Eugene Field Helped Craft America’s Sense of Humor, Then We Forgot Him

When Eugene Field died in 1895 at age 45, fellow authors and friends hastened to share their fond memories of the humorist and poet. He was a hilarious prankster and a heavy drinker with an impressive book collection, but, most of all, he was a loyal friend.

Field was born 170 years ago on September 2, 1850, although he reportedly told people his birthday was September 3rd if they were late to wish him a happy birthday, just so they wouldn’t feel too bad about it.

Even though more than 30 elementary schools around the country have been named after the prolific writer, his literary renown has scarcely held up to the household-name status he enjoyed during his life. As a poet, he crafted the most popular children’s poems and lullabies of the era, including “Little Boy Blue,” “Wynken, Blynken, and Nod,” and “The Sugar-Plum Tree,” all of which were published in this magazine or its affiliated children’s magazines. As a newspaperman, Field garnered a national following for his witty columns documenting people and the arts, first in Missouri, then in Denver, and finally at the Chicago Daily News.

His column “Sharps and Flats” ran in the latter paper six days a week for the last 12 years of his life. By at least one account, he was the most popular columnist in the country during that time. Of a young Rudyard Kipling, Field wrote that “he has been flattered to an amazing degree since he woke up one morning and found himself famous” and that “there may be … twenty newspaper reporters in New York City capable of doing as good work as Mr. Kipling has done; at the same time, they have not done it and Mr. Kipling has.” Field gushed over a World’s Fair exhibit on Hans Christian Andersen, writing of “that dear heart which beat in unison with the simplicity, the truth, the candor, the enthusiasm, the wisdom, and the pathos of childhood!”

Field was also known for his scathing and sardonic quips on politicians of the day. In 1883, he wrote, “Grover Cleveland seems to have suddenly and completely dropped out of sight. Perhaps he is rehearsing Santa Claus for a Sunday-school celebration next Christmas. These politicians are queer people.” Writing for the Denver Tribune, he offered whimsical advice for all children aspiring to go into politics: “If you neglect your education and learn to chew plug tobacco, maybe you will be a statesman some time. Some statesmen go to Congress and some go to jail. But it is the same thing, after all.” One can imagine that Field would have found no shortage of bon mots to pen on the Progressive Era of American politics, had he lived to see it.

A few years after his death, Francis Wilson memorialized the writer in a biography published in this magazine as “The Eugene Field I Knew,” writing, “Field’s mind and heart were wide open to the sunshine of humor and the joy of laughter.” Sometimes this candidness expressed itself in wild antics, as when Field reportedly pranked a posh Thanksgiving dinner party by exploding the turkey with a firecracker: “He wasn’t invited back.”

Field’s close friend George H. Yenowine wrote for the Post several years later on “The Serious Side of Eugene Field,” claiming he had received the former’s last written letter. Yenowine noted that Field wrote his correspondence in six different colors of ink, depending on the tone of a given letter. He was also known to spend hours embellishing the margins with drawings and designs. In his letter to Yenowine two days before his death, Field went on excitedly about many projects he was looking forward to, before finishing the missive with a characteristic confession: “Irving Way has been wanting me to do the preface to the volume of Anne Bradstreet’s poems which the Duodecimo will publish; but Anne is a tough, uncongenial old bird, and I hesitate to tackle her. I suppose that one is justified in putting off a task he feels he cannot do well.”

Although Field’s prominence in the American literary canon has waned, his influential effect on humorists into the 20th century, such as John T. McCutcheon, Mark Twain, and even — tangentially — Molly Ivins, is undeniable. Don Marquis professed that he read “Sharps and Flats” every day. In his 2001 biography, Eugene Field and His Age, author Lewis O. Saum claims that Field created the newspaper column, and yet much of the writer’s work from the Chicago Daily News was lost forever: “We knew him very well for something like a half-century. Then, recalling little other than something labeled ‘calamitously sentimental,’ we averted our gaze.”

Field’s irreverent approach to constructing the record of the day can be remembered as a quaint, but formative, addition to the uniquely American voice; the oversized role he played in holding a mirror to the country and its politics at such a precarious time as the late 19th century has received a fraction of the attention it deserves.

Featured image: Buffalo Evening News, December 3, 1895

The Woman Who Cleaned Up America’s Dirty Work

In 1906, the prominent psychologist James McKeen Cattell published the first American Men of Science: A Biographical Directory. The 364-page publication strove to be “a fairly complete survey of the scientific activity of a country at a given period” by listing more than 4,000 men who’d contributed to “natural and exact sciences.” But the names listed in his directory aren’t all men. There are a handful of women in the book, and among them is Alice Hamilton. Today is the 150th anniversary of her birth.

Hamilton is included because of her work with “pathology and embryology of the nervous system; development of elastic tissue; tumors; tuberculous ulcers of stomach” and other specific medical research, but that only tells part of her story. As a researcher, activist, and humanitarian, Hamilton championed safer conditions in industrial workplaces and became the most important American advocate of what is known as occupational medicine.

Hamilton earned her medical degree from the University of Michigan in 1893 and furthered her studies in Minneapolis, Boston, Munich, and, finally, Johns Hopkins Medical School in Baltimore. In 1897, she began teaching pathology at Northwestern University’s Women’s Medical School in Chicago.

While in Chicago, Hamilton took residence at the famous Hull House, Jane Addams’ settlement house that welcomed immigrants, particularly women and children. She joined Addams as well as other social reformers like Florence Kelley, Julia Lathrop, and Alzina Stevens. Hamilton ran the house’s “well-baby clinic,” but she noted in her autobiography that conversations and camaraderie with the other women of the house shaped her work for the rest of her life. The women of Hull House were influential in promoting a minimum wage, fighting against child labor, and demanding social welfare at the turn of the century. Another important characteristic of Hamilton’s time at the house was her proximity to the working class of Chicago, where she began to help people beyond the confines of her distinguished medical training. She wrote of the changes she underwent during her 22-year stint at the Hull House:

“Life in a settlement does several things to you. Among others, it teaches you that education and culture have little to do with real wisdom, the wisdom that comes from life experience. You can never, thereafter, hear people speak of the ‘masses,’ the ‘ignorant voters,’ without feeling that if it were put up to you whether you would trust the fate of the country to ‘the classes’ or to ‘the masses,’ you would decide for the latter.”

Around 1910, Hamilton began to research the possibility of “industrial disease” in the U.S. While worksite accidents received some attention, she believed the dangers of various chemicals used in American plants and factories were going seriously underreported. Hamilton saw that European medical journals were brimming with research about industrial poisoning, while the U.S. had nothing to say about chemical dangers for workers.

From 1911-1920, Hamilton worked as a special investigator for the Bureau of Labor Statistics. She traveled from factory to factory, interviewing owners and managers in a sweeping, but informal, survey. Although she had little authority to assert herself, Hamilton credited American manufacturers for their openness in giving her tours. It wasn’t sufficient, however. She decided that, to get a more complete picture of the problems caused by white lead and lead oxide, she needed to go straight to the workers. Hamilton tracked down hospital records, interviewed workers who could scarcely speak English, and connected the dots of their health problems to lay the groundwork for sweeping reforms.

She went on to conduct similar studies for various arms of the government around the country, proving the risks involved with carbon monoxide, phosphorus, benzene, and many other chemicals used in myriad industries. Although she thought highly of many individual American industrialists, Hamilton maintained a deep distrust of the businessmen’s ability to self-regulate: “Perhaps it is our instinctive American lawlessness that prompts us to oppose all legal control, even when we are willing to do of our own accord what the law requires. But I believe it is more the survival in American industry of the feudalistic spirit, for democracy has never yet really penetrated into many of our greatest industries.”

In 1919, Hamilton was appointed as the first female professor at Harvard University, causing headlines around the country. She admitted that her breakthrough was long overdue, but, throughout her career, Hamilton expressed a belief that her gender helped her cause instead of hindering it. In speaking with factory managers and doctors, she said it likely seemed sensible that a woman would care for the welfare of workers: “It seemed natural and right that a woman should put the care of the producing workman ahead of the value of the thing he was producing; in a man it would have been sentimentality or radicalism.”

As a scientist, social welfare advocate, and pacifist, Hamilton remained active for the rest of her life. She lived to be 101 years old. Three months after her death, in 1970, the Occupational Safety and Health Act was passed in the U.S. The next year, the journal American Men of Science was changed to American Men and Women of Science.

Sources:

https://www.sciencehistory.org/historical-profile/alice-hamilton

Exploring the Dangerous Trades: The Autobiography of Alice Hamilton, M.D. by Alice Hamilton, 1942

Image Credit: Library of Congress

News of the Week: More Snow, Cloned Dogs, and the Wild, Exciting World of Celery

Winter’s Not Done Yet

I just looked out my window and it’s a wet, gray, early March day. I didn’t mean for that to rhyme; I just wanted to describe what it looks like outside my window.

I’m actually now in “spring mode,” ready to wear lighter clothing and put the shovels away, but winter isn’t finished with us quite yet. We just had a nor’easter that gave us a ton of rain and winds and damage to coastal homes, and tonight and tomorrow we’re supposed to get hit with another storm. This time more snow will be involved, anywhere between 1 and 12 inches, depending on where you live.

This is what I find funny about weather forecasts now: they have so much information that, in a way, they’re less accurate. A typical snowstorm forecast will go something like this:

“The European computer model says we’re going to get hammered by this storm, with over a foot of snow. The American model says we’re going to get only an inch or two. Then this third model says that we’re going to be somewhere in the middle, maybe four to six inches. We’re still collecting data, but that’s our best guess right now. Back to you, Ed.”

That’s a great forecast. I could have told you the same thing sitting on my couch in my sweatpants. But they used the word computer and showed a lot of Doppler radar images, so I guess we better pay attention to it.

People … People Who Need Cloned Dogs

I love dogs more than I love some people I know, but I’m not sure I could ever do this. Barbra Streisand cloned her dog. She wrote about it for The New York Times.

Streisand had her dog Samantha for 14 years, and just before the dog died, the vet scraped the inside of her cheek to get her DNA. The singer has a friend who did the same thing with his dog, and she wanted to try it to see if it would work. And it certainly did. It produced five puppies, three of which she kept and two she gave away.

It’s a little too sci-fi for me. I have this vision of an army of cloned little dogs taking over the planet. But I’m happy that Streisand is happy.

By the way, for the title of this section, I almost went with “Send in the Clones.”

Chiweenie

Every year I like to point out new words that are added to the various print and online dictionaries, even if sometimes they aren’t words at all. The Merriam-Webster Dictionary is my favorite. I just bought a brand new one because my old one vanished somehow, and it’s perfect timing, because this past week they announced some words that were added to the classic tome. And when I say “some” words, I mean 850.

Some of the new words and phrases include wordie (a lover of words), chiweenie (a cross between a Chihuahua and a dachshund, even if they’re not cloned), hate-watch (where you watch a movie or TV show even though you know it’s bad), and dumpster fire (which is defined as “a disastrous event,” though I’ve seen it used to mean a series of disastrous events, or just an overall definition of how things are going).

They’re also now including mansplain, but to be honest, I’m a little afraid to tell you what that is.

Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood at 50

To celebrate the 50th anniversary of Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood, PBS is airing a special this week titled It’s You I Like. It focuses on what Fred Rogers and the show meant to various people, including John Lithgow, Whoopi Goldberg, and Yo-Yo Ma. It’s hosted by Michael Keaton, who got his start in pictures as a crew member on the show. Here’s a preview:

The Razzies

Everyone knew who was going to win the Best This and That at the Oscars this year — the results were fairly predictable — but who won the awards for the Worst of the Year? The Golden Raspberry Awards, or Razzies, are held the day before the Oscars every year, and this year’s list of “winners” includes Tom Cruise for Worst Actor (The Mummy) and Tyler Perry for Worst Actress (Boo 2! A Madea Halloween), and The Emoji Movie was named The Worst Movie of the Year. Other people who won Razzies include Mel Gibson and Kim Basinger.

Oddly, the winners didn’t show up to accept their awards.

RIP Roger Bannister and David Ogden Stiers

Roger Bannister was the first person to break the four-minute mile, which he did on May 6, 1954. He later had a career as a neurologist. He died Saturday at the age of 88.

David Ogden Stiers was an actor best known for his role as Major Charles Emerson Winchester on M*A*S*H and for voice work in many animated films. He died Saturday at the age of 75.

Quote of the Week

“Now there are so many young people, and all my old friends are dead. They have either drunk themselves to death or they have naturally popped off the vine.”

—actor Christopher Plummer, on how the Oscars have changed

The Best and the Worst

Best: I’m cheating a little because this isn’t from this week, but I didn’t see it until this week, so it still counts, right? It’s a letter that New Yorker writer Alexander Woollcott sent to Ira Gershwin, and is now posted at Argosy Books in New York City. My favorite part is where he manages to tell Gershwin that he hopes he fries in hell, but still signs it “affectionately.”

Letter from Alexander Woollcott to Ira Gershwin, on display outside the Argosy Bookstore, New York. pic.twitter.com/wmtC2LGeP9

— southpaw (@nycsouthpaw) February 20, 2018

Worst: Just one last thing about the Oscars. Every year they have an “In Memoriam” segment, aka the “What People Are They Going to Leave Out This Year?” segment. Sure, it’s hard to pare down hundreds of people into a few dozen, but they’re making a decision about who to include and who not to include. This year they left out John Mahoney, Tobe Hooper, Powers Boothe, Dorothy Malone (who actually won an Oscar!), Adam West, John Gavin, Dina Merrill, Michael Parks, Jean Porter, Richard Anderson, Anne Jeffreys, and Michael Nyqvist, among many others — but they included people like a hairstylist and a public relations guy. I’m sure they were lovely people, but don’t tell me you don’t have time to include Rose Marie, a woman who was in the movies and television for 90 years, if you are going to include people movie fans have never heard of before.

This Week in History

Alexander Graham Bell Born (March 3, 1847)

The man who invented the telephone in 1876 would often greet people with a “Whoo-hoo!” when talking to them on the phone. Today, he’d probably just text an emoji. Here’s a Post piece from 1900 on how to use the telephone, and here’s Ron Carlson’s essay on why he wants the landline to stick around forever.

Barbie Introduced (March 9, 1959)

Next year will mark the 60th anniversary of everyone’s favorite doll. This month, Mattel is releasing new dolls to honor Amelia Earhart, Frida Kahlo, and other inspiring women.

This Week in Saturday Evening Post History: Freedom from Want (March 6, 1943)

The Post asked four writers to craft essays to accompany Norman Rockwell’s Four Freedoms paintings. Poet Carlos Bulosan contributed the essay for Freedom from Want.

The painting has to be one of the most parodied in history, with everyone from The Simpsons, superheroes, and the cast of Modern Family replacing the original family.

March Is National Celery Month

I think we can all agree there isn’t a more exciting food than celery! It’s light green! It’s mostly water! It doesn’t have a lot of flavor! Did I mention it’s mostly water?!

Okay, no matter how many exclamation points I use, I can’t get you pumped up for celery, but I happen to really love it (and not just with peanut butter spread on it). Here’s a recipe for Easy Homemade Chicken Salad from Genius Kitchen, which sounds good, though I think they might be overdoing it with the mustard, green peppers, and hard-boiled eggs. Here’s a simpler recipe from the same site.

I’ve noticed a lot of recipes include water chestnuts, but I wouldn’t go that route either. I do like white pepper in mine and maybe even some grapes. Yes, grapes.

Next Week’s Holidays and Events

Daylight Saving Time begins (March 11)

I hear there are people who like it when it stays light until 8 or 9 p.m. I’m not one of those people, but I know they exist. Set your clocks an hour ahead before you go to bed.

National Girl Scout Day (March 12)

How can you celebrate the day if you’re not a Girl Scout yourself? By purchasing some cookies, of course. I like the Samoas, which apparently are now called Caramel deLites.

The Right Way to Fall

Falls are one of life’s great overlooked perils. We fear terror attacks, shark bites, Ebola outbreaks, and other minutely remote dangers, yet over 646,000 people die worldwide each year after falling. Falls are the second leading cause of death by injury, after car accidents. In the United States, falls cause 32,000 fatalities a year (more than four times the number caused by drowning and fires combined). Nearly three times as many people die in the U.S. after falling as are murdered by firearms.

Falls are even more significant as a cause of injury. More patients go to emergency rooms in the U.S. after falling than from any other form of mishap, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), more than twice the number injured by car accidents. The cost is enormous. As well as taking up more than a third of ER budgets, fall-related injuries often lead to expensive personal injury claims. In one case in an Irish supermarket, a woman was awarded 1.4 million euros [approximately $1.6 million] compensation when she slipped on grapes inside the store.

It makes sense that falls dwarf most other hazards. To be shot or get in a car accident, you first need to be in the vicinity of a gun or a car. But falls can happen anywhere at any time to anyone.

The most dangerous spots for falls are not rooftops or cliffs, but the low-level interior settings of everyday life: shower stalls, supermarket aisles, and stairways. Any fall, even a tumble out of bed, can change life profoundly, taking someone from robust health to grave disability in less than one second.

Falling can cause bone fractures and, occasionally, injuries to internal organs, the brain, and the spinal cord. “Anybody can fall,” says Elliot J. Roth, co-medical director of the patient recovery unit at the Shirley Ryan AbilityLab in Chicago. “And most of the traumatic brain injury patients and spinal cord injury patients we see had no previous disability.”

There is no Journal of Falls, though research into falling, gait, and balance has increased tremendously over the past two decades. Advances in technology improve our understanding of how and why people fall, offer possibilities to mitigate the severity of falls, and improve medicine’s ability to treat those who have hurt themselves falling.

Scientists are now encouraging people to learn how to fall to minimize injury — to view falling not so much as an unexpected hazard to be avoided but as an inevitability to be prepared for.

You can trip or slip when walking, but someone standing stock still can fall too — because of a loss of consciousness, vertigo, or something supposedly solid giving way. However it happens, gravity takes hold and a brief violent drama begins. And like any drama, every fall has a beginning, middle, and end.

“We can think of falls as having three stages: initiation, descent, and impact,” says Stephen Robinovitch, a professor in the School of Engineering Science and the Department of Biomedical Physiology and Kinesiology at Simon Fraser University in British Columbia, Canada. “Most research in the area of falls relates to ‘balance maintenance’ — how we perform activities such as stand- ing, walking, and transferring without losing balance.”

By transferring, he means changing from one state to another: from walking to stopping, from lying in a bed to standing, or from standing to sitting in a chair. “We have found that falls among older adults in long-term care are just as likely to occur during standing and transferring as during walking,” says Robinovitch, who installed cameras in a pair of Canadian nursing homes and closely analyzed 227 falls over three years.

Only 3 percent were due to slips and 21 percent due to trips, compared to 41 percent caused by incorrect weight shifting — excessive sway during standing or missteps during walking. For instance, an elderly woman with a walker turns her upper body, and it moves forward while her feet remain planted. She topples over due to “freezing,” a common symptom of Parkinson’s experienced regularly by about half of those with the disease.

In general, elderly people are particularly prone to falls because they are more likely to have illnesses that affect their cognition, coordination, agility, and strength. “Almost anything that goes wrong with your brain or your muscles or joints is going to affect your balance,” says Fay Horak, professor of neurology at Oregon Health & Science University.

Fall injuries are the leading cause of death by injury in people over 60, Horak says. Every year, about 30 percent of those 65 and older living in senior residences have a fall, and when they get older than 80, that number rises to 50 percent. A third of those falls lead to injury, according to the CDC, with 5 percent resulting in serious injury. It gets expensive. In 2012, the average hospitalization cost after a fall was $34,000.

How you prepare for the possibility of falling, what you do when falling, what you hit after falling — all determine whether and how severely you are hurt. And what condition you are in is key. A Yale School of Medicine study of 754 over-70s, published in the Journal of the American Medical Association in 2013, found that the more serious a disability you have beforehand, the more likely you will be severely hurt by a fall. Even what you eat is a factor: A study of more than 12,000 elderly French people in 2015 found a connection between poor nutrition and falling or being hurt in falls.

“Over one-half of older adults who fall are unable to rise independently, and are at risk for a ‘long lie’ after a fall, especially if they live alone, which can greatly increase the clinical consequences of the falls,” Robinovitch says. He and his colleagues are working to develop wearable sensor systems that detect falls with high accuracy, as well as providing information on their causes, and on near-falls.

Not that a device needs to be high-tech to mitigate falls. Wrestlers use mats because they expect to fall; running backs wear pads. Given that a person over 70 is three times as likely to experience a fatal fall as someone younger, why don’t elderly people generally use either?

The potential benefit of cushioning is certainly there. e CDC estimates that $31 billion a year is spent on medical care for over-65s injured in falls — $10 billion for hip fractures alone (90 percent of which are due to falls). Studies show that such pads reduce the harmful effects of falling.

But older people have all the vanity, inhibition, forget fulness, wishful thinking, and lack of caution that younger people have, and won’t wear pads. More are carrying canes and using walkers than before, but many more who could benefit shun them because, to them, canes and walkers imply infirmity. This sets up another vicious cycle related to falling: Fearing the appearance of disability, some elderly people refuse to use canes, thereby increasing their chances of falling and becoming disabled.

One unexpected piece of anti-fall technology is the hearing aid. While the inner ear’s vestibular system is maintaining balance, sound itself also seems to have a role.

“We definitely found that individuals with hearing loss had more dificulty with balance and gait and showed significant improvement when they had a hearing aid,” says Linda Thibodeau, a professor at the University of Texas at Dallas’s Advanced Hearing Research Center, summarizing a recent pilot study. “Most people don’t know about this.”

Thibodeau says one reason it’s important to establish this link is that insurance companies don’t typically cover hearing aids, because they are seen as improving lifestyle more than sustaining basic health. Hearing aids can be expensive — up to $4,000 each — but a broken hip, which insurance companies do cover, can cost 5 or 10 times that figure or more and lead to profound disability or death.

Nearly half of people in their 70s have hearing loss but typically wait 10 to 20 years beyond the time when they could first benefit before they seek treatment. If the connection to balance and falls were better known, that delay might be reduced.

Given the tremendous cost of falls to individuals and society, and the increasing knowledge of how and why falls occur, what can you do to prevent them? And can you do anything to lessen harm in the split second after you start to fall?

1. Prepare Your Environment

Secure loose rugs or get rid of them. Make sure the tops and bottoms of stairs are lit. Clean up spills immediately. Install safety bars in showers and put down traction strips, and treat slick surfaces such as smooth marble floors with anti-slip coatings. If there’s ice outside your home, clear it and put down salt.

2. Fall-Proof Your Routine

Watch where you are going. Don’t walk while reading or using your phone. Always hold handrails — most people using stairways do not. Don’t have your hands in your pockets, as this reduces your ability to regain your balance when you stumble. Remember that your balance can be thrown off by a heavy suitcase, backpack, or bag.

Roth asks most of his patients who have fallen to describe in detail what happened. “Sometimes people are not paying attention. Multitasking is a myth, and people should try very hard to avoid multitasking. No texting while walking.”

3. Improve Your Gear

Wear good shoes with treads. On ice, wear cleats — you can buy inexpensive soles with metal studs that slip over your shoes. Do not wear high heels, or at least have a second pair of flat shoes for walking between locations. Get a hearing aid if you need one. Wear a helmet when bicycling, skiing, and skateboarding. Use a cane or walker if required. Hike with a walking stick.

4. Prepare Your Body

Lower body strength is important for recovering from slips, upper body strength for surviving falls. Martial arts training can help you learn how to fall. Drugs and alcohol are obviously a factor in falls — more than half of adult falls are associated with alcohol use — as is sleep apnea. Get a balanced diet to support bone density and muscle strength. If you feel light-headed or faint, sit down immediately. Don’t worry about the social graces; you can get back up once you’ve established you are not going to lose consciousness.

Understandably, some elderly people fear falling so much that they don’t even want to contemplate it. “People should know they could improve their balance with practice, even if they have a neurological problem,” Horak says.

5. Fall the Right Way

What happens once you are falling? Scientists studying falling are developing “safe landing responses” to help limit the damage from falls. If you are falling, first protect your head — 37 percent of falls by elderly people in a study by Robinovitch and colleagues involved hitting their heads, particularly during falls forward. Fight trainers and parachute jump coaches encourage people to try not to fall straight forward or backward. The key is to roll, and try to let the fleshy side parts of your body absorb the impact.

“You want to reach back for the floor with your hands,” says Chuck Coyl, a theatrical fight director out of Chicago, describing how he tells actors to fall on stage. “Distribute the weight on the calf, thigh, into the glutes, rolling on the outside of your leg as opposed to falling straight back.”

Young people break their wrists because they shoot their hands out quickly when falling. Older people break their hips because they don’t get their hands out quickly enough. You’d much rather break a wrist than a hip.

Neil Steinberg is a columnist on staff at the Chicago Sun-Times. He has written for Esquire, Rolling Stone, Forbes, The Washington Post, and many other publications.

This article is featured in the January/February 2018 issue of The Saturday Evening Post. Subscribe to the magazine for more art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

Adapted from the original article first published by Wellcome on Mosaic and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.

An Interview with Hans Zimmer, Hollywood’s Hottest Composer

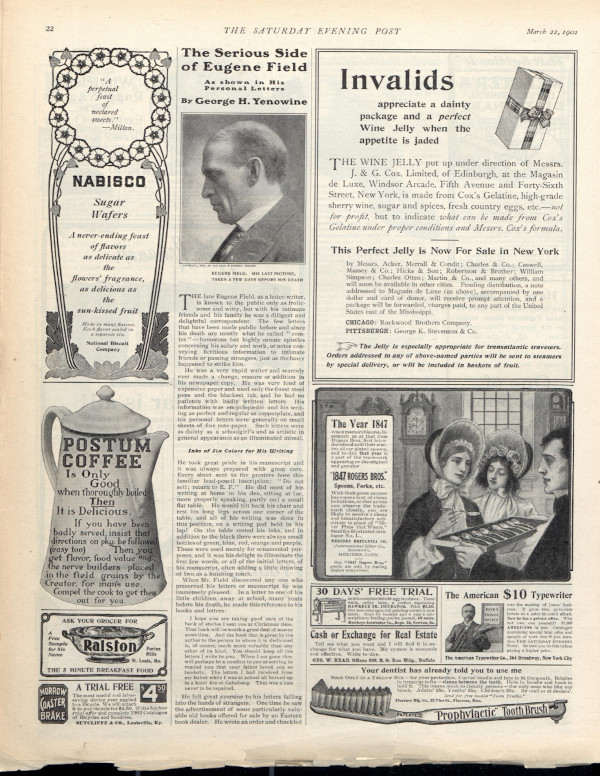

Hans Zimmer is one of Hollywood’s most successful and innovative composers, with soundtracks for over 150 films ranging from Driving Miss Daisy to Gladiator to the current Oscar frontrunner, Dunkirk. Zimmer’s original score for The Lion King earned him an Academy Award; he’s been nominated for eight more.

The celebrated musician fought past his life-long stage fright to give a show-stopping performance on last year’s Grammy Awards, providing guitar riffs for Pharrell Williams. That inspired a world tour, giving enthusiastic audiences live performances of the powerful musical moments they first experienced in a dark theater. He was a surprise hit at Coachella alongside mega-stars like Kendrick Lamar and Lady Gaga.

Since he was a kid, Zimmer just wanted to make music. “My father died when I was really young, so growing up, music was a refuge for me,” he remembers.

“Then when you become a teenager, it turns into a completely different thing. It becomes — how am I going to say this politely? – when it comes to girls, it’s better than talking to them.”

Jeanne Wolf: Now that your live show is a hit, can I finally call you a rock star?

Hans Zimmer: I don’t think I’m a rock star but it is exciting to go out there and play in front of people instead of hiding behind a movie screen. I have a feeling that it might have made me a better composer, because I was actually able to feel the audience in real time rather than what we do making movies, where we’re basically guessing. We’re hoping that the soundtrack we’re creating is going to resonate and add to the experience for people in a theater. As soon as I finish a movie, I forget everything that I’ve written. I have to forget, because otherwise you don’t make room for the new ideas. So when we are playing the old soundtracks every night on tour, we are reinventing and sort of improving them. That’s a luxury you don’t have when you’re making a film.

JW: There has been a remarkable reaction to your compositions for the movie Dunkirk. The suspense-driving track is so unique that it’s hard to describe. Where did that come from?

HZ: Usually I start out by writing a tune, but there’s no melody in the Dunkirk soundtrack. The whole idea was how do we keep the tension going? How do we play with the concept that time is running out? Everything had to live up to that. For months I would go to sleep, and I would start dreaming the scenes, and then I would wake up and go back to the studio. I never had any reprieve from it. When I actually went on the Dunkirk location, the weather had turned really nasty. I was on that beach, and it was unbearably cold. Sand was blowing at you from every direction, the poor actors were standing there in the freezing wind, and there’s [director] Chris Nolan charging down the beach. So when I was composing, I felt Chris’ hand on my hand like he was pressing the keys down with me. I really tried as much as possible to make it his score.

JW: With all you’ve done, I always love your enthusiasm.

HZ: The operative word in music is play. The thing that we really carry over from our childhood is that sense of playfulness. I think all that happens is we try to get very serious about being very playful. The hours we keep are absurd. I’m forever begging forgiveness of my children for not being around, but on the other hand, they love being in my studio. I think what my kids have seen through their whole childhood watching me work is people being passionate about what they’re doing and having fun, having a sense of humor about a catastrophe (which isn’t really a catastrophe). Making movies, there’s never enough time, never enough money, it’s raining on the day you need sunshine, and it’s sunny on the day you’re trying to shoot a rain scene. I sort of make it my job in a funny way to remind the filmmakers what the original dream was and enhance it. I think about what made every body try to do the impossible.

JW: I have interviewed a lot of rock stars, and they talk about that high when you connect with the audience. Did you experience that kind of connection?

HZ: Constantly, constantly. Yes, absolutely. I mean, I really felt that the audience was hungry to have a different experience, and we managed to give them that. They had a sort of idea what it would be like, but to be honest, no one has ever done it this way, so the element of surprise was really nice, and the element of surprise for me was really nice. Just how open they were and how welcoming they were. I asked everybody for advice before this, and people kept saying that the attention span of young people is really bad these days, and you have to play short pieces. I don’t know. “Pirates” is 14 minutes long. “The Dark Knight” thing is 22 minutes long. These aren’t short pieces, and the audience really stuck with it. The audience loved that we would take them on a journey and take them back into the world.

JW: How great was that? You are still so excited about what you do. I love your participation. Could you describe what drives you now?

HZ: Yes. Actually what was interesting for this tour was going back. Obviously, I had to go back in time and look at all of the pieces that I’ve written. The tour was playing the old soundtracks again, and every night we were reinventing and sort of improving them. All of the stuff that you can’t do because you have time restrictions. A movie needs to be finished.

JW: And you have to fit to the scene.

HZ: Exactly. So what drives me is basically that I know I can write a better piece of music. I know I’m still learning and figuring it out. Dunkirk was such a learning curve because we really reached through every rule book. It wasn’t even about “Let’s invent a new way of doing this.” It was “Let’s invent and then we actually have to learn how to do it.” Every day was a day of having no idea of how to get around the next corner.

JW: Listening is a big part of your art. Do you think you’re a good listener with the people close to you? Because it’s hard to be nowadays.

HZ: I think I try to be a good listener. My children keep telling me that — so that’s the greatest compliment that I can get.

JW: That is a great compliment. It means you’re hearing me and you understand me.

HZ: Yes, exactly. I suppose you know, partly the reason I have the career I’ve had is that I listen to my directors. I don’t listen when they tell me what to do. I listen to the subtext. I listen to what the —. Look, every movie starts with the same thing. Somebody phones you up and says, “I want to tell you a story,” which is already a great start. What a great life — these people telling me stories.

JW: Has there been a director — there must be more than one — whom you butt heads with or think you’ll never be able to please?

HZ: Oh totally. Often. Those are the directors that I’ve worked with more than once. Gore Verbinsky and I would go at each other pretty badly. Terry Malick once said to me, “The way we speak to each other, only brothers can speak to one another that way.” I remember I was doing Hannibal, working with Ridley Scott. It was about 11 o’clock on a Sunday night. They had just gotten back from shooting, and we were in the cutting room looking at a shot of Julianne Moore’s face with a tear running down her cheek, and I say, “Oh yeah, she’s crying because she’s in love with him.” And Ridley goes, “No. It’s a tear of disgust.” Then we start arguing about this and it got sort of feisty, and suddenly we’re on our feet and we’re in each other’s faces and I just stepped back and I thought, Wow. This is amazing. It’s Sunday night at 11 o’clock and grown men are passionately arguing about what a tear running down a woman’s cheek means.

JW: Have you figured out where you got your courage?

HZ: Well, I think from the people who were kind and took me on when I had no career. Stanley Myers, the great film composer who wrote The Deer Hunter, he took me under his wing. One of the first people I ever got to work with. I also learned a lot from George Martin.

JW: Oh! The Beatles man.

HZ: I remember the first time I ever got paid for doing music was for George Martin. Weirdly, I remember the check more than the sessions. It was astonishing after struggling. I can’t tell you how many tins of baked beans I ate because it was the only thing I could afford. Somebody was actually paying me to make music.

JW: Wow. How many tins of baked beans did it take to be here?

HZ: Years.

JW: The people don’t understand that the memory of that gives you courage, too.

HZ: My daughter asked me once, “Dad, what was it like being a poor artist?” I realized that I’d never thought about it. It never occurred to me that I was a poor artist because everybody around me was in the same boat. That just seemed to be life, and we were making music all day long. I still have really bad eating habits. I usually don’t have lunch because I’m in the middle of writing something. Do I live a normal life? No. Look, I’m coming up to my 60th birthday, and I think it has worked out so far.

JW: Yes. Oh, boy, has it. We want a full life, but do we really want what someone else defines as a normal life? No. Not somebody who goes to play Coachella.

HZ: No, and the world is shifting tremendously with technology and stuff like this. So many things which we took for granted that came from the Industrial Revolution — like job security — are just disappearing, and I think at the end of the day the one thing that isn’t disappearing is to be an artist. To write poetry, to paint a painting, to write music.

JW: Could you have dreamed that you would be as excited, as turned on, as buzzed about what you do now as you were in the beginning — or more!

HZ: Yes. I don’t know why. Well actually, I have to say, and every director knows this about me, I do a little thing where I ask myself when I get up, “What if I was to go to the studio today to make music, and the answer is ‘No, we need to find somebody else.’” But it hasn’t happened yet. Literally, the last four weeks of the tour we were so tired, but all I was doing was planning the next piece of music and the next adventure. That’s just how I’m built, and everybody around me is sort of built that way as well.

An abridged version of this article is featured in the November/December 2017 issue of The Saturday Evening Post. Subscribe to the magazine for more art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

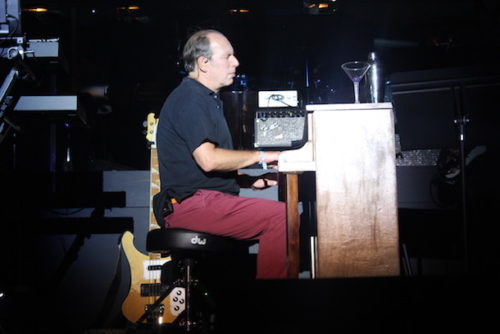

Joe College Is Dead: The Root of Student Unrest in the 1960s

[Editor’s note: Arthur Schlesinger Jr.’s “Joe College Is Dead” was first published in the September 21, 1968, edition of the Post. We republish it here as part of our 50th anniversary commemoration of the Summer of Love. Scroll to the bottom to see this story as it appeared in the magazine.]

Miriam Bakser, © SEPS

Throughout our history, our sons and daughters have been the bearers of our aspirations, commissioned by birth to fulfill our dreams. Today, more than ever before in any country, the indispensable climax of the children’s preparation — and the parents’ hope — is college. “Going to college” is now considered the key to life — the key not only to intellectual training but to social status and economic success.

The United States today has nearly 6 million college students — 46 percent of all young people from 18 to 21. By 1970 we are expected to have 7.5 million — which means that our student population will have more than doubled in the single decade of the ’60s. Yet, the more college students we have, the more baffling they seem to become. For years, adults saw college life in a panorama of reassuring images, derived from their own sentimental memories (or from the movies) — big men on campus, fraternities and sororities, junior proms, goldfish swallowing, panty raids, winning one for the Gipper, tearing down goalposts after the Big Game, homecoming. College represented the “best years of life,” a time of innocent frivolity and high jinks regarded by the old with easy indulgence. But the familiar stereotypes don’t work anymore. The new undergraduate seems a strange, even a menacing, phenomenon, consumed with mysterious resentments, committed to frenetic agitations.

Many adults look on college students today as spoiled and ungrateful kids who don’t know how lucky they are to be born in the greatest country on earth. Even men long identified with liberal views find the new undergraduate, in his extreme manifestations, almost unbearable. The hard-working student, Vice President Hubert Humphrey tells us, “is being replaced on our living-room televisions by the shouter of obscenities and hate.” President Nathan M. Pusey of Harvard speaks of “Walter Mittys of the left … [who] play at being revolutionaries and fancy themselves rising to positions of command atop the debris as the structures of society come crashing down.” George F. Kennan talks of “banners and epithets and obscenities and virtually meaningless slogans … screaming tantrums and brawling in the streets.” Yet the very magnitude of student discontent makes it hard to blame the trouble on individual malcontents and neurotics. A society that produces such an angry reaction among so many of its young people perhaps has some questions to ask itself.

Obviously most of today’s students came to college to prepare themselves to earn a living. Most still have the same political and economic views as their parents. Most, until 1968, supported military escalation in Vietnam. Most believe safely in God, law and order, the Republican and Democratic parties, and the capitalist system. Some may even tear down goalposts and swallow goldfish, if only to keep their parents happy.

Yet something sets these students apart from their elders — both in the United States and in much of the developed world. For this college generation has grown up in an era when the rate of social change has been faster than ever before. This constant acceleration in the velocity of history means that lives alter with startling and irresistible rapidity, that inherited ideas and institutions live in constant jeopardy of technological obsolescence. For an older generation, change was still something of a historical abstraction, dramatized in occasional spectacular innovations, like the automobile or the airplane; it was not a daily threat to identity. For our children, it is the vivid, continuous, overpowering fact of everyday life, suffusing every moment with tension and therefore, for the sensitive, intensifying the individual search for identity and meaning. The very indispensability of a college education for success in life compounds the tension; one has only to watch high-school seniors worrying about the fate of their college applications.

Nor does one have to be a devout McLuhanite to accept Marshall McLuhan’s emphasis on the fact that this is the first generation to have grown up in the electronic epoch. Television affects our children by its rapid and early communication to them of styles and possibilities of life, as well as by its horrid relish of crime and cruelty. But it affects the young far more fundamentally by creating new modes of perception. What McLuhan has called “the instantaneous world of electric informational media” alters basically the way people perceive their experience. Where print culture gave experience a frame, McLuhan has argued, providing it with a logical sequence and a sense of distance, electronic communication is simultaneous and collective; it “involves all of us all at once.” This is why the children of the television age differ more from their parents than their parents differed from their own fathers and mothers. Both older generations, after all, were nurtured in the same typographical culture.

Another factor distinguishes this generation — its affluence. The postwar rise in college enrollment in America, it should be noted, comes not from any dramatic increase in the number of youngsters from poor families but from sweeping in the remaining children of the middle class. And for these sons and daughters of the comfortable, status and affluence are, in the words of student radical leader Tom Hayden, “facts of life, not goals to be striven for.” This puts many students in a position to resist economic pressures to buckle down and conform. As another radical has written, “Our minds have been let loose to try to fill up the meaning that used to be filled by economic necessity.”

The velocity of history, the electronic revolution, the affluent society — these have given today’s college students a distinctive outlook on the world. And a fourth fact must not be forgotten: that this generation has grown up in an age of chronic violence. My generation has been through depressions, crime waves, riots and wars; but for us episodes of violence remain abnormalities. For the young, the environment of violence has become normal. They are the first generation of the nuclear age — the children of Hiroshima. The United States has been at war as long as many of them can remember — and the Vietnam war has been a particularly brutalizing war. Most students have come to feel that the insensate destruction we have wrought in a rural Asian country 10,000 miles away has far outrun any rational assessment of our national interest. Within the United States, moreover, they have lived with the possibility, as long as many of them can remember, of violence provoked by racial injustice. Even casual crime has acquired a new dimension. Some have never known a time when it was safe to walk down the streets of their home city at night. Above all, they have seen the assassinations of three men who embodied the idealism of American life. The impact of this can hardly be overstated. And — let us face it — our national reaction to these horrors has only strengthened their disenchantment: brief remorse followed by business as usual and the National Rifle Association triumphant.

The combination of these factors has given the young both an immediacy of involvement in society and a sense of their individual helplessness in the face of the social juggernaut. The highly organized modern state undermines their feelings of personal identity by threatening to turn them all into interchangeable numbers on IBM cards. Contemporary industrial democracies stifle identity in one way, Communist states in another, but the sense of impotence is all-pervasive among the young. So too, therefore, is the desperate passion to reestablish identity and potency by assaults upon the system.

Such factors have set off the guerrilla warfare of students against the existing structures of society not only in the United States but throughout the developed world. (Student unrest in underdeveloped countries is more predictable and has different sources.) Uprisings at Berkeley and Columbia are paralleled by uprisings at the Sorbonne and Nanterre, in the universities of England and Italy, in Spain and Yugoslavia and Poland, in Brazil and Japan and China. Every country can offer local grievances to detonate local revolts. But these are only the pretexts for the rebellion. They are the visible symbols for what the young perceive as the deeper absurdity and depravity of their societies.

American undergraduates first fixed on racial injustice as the emblem of a corrupt society. But in the last two years, resistance to the draft has provided a main outlet for undergraduate revolt.

Until very recently, most college students supported the war in Vietnam — so long as other young men were fighting it. It used to exasperate Robert Kennedy when he asked college audiences in 1966 and 1967 what they thought we should do in Vietnam — hands waving for escalation — and then asked what they thought of student deferment — the same hands waving for a safe haven for themselves. At last, as the draft began to cut deeper, the colleges began to think about the war; and the more they thought about it, the less sense it made.

No one should underestimate the magnitude of this new anti-draft feeling. In 1968, I have not encountered a single student who still supports military escalation in Vietnam. Not all students who hate the war burn draft cards or flee to Canada. Many — and this may be as courageous a position as that of defiance — feel, after conscientious consideration, that they must respect laws with which they disagree, so long as the means to change these laws remain unimpaired. Yet even they regard with sympathy their friends who choose to resist. One who is himself prepared to go to Vietnam said to me, “Every student wants to avoid the draft. Every student, realizing that the method to this end is very individual, respects any method that works — or attempts that do not.”

The anti-draft revolt somewhat diminished this year after President Johnson’s March 31st speech, the Paris negotiations and the McCarthy and Kennedy campaigns. But it will resume, and with new ferocity, if the next President intensifies the war. In April, The New York Times carried a four-page advertisement headed: “We, Presidents of Student Government and Editors of campus newspapers at more than 500 American colleges, believe that we should not be forced to fight in the Vietnam war because the Vietnam war is unjust and immoral.” In June, a hundred former presidents of college student bodies joined campus editors to declare, “We publicly and collectively express our intention to refuse induction and to aid and support those who decide to refuse. We will not serve in the military as long as the war in Vietnam continues.”

However, if we Americans blame the trouble on the campuses just on the war (or, to take another popular theory, on permissive ideas about childrearing), we will not understand the reasons for turbulence. After all, the students of Paris were not rioting against a government that threatened to conscript them for a war in Vietnam; nor are the students of Poland, Spain, and Japan in revolt because their parents were devotees of Dr. Spock. The disquietude goes deeper, and it was well explained by, of all people, Charles de Gaulle. The “anguish of the young,” the old general said after his own troubles in June with French students, was “infinitely” natural in the mechanical society, the modern consumer society, because it does not offer them what they need, that is, an ideal, an impetus, a hope, and I think that ideal, that impetus, and that hope, they can and must find in participation.

Not every American student exemplifies this anguish. It appears, for example, more in large colleges than in small, more in good colleges than in bad, more in urban colleges than in rural, more in private and state than in denominational institutions, more in the humanities and social sciences than in the physical and technological sciences, more among bright than among mediocre students. Yet, as anyone who lectures on the college circuit can testify, the anguish has penetrated surprisingly widely — among chemists, engineers, Young Republicans, football players, and into those last strongholds of the received truth, the Catholic and fundamentalist colleges.

How to define this anguish? It begins with the students’ profound dislike for the impersonal society that produced them. The world, as it roars down on them, seems about to suppress their individualities and computerize their futures. They call it, if they vaguely accept it, “the rat race,” or, if they resist it, “The System” or “The Establishment.” They see it as a conspiracy against idealism in society and identity in themselves. An outburst on a recent Public Broadcast Laboratory program conveys the flavor. The System, one student said, hits at me through every single thing it does. It hits at me because it tells me what kind of a person I can be, that I have to wear shoes all the time, which I don’t have on right now. … It hits at me in every single way. It tells me what I have to do with my life. It tells me what kind of thoughts I can think. It tells me everything.

Another student added, with rhetorical bravado, “Regardless of what your alternatives are, until you destroy this system, you aren’t going to be able to create anything.”

The more typical expression of this mood is private and quiet. It takes the form of an unassuming but resolute passion to seize control of one’s own future. My generation had the illusion that man made himself through his opportunities (Franklin D. Roosevelt); but this era has imposed on our children the belief that man makes himself through his choices (Jean-Paul Sartre). They now want, with a terrible urgency, to give their own choices transcendental meaning. They have moved beyond the Bohemian self-indulgence of a decade ago — Allen Ginsberg and Jack Kerouac. “We do not feel like a cool swinging generation,” a Radcliffe senior said this year in a commencement prayer. “We are eaten up by an intensity that we cannot name. Somehow this year, more than others, we have had to draw lines, to try to find an absolute right with which we could identify ourselves. First in the face of the daily killings and draft calls … then with the assassinations of Martin Luther King and Senator Kennedy.”

The contemporary student generation can see nothing better than to act on impulses of truth: “Ici, on sponlane,” as a French student wrote on the walls of his college during the Paris insurgency. They are going to tell it, as they say, like it is, to reject the established complacencies and hypocrisies of their inherited existence. One student said to me:

Basically, the concept of this “do your thing” bit, as ludicrous as it sounds, may be the key to the matter. What it means is similar to Mill’s On Liberty because it allows anybody to do what he wants to do as long as it does not intrude on anyone else’s liberty. Therefore, nobody tries to impose anything on anybody, nor do they not accept a Negro, a hippie, a clubby, etc. I really believe that today we see beyond superficial appearances and thus, in the end, will have a society of very divergent styles, but it will be successfully integrated into a really viable whole. . . . We test out old thoughts and customs and either dispose of them or retain them according to their merits.

Along with this comes an insistence on openness and authenticity in personal relationships. A 1968 graduate — a girl — puts it clearly:

I think in personal conduct people admire the ability to be vulnerable. That takes a certain amount of strength, but it is the only thing which makes honesty and openness possible. It means you say the truth and somehow leave open a part of your way of thinking. Of course, you cannot be vulnerable with everyone or you would destroy yourself — but it is the willingness to be open, not just California-cheerful open, which is almost a mask since it is on all the time, and therefore cannot be truthful. It is a little deeper than that. … It means being strong enough to reveal your weaknesses. This willingness to be vulnerable — and those you are vulnerable with are your friends — coupled with ability to be resilient, to be strong but supple, those are good qualities, because inherent in them are honesty and humor, and the good capacity to love.

This is the ethos of the young — a commitment not to abstract pieties but to concrete and immediate acts of integrity. It leads to a desire to prove oneself by action and participation — whether in the Peace Corps and VISTA or in the trials of everyday existence. The young prefer performance to platitude. The self-serving rhetoric of our society bores and exasperates them, and those who live by this rhetoric — e.g., their parents — lose their respect.

It is understandably difficult for parents, who have worked hard for their children and their communities, to see themselves as smug and hypocritical. But it is also understandable that the children of the ’60s should have grown sensitive to the gap between what their parents say their values are and what (as the young see it) their values really are. The gap has been made vivid in the way the land of freedom and equality so long and unthinkingly condemned the Negro to tenth-class citizenship. “It is quite right that the young should talk about us as hypocrites,” Judge Charles E. Wyzanski Jr. recently said at Lake Forest College. “We are.”

And more often than they know, parents themselves unconsciously reveal to their children a cynicism about the system or a disgust for it. Every father who bewails the tensions of the competitive, acquisitive life, who says he “lives for the weekend,” who conveys to his children the sense that his life is unfulfilled — they are all, as Prof. Kenneth Keniston of Yale has put it, “unwittingly engaged in social criticism.” Sometimes these frustrated parents find compensation in the rebellion of their young. There is even what one observer has described as the “my son, the revolutionary” reaction of proud parents, like the mother of Mark Rudd, the Columbia student firebrand who emerged in the spring of 1968 as the Che Guevara of Morningside Heights.

Today’s students are not generally mad at their parents. Often they regard their father and mother with a certain compassion as victims of the system that they themselves are determined to resist. In many cases — and this is even true of the militant students — they are only applying the values that their parents affirmed; they are not rebelling against their parents’ attitudes but extending them. Revolt against parents is no longer a big issue. There is so little to revolt against. Seventy-five years ago parents had unquestioning confidence in a set of rather stern values. They knew what was right and what was wrong. Contemporary parents themselves have been swept along too much by the speed-up of modern life to be sure of anything. They may be square, but they are generally too doubtful and diffident to impose their squareness on their children.

Parents today are not so much intrusive as irrelevant. Mike Nichols caught one student’s-eye view of his elders beautifully in The Graduate, with his portrait, so cherished by college students today, of a shy young man freaked out by the surrounding world of towering, braying, pathetic adults. A girl who finished college last June sums it up:

People like their parents as long as their parents do not interfere a whole lot, putting pressure on choice of careers, grades, personal life. … I think freshmen tend to discuss and dislike their parents more than seniors. By then, supposedly, you have some distance on them, and you can afford to be amused or affectionate about them. For instance, if your parents are for Reagan or were for Goldwater, you know the space between you and them on it, and the impossibility of crossing it, so you let them go their imbecilic way and stand back amused. Other people say that they really like their parents. But nobody wants to go back home. For any length of time, it is usually a bad trip.

One student even looks forward to an ultimate “communion of interests” between today’s students and their parents, only “with the younger half having gone through more (which may be necessary in this more complicated, difficult, tense, scary world) to get to the same place.”

No, the boys and girls of the 1960s, unlike the heroes and heroines of Dreiser, Lewis, Fitzgerald and Wolfe, are not targeted against their parents. Their determination is to reject the set of impersonal institutions — the “structures”— which also victimize their parents. And the most convenient “structure” for them to reject is inevitably the college in which they live. In doing so, they construct plausible academic reasons to justify their rejection — classes too large, professors too inaccessible, curricula too rigid, and so on. One wonders, though, whether educational reform is the real reason for student self-assertion, or just a handy one. One sometimes suspects that the fashionable cry against Clark Kerr’s “multiversity” is a pretext, and one doubts whether students today would really prefer to sit on a log with Mark Hopkins.

This does not mean that “student power” is a fake issue. But the students’ object is only incidentally educational reform. Their essential purpose is to show the authorities that they exist as human beings and, through a democratization of the colleges, to increase control of their lives. For one of the oddities about the American system is the fact that American higher education, that extraordinary force for the modernization of society, has never modernized itself. Harold Howe II, the federal Commissioner of Education, has pointed out that “professors who live in the realm of higher education and largely control it are boldly reshaping the world outside the campus gates while neglecting to make corresponding changes to the world within.” Students cannot understand “why university professors who are responsible for the reach into space, for splitting the atom, and for the interpretation of man’s journey on earth seem unable to find the way to make the university pertinent to their lives.”

An “academic revolution” has taken place in recent years; but in some senses it has only made the problem worse. As analyzed by David Riesman and Christopher Jencks in their recent book by that name, it involves the increasing domination of undergraduate education by the methods and values of graduate education. Many professors are more concerned with colleagues than with students, thus increasing the undergraduate longing, in the words of Riesman and Jencks, for “a sense that an adult takes them seriously, and indeed that they have some kind of power over adults which at least partially offsets the power adults obviously have over them.”

Academic government, in most cases, is strictly autocratic. Some colleges still operate according to rules appropriate to the boys’ academies that most of our colleges essentially were in the early 19th century. A Harvard professor, modifying a famous phrase, once described his institution as “a despotism not tempered by the fear of assassination.” As a Columbia student recently put it, “American colleges and universities (with a few exceptions, such as Antioch) are about as democratic as Saudi Arabia.” The students at Columbia, he adds, were “simply fighting for what Americans fought for two centuries ago — the right to govern themselves.”

What does this right imply? At Berkeley students boldly advocated the principle of cogobierno — joint government by students and faculties. This principle has effectively ruined the universities of Latin America, and no sensible person would wish to apply it to the United States. However, many forms of student participation are conceivable short of cogobierno — student membership, for example, on boards of trustees, student control of discipline, housing and other nonacademic matters, student consultation on curriculum and examinations. These student demands may he novel, but they are hardly unreasonable. Yet most college administrations for years have rejected them with about as much consideration as Sukarno, say, would have given to a petition from a crowd of Indonesian peasants.

One can hardly overstate the years of student docility under this traditional and bland academic tyranny. It was only seven years ago that David Riesman, as a professor noting undergraduate complaints about college and society, wrote, “When I ask such students what they have done about these things, they are surprised at the very thought they could do anything. They think I am joking when I suggest that, if things came to the worst, they could picket!” But the careful student generation of the ’50s was already passing away. Soon John F. Kennedy, the civil-rights freedom riders, then the Vietnam war, stirred the campuses into new life. Still college presidents and deans ignored the signs of protest. The result inevitably has been to hand the initiative to student extremists, who seek to prove that force is the only way to make complacent administrators and preoccupied professors listen to legitimate grievances. “Our aim,” as an Oxford student leader put it, “is to completely democratize the University. We shall look for cases on which we can confront authoritarianism in colleges, faculties, and the University.” Or, in the words of Mark Rudd of Columbia: “Our style of politics is to clarify the enemy, to put him up against the wall.”

The present spearhead of undergraduate extremism is that strange organization, or nonorganization, called Students for a Democratic Society. S.D.S. began half a dozen years ago as a rather thoughtful movement of student radicals. Its Port Huron statement of June, 1962, a humane and interesting if interminable document, introduced “participatory democracy” — that is, active individual participation “in those social decisions determining the quality and direction of his life” — as the student’s solution to contemporary perplexities. In these years S.D.S. performed valuable work in combating discrimination and poverty; and this work generated a remarkable feeling of fellowship among those involved. But the Port Huron statement no longer expresses official SDS policy; and SDS itself has become an excellent example of what Lenin, complaining about left-wing Communism in 1919, called “an infantile disorder.”

This is not to suggest that SDS is Communist, even if it contains Maoist and Castroite (or Guevaraite) factions. The basic thrust of SDS is, if anything, syndicalist and anarchistic, though the historical illiteracy of its leadership assures it a most confused and erratic form of anarcho-syndicalism. The anarchistic impulse extends to its organization — the infatuation with decentralization is so great that there is none (the joke is “the Communists can’t take over S.D.S. — they can’t find it”) — as well as to its program. The infatuation with the creative power of immediate action is so great that there is none.

Anarchism, with its unrelenting assault on all forms of authority, is a natural adolescent response to a world of structures. As a French student scribbled on the wall of his university at Nanterre, “L’anarchie, c’est je.” But the danger of anarchism has always been that, lacking rational goals, it moves toward nihilism. The strategy of confrontation turns into a strategy of provocation, intended to drive authority into acts of suppression supposed to reveal the “hidden violence” and true nature of society. Confrontation politics requires both an internal sense of infallibility and an external insistence on discipline. Soon the SDS people began to show themselves, as one student put it to me, “exclusionary, self-righteous, and single-minded. I feel that they, along with certain McCarthy people, are the one group that does not think that everybody should do their thing, but rather do the SDS thing.” In time SDS virtually rejected participatory democracy. Prof. William Appleman Williams of Wisconsin, whose own historical writing stimulated this generation of student radicals, ended by calling them “the most selfish people I know. They just terrify me. … They say, ‘I’m right and you’re wrong and you can’t talk because you’re wrong.’”

In 1967, SDS began to discuss in its workshops how confrontation politics — seizing buildings, taking hostages, and so on — could be used to bring down a great university and selected Columbia as its 1968 target. The result was the uprising last April, which brutal police intervention transformed from an SDS Putsch into a general student insurrection. At Columbia, the SDS leaders displayed no interest in negotiating the ostensible issues. Their interest was power. “If we win,” said Mark Rudd, the SDS leader, “we will take control of your world, your corporation, your university and attempt to mold a world in which we and other people can live as human beings. Your power is directly threatened, since we will have to destroy that power before we can take over.” For the sake of power, they were prepared, as a liberal Columbia professor put it, to “exact a conformity that makes Joe McCarthy look like a civil libertarian.”

As the SDS leaders get increasing kicks out of their revolutionary rhetoric, they have grown mindless, arrogant and, at times, vicious in their treatment of others. In recent months, the young men who incite riot and talk revolution have encouraged acts of exceptional squalor — not only the denial of free speech but the rifling of personal files, the destruction of the research notes of an unpopular professor — in fact, a general commitment not to university reform but to destruction for the sake of destruction. Their influence is to turn students into what John Osborne, one of Britain’s “angry young men” of the ’50s, has called “instant rabble.” Their effect is to betray the function of the university, which is nothing if not a place of unfettered inquiry, and to repudiate the western tradition of intellectual freedom.

What sort of factor will SDS be in the future? No one, including its own national office, can be sure how many members SDS has. J. Edgar Hoover, who is not addicted to minimizing the enemy, told Congress on February 23 that in 1967 SDS had 6,371 members, of whom 875 had paid dues since January 1. Whatever the number, it is an infinitesimal fraction of the American college population. Yet this fact should not induce undue complacency in the country clubs. Many students who would never dream of joining SDS or of approving its tactics nevertheless share its sense of estrangement from American society. This spring the Gallup Poll reported that one student in five had taken part in protest demonstrations — a statistic that suggests not only that a million students may he counted as activists but that the proportion has probably doubled since the estimates of student rebels in the spring of 1966 as 1 in 10 (Samuel Luhell) and 1 in 12 (the Educational Testing Service). All studies, moreover, indicate that the activists are good students and that they abound in the best universities.

What is significant is not only the rather large number of student activists today but their success in winning the tacit consent of the less involved. This does not mean that the majority applauds the gratuitous violence that has swept through many institutions. But activists very often appear to mirror general student concerns and anxieties on a wide range of issues, social and political as well as academic.

A recent episode at Antioch explains why the majority goes along with the activists. Although on other campuses it is considered a paragon of democracy — its students, for example, can attend the meetings of its board of trustees — this fine old experimental college in Yellow Springs, Ohio, evidently still has problems of its own. A year ago the board of trustees met before an audience of some 75 students. One member began to read the report of the committee on the college investments. As he droned along, a student suddenly jumped up and shouted, “This is all a lot of ———“ A second student then arose and said, with elaborate irony, “You shouldn’t talk that way. These wonderful trustees are giving of their time and substance to help us out.” Next, in quick succession, half a dozen other students got up and called caustic single sentences at the startled trustees. At this point, the lights went out. When they came on 30 seconds later, the trustees were confronted by a tableau: one masked student standing with his foot on the chest of another masked student prostrate on the floor. The boy on the floor said, “Massa, is it all right if I use LSD?” The standing student replied, parodying a phrase cherished by academic administrators, “It is all right if you follow institutional processes.” A series of similar Qs and As followed. The lights went out again; there were sounds of scurrying; and, when the lights came on, all but a dozen students had gone.

A moment of silence followed. Then the trustee who had been reading the report from the committee on investments resumed exactly where he had left off. This was too much for a colleague, who broke in and said reasonably, “Mr. Chairman, I don’t think that we ought to act as if nothing had happened.” The chairman asked what he proposed, and the trustee suggested that they invite the students who had remained to tell them what this demonstration had been all about. The students still in the room responded that, while they had not approved of the demonstration, they were now delighted that it had forced the trustees to listen to them. “You may not like what you saw,” one student remarked. “But now you are discussing things that you would never be discussing on your own initiative.” And for the first time the Antioch board of trustees permitted on its agenda some of the problems that were worrying the Antioch students.

This story illustrates a disastrous paradox: The extremist approach works. “I feel like I just wasted three and a half years trying to change this university,” a Columbia senior said after the troubles last spring. “I played the game of rational discourse and persuasion. Now there’s a mood of reconstruction. All the log-jams are broken — violence pays. The tactics of obstruction weren’t right, weren’t justified, but look what happened.” The activists understand what has until recently escaped the attention of the deans — that a small number of undergraduates, if they don’t give a damn, can shut down great and ancient universities. As a result, when the activists turn on, the administrators at last begin to do things which, if they had any sense, they would have done on their own long ago — as Columbia is revising its administrative structure for the first time (The New York Times tells us) since 1810. Commissioner of Education Howe says, “Perhaps students are resorting to unorthodox means because orthodox means are unavailable to them. In any case, they are forcing open new and necessary avenues of communication.” Both Berkeley and Columbia will be wiser and better universities as a result of the student revolts. One can hardly blame the president of the Harvard Crimson for his conclusion:

All the talk in the world about the unacceptability of illegal protest, all the use of police force and all the repressive legislation will not change the fact that attention is drawn to evils in our universities in this way. As long as students have no legitimate democratic voice, attention is drawn only in this way.

The students’ demand for a “legitimate democratic voice” in the decisions that control their future is part of a larger search for control and for meaning in life. The old sources of authority — parents and professors — have lost their potency. Nor does organized religion retain much power either to impose relevant values or to advance the quest for meaning. Nominal affiliation persists, but religious belief in the traditional sense is no longer widespread in college. A Catholic girl recently said that among students she knew, “there definitely is no interest in any doctrine about the supernatural. The interest is in human values.” An eastern sophomore says: “Nobody thinks about religion but probably respect people who have religion because it is so rare.”