Uncovering Caribbean Beauty: An Interview with Our May/June 2019 Cover Artist

Shari Erickson is an American contemporary artist who spends much of her time exploring the Caribbean. “For three decades my artwork has focused on the Antilles islands, recording the beauty of the tropical landscape and the rhythm of its culture,” says Erickson, whose work Pretty in Pink appears on our May/June 2019 cover. The painter’s love of the human form and movement – infused with light and vibrant color – is at the heart of her work.

We took a minute to talk to Erickson about her gorgeous paintings.

Saturday Evening Post: Can you tell us more about what inspired you to paint the image that appears on the May/June 2019 cover of The Saturday Evening Post?

Shari Erickson: Inspiration is easy to come by in these beautiful islands. There’s an abundance of tropical landscapes, bright colors everywhere, and a lack of commercialization. The scene of the cover art is an everyday sight; just a passerby returning from the market, protecting herself from the midday sun.

Post: Do you know the woman in the piece? Can you share the details of the place, time, and elements of the painting?

Erickson: I didn’t meet the lovely lady in the piece. I try not to be an annoying tourist, being intrusive or disturbing the natural event. Essentially, I’m a studio painter working with oils on canvas. I want to record as much as I can, as fast as I can, to capture the normal moments of island life. So in my travels I rely on sketches, photos, and bullet point notes that return to my studio in the woods where I compose the elements of a memory. For instance, sometimes I might depict a chattel house from Antigua with a banana tree from St. Lucia and a child I met in St. John.

Post: Why are you inspired to paint these Caribbean scenes?

Erickson: I love these people and places that I want to record and celebrate before they are gone.

Post: Why do you say “before they are gone”? Are elements of island life disappearing?

Erickson: Of course, time and tourism take their toll in the Antilles, as with especially beautiful places everywhere. Even those unpredictable hurricanes (which seem to be getting worse) can change the landscape along with irreplaceable architecture, delicate reefs, and traditional crops. Language, art, and customs bend to the future, but, thankfully, the people always remain “Irie” — defined as “pleasingly good.”

Post: Tell us about your choice of and placement of colors.

Erickson: My use of color is totally intuitive now, born of forty years mixing and experimenting so they describe my vision by working in unison.

Post: What media do you typically work in?

Erickson: I’ve had a lot of fun with many mediums on assorted media, but for me, nothing feels or performs as well as quality oil paints.

Post: What is your favorite thing about being an artist?

Erickson: It’s an incredible gift to realize that you really do see the world differently than others. Literally, your “vision.” It takes years to understand this difference and nurture it.

Post: When did you first realize that you had a vision that was different? Have you always been an artist or is this something that you nurtured later in life?

Erickson: I always felt I had an artist inside me. As I grew up I became aware that I was literally seeing more details in things than others. In the way people might react passionately to hearing new music, I react the same to a new shape, a new color, a new way light falls through a tree that I hadn’t noticed before. Realizing all this, I studied and worked hard to become a professional artist.

Post: What advice would you give to aspiring artists?

Erickson: Find your voice and embrace it. Draw and sketch constantly which becomes the reliable foundation of better paintings. Stay loose — enjoy yourself. Fight any sneaky voices that tell you judgmental lies and discourage you. Work. Work.

Cover Collection: Yuletide Shopping Shenanigans

The commercialization of Christmas is not a modern phenomenon. Holiday shopping can be a joy, but it often veers toward comedy. In the hands of Post cover artists, the mundane experience of making lists, checking them twice, and finally scavenging neighborhood stores to gather up holiday bounty is presented as equal parts delight, misery, and just plain silliness.

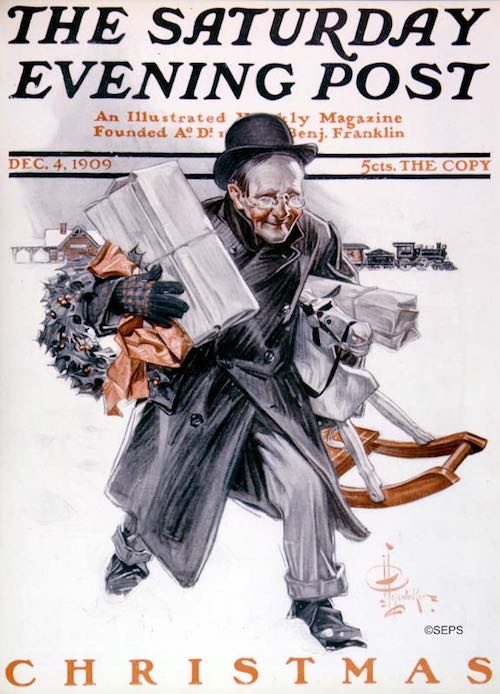

Under the humorous guise of this painting’s subject matter, Norman Rockwell makes use of snow as white space to break the image of an overloaded grandfather into completely disjointed components. It’s not quite a human being we are looking at, but pieces of one—a subtle nod to cubism, perhaps?

Incidentally, “Pops” Fredericks, the model for this illustration, was an actor who never quite succeeded on the stage or the screen, but who achieved immortality on Rockwell covers as a cello player, a seasick cruise passenger, a hobo, Ben Franklin, Santa Claus, and a beloved doctor patiently examining a little girl’s doll.

This stunning self-portrait by one of the Post’s more popular female artists makes use of winter’s white in an unexpected way. Not only is the background washed out—evoking a sense of snow—but the gifts are a stunning white against the stark black of the subject’s mink. The multi-talented McMein, a Midwestern girl from Quincy, Illinois, and star pupil of the Chicago Art Institute, moved to New York City with dreams of succeeding as an artist, poet, or musician. The year before painting this cover, she traveled to war-torn Europe as a correspondent for McClure’s Magazine. In the mid-1930s she would make an indelible stamp on the marketing world by creating the face of Betty Crocker.

December 13, 1919,

Neysa McMein

The rocking horse was not new in 1909. It had been popularized in England during the 1800s, then galloped from small workshops into factory production. By the early 20th century, it was a staple toy in America and made frequent appearances on The Saturday Evening Post’s covers, especially around Christmas. Notice the detail in the harried commuter’s overcoat and pants. Leyendecker, whose roots were in fashion advertising, always gave close attention to the clothing of his models. A mentor to Rockwell, Leyendecker was also a darling of the public. At one point his fan mail eclipsed that of legendary film actor Rudolph Valentino.

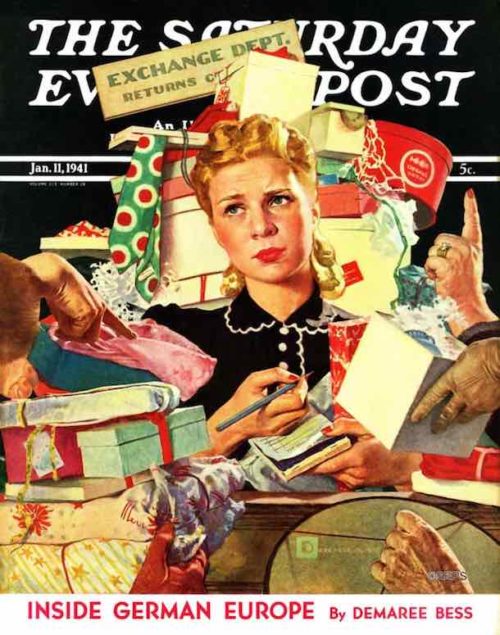

January 11, 1941,

Spencer Douglass Crockwell

The clerk’s face, almost floating in a sea of returned gifts, says all that needs to be said about the post-Christmas letdown. With its emphasis on the commonplace, the Post (and much of America) was willfully ignoring the global crisis brewing across the oceans. (The attack on Pearl Harbor that galvanized our engagement in World War II was still 11 months away.) Notice the signature, bottom right. Crockwell, who illustrated 18 covers for the Post, took to signing his illustrations “Douglass,” “DC,” or simply “D” to avoid being confused with another Post cover artist with a very similar last name.

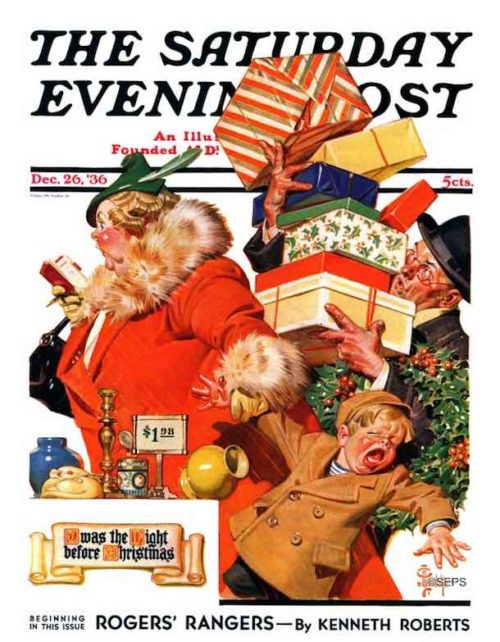

December 26, 1936, J.C. Leyendecker

Leyendecker was one of the longest running of the Post cover artists and certainly one of the most versatile. While best known for his stylish illustrations of fashionable people, he occasionally produced comic numbers, such as this colorful depiction of frantic, last-minute shopping. While many playful elements are at work, notice the visual pun of the bulky mom who bears an uncanny resemblance to St. Nick.

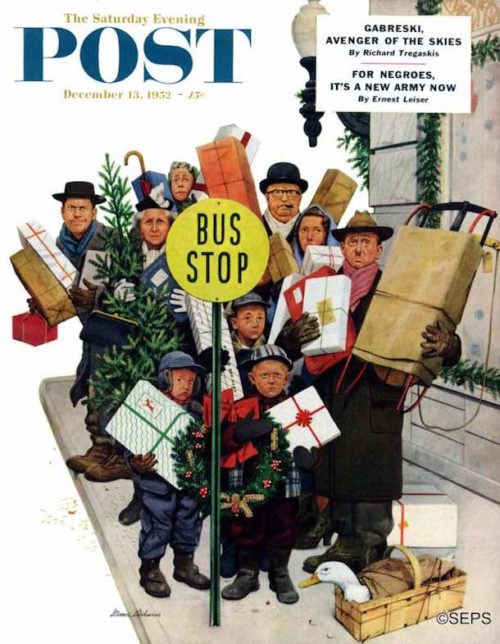

December 13, 1952, Stevan Dohanos

For this painting, Dohanos asked a man at a local nursery to

“saw me down a small Christmas tree to take out.” The little tree made this quirky cover in which all the players — duck included — seem remarkably complacent considering the circumstances. Post writer Rufus Jarman, a neighbor of Dohanos, makes a cameo appearance as the determined-looking man to the left of the tree.

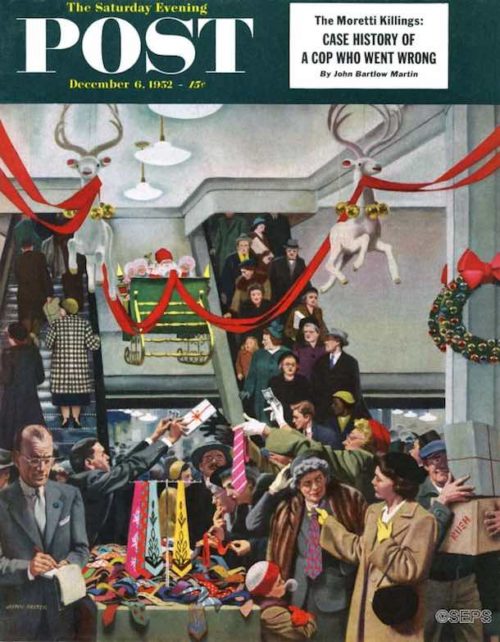

December 6, 1952, John Falter

Even 65 years ago, the ugly tie was universally recognized as the least desirable Christmas gift one could receive. But sometimes, well, that’s the best a person can do. For this hectic scene, Falter relied on his background working at his father’s clothing store in Falls City, Nebraska. By the late 1930s, Falter had moved to New York and was painting shirts and ties for Arrow Shirt ads before being discovered by the Post.

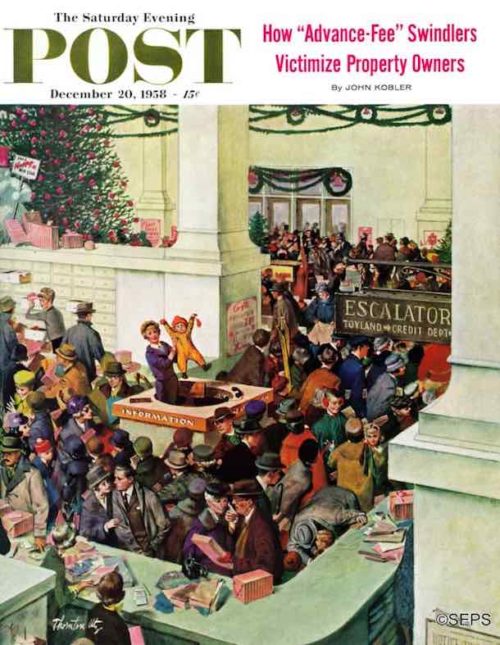

December 20, 1958, Thornton Utz

At the center of the image, a child at the Information booth will soon be reunited with misplaced parents. Meanwhile, countless other dramas are being played in Utz’s shopping pandemonium. Utz began drawing cartoons at 12 and knew he wanted to be an artist by the time he graduated from high school. But later he would say that he and a like-minded friend “could probably have been talked out of the whole idea if we’d been offered a good job driving a laundry truck.” With his knack for capturing humor in everyday situations, Utz became one of the most successful cover artists of the 1950s.

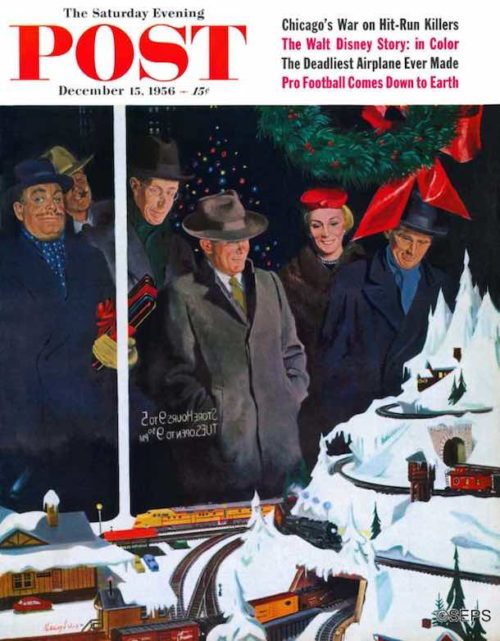

December 15, 1956, George Hughes

While drawing plans for a new home near Arlington, Vermont, Hughes decided to designate a room for his model trains. Months later, when breaking ground for his new home, his responsible side won out: He abandoned plans for the train room. But did he abandon his wish? One can almost feel the artist’s yearning for the magic of toy trains in this captivating holiday window display.

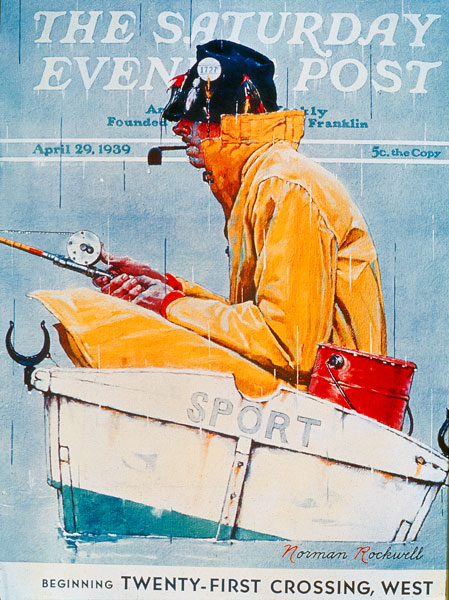

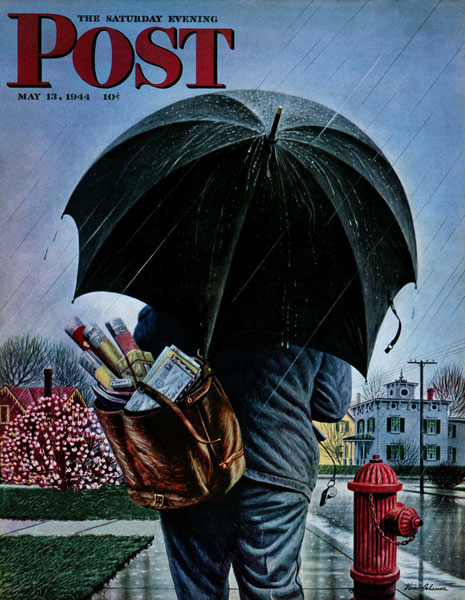

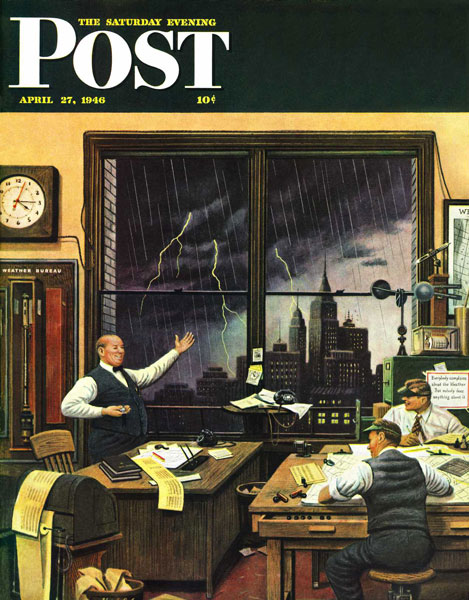

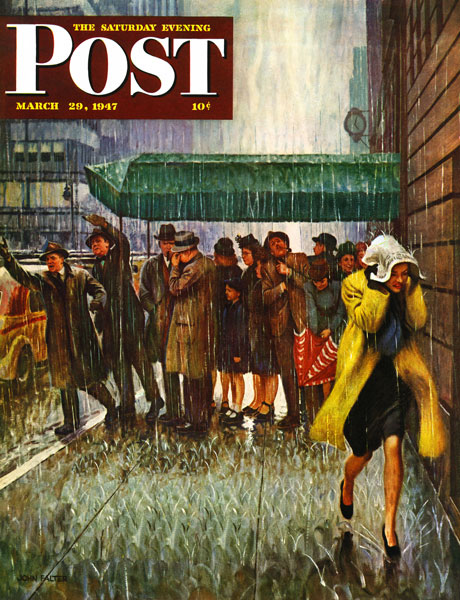

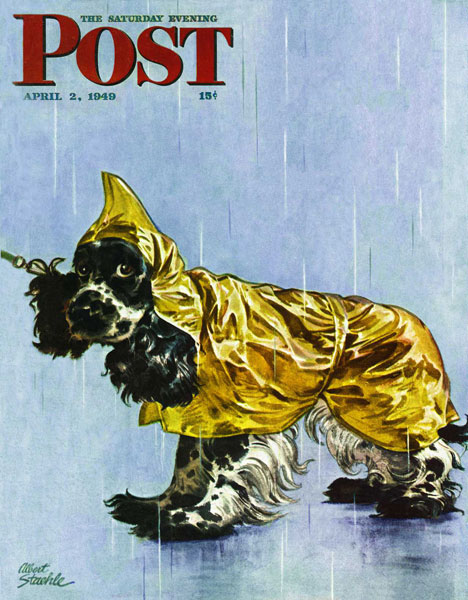

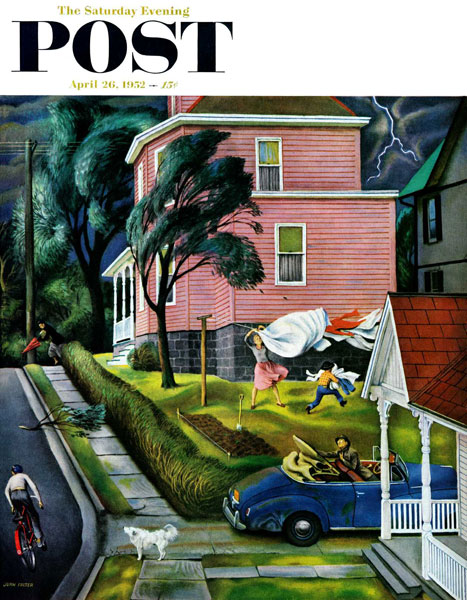

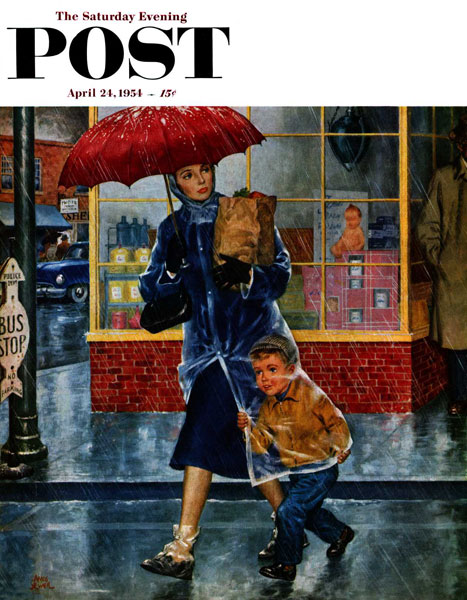

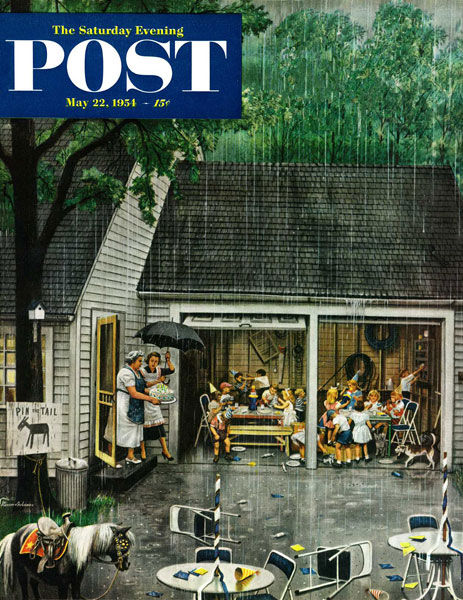

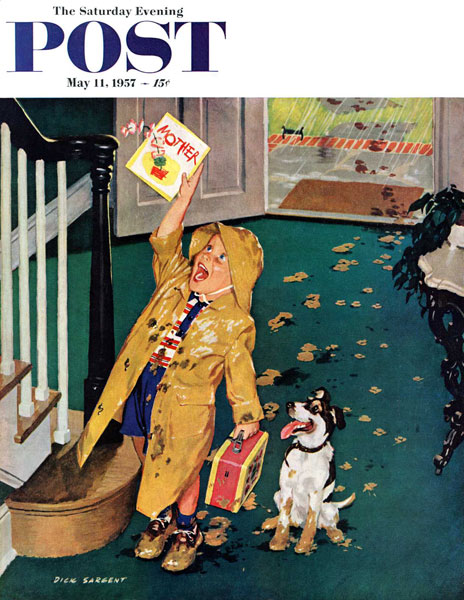

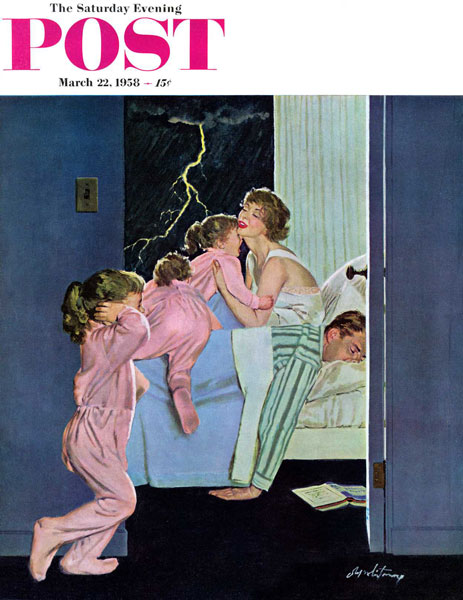

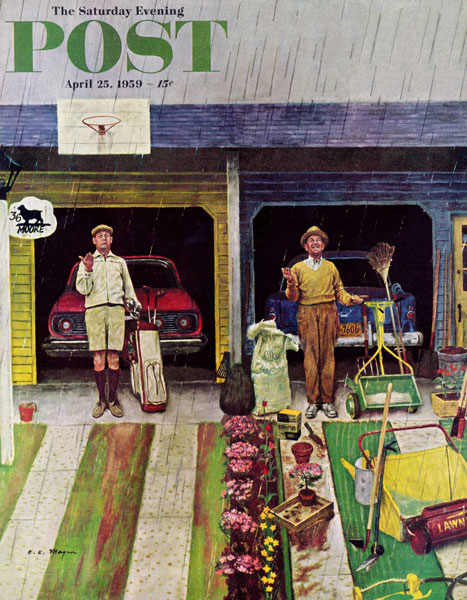

April Showers

April showers may bring May flowers, but before the flowers come there’s usually some fun to be had — or spoiled.

The way a rainy day affected American leisure activities was a regular subject for Post cover artists. The common conundrum of soggy groceries or a cancelled golf outing is something anyone can relate to. Even if your ambitions are modest — a fishing trip, some yard work, a barbecue — rain can put a damper on things. And it’s funny, but only when it’s not happening to you. Here’s a rare view of some of our classic rainy day art from our archive.

Rainy days on the covers of The Saturday Evening Post (click on the covers to see larger image):

Classic Covers: Post-Thanksgiving Shopping

Let the post-Thanksgiving shopping begin! Post cover artists over the decades have shown us how it’s done. And how darn tiring it can be.

The kid is having a meltdown; Dad already has more than he can handle, but Mom has a list and is on a mission! The 1936 cover by artist J.C. Leyendecker has a message: If you see a shopper this determined, get out of the way!

Children and husbands are not the only sufferers. Take the “Santa’s Helper” on Norman Rockwell’s 1947 cover. The poor woman in the toy department is footsore and exhausted. Rockwell did the cover in Chicago in the summer heat. Deciding the scene needed more dolls, he set about shopping, somewhat sheepishly, until he had “forty-eight dollars’ worth”. In 1947 we’re sure this amounted to a mountain of dolls. According to the editors, Rockwell thought “he probably has more dollies than any other kid of fifty-three.”

Crammed full of shoppers and travelers is the December 1944 cover of a Chicago train station also by Rockwell. Santa ringing a bell, servicemen kissing sweethearts – even some poor schmuck squeezing through the crowd with a Christmas tree – ‘tis the season for hectic!

The Lost Child Department (or lost parent department) is shown to us in artist Thornton Utz’s 1958 cover. A dizzying amount of hurly-burly is happening in what the editors dubbed “the Madding Throng Department Store”. A lady in the foreground is hitting hubby up for additional money and a lady in the background is considering some rather wild boxers for her own beloved. Alas, it is the poor lost little urchin that worries us! The editors assure us, however, the parents will show up, and “their distress will lose itself in the reunion—their sweetest Christmas present of the year.”

Love covers from The Saturday Evening Post? Peruse and purchase your favorites at saturdayeveningpostcovers.com.

Thornton Utz

December 20, 1958

J. C. Leyendecker

December 26, 1936

Norman Rockwell

December 23, 1944

Norman Rockwell

December 27, 1947

Classic Covers: By the Light …

… of the silvery moon? of a sparkling Christmas tree? of a glowing Jack-o’-lantern? The “star” in some paintings is not just the subject of the piece, but the lighting—a face lit by lamplight, a city bathed in sunshine, or the reflections of a snowfall. Post cover artists show intriguing use of light in all seasons—outdoors and some interesting, or even creepy, indoor lighting.

San Francisco is the city with the sunbathed background in the September 29, 1945, cover by artist Mead Schaeffer. Frisco was a jumping-off place during the war, and the sailors in the cover are all jumping onto a streetcar heading toward the Golden Gate Bridge. The angle of the sunlight and shadow is intriguing;

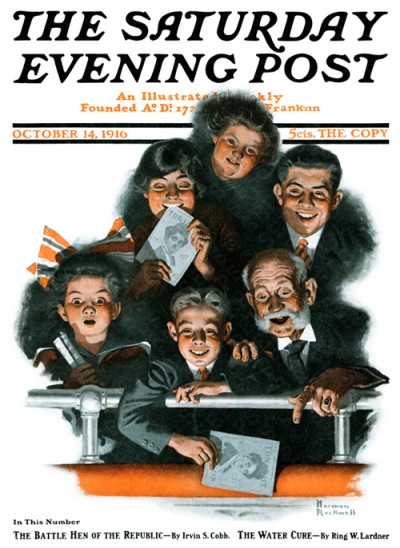

A good buddy of artist Schaeffer, a guy named Rockwell, knew a thing or two about lighting, and one of our favorite examples is from 1916. The whole family is watching a movie—notice the Chaplin programs. Rockwell, as we’ve said before, is all about faces, and their expressions are magical, enhanced by theater lighting.

One of the loveliest examples of lighting we found was the luminous glow of a Jack-o’-lantern in artist Pearl L. Hill’s November 1, 1924, cover. It’s hard to steal the scene from a pretty girl in a party dress, but the mean ol’ carved pumpkin is almost doing just that.

The light casts eerie shadows in J.C. Leyendecker’s December 1, 1934, cover. We doubt the cook in this cover planned it this way, but she couldn’t have picked scarier lighting for her spooky story. She seems like a good storyteller, but let’s hope the little boy (and cat) doesn’t have nightmares.

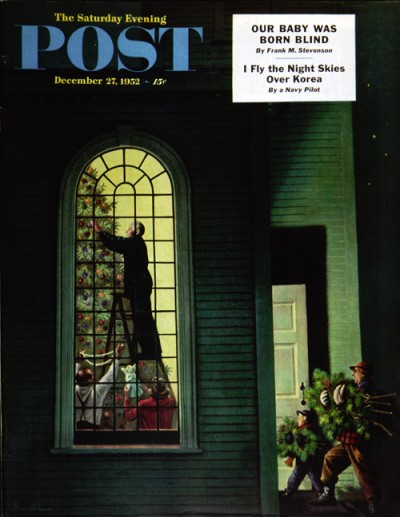

We love the way cover artist Stevan Dohanos plays with light in his holiday cover from 1952. We have a voyeuristic view into a church where the Christmas tree is being decorated, and just enough light is spilling from the door to show us the hardworking man and boy bringing in armloads of pine boughs. Love the too-tall Christmas tree, but we have to say lighting is the star of this one.

Gallery

Mead Schaeffer

September 29, 1945

Norman Rockwell

October 14, 1916

Pearl L. Hill

November 1, 1924

J. C. Leyendecker

December 1, 1934

Stevan Dohanos

December 27, 1952

Classic Covers: George Hughes, Signs of Summer

Seems like the lady of the house (or yard) can’t decide where the tree looks best. The cover from April 9, 1955, shows a weary laborer digging holes for a tree. That’s one tree and several holes. (Oh, and note the truck in the driveway.)

George Hughes (1907-1990) began his career with the Post illustrating Guy Gilpatric’s Glencannon stories and other seafaring fiction. A resident of Arlington, Vermont, he was a neighbor of such noted Post cover artists as Norman Rockwell, John Atherton, and Mead Schaeffer. Like Rockwell, Hughes believed in realist painting and insisted on working from actual settings. He spent an entire day learning how to properly place clothespins for his first Post cover of April 17, 1948, in which a mother hangs clothes as her son parades home, showing more dirt than the law should allow.

Hughes’ favorite theme was unforgettable family situations with which Post readers could readily identify. Hughes, who had five children, could easily relate to scenes such as Coming Up Roses, where another too-busy Mom notices her toddler pulling up roses. A Post favorite shows a mom taking a nice cold glass of lemonade to the hardworking boy mowing the lawn. Is this the quintessential 1950s cover or what? Shades of June Cleaver.

The Fork in the Road cover (July 7, 1956) displays another familiar Hughes theme: a humorous slant on relationships. Even on a lovely summer drive, man and wife disagree on which way to go. Adults seeking peace and quiet also appear in Hughes’ work, such as No Chance to be Alone, which portrays a couple enjoying a peaceful space at the beach—until a large, boisterous family discovers the same spot. In Sunday Visitors, Hughes captures a couple going back into the house to enjoy the Sunday paper after one group of after-church visitors leave … and another family comes up the walk. Sigh.

But what suggests summer better than the sight greeting the small bird watchers on the March 24, 1962 cover? No, not the bright red bird the guide is delighted to see, but over there, through the trees, on the other side of the water. Can it be? It is! The season’s first ice cream truck!