The commercialization of Christmas is not a modern phenomenon. Holiday shopping can be a joy, but it often veers toward comedy. In the hands of Post cover artists, the mundane experience of making lists, checking them twice, and finally scavenging neighborhood stores to gather up holiday bounty is presented as equal parts delight, misery, and just plain silliness.

Under the humorous guise of this painting’s subject matter, Norman Rockwell makes use of snow as white space to break the image of an overloaded grandfather into completely disjointed components. It’s not quite a human being we are looking at, but pieces of one—a subtle nod to cubism, perhaps?

Incidentally, “Pops” Fredericks, the model for this illustration, was an actor who never quite succeeded on the stage or the screen, but who achieved immortality on Rockwell covers as a cello player, a seasick cruise passenger, a hobo, Ben Franklin, Santa Claus, and a beloved doctor patiently examining a little girl’s doll.

This stunning self-portrait by one of the Post’s more popular female artists makes use of winter’s white in an unexpected way. Not only is the background washed out—evoking a sense of snow—but the gifts are a stunning white against the stark black of the subject’s mink. The multi-talented McMein, a Midwestern girl from Quincy, Illinois, and star pupil of the Chicago Art Institute, moved to New York City with dreams of succeeding as an artist, poet, or musician. The year before painting this cover, she traveled to war-torn Europe as a correspondent for McClure’s Magazine. In the mid-1930s she would make an indelible stamp on the marketing world by creating the face of Betty Crocker.

December 13, 1919,

Neysa McMein

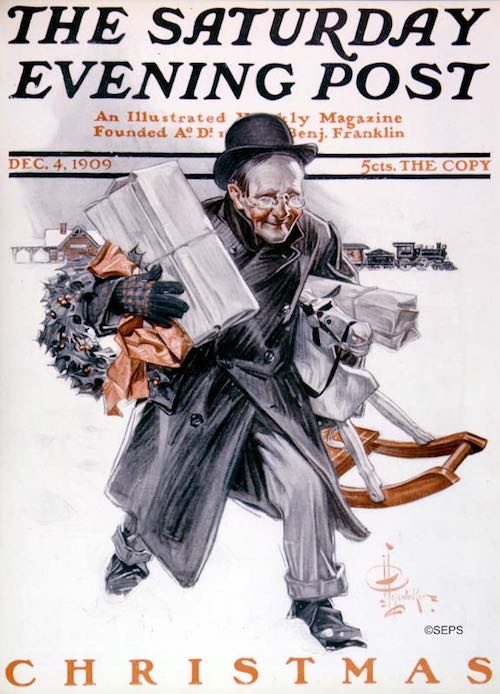

The rocking horse was not new in 1909. It had been popularized in England during the 1800s, then galloped from small workshops into factory production. By the early 20th century, it was a staple toy in America and made frequent appearances on The Saturday Evening Post’s covers, especially around Christmas. Notice the detail in the harried commuter’s overcoat and pants. Leyendecker, whose roots were in fashion advertising, always gave close attention to the clothing of his models. A mentor to Rockwell, Leyendecker was also a darling of the public. At one point his fan mail eclipsed that of legendary film actor Rudolph Valentino.

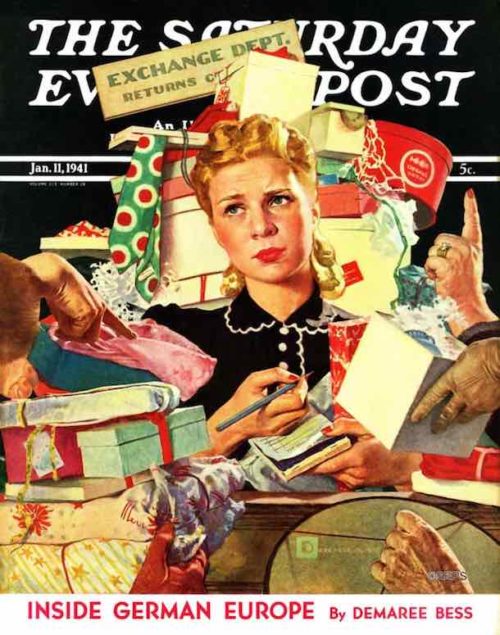

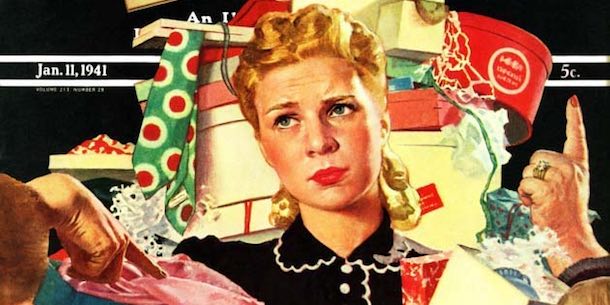

January 11, 1941,

Spencer Douglass Crockwell

The clerk’s face, almost floating in a sea of returned gifts, says all that needs to be said about the post-Christmas letdown. With its emphasis on the commonplace, the Post (and much of America) was willfully ignoring the global crisis brewing across the oceans. (The attack on Pearl Harbor that galvanized our engagement in World War II was still 11 months away.) Notice the signature, bottom right. Crockwell, who illustrated 18 covers for the Post, took to signing his illustrations “Douglass,” “DC,” or simply “D” to avoid being confused with another Post cover artist with a very similar last name.

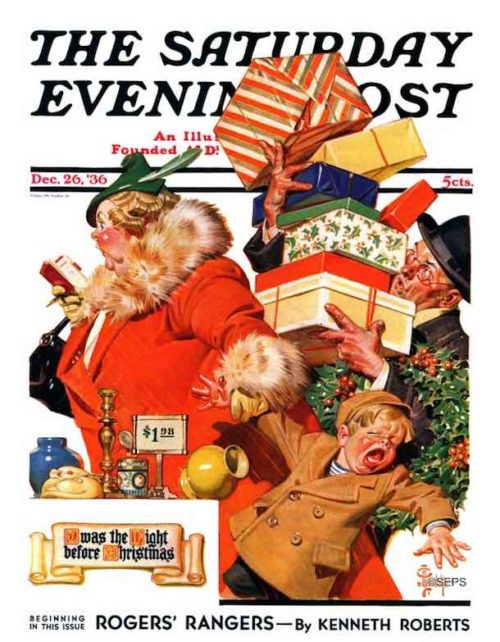

December 26, 1936, J.C. Leyendecker

Leyendecker was one of the longest running of the Post cover artists and certainly one of the most versatile. While best known for his stylish illustrations of fashionable people, he occasionally produced comic numbers, such as this colorful depiction of frantic, last-minute shopping. While many playful elements are at work, notice the visual pun of the bulky mom who bears an uncanny resemblance to St. Nick.

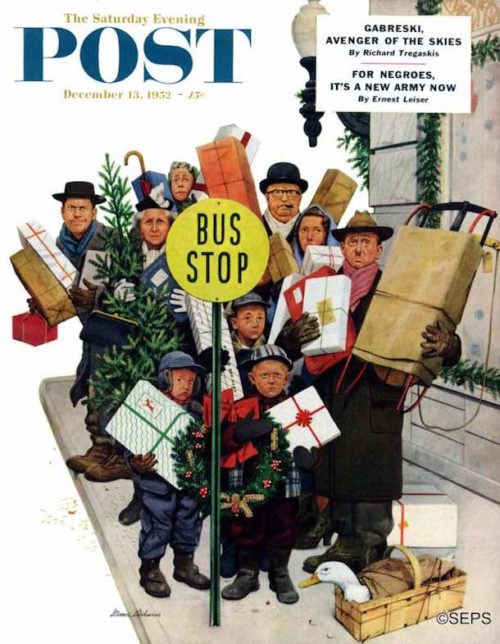

December 13, 1952, Stevan Dohanos

For this painting, Dohanos asked a man at a local nursery to

“saw me down a small Christmas tree to take out.” The little tree made this quirky cover in which all the players — duck included — seem remarkably complacent considering the circumstances. Post writer Rufus Jarman, a neighbor of Dohanos, makes a cameo appearance as the determined-looking man to the left of the tree.

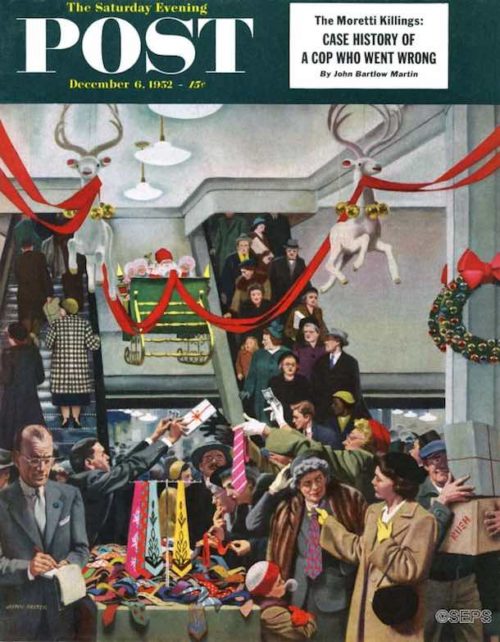

December 6, 1952, John Falter

Even 65 years ago, the ugly tie was universally recognized as the least desirable Christmas gift one could receive. But sometimes, well, that’s the best a person can do. For this hectic scene, Falter relied on his background working at his father’s clothing store in Falls City, Nebraska. By the late 1930s, Falter had moved to New York and was painting shirts and ties for Arrow Shirt ads before being discovered by the Post.

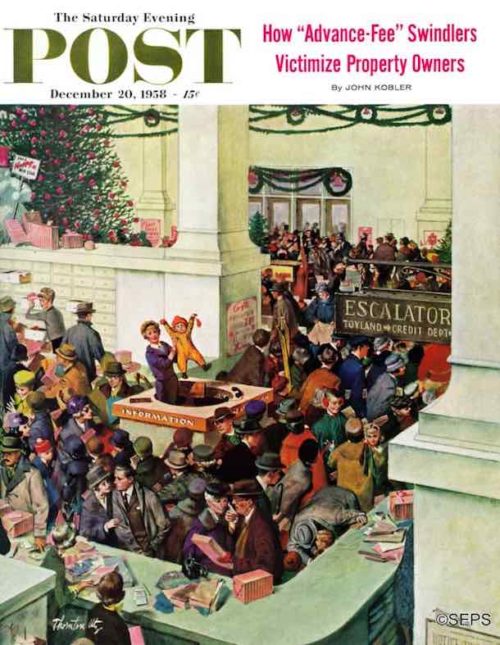

December 20, 1958, Thornton Utz

At the center of the image, a child at the Information booth will soon be reunited with misplaced parents. Meanwhile, countless other dramas are being played in Utz’s shopping pandemonium. Utz began drawing cartoons at 12 and knew he wanted to be an artist by the time he graduated from high school. But later he would say that he and a like-minded friend “could probably have been talked out of the whole idea if we’d been offered a good job driving a laundry truck.” With his knack for capturing humor in everyday situations, Utz became one of the most successful cover artists of the 1950s.

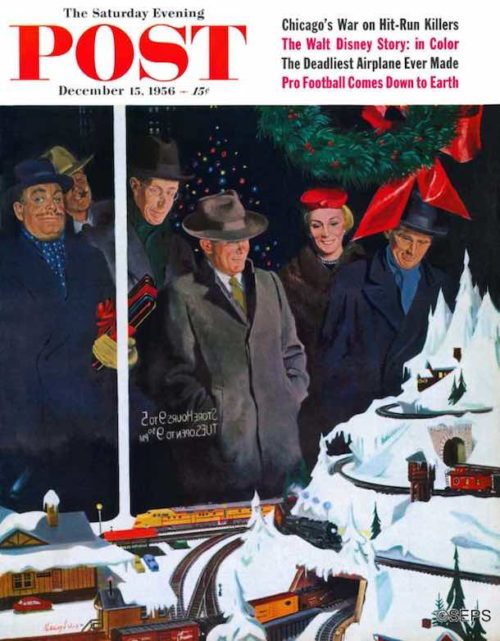

December 15, 1956, George Hughes

While drawing plans for a new home near Arlington, Vermont, Hughes decided to designate a room for his model trains. Months later, when breaking ground for his new home, his responsible side won out: He abandoned plans for the train room. But did he abandon his wish? One can almost feel the artist’s yearning for the magic of toy trains in this captivating holiday window display.

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

The 1919 cover at the top is very striking for all the reasons you mention. She’s VERY beautiful; no wonder she drew a self-portrait. It would have been a crime not to. Very accomplished woman I’d like to know more about.

I hope the kids in Leyendecker’s 1909 cover appreciate the great effort Dad’s making here. It’s unlikely he would have played the guilt card back then. Ask me if I would.

This poor young woman in Crockwell’s post-Christmas cover needs a little helper—-in more ways than one!

Leyendecker’s ’36 cover is brilliantly painted, but is depicting nothing short of a disaster in progress here—–terrible all around; my God.

The next 3 are great, but the one at the bottom by George Hughes has one hell of a cool Christmas train set I’d LOVE to own. I’ve never seen one like this before, and I don’t think the admiring people on this cover have either.