moored to the USS Arizona on Saturday, December 6, so that the crew could have an early start repairing it the following Monday. But that was not to happen as the Japanese attacked Oahu on Sunday, December 7.

After devastating the U.S. airplanes on the airfield, the Japanese attacked the ships in Pearl Harbor. The Arizona received the first bomb hit at shortly after 8 a.m. The bomb went through four decks and hit the munitions storage, which split the ship apart. It took only nine minutes to sink.

The blast from the Arizona sent the captain and many sailors flying into the waters. “Abandon ship!” was thought to have been announced. The Byron brothers had not heard such a command, so they remained aboard as the captain boarded and ordered those swimming toward shore to return to the Vestal.

The Vestal itself was bombed and strafed as the captain moored it to Aiea and repaired it quickly and then proceeded to assist other ships in need. The captain and crew saved other sailors and Marines who were thrown into the water. Captain Cassin Young would receive the Medal of Honor for his intense efforts and bravery. He would later die in service of his country.

My uncles helped pull many Marines and sailors from the oily and fiery fields. As far as I know, neither received awards for their heroism during the attack. Both were very hesitant to talk about their experiences at length until Louis relented to his son.

All five of my mother’s brothers served in the military — three in the Navy and two in the Army. As a 3-year-old in 1945, I recall my two uncles coming through the front door of our house in Fort Collins, Colorado. My parents commented that the hype was extraordinary during the times, and it was no different in our household as our heroes were streaming homeward throughout the country at the end of the war.

In my family of 14 siblings, six have served our country — two in the Army and three as Marine Corps. Many of our children have served (some in the Gulf War) or are now serving in the military, including every branch.

Saving Mops

From John Volpe

In March 1999, Newsweek ran a special issue about Americans at War, and part of it covered Pearl Harbor, for obvious reasons.

In that story was the story of Adam Czerwenka, who was stationed on the West Virginia. My uncle, Tony “Mops” Volpe, was on the West Virginia and had always thrilled the family with the story and how the events unfolded that morning. So I read with much interest the story of Mr. Czerwenka.

He had found a motorized launch and thrown it into the harbor to boat around and pick up men who had abandoned ship. This was a big part of uncle Tony’s story, and I was excited!

Tony had told us many times that he and many others had been sleeping when the bombing started. He had run up on deck with many others to see the inferno that was the Arizona, and the West Virginia was hit. They had to abandon ship. They jumped in the water and the water was COLD, he told us, which was hard to believe since it was in Hawaii.

Tony was not a good swimmer, but as fate would have it, some sailor came around in a motorized launch and pulled him and some others from the harbor. He saved Tony’s life!

For over a week, no one in the family knew if Tony had survived, due to the minimal communication with Hawaii at the time. It was a tense time, Dad would always tell us.

Anyway, I wrote to Newsweek to tell them this story and to ask that they pass along a BIG THANK YOU to Mr. Czerwenka. They did better than that … they helped me get in touch with him via email.

We had several email communications, but Mr. Czerwenka was in failing health. He had tried to find his roster book from the WEE VEE, as he called it, to locate Tony Volpe, but I did not hear back from him from my last email. I only thank God that he was at Pearl Harbor helping save Americans, and PROBABLY my uncle.

My uncle had passed away from a virus in 1995 that, oddly enough, he had picked up on a return trip to Pearl Harbor. But we still reminisce about his stories. And we have a postcard that he sent to my dad in December 1938 telling dad that he had been assigned to the West Virginia and was leaving Great Lakes Naval Base for San Diego right away.

The Last Ring Home

From Minter Dial II

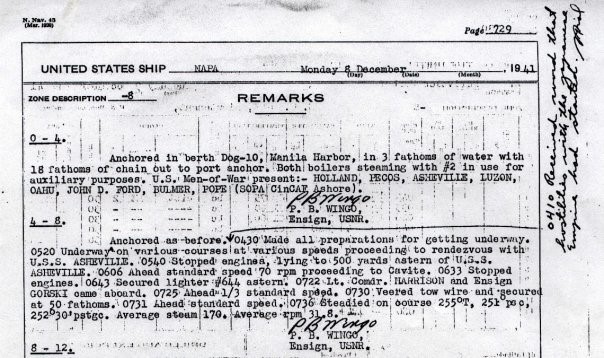

My grandfather, Lt. Minter Dial (USN), was stationed in the Philippines in December 1941. In the early morning of December 8th, across the dateline, at 0410 hours, as captain of the USS Napa, he handwrote in the logbook the following words:

“Received word that hostilities with the Japanese Empire had started. M Dial”

The USS Napa was scuttled in March 1942 (the logbook was saved and is now stored at the National Archives). My grandfather was awarded the Navy Cross for bravery before the fall of Bataan and Corregidor, but was then taken prisoner by the Japanese for the following 2 1/2 years. He was killed in January 1945 after American dive-bombers hit the unmarked Enoura Maru hellship.